David Gessner's Blog, page 94

February 10, 2012

Movie Night: "Pina: A Movie for Pina Bausch"

#

I've just come from the beautiful new Film Society theater at Lincoln Center, where I saw Pina: A Film for Pina Bausch, made by Wim Wenders, a genius on the subject of a genius with a cast of geniuses, and I'm not kidding. The movie is in 3D and it's the best use of the recently revolutionized medium I've seen yet, stage spaces taking on form and outdoor spaces vastness incomparable. The film as conceived wasn't meant to be one but became a memorial to the great German dancer and choreographer (also actress, in at least on Fellini movie), who died five days after diagnosis with an unannounced cancer (the film never mentions it at all), two days before filming was slated to begin. This mortal coil. The cast is entirely dancers. The action is entirely dance. The sense of humor is sublime. The sense of depth and poignant homage is more so. The freedom of these dancers is dazzling. The invention is in large part Pina's and made possible by Pina.

"Keep Searching," is the only advice she gave one of the dancers. "Get crazier," another. "Dance for love," a third. Wenders has interviewed the company, but their words, off the cuff and eloquent, aren't offered in the usual interview format. Instead, the international cast (it's a large one) sit for the camera in gorgeous closeups while apparently listening to their own words, reacting naturally as they hear what they had to say, often with smiles. It's very effective, dancers using their bodies to express deep feelings. Someone should have thought of that before.

And the dancing is wonderful, very much the heart of things, often in water, often outdoors, sometimes in dirt, on grass, under a monorail, then inside it, and onstage in front of an audience shot so that we feel part of it, gorgeous sets. I laughed a lot. I watched very closely. I considered the human form. It's a fine movie, big time.

[If you like this post, Like it above--this is how our work finds its way in the electronic vast. If you like Bill and Dave's, Like the site. We do. Oh--and follow us on Twitter: @billroorbach @BDsCocktailHour]

February 7, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday: The Thisness of a That

My mind at work

Metaphor is the elemental condition of language. English teachers forever have been saying, "A simile is a comparison using like or as, and a metaphor is a comparison not using like or as." That's simple and plain, but it's not quite right. I'll buy the old definition for a simile, but a metaphor—wow!—a metaphor is something enormously greater than allowed for by Mr. Bottomlifter back in ninth grade. First of all, a simile is just a kind of metaphor. A symbol is a kind of metaphor (and curiously, something more as well: the thing itself). An analogy is a kind of metaphor.

Metaphor is big, and gets bigger the more you think about it. Metaphor, in fact, is the source of all meaning.

Yes, metaphor is a comparison. But that's saying a lot, given that comparison is the basic gesture of the human mind: closer, farther; lighter, darker; bigger, smaller; safe, dangerous; then, now. The extension of such elemental, dichotomous comparisons is the foundation of language, which in turn is the foundation of thought.

And the soul of clichés.

A steel trap is one of those devices used in cartoons to capture Elmer Fudd and in life to capture fur-bearing animals. A steel trap is a pair of tempered-steel crescents joined by a powerful spring triggered by a round plate of steel. When an animal steps on this plate—wham—his leg is caught, often broken, awful. The trap is staked to the ground at the end of a stout chain so a captured animal can't wander off.

Okay. A mind like a steel trap. What's the metaphor here? Let's see. You're so smart you hold on to an idea while it thrashes around and finally chews its leg off to escape, leaving you with only the leg of an idea and a bloody legacy of brutality? Or, as the comedian Steven Wright says, "I've got a mind like a steel trap: rusty and illegal in thirty-seven states."

It's fun to extend the comparison—the metaphor—as far as you can, to the very absurd edges of correlation. If your mind is like a steel trap, what is the spring? What is the steel plate that triggers the release mechanism? If animals are ideas and minds are traps, do minds destroy ideas? Do ideas have lives separate from minds? Do ideas roam the wilderness? What are the furs of ideas? And tell me this: Who is the trapper running the trap line? What's the chain? What's the stake?

Here's a little Wallace Stevens.

I was of three minds

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

#

Consider those troublesome analogies on the SAT test. You know, x is to y as xx is to yy. Here, let's do one. Fill in the blank: train is to track as airplane is to _____.

Most would say sky.

Each element of an analogy is called an analog. In the above example, train is the analog for airplane, track is the analog for sky. All are comparisons not using like or as, by the way, and certainly metaphorical. And in this example (as in most), seriously magical. Think of it: our minds easily and completely accept the idea that dense, heavy bars of extruded steel manufactured by humans are similar to—analogous to—the sky. Which is air.

Kenneth Burke, in his challenging book A Grammar of Motives, says that metaphor "brings out the thisness of a that." Aristotle speaks of the way metaphor helps us understand the unknown or slightly known by comparing it to what's known.

Stop signs are metaphors in that they are symbols. Symbols are objects, generally, and are themselves, but also stand in for something, mean something else, something greater than themselves and not always inherent in themselves. We've come to agree that a red octagon (my father claims they used to be yellow) with the following white shapes on it—S, T, O, P—will mean something particular. In practical terms, it means law-abiding types will put right feet on brake pedals till the motion of their vehicles is entirely arrested. The sign is a command to make your vehicle's status an analog for a word meaning, a meaning that is itself an analog for a condition in nature—stoppedness. But the sign is also something real: a piece of metal or wood on a stick or on the wall in a college dorm room. (Put it back, dudes!) It's a non-literary symbol in that it is precise, stands for one thing only: stop.

The Nike swoosh is a symbol in the same way. The swoosh isn't the company. The swoosh isn't a sneaker. The swoosh merely invites us to consider the company, to compare the swoosh to what we know of the company. Swoosh does not equal Nike; swoosh only represents Nike, and this representation is a form of metaphorical comparison. But the swoosh is not as much of a thing as a stop sign or a duck is. I mean, yes, it does have reality in that sometimes it's a grouping of threads, or a thin layer of ink, or a gathering of pixels on TV. But that's not much reality, less than you and I have even on our worst days. Still, it's a symbol, moving toward the literary, as it can mean more than Nike, can stand for a life devoted to sport, for example, or for the money exchanged in an endorsement deal.

Most words are symbols, most language metaphorical. (Or, actually, if you believe Jacques Derrida, all words are metaphorical. It would take a PhD in English to explain, and I happen to have one right here—Jennifer Cognard-Black, who was a graduate student at Ohio State when I was there, and is now an assistant professor at St. Mary's College of Maryland: "Give me an instance of language that isn't a representation. Even articles are metaphorical—although they don't stand in for a real-world thing or action, they do stand in for an idea or concept; a, an, the, and conjunctions—and, but, for—have no meaning in and of themselves")

These letters—T, R, E, E—aren't a tree, though they make me think of one. And my thinking of a tree (I can see one clearly in my head, right now) isn't a tree, either (Buddhists would say that even the tree isn't a tree, that it is an illusion). I've a conception in my mind that I compare to the great plants outside my window and both of which I compare to those four letters above and to a sound I can make with my lips. The sound isn't the plant or the letters or the conception, but yet another point along the tree continuum. When I use the word to invoke a particular oak tree in, say, in a scene that includes the tree, a scene that is about my father's strength, as well, the word means both the tree itself, but also refers to my father, and to his strength, but not in a precise way: some readers may think of the rigidity of oak wood, its tendency to break in high wind, others may think of the way dead oak leaves hang on through whole winters before letting go, giving way to the new. This oak tree is a fully literary symbol.

If, while writing, I point to the comparison, saying, "My dad is like that oak tree," I'm making our symbol into a simile, not quite trusting the reader to make the leap himself. And while readers should always get your trust, writers, they do seem to need help here and there, and if the comparison is important to your purposes, it's often best to make it overt. Subtlety isn't overrated, but it can leave certain readers behind. How many do you want to keep? Not all readers are metaphorical thinkers, not at all.

And literal thinkers can drive you crazy.

If I say, "That oak tree is my dad," a literalist could put me on the stand, point a finger, and accurately accuse me of lying.

But your honor! I didn't mean it literally! I'm making a simple metaphor, the boldest kind of comparison. And metaphor is a figurative kind of honesty. And it's what we mean when we talk about emotional honesty, isn't it? That by making associations, comparison, contrasts, I am explaining how I feel about a person, place, or thing.

I'm not lying after all.

How complicated is the truth!

My father is a tree.

The sky is steel.

[Adapted from Writing Life Stories (Tenth Anniversary Edition): Story Press, 2008]

Losers

Americans aren't too keen on losers and losing. I thought about this during the pain of the Patriots' loss over the last couple of days. "Pain" is the right word, even if it seems overdone to non-sports fans. I know there is a big gap between people–and between the readers of these pages–on how seriously they take these things. It was nice of my wife Nina to pat me on the back and console me after the game. But you had the feeling this was a little hard for her to take seriously, as if I were consoling her after someone she liked got kicked off The Bachelor.

Americans aren't too keen on losers and losing. I thought about this during the pain of the Patriots' loss over the last couple of days. "Pain" is the right word, even if it seems overdone to non-sports fans. I know there is a big gap between people–and between the readers of these pages–on how seriously they take these things. It was nice of my wife Nina to pat me on the back and console me after the game. But you had the feeling this was a little hard for her to take seriously, as if I were consoling her after someone she liked got kicked off The Bachelor.

I don't care. It did hurt. If only through empathy—for instance seeing Wes Welker–great, gutsy Wes Welker–cast as a goat, his eyes red from crying and his voice quiet. And not only empathy. I was sad for me as well as them. When I think Patriots I think sitting on the aluminum benches at Schaefer Stadium with my Dad watching Sam "Bam" Cunningham or Randy Vataha, so yes I sometimes say "us" or "we" when I refer to the team, feeling at least a much a part of the whole thing as last year's third round draft choice. Still, I didn't expect to suffer this time. Hadn't dread fled New England after the Sox won and the Pats did a judo flip on their perennial loser tag? In the days running up to the game I talked to a couple of friends who had grown seriously depressed after the loss to the Giants in 07/08. I felt for them, but I thought "I'm different…I get all the pleasure of rooting for the team but I no longer let what happens on a football field affect my emotional life. It's only a game after all."

I was dead wrong. The loss crushed me. I think one of the things that is lost when you lose is possibility and as the Pats drove down the field in the second half—so efficiently it looked like they should do it very time—my mind already rushed ahead to possible glory, though tinged with fear of course. Then when the fumbles starting to bounce the wrong way the old New England dread returned….

Of course it is different for me than it is for Wes Welker. It's Tuesday morning as I type this and the intense pain has faded (the dull pain will stay until we win again.) For Welker career and reputation have been altered, and he is enduring what his quarterback called the "a week of sleepless nights." Hopefully, he isn't watching a lot of television where the blowhards of Sports Center are busy elevating some reputations and destroying others. I am reminded of the publishing industry where, after a book has done well or poorly in the market, the less-sane agents and editors scramble to paste a narrative, a reason, atop the randomness of things. A football game hinges on the random, too, but that won't do if you have hours of air time to fill. There was a telling moment at the end of the first half when the Patriots scored and the announcers, who had just seconds before been confidently relating the narrative of why the Giants were playing better, scrambled to reverse themselves and explain why the Patriots were the better team that day.

On a small scale, I know a little of Welker's pain. During my years playing Ultimate Frisbee, I never won it all. We would train for eight months and the effort to win the national championship always shaped the year. I have many friends who did win nationals, but I did not, so it could be argued that the whole thing was a waste of time for me. I think differently, but there was certainly a lot of pain involved. One year in the semifinals of Nationals down in Florida, the season ended with a bad throw from my own hand. Believe me that was a little harder for me to get over than Sunday's loss.

In today's sports culture we are quick to say someone is "clutch" or that they "choke." What is forgotten is that most human beings, even well-trained athletic human beings, are some combination of both, different people in different moments. Maybe Michael Jordan screwed things up for everyone else by being so consistently cold-blooded, but I certainly remember both Magic and Bird having their share of choke-y moments. There has been a lot of anger directed at Tom Brady over the last couple of days for "letting us down." Please. If the ball bounces a foot higher after the last second endzone heave, and Gronkowski comes down with it, Brady is Doug Flutie re-born, his reputation not just in tact but shined to shimmering, and the 16 complete passes completed in a row are the stuff of legend. The problem with elevating winners to heaven and consigning losers to hell is a simple one: it is a lie.

"For us there is only the trying," said T.S. Eliot. This is the deep truth that the sports blowhards, and most of us, don't really get. The effort, the shape, the attempt. Take writers for instance. We throw our entire selves into making books. Our "season" often lasts several years and, almost invariably, the result of our training and effort, is some sort of worldly failure: either the book is not published or it falls short of our expectations for it. Does this mean our efforts were pointless? The sportscasters in our heads would have it so, writing their narrative of failure. It is up to us to wrestle back the narrative, to turn it into a story of effort, bravery, and persistence.

But enough pep talks. It's okay to be sad. That's part of it too.

February 6, 2012

The Ghosts of Rocky Flats

Twenty-one years ago this month, when I was twenty-nine, I learned that I had testicular cancer. As it happened I had recently returned to live in Worcester, Massachusetts, my hometown, and I joked to friends that I didn't know what was worse, cancer or Worcester.

It was in Worcester that I underwent an operation to remove the malignancy and then endured a month of radiation treatment. And it was in the middle of that treatment that I, feeling queasy the way I always did during that ugly month, got a letter in the mail that would prove to be a kind of deus ex machina in the story of my life. The letter informed me that I had gotten into grad school in Boulder, Colorado, and less than four months later I left Worcester behind and moved to the appropriately named town of Eldorado Springs, a few miles outside of Boulder.

It was a deliverance of sorts. I would end up writing a book about the re-birth I experienced by moving west, but the short version is that I fell immediately in love with my surroundings. Gradually recovering, I threw myself into first hiking and then running the trails up into the flatirons, swimming in the creek, watching the swifts and falcons carve the sky as they flew down from the canyons, and biking up the roads above the city. Of course this sort of activity is not unusual in Boulder, since being unfit is against the law there, but I approached my own regimen of fitness with the particular vehemence of the recovered. Or, I should say, recovering. Because of course, somewhere in my mind, I feared cancer's reoccurrence.

"If I'm going to die," I wrote in my journal. "It will be in the best shape possible."

There was an irony to my, and the town's, focus on health. To the south of the city, not far beyond where I lived in Eldorado, stood Rocky Flats, a plant that made plutonium triggers for nuclear bombs. Rocky Flats had only about a year left as an active plant when I moved there, but it already had a history of disasters. Dow Chemical broke ground at the plant in 1951, and by 1957 twenty-seven buildings had spread over the grounds of the facility. That year a fire broke out that released plutonium into the atmosphere, and two years later radioactive barrels were found to be leaking, a fact that was not released to the public until eleven years later, in 1970, when "wind-borne particles were detected in Denver."

More fires and leaks followed, resulting in the "costliest industrial clean up in United States history to that time." Some 4,600 acres of land were purchased as a buffer zone around the plant, but water did not respect these borders, and nearby creeks were found to have elevated tritium levels. Meanwhile, topsoil at the plant was discovered to be contaminated with plutonium. The plant closed in 1992, but the plutonium, with a half life of 80 million years, lingers like an industrial ghost, haunting the scarred grounds.

In his brilliant essay, "Technically Sweet," Reg Saner, a Boulder resident, writes of just how deadly plutonium can be to human beings: "Plutonium doesn't have to be in a bomb to kill me. Its toxicity in the human system is almost beyond belief. One half of one hundredth of one millionth of a gram isn't exactly oodles. However, a half-hundredth microgram dose of plutonium 239 per gram of bloodless lung has been shown to produce cancers in 100% of dogs used for experiment. And through Rocky Flats pass tons of the stuff. Since latent cancer may take 20 years or more to announce itself, plutonium is the perfect industrial murder. Two decades from now, if my lung cells betray some long-hidden, accelerating derangement, there'll be no clue to that cancer's having begun this afternoon, with a given breath."

Like me, and like so many Boulderites, Saner was an active biker, and he sometimes pedaled right by the plant. He was well aware of the potentially unhealthy consequences of this healthy activity. This paradox was eventually confirmed by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, which, in its report on Rocky Flats, concluded: "People who lived near the plant and led active, outdoor lifestyles had the highest level of exposure to airborne plutonium."

* * *

This week, as I celebrate cancer's anniversary, I have been thinking about health, both public and personal, and about the need for conscientious oversight and, yes, for clear-sighted regulation in our lives. One of the things I find most troubling in our current national debate is the idea that freedom and regulation are antipodes. "Regulation" may make a nice bugaboo, but can anyone seriously believe that it is a good idea to do away with most of it? Or to put it another way, without it where are we? Any reasonable adult knows that regulation and freedom go hand in hand, that the two rely on each other for balance. What is the personal equivalent of regulation, after all, if not self-discipline? And how can a life be free without restraint?

I can say honestly that I never felt more free than I did during those first weeks in Eldorado Springs, roaming the hills, dipping into the creeks, feeling health surge back into my limbs. I had left dirty Worcester and radiation behind, not yet aware of the potential radioactivity of the neighborhood I was celebrating. To a certain extent, Rocky Flats and I have had parallel journeys in the years since. Five years out from my cancer I was declared "clean," and ten years later so was the by-then-Superfund site of Rocky Flats. In 2005, the clean-up of the site was declared officially complete, and in 2007, four thousand acres of what had been the plant's buffer zone became the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge.

At fifty I feel strong, but like any cancer survivor, I am on not-unfamiliar terms with occasional dread. Meanwhile, mule deer and elk roam the former industrial site, through a habitat containing hundreds of acres of rare xeric tallgrass prairie, and meadowlarks sing from the ground while northern harriers and peregrine falcons fly above. I'm sure there are days when one could look out at the place and it would seem a kind of paradise.

February 4, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: Winter Color

On my winter way there's white, there's black, and there's every shade of gray between. But here and there a splash of color, or a subtle nod.

A bit of blue.

High-bush cranberries, beloved of Robins and Bohemian Waxwings

Yellowed orchard grass.

Death of a vole, with fir cone.

Fox tracks. Watch it voles!

Red osier willow (redder and redder as spring approaches)

Moose browse and Sapsucker taps.

Back to nature, blue.

A partridge landed and walked.

Sub-flock of Bohemian Waxwings.

Beech leaves yellow, balsam green.

Blue.

Golden-retriever-gold red-oak leaves.

Your moss is showing.

Ski dog.

Sumac flowers.

Ever wonder where those blue tarps end up?

February 3, 2012

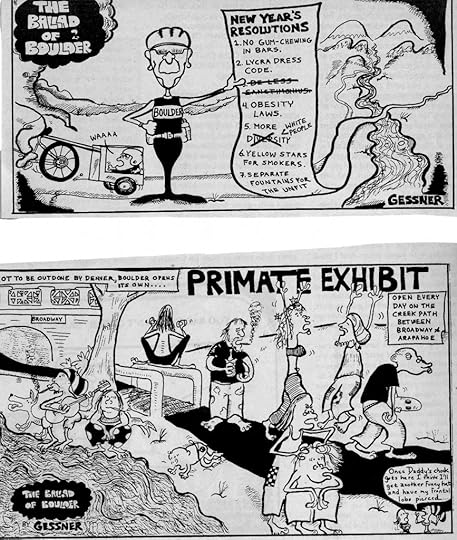

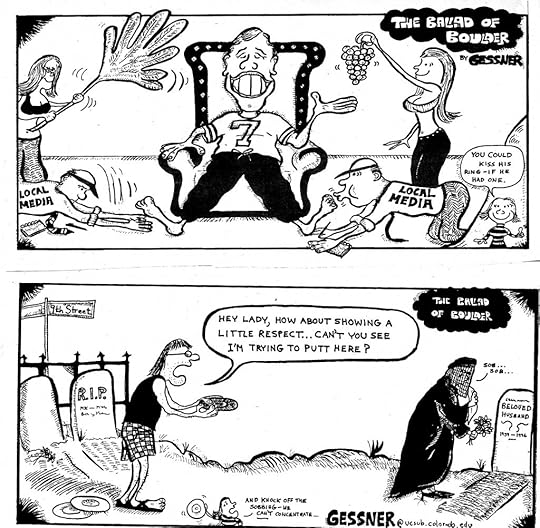

A Few More Ballads

While I was digging out the Rocky Flats cartoon I came upon a few more Ballads of Boulder….

Obviously the one below is from before John actually had a ring to kiss…

February 1, 2012

Bad Advice Wednesday, Superbowl Edition: VINCE WILFORK, C'EST MOI

Monica Wood is today's special guest star. She is the author of Any Bitter Thing, Ernie's Ark, My Only Story, Secret Language, the Pocket Muse series for writers, and the forthcoming When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine.

Monica Wood is today's special guest star. She is the author of Any Bitter Thing, Ernie's Ark, My Only Story, Secret Language, the Pocket Muse series for writers, and the forthcoming When We Were the Kennedys: A Memoir from Mexico, Maine.

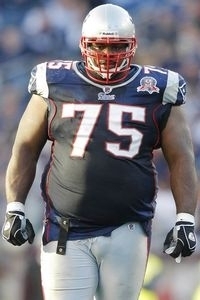

VINCE WILFORK, C'EST MOI

Football, like all sport, teems with metaphor, boasting a long, tedious tradition of Teaching Young Men About Life. Agony, ecstasy, teamwork, character-building, yadda-yippity-yadda. But for those of us who are a) already built, characterwise; b) old enough to have absorbed our allotted portion of agony, thank you; or c) female, football is all about the glam and glitter of the offense.

Behold the snap, the hike, the bullet pass flying straight to the steely midsection of a wide receiver! Behold the gorgeous spirals! The gazelle-like runs! The circus catches in the end zone! No wonder these guys get all the glory, all the press, all the endorsements, all the girls. The quarterback and his posse: bestsellers of the Astroturf. For them the crowd chortles, it caws, it spills its beer, it waves many misspelled signs. What's not to love?

Well, nothing, come to think of it. It's just that, as a midlist American author, I love the defense more. Especially the lowly, laboring, monster-size defensive tackles. Overfed and underpraised, they lumber out to the line of scrimmage all game long, snap after grueling snap. Their numbers tend to run together. They do not show well in spandex. But they know their job, and they do their job, which is to thwart the opposition by annihilating whatever unlucky human form stands in the way. They perform a single job that's more complicated and painful than it looks. Just like us. And like us, they dream of one day finding the ball in their hands (hey, it happens) and running like a water buffalo all the way to the end zone before one of the gazelles catches on.

Although my team, the New England Patriots, possesses arguably (I said arguably!) the best quarterback in the history of the NFL, is it Tom Brady to whom I raise my humble eyes when searching for a consoling literary metaphor? No. The J-Franz of football, sleek and strong and cute as the dickens, is not my guy. It is the defense to whom I turn, the defense from whom I discern the putative life lessons to be found in sport.

Although my team, the New England Patriots, possesses arguably (I said arguably!) the best quarterback in the history of the NFL, is it Tom Brady to whom I raise my humble eyes when searching for a consoling literary metaphor? No. The J-Franz of football, sleek and strong and cute as the dickens, is not my guy. It is the defense to whom I turn, the defense from whom I discern the putative life lessons to be found in sport.

It's a little late for me to become a quarterback of American letters. Let's just say I "blew out my knee" years ago. (Oh, wait. That part's not metaphor.) When in need of solace and inspiration—as I am now: floundering, out of ideas—I look to a certain sweet-faced, supersized DT for all the lessons I require.

Vince Wilfork. Vince the invincible. The round mound of get-down.

My Vince, who groans into position, reads the offense, and then roars up, like a pissed-off hippopotamus, to clog the gap and otherwise harass the pretty boys on the other side, often steamrolling 700 pounds' worth of offense at one go. He eats his Wheaties and also quite a bit of sod. He moves with the grace of a kitchen appliance strapped to a dolly. His job is repetitive, punishing, inglorious, low to the ground. How he manages to breathe in there I cannot comprehend.

But here's the thing. He loves it. Which is why I love him. The maestro of mayhem plays not for the glory (a shirt with his number cannot be found in my local sports shack); he plays for the guts, for the grind, for the love of the game.

But here's the thing. He loves it. Which is why I love him. The maestro of mayhem plays not for the glory (a shirt with his number cannot be found in my local sports shack); he plays for the guts, for the grind, for the love of the game.

And so I say unto you, fellow tacklers of words: Channel your inner Vince! Published or not, shiny-faced beginner or sour old vet, you have within you a 350-pound nose tackle ready to push off, helmet first, into the fray. Now get your lazy ass out on that "field" and write! You can! You must! Because, in the words of the unvenerated number 75, "Every game, it just git harder."

January 31, 2012

Game Ball! (Superbowl Teaser before tomorrow's Bad Advice, Superbowl Edition)

Since moving down to North Carolina eight and a half years ago, we have not gotten back to Cape Cod nearly as much as I'd like. But when we go, we go in style. We have lucked into a great house-sitting gig in town of Brewster near Slough Pond. We stay in the home of Katy Sidwell, an artist, extravagant and generous, and Steve Sidwell a former defensive coordinator for the Patriots, Seahawks, and Saints. While the Sidwells are away, we walk their dog Buddy, watch their art-filled house, feed their cat/s, mow their lawn (in summer), soak in their hot tub. (When Hadley was young we sang a song that another friend and I made up about this last activity to the tune of Foreigner's "Hot Lovin'", "Hot tubbin' check it and see/ got a temp of 103!")

Since moving down to North Carolina eight and a half years ago, we have not gotten back to Cape Cod nearly as much as I'd like. But when we go, we go in style. We have lucked into a great house-sitting gig in town of Brewster near Slough Pond. We stay in the home of Katy Sidwell, an artist, extravagant and generous, and Steve Sidwell a former defensive coordinator for the Patriots, Seahawks, and Saints. While the Sidwells are away, we walk their dog Buddy, watch their art-filled house, feed their cat/s, mow their lawn (in summer), soak in their hot tub. (When Hadley was young we sang a song that another friend and I made up about this last activity to the tune of Foreigner's "Hot Lovin'", "Hot tubbin' check it and see/ got a temp of 103!")

One other perk of staying at the Sidwells is that I get to write downstairs, in Steve's office in the basement, a space that more than earns the phrase that I first heard six years ago in relation to it, the now over-used "man cave." But this Man Cave is more manly than most. Who else gets to have two large desks, not to mention pictures of oneself as both middle linebacker at the University of Colorado and with the Saints linebackers? Steve looks and acts the part of the football coach: he has great charm, the capacity to eat large amounts of food, and the growling resonant voice of a talking bear. And, since I admire him so much, I have taken great pains to respect his work space, just as I hope some future house-sitter will respect mine. The one exception to this rule has been in my relationship to my favorite piece of memorabilia in Steve's office, the game ball from the Patriots win over the Dolphins on the last game of the regular season in 1997.

I remember that game, to decide the division title if memory serves, as a bloody battle, a brutal defensive struggle, so it's not surprising that the D. Coordinator ended up with the game ball. But I have since had my own brutal struggles involving that ball, though they usually just involve words, not clashing lineman, as I pace back and forth, working out sentences while tossing the game ball up and down for inspiration. Only once have I broken the ball out of its home in the basement and that was for this season's last regular season game, which found us at the Cape in the Sidwell's house. I credit Tom Brady and the rest for playing well that day, but I'm pretty sure it was the way I clutched tight to the game ball that secured the victory. And when victory was secured, along with the first seed in the playoffs, I returned the GB safely to its shelf in the man cave.

I am not a superstitious, but it can't hurt to cling to a relic of past glory, can it? I'll be rooting hard on Sunday but, lacking my talisman, I am not entirely confident of the outcome. Hopefully somewhere, a thousand miles to the north, someone will have taken the lucky game ball from its sacred perch and will be holding it tight.

January 29, 2012

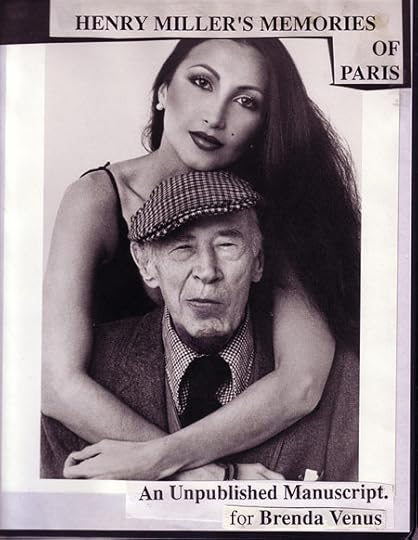

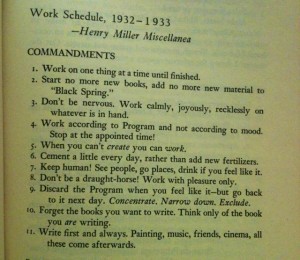

Henry Miller's Commandments

A photo of a page from a yellowed book has been going around Facebook: it's Henry Miller's commandments, just a note he jotted to himself while living and working in Paris, c. 1922. It's collected in a New Directions paperback called Henry Miller on Writing. And he was a guy who had a lot to say on the subject.

I revered him in my twenties, living with friends in a loft in SoHo, reading, reading, reading, writing a little, too. He wrote a lot about sex. Opus Pistorum, which he wrote on commission for some rich pervert, is almost disgusting. What an imagination. Or at least we hope it's from his imagination!

Miller's studio at Villa Seurat

He would paint pictures for his keep in Paris. If you gave him lunch, he made you a painting. Imagine what those paintings–if any are extant–would be worth today. He even kept a schedule of meals, breakfasts, lunches, dinners, all at friends and acquaintances houses, a whole month's worth, to be repeated.

I learned that in The Books in My Life. Also that he didn't keep books, but made a point of giving them away. So I gave my books away for a few years there. I miss some of them a lot. Including The Books in My Life.

In any case, if you haven't seen them lately:

Commandments

1. Work on one thing at a time until finished.

2. Start no more new books, add no more new material to "Black Spring."

3. Don't be nervous. Work calmly, joyously, recklessly on whatever is in hand.

4 Work according to the program and not according to mood. Stop at the appointed time!

5. When you can't "create" you can "work".

6. Cement a little every day, rather than add new fertilizers.

7. Keep human! See people; go places, drink if you feel like it.

8. Don't be a drought-horse! Work with pleasure only.

9. Discard the Program when you feel like it–but go back to it the next day. Concentrate. Narrow down. Exclude.

10.Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you "are" writing.

11 Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.

going around Facebook

Mornings:

If groggy, type notes and allocate, as stimulus

If in fine fettle, write.

Afternoons:

Work on section in hand, following plan of section scrupulously. No

intrusions, no diversions. Write to finish one section at a time, for

good and all.

Evenings:

See friends. Read in cafes.

Explore unfamiliar sections–on foot if wet, on bicycle if dry.

Write, if in mood, but only on Minor program

Paint if empty or tired.

Makes Notes. Make Charts, Plans. Make corrections of MS.

Note: Allow sufficient time during daylight to make an occasional visit to museums or an occasional sketch or an occasional bike ride. Sketch in cafes and trains and streets. Cut the movies! Library references once a week.

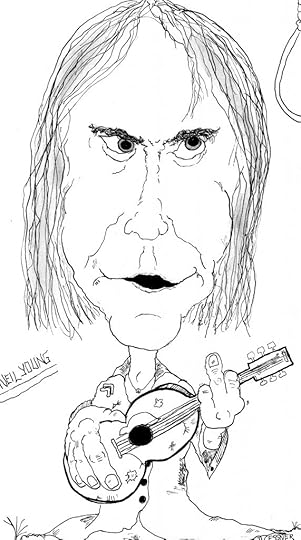

Don't Let it Bring You Down

Digging through the old 'toon files, I found this, circa 1978, which puts me in high school at about 17. Back when I worshiped all things Neil……(Come to think about it still do.)