David Gessner's Blog, page 101

October 20, 2011

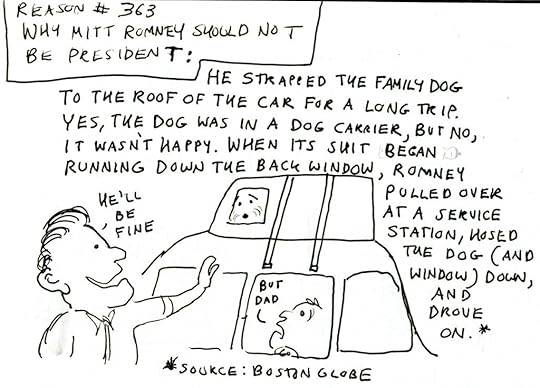

Reason 363 Why Mitt Romney Should not be President

October 18, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: The Journey Years

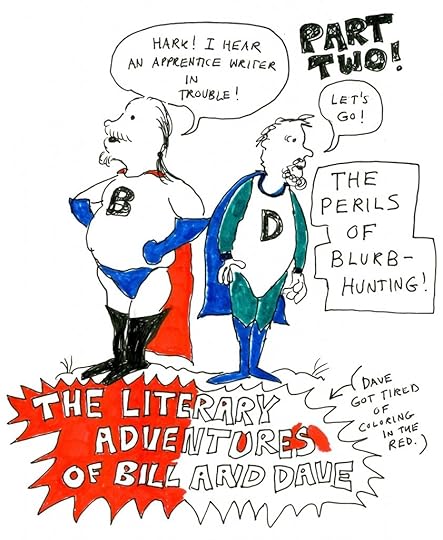

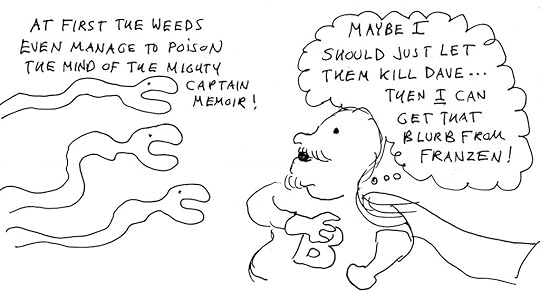

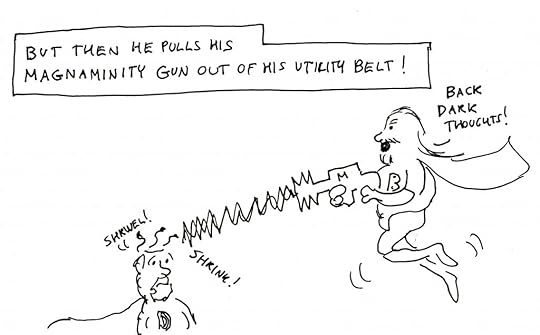

Bill at the forge

Dave has talked in an earlier spasm of bad advice about the 10,000 hours an apprentice at anything must put in. Now, perhaps, it's time to talk about the artist's or writer's journeyman years, or better, journeyperson years, or better yet, just Journey Years. These are the professional years after your apprenticeship has been served, the cruelly harder but perhaps much more rewarding years. A friend says that after apprenticeship (after, say, the MFA is done, or once the first book is out there, or whatever marks the transition for you in your particular set of circumstances), that after the apprenticeship comes something he calls the ten years, or that Dave might call the ten more years. The Ten More Years. Our graduating class of 2011 apprentice writers will surely write new books and perhaps publish them in those ten journey years that will take us to 2021, but the lessons will keep coming: triumph, disappointment, joy, heartbreak, success, failure, pleasure in the process, pleasure in the success of others, heart-stabbing envy more often. In most cases, the positive items on the list will have to float the far greater volume of the negative. But positive is more buoyant than negative, so no matter, probably you'll float. It's really your choice whether to be miserable or happy while you bob along.

Many lessons, much more to learn: that's the journey years. It's like Super Mario Brothers, a video game I played once back in the stone age of video games, maybe 16 years ago. I played it with my little niece, who is in college now, and discovered playing it that even an old uncle had to suffer quite a bit to get through Level One, which she had mastered. But I got it after a week or so, and I remember the day my little Mario man climbed that last ladder and up to that elusive trap door that led through the ceiling into … into Level Two?!

One's sense of triumph, of finality, of the end of things, of achievement even, is short-lived. Because there it suddenly is, all around you: Level Two. And you and your little Mario man have to learn a whole new set of customs and manners and self-control, just to follow this six-year-old girl into levels three through 10,000, or wherever it stops [1]. Being graduated from one's apprenticeship is like that. Proud as heck, you open the hatch door in what has been the very ceiling of ambition (your MFA! Your first book! Your second book! That big prize!). You stick your head up through the spider webs, expecting sunshine and bluebirds, but when you look around there's just a whole new world of shit, and I mean it.

My wife once told me a Zen story she'd read. Student asks the master: What is it like to be enlightened? master says, "Well, before I was enlightened I had to wash the dishes, cook meals, clean the house. The eager student says, "And after? After?" "Oh," says the master, "after I was enlightened I had to wash the dishes, cook meals, clean the house. "

Ten More Years. Jazz musicians talk about dues paying. You play in the ratty clubs, midnight shift, short pay, no respect, make your way to the next thing, bigger clubs, hotter sidemen, harder riffs, the 2 a.m. shift. There's no end to the gradations and degradations. R.V. Cassill talked about it another way for writers: you've got to make your first million words. That's just your apprenticeship, then maybe a million more for your journey years. A million beautiful, finished words. A hundred thousand sentences, more or less. Ten thousand paragraphs. Something like 3300 manuscript pages. Not quite two War and Peaces or Infinite Jests. Five Moby Dicks, approximately. Eleven The Catcher in the Ryes. Ten More Years. Enjoy!

No, really, enjoy. It's not a sentence but a blessing. Only a few get to do it. And that means only a few understand it, will understand what you are up to and up against. It's like having a secret dinosaur friend. And you don't go around telling just anybody about your secret dinosaur friend, right, Bronto?

To make money you'll be doing other things for a while or for life, be around people who may not get it. Your best work may fall into the hands of people who don't get it. So make sure you keep your apprenticeship gang around you, that you have writer and artist and artisan friends, and that they join you on the journey.

As Joyce Johnson has written in her brilliant memoir of Jack Kerouac, Minor Characters: "Artists are nourished more by each other than by fame or by the public. To give one's work to the world is an experience of peculiar emptiness. The work goes away from the artist into a void, like a message stuck into a bottle and flung into the sea."

Nourish each other. That doesn't mean workshopping. Probably you're done with that, Journeyperson. No, I'm not talking about more school. I'm talking about just staying in touch, reading each other, responding to each other, writing fanmail as the work of friends appears in print, not hating better writers anymore like some cloddish apprentice, but admiring them, not disdaining the less talented, but nurturing them as you can (possibly including actual meals). All this in order to learn how to admire yourself, nurture yourself. All this in order to have friends in the game. All this to help yourself get it: this is what you signed up for. This is your reward.

We're all experts now. Our masters have taught us all they know, and it turns out not to be all that much. Turns out we arrived at our apprenticeships with all the equipment we needed, and the enlightened ones just did their best to show us how to use it. Now, as the journey really begins, there's no one to guide the way. And there is nothing but ways. Ten More Years. And then guess what? Ten more! And so I end on a note of mathematical anomaly. Your Ten More Years might very well take twenty, or thirty, or seventy, or even more than that[2]. Because, in fact, there's no such thing as mastery when it comes to the arts.

It just looks that way from outside.

[1] It stops at death.

[2] See footnote 1.

The Meaning of Lance

[image error]To lose a testicle is to lose a friend.

I wrote that sentence about twenty years ago, soon after moving out to Colorado in the wake of going through an operation and radiation for testicular cancer in Worcester, Ma. A book about my cancer experience poured out of me (and to be honest I haven't stopped writing hard since.) Soon I also started biking, mostly up steep hills.

Not much later a more famous case of testicular cancer made the headlines. Lance Armstrong also did a little biking after he lost a ball. About ten years ago I wrote, but never published, the essay below about Lance…..it's far too long for a post so you are excused from reading it if you are busy. Just skim! These days I am more cynical about Lance, and the possibility of his doping, than I was when I wrote the piece, but I still think there is something archetypal about his return from near death.

Here it is:

The Meaning of Lance

I pass ponderosa pines, the fallen yellow leaves of aspen turned too early, and three bucks with velvet antlers nibbling on the hillside grasses. I'm back in Colorado, where my recovery began ten years ago, and I'm on my bike heading up toward the abstract outline of mountains made hazy by rainclouds, climbing a hill that I would have once thought too steep. My profession requires that I spend much of my time locked inside the musty attic of my brain, but for the next three weeks my job is not the usual one of keeping my butt in my chair and my eyes facing a computer screen. Instead I will keep that butt on a bike seat—-at least when not standing up to pedal–and will face the mountains I'm climbing. The impulse to make stories, however, can't be entirely stifled and while my fingers grip the handlebars and my chest heaves and my feet and legs turn the gears, my brain has taken on a secret project. I am going to discover the meaning of Lance.

By this point he has ascended to single name status—Lance—and over the last few years there have been countless articles about him, as well as his own wildly popular autobiography. There are obvious reasons, besides sheer athletic brilliance, that he has attracted our attention. But I want to dig below the obvious, to try and understand why this individual has meant so much to so many and–even more importantly for my current purposes of this very personal essay–why he has meant so much to me.

* * *

It happened years ago, a week before my 30th birthday. It wouldn't be too much of a stretch to say I lost half my manhood right as I was on the verge of becoming a man. In fact, with hindsight, I can see the role the loss played in the becoming. But at the time I didn't see that. All I could see was that a doctor was telling me something that couldn't possibly be true—I was too young and strong, after all—and a few weeks later the same doctor was cutting me open and dislodging my right testicle from its home of 29 years.

Each year in the U.S. approximately 7,000 men, mostly very young men, are diagnosed with testicular cancer. Terry Tempest Williams celebrated her clan of one-breasted women, survivors of breast cancer. I, less poetically, am a member of the clan of one-balled men. Lance Armstrong is the most prominent member of our tribe, and the comedian Tom Greene perhaps the most annoying, but there are hundreds of thousands of others, each with their particular prognosis, for better or worse, and each with their particular story.

Here are a few of the particulars of my story. Kneed in the groin during a game of pick-up basketball, I was surprised when the pain didn't go away the next day, more surprised when it lingered for weeks. A month later I was in the doctor's office, standing in front of a man who I'd soon come to regard as my savior, as he recited sentences to me that were the stuff of TV movies-of-the-week. Within ten days the same man was cutting me open, and I was awake to watch it, since the doctor had discovered that I also had malignant hypothermia, a rare condition that made it dangerous, and potentially fatal, for me to be put under with anesthetics. Instead I was given a spinal, as many women are during childbirth, my lower half numbed so that they could make the slit in my abdomen through which to extract my testicle, reeling it in with the spermatic cord. Not only was I half-awake during the operation, I also had someone to talk to. My girlfriend of six years, Rachel, was a medical student at U-Mass, the hospital where the operation took place, and the doctor had asked her to observe the entire procedure, if it was okay with me. It was, and so Rachel was there as a firsthand witness to my half castration.

I stayed in the hospital for a week after the operation and spent most of that time awaiting what Rachel and I came to call "the verdict," that is the results of the pathology tests. The word I finally got was good indeed—-a seminoma, the best cancer flavor, possible—-and no other operations would be necessary. I celebrated my 30th birthday with the news that I would live, but, despite the positive prognosis, I reacted poorly to the required month of radiation treatment, which seared the cells lining my intestines. By the next fall, four months later, I was well enough to leave behind both my doctors and Rachel, moving to Colorado to attend graduate school.

Colorado was the perfect place to recover. My tests continued to confirm that I was "clean," and I began to hike the trails, then run them. It was during my second year in Colorado that I discovered biking. I loved climbing the roads outside of town on my bike, up into the mountains. I wasn't a great rider, but I was a dogged one, rarely missing a day. It made me feel strong and occasionally I rode shirtless, baring the permanent blue tattoos that had been burned into my torso as guides during radiation treatment. Then, in 1994, a year after I began to ride, two events occurred that changed my life. During the first week in April I began to date the woman who would become my wife, and, later that week I got the phone call with the news that my father, at 56, had lung cancer. He would only live for three more months and throughout those months, when not back East tending him, I spent hours on my bike, climbing up into the hills, enjoying the pain in my still-live muscles and the respite from thought.

* * *

It was two years later, at the end of my fifth summer in Colorado, that I heard the news about Lance Armstrong. I'll admit that I immediately thought what a lot of people thought: this guy's a goner. By then I'd been through enough, between myself and my father, to feel like a bit of a cancer pro, someone who knew what was what when it came to the dark art of cells dividing and tumors growing. But you didn't need any expertise to see this guy was dead. It wasn't just in his testicle, but in his lungs, and, worst of all, in his brain. He was given a forty percent chance of surviving and, as he wrote in his autobiography, "frankly some of the doctors were just being kind when they gave those odds." I had gotten to know both good cancer and bad cancer over the previous five years, and this was definitely bad.

The severity of his disease has a lot to do with the meaning of Lance. In The Denial of Death, Ernst Becker writes: "The hero was the man who could go into the spirit world, the world of the dead, and return alive." There have been many athletes who have had cancer scares, but this was more than a scare. When discussing the hero returning from the underworld, Becker cites not just the obvious Christian myths, but the "mystery cults of the Mediterranean, which were cults of death and resurrection." Given the extreme severity of Lance Armstrong's condition–-for instance the brain surgery required to remove tumors–his was as much a resurrection as a recovery, and what elevates him from idol to hero is his time in the land of the dead. Human beings have always heaped praise, even worship, on those who have gotten close to the place we all fear, and then returned. In his book Armstrong expresses anger with those who gave him up for dead, but to a certain extent that was everyone, at least every objective outside observer. The most compelling comebacks in sports are those where everything has been lost, where the athlete, or team, is dead. We thrill when an athlete, Michael Jordan say, performs well in the clutch, that is when facing elimination. Sports, as has too often been said, merely mimic the greater life and death heroics of war, and though athletic defeats may be described as crushing and devastating, all is not lost. In Lance's case the metaphor was stripped away, and those words became real.

Before my own operation the whole notion of death seemed theoretical, and there was still a chance that my tumor wouldn't be malignant. After the operation I had a week of uncertainty over my fate, but then, a week later, I was given a 90% chance of survival, which changed everything. I suppose I could claim to know how a dire prognosis feels because I was so close to my father during his last weeks, but that wouldn't be true either: no matter how close we are to someone there is always the slight relief that it is not us—-and we can never really know how that doomed other feels. And so I can only know how it must have felt for Lance the way any fan knows an athlete: through empathy, with all its limits. That is one of the thrills of sports, after all. We become the athletes we root for, but there is always safety in the fact that we're not the ones facing the danger, safety in the fact we're sitting home on the couch. And this is important for the Lance myth, too. Because the hero is someone beyond us, someone who has achieved more than we ever will.

When entering into a discussion of this sort, particularly when the subject is cancer, one has to be wary of talking about "lessons" or "meaning." "Everything happens for a reason," was a phrase that people parroted at me when I was sick until I wanted to jump out of my hospital bed and throttle them. "Yes, it happens for a reason," I wanted to yell. "And the reason is my cells divided and a tumor formed and that's the reason and there is no other!" In his autobiography Armstrong is quick to point out the role of luck in cancer survival. His doctors tell him that they have seen people with great attitudes and outlooks die while ornery bastards lived. And, likewise, Armstrong, for all his strength and fitness and his innate ability to breathe better than a normal human, admits that he, as strange as it sounds, ended up getting lucky. Just as no one knows the reason the cancer came, no one knows why, in his case, the chemo worked and the cancer went away.

A popular cancer myth is that of the survivor blessed above other human beings, a creature who smells every rose and smiles sweetly at every sunrise. Though anyone who has almost died feels a powerful resurgence at the simple fact that they will live, in most people this fades quickly. What doesn't fade as quickly, it seems to me, is an undercurrent of fear, of dread, which if funneled effectively, can be a productive thing. "If you can still move you ain't sick," Armstrong told himself, and some of his worst times occurred during the relatively indolent period after he had been declared clean and before he had re-committed to being a champion racer. It was when he began to train—and train with ferocity—that he came alive again. I remember my own experience of writing myself into a near frenzy in Colorado a few months after my radiation treatment. The survivor, particularly the young survivor, is suddenly aware that there are deadlines. While I think the world-appreciating survivor is, for the most part, a myth, I do believe that in some cases cancer is life's starting gun. A sense of urgency prevails. There is little time. We must make use of it.

* * *

Today, through a stroke of good luck, I come a little closer to Lance.

For the last ten days I have been climbing up into the mountains on my rental, a Trek mountain bike. The Colorado weather, edging from late summer into early fall, has been perfect, and the fires that turned the sky rubbery have passed. Our lives are idyllic: we live in a small cottage facing the mountains and yesterday, near dawn, I watched a bushy-tailed red fox amble its way across our backyard. But the highlights of my days haven't been a pastoral contemplation of the hills, but my ascents into them. I ride alone sometimes, steady but slow by my old standards, and when I ride with my Colorado friends I try to quell my own competitive instincts, keeping behind, telling myself to hold back, just getting my legs used to the exertion and my lungs used to the altitude.

But now, thanks to a new friend, I let loose a little. I met Doug a year ago when my wife and I were biking up one of the local canyons. I was standing over my bike by the side of the road, resting while trying to fit my water bottle back into its cage, when he pedaled up beside me. He asked if everything was all right and I said it was. He rode a fancy racing bike and had on lycra shorts and biking shirt, and what I-—always a kind of low tech guy—-really wanted to say was "What's it to you buddy?" Not long after, my wife and I pulled over to swim in one of the streams while he rode off up the canyon. When we got back on our bikes we turned off on a road to another canyon but by then the stranger had doubled back and caught us right before a particularly steep ascent. We were taking a quick break at the bottom of the hill and he pulled up next to us. "Do you two know where you're going?" he asked. Now I really didn't like him. Who was this guy to ask me about my hills? As it turned he was the owner of the bike shop that had rented us our bikes, and he was just making sure that a couple of out-of-towners weren't getting in over their heads. We started to talk and my wife mentioned that I'd once written a book about the area. Then he said something that might be normal fare for Stephen King or John Grisham but that I had never heard before. "You mean the book I started reading last night?" he said. The book was personal and autobiographical and he pointed at my wife. "You must be Nina and you two must be out visiting from your house on Cape Cod." After we talked for a while, we started riding up the hill together and I asked him about his bike. "It's my Lance bike," he said. "The same one he won the Tour on last year." I took that statement at face value, naively assuming that he had somehow gotten his hands on Armstrong's actual bike. What he meant of course, as I learned later, was that it was the same model Armstrong had won the Tour on: a trek 5900 with a carbon fiber frame that cost around 4,5000$.

Today I am on the Lance bike. The bike only weighs 16 and a half pounds and I, used to heavy mountain bikes, feel as if I'm flying up the canyon. Doug suggested I try the bike after I told him that I had been doing a lot of thinking about Lance. He is a former bike racer and as we pedal he gives me pointers on my technique. I lurch a little too much, and sway my shoulders. "Watch video of Lance climbing," he says. "His upper body is just a passenger." On the other hand, Doug tells me I'm a natural climber, and compliments the way I mash the gears when I stand. That compliment, as well as the bike itself, makes me feel stronger, and we easily drop our third riding partner, a friend whom I have been trailing up hills for the last week. For a while I keep the bike in the same gear Lance uses while he climbs, but where he spins steadily, I strain. Still, I feel good. I try to keep my shoulders from swaying and push down even harder on the pedals.

I love to climb, and love to watch real climbers climbing. Often there is a sense of controlled fury to ascents; a teammate of Bernard Hinault's once described that great champion's quality of "destructive rage." Armstrong himself wrote of "the primitive art of climbing" and the raw, basic nature of the climb is vital to the Lance myth. Biking is a sport we all knew as children and still know—"it's like riding a bike"–yet racing is a foreign sport of pure struggle without the usual lines or hoops or rackets or complex rules. Given our culture's obsession with balls of all sorts, the coverage of Armstong's comeback might have been even greater if a star quarterback or outfielder had recovered from cancer and near death. But it would have been less metaphorically apt. If cancer strips sports of its metaphors then the climb is both the thing itself—a raw ordeal of suffering—and an activity chock full of symbolic implications. Climbing up from nothing to something, climbing out of a deep hole, climbing as the embodiment of the ability to endure pain. Though the time trials are vital to the Tour de France, it is the series of climbs that are the heart of the race. The question the Tour asks of you, according to Armstrong, is, "Who can best survive the hardships and find the strength to keep going?" What could be simpler? Almost a pure distillation of sport. And what better metaphor, not just for cancer survival but for the more mundane victories of everyday living: the need to go on, to battle upward, to survive. In fact, the sport so perfectly fits the story that at times metaphor and the thing itself blur, just as they do when you're riding. Armstrong wrote: "I tried to tell myself that the fight for my life was a lot more important than the fight to win the Tour de France, but by now they seemed to be one and the same to me."

Of course the Tour is not just a climb, but a race, which means beating others. Athletes often feed and nurture the chips that grow on their shoulders, since these chips fuel them, and the chips have to be invented if none are there at the moment. Armstrong began his career as an almost raw embodiment of "destructive rage," breaking other riders, driven by an urge to show the bastards. "When you open a gap, and your competitors don't respond, it tells you something. They're hurting. And when they're hurting, that's when you take them."

Today, as my legs pump the pedals, I have no illusions that I'll be pulling away from Doug. He is an ex-racer, and could likely drop me at any moment. A series of little stars, the sort used to reward kindergardeners, shine up at me from his bike's crossbar. Each star represents a time Doug has beaten his regular biking partner during their countless races to Deer Crossing signs or town borders. When I lived here I often raced up the hills with friends, the competition pushing us to go faster than we ever would alone. We weren't winning any yellow jerseys, or beating Hinault or Ulrich, but it meant something to be the first one up, at least it meant something in our own small worlds. Ernest Becker writes: "An animal who gets his feeling of worth symbolically has to minutely compare himself to those around him." Doug's stars help him get up the hill, and give sense to an essentially senseless thing. For those of us who are not ever going to win, or even compete in, the Tour, the victory is in the activity itself, but even if the goal is something beyond ego it doesn't hurt to enlist ego to help get there.

It's on the downhill home that I learn something else about riding: the bravery required to hurtle down on such thin wheels. The bike is acutely responsive, both to my movements and to bumps, and I am too much of a coward to let go of the brakes for long. Still I get a sense of the speed—racers can reach seventy miles per hour on these flimsy things—and the trusting courage it must take to ride brakeless down such hills.

* * *

We are told that we must not hero worship. And this is a sensible admonition. But there is something we have abandoned along with the worship. That is hero use.

So: in Lance we have an archetypal hero returned from the land of the dead and a sport well suited to the myth, both in its metaphoric and actual elements of struggle and pain. What else makes Armstrong's case particularly compelling? Well, there's also the myth of transformation. Around the time of my own sickness, Robert Bly's Iron John was quite popular, and one of that book's central stories was that of the boy who lost his golden ball, and then suffered a deep wound, on the way to becoming a man. The Lance story provides us with one of the basic pleasures of narrative: watching our protagonist change and grow. As Armstrong himself writes, there was a Before Lance and an After Lance, and part of his story is the way that his cancer prompted a kind of accelerated maturation. The Before Lance, according to our myth, was an angry bull, at times a study in wasted energy, always going out hard and early, trying to prove he was stronger than everyone else. This character was a brash young wildman, who attacked at any time, seemingly at random and out of spite, and who, when he won, flashed the Texas Longhorns "Hook 'em horns" salute with both hands. The After Lance, on the other hand, is a mature, almost scientific tactician, a leader who knows how to make best use of his still prodigious strength and energy. And what separates these two Armstrongs? Cancer. It is narratively perfect. Our hero's trial. His wound. His lost ball.

On the simplest level, Armstrong's transformation was a physical one. Before the cancer, he weighed 175 pounds, bullish for a biker, but the chemo and inactivity stripped him of muscle and he made his body anew. "The upper body is the passenger," Doug told me, so why waste time putting on showy muscles that will have to be carted up into the hills? The new body is sinewy and lean, 158 pounds, and the new face, self-described, is "hawkish." (To get the idea of what a difference this makes bike up a steep hill sometime and then try it again with a 17 pound weight in your backpack.) But even more important than the new body, according to our story, is the new mind. This mind knows some of the hard-won secrets of the adult world. It knows the value of patience, when to hold back and save energy, and the value of consistency, as well as, to some extent, the value of diplomacy among the other riders in the peloton. And it knows that great goals are not achieved all at once but through accretion, the gradual piling on and up of day after day of dull and repetitive work.

"I wasn't as good at the one day races anymore," Armstrong writes. "I was no longer the angry and unsettled rider I had been. My racing was still intense, but it had become subtler in style and technique, not as visibly aggressive. Something different fueled me now—-psychologically, physically, emotionally—-and that something was the Tour de France…..I was willing to sacrifice the entire season to prepare for the Tour." In other words he was able to hold back, to plan ahead, to give up short term pleasure in return for long term gain. And isn't this a change we all go through, or imagine we go through, if we hang around long enough? Isn't it, for the purpose of our story, something like the getting of wisdom?

* * *

While my own story wasn't nearly as heroic or resonant as Armstrong's (whose is?) it did divide my life neatly into a before and after, and was not without some mythic overtones. I grew up in the industrial city of Worcester, Massachusetts, and, having lived my whole life in the East, moved back to my hometown the year before I got sick when Rachel was accepted at U-Mass medical school. In the fall after my cancer, once I'd recovered from the radiation treatments, I drove an unregistered Buick Electra from Worcester to Colorado. The trip mimicked the classic American movement from east to west, a chance to make myself anew. Along with my right testicle, I left many other things behind in Worcester: my mate of seven years, generations of family and family history, my old job and old friends. My new home was a small blue cabin tucked in the cleavage of a canyon that was called, appropriately, Eldorado. Though lonely at times and still anxious about my health, I often felt exhilarated as I went about learning the names of the local plants and birds—all new to me—and embracing my new Western life.

I had come to Colorado, not to ride my bike, but to write, and each morning, in the cool of the canyon, I got up and walked to my desk, where a book about Worcester and cancer poured out of me. Though, as I say, I am loath to draw too many cancer "lessons," I felt at least two of the things that Armstrong reports feeling. One was a daily urgency—-I was being given a second chance and I would damn well take it—-and the other was the determination to finish a long project, that is a book, not a mere story or essay or fragment. As it turned out it would take years, not the months I'd optimistically imagined, but that book would eventually be completed.

* * *

Yesterday, just after I'd finished my morning ride, Reg Saner came by for a visit. During my first years in Colorado Reg was my wise man, my Merlin. I first got to know Reg as a poet and professor, only later learning he was an outdoorsman and Korean War vet. White-haired with an aristocratic nose, Reg has a noble bearing and an aggressive intellect and, though he was a great and kind teacher, he could also be somewhat intimidating in class.

We sat behind my cabin and ate bagels and peaches, and I told him about my Lance project. Reg himself was an ardent biker, making it a point to climb regularly into the mountains surrounding the town. He listened carefully and then mentioned something I hadn't considered.

"You might think about Greg LeMond's story, too" he said. "He's Armstong's precursor in more than one way."

He reminded me of LeMond's victory in the Tour de France in 1986, the first by an American, and then of the tragic hunting accident the next year that nearly killed him. LeMond was only a few minutes from bleeding to death when a massive transfusion and operation saved his life, and his recovery was long, slow, and painful. Just as experts wrote off Armstrong, they assumed that LeMond was finished as a biker, but he vowed he would be back and two years later, in 1989, he won the Tour again.

"That final time trial might have been the most dramatic comeback not just in the Tour but in all of sports," Reg said. "Going into that last race he was down fifty seconds to Fignon. It was a short race—24 kilometers—and the experts said it was impossible to make up two kilometers a second. He rode the fastest time trial in history and won by eight seconds."

I wondered if Armstrong had found any inspiration in LeMond's story, in having a predecessor and role model when it came to doing the impossible. Of course more recently there has been some discord between the two champions, in part because of LeMond's comments about Armstrong's association with an Italian doctor notorious for doping. Unfortunately, the specter of drugs hangs over the Armstrong story, threatening to re-write it at any minute. I mentioned this to Reg and we agreed that we would feel a deep sense of disappointment–even betrayal–if he ever tested positive. But the fact is that Armstrong has been tested for performance enhancing drugs again and again, and continues to come up clean.

* * *

A bear has been getting into the neighbor's trash. Drought is part of what is driving the bears down from the mountains, but so is time of year. Fall is the foraging time, and fall is coming. A time of activity and gorging, before the long burrowing of winter.

The mornings are cool now and I get up early and work in our backyard, using a tree stump as desk and watching the roseate hues reflect off the red sandstone mountains we call the flatirons. Each day, before I ride up into the hills, I bury myself in books of myths. I am re-reading the Armstrong autobiography, but I also dip into myths of heros and heroines who have spent time in the land of the dead and returned to this world. In a compilation called Parallel Myths by J.F. Bierlein I read the Kenyan story of Marwe, the Babylonian story of Ishtar, and the Egyptian story of Osiris and Isis. Every culture, it seems, has its myths of those who have died and come back. As well as more well-known tales like Aeneas crossing the River Styx, the book also details Native American stories of the Iroquois and Algonquin. A common thread in these stories is that those who have known death once and escaped, later, when the real time comes, greet death as a familiar, an "old friend." Another thread is that the period between the first journey to the underworld and the final one is often a time of great prosperity and fecundity. Though I have not made much of the "love story" aspect of Armstrong's comeback, the myths consistently stress love conquering death. Whether this is the case of not, it should be noted that Armstrong married soon after his cancer, and now through artificial insemination using stored sperm (a method unknown in the mythic literature), has three children.

Bierlein quotes the Irish scholar Jeremiah Curtin: "A myth, even when it contains a universal principle, expresses it in a particular form, using the particular personages the language and accessories of a particular people…" Who is to say, in this non-mythic time, that Lance doesn't fill a particular role for us? Who is to say he is not the universal made particular? Even down to a certain geeky reliance on computers and gizmos, he seems very much one of us, but at the same time, by virtue of talent and achievement and circumstances, he is also something more. Thomas Mann wrote that "the typical is actually the mythical." I know a little of what it's like to live out the myth of comeback, of return and recovery. But Armstrong has lived it more dramatically and on a larger stage. And that is the role of the hero, too. To do what we all do only more grandly.

* * *

Tomorrow Nina and I return home to Massachusetts. But before we go I am taking a valedictory ride, up to the mountain town of Gold Hill. Sunshine Canyon doesn't live up to its name this morning, the clouds seeming to blossom into volcanic plumes above the mountains of the continental divide. My backpack holds raingear, extra water, and a journal, and I–-no longer graced with the Lance bike–am taking it slow this morning. Sunflowers, gumweed, and asters dot the side of the road while delicate aspen leaves sough in the wind with a sound like flowing water. Yesterday a black bear was seen on the trail only a hundred yards above our cabin, and later I found prints and scat while walking along Skunk Creek. Fall is coming fast and today almost feels like it's here.

I pedal up toward the clouds, sweating through my T-shirt as if feverish, my shoulders and thighs aching from both the morning's exertion and the cumulative exertion of the last three weeks. The ride to the dirt is hard, the ride above brutal, a 3,000 foot gain in altitude. I pass Doug Firs, a hovering golden eagle, a scolding raven. Narrative is part of what pulls me up the hill, and when the dirt finally levels out nine miles above town, the day's plot reveals itself: the clouds that have been hiding the horizon tear away to reveal the massive range that includes both Long's and the Indian Peaks. You need to get up this high to gain perspective, to really see the mountains and appreciate their range, that is how many and how massive. Today's theme, it turns out, is ascension, not just climbing but what we climb into. Like Lance, I climb so I won't die. What better way to banish both the mundane and the terrifying than through sheer physical force? If you can move you ain't sick. But it is more than that. I climb to be up here.

"The urge to heroism is natural and to admit it honest," wrote Becker. And what is heroism? Becker answers: "heroism is first and foremost a reflex of the terror of death. We admire most the courage to face death; we give valor our highest and most constant adoration; it moves us deeply in our hearts because we have doubts about how brave we ourselves would be." But the mind is slightly embarrassed, even squeamish about the notion of heroism. We make jokes and shy away from such a crass notion, and won't admit that it is what we most want. But perhaps I should quickly qualify that "we." While academics and intellectuals grow uneasy around such a gauche concept, the so-called popular mind, as Becker points out, has always embraced the heroic. And still does as evidenced by the fact that Armstrong's autobiography long perched atop all the bestseller lists. No matter what we say or how we equivocate or intellectualize, we all hunger for the rawly heroic.

For me the climax of Lance's story was not his crowning ride into Paris, but his training rides up into the mountains outside of Boone, North Carolina. Months after his final operation and the last round of chemo, Armstrong still lived in the limbo of recovery, getting physically stronger but not yet ready to commit to becoming a bike racer again. The story goes like this: several times he tries to come back, several times wavers, several times quits. But then he heads to Boone, to train with his old friend and coach Chris Carmichael. "From then on all we did was eat, sleep, and ride bikes…..I began to enjoy the single-mindedness of training, riding hard during the day and holing up in the cabin in the evenings." It is there, in the ancient and worn Appalachians, on the steep ascent of Beech Mountain, that Armstrong begins to feel whole again. And it is there, on that road where years before he won the Tour du Pont, that he sees the words, "Viva Lance" still painted, faint but visible, on the asphalt. "As I continued upward, I saw my life as a whole. I saw the pattern and privilege of it, and the purpose of it, too. It was simply this: I was meant for a long, hard climb."

Noble words, and wise ones, but for me there is something beyond–-or maybe below–words about the story of Boone. What is a comeback if not the raw wordless resurgence of life? Almost dead. But not dead. Alive. And that makes all the difference. For Armstong it meant five Tour victories, a marriage (that has ended in divorce), and three children. For me it means a pregnant wife, three books written, and ten years of life I wouldn't have lived. For other survivors it means other things, but always a basic gift, the gift of more. And, below any specifics, any achievement great or small, there is, once again, something simple and wordless. Maybe, in the end, the meaning of Lance is as ineffable as Whitman's barbaric yawp. A squall of life like an infant's. I am alive. Still alive. I was dead, the story goes. Now I am back.

I crest out on the dirt, overlooking the mountains, and then glide down into the little town of Gold Hill. Up here the early aspen patches glow a strange gold-lime, and, at over eight thousand feet, it feels closer to early winter than late summer. My legs, trained by the last weeks, are strong and my mind feels freed by the exertion. As I bomb down the hill I want to launch right out of my skin into the thin mountain air. On days like today I do feel something like the cliche I often denigrate: the appreciative rose-smelling survivor. And I can't help but feel that the descent's delight is tied to the ascent's struggle.

I have a close childhood friend from Worcester who has been Californized by many years in L.A., and who now leaves this outgoing message on his answering machine: "You have reached the house of bliss." I've never liked the message, though I'm not against occasional spasms of euphoria. It's just that "The house of trial" seems, to me, a more apt description of the world. During my stay in Colorado I've kept a picture of Armstong tacked to the wall of the cabin, the way a teenager pins up a pop star. The picture shows him pedaling in the Tour, standing over his Trek bike with his upper body as a steady, though slightly swaying, passenger. But his body is not what interests me about the picture. It's his face that pulls me in. The face is drawn, slightly haggard, the eyes somewhat demonic and the expression only slightly less anguished and tormented than the face in Munch's The Scream. It's not the face of bliss, that's for sure. But if this is what torment looks like, it's a self-imposed torment curiously close to happiness. For me it is an attractive face. For me it is the face of life.

October 15, 2011

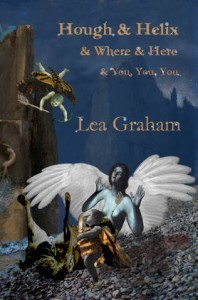

Table for Two: An Interview with Lea Graham

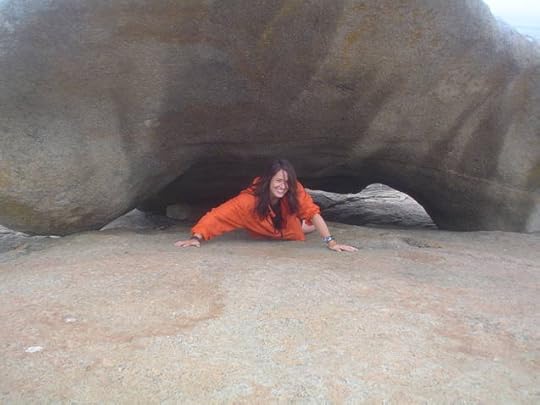

Crushed in Galicia (photo Jen O'Leary)

Lea Graham is a traveler. Fluent in Spanish, and a poet to reckon with, she also speaks wine. Her first book of poems, Hough and Helix, has just been published by No Tell books, and it is a wonder, a confluence of image and story and meaning and mood. I first met Lea in Worcester, Massachusetts when we were both teaching there (she at Clark, I at Holy Cross), and we had meals together from time to time and good conversation. So this "Table for Two" isn't entirely a fantasy, though we'll make free with the location:

Lea, in answer to my query: "A beach in Cadiz (the oldest Western city, you know, because of the Phoenician trade route, I believe). We'll eat tortitas de camarones (small thin crispy omlettes with tiny prawns), calamares en su tinta (squid in its ink), all kinds of shellfish including sea urchin, crab and lobster…

BR: And to drink?

LG: A bottle of Albariño. It is white wine from Galicia and very refreshing!

The beach at Cadiz, and dinner.

(A man in a white shirt arrives carrying a basket full of the very foods Lea has mentioned, and a slightly chilled bottle of the exact wine. He and Lea chat in rather formal Spanish without a glance at me, while he pulls an ingenious folding table from his basket, sets it up low in front of us, snaps a tablecloth in place, produces good glassware, real silverware, linen napkins, and then he lays out the food: freshly caught, freshly cooked. Very carefully, he pours us tastes of the wine. Lea likes it, nods. I nod too—it's crisp, cool and exactly what you want to drink on the beach. He fills our glasses. When he's done he retreats to an attentive spot behind us. We toast, we drink, we look out over the Bay of Cadiz and the great Atlantic Ocean. Somewhere down the beach there are a couple of young men playing guitars. At first, it sounds like traditional flamenco-inspired music, then Lady Gaga's "Poker Face." An older woman with pink-tinted hair and her small terrier trot by us. We are reminded that even in the oldest part of the old and formal world, the new and transient are never far away. The wine is nice, very, nicer with every sip.

BR (ready with his fork, hoping for a long answer): Tell us about the genesis of your new book, Hough and Helix & Where and Here & You, You, You.

LG: The book started as a confluence of several things. I was re-reading Anne Carson's Eros: The Bittersweet and thinking of the way that desire was written as a kind of space. Since I'm really interested in "place" and all that accompanies it, I was immediately caught by how this abstract notion was figured in "reach" or "edges," etc. I was thinking…

BR: Reach? Edges?

LG: Well, the notion of "crush" and the geography that makes it possible were the things I was interested in. Most of the poems have little to do with any kind of satisfaction or culmination. So, yes, "reach" is the action where all happens—where our imagination happens. Not "touch" or "receive." "Edges" are precarious places and also a place of curiosity and mystery. Also, this works for the destructive notions of "crush," too. "Reach" embodies a longing and lack. When you're "on the edge," it is a place of potential destruction.

BR (tasting the tortitas, long sigh): Thanks.

BR (tasting the tortitas, long sigh): Thanks.

LG: So. I was thinking about how music (Miles Davis, James Brown) and weather influence the state of being—either as despair or as the imagination that accompanies desire, hence, "crush," as in having a crush. I was also watching a lot of Jim Jarmusch films and thinking about how he manages to suspend scenes in silence. Those seemed like the space of eros to me. A couple of scenes in the film Stranger than Paradise come to mind. There is at least one scene (and maybe more, I can't quite recall now), in which the characters are sitting around in a kitchen and no one is speaking. Jarmusch lets that scene go so long in silence, just ending it before it loses all tension. It's pretty fascinating and I always compare it with the way as kids we would take our chewed gum and try to stretch it as far as we could before it broke into a whispy string. The other scene that I think about all of the time is when the three characters are driving to Florida in the middle of the night. The young woman keeps playing Screamin' Jay Hawkins' version of "I Put a Spell on You" the whole time. It's night and they're driving and listening and saying very little—and the song keeps starting over and over again. I think it's a place and moment that I want to stay in. Who cares about arriving? Stay in the car with Screamin' Jay and the open road at night and all possibilities before you.

BR: Nice.

LG: Anyway, I began simply writing poems with a number attached to the title "Crush," so, like "Crush Number 137." This was influenced by a brief connection with a former classmate of mine, who wrote "First Love" poems that were numbered. I thought that was so clever (thanks, Nicole!), and decided to steal that format and see where it took me.

BR: I love the crush figure, all the ways you fold and re-fold it, all the meaning you squeeze from it, never forgetting the desire angle, the original inspiration.

LG (tasting the squid, which is divine, lubricious and salty and heavy on the garlic): Yes, well that re-folding and folding business was tricky and I think one of the reasons the book seemed to take a long time. I needed room to breathe between writing sections or movements of it. I mean it's desire and it's destruction! What more is there to say?

BR: (long pause over the wine) Could you say more?

LG: Real funny, Roorbach.

(The young guys down the beach stop playing for a moment and start to laugh.)

BR: But I'm serious.

Lea on Martha's Vineyard with Friends (photo Stephen DiRado)

LG: Hm. The nice thing about hitting the very predictable walls that you might imagine, is that I quickly tired of mining my own experience and what seemed foundational texts (The Meaning of Aphrodite and Sappho, for instance) and started to get crazier. Everything became fair game: Big Punisher; Childe Hassam's painting "Big Ben"; Bywater's disease; the Hundred Years' War; Swahili phrases; The Craft of Research; the final blog entry of the poet Reginald Shepherd; etc. Even when I "cannibalized my own experience," as Phil Levine has called it, I pulled in pre-teen girls talking Smallville with sea turtles on a Costa Rican beach. I wanted to see how many diverse and divergent materials I could get into the poems and how far I could stretch notions of desire/destruction—again, like that piece of chewing gum—before they would break. I wanted to give body to crush.

BR: And you have succeeded.

LG: Thank you.

(They eat as the music down the beach starts up again. There's a small crowd of teenagers hanging around, smoking cigarettes, drinking beers. The sun is falling. It's easy to imagine the Phoenician sailors gliding into this bay…. The wine pulls it all into the clearest possible focus, a kind of lens.)

BR: It's clear from the poems that you are an eclectic reader and a collector of phrases and words and objects and people—what's your method for gathering all this material? And how does it make the leap from experience to poetry?

LG: I often think about the experience of reading as personal or lived experience. Perhaps it's not the same overwhelming sensory event as running away from a wild elephant under a full moon in Tsavo East at midnight, but it is still an experience that stays with me as I think it does for most writers. It's hard to say exactly about how I go about collecting, but I like to let my curiosity guide me from one text to another. With that said, I also have an organized reading list when I'm working on a project.

BR: I remember that elephant story.

LG: I told you that one, huh? Ah…I thought I had saved it! Well, then you'll remember that the moon caught the elephant's tusks and glowed. If I hadn't been with two of my friends (who don't write fictional texts), I would have doubted myself on that detail.

LG: I told you that one, huh? Ah…I thought I had saved it! Well, then you'll remember that the moon caught the elephant's tusks and glowed. If I hadn't been with two of my friends (who don't write fictional texts), I would have doubted myself on that detail.

BR: Let me read you one of your poems, "A Crush before the Sexual Revolution."

LG: No, I'll just say it:

Now that I'm old this cold freezes the quarter notes of my thought.

Memory's just a jacklight of once. I used to hide wings & eggs,

damaged things, in a crawl space beneath the house. Colors lived in my eyes

as rejection. I stowed a pocket watch & buckeyes beneath

a sycamore, the clouds of Worcester. My favorite word:

mercurial. I've been summoned through Pig Alley, scanned lavender

fields on the Isle of Wight. I spied a neighbor girl peeing

a ditch when I was ten. Her skirt's hitch & crooked mouth survive.

It's like a hummingbird's quicksilver jab to a red vest.

These are bones in my soup, nevertheless. My father danced

a gimpy box step. My mother stole apples from Kunitz's

tree. One May, I photographed Priscilla in gingham & pearls.

She sang "sugar, cause sugar never was so sweet." At the edge

of Bell Pond. At the edge of Bell Pond. Later that summer she

beaded her thighs with my initials. She carved them there.

BR: I hear music here.

LG: Thanks. That poem took years to write because I kept trying to avoid the speaker, but once I could hear the voice, it fell into place. You know, I grew up memorizing Bible verses from the King James and also listening to Southern preachers. That's the genesis of the music, I suppose. I almost don't like to talk about this because I sound like a walking Southern cliché. I might throw that back at you…. How do you, a guy who "used to play in bands," incorporate music into the writing?

BR: It's in the sentences. It's a rhythm. I don't actually do it on purpose—but when I'm reading aloud, reading to an audience, I'll often realize I'm tapping my foot. I always loved those beat recordings of

Lea Galapagos

, like, Gregory Corso reading with a bongo player and a saxophone. Though I'm no beat poet. There's another music, too, when things are going right, something big humming, almost groaning, that thing I used to hear lying in bed as a kid and thought was the world turning.

LG: Wow…the "world turning." When I was really young my mom always had us taking naps. I was always fascinated with the sound of my heartbeat which seemed to be coming from my ears. I imagined there was a hammer inside of me. So yes…the "world turning" is right on and lovely—and quite a bit more romantic than my hammer!

BR: Hammers have their place. Can you say "Crushed Psalms"?

LG: "Crushed Psalms."

Oh… you want a recitation? Ok, here goes….

Let us gown the red shower curtain

Let us eight track the gospel

Let us double modal & apocopate

Let us tump & perfoliate

Let us call the hogs to scattered examples of fair dialect

As cowbrute so whickerbill

As winter water so skillet tea

Let us climb the tower for a dime & pie

Let us fry the grindle, pickle the gar

Let bone from water & roads of cullet

Let three deep & no lack of corky protrusion

Let K-Tel present the Everley Brothers

Let us "Dream, Dream, Dream"

Let Pistol Gunn come to town,

his Dentyne & gold incisor, his white patent leather.

Let not the girdle nor the mouth of soap

Let us praise Tang & curlers at noon

Let us gin our Dixies

Let us cuss from innocence

As we hymn so shall we holler

As we panicle so shall we spike

Let us impeach our mouths

Let the long "S" of her hair

Let stickers bush & ass pie

May she pull up in her mama's Impala, smoking Camels

May we be thirteen, an empty house

Let us eulogize the candy bars of Piggly Wiggly

Let us sit under the toothache tree with the prom king of poetry

Let "Arkansas Snap"

Let that dog hunt

Let us decoupage Jesus at the door

Let us to the five points of Calvinism

Let not the heat, but humidity's sweet flank

Let Frank Stanford's eyes "shine for twenty dollar shoes…like possum brains on the good road"

Let finger bones of Pea Ridge trumpet honeysuckle

Let the Hard-shelled Baptists we've loved before

Let us belly bob wire, escape by hoopsnake

May there be a bed of devil's food & Seven-up cake

May we kick the can of death

May we walk perimeters of a dare

May this geography guard our going out & our coming in

May all our days reckon & give ear

May the dogwood in April forever, amen

BR: Tump and Perfoliate?!

Lea Guernica

LG: Well, "tump" is one of my all-time favorite words! The reason is that it is a word from my childhood, and if my uncle Jim Pat is to be believed (and I think he's the one who told me this), it is indigenous to the NW Arkansas/SE Oklahoma region. It is a combination of "tip" and "bump." We used it especially when we would turn a rowboat over to drain the water out: "Just tump it." I love the physical sense of the word both in meaning and sound—and that it's a part of the place where I grew up.

BR (Drinking as the sun hits the horizon): Tump, everyone. (The growing crowd of teenagers insouciant in their skinny jeans and t-shirts begin to dance near a fire that we've just noticed. Vendors with baskets stroll at day's end trying to sell the last of their figs, popcorn, cold beers—one of them even carries a giant chocolate Jesus.) Perfoliate!

LG: Yes, it's the way the stem passes through the leaves on certain plants—like a honeysuckle. I love the botany words. Also, remember that most of my family members work in medicine or as scientists and almost all of my grandparents were farmers so, perhaps, that love of language from the natural world is inherited in some ways.

BR: Michael Anania has been a mentor and inspiration….

LG: Well, Michael Anania has been a great teacher and mentor to many poets. I count him and his wife, Joanne, as dear friends. I think there are two particular things that I feel very fortunate about in working with him. First, he has always been a teacher that encouraged a great range of writers and writing. He gave many of us permissions to do what we were doing, rather than turn ourselves into whatever the poet du jour was—or to emulate him and the type of work he does. Secondly, he and I share a serious interest in place. He really helped me to explore the stratigraphical layers of my places—and validated those places that I thought might not belong in poems. He and I always talk about the avocado seed that is suspended in water in an old jar on the windowsill of farm kitchens.

BR: There's one on my kitchen windowsill right now!

LG: Anyway, he gave me permission to value those early images and my own mythology. Also, reading and teaching his work keeps giving. I have been teaching his poem, "Steal Away," this week. It's focused on the neighborhood in Chicago where Chess Records was located and where so many Blues men and jazzmen played and died. The layers of that poem with its "coils and rails" of Chicago's El, the movement and heft of memory and proper names, the suggestion of narratives like the remnants of the plastered Superfly poster is simply marvelous. Michael was a great teacher for me, and is now a friend and has always been a poet I admire and teach.

BR: Literary careers fascinate me. Yours is a work in progress, of course, but with this book I see such an impressive leap. I read many of these poems in draft and loved them, but here, you've revised and re-imagined and re-folded them so beautifully it's as if a new angel had begun to sing to you.

Lea with travel pal Jen in Sevilla, Espana

LG: Well, I wish I had a groovy reason for this leap, as you put it, but I think it is pretty simple. I believe there were two things that helped significantly. First, the time it took to finish the book was a good thing. I know I've been criticized by fellow writers for taking too long with this first book, and I have been self-critical in the past about it, too, but now I'm really glad that it took as long as it did. I got to add and subtract in the last two years before it came out in a way I'm really proud of. That helped me to springboard out from the earlier Anne Carson (et al) materials and get looser (even though the book has been called a "relentless kneading"!) Secondly, I give credit to my editor, Jill Alexander Essbaum. She helped me to see what I was doing (or overdoing, at times) more clearly. I will say that after having spent so many years into workshop, I wouldn't have thought that a good editor could make so much difference, but, at least with Jill, it did. I know as writers we're supposed to be sure of ourselves and even arrogant about what we're doing. I would say that I am those things (hopefully, in a charming way), but I have seen how another pair of well-trained eyes can help immensely.

BR: I adore my editors. Unless I hate them. How has the academic thing fit in? The need to make money?

LG: I get asked this question a lot by my students and I always worry a little because my answer— the path that I took post-undergrad years—might not be very helpful to those trying to figure out how to work as a writer and/or a college professor now. I think the world and the feel of the academy have changed rather dramatically in the last ten years (but this might also have to do with where I'm at in my own life…or maybe both?). Also, I know that a lot of young people starting out are worried about what their families require of them. For this reason, I think my path isn't such a comforting one. In any case, I worked a lot of different jobs in my 20s before I began graduate school. I was a political advocate for a few non-profits working on Central American issues—namely El Salvador and Guatemala. I worked  briefly in a homeless shelter and in inner-city youth centers. I did all kinds of temp jobs. Even when I went to grad school, I was still waitressing and bartending along with my teaching assistantship. So I worked solidly for six years before graduate school and then another six or seven during graduate school at other jobs besides those in academia. Once I finished my Ph.D., I taught as an adjunct at three other institutions along with the Clemente Course for the Humanities through Bard College for another five years before I was hired as a tenure-tracked professor. There's so much luck involved with teaching careers—even with hard work. I will say that while this path was certainly a sweaty one, in many ways, I wouldn't trade it because of the range of experiences it has given me.

briefly in a homeless shelter and in inner-city youth centers. I did all kinds of temp jobs. Even when I went to grad school, I was still waitressing and bartending along with my teaching assistantship. So I worked solidly for six years before graduate school and then another six or seven during graduate school at other jobs besides those in academia. Once I finished my Ph.D., I taught as an adjunct at three other institutions along with the Clemente Course for the Humanities through Bard College for another five years before I was hired as a tenure-tracked professor. There's so much luck involved with teaching careers—even with hard work. I will say that while this path was certainly a sweaty one, in many ways, I wouldn't trade it because of the range of experiences it has given me.

BR: Including the hard knocks.

LG: I guess what I'll also say to those who want to be writers: You can write while you work at almost anything. I don't think that I necessarily have more time to write now that I have a full-time job in academia. The time to prepare for and teach classes, run academic programs, and to work in a department and for an institution is busier than it appears. (Actually, I blame my own undergrad profs for making this profession seem so effortless. We laugh about that now!) To pass on the great advice that Sherod Santos gave me years ago: If poetry (or writing in general) is important to you, you'll get back to it. I would add to that and say that you don't have to "go away" from writing. You can keep doing it no matter what your monied work is. It's fun to get to teach writing on a daily basis, but that doesn't necessarily legitimize me as a writer. I know some of my poet colleagues would say that it probably makes me more boring! I would encourage writers to slow down and figure out how to keep writing (and reading) alongside whatever they do to earn their physical sustenance. Don't worry so much about rushing to publication or immediately entering MFA or PhD programs in writing. Those things are great, but I think that to be a really solid and thoughtful artist, it's necessary to work at your craft apart from, or at least not driven by "credentials." I know that this is counter to everything we hear and feel in a society that values immediacy and that asks for more and more accreditation. I know that I struggle to work out that balance between making my art public and working steadily, healthfully, and satisfyingly in private— towards my own standards.

[image error]

With novelist Baker Lawley in front of the Met, NYC

BR (Slowly, and watching the ocean as Lea opens a second bottle of the wine): Speaking of standards, a favorite poem of mine is "Bridge Jumping/ W4M / Poughkeepsie (The Walkway)." Can you say something about the prose poem in general, and about this poem in particular?

LG: Funny you should ask about that since I'm in the process of writing a whole lot more prose (or prosier) poems for this next book. I like the no fuss no muss of the prose poem. It feels to me like you can pack it with "stuff"—like an ungainly suitcase with all your favorite things. You don't have to worry so much what it looks like. I am also finding it to be well suited to the epistolary poem, as I'm working on a series of them right now. With that said, I think it's easy to commit errors that you might not if you were more attentive to line breaks. I always try to air out my prose poems to see if that's what I really want as a form and to see if there is content that shouldn't be there. "Bridge Jumping…" was an assignment given by Brett Fletcher Laurer, a poet who runs a blog called Ships that Pass. It's a blog that runs "fake missed connections"—the kind that you can read on Craig's List. I had to go and read a lot of these, along with the other poets' fake versions, to get a sense of how it worked, but it was a blast! It is a write-in on Craig's List where you can address someone you have seen in passing and thought you had a connection with. I thought it was perfect for the crushes because it is the briefest of sightings. Still, enough energy and imagination was there to make you want to write the person.

BR: They used to have ads like that on the back page of the Village Voice: "You: Brown sweater and big eyebrows on the A Train to Canarsie. Me: Reading Dharma Bums and crying. You said, I could love a man like you." Do the line lengths of a prose poem matter as they appear in the book? Or does the poem work as prose works, fitting the page on the page's terms?

LG: If I remember correctly, this poem mostly broke where it broke (although there was a lot of taking out/putting back in and all of the usual work that revision is). There were other poems in which the page was a hindrance. I had to re-break lines to make them shorter since the page wasn't wide enough for them. It was a strange experience having a page push me and my choices around. It was the difference between individual poem writing and book making, I suppose. I'm wondering if you as a prose writer have to think about the spatial/structural parameters as you write an individual story or essay, and then again, when you write or put together a book?

BR: Definitely, but not in such minute matters as line breaks. More in where recreated documents are placed and broken, or where a chapter breaks. You want all the chapters to open on a right-hand page, for example. Can you say the poem?

LG: "Bridge Jumping…"

You smelled of burning maps, smirked as to let slip the dogs of war. Not the stale slate windbreaker & steel-cut oats above the Hudson. I was whistling "Wake Up, Little Susie" & wearing a huipil. Your crow's feet, tasseographical signs for journey of hindrance, diploma . The conversation went like giraffes fighting: How do you behead a poem like a horse? Why is the "ch" silent in "chthonic"? I refused your urge to push the mental health button, see what might appear: pair of falcons, oil cymes between trains, a child in a tiara. I told you the death rate was 1180 for every 1200 jumps, including Kid Courage. I told you in Hong Kong it's the most popular form. You said falling from this height blows your clothes off, denies the senses. You wondered what happened to the 20 who got away? Cross-winds, a unicycle & my Mets cap divided factors. But I keep thinking of you like Colomb & Williams thought of Wayne C. Booth, writing his voice into the third edition of The Craft of Research years after he died. I imagine you might fish endangered sturgeon & dream of Guernica on Thursdays. If so, write to me. We could go to sea in a sieve, double the blind, buck your tiger, bell my cat, leap this dark—

You smelled of burning maps, smirked as to let slip the dogs of war. Not the stale slate windbreaker & steel-cut oats above the Hudson. I was whistling "Wake Up, Little Susie" & wearing a huipil. Your crow's feet, tasseographical signs for journey of hindrance, diploma . The conversation went like giraffes fighting: How do you behead a poem like a horse? Why is the "ch" silent in "chthonic"? I refused your urge to push the mental health button, see what might appear: pair of falcons, oil cymes between trains, a child in a tiara. I told you the death rate was 1180 for every 1200 jumps, including Kid Courage. I told you in Hong Kong it's the most popular form. You said falling from this height blows your clothes off, denies the senses. You wondered what happened to the 20 who got away? Cross-winds, a unicycle & my Mets cap divided factors. But I keep thinking of you like Colomb & Williams thought of Wayne C. Booth, writing his voice into the third edition of The Craft of Research years after he died. I imagine you might fish endangered sturgeon & dream of Guernica on Thursdays. If so, write to me. We could go to sea in a sieve, double the blind, buck your tiger, bell my cat, leap this dark—BR: Do you mind teasing out the references here, or is that too much to ask?

LG: It's my pleasure. Actually, one of the things that simultaneously flatters and irritates me is that some audiences have thought this was an actual experience. As I said, it was an assignment. What is actual is that I live near and walk on the Mid-Hudson Pedestrian Bridge pretty often. So I'm always looking at the different details of the bridge and the water. I ended up doing a lot of reading about suicide by jumping because I had seen the mental health button on that bridge. I kept thinking about how jumping from such a height would impact a person. (So is it a romantic crush or a destructive crush?) I learned all sorts of things, but maybe the most interesting information made it into the poem? In any case, I wanted to see how many different kinds of materials I could get into the poem…so I use a line from Julius Ceasar and reference a "huipil," the Mayan smock-blouse that is heavily embroidered and usually, quite bright, and which has both cultural and political value in Guatemala. I don't know… I was just having fun with the Everly Brothers and The Craft of Research and whatever else I was reading at the time or could think of. I like the circus of the poem. In fact, that aspect for me is the poem—not the "missed connection." That's probably disappointing because everyone wants a little gossip or a little romance, but it just ain't happenin' in this poem beyond the assignment. Although, I hope it gets people to write their own missed connections!

(A camel train is trundling down the beach, men with long sabers and longer mustaches at its head, hundreds of animals, jingling bells, the cries of drovers, belly dancers on elephants)

BR: My ride is here.

LG: Well, it's been very nice talking.

BR: May I take the rest of this bottle of wine?

LG: There's but a sip. (she pours what's left into our two glasses, and we toast, throw back the last drops.)

BR (climbing onto the back of a elephant with the help of the camel drovers, who are impatient. He shouts): Could you leave me with a poem?

LG (declaiming as the young guitarists come to stand around her, gentle strains at sunset):

"Crush Starting with a Line by Jack Gilbert

Desire perishes because it tries to be love

& so, I think, why search or seek it? Entering

its way out the backdoor, calling as Narcissus

himself, curious to himself only—only

this echo. Yet, some days wild turkeys wing clumsy

across windshields, or poets come to town

& language flocks before flying south, before

jubilee, before hush & slack. In chance,

what we flush from beech & oak, or her flush blooming

at a table, remains, persists as flight, or flown:

trace of bird in my eye, balloon drift among sky,

proposing hand, arm. What is not sexual, though

sex is part, catches life en theos. Not love, but its

roaming kin & nonetheless, wonderful alone.

Classic Bill: "Into Woods"

Dave and Poppy, October 12, 2011

Gardening one day in the spring of 1992, first year in Maine, I looked at my dirty and freshly blistered hands, and thought of my days in construction. Idea for an essay. I wrote the words "my hands" on a seed packet and the packet went into the ideas folder. Another idea I'd had was to devote Saturday mornings not to the novel I was working on (eventually to be The Smallest Color) but to shorter work. I went into the ideas file–a bunch of paper scraps and napkins and coasters and pulled out that seed packet. The piece didn't start out being about my father and me, but.

(The photo at left is from Dave's recent reading at the Carter Center in Atlanta. And my dad, 85, got in the car and drove over to see what was what. "I can see why you two are friends," he said on the phone. You can see more of Poppy in Chapter 5 of "I Used to Play in Bands." He's a pretty funny old bird.)

"Into Woods" was first published in April of 1993 by Harper's Magazine, where I'd go on to publish a number of other pieces. My editor there was Colin Harrison, a smart guy, now a friend (and a senior editor at Scribner), who had to that time rejected a long parade of my stories and essays, sometimes with encouraging notes, but not always. He read the original draft I'd submitted of "Into Woods" (the working title was "Woods II") and made up his mind to argue for it to his colleagues. Fortunately for me, he prevailed. He phoned, then, and said, "We're going to publish your piece."

I tried to sound cool: "Wow."

"One thing," said Colin. "You have to finish it." He gave me nothing more than that to go on, only this: a deadline, one month hence.

And I sat down with the piece I'd thought quite finished and puzzled and groaned and read and tore my hair and re-read till in the middle of a deep, tossing night, one week to go, I had an idea: My dad had just visited my new house in Maine, and we'd just rebuilt the garage. Though the material was fresh—only a couple of months past—it turned out to be what I needed to bring the story full circle.

Thanks, Colin. Thanks, Pop.

#

INTO WOODS

In a dive near Stockbridge in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts, I nearly got clobbered by a big drunk who thought he'd detected an office fairy in the midst of the wild workingman's bar. He'd heard me talking to Mary Ann, the bartender, and I didn't talk right, so by way of a joke he said loudly to himself and to a pal and to the bar in general, "Who's this little fox? From Tanglewood or something?"

I, too, was drunk and said, "I am a plumber, more or less." I was thirty years old, was neither little nor a fox, had just come to work on the restoration of an inn, and was the foreman of the crew. But that seemed like the wrong answer, and too long in any case.

He snorted and said to everyone, "A more or less plumber," then appraised me further: "I say a hairdresser."

"I say a bank teller," his pal said.

I didn't mind being called a hairdresser, but a bank teller! Oh, I was drunk and so continued the conversation, smiling just enough to take the edge off: "Ah, fuck off."

"Cursing!" my tormentor cried, making fun of me. "Do they let you say swears at the girls' school?"

"Headmaster," someone said, nodding.

"French teacher," someone else.

"Guys . . . ," Mary Ann said, smelling a rumble.

"Plumber," I said.

"More or less," someone added.

"How'd you get your hands so clean?" my tormentor said.

"Lily water," someone said, coining a phrase.

My hands? They hadn't looked at my hands! I was very drunk, come to think of it, and so took it all good-naturedly, just riding the wave of conversation, knowing I wouldn't get punched out if I played it right, friendly and sardonic and nasty all at once. "My hands?"

My chief interlocutor showed me his palms, right in my face. "Work," he said, meaning that's where all the calluses and blackened creases and bent fingers and scars and scabs and cracks and general blackness and grime had come from.

I flipped my palms up too. He took my hands like a palm reader might, like your date in seventh grade might, almost tenderly, and looked closely: calluses and scabs and scars and darkened creases and an uncleanable blackness and grime. Nothing to rival his, but real.

"Hey," he said. "Buy you a beer?"

#

My dad worked for Mobil Oil, took the train into New York every day early-early, before we five kids were up, got home at six-thirty every evening. We had dinner with him, then maybe some roughhousing before he went to bed at eight-thirty. Most Saturdays, and most Sundays after church, he worked around the house, and I mean he worked.

And the way to be with him if you wanted to be with him at all was to work beside him. He would put on a flannel shirt and old pants, and we'd paint the house or clean the gutters or mow the lawn or build a new walk or cut trees or turn the garden under or rake the leaves or construct a cold frame or make shelves or shovel snow or wash the driveway (we washed the fucking driveway!) or make a new bedroom or build a stone wall or install dimmers for the den lights or move the oil tank for no good reason or wire a 220 plug for the new dryer or put a sink in the basement for Mom or make picture frames or . . . Jesus, you name it.

And my playtime was an imitation of that work. I loved tree forts, had about six around our two acres in Connecticut, one of them a major one, a two-story eyesore on the hill behind the house, built in three trees, triangular in all aspects. (When all her kids were long gone, spread all over the country, my mother had a chainsaw guy cut the whole mess down, trees and all.) I built cities in the sandbox, beautiful cities with sewers and churches and schools and houses and citizens and soldiers and war! And floods! And attacks by giants! I had a toolbox, too, a little red thing with kid-sized tools.

And in one of the eight or nine toolboxes I now affect there is a stubby green screwdriver that I remember clearly as being from that first red toolbox. And a miniature hacksaw (extremely handy) with "Billy" scratched on the handle, something I'd forgotten until one of my helpers on the Berkshires restoration pointed it out one day, having borrowed the little thing to reach into an impossible space in one of the eaves. Billy. Lily.

My father called me Willy when we worked, and at no other time. His hands were big and rough and wide, blue with bulgy veins. He could have been a workman easy if he wanted, and I knew it and told my friends so.

#