David Gessner's Blog, page 100

November 11, 2011

Learning to Surf

We are in the process of converting and re-stocking are other categories, including "Our Best American Essays," which this is a part of. To read this essay in its original form as it appeared in Orion magazine (beautiful painting and all), click here.

We are in the process of converting and re-stocking are other categories, including "Our Best American Essays," which this is a part of. To read this essay in its original form as it appeared in Orion magazine (beautiful painting and all), click here.

LEARNING TO SURF

by David Gessner

Out just beyond the breaking waves, they sit there bobbing, two groups of animals, avian and human, pelicans and surfers. As they rise and fall on the humps of water, the pelicans look entirely unperturbed, their foot-long bills pulled like blades into scabbards, fitting like species-wide puzzle pieces into the curves of their throats. The surfers, mostly kids, look equally casual. In fact one girl takes this to an almost ostentatious extreme: she lies on her back on the surfboard, looking up at the sky, with one leg crossed over the other in an exaggerated attitude of relaxation. For the most part the birds and surfers ignore each other, rising up and dropping down together as the whole ocean heaves and then sighs.

Pelicans are particularly buoyant birds and they bob high on the water as the surfers paddle and shift in anticipation. There is no mistaking that this is the relatively tense calm of before, rest before exertion. Soon the waves pick up and the surfers paddle furiously, gaining enough speed to pop up and ride the crests of breaking surf. They glide in toward the beach where I stand, the better ones carving the water and ducking under and cutting back up through the waves.

We only moved to this island town a month ago, but I have been here long enough to know that those who pursue this sport are guided by a kind of laid-back monomania. Each morning I bring my four-month old daughter down to the local coffee shop, and each morning the talk is of one thing. It isn't only the southern lilt that is new to me, but the surfing lingo. The ocean, I've learned, is always referred to as "it."

"What did it look like this morning?" one surfer asked another a few mornings back.

"Sloppy."

Remembering my own early morning glance at the ocean I could understand what he meant, the way the waves came from the northwest, while another group muscled up from the south, and how the two collided and kicked up. Aesthetically it was beautiful, but practically, at least from a surfer's point of view, it made for a landscape of chop.

Another morning I heard this:

"How does it look today, dude?"

"Small."

"Nothing?"

"You can go out there if you want to build your morale."

It's easy enough to laugh at these kids, but I like the physical nature of their obsession, the way their lives center on being strong animals. In When Elephants Weep, Jeffrey Masson speculates that animals feel funktionslust, a German word meaning the "pleasure taken in what one can do best." The strongest of the surfers, the ones who have grown up on the waves, must certainly feel this animal pleasure as they glide over and weave through the water.

I watch the surfers for a while, but once the pelicans lift off the water, I turn my focus toward even more impressive athletic feats. Pelicans are huge and heavy birds, and the initial lift-off, as they turn into the wind and flap hard, is awkward. But once in the air they are all grace. They pull in their feet like landing gear and glide low between the troughs of the waves, then lift up to look for fish, flapping several times before coasting. If you watch them enough, a rhythm reveals itself: effort, glide, effort, glide. As a sports fan, I love watching birds dive, and the pelicans do not disappoint. They are looking for small fish–menhaden or mullet most likely–and when they see what they are looking for they gauge the fishes' depth, and therefore the necessary height of the dive, a gauging guided by both instinct and experience. Then they pause, lift, measure again, and, finally plunge. It's quite a show. The birds bank and twist and plummet, a few of them turning in the air in a way that looks like pure showing off, but all of them following their divining rod bills toward the water. If they were awkward in take-off, now they are glorious.

There is something symphonic about the way the group hits the water, one bird after another: thwuck, thwuck, thwuck. At the last second before contact they become feathery arrows, thrusting their legs and wings backward and flattening their gular pouches. They are not tidy like terns and have no concern for the Olympian aesthetics of a small splash, hitting the surface with what looks like something close to recklessness. As soon as they strike the water instinct triggers the opening of the huge pouch, and it umbrellas out, usually catching fish, plural. While still under water they turn again, often 180 degrees, so that they will emerge facing into the wind for take off. And when they pop back up, barely a second later, they almost instantly assume a sitting posture on the water, once again bobbing peacefully as they drain their pouches. It's a little like watching a man serve a tennis ball who then, after his follow through, hops immediately into a La-Z-Boy.

* * *

The pelicans calm me, which is good. I have tried to maintain an attitude of relaxation since moving to this island, but at times I feel as if I've lost my balance. The heat has begun to make me act in questionable ways. Each morning when I lift my daughter into our un-air conditioned Honda Civic, I feel as if I'm sliding her into a kiln. This has led me to a place I never thought I'd go. While I am a creature known as a nature writer, I am on the verge of doing something unspeakable and preposterous: buying an SUV. It's a small SUV, but still. I have raged against these abominations most of my life and when we lived in the West I published an essay called "Big Cars, Little Men." But now I find that the cars we want to buy, the cool green enviro-station wagons, are out of our price range, and that thisToyota, which gets the same mileage, is not. The important thing, I tell myself in a near panic, is to get my daughter out of the kiln.

I am ready to buy the thing, to pull the trigger, when I am saved, at least temporarily, from an unexpected source. TheToyotaguy himself calls with some news. Our credit report has come back and our loan has been rejected.

I ask why.

"You have weak stability," he tells me, reading from the report.

Yes, of course.

I nod and consider the poetry of his words.

* * *

But there are other moments, moments when–despite my wobbly confidence–I have glimpses that this may not be such a bad place to live. With summer ending the parking lots have begun to empty: there are fewer beachwalkers and more pelicans. Each morning I take long walks with Hadley, and have begun to take field notes on my daughter. Many things have caught me off guard about being a father, but the most startling thing has been the sheer animal pleasure. "Joy is the symptom by which right conduct is measured," wrote Jospeh Wood Krutch of Thoreau. If that's true then my conduct must be excellent these days.

Last week our friend Karen, a doctor fromSan Francisco, said to my wife Nina that you never feel so connected to the animal kingdom as when you have a child. Nina agreed. She has felt that way many times since the birth, but never so much as yesterday morning when she couldn't get Hadley's face clean. Milk had crusted in our daughter's ears and above her eyebrows and the wash cloth wasn't working. So Nina did what came naturally: she put the wash cloth aside and licked Hadley until she was clean.

What hits me daily with consistent impact is the fact of my daughter's creatureliness. This squirming little ape-like animal, barely two feet high, somehow has been allowed to live in the same house with us. Or as another friend of Nina's put it: "They're the best pet you'll ever have."

Today I hike down this new beach, carrying Hadley in a papoose-like contraption on my chest, trying to rock her to sleep. On good days we make it all the way to the south end of the island where we stare out at the channel. If I feel uprooted having moved here, nothing cuts through doubt quite like this new ritual of walking while observing the birds and surfers.

This morning we watch two immature, first-year pelicans fly right down over the waves, belly to belly with their shadows. It's exhilarating the way they lift up together and sink down again, rollercoastering, their wings nicking the crest of the waves. Eight more adult birds skim right through the valley between the waves, by the surfers, sweeping upward before plopping onto the water.

Feeling that it's only polite to get to know my new neighbors, I've begun to read about the birds. I've learned that the reason they fly through the troughs between the waves is to cut down on wind resistance, which means they, like the surfers they fly by, are unintentional physicists. When I first started watching the birds I kept waiting to hear their calls, expecting a kind of loud quack-quork, like a cross between a raven and a duck. But my books confirm what I have already noticed, that adult pelicans go through their lives as near mutes. Whether perched atop a piling in classic silhouette or crossing bills with their mates or bobbing in the surf, they remain silent.

Another group of adult birds heads out to the west, toward the channel, as Hadley and I head home. Before moving here I never knew that pelicans flew in formations. They are not quite as orderly as geese–their Vs always slightly out of whack—and the sight of them is strange and startling to someone from the North. Each individual takes a turn at the head of the V, since the lead bird exerts the most effort and energy, while the birds that follow draft the leaders like bike racers. These platoons fly overhead at all hours of day, appearing so obviously prehistoric that it seems odd that people barely glance up, like ignoring a fleet of pterodactyls.

Yesterday I saw one of the birds point its great bill at the sky and then open its mouth until it seemed to almost invert its pouch. My reading tells me that these exercises are common, a way to stretch out the distensible gular pouch so that it maintains elasticity. Even more impressive, the pouch, when filled, can hold up to twenty-one pints–seventeen and a half pounds–of water.

"I have had a lifelong love affair with terns," wrote John Hay, my friend back onCape Cod. I've come to pelicans late: our affair can never be lifelong. But I am developing something of a crush.

* * *

I'm not a good watcher. Well, that's not exactly true. I'm a pretty good watcher. It's just that, sooner or later, I need to do more than watch. One thing I love about the pelicans is the wild contact of their dives, and contact is something you can't get from just watching. So today I am floating awkwardly on my neighbor Matt's surfboard, paddling with my legs in a frantic eggbeater motion, attempting this new sport in this new place while watching the pelicans fly. It's a great way to birdwatch it turns out, though you can't bring your binoculars. The pelcians fly close to my board, and for the first time I understand how enormous they are. I've read that they are fifty inches from bill to toe, and have six-and-a-half foot wingspans, but these numbers don't covey the heft of their presence. One bird lands next to me and sits on the water, tucking its ancient bill into its throat. Up close its layered feathers look very unfeather-like, more like strips of petrified wood. I watch it bob effortlessly in the choppy ocean. Most birds with webbed feet have three toes, but brown pelicans have four, and their webbing is especially thick. While this makes for awkward waddling on land, it also explains how comfortable the birds look in the water.

I'm not nearly as comfortable. Two days ago I spent an hour out here with Matt as my teacher, and yesterday we came out again. Despite his patience and coaching, I didn't stand up on my board, in fact I never made more than the most spastic of attempts. Today has been no better. So far the best things about surfing have been watching the birds and the way my body feels afterward when I am scalding myself in our outdoor shower. But the basics have eluded me. So it is with some surprise that I find myself staring back with anticipation as a series of good waves roll in and it is with something close to shock that I find myself suddenly, mysteriously, riding on top of that one perfect (in my case, very small) wave. Before I have time to think I realize that I am standing, actually standing up and surfing. The next second I am thrown into the waves and smashed about.

But that is enough to get a taste for it.

* * *

I have now been practicing my new art for three days. The pelicans have been practicing their ancient one, as a species, for thirty million years. It turns out the reason they look prehistoric is simple: they are. Fossils indicate that something very close to the same bird we see today were there when the very first birds took flight. They were performing their rituals—diving, feeding, courting, mating, nesting—while the world froze and thawed, froze and thawed again, and while man, adaptable and relatively frenetic, came down from the trees and started messing with fire and farming and guns.

Readingabout pelicans has proven an interesting study of anthropomorphism. While any human would say the birds are slightly funny looking, what struck me first was the grace of their flight. Not so the early ornithologists. In 1922, Arthur Cleveland Bent wrote of their "grotesque and quiet dignity" and called them "silent, dignified and stupid birds." A contemporary of Bent's, Stanley Clisby Arthur, went even further, describing the pelicans' habits with something close to ridicule. Arthur writes of the pelicans' "lugubrious expressions" and "ponderous, elephantine tread" and "undemonstrative habits," and says of their mating rituals that "they are more befitting the solemnity of a funeral than the joyous display attending most nuptials." His final insult is calling their precious eggs "a lusterless white."

Apparently, when it comes to pelicans, even modern writers feel the need to lay it on thick: as I read I make a list of words that includes "gawky," "awkward," "comical," "solemn," "reserved," and, simply, "ugly." I had already assigned the role of shorebird comedian to the oystercatcher, with its orange Jimmy Durante nose, and it never occurred to me that pelicans were preposterous. But I'll admit that recently as I kayaked by a sandbar full of birds, I laughed while watching a pelican waddle though a crowd of terns, like Gulliver among the Lilliputians. But "ugly" seems just mean-spirited.

More forgivable, perhaps, are those who call the birds "dignified" and "solemn," since it is natural to project qualities of depth upon those who are quiet, even with human beings. While we are quick to call raptors "proud," this is not a word that comes to mind with a pelican. But if they lack the athletic, cocksure air of hawks and eagles, their flight is every bit as confident and athletic (though they're not as given to showiness and derring-do.)

When not seeing pelicans as comic or grotesque, human beings often describe them as sedate and sage-like. Perhaps this springs from a dormant human need to see in animals the qualities we wish we had. If hell is other people, as the saying goes, then heaven is other creatures. Compared to our own harried, erratic lives, the lives of the pelicans seem consistent, reliable, ritualistic, as befits a bird that has been doing what it's being doing for thirty million years.

And that, I have to admit, is one of the things I see in pelicans, too. Something, if you will pardon the terrible pun, unflappable. Sure they flap a little, but they also glide with grace, with none of that desperate duck flapping that makes you worry that cormorants will suddenly crash land or hurtle into a rock. Calling pelcians unperturbable is not mere projection either. Researchers at their nests confirm it: they can walk among brown pelican ground nests while barely getting dirty looks, while the same researchers would lose an eye at an eagle eyrie or be endlessly harassed at a tern colony. Nor is it projection to say that the lives of pelicans are simpler, more filled with ritual and in touch with the elemental world. Compared to their deep consistent lives, my own feels constantly re-invented, improvised. But before I get too down on myself, and my species, I need to remember that that's the kind of animal I am, built for change, for adaptation. Long before we became dull practioners of agriculture, human beings were nomads, wanderers, capable of surviving in dozens of different environments.

Though born barely able to hold their heads up, and though at first fed regurgitated food by their parents, newborn pelicans spend only a short time under their parents' care and fledge within three months. The one year olds I watch flying overhead are already almost as capable as their parents, while my daughter will remain relatively helpless for many years to come. But this too makes evolutionary sense: one reason for our long infancy and childhood is to give the human mind time to adapt creatively to thousands of different circumstances. Pelicans, on the other hand, are ruled by a few simple laws and behaviors. Still, at the risk of romanticizing, I like the calm the birds exude, the confidence in doing what they do, the sense of timelessness, of ritual and grace.

We humans face a different set of problems. Our bodies still run on rhythms we only half understand (and often ignore), and we have adapted ourselves beyond ritual. To a certain extent, all rules are off. The life of the farmer or hunter, the life that all humans lived until recently, directly connected us to the world of animals and plants, and to the cycles of the seasons. Without these primal guidelines, we are left facing a kind of uncertainty that, on good days, offers a multifarious delight of options, and on bad days offers chaos. Ungrounded in this new place, I feel particularly sensitive to both possibilities. And while it isn't comfortable building a foundation on uncertainty, at least it has the advantage of being honest. Maybe in this world the best we can do right now is not to make false claims for certainty, and try to ride as gracefully as we can on the uncertain.

It's true I may have weak stability, as theToyotaguy said. In my defense I remind myself of what Montaigne wrote: "Stabilty itself is nothing but a more languid motion."

Stability isn't my species strength. Adaptation is.

* * *

The human brain is no match for depression, for the chaos of uncertainty and uprootedness. To try to turn our brains on ourselves, to think we can solve our own problems within ourselves, is to get lost in a hall of mirrors. But a world exists beyond the merely human world, and that is a reason for hope. From a very selfish human perspective, we need more than the human.

My mind may not be a match for depression, but the ocean is. This morning I paddle out beyond the breakers and lie on my back on the surfboard just like the girl I saw in early fall,. But while my legs may be crossed casually, I spend most the time as I lie there worrying about falling off. Even so, as I bob up and down on the waves, the whole ocean lifting and dropping below me, my niggling mind does quiet for a minute. And then it goes beyond quiet. I'm thinking of Hadley, sitting up now and holding her own bottle, and I feel my chest fill with the daily joy these small achievements bring. She will be a strong girl I suspect, an athlete. And, no doubt, she will become a surfer if we stay here, delighting in her own funcktionslust.

In this new place I must try new things, but still cling to old loves. Birds have always helped me live, have always lifted me, and as I float on my board the pelicans don't fail to deliver. As they fly overhead I notice that there is something slightly backward-leaning about their posture, particularly when they are searching for fish, as if they were peering over spectacles. From this angle, directly below, they look like giant kingfishers, with their pointy heads and hovering manner. But when they pull in their wings they change entirely: a prehistoric Bat Signal shining overGotham. Then I notice one bird with tattered feathers whose feet splay out crazily before he tucks to dive. When he tucks, dignity is regained, and the bird shoots into the water like a spear.

Inspired by that one bird, I decide to make my own attempt at flight. I catch a few waves, but catch them late and so keep popping wheelies and being thrown off the surfboard. Then, after a while, I remember Matt telling me that I am putting my weight too far back on the board. So on the next wave, almost without thinking, I shift my weight forward and pop right up. What surprises me most is how easy it is. I had allotted months for this advancement, had assumed that getting up was a goal to be long worked toward. But here I am, suddenly standing, flying in toward the beach on top of a wave, its energy surging below. A wild giddiness fills me. It's cliché to say that I am completely in the present moment as this happens, and it is also not really true. Halfway to shore and I'm already creating a narrative, imagining telling Nina about my great success, and near the end of my ride, as the great wave deposits me in knee deep water, I find myself singing the Hawaii 5-0 theme song right out loud.

Though no one is around I let out a little hoot, and by the time I jump off the board I'm laughing out loud. A week ago I watched some kids, who couldn't have been older than twelve or thirteen, as they ran down the beach on a Friday afternoon. Happy that school was out, they sprinted into the water before diving onto their boards and gliding into the froth of surf. I'm not sprinting, but I do turn around and walk the surfboard out until I am hip deep, momentarily happy to be the animal I am, my whole self buzzing fom a ride that has been more the result of grace than effort. Then, still laughing a little, I climb on top of the board and paddle back into the waves.

* * *

I could end on that note of grace. But it wouldn't be entirely accurate. The year doesn't conclude triumphantly with me astride the board, trumpets blaring, as I ride that great wave to shore. Instead it moves forward in the quotidian way years do, extending deep into winter and then once again opening up into spring. As the days pass my new place becomes less new, and the sight of the squadrons of pelicans loses some of its thrill. This, too, is perfectly natural, a process known in biology as habituation. Among both birds and humans, habituation is, according to my books, the "gradual reduction in the strength of a response due to repetitive stimulation." This is a fancy way of saying we get used to things.

While the pelican brain repeats ancient patterns, the human brain feeds on the new. On a biological level novelty is vital to the human experience: at birth the human brain is wired so that it is attracted to the unfamiliar. I see this in my daughter, as she begins to conduct more sophisticated experiments in the physical world. True, all of these experiments end the same way, with her putting whatever she is experimenting on in her mouth, but soon enough she will move on to more sophisticated interactions with her environment. Although pelicans of her equivalent age are already diving for fish, she is helpless unless we feed her and only just beginning her attempts at language and locomotion. But as a homo sapien, she can afford to spot Pelecanus occidentalis a lead, knowing she will gain ground later. Her long primate infancy will allow her relatively enormous brain to develop in ways that are as foreign to the birds as their simplicity is to us, and will allow that brain to fly to places the birds can never reach.

While I acknowledge these vast differences between our species, there is something fundamentally unifying in the two experiences of watching the pelicans and watching my daughter. There is a sense that both experiences help me fulfill Emerson's still-vital dictum: "First, be a good animal." For me fatherhood has intensified the possibility of loss, the sense that we live in a world of weak stability. But it has alos given me a more direct connection to my animal self, and so, in the face of the world's chaos, I try to be a good animal. I get out on the water in an attempt to live closer to what the nature writer Henry Beston called "an elemental life."

I keep surfing into late fall, actually getting up a few times. But then one day I abruptly quit. On that day "it" is big, much too big for a beginner like me. I should understand this when I have trouble paddling out, the waves looming up above me before throwing my board and self backward. And I should understand this as I wait for the waves, the watery world lifting me higher than ever before. But despite the quiet voice that tells me to go home I give it a try, and before I know it I am racing forward, triumphant and exhilarated, at least until the tip of my board dips under and the wave bullies into me from behind, and I am thrown, rag-doll style, and held under by the wave. Then I'm tossed forward again and the board, held to my foot by a safety strap, recoils and slams into my head. I do not black out: I emerge and stagger to the shore and touch my hand to the blood and sand on my face. The next night I teach my Forms of Creative Nonfiction class with a black eye.

So that is enough, you see. One of the new countries I am entering is that of middle age, and the world doesn't need too many middle aged surfers.

I feared fatherhood, but most of the results of procreation have been delightful ones. One less than delightful result, however, is the way that disaster suddenly looms around every corner–disaster that might befall my daughter, my wife, my self. No sense adding "death by surfing" to the list.

* * *

While I have naturally begun to take the pelicans for granted, they still provide daily pleasures throughout the winter. What I lose in novelty, I gain in the beginnings of intimacy. I see them everywhere: as I commute to work they fly low in front of my windshield; they placidly sit atop the pilings while I sip my evening beer on the dock near our house; they bank above as I drive over the drawbridge to town. My reading tells me that in March they begin their annual ritual of mating: a male offers the female a twig for nest building and then, if she accepts, they bow to each other before embarking on the less elegant aspect of the ritual, the actual sex, which lasts no more than twenty seconds. It doesn't sound particularly lugubrious to me, but then I haven't seen it. These rituals are taking place in privacy, twenty miles south on a tiny island in the mouth of theCape Fear River. The eggs are laid in late March or early April and a month-long period of incubation begins.

Around the mid-point of incubation, my human family achieves its own milestone. Throughout the spring I have continued to carry my daughter down the beach to watch the pelicans fish, but today is different than the other days. Today Hadley no longer rests in a pouch on my chest, but walks beside me hand in hand.

I remind myself that the mushiness I feel at this moment, the sensation that some describe as sentimentality, also serves an evolutionary purpose. With that softening comes a fierceness, a fierce need to protect and aid and sacrifice. This is not a theoretical thing, but a biological one, rushing in my blood. In fact in the transformation borders the savage, and here too the pelicans have long served humans as a myth and symbol. "I am like a pelican of the wilderness," reads Psalm 102. At some point early Christians got it into their heads that pelicans fed their young with the blood from their own breasts, a mistake perhaps based on the red at the tip of some pelican bills, or, less plausibly, on the habit of pelicans of regurgitating their fishy meals for their young. Whatever the roots of this misapprehension, the birds became a symbol of both parental sacrifice and, on a grander scale, of Christ's sacrificial death. The images of pelicans as self-stabbing birds, turning on their own chests with their bills, were carved in stone and wood and still adorn churches all overEurope. Later, the parental symbol was sometimes flipped on its head, so that Lear, railing against his famous ingrate off-spring, calls them "Those pelican daughters."

* * *

The year culminates in a single day.

It is a day full of green, each tree and bird defined sharply as if with silver edges. I kiss my wife and Hadley goodbye while they are still asleep and head out at dawn to the road whereWalkerwill pick me up. Walker Golder is the deputy director of the North Carolina Audubon Society, a friend of a new friend, and today he takes me in a small outboard down to the barrier islands at the mouth of theCape Fear River. We bomb through a man-made canal called Snow's Cut, and I smile stupidly at the clarity of the colors: the blue water, the brown eroding banks, the green above.

We stop at four islands. In the course of three hours we watch Royal terns spiraling in their courtship dance, see week-old Ibises, and inspect the light blue eggs of a tri-colored heron. The southernmost of these small islands is filled with Ibises, 11,504 nests to be exact, and at one point we stand amid a snowy blizzard of Ibises, the vivid white birds with their flaming bills swirling around us. The southernmost of these is filled with ibis nests—11,504 to be exact. Ten percent ofNorth America's ibises begin their lives here, and at one point we stand amid a snowy blizzard of birds, vivid white plumage and flaming bills swirling around us. Next we visit an island of terns, the whole colony seemingly in an irritable mood. This island, and its nearby twin, were formed when the river was dredged in the '70s by the U.S. Army Core of Engineers, which used the sand to consciously aid Audubon in an attempt to create nesting grounds. Terns, like ibises and pelicans, require isolated breeding areas, preferably islands, and this human experiment, this marriage of birders and engineers, has worked to perfection.

The terns are impressive, but the highlight of the day, for me, isNorthPelicanIsland. Before this tiny island and its sisters were created, there were 100 nesting pairs of pelicans in the state ofNorth Carolina. Now there are 4,500. It is here that almost all of the pelicans that I watch back on my beach begin their lives. Hundreds of pelicans sit on their big ground nests, some of these nests as big as beanbag chairs. They watch impassively as we approach. The old naturalists might have called these birds "undemonstrative," but I'll go with "calm." In fact, while we're anthropomorphisizing, I might as well put "Buddha-like" in front of calm. It's hard not to project this on them after experiencing the wild defensiveness of the tern colony that we visited earlier. The pelicans barely glance up at us. Theirs is a much different survival strategy, and a much quieter one, natural for such a big bird with no native predators on these islands. I crunch up through the marsh elder and phragmites to a spot where two hundred or so pelicans are packed together, sitting on their nests, incubating. Behind them, in a beaten down red cedar, sit twenty egrets and few glossy Ibises. But the pelicans, quiet as they are, are the show. Some still have the rich chestnut patches on the backs of their heads and necks, a delightful chocolate brown: leftover breeding plumage. They sit in what I now recognize as their characteristic way, the swordlike bills tucked into the fronts of their long necks.

While the birds remain quiet and calm, there is an intensity to the place. This marsh island, like most of the islands that pelicans breed on, is too close to sea level to provide any sense of certainty. One moon-tide storm could wash over it and drown the season out. This is the year at its peak, at its most dangerous, a time of year marked by both wild hope and wild precariousness, danger and growth going hand in hand. It is a full season but it is also, of necessity, a defensive season. Maybe their ancient lineage allows the birds a greater confidence, an overall species confidence, but on the other hand there is an urgency for each individual bird, even if that urgency seems staid to us.

I'm not sure exactly what I gain from intertwining my own life with the lives of the animals I live near, but I enjoy it on purely physical level. Maybe I hope that some of this calm, this sense of ritual, will be contagious. If the pelicans look lugubrious, there effect on me is anything but. And so I indulge myself for a moment and let myself lift into a feeling of unity with the ancient birds. It may sound trite to say that we are all brothers and sisters, all united, but it is also simply and biologically true. DNA puts the lie to our myth of species' uniqueness, and you don't need a science degree to reach this conclusion. Montaigne, that great leveler of pomposity, said it best four hundred and fifty years ago when he wrote that even on the highest throne in the world we are still sitting on our asses. It's obvious really and there for anyone with eyes to see: We are animals, pure and simple. And when we pretend we are something more we become something worse.

Having seen these fragile nesting grounds a thousand times before,Walkeris to some extent habituated to them. He is also more responsible than any other human being for their protection. "We only visit briefly in the cool of morning," he explains, "so not to disturb the birds." Playing tour guide, he walks in closer to the nests and gestures for me to follow. He points to some eggs that look anything but lusterless, and then points to another nest where we see two birds, each just a day old. Though pelicans develop quickly, they are born helpless, featherless, and blind, completely dependent on their parents, their lives a wild gamble. Heat regulation,Walkerexplains, is a big factor in a nestling's survival. Pelican parents must shade their young on hot days, and one dog let loose on this island while the owner got out of his boat to take a leak could drive the parents from the nest, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of nestlings.

But we are not thinking about death, not right now. We are instead watching these tiny purple dinosaurs that could fit in the palm of your hand, the beginnings of their extravagant bills already in embryonic evidence. And then we see it. In the neighboring nest an egg trembles. Then a tapping, and a pipping out from within.

A small blind purple head emerges from the shell. "Something only a mother could love,"Walkersays, and we laugh. But we are both in awe. It is the beginning of something, any idiot can see that. But what may be harder to see is that it is also a great and epic continuation.

While we watch, the almost-pelican cracks through the eggshell, furious for life. Then it shakes off the bits of shell and steps out into a new and unknown world.

November 8, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: Be Your Own Willy! Give Yourself a Minimum Word Count

The self-discipline required for writing has always been at odds with my nature, which is fundamentally lazy. Right now, for example, I'm switching back and forth between this blank screen and Facebook Scrabble, and I'm also contemplating the guilty pleasure book that arrived from Amazon yesterday, A Year and Six Seconds by Isabel Gillies. It's just warm enough that with a sweater I could read in the hammock.

But in addition to this Bad Advice Wednesday that David asked me to do, I've got a novel to write, and it's not going to write itself. Not unless I do some typing. You might say that the novel won't write itself no matter what. But I've found that's not entirely true. When writing in the long form, it seems to me that my subconscious ends up doing most of the heavy lifting – as long as I give it a little kickstart, which I can manage no matter how unmotivated or uninspired I feel.

In one of my favorite novels, I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, two daughters lock their father – a dissipated writer – in a tower. The character, James Mortmain, a formerly successful author, has not written a word in years, and the family is in financial ruins. His daughters tell him they don't care if he writes "The cat sat on a mat" over and over again: just so long as he puts pen to paper. And that's exactly what Mortmain does. First in anger, he writes that sentence – the cat sat on a mat – over and over. Then, after a while, ideas start forming, and instead of anger he feels excited, until he finally emerges from the tower with a manuscript.

In concocting this scenario, Dodie Smith may have been inspired by the writer Collette, who wrote her first books – the Claudine novels – in a locked room. Her first husband, Henri Gauthier-Villars, would shut her in every day and not let her out until she'd produced an acceptable number of pages. The marriage didn't survive, but the novels (incidentally published under her husband's pen name, Willy) were a scandalous success.

My own husband has never locked me in a room, but he does something almost as effective. He shuts himself in a room and starts typing. The house where we live now is better insulated than some of the homes from our early days; I can no longer hear him clickclacking away on the keyboard while I'm lingering over my morning coffee. But I do know he's in his study, writing, and there's nothing like somebody else's industry – at the exact task you ought to be undertaking – to shame you into working.

Obviously shame is not the ideal motivator, especially when the ideas aren't crackling. But a less-than-ideal motivator is better than none at all, so here's what I do: I force myself to write a thousand words a day. If it takes me an hour, then I can stop. But if it takes me three hours, or five, or six (not counting occasional Scrabble moves), I still can't call it quits until those thousand words have been pounded out onto the page.

And it goes without saying that sometimes I end up with one thousand truly crappy, unusable words. Paragraphs that don't connect, threads that can never be sewn into the finished quilt. But without fail, once I've written those thousand words, something happens when I walk away from the computer. Ideas start to form. Sometimes these ideas will be about how to fix the mess I just made. More often they'll be about what's going to happen next – or what should have happened before. The act of forcing one thousand words brings my characters to life in my head, and once alive they start talking to me. Better than that, the story talks to me. It's as if I started a conversation, and my novel answers – often providing me with the catalyst for my next thousand words or more.

Sometimes, thankfully, there's no need to force it. Sometimes a novel has such a full grip on my imagination that any time away from working is almost physically painful. This past summer, writing a first draft, I hit one of those magical stretches of bona fide inspiration. I sat down and the words just flowed from my brain to my fingertips. I wrote fifty pages in four days, pages that I felt great about, and then, suddenly, I hit a wall. The story needed more time to germinate, and I thought about taking a break, just to think about where I'd go next.

But I didn't take a break. I sat down, and I pounded out a thousand words. It was a far cry from the previous days' work, but it gave me a jumping off point to sit down again the following day. And after a few painful days, the joyful and productive days returned.

So be your own Willy. Lock yourself in a room. Don't let yourself come out until you've produced something, anything. There's no need to think of it as forcing inspiration; it's more like inviting inspiration. You don't even have to ask nicely – just consistently. And sooner or later, inspiration will come.

November 6, 2011

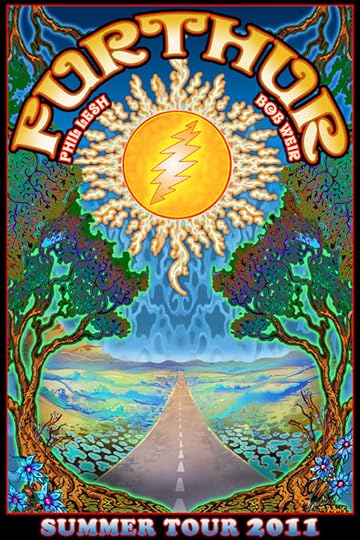

Furthur in Portland, Maine

Friday night, Juliet and I and a lot of other people from Farmington (we saw friends and familiar faces on the highway, we saw them in line, we saw them at the concert, we saw them in the parking garage after) drove down to Portland (our Portland, the one in Maine) to see the remnants of the Grateful Dead perform in their latest incarnation. Juliet's been following Furthur for a few years now. She collects tour posters, downloads concert recordings, buys t-shirts and tie-dyed trousers, travels all over the country making the "shows," as they're universally called, the focal point and excuse, really, for visits with friends and family.

Friday night, Juliet and I and a lot of other people from Farmington (we saw friends and familiar faces on the highway, we saw them in line, we saw them at the concert, we saw them in the parking garage after) drove down to Portland (our Portland, the one in Maine) to see the remnants of the Grateful Dead perform in their latest incarnation. Juliet's been following Furthur for a few years now. She collects tour posters, downloads concert recordings, buys t-shirts and tie-dyed trousers, travels all over the country making the "shows," as they're universally called, the focal point and excuse, really, for visits with friends and family.

#

I'd never been. My worry was that I'd miss Jerry too much. I've been told (by Juliet) to get over it. This is a new band. But they play the old songs! Is my argument. I was never quite a deadhead, though I liked them a lot. I was, though, and remain, a Jerry head. He was a true genius in several guises, and whatever he touched turned to genius, too, including the Dead. He was also very funny and lighthearted and a drug addict who died young of exhaustion and diabetes.

We got to Portland early and found there was no line, just a few bleary guys sitting in sleeping bags, surprised to find themselves alone on the pavement. No one wanted to wait out in the cold, and most must have known the venue was forgiving, open floor, general admission. This made me happy, as rather than sit out in the cold we crossed the street to a sports bar that could have been in any city in America, especially Denver, but not really Portland. Sports were on the TVs, but Jerry was on the sound system. And among the happy-hour crowd were plenty of pony-tailed relics like me, also the new crowd, tie dye bridging the generations.

I never understood how anyone could trip in public. LSD, I mean. Forty years ago, the last time I was interested, I'd plan such adventures meticulously so as not to run into parents or cops or any kind of trouble at all. At the bar beside us was a young couple from Canada, he said. They just kept gazing. "You okay?" I said. "Where is this?" the fellow said.

Both of them could have been at any bar in Ithaca in 1971. But then again, where was that?

Juliet had made burritos for us, and we had a bite or two at the bar in case they were confiscated at the Civic Center doors.

They were indeed confiscated, an efficient little cop feeling Juliet's big coat till every trace of food was gone.

Inside, the place was empty. Cumberland County Civic Center, to use the full name. We walked up to the stage, put our hands on it, could have stayed there. The floor was entirely empty. We picked seats at the back of the hall behind the sound board, where Juliet has learned the sound is best. The place began to fill up.

The Civic Center is a cement shell, one of those buildings built on a tight, tight budget, no frills, no extra cement, even the restrooms packed tight with urinals (and not enough of them), the passageways too small, a claustrophobic feel altogether, architects erasing all but the last necessary lines with each budget squeeze.

And the food, disastrously terrible. You could not make worse pizza if you tried. Okay, maybe dogshit and plaster would make a worse pizza. But not by much. And that was my dinner in that beautiful town with some of the greatest restaurants in the country. How did food get to be such an afterthought in this country of plenty? Actually, I think I know the answer (radical corporatism), but that's a discussion for later. Next show, if Juliet can get me to go, we're doing what it seems everyone else did–eat dinner somewhere nice, relax, not worry about being first in the doors.

Our friend Jan arrived beaming and found us. Let's go look at the stage, he said. He's been to dozens of shows and he really followed the Dead and he's full of facts and memories about them. We were both at Watkins Glen, 1973. We talked about that and made our way onto the covered ice rink and maybe three quarters of the way down the floor, the crowd thickening as we went, Juliet in the lady's room.

forgot my glasses

Then the lights dimmed. The crowd pressed in, but not too tight, not yet, no patchouli, mostly Shalimar. Everyone friendly. Ages diverse: I wasn't the oldest, I wasn't the youngest. The mean was probably mid-thirties, and that's what I found when I looked inside myself, mid-thirties and getting younger.

I texted Jules. She texted back. She'd try to find us. She was 20 when we met in 1982. Jan had a white hat. I was 29. No one else had a white hat, but rainbows and Cat in the Hat hats. Pot smoke filled the air. Cigarette smoke, too. But pot smoke, thick.

I felt kind of good.

Phil came out at a satisfied saunter. He's the other genius of the old Dead. He wrote a terrific memoir called Searching for the Sound that I listened to him read on tape. He has a pleasing speaking voice. The book ends just after his liver transplant. It's the most unflinching of celebrity memoirs. Things were not always peaceful with the Dead. He tells it all. It's the history of an era, and there he is, living history. He was trumpet player in the high-school band and Jerry befriended him and they hung out and Jerry told him he was going to be their bass player, and that's what he became, fairly simple guy suddenly an acid-head then a rock star, a guy with a level head and a nerd's interest in getting everything out of his equipment, inventing a new bass, six strings and a range down into the sub-basements of rock.

He looks peaceful now. The whole band is clean now. Chem free.

Bob Weir strode out off balance like his mustache was going slightly faster than he was and he had to struggle to keep up. A truly prodigious huge mustache, capable of great speed. A guy behind me said Bob looked like a Hindu mystic, and it was true. He looked, in fact, very much like a guy I'd seen a photo of that morning, a 100-year-old Hindu man who'd just finished a marathon and got himself in the Guinness Book of Records. That is to say, Bob Weir looked like a 100-year-old Hindu man who'd just finished a marathon.

listening

The music was good. I enjoyed being up close. I watched JK, the new guitarist, minutely. He was the guitarist in Dark Star, which is the best of the many Dead tribute bands out there, playing whole Dead shows nearly note for note and certainly song for song. JK was so good at being Jerry that Furthur hired him to play the part, more or less. He has a bouncy presence and plucks upward at his axe to get those chords out, rising on his toes.

He's very good, but he's not Jerry.

And I did feel sad.

I'm someone who cried when Jerry died, and I can't seem to let go.

I liked the light show. Pot wafted past, and more pot, forest fires of smoke. I felt sad but kind of good and danced and looked around me at all the people. A pretty girl grinned at me, not as of yore, but as she no doubt grins when her grandpa sings out "Riding that train! High on cocaine! Anyway, she grinned and I felt even sadder and even kind of gooder and the pot smoke was dense and I grinned and doubled my dance step. Maybe she was grinning at someone behind me. I felt very self-conscious, and very much like I'd like to be onstage. The crowd grew denser. A sweaty man too high to dance danced into the space in front of me, once my space, and smelled bad and danced.

Jan swayed beside me, very content. At one point he turned to me and offered gum, which I took. Gum tastes really good, I thought. And I kept thinking that. "Save the wrapper for later when you want to spit it out," he said helpfully. We've both got kids.

Juliet never found us, so before the last song of the set I worked my way all the way back and found her in our seats. She'd worked her way up probably past us and got close to the stage but never saw us, gave up and retreated. Phil's low-low notes thump her chest disagreeably. I like that thump, like fireworks finales all in a row.

Second set Juliet and I sat together, a proper date, and watched from way back in the back. It did sound good back there. I was happy to sit. I liked the light show. I couldn't see much but the colored beams limned in smoke, as I'd forgotten my long-distance glasses.

Furthur! They played a whole suite of songs from the seventies, lots of the material from the album Live Dead, c. 1969. I had never cared for the Dead till I found that album in 1971, a new freshman in college. I tried not to like the album at first–the Dead just did not fit into my eighteen year old's narrow world view–but I was in a band that learned and performed the whole St. Stephen, The Eleven, Love Light sequence, and in the learning had come respect. Respect for Jerry mostly.

And Europe 72! That's a great album, a tour de force. The boys at their peak, I think.

But back to 2011. I liked the concert, hated the venue, and felt sad but also kind of good. My wife and I were the old couple who sat and swayed and held hands. I felt a little like I'd been forced to move back into a house I'd lived in forty years before. The place had been remodeled on a budget, and though much was familiar, the neighborhood just wasn't the same, the girlfriend dead, my own body in decline; also, I've had better houses since, but being back in the old one, ev en if just for a little while, seems to have put a fresh experience on top of memory and the fresh experience is shielding me from memory and maybe I'm a notch less sad. The last encore of the evening was "Touch of Gray."

en if just for a little while, seems to have put a fresh experience on top of memory and the fresh experience is shielding me from memory and maybe I'm a notch less sad. The last encore of the evening was "Touch of Gray."

Next morning a walk on the beach and cliffs in bright November sun slanted low across the swells and making a road of sparkles you could walk on, just as if it has always been that way, and I guess in fact it has….

November 3, 2011

Random Doodle Day: Sketches From My Journal

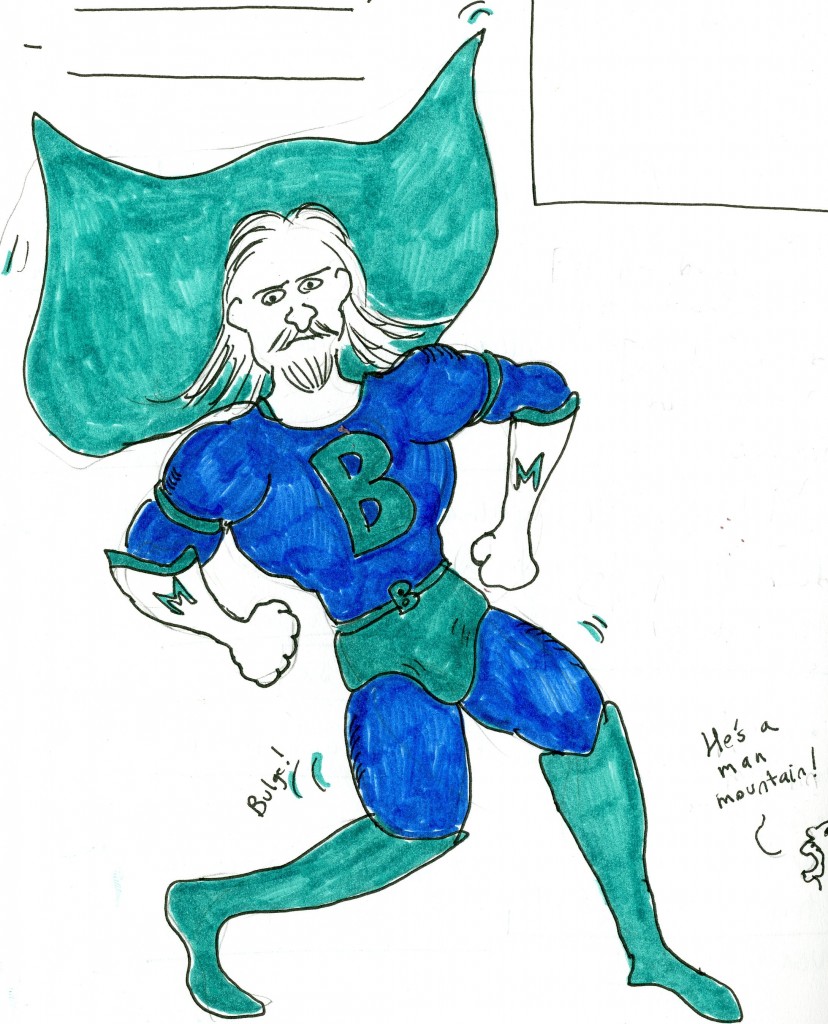

After some consultation with my blog-mate, I have decided to upgrade the drawing of Super Bill, aka Captain Memoir. I don't feel the earlier drawings captured his true super-ness.

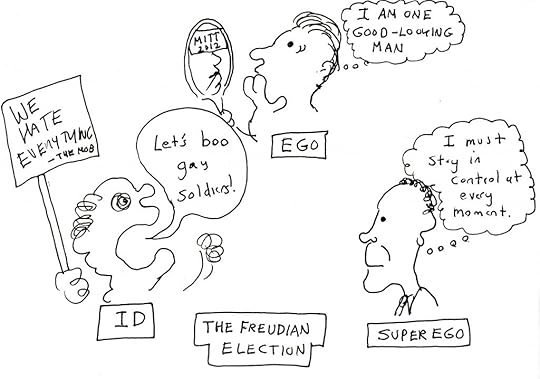

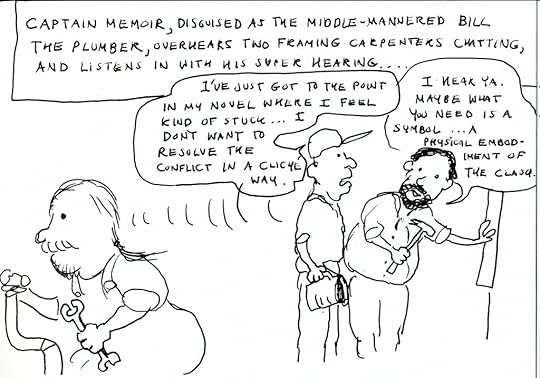

This is from the graphic novel, Wormtown, that I abandoned….

November 1, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: The Annotated Table of Contents

Table of Contents for "100 Famous Views of Edo"

Let's say you have an idea for a nonfiction book, whether it's a memoir, an extended personal essay, journalism, or something else. It's hard to get started, isn't it? Or if easy enough to get started, hard to keep going. Part of the problem is knowing where to start, and after that, where to go.

.

Or you've finished a draft of a book and the chaptering came willy-nilly as you composed. There are holes in the narrative or in the stream of argument. The sections are of all sizes and methods and shapes. There's no sense of progression, or if there is, the progression seems to stutter.

.

Or say you've written four essays on a related theme. Growing up in Nigeria, for example. Or your life as a teacher and coach. Or in my case, more than 20 years ago, on my adventures in nature with my then girlfriend (now wife) Juliet.

.

Or take it a little further–you've thought quite a bit on your subject and have some preliminary chapters put together and you want to go ahead and pitch your book idea to editors or agents.

.

Or back up a little: You haven't written much at all, but you'd like to explore the possibility of writing a book on your subject of choice.

.

In each case and many others I advocate the annotated table of contents. It's a simple thing. You give your book idea a title, if it hasn't already got one, and then you decide arbitrarily on a number of chapters. Ten or fifteen or twenty–doesn't matter. Then you make yourself a table of contents, each chapter with a title of its own followed by a two-or-three line description.

One exercise I give to writers who haven't written much is to think what book they might write in an ideal world, one in which they had all the time and money and talent and skills they needed. What would be in chapter one?

Sometimes you can't quite answer that, but you know that such-and-such an event or idea must be in the middle. So start there: Chapter 7: We begin to breed dalmations. And fill in the annotation (which amounts to a descripton of the contents of that fantasy chapter), as best you can, several sentences or more. Chapter 7 should begin to suggest what should be in chapters 6 and 8. So fill those in a little, too.

If you're the one with the four related essays–declare them chapters. Where would they each fit in the greater story that links them? What chapters are missing, and what would be in them? Your lines of annotation might grow to include research notes, and maybe passages and portions of what you will eventually write–sometimes, the annotations can grow into chapters, practically on their own.

If you're ready to try a book proposal on editors or agents, an annotated table of contents is a very helpful item to include. Your writing samples will prove your skills, and your pitch will lay out the nub of your idea, but the table of contents will illustrate the shape of the proposed project, make it possible for potential supporters to picture it whole.

My first book, Summers with Juliet, came about because my friend Betsy Lerner (who at the time was an editor and is now my agent), read four seemingly unrelated essays I'd written in grad school and noticed that all four had to do with a life in nature, and further, that all of them involved Juliet, something a little different. Betsy suggested I put together a table of contents. The pieces I'd written all fell into the middle of the portrait of a future book that emerged. I'd met Juliet in the summer, so that must be chapter one. We'd gotten married in the summer, eight years later, so that must be the last chapter. I let chronology rule, and filled in the blank spots with chapters that filled in what was missing, this summer, then that.

Always, the best thing to do is start writing. The annotated table of contents can help. The next thing is to keep going: pick a chapter that's gone unwritten, and get to work.

Our Big Year

ABOVE: JACK BLACK, OWEN WILSON, AND STEVE MARTIN IN THE BIG YEAR

I think the reason that I watch birds instead of birdwatch is that I'm reluctant to turn the woods into an arena. I'm already competitive enough in too many areas of my life. I don't really mind if I'm a bad birder. Just as long as I get to see birds.

This was the problem I had with the book, The Big Year, though as you'll see below from the review I wrote for the Christian Science Monitor, I liked it well enough.

The photo at the right is obviously a joke, reused from our Jonathan Franzen and the Great Swamp Warbler post. You will note that both Jack Black and Owen Wilson have aged considerably, while Steve Martin looks a lot younger.

These strange birds reduce nature to items on a to-do list

by David Gessner

Originally published in The Christian Science Monitor

Anyone who has ever spent any time with birders – not bird-watchers but honest-to-God, hypercompetitive, able in a glance to tell a Bachman's sparrow from a Botteri's birders – knows that they are as worthy of study as the birds they watch.

With notable field marks (the craned necks, the straining eyes) and clear behavioral patterns (creeping through the brush and scanning the sky), they are fairly easy to distinguish from other homo sapiens. The quirkiness and obsessiveness of this subspecies make them an interesting and fairly obvious subject for chronicling, and Mark Obmascik's new book, "The Big Year," is one of several recent attempts to tell the stories of this strange tribe.

Obmascik follows the lives of three men as they each attempt to break the single-year record for sighting the most bird species in North America. In birding circles, such attempts are known as "The Big Year."

These men, most notably a loud-mouthed New Jersey roofer named Sandy Komito, are the furthest thing from nature-lovers, and to a certain extent the birds themselves are incidental. What they're really playing is a numbers game. They fly all over the country at a moment's notice searching for rarities, rushing to the Rockies for a glimpse of a ptarmigan or to the Rio Grande for a look at a clay-colored robin.

Moments of actual awe and wonder, versus moments of competitive zeal, are few and far between, and one wishes that Obmascik had gone back in a later draft and added these once he realized just how joyless this enterprise is. Their pleasure seems akin to checking items off a things-to-do list.

They abhor anything that gets in the way of their single goal. When Komito's charter boat stops to watch a pod of gray whales, he bawls out the boat's owner, snapping, "Let's stop the whale nonsense right now."

But obsessives make interesting characters, and this is a vastly readable book told in lively journalistic prose. We are pulled along, following Komito and his two closest competitors, as they battle their way through the year, worrying endlessly about finding enough birds and about how the other guys are doing. As their numbers rise and the year deepens, their lives attain the simplicity of a quest, like monks with frequent flier miles.

Along the way, Obmascik threads in bits of birding history, particularly the oft-told story of Audubon and the less-told one of Roger Tory Peterson. It was Peterson who accidentally kicked off the whole notion of a "Big Year," when he mentioned having seen 572 species in 1953.

It's telling that Peterson dropped that number in a footnote in his book "Wild America," and it would have been interesting to see Obmascik attempt to contrast Peterson's love of birding to the fanatical obsession with numbers among this sub-sect of his followers. But instead of analysis, Obmascik favors the literary equivalent of a car chase: It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World With Birds.

For the most part, Obmascik is light on his feet, telling his interesting tale with journalistic sureness, but when he strains to be funny, he treads heavily. He can't resist the big Ba-dum-da one-liner, and he goes out of his way, even breaking his fine overall flow, to crack whoopie-cushion Jokes with a capital J.

One of Komito's competitors plagued by seasickness is dubbed the "Dukes of Hurl," and Obmascik notes, "It's not easy being green." A man with a poor sense of smell has a "hapless honker," and someone who needs to urinate is doing the "wiggly gotta-pee jig."

This is closer to Sinbad or Carrottop than Bryson, and the jokes sometimes have a bumper sticker feel – "Chicks Happen," or "His plastic went spastic" – that undermines the overall quality of the prose.

An example of that quality comes in a beautiful description of the sea life off the coast of Monterey or in his description of Harlequin Ducks. The book would have benefited from more lingering descriptions like these of the natural world that birders, like it or not, often find themselves in.

It was just this quality that elevated "Birders" (2002), Mark Cocker's book on birding obsessives, which was a kind of BBC version of "The Big Year." Obmascik chooses instead to dwell on the antics and adventures of his wacky crew. In doing so, he has managed to produce a very readable field guide to a strange and obsessive flock.

But he also misses some opportunities, and leaves us wondering why these men are collecting birds instead of coins or stamps.

• David Gessner is the author of 'Return of the Osprey: A Season of Flight and Wonder' (Algonquin Books).

October 30, 2011

What Bloody Man is That? (a review of "Sleep no More")

We were a little late, leapt out of the cab on 10th Avenue, nothing to see on West 27th street toward the river but a couple of closed galleries north and a wall of blank warehouse faces south, pair of huge men hanging out a little ominously under a bare bulb down there. But that doorway—there was a ten-foot star above it, nothing flashy, flat-black as the building in fact, was clearly a clue, the first in an evening of clues and little resolution. We asked the men where the MacBeth performance was, if they knew where it might be. They looked at one another long. The huger one brightened very slightly. "You mean the Hotel?" he intoned. "The Hotel McKittrick?" Behind him the doors opened. A nattily dressed and fake-ish hotelman eyed us, said, "You're not too late. But hurry. Drop your coats at the check."

We were a little late, leapt out of the cab on 10th Avenue, nothing to see on West 27th street toward the river but a couple of closed galleries north and a wall of blank warehouse faces south, pair of huge men hanging out a little ominously under a bare bulb down there. But that doorway—there was a ten-foot star above it, nothing flashy, flat-black as the building in fact, was clearly a clue, the first in an evening of clues and little resolution. We asked the men where the MacBeth performance was, if they knew where it might be. They looked at one another long. The huger one brightened very slightly. "You mean the Hotel?" he intoned. "The Hotel McKittrick?" Behind him the doors opened. A nattily dressed and fake-ish hotelman eyed us, said, "You're not too late. But hurry. Drop your coats at the check."

The hallway in front of us was long and as flat black as the face of the building. The coat-check people were friendly but from another era, maybe the thirties. We were given no playbill or papers at all, nothing to go on but what we'd heard, and I'd limited my research so as to be open to surprise if not confusion. At the front desk (or "front desk," a prop), there was some muttering about our tardiness, but we were given our tickets and directed to another door. "It's your lucky night," a film noir hostess said to me. Then to my friend, "You, not so lucky."

Our tickets were taken by a man in livery and we were shushed at each turn in the hallway and each landing on several flights of stars, eyed at each set of black curtains by more actors. You began to realize. Young actors playing the roles of opprobrius hotel people, with more and less intimidating effect, some imperturbable as Beefeaters, others more gracious, small roles for amounted to a chorus.

We emerged into a barroom, or, once again, "barroom," a set, but with a real bar, where we were served a real drink each and given a real bill for $27.00. A little jazz quartet was swinging away—good musicians, too—and we found a table, not difficult as the rest of the audience seemed to be leaving. Everything flat black and a little cobwebby and like you'd stepped into a time machine and emerged in Chicago, 1932, a speakeasy. The singer, an ebullient African-American woman in period dress, came to the table, said we'd best hurry along—drinks couldn't go inside. I reluctantly chugged my Manhattan and we joined the line moving through yet another black curtain, last people in. At a podium we were given hard-plastic Freddy Krueger masks with long, protruding chins and exhorted to put them on, keep them on.

I'd been expecting MacBeth.

I really wanted to see MacBeth.

[image error]

Entering the McKittrick Hotel

The witches stirring their caldron, predicting he'd be made King, predicting he'd be killed, too. And Lady MacBeth, taken with the news, convincing him to kill the actual king, Duncan, and then mayhem from there forward, Malcolm sussing things out. Lady MacBeth growing mad: "Out, out, damn spot!"

But this was a dimly lit and fussy installation (of some fascination, I admit).

We found a room full of taxidermy animals and skeletons—a beaver, I think, though there may have been some skeletal tinkering.

We came to a large room with a platform in the middle and a stuffed grizzly with a stuffed rat in its mouth, and suddenly here came what was certainly an actress, she followed by an actor. They weren't happy, these people. The man seemed to be in his twenties. The woman a little older. Soon, inexplicably, he was naked. She pushed her way through the masked crowd and fell into a rocker. He kept up his silent, naked imprecations. I noticed his balls were shaved and his dick a touch tumid—none of the shrinkage you'd expect. They must have a warm dressing room or someone to fluff him or perhaps he fluffed himself—you'd definitely want to put your best dick forward going out among all those masks without a thing to say.

Some of the people in the audience wanted to stand really close to this kid, some closer yet. Among them, you could pick out all kinds of types despite the masks. I had a distinct feeling the group standing in the way of my view were from Maryland, I couldn't say why. Another group might have been Baptists; anyway, they were excited at this chance for anonymous voyeurism and vicarious sin. There was a kind of bubbling, also a feeling of nice people trying to figure out what on earth kind of experience they were having.

I'm not as nice as some of those folks were, but along with them I was baffled. If that was MacBeth, he was too young. And why was he naked? Was it someone else? Banquo? I didn't remember Banquo being naked, either. Duncan? And, whoever he was, why wasn't he saying anything? And why was he in a hotel rather than a castle? And why was it 1930, and where was Humphrey Bogart?

Honestly, it could have been an Edgar Allen Poe story or a Raymond Chandler novel with no changes of any kind and the confusion in my breast would have been no less.

#

The production, an imaginative and actually obsessive recreation of Shakespeare's bloody MacBeth, is called "Sleep no More," after a line in the play. The British theater company Punch Drunk, flush no doubt from five sold-out months of the show in Boston, spent several millions converting three adjacent six-story warehouse buildings in Chelsea into this set, the conceit being that it was a hotel, basically an elaborate haunted house, but no screaming. Apparently, a couple of hundred volunteers helped decorate the place. 100 rooms, each more creepy than the last, including a darkroom with photos hanging to dry—really grotesque murder-scene photos, a little vague but effective. You could open the drawers on desks and open notebooks and reach into coffins. Nothing was accidental, everything had been placed. Lines from MacBeth were written willy-nilly on scraps of paper and stair railings and all over the walls in a small chalk script everywhere. We wandered, climbed stairs, walked dark hallways, happened upon maybe 50 of the rooms, maybe as few as 30–I didn't count, but had the distinct feeling of missing things.

I liked the show best when I could find the play.

We chanced to be standing in a room with bathtubs when Lady MacBeth came running in pursued by stagehands in black masks, audience members in white masks, and by her demons, as invented by the Bard. There was one bathtub with pink water in it (I hoped warm) and she sat right in and tried to get that sin washed off. She had very pretty breasts and a great figure altogether and one of the masked audience guys was leaning in awfully close. But she didn't say anything, not a single iamb, had to rely on some pretty fancy mime to get her anguish across, also splashing.

Then she got up (taking a hand from the close-observer audience guy, who may, come to think of it, have been a plant), stood there kind of emotionally, and trotted away, everyone following. Not me. My impulse was to get away from the crowd. I can only compare it to my brief experience of the Hellfire Club in the Meat District, which was under the street next to my building when I lived there, contiguous with our basement. I'll have to write more on this another time, but suffice it to say that as a neighbor I had a free pass and decided to have a look one night. The hellfire was a hetero S/M club and people were down there in leather and more leather and a certain amount of latex and, like, whips and chains and this and that, a lot of naked men and flaccid penises and black socks and just a few women, some guided by what appeared to be their lesbian keepers, paraded into sexual acts on platforms with all comers, so to speak, and followed in every step by a crowd of gawking onlookers. If only they'd called it MacBeth I might have stayed more than half-an-hour.

Anyway: more rooms.

A cool room lit bluish with a forest made of real trees. This stumpage must have been logged in the last three-to-five years as it was a single-species regrowth with trunk diameters under two inches. Said the critic from Maine.

A barroom with a bar made of cardboard boxes, pretty cool, startlingly heavy and stable—cement filled, I decided. Bits of the play written on wine labels. A little breather, till, oh-no, here came two guys who really should have been studying for their mid-terms, no idea who they were supposed to be playing. They drank a lot and banged the wine bottles down in anger. They stewed and fumed and then they danced, rolling across the billiards table in one another's arms, a stagy pas-de-deux that did not resemble a fight, but that was okay, as they made friends afterward. I don't know what characters they were meant to be.

A room with beds, one of the beds covered in gore. We passed through this room several times, the last finding an actor and his entourage there, which, sadly, seemed to me to be my cue to leave.

A detective kept running through. I think he must have been meant to be Malcolm. He looked vexed.

A bathroom, finally. I'd had to pee for an hour. Or fifteen minutes. Or half a day. Very unclear how much time had elapsed. A relief to be in a room with no cobwebs, though the lights were dim.

Another barroom, much like the barroom where my credit card was still being held, but with no liquor, just (finally) some witches. They didn't get to say anything, but they got to writhe a great deal and be naked again. Quite a bit of torment, and all these spectators, also a baby in a tub of red jello and red sugar-paste, very disturbing, Duncan's baby, no doubt, and honestly, pandemonium. One which was of Asian heritage, lovely and convincing, one was of African heritage, ditto, another was a man. The weird sisters indeed! I leaned on a sticky pillar and just thought it was very much time to go. The yard-sale tableaux were losing their fascination. The actors had far too much to achieve within the chaos.

Our sense of direction was whacked, however, and we kept coming back to the same place, that room with the baby in strawberry jello. You'd go up flights of stairs and walk for seeming miles and through rooms familiar and unfamiliar and open a door and you'd be back with the baby in jello, uncanny, crossing paths the whole time with this or that young member of the troupe and his entourage of masked viewers. And always that detective, looking right through you. I could have told him exactly what had happened. Much of what he needed, in fact, was written on the walls.

I found that if I took my (hot, uncomfortable) mask off and held it behind my back and leaned provocatively against a railing or tub or whatever was available that a crowd would gather instantly to stare at me. Finally! They seemed to think, This must be Duncan. Anyway, unlike all the other actors he's old enough!

But quickly I'd be busted by one of the black-mask attendant people.

Idea: go to a Halloween store, get one of those black masks and smuggle it in, stand by a curtain and give the people from Maryland false advice in an ominous whisper: "Ladies and gentlemen, the players would be more comfortable if you'd all take off your pants and underpants for the remainder of the performance. And men, try to keep a little blood in your penises."

You know?

We stumbled into a large room with a banquet table and more of the audience that we'd seen at any one time–a large crowd. Duncan's ghost was bothering the proceedings, and it actually was a good moment of theater, all those characters in a line, ready to say their lines. But no.

The evening seemed to be coming to a head. I knew this meant leaving in a crowd of masks, no fun.

So I screwed up my nerve and asked one of the attendants how to get back to the bar and she couldn't have been nicer, solicitous, in fact, like she was worried I was too terrified to go on. And soon we were back in the bar and the singer was singing and it was all so fake and false except the credit card receipt, which I duly signed. But of course the hotel McKittrick was supposed to be fake and false. That was not the problem.

The problem was I had wanted more MacBeth.

I guess the Roman Polanski version (1971) will have to do, Netflix.

October 26, 2011

Bad Advice Wed: Accept Your Small Self; Strive to be Larger

I had every reason to be happy when I heard that Edith Pearlman had been nominated for the National Book Award. When my wife called to tell me the news she certainly expected to be happy. I am happy for Edith now, very happy, and I should have been happy for her then. After all, I had been lucky enough to be in the room when Emily Smith and Ben George, the founders of Lookout Books, had called to read Edith the glowing cover review of her book in The New York Times. That had been a thrilling moment, and we were on lifted up in its excitement, and news that she had now been nominated for the NBR should have provided me with a similar lift.

I had every reason to be happy when I heard that Edith Pearlman had been nominated for the National Book Award. When my wife called to tell me the news she certainly expected to be happy. I am happy for Edith now, very happy, and I should have been happy for her then. After all, I had been lucky enough to be in the room when Emily Smith and Ben George, the founders of Lookout Books, had called to read Edith the glowing cover review of her book in The New York Times. That had been a thrilling moment, and we were on lifted up in its excitement, and news that she had now been nominated for the NBR should have provided me with a similar lift.

It did not. You see I had secret hopes of being nominated myself. Maybe you did too? For my part I had written a book the Gulf Oil disaster which was really, I hoped, about much more than that disaster, about the way we will all be living soon, about certain choices we will all be making, about sacrifice, about what we are getting and what we must give up. And in writing about these subjects I had made formal writing choices that I had not seen anyone esle making: jumping from comedy to investigative reporting to essay to nature writing to farce. I understood why certain corporate swine—the publishers of big newspapers and magazines—would not give the book its due, but I dreamed (vaingloriously no doubt) that judges—fellow writers!—would see what I had attempted to do. And so when my wife called to tell me what had happened to Edith I could only focus on what hadn't happened to me. At the very least I should have thought immediately of my colleagues, my friends—Ben and Emily—and what this meant to them. The word was that the students up in the pub lab where Edith's book was created had let out a spontaneous cheer when they heard the news. I did not cheer. Instead, I was briefly, crestfallen.

But briefly. Only briefly. Which may just be the key, or at least a key, to the writing life. Let the ugliness pass; let the bile out; and something better may surface. You cannot expect yourself to be better than human and petulance is a human emotion. If you do expect yourself to be better you will only add more pain, in the form of self-flagellation, to the mix. There is a sort of knowledge (you might even be tempted top call it "wisdom" with your tongue only slightly in your cheek) in knowing that petty feelings fade. It is a modern fallacy to think that our smallest feelings are our truest, our most "honest." This is nonsense that, as my friend Sam Johnson might put it, must be refuted. Our moods move through us like the weather, and petulance is a brief thunderburst, not even a full storm. It no more represents our whole self than the mood equivalent an Indian summer day like this one in Boston. The trick, if there is a trick, is to let the weather pass through you and not call it your all. The trick is to wait it out, and not do anything stupid or mean in the meantime.

And then, once the small mood has passed, you can see it for what it was. See how small it was. See it within a larger context, and react more fully. An hour after Nina's phone call and I was already feeling happy and proud for Edith. Edith, a woman by the way who had worked devotedly and brilliantly at her craft for many years without getting the recognition she deserved. And if I was happy for Edith, I was thrilled for Ben and Emily, who were being rewarded for not just their talents but for a year of monumentally hard work.

Some might call this second emotion "phony." Some might say I was pasting an old school morality over my real first feelings. I wasn't. Not only wasn't this the case but I'm not sure I'd like to live on an earth, or in a body, where it was. And while we are refuting one modern cliché let's refute another. That trying, that effort, has little to do with any of this. "Largeness is a lifelong matter," wrote Stegner. Hear, hear. (Or is it here, here?) We must strive not to be petty. We must understand that we are all in the same (very leaky) boat. And that everybody's boat capsizes in the end.

Acceptance. And effort.