David Gessner's Blog, page 9

May 24, 2016

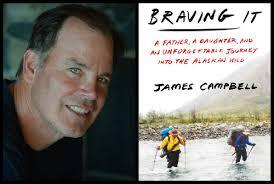

Braving It

James Campbell’s Braving It came out last week. It’s a great book, beautiful and original, the story of a father and a daughter and their adventures in Alaska. It’s about wildness and beauty but also about family and the encroaching fear of aging, of a father coming into a strange new time in his life just as his daughter is coming into a strange new time in hers. There has been nothing like it as far as the nature/father/daughter combination, and it is much more interesting to me than the theory/Last Child in the Woods-type stuff. Nothing feels forced and the relationship comes across as very real and moving. Meanwhile the writing about the natural world and the descriptions in general are great. Creosote in the stove is like scurrying mice and spruce trees are “weary white-robed pilgrims worshiping December’s new moon.” It’s both taut and lush, a tough combo to beat.

James Campbell’s Braving It came out last week. It’s a great book, beautiful and original, the story of a father and a daughter and their adventures in Alaska. It’s about wildness and beauty but also about family and the encroaching fear of aging, of a father coming into a strange new time in his life just as his daughter is coming into a strange new time in hers. There has been nothing like it as far as the nature/father/daughter combination, and it is much more interesting to me than the theory/Last Child in the Woods-type stuff. Nothing feels forced and the relationship comes across as very real and moving. Meanwhile the writing about the natural world and the descriptions in general are great. Creosote in the stove is like scurrying mice and spruce trees are “weary white-robed pilgrims worshiping December’s new moon.” It’s both taut and lush, a tough combo to beat.

I was honored that Jim asked me for a blurb. Here is what I came up with:

“Braving It is a beautiful and original book, an antidote to the screen-ification of modern life, and if there is any justice in the world it will be a huge hit. Wilder than Wild, it is also the most honest, moving and true story of a relationship between a father and a daughter that I have ever read. As the father enters the country of middle-age, and the daughter edges toward adulthood, they share an epic Alaskan  adventure that includes running rivers, polar and grizzly bears, and bitter cold. They also encounter something even more dangerous: fleeting time. They both seem to realize that they will never again have this moment, which,for all the book’s beauty, gives it an edge of sadness. Countering this sadness, is the gift that father gives daughter and that the writer gives the reader: the gift of the elemental now, of moments of wind, fire,water, snow, cold, beauty. And of equally primal moments of human love and connection.”

adventure that includes running rivers, polar and grizzly bears, and bitter cold. They also encounter something even more dangerous: fleeting time. They both seem to realize that they will never again have this moment, which,for all the book’s beauty, gives it an edge of sadness. Countering this sadness, is the gift that father gives daughter and that the writer gives the reader: the gift of the elemental now, of moments of wind, fire,water, snow, cold, beauty. And of equally primal moments of human love and connection.”

May 21, 2016

Lewis Robinson’s “Talk Shop” Podcast, with Yours Truly, Bill Roorbach

I enjoyed this talk with Lewis Robinson, which took place in his man cave with microphones, with an actual train going by. I sound like I’m almost asleep–and it’s true, I was very tired. But Lewis drew me out, and as David Olson said on Facebook: “This view into the writer’s mind is both fascinating and scary. In three words, I loved it!” I loved it, too, as Lewis is a new old friend, and an awfully smart, sweet guy, also a novelist.

I enjoyed this talk with Lewis Robinson, which took place in his man cave with microphones, with an actual train going by. I sound like I’m almost asleep–and it’s true, I was very tired. But Lewis drew me out, and as David Olson said on Facebook: “This view into the writer’s mind is both fascinating and scary. In three words, I loved it!” I loved it, too, as Lewis is a new old friend, and an awfully smart, sweet guy, also a novelist.

All episodes of Talk Shop are free: check out past interviews with Justin Tussing, Richard Russo, Susan Conley, Ron Currie Jr., Jen Blood, Monica Wood, Callie Kimball, Brock Clarke, Megan Grumbling, Gibson Fay-Leblanc, Kate Christensen, Phuc Tran, and Keith Lee Morris.

May 15, 2016

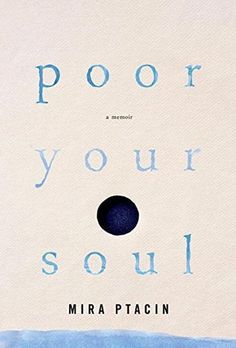

Table for Two: An Interview with Mira Ptacin

Debora: Poor Your Soul is such a lonely title. Very sad. Tell us about what’s inside your pages.

MIRA: Here’s the story: in 2008, at age twenty-eight, I accidentally got pregnant, despite taking birth control pills and never missing a dose. (I’m that 1 percent.) It wasn’t easy, I wasn’t happy about it, but I embraced it. And even though we’d only known each other for just three months, my boyfriend Andrew and I got engaged. Five months later, during the ultrasound that was to predict the sex of our baby, doctors found instead that our child had a constellation of birth defects and no chance of survival outside my womb. I was given three choices: terminate the pregnancy, induce delivery, or do nothing and inevitably miscarry. Poor Your Soul simultaneously traces my mother’s immigration from Poland at the age of twenty-eight, the adoption of her son Julian, his tragic death, and her reaction to the grief that followed. Both our stories examine how woman copes with the inevitable but unexpected losses a woman faces in the search for her identity. But overall, this isn’t a sad story. It’s a love story, about how I found love in my marriage, in my family, and for myself when everything around us was in chaos. It’s about perseverance and will.

Debora: A first book is a special undertaking. What was your experience with the process?

MIRA: Writing the book was my way of exorcising the trauma and sorrow out of me. It was what I did to heal, and it was also my job. It was very difficult selling the book, because for a long time, no publisher wanted to tackle a book that was not only a memoir (those are hard to sell/publish), but a book that involved a taboo/controversial subject: abortion. It took me one year to write the book, but almost eight years to find a publisher that I was happy with. Soho Press launched the book in January 2016, and I’m very happy and relieved, and have moved forward in my life as a human and as a mother. It’s almost like I put a tombstone on that part of my life.

Debora: The scene with your father and brother together in the car is really well written—the particular way the action moves, the way that ends with your father rocking your brother in his arms, and how you are there in your mind’s eye in the telling. How did you arrive at the right structure for the writing of your memoir?

Debora: The scene with your father and brother together in the car is really well written—the particular way the action moves, the way that ends with your father rocking your brother in his arms, and how you are there in your mind’s eye in the telling. How did you arrive at the right structure for the writing of your memoir?

MIRA: I didn’t know how to write about my emotions and feelings about the crash. I still don’t know how I feel, other than sadness and anger. I took it back to the basics: show, don’t tell. And I wrote it cinematically, with a few threads of scene weaving together. My inspiration was Jo Ann Beard’s essay “The Fourth State of Matter”. This helped me tremendously with structure. I was writing it like an omnipotent narrator, watching from above, watching the character of Mira as well.

Debora: What did you feel like when you finished the manuscript?

MIRA: I still haven’t read the final manuscript from beginning to end. I’m not sure if I ever will. I need some space from it. Perhaps in a decade or two I might read my memoir. Perhaps I will write another one in a decade or two. Perspectives change over time . . .

Debora: And now you live on an island in Maine. What is that like?

MIRA: Andrew and I have two kids now; Theo is three years old, and Simone is five months. I write from home, spend a lot of time in the woods with my kids and dogs. Peaks Island is a very strong community, very supportive, very quirky. I feel this is where we belong. The winters are full of solitude and peace, the summers are bright and vibrant. It is an island somewhat frozen in time, and I love it.

Debora: It’s an unusual place to end up. What took you there?

MIRA: We wanted to escape the hassle and rat race of New York City. We wanted to live a quiet and slow existence, take walks in the woods, not be burned for being ultra sensitive. You can read more about it here: http://writershouses.com/guest/the-wa....

Debora Black is a writer and athlete living in Steamboat Springs, CO

April 27, 2016

Ocracoke

What does it mean to love a vulnerable thing? A thing that won’t keep still or remain the same?

What does it mean to love a vulnerable thing? A thing that won’t keep still or remain the same?

I took the Cedar Island ferry to Ocracoke Island for the first time almost 10 years ago. On the boat, I became engaged in an animated conversation about birds with one of the deckhands. I pointed out a Northern gannet off the bow, a diving bird that migrates to Southern waters only in the winter.

“They come in with the cold,” he said. “We had a crowd of ducks — pintails — yesterday, too.”

From his emphasis on ducks, I assumed he was a hunter. Hunters are the only other group that knows birds as well as bird-watchers. We talked some more about what had been migrating through, and then he pointed ahead, to where 20 or so dolphins were swimming. Three veered off and headed straight for us, silver shining off their backs, and soon they were surf-riding in the bow right in front of the ferry. They were obviously doing it just for the fun of it, since they had originally been traveling in the opposite direction. Soon, other people got out of their cars and started snapping photos.

It was a delightful escort into the southern end of Ocracoke, and the delights continued ashore. I drove about halfway up the island before I pulled over at a beach access. The entrance was directly across from the pens that held the island’s famous Banker ponies, a species of small horse unique to Ocracoke that roamed wild on the marshes and beaches for centuries after they were left here by Spanish explorers.

When Ocracoke Lighthouse was built in 1823, the island was a barren strand. Today, homes are built up to the water’s edge. Photograph by Alistair Nicol.

The ocean’s rhythm greeted me as I walked out to the beach, the roaring crash followed by the seething slide of the water’s retreat. Ocracoke is a narrow spit of land approximately 20 to 25 miles out in the Atlantic, and almost the entire island remains undeveloped, the government having purchased it in 1937 and then establishing it, and more than 70 miles along other Outer Banks islands, as a national seashore in 1953. There was an uproar from business interests at the time, but the fruits of that historic purchase were now obvious. While much of the rest of the Outer Banks was covered with T-shirt shops and billboards, the beach here was pristine.

• • •The current threat to the island is not overdevelopment, but submergence. More than a few prominent coastal geologists believe that it will be underwater by the turn of the next century. Back when I first set foot on Ocracoke, I was still new to the state and had just begun my travels with Orrin Pilkey, the Duke coastal geologist who has long warned that buildings should be moved back from the shore. Orrin taught me about the way islands survive and change during storms, the way they handle hurricanes through a kind of elemental judo: storms push sand landward, and the island jumps over itself and grows on its back side. He would also tell me that if the predictions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change were correct — predictions he actually thought were too conservative — then Ocracoke faced a watery future.

But I wasn’t thinking about doom during my walk. A great cloud of gannets, the same type of bird I’d seen from the ferry, filled the sky 100 yards offshore. Northern gannets are long white birds with black wing tips that get their dinners by diving spectacularly into the sea. As I watched, they hovered far above the water like clouds before pulling their wings in to their sides and descending, straight down and fast, accelerating as they plunged into the water.

It was a pleasant surprise to find gannets in North Carolina. These cold-weather birds — these exclusively Northern birds, I had always falsely thought — hurling themselves into Southern waters, made me feel at home.

It was a couple of miles before I came upon another human being. A guy around my age was wearing waders and standing out in the water, surf casting. Had the beach been crowded, we would no doubt have ignored each other, but because it was just the two of us, we yelled enthusiastic greetings like long-lost friends. He told me he’d been catching red drum and blues earlier, but now he was after speckled trout.

“I’ve known this beach all my life. But every time I come down here, it’s a different beach, a new beach, in some way.”

I stayed on the shore while he stood in two feet of water, and we conversed over the crash of the waves. His name was Andy, and he wore a baseball hat pulled down low over his sun-browned face. In a few short minutes, he learned that I taught down at the university in Wilmington, and I that he had spent his whole life on this island. His accent was not particularly thick.

I told him that I was hoping to see a Banker pony on the beach. “Are all the ponies penned in?” I asked.

“Yeah, they had to do it once they built the highway,” Andy said. “They couldn’t have ponies becoming roadkill. The ponies got lots of room to roam still, miles, really, but I’ll tell you, it was something before they put the fences up. You could be standing out here fishing or out in the marsh clamming, and suddenly a horse would wander by.”

Andy wasn’t alive back when the government claimed the beaches as parkland, so I asked how his family reacted.

He laughed.

“Oh, my grandparents were very upset. Enraged, really. They hated being told their land wasn’t their land and that they couldn’t even hunt on it. But now look at what we’ve got. It’s hard to argue with this.” He held his free hand out, palm up, as if putting the beach and ocean on display.

I wasn’t about to argue. In these troubled days, it seems we rarely feel delight without accompanying anxiety. I already understood that, despite its beauty, all was not rosy with Andy’s home beach. Although I’d only just begun my travels with Pilkey, even an uneducated eye could sense the vulnerability of the land. On Ocracoke, creeks cut across the island, places where, with a quick glance, you could see the ocean on one side and the marsh on the other. It wouldn’t take much for these creeks to become rivers.

• • •I could have asked Andy if he thought his home island would still be here when his grandchildren’s children were born, but the sun was on my face and I was feeling good, and I decided not to pursue that apocalyptic possibility. Instead, I asked him if it was possible to notice the beach changing day to day. He thought about it awhile and pulled on the brim of his baseball hat.

“I’ve known this beach all my life,” he said. “But every time I come down here, it’s a different beach, a new beach, in some way. Something’s changed, you know?”

I nodded. It might have been at that very moment that I decided I would be returning to Ocracoke. Soon. There are places you need a lifetime to warm up to, but other places you immediately sense are special.

We talked for a while longer, and then, by way of saying goodbye, I told him that I thought I might be falling in love with his island.

“You should move out here,” he said before I walked away. “You can quit your job and teach in our one-room schoolhouse.”

I laughed and waved goodbye. It was a long walk back to the car, but a good one. Before I cut up off the beach, I took one last look out at the white birds and dark blue water, already falling hard for this impermanent place, already feeling the usual mix of love and loss for the ever-changing land.

April 23, 2016

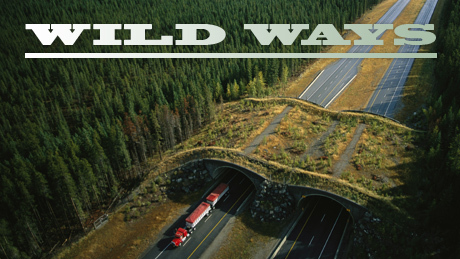

Wild Ways

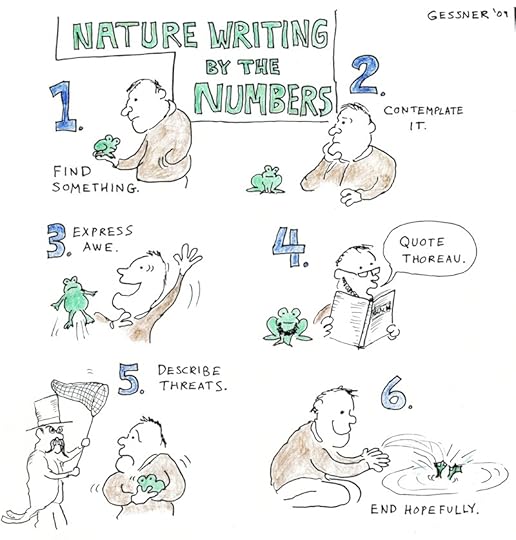

I have mocked the editor-encouraged tendency of all nature essays and articles to “end hopefully,” no matter how dire the subject. But on this Earth Day I’ll throw a little hope into the mix. Last Wednesday Nova aired a show called Wild Ways, featuring the idea of connecting large patches of the wild with wilderness corridors. Thanks to people like Banff’s Harvey Locke, who is featured in the show, this is no longer as far-fetched an idea as it once was.

I have mocked the editor-encouraged tendency of all nature essays and articles to “end hopefully,” no matter how dire the subject. But on this Earth Day I’ll throw a little hope into the mix. Last Wednesday Nova aired a show called Wild Ways, featuring the idea of connecting large patches of the wild with wilderness corridors. Thanks to people like Banff’s Harvey Locke, who is featured in the show, this is no longer as far-fetched an idea as it once was.

As I wrote in All the Wild that Remains: “Rewilding is a radical idea, but so was saving parkland when it was first proposed. With the creation of the parks we did something that no one expected, something no one had ever done. Now imagine if parks became not just museums of remnant ecosystems but beads on a much larger rosary, stopover points in a migratory corridor that runs up and down the continent’s spine. Anyone who looks too long at the environmental problems facing us can become overwhelmed and dispirited. But the thought of rewilding gives me hope. It is big. It is bold. It excites imaginations. And, as ideas go, it is wild.”

Here is the link to info about the show.

Previous mockery mentioned above:

April 13, 2016

Big Sur!

When Wendell Berry returned to Kentucky as a young writer he said that one of the challenges was that it was unwritten ground. I always thought Cape Cod was the opposite, over-written ground, where every rock and tree already had a poem or essay written about it. Well, Big Sur, where I spent a couple days last week, gives Cape Cod a run for its money. As beautiful and wild as the place was, almost everything I saw triggered a literary association, starting with the great sea cliffs I knew until then only through the poetry of Robinson Jeffers….”We must uncenter our minds from ourselves/We must unhumanize our views a little/and become confident/As the rock and ocean we were made from.”

When Wendell Berry returned to Kentucky as a young writer he said that one of the challenges was that it was unwritten ground. I always thought Cape Cod was the opposite, over-written ground, where every rock and tree already had a poem or essay written about it. Well, Big Sur, where I spent a couple days last week, gives Cape Cod a run for its money. As beautiful and wild as the place was, almost everything I saw triggered a literary association, starting with the great sea cliffs I knew until then only through the poetry of Robinson Jeffers….”We must uncenter our minds from ourselves/We must unhumanize our views a little/and become confident/As the rock and ocean we were made from.”

All photos by Deborah Lorenc

Speaking at the Henry Miller library I remembered how much I loved Henry Miller in my twenties, and it occurred to me how much Miller (“I am the happiest man alive”) must have influenced Abbey (“It was the happiest night of my life”),

My generous host, Chris Lorenc, took me on a drive down the Old Coast Road and quoted Jeffers “Return” as we approached the Big Sur River: “I will touch things and things and no more thoughts/That breed like mouthless May-flies darkening the sky…”

Best of all, I got to spend a night in Chris’s cabin, just canyon over from the Ferlinghetti’s, the place where Kerouac lived out the events in Big Sur, my favorite of his books,and one, I think, that in its language play paved the way for some great books of the ’60s (including Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.)

New friends, Chris, Patrick and Magnus.

Speaking at the Henry Miller Museum.

April 12, 2016

Lundgren’s Lounge: “Stop Here, This is the Place,” by Susan Conley and Winky Lewis

Words and images on the page have a variety of purposes: to instruct, to persuade, to ediify, to entertain, to evoke… and it is this last that comes to mind while reading and looking at Stop Here: This is the Place, A Year in Motherhood, a unique collaboration between photographer Winky Lewis and writer Susan Conley.

Susan Conley

What this book exquisitely evokes is summertime childhood in Maine, a place where rock meets ocean. Co-creators Lewis and Conley are neighbors and one senses, sisters. Raising families next to one another, they wondered… what if we began starting each week with a photograph (Winky), to which author Susan would respond with a small narrative? They saw one another daily, often multiple times, as they ferried kids to school and sports and plays and events, all while trying to shoehorn in some room for their own lives. But throughout the yearlong process, they never spoke about their collaboration.

Winky Lewis and subject

There are intriguing understories in this artistic partnership … the emotional tumult that accompanies coming of age while female in contemporary America, or the tensions that accompany a woman and her daughter as they negotiate the shoals of occupying physical and emotional space together. What the book most evoked for me was a sense of endless days outside, arriving after an arduous bike ride to the lagoons and backponds of the spring-fed Plover River…no matter that for me it was Wisconsin, not Maine; the effect of youth, unrestrained and let loose in the natural world is, I suspect, the same wherever it occurs. A sense of unfettered possibility and relationships: human to the world and human to human, that cannot be forged anywhere else.

As I read and looked, my initial skepticism that the work might be too insular, reflecting but a small corner of the world, were allayed. This is a resplendent work of art and in depicting that place where ocean meets land, Conley and Lewis have captured the universal wonders and mysteries of childhood and motherhood, regardless of where they happen.

This is a work deserving of our time and the inevitable appreciation that will follow.

“In boyland, where he lives, all the boys go into the house by the harbor and eat any food they can find. Then they go out. They swim in the ocean and lie on the rocks like seals, again and again.” from Stop Here: This is the Place

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a friend of Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

March 31, 2016

Immortal Freemasonry Explained

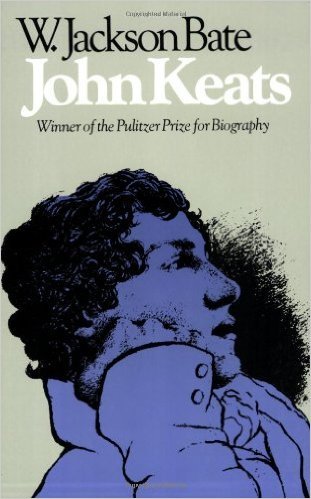

It was Keats who coined the highfalutin phrase “immortal freemasonry.” What it means in simple English is this: dead writers are alive to us.

It was Keats who coined the highfalutin phrase “immortal freemasonry.” What it means in simple English is this: dead writers are alive to us.

I have no idea why this idea, of connections and literary lineage, kept weaving through my dreams last night. I am in LA at the Associated Writers and Writing Programs conference, an event where my brain is usually at its soggiest, and my dream life is rarely so highbrow. But last night I couldn’t stop thinking, or sleep-thinking, about teachers and students and the way we pass things down over the generations.

Maybe this had to do with reading about my former student Carson Vaughan’s encounter with Jim Harrison before he died. (Nina and I were lucky enough to have a similar encounter with John Updike not long before he died.) Or maybe it has to do with the fact that later today at a ceremony at our school a friend is going to quote from a T.S.Eliot poem I suggested about the way the past is present.

But back to the definition. The idea is that writers are “freemasons,” part of a secret society, and that membership in that society doesn’t end just because you are dead. This can be as simple as picking up a dead writer’s book. Inert print becomes something else when another mind revives it. For me a perfect example is the liveliness of Montaigne, despite being 500 years dead, and I have recently been fond of quoting Emerson’s line about him: “Cut his sentences and they bleed.”

Sometimes though, as in Carson’s case, there is a flesh and blood encounter to compliment the one on the page. And maybe, at AWP 2067, there will be panel called The Legacy of Carson Vaughan, after which the elderly Vaughan will lean on his cane and tell one of the young writers on the panel about his encounter with Harrison, passing the experience on.

And maybe at some point a young woman in our creative writing program will come to me and say that she has re-discovered the poetry of Eliot, not in the dry Wasteland-y way that we were taught it in high school, but in a new fresh way, entering through some of the older less gnarled poems, and finding there something she can adapt and put to use in her own work, almost as if the old poet were talking directly to her.

And if this happened I would surely re-tell a story I have told and written about many times before. I would tell her about the time I visited the great biographer, Walter Jackson Bate, at his farmhouse in New Hampshire and how one evening, after a couple of drinks he read these lines to me from Eliot’s “East Coker” in Four Quartets:

Home is where one starts from. As we grow older

The world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated

Of dead and living. Not the intense moment

Isolated, with no before and after,

But a lifetime burning in every moment

And not the lifetime of one man only

But of old stones that cannot be deciphered.

There is a time for the evening under starlight,

A time for the evening under lamplight

(The evening with the photograph album).

Love is most nearly itself

When here and now cease to matter.

Old men ought to be explorers

Here and there does not matter

We must be still and still moving

Into another intensity

For a further union, a deeper communion

Through the dark cold and empty desolation,

The wave cry, the wind cry, the vast waters

Of the petrel and the porpoise. In my end is my beginning.

And then I would tell her what Bate said after I thanked him for the reading—”Thank you for listening. It’s been years since I read poetry out loud. The last time I read this piece was at Eliot’s memorial service.”—and how I felt suddenly transported out of my normal life and into some mythical literary stratosphere.

And then, finally, I would say something to my young student, that I’m sure many freemasons have said to new initiates over the years:

“Welcome to the club.”

March 30, 2016

March 28, 2016

Publication Day: Where’s my Marching Band?

When I was a child, my father’s best friend hired a marching band to show up at our house on my mother’s birthday one year. This was one in a series of outlandish birthday events he arranged for her, but it remains the most memorable in my mind, seeing that band marching up our street with the neighbors wondering in disbelief whether they had forgotten to mark some holiday or parade on our calendar.

When I was a child, my father’s best friend hired a marching band to show up at our house on my mother’s birthday one year. This was one in a series of outlandish birthday events he arranged for her, but it remains the most memorable in my mind, seeing that band marching up our street with the neighbors wondering in disbelief whether they had forgotten to mark some holiday or parade on our calendar.

That event left such a permanent mark on me that I still consider the arrival of a marching band as the ideal way to celebrate a momentous event in one’s life—which, in my case these days, takes the form of the publication of a new book. Each time one of my books has been published, I sit around the house expectantly all day secretly hoping that a marching band will appear around the corner at any moment, the leader carrying a box of my author copies, neighbors standing agog in their driveways, my family smiling and proud.

It hasn’t happened yet.

The publication day for my newest book, Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning, came and went in mid-March without so much as an oboist serenading me from the driveway. But even though that has been my experience with each of my five books, it still has not diminished this expectation that on publication day something amazing will happen. I’ll be lying in bed and my wife, an early riser, will call from the kitchen: “Jim, get down here, Katie Couric’s on the phone!” Or I will log into my e-mail to find that I have been invited to Stockholm for a reason that they can’t state right now, but let’s just say they need me there for an evening event and I should wear my tuxedo.

Here’s what happens instead on publication day: exactly what I make happen. And that, my friends, is the hard truth that I have to re-learn with the publication of every new book. Almost nothing happens, on publication day or any other day, unless I make it happen.

Of course all of us who write books these days know that we are the primary marketers of our own work. We have to write for print and online publications on the topics of our books, getting the title in our bylines; we have to reach out to whatever friends and contacts we have in the media to wrangle publicity; we have to hump our suitcases and author copies to a dizzying array of venues—bookstores, colleges and universities, the homes of friends and supporters—in order to get the word out. Publishers count on the author as the primary sales force for their own books.

But it still feels to me like something unique should happen on publication day. Maybe they could send me a bouquet of flowers or a box of chocolates. Or perhaps a phone call from my editor saying “Good work, Jim! Nailed it again!” Perhaps the college where I teach should have offered to have someone teach my classes for me, and I could have sat amidst a pile of my author copies in the student center, just sort of lording it over all passersby that today was my special day, the day on which I have published a book and the rest of you have not.

Instead, my publication day schedule included three meetings on campus, two dog walks, packing some boxes for an upcoming house move, and checking my rankings on amazon around four hundred times. This was an especially strange publication day because although the official publication date was March 14th, the book actually and unexpectedly appeared in stock on amazon on March 7th. Good lord, I thought to myself when I saw it available a week early, this is going to be very awkward if a marching band shows up on March 14th!

But there was no marching band. There never is. And, I really must resign myself to it, there never will be.

I let myself do no real work on publication day, in exchange for the lack of a marching band, but the next day I was back at work, putting in a few hundred words on the next project. What else can you do? This is the way I have been made, and apparently the lack of celebrations on publication day won’t change that. Writers must write, marching bands or no.

The same friend of my parents who arranged the marching band for my mother once sent me a note about my writing. At that time I was still attempting to write fiction, and I was most of the way through a novel that I had shown to my mother and she had spoken about in glowing terms to her friend (if only my mother had been an acquisitions editor!). The note that he sent me read something like this: “In my life I have probably known 50 people who said they wanted to be writers. You are the only one I know who actually writes. Congratulations on pursuing a dream.”

Sometimes when the writing life disappoints, and I am waiting for the trumpets and drums that never arrive, I think about that note, and I carry on. The next publication day awaits.

More from Jim Lang at @LangOnCourse or http://www.jamesmlang.com.