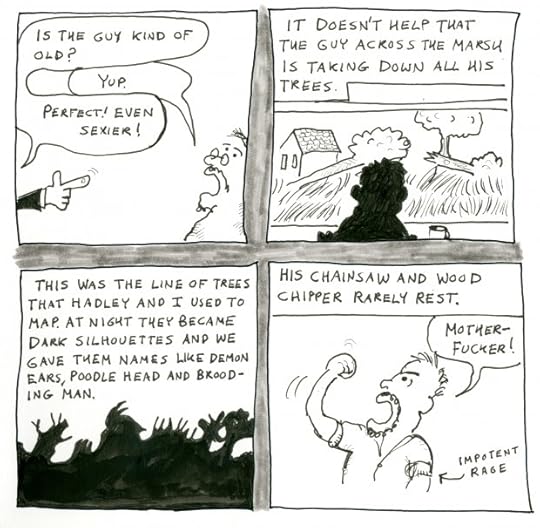

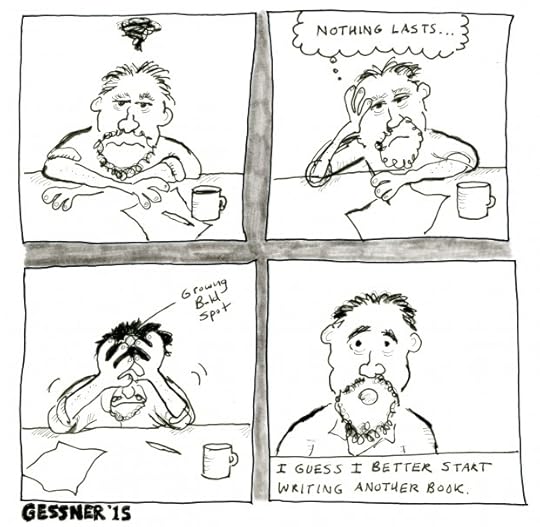

David Gessner's Blog, page 14

September 13, 2015

The Last September

Nina de Gramont’s novel The Last September is due out next week. It has gotten some great early reviews and here’s the latest, a starred review from Library Journal:

Nina de Gramont’s novel The Last September is due out next week. It has gotten some great early reviews and here’s the latest, a starred review from Library Journal:

“In her latest stunning novel, de Gramont (Gossip of the Starlings) wastes no time. Brett Mercier, a brilliant academic specializing in Emily Dickinson, is a young widow with a 15-month-old daughter. Her husband, Charlie Moss, has been murdered on Cape Cod. The likely suspect is Charlie’s younger brother, Eli, who was Brett’s best friend in college before he was all but lost to the ravages of schizophrenia. From Brett’s love-at-first-sight teen crush on girl-magnet Charlie through the heartbreak of his years-long elusiveness to her brief engagement to safe, wealthy Ladd Williams, whose family is tied to that of the Moss brothers on the Cape, to Charlie’s murder, the mystery unfolds with unexpected detours. The torture of unanswered questions resulting from violent death is on full powerful display, as are Brett’s torn loyalties—to the terribly ill Eli, to the devoted fiancé she spurned, to her irresistible, unfaithful late husband—that threaten her stability. VERDICT With an artist’s eye and a poet’s heart, de Gramont realizes a world of love, mystery, and the shattering sorrow of mental illness, deceit, hope, and lives cut short. Impossible to put down.”

Makes you kind of want to order it, right?

September 9, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: One Sentence on Getting Back to Work, September Style

Like Daughter Like Father

I still get that September back-to-school feeling about now, even though I’m not teaching anymore, that feeling of gearing up, getting ready, pencil boxes and notebooks and ink for the fountain pen (I started grade school in 1958), a dog to walk you to school Norman Rockwell style, maybe even a lamb, as in Mary had a Little, all with a stout resignation—summer might not be over, but the time to work is here, the time to stack projects like cordwood, the time to make those calls, finish that book, wake the slumbering beasts, polish an apple or two, look out for the red-haired girl, be a writer at the desk and not so much a writer at the beach, a writer who’s gonna get it done, and get it done, and get it done, then ask for more.

Bill Roorbach is Bill. His novel Life Among Giants is a fall book, with nearly every scene taking place during the season of declining day length…

September 8, 2015

September 7, 2015

Letting the Delta Die to Save It

IDL TIFF file

By Guest Poster Jimmy Guignard (Cartoon head coming…)

When Katrina hit the coast in 2005, I was in Pennsylvania packing up to head to North Carolina for a short visit before the semester got away from me. The phone rang. My brother, Billy, said, “Hey, man, you don’t want to come down here. We’ve got no gas.” Holy shit, I remember thinking. I had been following Katrina a little—I hadn’t lived on a coast in years, so I no longer tracked storms for their surfing potential. But my brother’s warning pushed me to read obsessively about the hurricane’s impact. Horrifying.

This is the 10 year anniversary of Katrina, and not surprisingly, the storm and its aftermath have been prominent in the news. President Obama made a trip to New Orleans to say that we’ve made progress though we have work to do and Michael “Heckuva Job, Brownie” Brown explained why nothing was his fault.

In 2012, I read Dave’s Tarball Chronicles and began to understand the nature of the Delta. Now, though I write about fracking in Pennsylvania (another kind of disaster), I keep an eye on the Gulf. One theme I encounter often: rehabilitate the delta. Writing in Scientific American, Mark Fishetti reports that teams are creating plans to do just that—by letting the southernmost part of it die.

Fischetti tells the story of the Changing Course Design Competition, a competition that asks teams of experts to imagine ways to make the delta more sustainable and let it do its work of protecting the coast. According to Fischetti (and nearly everyone else, it seems), the biggest problem with the Delta is that it’s not being allowed to replenish itself, which means it’s losing its storm-absorbing properties. Put another way, the levees that control the floods starve the marshes of the much-needed sediment and nutrients carried there by freshwater.

Fischetti’s article is worth a read. So is this companion piece of sorts by Politico’s Michael Grunwald about the Army Corps of Engineers’ contribution to the mess. What grabs me most—and something I see here in the frack zone—is the way what I’d call Big Idea Planning trumps local knowledge. I want to see more small idea planning, planning that includes curves, nutrients and sediment, the mixing of salt and fresh water, the gradual accumulation of local knowledge. Changing Course says it all, right?

September 3, 2015

Guy at the Bar: Vince Passaro on Harold Brodkey, Gordon Lish, and Pat Towers, Middle of the Night

Lish

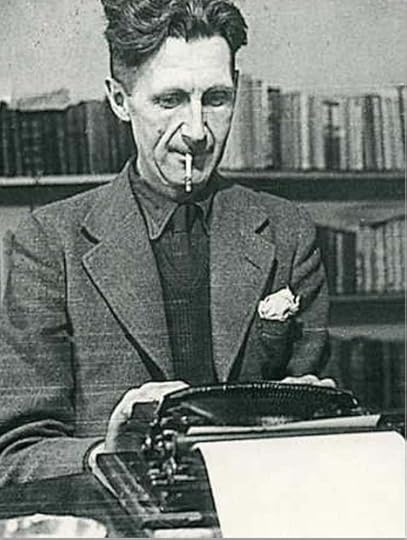

Up tonight, knee shaking, foot shaking. I think Trader Joe spiked my decaf. So it’s 1:00 a.m. when I start thinking about Harold Brodkey — does anyone think about Harold Brodkey anymore? All artistic talent of the first order is incomprehensible but certain talents strike us as more familiar and approachable than others. George Orwell, for instance, whose prose’s muscle and clarity — clarity above all — affected me strongly, does not mystify me. I have a solid sense of where he came from, where his language came from, his general mode of thinking. Brodkey’s particular genius remains ungraspable. The language is Jewish, it’s American, it’s baroque, it’s beautiful and divine. Divine I mean as in suffused with a spiritual force and a spiritual necessity above that mustered by mere mortals. It is miraculous and harrowing: to look into his work is like watching a great surgeon, a world class surgeon, magically operate on himself, remove his own organs, examine them in bloodied hands, drop them in a pan.

The reason I’m thinking of Brodkey is first because of Gordon Lish, whom I have wanted to write more about. I said in an earlier post that I think he is the most influential editor of his time and perhaps the most influential literary figure of his time in the United States. He came into my mind because I could suddenly hear him say Brodkey’s name. Never Harold Brodkey, just Brodkey. As a teacher Lish held Brodkey up always as the pinnacle of what you as a writer could achieve if you stopped fucking around and fooling yourself that what you’re doing now mattered in the least or displayed a shred of real talent… if you essentially got your ass up off the planet and into the heavens where it belongs. Lish reacted to words, to writing, and to writers in an unmistakably erotic way: he was then and I imagine still is a literary creature full of worship and desire. He moved hard toward what he liked, or he moved not at all. He was notoriously heterosexual, at least as far as all the rumors went, and there were many. Yet with certain male writers, as he evoked them, you could hear an erotic love, an erotic pleasure: Brodkey, Hannah, DeLillo. There were many other males writers who, as he worked with them, became part of the incantations: Anderson Farrell and Tom Spanbauer come to mind.

Brodkey

What needs to be looked at, carefully, and I don’t have them and I don’t have the time to go find them and read them, are all the issues of The Quarterly that he published from the mid-80s to… when? The early 90s? The work that I will forever most associate with The Quarterly are the drawings of a particular artist featured in every issue, whose name I cannot remember, and the poetry of Jack Gilbert — Lish’s dedication to publishing Gilbert somehow cements the sense that what he treasures most in literature is the language of revealed secrets. Gilbert’s poems always seem to me to have the effect of a door opening and throwing a lovely golden light into a darkened hallway. Illumination and revelation. Art as a moral act and an erotic act: the connection of one being to another.

But — after all this passes through my mind — I realize why I am actually thinking of Brodkey: because it is PatriciaTowers’s birthday today. She was born on September 3. What year that was is a deep secret, which only the obituary editor at The New York Times might know, and certain agencies of government; putting my hope in the Times I intend to outlive her just so I can find out. She too, like Lish, has been one of the great and important editors of her time: but utterly different. (They are both retired now.) They both want the writer to seduce, but Pat wants to end up in love. It is a sensuous love, certainly: she worked on ideas and on texts somehow in the manner of a Buddhist forever engaged in the arrangement of stones in a Japanese garden. Everything — what was a good word, a good sentence, a good idea for an article at this time in this place — seemed to be decided by feel: a feel informed by sympathies that radiated outward from the stones, ceaselessly radiated, and took in the world and the air in which the stones must rest, all with the aim of making sure that they were properly — elegantly, correctly, beautifully — situated there. Her work was as close as a busy editor’s work can ever be to flawless, something Gordon Lish would never dare claim for himself.

Pat Towers

And her relation to Brodkey? Among other things, my own meager career, such as it’s been. In 1988 she left Vanity Fair, where she’d been one of the founding editors, and done some amazing things unimaginable now, in today’s over-processed publishing landscape (such as, I remember, two simultaneous pieces on Glenn Gould, who had died a year or two prior, one by Tim Page and one by Edward Said, that ran stacked one atop the other splitting the pages they appeared on). She left VF to work on a start up magazine, a New York City magazine, called 7 Days. I had just finished my half-assed MFA thesis in fiction at Columbia, studying under Pat’s husband, the novelist, critic and teacher Robert Towers. He had mentioned me to her as someone who might possibly be able to review a book, and I wrote to her a few months after graduating asking if she had any work. This is the kind of inspired editor Pat always was: she did have a book, she decided, for someone who’d never written for hire or reviewed anything at all: the most long-awaited work of the year, by one of the most controversial writers on the New York scene. She decided I should review Harold Brodkey’s Stories in an Almost Classical Mode, his first book in almost 30 years. My status as neophyte had a certain appeal, she told me: everyone else she could think of already had an opinion about Brodkey. This was, I would come to understand, a loaded remark. His charms, which were considerable, were often overtaken by other more difficult aspects of his personality: he wasn’t merely an acquired taste, he often made himself into a lost taste. As it happened I had met Brodkey, he’d done a four-day Master Class that spring at Columbia, during which he’d looked at me in my plaid shirt and unwashed jeans and ten-year-old hiking boots which — God knows what i was thinking — I had planted up on the conference table, and he said, “You must have a great deal of self-confidence to sit there like that.” I was so naive Ithought it was a compliment.

So sometime before 2 a.m. I go looking for a copy of this, my first non-fiction publication, my review of Brodkey written for Pat, and find many other interesting things in 30 years worth of files, until finally, around 3, in the bottom drawer rear, in the last file, at the back of the file, I find it. It’s not a bad piece, though slightly repetitive; like everything else I write, too long; I tried to do justice to how daring the work is, what a psychological high-wire act Brodkey performed. The parts of him that were overbearing were crucial to his art: his art was overbearing as part of its design. More than any other writer I know of, he wrote in order to be loved, and so as painful as writing is for all of us who do it, it was more painful for him.

After the Brodkey piece ran in the fall of 1988 I went on to write many many pieces under Pat’s guiding hands, each, because of her, a stone of unique shape and color. She will be annoyed, superficially only, I hope, to be written about, but it’s just my as-usual-long-winded way of saying: Happy Birthday, Pat. I’m feeling a little sleepy now….

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen… This piece and a lot of other great writing first appeared on his blog, Bitter Conceits.

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen… This piece and a lot of other great writing first appeared on his blog, Bitter Conceits.

September 2, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Waiting for an Audience

Readers of Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour, I need some bad advice. I have just completed the copyedits for my forthcoming book, which means all that remains will be to check the proofs and create the index. Those are pain-in-the-ass jobs, but don’t require much intellectual or emotional investment. All of the heavy lifting, the drafting and revising and editing, have been completed at this point.

Readers of Bill and Dave’s Cocktail Hour, I need some bad advice. I have just completed the copyedits for my forthcoming book, which means all that remains will be to check the proofs and create the index. Those are pain-in-the-ass jobs, but don’t require much intellectual or emotional investment. All of the heavy lifting, the drafting and revising and editing, have been completed at this point.

So now here I am attempting to launch the new project. In one way of the other, this project will involve a reappraisal and appreciation of the work of one of our most famous writers of the 20th century, George Orwell. I want to rescue him from Animal Farm and 1984 (which is not to say they are not great books, as they are) and help recover the George Orwell that I think really matters to our modern age: the man who worked and lived among the poor, wrote eloquently about the daily humiliations and injustices of poverty, and believed that nature had the power to rescue us from the economic inequality. It’s an Orwell that his most devoted readers will know well, but that the average reader of his work has likely never encountered, or only knows through the descriptions of the proles in 1984 and the working livestock in Animal Farm.

I believe in this project, and I want to write it. I have been reading Orwell’s entire corpus from start to finish (more than 8,000 pages), as well as biographies and criticism, and I believe I can write the hell out of this book. Self-confidence has never been a problem for me.

But I’m paralyzed. The question I can’t seem to answer is this: who is my audience? Am I writing this for my fellow academics, to offer a scholarly analysis of how and why 1984 and Animal Farm supplanted the work that Orwell was known for largely in his lifetime? (This is a fascinating tale which involves, at least partly, an effort by the CIA to promote books that supported American values, including Orwell’s two most famous novels.) Or am I writing for it my fellow readers, to help them recognize that the Orwell they love (or perhaps hate) has so much more to say to them than “Big Brother is Watching You!” and “Four legs good, two legs bad!” A book along these lines would fall into a genre that has been ably populated by many other writers, including none other than this site’s own David Gessner, in All the Wild That Remains, or Andrew Kaufman in Give War and Peace A Chance. This version of the book will begin with my re-discovery of Orwell’s work in a Paris bookshop, a writ-small version of the eye-opening experience I hope to give to readers.

When I was first learning to write and submit my work for publication, I recognized quickly that the fastest route to seeing your work in print was to familiarize yourself with a magazine or newspaper, and then write an article specifically tailored to its audience. I do this all the time now; I never write an essay unless I know the publication to which I will be submitting it at the very start of the process. I learned this again with the publication of my first books: you had to identify your potential audience very specifically if you wanted a publisher to take a chance on you.

So a part of me wants to be very clear with myself about my audience before I draft a single word. And yet another part of me thinks I will figure out my audience as I write. (That part of me, however, isn’t thinking about how frustrating it will be when I figure it out halfway through and have to start again from scratch.) I had hopes that writing about this dilemma in my journal would help me tap into my inner muse and sort it out, but after many dozens of journal entries focused on the same question I have determined that my inner muse is an idiot.

And so, dear readers, your bad advice please. Plunge ahead without really knowing my audience, or continue to sit here and dither until I figure it out? Or—and I hope there is an “or”—some third alternative? What am I missing here? Do you have your audience locked in before your begin a book project? Or do you let things flow for a while and see what happens?

Jim Lang is the author of Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty (Harvard UP, 2013). Visit him at http://www.jamesmlang.com or @LangOnCourse.

September 1, 2015

Anxious Bode Goes Electric!

Thierry Kauffmann, aka Anxious Bode

Hi, this is me, Anxious Bode. I told you about my battle with Parkinson’s. I told you about my concerto, too. The one I’m writing based on an improvised piano piece. I was going to behave, orchestrate it the standard way, with cellos and brass. But I was aiming too low. Not revolutionary enough. You know how I know that? When I aim low my health goes down. And it did. So I had to think of something big, outside the box. If you had to name one instrument that is guaranteed not to work well with with piano, it’s electric guitar. Chopin with electric guitar, you get the picture. And yet.

I know I dreamed of being a rock musician. I also loved classical music but most classical music is dead. Great for films, for journey, but when it comes to actual walking, it fails. Put Rachmaninoff in a disco people start crying. Classical music can move the soul, but the body needs something more earthy, closer to the ground.

It all started with an email. Someone, somewhere, had heard my music. My old piano music, Wish You Were Here, the one I had written for a dance class, modern dance, those were days of bliss. He offered to transcribe my music, write all the notes, so other pianists could play it. That had me jumping up and down. I heard telescoping orchestra sounds, Carnegie Hall, Grammy and back. After the crash of my orchestral dream,and health, I started to think. What was so irresistible in this old piece was not the music, it was the dance, the dance that gave birth to it. And that dance had been able to move an entire dance class only after I had let go of all classical piano. What remained was a mix between alternative rock, and Bach.

This old piece was my testament at the time. I had hit a wall, had to get a job and lay piano dormant for a while. So this resurrection sent a shockwave through me, after which I declared myself healed. I also started to lose sleep, wondering what to make with this new alchemy of sound. There was one way to find out, it was to play. Improvise my way through the concerto.

I’m sitting at my desk, I got my keyboard, small, three octaves, plugged into my phone. Inside my phone is a program, a virtual instrument, an Arp guitar. Out of two speakers comes the sound of the piano. I have placed the guitar aka the phone and the speakers as on a miniature stage. The whole band, is recorded by a recorder also expertly placed, to reproduce what I would hear from an actual band. Toward the end of the piece, the piano rises. I listen to the band with headset and I hear the guitar burn its way through the rousing piano, tearing away like lighting the pregnant sky and inscribing my will to live with letters the size of New York Harbor.

P.S: You can hear the result here. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_qnUdxW3e2k

August 31, 2015

August 29, 2015

Guy at the Bar: AWP and Diversity. Does No One Out There Have Any Sense?

Bill and Dave at AWP Boston

AWP — who gives a fuck? (There’s a little so-med shitstorm about Kate Gale’s not altogether sensitive piece in The Huffington Puffington I’llBlowYourHouseDownington Post about AWP “diversity” — about which I guess I give enough of a fuck to write this.) Here’s some news: AWP–the Association of Writing Programs–is an association of MFA programs. It looks like an MFA program, it walks like an MFA program, it talks like an MFA program, what’s the issue here? It’s bureaucratic and uninteresting and being twice removed from the actual task and demand of creative writing, it is in every way an “organization”, handing out tote bags and missing the point. In any case, further news for the uninitiated: MFA programs charge a lot of money and keep two thousand writers employed with 403Bs and good medical plans and good cars and nice refrigerators. (As the familiarly-initialed WPA briefly tried to do, but way less intrusively.) In all but a handful of cases the programs are designed as not-great-but-steady profit centers for universities who have to spend money on students in other (liberal arts, non-professional) programs. Therefore students face high tuition costs. So what do people expect its representative organization to look like? A social services agency? Many MFA students are cash poor and go into hock up to their necks to study writing with teachers and fellow students whom they admire and hope to be enlightened by; I did this once, though it wasn’t so expensive then. (That’s how I met Bill Roorbach!) But if you come from a place that is poor, if everything and everyone you’ve ever known is poor, it takes a particularly rare kind of cognitive and cultural leap to go $20-40,000 in debt, or more, to get into a profession that doesn’t pay and never will. As such a poor person, you would have had to have done this already for your BA in most cases, so the odds are really low. Does no one out there have any sense? AWP stands for All White People, because as Kate Gale put it, so amusingly cluelessly, that is us.

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen…

Vince Passaro is the author of Violence, Nudity, Adult Content: A Novel (Simon and Schuster, 2002 and S&S Paperbacks, 2003), as well as numerous short stories and essays published over the last 25 years in such magazines and journals as The New York Times Sunday Magazine, The Times (London) Sunday Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, The Nation, The Village Voice, The New York Observer, Esquire, GQ, and Harper’s Magazine, where he is a contributing editor. He’s also the guy sitting alone at the end of the bar, plenty to say to those who will listen…

August 28, 2015

The Four Easy Steps to Becoming a Writer

We are thrilled to announce the publication of old friend Daren Dean’s novel Far Beyond the Pale. It was great years ago when I first read it and I know it’s even greater now. Click here to find out more from Fiction Southeast.

We are thrilled to announce the publication of old friend Daren Dean’s novel Far Beyond the Pale. It was great years ago when I first read it and I know it’s even greater now. Click here to find out more from Fiction Southeast.And Daren was also generous to offer us these tips:

Famous Writers Course: The 4 Easy Steps to Becoming a Writer

“I would advise anyone who aspires to a writing career that before developing his talent he would be wise to develop a thick hide.”

-Harper Lee

So how do you do it? Where do you get your writing ideas from? I would write too if I only had the time. How much money did you make? These are the kinds of questions and comments writers hear all the time. Why won’t writers just answer these simple questions? I have the answer. They are holding out on you. I’m going to tell you the secrets. Let me just tell you the easy way to write novels and get them published. It isn’t that hard really. I will help you with these 4 easy steps:

1) Arrange your life for many years to do the writing life.

What’s the writing life? Well, as far as I can tell it has something to do with writing a lot even when you’re not particularly inspired. What do you do? You push through and you write anyway on a daily basis. Abandon all plans of professional jobs that you might fall back on. Those plans will turn into your reality. Then, you will have a good job you hate, which is fine until your mid-life crisis hits. Besides to a writer trying to make it, just about everyday is a mid-life crisis. Writers dredge up old hurts, sometimes their own and sometimes others, turn them into 3D models and examine them instead of trying to forget them like normal people. You are a writer…now write.

2) Make Time to Write. It sounds like rule #1? Sorry. I just want you to know most of the writing you will get done is through sheer force of will. The muse is closed on Mondays and she doesn’t sell beer on Sunday until after Noon. You can text her if you want but she’s a bit of a Luddite and doesn’t like cell phones and sometimes she waits a week or two before she gets back to you. And that’s if you can figure out what the hell she’s talking about when you do get the message. She’s got fat fingers and autocorrect doesn’t help matters either.

You don’t have time for writing? Well, unless you have some amazing connections then you’re not likely to write much or very well. So this idea that writer time works different from clock time is something maybe only a physicist could really get into that with you. But go back to rule #1 before you ask anymore questions. I wrote the entire rough draft of Far Beyond the Pale from roughly August 2001-January 2002 by writing 6 days a week for about two hours every morning before I went into work. Then, when I was waiting for comments from other writers, I wrote the rough draft of a second novel in about 6 months. People like to throw their slings and arrows at writing programs but it gives you the time to focus on your writing and then it gives you built in readers in the form of other like-minded writers.

3) “You’re a Genius All the Time.”

Does that sound crazy? (I stole it from Kerouac but I’ve always liked it.) Yeah, to me too but writing consistently like I mentioned gave me the momentum to keep writing. Did someone promise me they would publisher either book first? No. The common wisdom would say don’t do it if no one is promising to pay. But for 99.9% of new writers no one will promise you anything. You need tenacity in the face of failure. Any writer with some talent has an inner vision of the world that they draw from. They write “from their continent” as writer Michael Pritchett once said. I say it’s that amorphous convenience store of emotions and memories you’ve got to draw from. What’s your vision? Trust it. Go on instinct. Write and develop your story over time. You might be talented but really it takes guts to keep writing, especially in the face of rejection. Write for yourself. Write the kind of book you want to read. You have to have faith in yourself and the process of writing.

4) Rejection, Rejection, Rejection…and How to Avoid It.

You can’t avoid rejection. That goes for writing just like everything else. You can toughen up to it. When you’re rejected try to take it as well as you can but don’t let it break your spirit ultimately. Jump into a bottle of beer if you must but then a day or two later start writing again. A certain writer I know (his initials are DG) once described the writer’s life by using the metaphor of Dante’s Inferno. DG, the Virgil to my Dante, told me about the circles of hell that exist for writers and at the time he told me I was just in the first circle and he was closer to the 5th or 6th circle. Hopefully, you read this long before you feel the cooling winds from leathery wings in the 9th circle. Cue Vincent Price laughter.

Publishing ain’t easy. I have a good friend named David Baker who has a novel about to come out from Touchstone called Vintage after many years. I can remember years ago we commiserated about the hopelessness of publishing our novels over beers. If being a writer is anything, it’s about taking an idea and making it real. You could say this about plots and characters, but turning your life into a writing life is making your life into what you imagine it to be. I’ve worked in scholarly publishing and I’ve been teaching for a number of years now and this has kept me anchored to my own writing life. Many well meaning people told me you couldn’t make a living being creative. “What are you going to do . . . write the great American novel or something?” It’s tough to make a living being creative but you just might be able to make a life. I remember my very well meaning stepdad (he passed away back in 2001) was pragmatic to a fault. If you pointed out a cool car he’d say, “You wouldn’t want to pay the insurance.” Likewise, if you mentioned how nice someone’s house was he’d opine, “You wouldn’t want the heating bill.” It was funny on the one hand but also it seemed to me like a point of view that did not allow room to dream. Well, last semester I taught two sections of creative writing at LSU. One day I was standing in front of the class talking about writing and then it hit me. Hey, look at me. I’m making a living being creative but really this is the life I’ve made with my wife and kids. See rule #1.