David Gessner's Blog, page 13

October 24, 2015

October 21, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Make Your Own Work

Vasilios and crew, Sixty Shades of Cray

Last November, I directed a movie from a script I had written.

I wrote the damn thing- a comedic short meant to send up trashy literature- two years ago, then was at a loss for how to produce it. The actor I wrote it for moved across the country. I shelved it to focus on my own acting endeavors. After appearing in dozens of indies, industrials, and commercials, I wrote and acted in another short and learned a bit about bringing people together. Continued to act, but the work dried up. Grew despondent and looked for a way to kick the millstone feelings. Started listening to a podcast featuring an array of names from the entertainment industry. They all said the same thing: “make your own work.” A local actor doing just that inspired me and I was resolved. And who would direct? “I’ll direct it,” I declared, surprising myself most of all.

On a suggestion from a writer-director I respect, I asked a talented cinematographer I’d once worked with if she was game to come play. She agreed, and her enthusiasm buoyed me. She suggested a gaffer she’d like to work with, someone I knew personally and really liked. The gaffer agreed. My sound wizard friend agreed to jump on, bringing along his longtime collaborator. One of my best friends lent her support as a producer. Two more of my friends opened up their home for us to shoot in, and we gratefully and energetically annexed it.

Then came the casting…

I’ll say only this: in the end, the actors that arrived on set were exactly the ones we were meant to have, and the result was wonderful.

On this set, patience, industriousness, creativity, supportiveness, and good humor reigned. The director shuffled about on two canes: one fashioned by the experience of his cast and crew, the other by their talent. And leaning on those two canes, he learned and learned and learned from those he was directing. More often than not, the images glowing on the monitor greatly surpassed his preexisting notions of what the movie would and should be. And he gleefully realized this didn’t concern him, but thrilled him. “This is why I write movies,” he concluded, perhaps much too late. “So they can be made.”

There was a lot more to be done, of course, but I have to take the time to acknowledge the shoot’s profound effect on me.

The two days of shooting were too much of a whirlwind to allow me to make a speech or thank anyone properly when we wrapped. So I’ll just say here what I’ve come to realize. A comedic video for the internet though it is, this project is my art. Without my art, no matter its present level, I don’t consider myself to be much of anything. So I owe to this wonderful team much more than gratitude. I owe to them a piece, perhaps the most important piece, of myself. Without you guys, Kat, Paul, Georgia, Steve, Kisha, Beth, Bryce, Alex, Charles, Jamie, Alex, Jaime, Amanda, Skippy, George, Dave, Rob, James, Bobby, Sarah, And Cameron, I wouldn’t … be.

And after nearly a year of post-production, here it is. For the sake of those who worked so hard on it, view, vote “Funny,” and share.

October 13, 2015

October 10, 2015

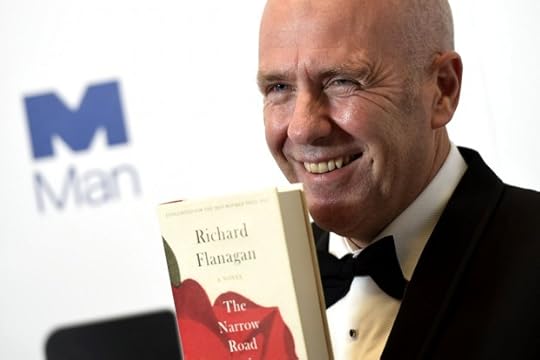

Lundgren’s Lounge: “The Narrow Road,” by Richard Flanagan

I have been a fan of Tasmanian writer Richard Flanagan ever since reading Gould’s Book of Fish (Stuart Gersen’s all-time favorite novel). Flanagan’s work might at first seem preoccupied with man’s abject cruelty to his fellows, as many of the stories take place in wretched prison settings. But if one looks more closely, there is a discernible thread weaving itself through through each narrative, examining the nature and limitations of human love and man’s capacity to endure the most dire circumstances.

Here is a passage from Flanagan’s relatively unnoticed and unremarked upon novel from 2006, The Unknown Terrorist, that captures the power of his writing:

“… The innocent heart of Jesus could never have enough of human love. He demanded it… with hardness, with madness, and had to invent hell as punishment for those who withheld their love from him. In the end he created a god who was ‘wholly love‘ in order to excuse the hopelessness and failure of human love. Jesus, who wanted love to such an extent, was clearly a madman, and had no choice when confronted with the failure of love but to seek his own death. In his understanding that love was not enough, in his acceptance of the necessity of the sacrifice of his own life to enable the future of those around him, Jesus is history’s first, but not last, example of a suicide bomber.”

Flanagan’s most recent novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North has been universally acclaimed as a masterpiece. Winner of the Man Booker Prize, The Narrow Road tells of the life of Dorrigo Evans. The interwoven strands of that history include his experiences as the leader of a group of Australian prisoners in a brutal Japanese POW camp, his intense affair with his uncle’s wife before the war and his life after the war as a surgeon and a husband and father, who becomes, to his own bemusement, rather famous mostly it seems, for being famous.

Dorrigo meets his uncle’s wife by chance in a bookstore, only learning later of their family connection and embarking upon a passionate affair that seems inevitable and that remains alive in his memory even years after it has ended. The lovers are first separated by war, but in the war’s aftermath they seem paralyzed from resuming their affair by a curious ambivalence and perhaps suspicion of what they had once shared. In its stead Dorrigo becomes a compulsive philanderer, even as he marries and becomes a father.

But at the heart of this luminous novel is the day to day life of the prison. The Japanese are attempting to build a railroad, both as military strategy and to glorify the Emperor. As a colonel, Dorrigo is in charge of the prisoners, and in his attempts to minimize the horrific toll that the combination of lack of food and hygiene and the debilitating physical labor exacts upon his men, he discovers to his surprise that he has a natural aptitude for leadership. Flanagan’s father was a prisoner in the Burma death camp and in interviews the author has spoken of how his father’s stories from the camp had impacted his own life. The unceasing misery of the camp is leavened by the prisoners’ sense of humor and resiliency, but there are passages that are difficult to read, describing as they do man’s astonishing capacity to inflict pain upon their fellows. It is the power and eloquence of Flanagan’s writing that makes this novel important and necessary and a fitting testament to the author’s father, who died on the day that it was finished.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

October 7, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Celebrate! (Or How I Won the U.S. Open)

I’ve always been jealous of the way tennis players act when they win tournaments. The way they hurl their racquets in the air, drop to their knees, lift their arms to sky, lie on their backs. The way they exult in a manner that you rarely see in other professions.

I’ve always been jealous of the way tennis players act when they win tournaments. The way they hurl their racquets in the air, drop to their knees, lift their arms to sky, lie on their backs. The way they exult in a manner that you rarely see in other professions.

Writing, for instance.

It’s been my experience that almost every writing triumph, no matter how large or small, comes with some qualification. Trained to deal with rejection, we are wary of jubilation. We know that after the rise will come the fall. We temper triumphs with the word “But” followed by some discounting phrases. Our inner Bill Belichicks squash whatever celebration we hoped for.

But this August, watching the U.S. Open and witnessing players in the throes of joyous celebration, I decided I wanted some of it. I vowed that the next time something good happened I wouldn’t immediately reach for my qualifiers but would do a little reveling instead.

As it turned out, I didn’t have to wait long. Any writer who has been around for a while can cite instances of bad timing when it comes to selling their work, but this August I had the rare experience of good timing. My agent was getting ready to go out with a proposal for my book on Ultimate Frisbee, part memoir and part history, when the International Olympic Committee officially recognized Ultimate as a potential Olympic sport, spurring articles in the New York Times and the New Yorker.

There was still a chance the book wouldn’t fly of course. This was Ultimate after all. But on the day I was scheduled to find out, one way or another, what would happen with the book, I decided to throw my old tennis racquet in the car. I was taking my yellow lab for a walk in the woods when I heard from my agent, Peter Steinberg. The news was that I had an offer on the book from Riverhead, a press I loved. I gave a few fist pumps and yelled the word “yes” a bunch of times. But I held off on any real celebration until I got back to the car. There I took out the tennis racquet and walked back over to a grassy spot near the entrance to the woods.

I did what I said I would do. I went to my knees (somewhat gingerly in old-man fashion) and threw my hands over my head. I threw the racquet in the air and then let out a yell. I lay back on the grass. Missy looked on, confused, then came over and licked my face.

It’s true there were not thousands of people up in the stands cheering me on. But you know what? It also felt good. Fuck it. A win is a win. We writers got to take it where we can get it.

October 1, 2015

Save the Shack!

We all have a place where our writing comes from and we should do all we can to protect that place. Alas, I left home at 5 am yesterday without even putting up the plywood window protector on the windows of my writing shack. It was muggy in North Carolina but the first I heard about a hurricane was when I landed in Montana (71 and dry). Now, if I understand it correctly, Joaquin Phoenix is taking aim at the shack. Here are some pictures from earlier this week BEFORE a new storm was thrown into the mix. With the rains and super moon there was already 2 feet of water inside. Not sure if it will be there when I get back Monday….

Watch out for Hadley’s old stuffed snake!

September 28, 2015

Anxious Bode Tries Out at the Comedy Cellar

Thierry Kauffmann, aka Anxious Bode

Hi, I’m Anxious. I want to thank Bill and Dave’s Comedy Grotto for inviting me to try out for the Comedy hour. But let’s get right to it! I love flying. I do. Getting on the plane can be tricky with Parkinson’s, but once I’m seated, I’m good. Now I’m supposed to make jokes about airplanes and flying and how horrible the food is. Actually the food is pretty good, especially the stuff that doesn’t land on the floor. Have you ever seen the floor of an airplane? Amazing what you find. I was looking for my dessert. Still wrapped in its aluminum foil. I started leaning back at around 4:45pm. At 5pm I was so low I could actually reach the dessert. My neighbor was down too. He had lost his smartphone. So we were both down. He looked panicked. In a cheerful way. He was an actor. Expecting calls. I thought I would help him.

I was on my way to NY. I thought, this man needs help. I could picture his life, but only if I put it inside an activity accelerator. Like those particle accelerators. At my speed, there was no way he would have worried about missing calls. I couldn’t answer the phone in fewer than ten minutes. So there I was, body in plane, mind with Mozart, trying to change course, like in slow motion. I thought if we keep up that speed, we’re going to land. “Is this your phone? I said, I saw it fall.” “Ooh, thank you so much, OMG I had not backed-up my phone since yesterday!” And followed by a torrent of normal speed words that made me wish I could speak at even that speed. But I smiled instead, slowly, then I started talking. These people, he and his friends, all actors, all stressed, in a cheerful way. I felt at home on that plane, me with no dessert yet, he with no-phone turned my-phone-is-back, so I was trying not to say something incredibly profound like it’s good to be back! But I said it anyway, protected by the code of NYC life that seems to say everything goes, everything works–you can be crazy as long as it’s for the benefit of others, and in that moment I felt lighter. The dessert when I found it tasted like happiness , it tasted like love, for this is what love does, it makes you forget the taste of airplane food. You can’t remember the taste of poached pears or that you cannot walk. When we landed I was waiting for the wheelchair from the airline. I asked to wait again–for my pill. Then, forgetting, I got up and walked. People looked at me like “We thought you could not walk.” And I felt like telling them “I was joking. It’s all a joke.”

I was on my way to NY. I thought, this man needs help. I could picture his life, but only if I put it inside an activity accelerator. Like those particle accelerators. At my speed, there was no way he would have worried about missing calls. I couldn’t answer the phone in fewer than ten minutes. So there I was, body in plane, mind with Mozart, trying to change course, like in slow motion. I thought if we keep up that speed, we’re going to land. “Is this your phone? I said, I saw it fall.” “Ooh, thank you so much, OMG I had not backed-up my phone since yesterday!” And followed by a torrent of normal speed words that made me wish I could speak at even that speed. But I smiled instead, slowly, then I started talking. These people, he and his friends, all actors, all stressed, in a cheerful way. I felt at home on that plane, me with no dessert yet, he with no-phone turned my-phone-is-back, so I was trying not to say something incredibly profound like it’s good to be back! But I said it anyway, protected by the code of NYC life that seems to say everything goes, everything works–you can be crazy as long as it’s for the benefit of others, and in that moment I felt lighter. The dessert when I found it tasted like happiness , it tasted like love, for this is what love does, it makes you forget the taste of airplane food. You can’t remember the taste of poached pears or that you cannot walk. When we landed I was waiting for the wheelchair from the airline. I asked to wait again–for my pill. Then, forgetting, I got up and walked. People looked at me like “We thought you could not walk.” And I felt like telling them “I was joking. It’s all a joke.”

[Anxious Bode is Thierry Kauffmann, who lives in Grenoble, France, where he’d do stand up if he could stand up, and fights Parkinson’s, all while keeping his chops on the piano.]

September 25, 2015

OBITS

We are lucky to have this beautiful essay on facing death by my former student and current friend, Tara Thompson.

We are lucky to have this beautiful essay on facing death by my former student and current friend, Tara Thompson.

OBITS

“Sometimes you wake up. Sometimes the fall kills you. And sometimes, when you fall, you fly.”

—Neil Gaiman, The Sandman, Vol. 6: Fables and Reflections

The doctor shows it to me on my CT scan as I prop myself up in the bendy, mechanical hospital bed where I’ve spent several consecutive, restless nights with an IV trickling into my veins. You see, here, he points to the computer screen, that’s fluid, which isn’t good, and this is where most of the damage is, scar tissue in your upper lobes. (I’ve been told already by other doctors that this recent lung disease is probably from the chemo and radiation I had years ago for my former disease: leukemia. How many diseases must one person have?) The pneumonia is colonizing here, he says.

Colonizing? I think that was the word he used. With the IV Dilaudid, Phenergan, and antibiotics coursing through my body, I visualize a colorful map of the thirteen original colonies and images of Pilgrims and Indians fighting each other. These lungs I am viewing stand alone on a textbook page or pixilate on a computer screen. They are not the ones inside my body.

The day after I return home from my four-day hospital stay, hung over from all the medication, I tell my sister, Whitney, on the phone that I haven’t left a mark on the world, and who knows, I could be gone soon, what with this pulmonary illness that has infiltrated my lungs, leaving lacy patterns in the upper lobes like doilies floating among debris.

But I haven’t done anything, I say to Whitney, I haven’t made a difference at all. I can’t even leave any kids behind. No husband. Nothing! I moan, out of breath. Neither of us likes moaners or whiners or complainers, and even as I hear myself saying the words, I hate myself for doing so. I don’t want to be this person. It wasn’t supposed to turn out like this.

My cat, Webster, whirls like dust around my ankles. I barely see him but know he’s there. He needs a new home. Soon. Due to this lung stuff and the fibrosis. Now, there’s another word to Google. Fibrosis. And interstitial lung disease. Two things to Google.

Whitney asks me if I read the obituaries. No, I say, do you?

Yes, she reads them every day in an actual newspaper that arrives on her concrete driveway in a cul-de-sac in a family-filled Mississippi neighborhood, many miles away from my North Carolina townhouse.

Most people live average lives, she informs me. Most people don’t leave a big splash on the world but just live quiet, normal lives. Who’s to say what a great life is?

The next day she texts me: In today’s obits we have a retired seamstress and a retired homemaker who enjoyed gardening, painting, and crafts. See what I’m saying?

No one wants my cat despite his glossy black coat, clear green eyes, and flawless health record. At age ten, he is too much of a risk. What should I tell him? Age discrimination is a bitch.

#

When I’m in a quiet room or lying in my bathtub after the water has stopped running, I hear a subtle flutter in my lungs. A hummingbird’s whir. It’s not alarming on its own, but it’s scary in my life’s context: two bone marrow transplants to fight leukemia in my mid-twenties, including full body radiation, loads of chemo, and harsh drugs. It’s twenty years later; I don’t think I was supposed to make it this long. Survival has its consequences.

Text from Whitney: Obit for the day: 64-year-old retired intensive care nurse…enjoyed reading, traveling, and caring for her pets.

#

I must undergo an echocardiogram at Duke Medical Center because my new pulmonary specialist is concerned that in addition to my lungs, my heart, too, may be compromised from the treatments that kept me alive so many years ago. The bright-eyed female technician decides to use me as an example to illustrate specifics about the echo machine to another young woman, a resident doctor. You don’t mind, do you? the resident asks. I don’t; I am a great specimen. It’s a skill you acquire over time.

The technician pushes the device (a transducer) around my chest, which is spread with slick gel. She and the resident study the screen along with me, although I have no idea what I’m looking at. It’s an amorphous blob with an area that looks like a small mouth opening and closing. So, you have pulmonary disease as a result of the bone marrow transplants? the technician asks, making small talk as she tries to nudge the device under my ribs. You never smoked or anything? I stare at her bouncy chestnut hair and shiny barrettes. Right, I say. All that chemo and radiation.

It’s like what we always say. The resident pipes in, confident in her seniority despite her youth. You just trade one disease for another.

#

A couple years ago, I learned on Facebook that a childhood friend, a veterinarian, had committed suicide. I knew her in elementary school, before my family moved away to a different town. She remains permanently young to me, a sliver of life in a faded snapshot, standing beside me, elbows touching mine as I blew out the candles on my birthday cake. She had traveled to Africa to save goats and pigs and horses; Rwanda to work on AIDS prevention; Pakistan, to field-research diseased donkeys. There are photos and articles published in journals about her lust for life and goodness of heart. A very long obituary.

She ended it at age forty-four with medication she gave the animals to put them to sleep, the ones beyond repair. She will never grow old, corrode, slump over with brittle bones. She will never wheeze on a lung machine or need an oxygen tank to breathe. After they cremated her, a friend posted an image online of the clear plastic bag containing her ashes, alongside photos from her life and an invitation to the Nevada desert location where the ceremony would take place. There was her existence, leaping from my computer screen: a youthful woman with vibrant colors juxtaposed with a dull bag of ashes to be scattered.

#

The pulmonary doctor at Duke e-mails the results of my echocardiogram: The heart seems to pump well and there is not any scarring of the heart sack (which can occur sometimes after radiation or chemotherapy) …good news. Ha! What does he know about my heart’s scars, which I can assure you are too numerous to count?

I recall my early twenties—prior to the leukemia—when I pursued an acting career. I posed for several photographers for headshots and publicity-type photos. One of the photographers I worked with had been in a fire as a child. His face was patched with varying shades of skin, like a quilt—skin lifted from different parts of his body and grafted onto his face. Some of it looked hardened and callused, and the overall effect was distorted. I tried not to stare as I thought about how difficult it must be for him to live with all those scars on the outside.

#

My sister comes to the rescue. She will take Webster. We will fly him to Mississippi where he will join her robust family: four cats, two dogs and two kids, in addition to Whitney and her husband. They will protect him and his clawless front paws, which make him slightly vulnerable. It will be a big adjustment for him, as he is a bit of a loner. But we creatures adapt to survive, do we not?

This is not the first time my sister has saved me. Her bone marrow was a perfect match for me when I was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and needed a transplant. When I had a recurrence two years later and needed a second transplant, she saved me again. Her marrow kept me from dying years ago, and even now, a mutated version of it courses through my body, through my bones, keeping me alive.

I find myself reading online obits lately, and this one jumps out at me: Age eleven, an avid rock collector, also enjoyed building with Legos… An amazing big brother to his little sister… I hear my sister’s voice: Who is to say what a great life is?

There are times when I feel that I cannot take another blood test, ER visit, needle under my skin. Cannot swallow another purple, pink, yellow, white pill. I study the side effects printed on the info sheets enclosed with one of my most recent drugs (yet another drug to combat this lung issue), and I examine the long-term consequences of taking it. I search online for more information. WebMD and other medical sites paint a dismal picture: Potential for tumors after taking drug over an extended period of time. Potential for other types of cancers.

But I’m banking on the present, not necessarily the future. In a way, the resident doctor at Duke was right about trading one thing for another. If I have to choose, I’ll take the present.

Whitney texts me photos of Webster gazing up at the camera phone, his green eyes sparkling from the flash. He can’t play outside with the other cats but he has found a private spot inside a large closet with a window in the master bathroom. He perches on the wide window sill and watches kids cavorting in the cul-de-sac, birds perching on tree limbs. Perhaps he sees a cat scoot by from time to time. My sister has informed me that despite their attempts to coax him out into the rest of the house, Webster seems happiest in his little space. He tiptoes out of the closet to be pet and held by the family when they are nearby, and he sometimes ventures into the adjacent master bedroom at night, stalking around the room in the dark and returning to the closet before dawn. I wonder what the shock of the sudden change in his life has done to him. Adjustments can take a long time.

I lounge on a sofa in a friend’s living room, watching Game of Thrones. It’s season four, episode eight: Robin, a sickly boy who has been sheltered and overprotected in a castle his whole life has recently been given the powerful position of “Lord” after his mother’s death.

Robin is terrified of going out into the world, where so many dangerous things lurk, where he could die. Baelish, his stepdad, tries to calm him down, telling him that people often die from everyday causes (“People die at their dinner tables. They die in their beds… Everybody dies sooner or later…”) and that instead of fearing his inevitable death, he should spend time focusing on his life, which lies before him. “Take charge of your life for as long as it lasts,” Baelish tells the boy.

I get a chill as I watch; Baelish is speaking directly to me. It’s a shift in mindset: don’t focus on dying, focus on living.

The more damaged your lungs are, the prettier they look on the screen—at least that’s what I’ve concluded so far, based on my observations of X-rays and CT scans. Like butterfly wings filled with flecks and intensity. A doctor once informed me that she knew of a case in which a person had one lung removed, and years later, the remaining lung began regenerating a new one in the vacant space, much to everyone’s surprise. I’ve thought about that a lot lately, and instead of an ugly spongy lung, I find myself envisioning a bright yellow sunflower growing slowly into the void. Brightening the darkness.

Back home, I jot a note on a scrap of paper and place it on my nightstand: Focus on how you will live.

This essay originally appeared in:

Prick of the Spindle: A journal of the literary arts

Volume 8.3

Publication date: 9/23/14

September 21, 2015

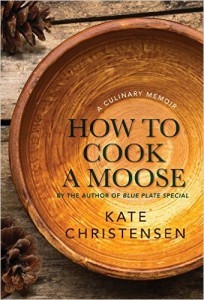

Lundgren’s Lounge: “How to Cook a Moose,” by Kate Christensen

Early in her career author Kate Christensen consistently published some of the smartest, cleverest and most entertaining works in contemporary fiction (The Astral, The Epicure’s Lament and The Great Man. among others). Then she turned her extraordinary talents to memoir with Blue Plate Special; An Autobiography of My Appetites. Now she offers a love affair to her newly adopted home of Maine and the unique culinary culture flourishing there, in How to Cook a Moose: A Culinary Memoir (Islandport Press).

Escaping from the environs of New York City, Christensen migrates northward with her new love, a fellow writer. They decamp to his family’s homestead, a rustic New Hampshire farm perched on the shoulder of the White Mountains. Eventually their wanderings lead them to Portland, a small city poised on the precipice of a cultural and gastronomical explosion. The small ‘city by the sea’ becomes a targeted destination for the newly minted foodie tourism business and trendy eateries sprout like mushrooms from Portland and on up the coast (or ‘downeast,’ as the natives describe it).

Christensen lovingly recounts intimate and exquisite dining experiences, while also giving attention to the crucial role played by a farming and fishing and gathering culture and community that sustains the ‘local’ philosophy of the foodie scene. But while reading an account of one deliriously presented meal after another, it becomes difficult to ignore the elephant in the room: this is food for the privileged–it is a celebration of the art of the meal, but it is also often offered in settings far beyond the means of many people.

As a former farmer, my favorite episodes from this enchanting memoir are those when the author detours from the well-trod path to the latest restaurant of the week and sojourns downeast to dine with friends who harvest lobster and grow much of their own food, or  when she visits the family farm of her good friend Melissa (another wonderfully talented writer), whose father happens to be Eliot Coleman, one of the gurus of the sustainable farming movement. For as my friend John was always fond of asking, as we sat down to eat at his Wisconsin farm, table arrayed with a freshly butchered chicken roasted to perfection, produce harvested minutes before, fresh goat milk and butter from Bessie outside the kitchen door: “I wonder what the Queen of England is dining on tonight?” And ultimately that is what this rhapsodic memoir is about: celebrating good, fresh food, prepared with love–while the issue of how sustainable it all is inevitably weaves its way into the narrative, the real message is, let’s simply appreciate it while we can.

when she visits the family farm of her good friend Melissa (another wonderfully talented writer), whose father happens to be Eliot Coleman, one of the gurus of the sustainable farming movement. For as my friend John was always fond of asking, as we sat down to eat at his Wisconsin farm, table arrayed with a freshly butchered chicken roasted to perfection, produce harvested minutes before, fresh goat milk and butter from Bessie outside the kitchen door: “I wonder what the Queen of England is dining on tonight?” And ultimately that is what this rhapsodic memoir is about: celebrating good, fresh food, prepared with love–while the issue of how sustainable it all is inevitably weaves its way into the narrative, the real message is, let’s simply appreciate it while we can.

Kate Christensen will be reading from How To Cook a Moose: A Culinary Memoir on Tuesday, Sept 22nd at 5:00 at Sonny’s Bar and Restaurant in downtown Portland (83 Exchange St.) The event is co-hosted by Longfellow Books and Islandport Press. It promises to be one of the literary events of the summer season.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

September 15, 2015

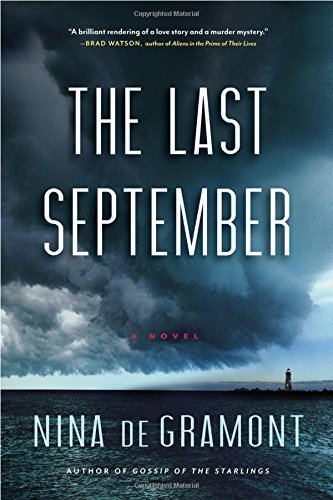

Table for Two: An Interview with Nina de Gramont on Publication Day

Bill and Dave’s doesn’t always pay for a private jet to Cape Cod for lobster rolls at the Sesuit Harbor Café, nor for 12 professional parachutists to fly our subject safely down to Earth and our dinner conversation, but Nina de Gramont is one of our favorite writers and people and also married to Dave, so. It’s sunset, it’s summer still, this golden clear month of September, and this is familiar territory for Nina, this storied Cape Cod, but also in part the setting for her new novel, The Last September, about a woman whose greatest love is shattered by a murder that takes place in the first pages, even as the story moves back to the days before all that. But our meal has arrived, and the sun is a red ball on the horizon, and today is publication day.

Bill: Congratulations, Nina, on a great new book. I enjoyed it immensely, and couldn’t put it down, also really enjoyed re-reading passages. It’s beautifully put together, vivid, harrowing, smart, and even in the roughest moments, delicate, musical, compassionate, fine. Your protagonist, Brett Mercier, is named for the Hemingway character, Jake Barne’s great love in The Sun Also Rises, Lady Brett Ashley, and the characters remark on this. I remember reading that novel in the sun on the steps at the Egbert Student Union at Ithaca College, 1971, reading it very fast and then starting back at the beginning, more than half in love with Brett and so miserably sorry for Jake, who’d had his dick shot off in the war, to put it as Hemingway does not. I tried to teach that novel when I was at Ohio State, and the kids really hated it, finding everyone racist and anti-Semitic, also obsessed with animal abuse, and self-pitying. How does The Sun Also Rises fit in here? Is it more than Brett’s name? And how do you read Hemingway these days?

Nina: The first thing I knew about Brett was that she needed to be named for a character in literature. I wanted to establish her lineage, that her fascination with words and stories was inherited. In a couple drafts she was named Tess, and I fiddled with Claudine. But Hemingway seemed such a nice contrast to her specialty, Emily Dickinson — both deal in unrequited love, but in very different ways. As for how I read Hemingway, I insist on loving him despite all the upsetting attitudes and content. For me the most important book is A Moveable Feast, which in ways is an apology for so much that came before in his writing and his life. And of course there was the time he lived in, and all his unbearable pain. Plus thousands of beautiful sentences.

Bill: Every sentence, perfect, it’s true. I always end up talking like him, all those simple declaratives and biblical lists. There are a lot of other literary references in the book, from Emily Dickinson to W. B. Yeats, the Bible to Oscar Wilde, and beyond, and of course they help establish Brett’s character. She’s an English Professor, after all. Does literature have other roles in this book? Did it have a role in the process of making it as well?

Bill: Every sentence, perfect, it’s true. I always end up talking like him, all those simple declaratives and biblical lists. There are a lot of other literary references in the book, from Emily Dickinson to W. B. Yeats, the Bible to Oscar Wilde, and beyond, and of course they help establish Brett’s character. She’s an English Professor, after all. Does literature have other roles in this book? Did it have a role in the process of making it as well?

Nina: The fact that she was studying literature gave me the opportunity to overtly refer to literary techniques. And it let her reach for lines from classic literature to underscore or make sense of what she was feeling. I think that if Brett weren’t so steeped in literature she might be able to make more practical decisions. Instead she’s drawn toward the romantic, the tragic. She has the natural expectation that her life should unfold like a novel.

Bill: And so it does. Clothes play a role here. Brett’s and others. They get wrecked, they get bought on sale, they have brand names, they expose, they conceal. Do you dress your characters with intention, or is it more natural than that?

Nina: Natural, I guess, though I do make a concerted effort to include as much physical detail as possible. In my mind story tends to unfold like a movie, and I like to work on creating the visuals. One thing I remind my students is that they’re creating a world, a picture, in the reader’s brain. They are responsible for set design, and costume design as well. Not that you want to describe the clothes down to the last button. Just enough, a word or a color, so that the picture forms. And in this book, so many of these moments where the clothes are worth mentioning underline the contrasts between the characters, not to mention the financial state of the moment. Ladd and Daniel are Brooks Brothers and J. Press. Brett is Filene’s Basement. Charlie, who eventually Brett marries, is his own bohemian brand, impossible to pin down.

Bill: Oh, that dreamy Charlie. I was drawn forward in the novel by Brett’s romantic tangles and indecision, her good angels playing against her devils, desire battling practical considerations. Why do we have so little control over these things, and how does that reality play in your book? Brett almost blames desire for Charlie’s death—if she hadn’t wanted him, gotten him, he’d still be here.

Nina: I don’t know, Bill, why do we do that? The devils are just so much more compelling. Especially when you’re young. Also we imagine that our choice between angels and devils represents control over our lives, when really there is no control. Brett can’t control the fact that she’s in love with Charlie, and she can’t help pursuing a relationship with him even when it’s clearly not what’s best for her, or him for that matter. Eli’s family can’t control his illness, or their reactions to it. There’s a great line in E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, which Brett paraphrases: the only tense that’s impossible to know is the conditional, what might have been. At the same time it’s a tense that’s impossible to reach for, especially when you’re blaming yourself for where wrong choices led. That’s the world where the mess you’ve created doesn’t exist. In many ways that’s the tense where grief lives, and it stems from the illusion of control: if only you’d done one thing differently, the current tragedy would not have occurred.

Nina: I don’t know, Bill, why do we do that? The devils are just so much more compelling. Especially when you’re young. Also we imagine that our choice between angels and devils represents control over our lives, when really there is no control. Brett can’t control the fact that she’s in love with Charlie, and she can’t help pursuing a relationship with him even when it’s clearly not what’s best for her, or him for that matter. Eli’s family can’t control his illness, or their reactions to it. There’s a great line in E.M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, which Brett paraphrases: the only tense that’s impossible to know is the conditional, what might have been. At the same time it’s a tense that’s impossible to reach for, especially when you’re blaming yourself for where wrong choices led. That’s the world where the mess you’ve created doesn’t exist. In many ways that’s the tense where grief lives, and it stems from the illusion of control: if only you’d done one thing differently, the current tragedy would not have occurred.

Bill: Fate, and all of that! Well, to slip from the sublime to the contemporary, cell phones play a role here, just as for better and for worse they do in our lives. Has technology changed literature?

Nina: Yes, because cell phones solve so many problems! The very reason they are helpful in life makes them troublesome in stories. I remember listening to a segment on NPR about the television show The Americans, which is set during the Cold War. The writers remarked on how refreshing it was to write about a time before cell phones, because they could create narrative issues that cell phones would have solved. At the same time, in the present day it’s more immediately alarming not to be able to reach someone. So that creates a panic unique to this period in history.

Bill: Not fair, but I know you and know that many elements of the book could be read as autobiographical. How do you negotiate the line between life and fiction? Is it a simple thing for you, or fraught?

Nina: Autobiographical isn’t quite the word I’d use. I borrow things from real life, things I know and remember, and then I change them wildly. In this novel, it’s the places — Boulder and Cape Cod — that are most true to my own life. In general, what I find when I draw from my life is that it’s the first draft that most closely resembles what actually happened. Over subsequent drafts the story moves further and further away from my own memory, and closer to what would work best in the novel. As far as fraught-ness, in the moment of writing it’s very easy to draw from real life, and real people. It’s afterward that worry sets in.

Bill: Speaking of fraught-ness. What’s it like being married to a fellow writer? And then killing him off in a novel?

Nina: Satisfying on both counts! No, really just the first count. Anyone who knows David and reads the book will see that he and Charlie have very little in common apart from handsomeness and a love of salt water. David is ambitious, a work horse, and also steadfast and loyal, while Charlie is a will o’ the wisp – an expression that would never be used to describe my husband.

Bill: He’s more of a Dave o’ the beer, it’s true. What’s your writing schedule like?

Nina: Lately it’s been pretty lame, to tell the truth. I have been focused on my teaching, and also recovering from a period of very high production. But when I’m at my best the schedule is daily, every morning, with a thousand-word minimum. I am hoping to get back on that track soon!

Bill: You write in several genres, and sometimes under different names. Tell us more about some of your other projects.

Nina: I have a young adult novel coming out in October, under the illustrious last name Gessner, first name Marina (my actual first name).

Bill: No way.

Nina: Way. Marina Gessner’s novel, The Distance from Me to You, has received some great prepub reviews and is also a Junior Library League selection.

Bill: I’m writing as Willy Gessner these days. Funny world! Now, you and I have the same editor, the beloved Kathy Pories at Algonquin—what’s your process working together?

Nina: O Kathy! My Kathy! She is just simply the best. So smart and kind. The kindness piece for me is necessary, because I am a thin-skinned artist. She is fantastic at not pulling punches but not letting the punches do damage. Our process is that I write a book that’s not good, and she makes me write it over and over until it is good. She is never afraid to delay publication so she can make me write another, and then another draft. Don’t you feel, as her author, that you are safe from writing a bad book?

Bill: I am never safe from that, but I adore Kathy, very grateful to have her in my life and behind my pages!

Nina: Her taste and her instincts are so fine. She has her PhD in English Literature. She is an animal lover and a runner. I love her madly.

Bill: As she loves you. And as we all do, here at Bill and Dave’s. Thanks for talking. The scuba team is here to whisk you to the Bill and Dave’s submarine. Safe travels back to Wilmington, NC! And best of luck with the new book!

Nina de Gramont is a novelist and short story writer. Her first book, the short story collection Of Cats and Men, won a Discovery Award from the New England Booksellers Association and was a Booksense selection. Her novel Gossip of the Starlings was also a Booksense pick. Her second novel for adults, The Last September, is finally here.

Nina has also written three novels for teens – The Boy I Love, Meet Me at the River, and Every Little Thing in the World, which was an ALA Best Fiction for Young Adults. Another novel for teens is forthcoming with Penguin in October, under the pseudonym Marina Gessner. The Distance From Me to You is a Junior Library Guild selection.

Essays and short stories by Nina have appeared in a variety of magazines including Seventeen, Redbook, and the Harvard Review. Nina lives in coastal North Carolina with her husband and daughter, and she teaches Creative Writing at UNCW.