David Gessner's Blog, page 93

February 20, 2012

Rare Mystery Bird Identified

Bohemian Waxwings: Easy I.D., But a Rarer Bird Awaits

.

This morning on my daily rounds a flock of about two dozen Bohemian Waxwings followed me for more than a mile, flying in various factions from tree to tree, for a while stopping to sip at a break in the ice, Temple Stream. The sky was very, very blue. The birds are almost blue, but gray, with beautiful yellow tail tips and yellow in their wings (the sealing wax of their name, I guess). Baila the dog took a drink in the freshly exposed current, and by all signs you'd guess the date was March 20, not February 20. We walked on the ice, like breaking glass, all these layers and shelves and store windows, noisy. In the alders ahead I spotted a bird. I looked the other way so as to misdirect Baila, who obliged, tearing around the corner smashing chalices. And put the binooculars to my eyes. Small movements. A lot of black . Some yellow. Large, a little bigger than a Robin. I flipped through the indexes in my head–nothing. If I'd been in Montana, in summer, maybe a yellow-headed blackbird, but no, no. Casually I crept closer. And closer yet. The bird paid no mind, but kept up its subtle swinging movements. Closer. Still impossible to identify. Closer, Baila returning with a great crashing. Brave bird didn't move. Closer. And if you click READ THE REST, you'll see what it was. Amazing, rare, and clearly a wayward denizen of the upstream backyards.

.

Waxwing Watering Hole

A Letter to a Neighbor

[image error] You will be moving into your new home soon and, as ours is a small community, the neighborly thing for me to do would be to bring by a tin of cookies or fudge. Instead I send this letter. Cowardly by nature, I'll probably slip it under your door. It's not the sort of thing likely to elicit the smile brought on by a note from an old friend, or even the irritated glance aimed at junk mail, and you'll surely toss it aside at some point. If I had the courage to stick around while you read my words, you'd no doubt turn to me and counter my own flimsy, idealistic arguments with more solid and practical ones. "What right do you have to tell me what to do with my land?" you'd ask. "I bought it with my own hard-earned money. Furthermore, if I hadn't built my house here, the place would be checkered with subdivisions."

You'd be right of course. And I should be grateful the land wasn't further developed. But I'm an ingrate, and ingrates, by nature, complain.

"It's a goddamn desecration of place," another of your new neighbors said recently. That's the word–desecration–that keeps coming up when I think of what you've done to your land. I don't use the word lightly; in fact, I use it just as it was meant to be used.

I have walked the path to the bluff, your bluff, since I was a small child, first holding my mother's hand, then exploring on my own. From a young age I understood that this land was different from the rest of Sesuit Neck. The sound of building is never far off onCape Cod, but neither is the sound of the ocean, and the ocean insists on wildness. Your property, due to a coincidence of wealth and geography, remained the wild heart of Sesuit. Stone's bluff heaved out from the shore like a great whale-backed beast, a jutting heath transported directly from a 19th century romantic novel. Approaching it by beach from the harbor, you travel from tame to wild, first walking past the overdeveloped private beachfronts, then past the public beach and Bagley's, and finally leaving all houses behind. As an adolescent I had a distinct sensation of relief when, moving past the last of the homes, no longer feeling windows or eyes staring down at me, I began to walk faster, excited, out to greet the bluff alone.

Part of what assured this solitude was the rocky terrain. Except at dead low tide, the land below the bluff could only be walked by jumping from rock to rock, and most beachgoers, fearing bloody shins, didn't take the risk. But the brave were rewarded. Once past the sandy stretch, and headed toward the point, anything could happen. Seals basked on Tautog rock, floats of eiders bobbed off-shore, and, if you got there before dawn, you might see deer licking salt off the rocks. It was as if by walking less than a mile from the harbor, you'd passed through a door into another world.

Not a quiet world. Weather reached Stone's bluff first, and, often, summer turned to fall when you arrived at the jutting spit. The sky above would pile up with clouds, enormous cloud continents with dark violet interiors and flashes of gold escaping from the coasts. Long shadows shafted down the sand, my own goofy dark doppelganger stretching out in front of me as I walked. Sometimes the open beach barely let me approach–warning me off with sand stinging my face. Gulls drifted by sideways. Trees and grasses bent and ran from water and wind. Light dry sand flew spectral over the darker sandbar sand like a curtain revealing the blue-grey ocean and purpled clouds. Even on the rare days when the waves rested, the rocks seethed with life. Barnacles hissed and crabs scuttled and swallows darted and swooped down from their cave homes in the brown cliff wall.

As with any good relationship, mine with the bluff deepened over time. After college I came to Cape Cod to write, and that fall, standing on the point like the bow of a ship, I watched as the wind swept out summer's clinging heat and ushered in the clarifyingCapelight. It was below the bluff that I learned that nature can provoke two profound and opposite reactions: stunning you into a near doltish silence when faced with the ineffable, and causing you to run for your pen. The latter reaction was more common; lists gushed over the pages of my journal and punctuation fell away like something withered and dead. I recorded random sights and sensations: a red-tailed hawk treading air in the stiff wind…the smell of cut grass and grapes…the bloody mucous inside of a periwinkle….the smell of celebratory cigars wafting to the beach the day the cranberries were harvested…

Then, just as it was as good as it could get, it got better. The real weather blew in and the leafy world reddened, poison ivy and sumac bloodying the edges of the cranberry bog. Not wanting to squander any opportunity for joy, I often reached the beach before dawn to watch the show. When the birds called up morning that was my sign to wake and head to the bluff. Later, at sunset, I'd return to catch the dying rays of light, sipping a beer and watching a pumpkin orange moon rise.

This overindulgence, this binge of color, led to a long hangover, and I had to leaveCape Codfor a while. But over the years I've kept coming back. Gradually I've learned that for the bluff each time of year is both itself and a moving toward–the spare clutching of the pitch pines in mid-winter becoming the island bloom of late spring. For a while, in my twenties, I tried to write a novel, a kind of grandioseWutheringHeights, which I set on the bluff. Years later, older and calmer, I wrote a book of essays aboutCape Cod, and it wouldn't be much of an exaggeration to say that the bluff was the book's main character. The book ended with the spreading of my father's ashes out on the bay beyond Stone's point, after which I walked out alone toward the bluff at sunset, seeking refuge.

Perhaps by now you've put this letter aside. But if I've gone overboard with my descriptions it's only to try and impress upon you how much your land means to me. To convince you that, to the degree that places can be sacred to human beings, I hold this place sacred. Assuming that I have at least partly convinced you of this, I can begin to address what you have chosen to do to my sacred place.

In these times, half of truly loving a place is a healthy hate. Hate is a strong word, of course, and one that is often fenced out of the reasonable pastures of the nature essay. But hate is what I feel and hate, as well as love, is what compels me to write today. I apologize in advance if some of the things I'm about to say sound rude and unneighborly. But I would contend that you have acted quite discourteously yourself, that you came to Sesuit Neck, not like a neighbor or friend, but like a conqueror from another land, first unleashing a fleet of trucks like tanks rumbling through our streets, then securing a beachhead, and finally razing our beloved capitol. This is not generally considered polite behavior.

Furthermore, you seem not to have bothered to take the time (and it can take some time) to learn about the place you've moved to, but rather, acting with an intruder's mentality, have imposed your ideas from the outside. You'll be happy to know that there are many in the neighborhood who insist you are a "good guy," and I'm sure that in person you can be charming. I can be fairly charming myself, and perhaps if we'd met under different circumstances, we might have drunk a beer or two and become friends. But while I've no doubt that you're a "good guy," I also have no doubt that it's good guys like you, with your blissfully thoughtless adhesion to old-time progress and just plain BIGness, who are destroying sacred places like this one all over the world.

But before I work myself into full froth, let me climb down from my soap box and get specific. Your house. Since humans first settled here they built their homes low and strong, a logical and organic reaction to the daily assault of wind and water. This is how things grow onCape Cod, and how they have long been built, a response that evolved directly from place, and an intimate knowledge of that place. For inspiration you need have looked no farther than the pitch pines and scrub oaks that crawl mangily across the humpback of your new back yard, a yard you'll find to be one of the windiest places on earth. If you had been in a listening mood, the trees would have spoken directly to you, whispering "stay low," and, heeding that advice, you could have still built a large and beautiful structure. But, you may have reasoned, with modern building materials and techniques making the old restraints irrelevant, why not spread as far and high as I can go? Why merely become part of the bluff when you could rise above it? Why indeed. Well, stifling the moralist's urge to tell you to go back and read the story of Icarus, I'll suggest there were simpler reasons.

You might have paused and considered your neighbors. Not just the deer whose paths have forever weaved through the brambles you tore down or the swallows who for countless generations have made their homes in the undercusp of the bluff where tractors now rumble, but the three hundred or so homo sapiens who dwell here in different seasons. You might have, dare I mention it in this day and age, minded your manners, and said, well, since I'm tearing down this mansion, this neighborhood landmark, I'll consider the others who live here and, while of course building a large place, will try to fit gracefully into my new home. This was not the option you chose. The house you chose to build would dwarf a shopping mall. Proof of that is the way it seems to dwarf what had previously been the Neck's most prominent feature, the bluff itself. For the first time since I was born the silhouette from the beach is not of humped land descending like the back of a sleeping giant, but of a castle sprouting into the air, proclaiming dominion over its once wild surroundings.

Instead of wisely sitting back from the ocean, your building peers over at those of us who still try to walk this spit. In a way I admire your nerve, daring the ocean. But of course you believe you can control large forces. This winter I felt the ground shake as earth-moving machines dumped more of the $300,000 worth of fill. Most of the old mansion, which looked like a dollhouse beside your plywood palace, has been torn down, and most of the fields and brambles ripped up. Meanwhile your grandson patrols the grounds in a golf cart, scaring off deer and neighbors, yelling at one long time resident to "stay off my property." Below the bluff the sounds of the ocean are now punctuated by the backward beeping, the mating call of trucks that invades every moment of our waking lives. Most of us were sure the frame was complete a few weeks ago, since your house already rose several stories above any structure we'd ever seen in these parts, besides Scargo and the water towers. But then you added a final room on top of it all, an observatory or walled-in widow's walk, as if to say, "Why not go just a little bit higher?"

Despite my state of high dudgeon, I, walking below on the beach, have looked up and fantasized about being the carpenter sinking those final nails, staring out at the neck from that wooden aerie. I'm not above the urge for a dream house myself, and I'd have been happy for you if you'd built a grand house, even an enormous house. That this would have been fairly easy should be evinced by the simple fact of the previous home. The bluff is of such magnificent scale that a mansion–a mansion!–was able to fit snugly into place. But the sad and frustrating thing, the thing that causes me daily depressions and stabbing pains–and this is especially sad if your are indeed a "good guy"–is that a dream house or mansion wasn't good enough for you. You could not tolerate merely becoming part of this beautiful, beautiful bluff, but had to dominate it. Yes, dominate. Sometimes the sexual metaphor is unavoidable. You haven't exactly sidled up and wooed this land have you?

As I write I try to hold myself back, to temper my impulse to use words like "rape." After all it's only a piece of land. This sort of thing is going on every day, and we'd better inure ourselves to it. "Sesuit Neck was ruined already," said a neighbor, and maybe so. But in this neighborhood two things have mercifully slowed the rush. One is the marsh, which winds through Sesuit Neck like a mucky subconscious, and the other is the land below your new home. Ticks and stink make walking the marsh on a daily basis impractical, so most often I go to Stone's to have my few moments in a world without people. But not completely without people, and that is the paradox of that bit of land, it's a place for the community as well as the solitaire. Below the bluff I may run into J.C., who collects shells for his driveway and gathers wood for his fire, or dog walkers who want a minute free to think. That is what this point has really meant to the neighborhood: a place where you could go to get away, a place where seals and wild birds exist.

"Our neighborhood Holiday Inn," an old friend of my father's calls your new home. People grumble, now that the true scale of your attack is being revealed, but I've noticed that few express outrage. They are used to it, you see, the gradual decline and destruction brought on by "improvements." Used to having every brambled corner of the neck torn up, every copse of locust chopped down. They accept it as "progress," the way of things, which I, of course, should also do.

But can't.

Again I apologize. My parents raised me to be courteous, and fanaticism doesn't come naturally.

It's been a long road to get to where I am today. Please understand that if I sound angry it's only because I'm being stripped of 36 years of connection and memory. I understand that, according to the law, your deeds and title say more than my little essays about who has the right to this land. It's yours unequivocally to do with as you will, and, again according to law, my love for this land means nothing.

The truth is, if I keep calm, I really do think I understand what you've tried to do. You're obviously an ambitious man and in that we are alike. While your workers hammer away up on the hill, I hammer away at my keyboard. Like you, I dream of creating something big, something great, and, like you, I sometimes feel as if my passion for this controls me, not me it. But we are in control more than we admit, more than it's fashionable to say these days. I don't suggest the laughable premise that humans are rational creatures, or that reason controls our lives. What I do suggest is that our imaginations can be nudged, and work best if nudged earthward. For me it's been a question of learning that, when my words rise too high they become brittle; that they are better when connected to earth. That is, I want my books to be like a goodCape Codhouse that seems to grow out of the surrounding ground. It's not that I've given up ambition. Hardly. It's just that my ambition now is to stay closer to the earth.

Perhaps you thought you could simply plow into and over our Neck without any cries of protest from us humble villagers. Well, this is my cry and it won't be my last. I'm a relatively young man with a long writing life ahead of me and, as long as I have strength to type, I plan on making your home into the symbol of everything I despise. I admit to taking some vindictive pleasure in this. But that is my worst motive. I have better ones. I write today with a purpose. I'm tired of creating lyrical nature essays. This piece really is for an audience of one–that is, for you. And, keeping that in mind, I'd like to swallow my anger and change my tone. Impotent rage gets old fast. I'm ready to stop ranting and turn this letter into what it really is.

What it really is is a plea. An appeal to your better instincts–to the "good guy" in you my neighbors speak of–to the amateur not the professional, to the man whose wild impulse made him want to live on this wind-swept bluff, not the man who built to dominate it. An appeal to the quieter, deeper voices inside you, to your own marshy subconscious.

My plea is this. Leave the beach wild, and leave as much of the bluff wild as you can. This morning I saw the orange florescent paint on the rocks you plan to plow away, and the fleet of tractors close to the bluff's edge, close enough to possibly scare off the swallows. Smoke wound out of the briars as if the bluff were a chimney; the sand on the beach vibrated. It looked and felt to me, as it must to the birds, like the end of the world. Hyperbolic perhaps, but true. Everything I know about the world, everything I love and hate, comes down to this single place.

Please have the tractors back up. Let the rim by the cliff's edge remain the territory of the deer and birds and of the coyote I saw hunting there the other day. Let the beach remain a place where people need to risk bloody shins to walk. Don't turn what has been home, classroom, gymnasium, observatory, study, and wild place into mere beach.

Leave it inaccessible. Resist the urge to domesticate, to tame. Give this one gift to your neighborhood–a last patch of wildness–and I guarantee you will be surprised how much your neighborhood gives back to you.

By now you are truly sick of me and my thundering.

Who can blame you?

But let me try to end on a courteous note. Maybe we will never share that beer, but, perhaps, in the end, we can be considerate neighbors. While this isn't exactly a tin of fudge, it isn't a letter bomb either. My fantasy is that you will reconsider, pause, and keep the bluff as wild as you can. Perhaps if you do this, your house, despite its grand ambitions, will begin to take root in the land, connecting to the earth so it can weather the blasts of wind that will blow up from the sea.

Finally, bear in mind that if my words sound occasionally venomous, it's because this is a difficult time for me. It used to be that I was pulled out to the bluff, that I almost couldn't help walking there, my feet leading me excitedly to that place beyond human eyes where the seals were. Now I have to decide, on a day-to-day basis, whether I'm up for the depression, anger, and fear that will surely well up if I head in that direction. For me it's a time of loss. So please remember that, if there is hate in this letter, it was born of the opposite emotion. To put it as bluntly as possible, I love your land. In time I hope you will too.

February 18, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: It's All About Ice

Rain, freeze, drain, sag, leaf.

We've had little snow, a certain amount of melting, cold nights. The stream is an ice-way, strange beauty abounding.

Ice-skating dog

Hoarfrost on orchard grass

Ice abstraction

The stream breaks out: early spring?

Mink entrance

Human den

Crack.

Pretty icicles, or sickening ice jam?

February 17, 2012

Dave's Jungle Adventure! (Really!)

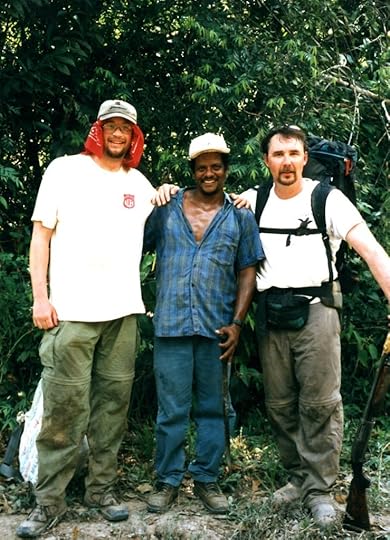

The next day--going back in

DUNGO IN THE JUNGLE

"Now the spoiler has come." Robinson Jeffers

They were poaching deer and drinking dark rum out of a decapitated spring water bottle, Dungo and his friend. In the front seat were two shotguns–Dungo's 12 gauge–he'd re-welded the barrel himself with bronze–and his friend Lilpo's 16 gauge that looked like a Civil War musket. In the back of the truck lay two rusted machetes (pronounced with two syllables–ma-chet–in southern Belize.) Lilpo thought he saw a light far down the trail and so Dungo drove in further over the bumps and ruts, though he didn't see it himself. But as they got closer, they were sure they made out two or three flashlights.

As it turned out we were the ones waving the flashlights. They stopped twenty yards from us and called out.

"Jake?" I yelled back. Jake was the name of the man who ran the research station we'd been scheduled to hike into that day. We'd been lost for several hours so I thought he might have come looking for us.

"No, it's not Jake, man," Dungo yelled back, already laughing. He pulled the truck up to where we stood.

I later teased my wife that she ran up to them as if they were Triple-A rumbling up the interstate: "Oh, thank God you're here! We're Americans, we have money!" My friend Mark, for his part, greeted the truck's arrival by lying down in the mud on the side of the road, the last of his energy spent. By default, it was up to me to play the part of the paranoid; I wasn't quite so sure we were being saved.

"You want a drink, man?" the driver asked me, holding out the rum.

I declined and began to explain our situation. The driver was a black man of medium height who told me his name was Edward, but that out here he went by what he called his jungle name: "Dungo." Dungo had the distinct look of an Australian aborigine–"What I am they call a 'Coolie' around here," he explained to me later when giving me an ethnic sketch of Belize; "Coolie" being a term for anyone with East Indian blood. He had a ready but wild smile, and a quick laugh. His friend Lilpo was taller–"A Creole," Dungo said the next day–and more stoic, but his rasta hat seemed to hint at pacifism, despite the jutting gun. I offered them twenty bucks American to drive us back to the nearest hotel, and soon Nina, Mark and I had all piled into the bed of their truck.

What we were doing out there in the first place was another story. Stick to the road, our host had told us before sending us off on our adventure, and so we stuck to the road. Stuck to it when it suddenly veered south, parallel rather than into the jungle; stuck to it when it meant wading through knee-deep water and waist-deep grasses, despite all the snake-warnings we'd been given; stuck to it when it began to weave crazily in and out of the jungle itself, despite the increasingly obvious evidence that it was leading us nowhere. "Snakes love leaf litter," our long-gone guide had warned us, but as the afternoon wore on leaf litter, specifically the perfectly snake-colored dead palm fronds, was all we walked over. It said everything you need to know that when a six foot diamond-patterned  creature the thickness of an engorged firehose lay in our path, we quickly dismissed it as "only a boa constrictor," shrugging off the largest uncaged reptile I'd seen in my life as if it were a gray squirrel.

creature the thickness of an engorged firehose lay in our path, we quickly dismissed it as "only a boa constrictor," shrugging off the largest uncaged reptile I'd seen in my life as if it were a gray squirrel.

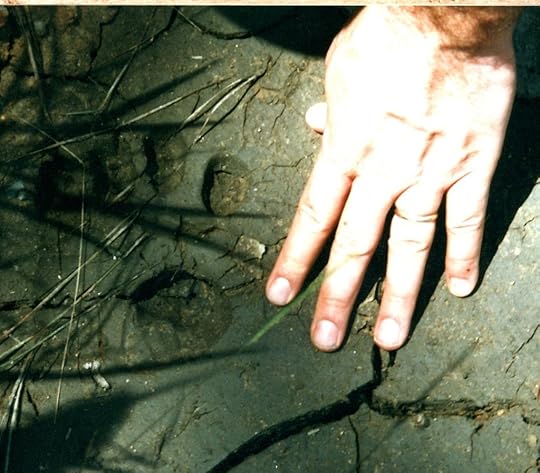

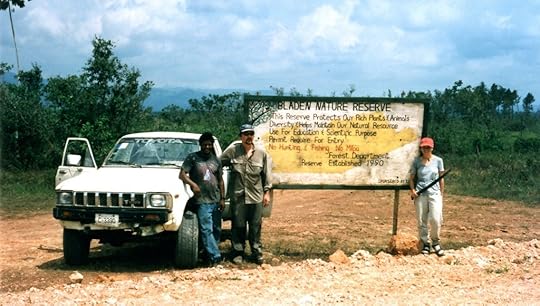

There were three of us hiking into a biological research station in the most remote jungle of Belize–me, a momentarily displaced New England nature writer, my wife Nina, also a writer, and one of my closest friends Mark, who, it was slowly dawning on me, wasn't quite the young, Ultimate Frisbee-playing jock I still imagined him to be, but was, in fact, an out-of-shape middle-aged man with pale skin never meant to be exposed to the equatorial sun. In other adventures–lost and water-less in the Utah canyonlands, carrying a burning crib (really) full of newspaper and kindling out of our home on Cape Cod–Mark had acquitted himself quite heroically, and he was by far the most survival competent of the three of us, having been given instructions by our former guide to "watch out for Nina and David." But this would not be his finest hour. By mile two of our hike into the Bladen Nature Reserve, the brown jays scolding down at us, he was already grumbling and stumbling across the pine savannah, the rain forest still some ways off, the Maya Mountains shimmering in the West. When we veered south he began to mutter about the idiocy of the trailmakers. In fact he was sensing correctly that we were going the wrong way, but I just wrote his warning off as more griping. He did perk up briefly when he saw the seven inch jaguar print in the fresh mud, pulling a camera from the knapsack that held

Jaguar Print

twenty-five pounds or so of photographic equipment that he wore like a papoose hanging off the front of his chest. But by the time we started wading through the muddy water he was all but finished, not even reviving when, after three hours, the track finally seemed to begin heading in the right direction. In retrospect I understand that he was suffering from heat exhaustion, and having since been leveled by it myself, understand what an effort it took to move those many miles while sick, but a the moment I thought him a slacker. More and more Mark began to take unannounced breaks, lying down right on the trail, even on the dreaded leaf litter itself.

My own reaction to his condition, and our predicament, was a fairly perverse one: I was transformed into one of those fanatic conquistador-type characters out of a Werner Herzog film, complete with crazed eye gleam, convinced that we needed to push further and faster into the jungle despite the growing evidence to the contrary. The dynamic between Mark and me had been similar for a while near the end of the time we'd been lost in Utah, when I, pumped on adrenaline, had waxed poetic about the glorious rising full moon that seemed to be leading us home and he had snarled back: "Fuck the Moon." In the jungle he barely looked up when I pointed out the swirling tornado of white and yellow–both pale and bright yellow with delicate white outlines–butterflies. He did manage to snap a shot of the boa constrictor, that, after posing for us, slithered politely off the trail, but when he sat down to rest again I decided foolishly that Nina and I should charge on without him. After another couple of miles the jungle closed in, the cahoon palms canopying overhead and the chatter of strange birds reverberating. The straps of our backpacks cut into sunburned and bug-bitten skin, slipping on a pool of sweat and slime. Nina called back to Mark and I blew hard on the whistle he'd given me, but there was no response. It was now past Four O'Clock and the sun would set at Six. Nina, the youngest and fittest of us, was also the voice of reason. "We can't just leave him back there," she said. "This path is going nowhere." I had one last surge of Herzogian energy and charged ahead for another mile to discover that she was right. The path simply stopped, swallowed up by green.

It was around this time, the sun starting to drop over the mountains, that we remembered that the most deadly of the snakes we had been warned about, the Fer-de-Lance, which was nocturnal and was likely just yawning itself awake. Later a herpetologist would assure us that the Fer-de-Lance, or Tommygoff as it was known locally, was not "aggressive," as the guide books all claimed, but was in fact merely territorial, but at the time we knew nothing but what we'd been told. Nina and I turned around and began to backtrack out of the jungle with a new and desperate energy. As it grew dark we walked even faster, crunching over fallen logs and occasionally tripping, leaf litter be damned. By the time we got back to Mark it was clear he was not merely malingering: he was sick, a case of heat exhaustion at the least, and I'd never seen him so lifeless. We lugged him to his feet, and Nina

Hones accepts death

Nina doesn't. (But has been happier.)

took his camera pack, divvying the contents up between the two of us. We set short term goals, the first and most urgent being getting out of the jungle before dark. When that was done we briefly considered setting up camp, and began gathering wood and taking our packs off, but that idea was squelched by the look on Nina's face and the notion of spending a tentless night with the jaguars and fer-de-lance, not to mention the bugs. And so the forced march continued, the next goal being getting back to the water we'd hiked through. In a day full of worst moments my very worst might have been sloshing through two feet of brown water in the dusk, smacking a large stick in front of me to ward off snakes, while my boot was sucked off into the muck. I dug the boot out, and we plowed through the water, but once we got to the other side we all collapsed in the hump of mud between two deep tire tracks of water.

On the back of Nina's pack she still carried the pineapple she'd strapped there that morning. We considered slicing it open, but finally decided to save it for dinner. By that time we'd been hiking seven and a half hours and were out of water, but Mark's bottle of warm Coca-Cola gave Nina and me new life as the light faded and dozens of swallows carved up the insect-filled sky. At the point where we'd made our wrong turn we stopped and listened to the wild mockery of laughing falcons, a noise that my field guide rightly described as being like "maniacal laughter."

It was dark by the time we'd turned back West, with three miles to go to the highway. "Highway" here is a loose term to describe a bumpy dirt road with little traffic. That morning we'd been driven two hours from the biological camp where we'd been staying and dropped off at the sign for the Bladen Reserve. We had no assurances that getting out to the road would be our salvation, or even a particularly good idea, trading the reptilian threat for the human one, but Nina was now sure of one thing: she wasn't sleeping outside, at least not in this place. So we trudged on, our flashlights reflecting back the eyeshine of our audience, the many animals watching us from the sides of the trail. With the sun down, Mark mustered up a new surge of life and was now moving at a steady clip. I walked out front, smacking my stick on the trail, channelling some ancient tribal song meant to ward off snakes–"Snakes begone…Snakes go away…We kill snakes"–and singing loud, bad renditions of "Rumble in the Jungle," "Jungle Love," and, for no particular reason, "I Want to Rock and Roll all Night (and party every day)."

It was in this tattered, ridiculous state that we suddenly thought we saw a light, suspecting wrongly that we'd made it out to the highway. After a second of readjustment, we realized our mistake. The light was coming down the trail itself–headlights, we saw now. An old battered truck was rumbling toward us.

* * *

We must have looked ridiculous as we lay there in the bed of Dungo's truck. It was a scene I later tried to draw. Mark lying down flat, all 6'4″ of him, his head by the tailgate resting on his pack, next to an uncovered cooler full of fish, snappers that Dungo had caught in the Monkey River earlier that day. Nina up by the cab unknowingly leaning on Lilpo's machete as we bounced out along the trail, with me next to her, sitting on a bag full of corn and leaning in the window to the cab, keeping up a steady stream of conversation with Dungo, still not entirely sure if he was friend or foe. Maybe I'd read too much Hemingway as a teenager, but I slipped Mark's fillet knife out of his pack and under my belt as I crouched and leaned into the small window. We discussed the various hotel options and then Dungo said: "We just got to go drop Lilpo off at his farmhouse first." They talked in Creole for a minute while I tensed, imagining a long dirt road and our executions by shotgun. I suggested we head to the hotel first instead.

"No man," Dungo said. "It's right on the way."

And it was. After we'd dropped Lilpo off, and continued down the Southern Highway, I relaxed and gradually began to see Edward for what he was: a generous, and exceedingly gregarious, man. I took the pineapple we'd carted in off of the back of Nina's pack and sliced it with the filet knife. You haven't eaten a pineapple until you've eaten one in the tropics, and this might have been the greatest pineapple ever. Mark, Nina, and I ate it all, slice after succulent, dust-covered slice.

We drove to Independence, a small town of dirt roads and shacks with corrugated tin roofs, many of them blown off by the hurricane back in October. A scrawny dog with low-hanging teats jogged down the middle of the road as if interested in a game of slow-motion chicken, swerving out of the way after Dungo hit the horn. We pulled into a cinder block building that didn't look like a hotel, but Dungo took care of us. Soon he'd helped us carry the bags upstairs, helped me cut a deal for less than the usual price, and told us we could find him later at the bar across the parking lot. Even before we got lost our trip hadn't been a very tourist-y one, mostly hanging out with ornithologists and botanists, but now, in a perfect counterpoint to the day, we discovered that the "Hotel Hello" was the single most American place we would stay. The room had two queen sized beds; it was air-conditioned with cable TV and, for the first time that trip, hot water. Mark lay still but shivering in one of the beds for a while, but began to stir after about a gallon or two of water. I brought up a plate of fried chicken and soon we were lying down on the beds, admiring our torn up feet, and gorging on chicken, watching "Blind Date" and "Rendez-view" on the tube.

My feet after

The bar I found Dungo in was equally modern. Five Belizean and one white English Banana sales rep were staring up at Schwarzenegger in "True Lies," cheering on the preposterous closing helicopter scene. A poster called "Ten Ways a Beer is Better than a Woman" hung on the wall. Dungo slapped me on the back and began to tell his barmates about our escapades. I admitted that I hadn't been sure at first if Dungo was there to kill us or save us, and everyone laughed. Over the next hour I bought us each three Belikins, the national beer, and soon we were re-telling our jungle adventures with the over-hardy air of drunken camaraderie. Like me, Dungo was a talker, and he knew everyone in the bar. Soon I'd learned about his career as a truck driver who sometimes drove up to the U.S., his days as an apprentice in the bush, his plans to expand his home for rentals, and the hurricane's disastrous effect on those plans. In the course of that hour I asked Dungo if he would be our guide for the rest of the trip, and he agreed for a reasonable price.

We were in business.

TO BE CONTNUED

We return to the scene of the crime the next day.

February 15, 2012

Rock Lit 101 (or: Rock and Roll for English Majors)

[Today's guest blogger is Mac Bates, who writes about Rock 'n' roll on his website All Those Wasted Hours. He's Bill's brother in law, and lives in Snohomish, Washington. The portrait is by MacKenzie Brewer and Mac's daughter (Bill's niece), Isabella Bates. Mac is an English teacher, mountaineer, record collector, and author.]

#

ROCK LIT 101

As a teenager besotted by rock and roll, except for the one night when I sneaked into my parent's liquor cabinet and sipped my way through a little vermouth, a little sherry, a little drambuie (A note to the kids: Do not try that at home, trust me), I wanted more than anything for my parents to love the music, which ran counter to one of the basic tenets of rock: we love rock and roll because our parents hate it. That Mom and Dad didn't hate it was a tribute to their open-mindedness; that they would sit down and listen as my friends and I debated the merits of Buckley vs. Jagger vs. Dylan was a tribute to their patience.

When Simon and Garfunkel first strummed "Hello Darkness, my old friend…" I knew I had found the music to bridge the generations. Paul and Artie were literate and no adult could deny their scholarly chops. I mean, "She reads her Emily Dickinson and I my Robert Frost." Literary up the wazoo was they. How could my parents not take to the guys? And they did. A few years later they became McGovern Democrats. Coincidence, I think not.

Rock and Roll has always had a literary/artsy side: "Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news, just like Romeo and Juliet and one pill makes you smaller and Father, I want to kill you. Mother, I want to…(rolling drums) AAARRRRRGGGGGH!" (Morrison must have been a pretentious twit in bed.)

As much as I wanted to kick out the jams, motherfuckers, I also wanted rock and roll to be recognized as art. As a result I jumped all over pretentious posers: Ars Nova, The New York Rock Ensemble and the Nice. Somewhere in my album collection I have the Electric Prunes "Mass in F Minor" and Chad and Jeremy's "Of Cabbages and Kings." Execrable!

In the '70s I stopped trying so hard and was happy when I stumbled across the occasional literary allusion. Steely Dan comes to mind.

I believe that writers want to be rock stars and rock stars want to be writers. Writers have on occasion teamed up with rockers to collaborate with varying degrees of success. I happen to be one of the few people who liked the Ben Folds-Nick Hornby album. Rick Moody is a member of the Wingdale Community Singers, and I know that Sam Shepard played drums for the Holy Modal Rounders. Patti Smith was a poet who became a rocker while John Lennon was a rocker who wrote poetry; so did Jewell. Whoops, I've said too much, I haven't said enough…Little known fact: James Joyce played hammered dulcimer on early Chieftains' albums.

This week I have put together my rock and roll literary anthology. Some on the playlist are obvious, others not so much.

Shakespeare's Daughter–The Smiths

Lorca's Novena–The Pogues

Song for Myla Goldberg–The Decemberists.

The Decemberists' Song for Myla Goldberg refers to the author of The Bee Season. I get all those bee novels mixed up.

Wuthering Heights–Kate Bush

Mother Greer–Augie March

I chose Augie March for a number of reasons. They have a literary rep. They take their name from a Saul Bellow novel and the song is sort of about Germaine Greer. And I need to listen to them more.

The Perpetual Self, or What is Saul Alinsky For–Sufjan Stevens

I had to throw in Sufjan's ode to Saul Alinsky, the much maligned activist and writer, and a hero of mine in the day. Okay, now I need to rant here. I am so pissed off at the Glen Becks and Sean Insanitys of the world who decided that doing right by the working stiff in America is somehow not only communist but almost satanic. Saul Alinsky has been dead for decades and those dickheads have the temerity to jump all over him as if he was Adolf Hitler. Fuck you Glenn Beck. Saul Alinsky was a supremely principled man, something you would never understand, you self-aggrandizing prick. I am now taking a deep breath, but fuck Glenn Beck!!!!!! (Notice, I used multiple exclamation points.)

Big Sur–Jay Farrar & Ben Gibbard

Big Sur by Jay Farrar and Ben Gibbard is from an album tribute to Kerouac's novel Big Sur.

Cloud Song–United States of America

Cloud Song by the good ol' US of A takes the lyrics from a Blake poem. I was in love with them in the late '60s and using a Blake poem gave them an intellectual cache–me too.

On the Road–Tom Waits

Romeo and Juliet–Indigo Girls

Rapture–Laura Veirs

Rapture by Laura Veir alludes to Basho and Virginia Woolf. And, as a side note, even though this is not on the side–work with me here–Laura Veirs is a national treasure. Will you trust me on this one?

Rexroth's Daughter–Joan Baez

Alexandra's Leaving–Leonard Cohen

Alexandra Leaving by Leonard Cohen is based on a Constantine Cavafy poem (probably the most obscure reference in the bunch). And I was introduced to Cavafy at an Outward Bound instructor training in 1979 by Don "Man" Peterson, a legend in his own mind. Somehow, I was supposed to become a better instructor by understanding not only Cavafy but Martin Heiddiger. Okay, is there anyone out there who can make heads or tails of Heiddiger? Swear to God, Heiddiger and Cavafy never came up during my years in the hills. But somehow I am glad that Don "Man" pumped those dudes into my brain. He also suggested at the end of our first OB trek that we have the students kill a sheep and roast it over a campfire. WTF?

Star Me Kitten–R.E.M.

Star Me Kitten is read/sung by William Burroughs. Is this a Burrough's piece? If it isn't, good on you REM for having the B man read your song. Can you imagine the dinner table conversation between Burroughs, Ginsberg, Kerouac and Regis Philbin? For the ages!

Sometimes a Great Notion–John Mellencamp

Frankenstein–Antony and the Johnstons

Moby Dick–Led Zeppelin

Just be glad I didn't include The House at Pooh Corners and Starry Starry Night. (Yeah, I know it's about Van Gogh, but it sucks to high, high heaven.)

******

There were a number of songs that didn't make the cut: Even Cowgirls Get the Blues by Emmy Lou Harris; Virginia Woolf by the Indigo Girls; The Ghost of Tom Joad by Bruce Springsteen; Frankenstein by Edgar Winter's White Trash; and any number of songs by Talib Kwelli, who references, among others, Dante, Octavia Butler, Brett Harte, Voltaire and Kurt Vonnegut. And, of course, Sugar Sugar by The Archies.

My blog partner, Jonathon Cowan, had a completely different take on literate rock and roll; he found the soundtrack for his favorite novels. Our musings on all things rock can be found at www.allthosewastedhours.com.

Bad Advice Wednesday: Beware to Com-PARE!

Dismissal at my daughter's elementary school is staggered by ten minutes, with the younger kids leaving earlier. Hadley leaves at 2:30, and on the rare days I get there early I sit out front and wait with the first graders. The other day one of them – we'll call him Johnny, which I'm reasonably sure is not his real name – was in a bit of a state. While his classmates sat quietly on the front stoop, he marched up and down the sidewalk as if he were orating . "I'm so mad at Bill. I know he's had three play dates with Dave, and now they're having another play date this weekend." Johnny was wonderfully unselfconscious about his jealous frenzy, the way only people under the age of six can be, and he didn't mind at all that his entire social world could hear his griping. It was time for Ms. Rennie, the first grade teacher, to intervene.

Ms. Rennie was Hadley's teacher last year and I Love her so much that I had to capitalize the word. She was born to teach young children: wonderfully kind and serene, with a soothing and melodic voice, but also with an almost mystical ability to impose order. I watched her stride across the sidewalk, place both hands on Johnny's shoulders, kneel down and look him in the eye.

"Johnny," she said, in her calm and musical voice. "We spoke about this yesterday. What happens when we com-PARE?" She spoke the last word in two distinct syllables, with a rising, drawn out lilt on the last. It sounded ridiculous and significant at the same time. Johnny cocked his head. The stress on that last syllable seemed to ring a bell.

"When we com-PARE," Ms. Rennie all but sang, "we start to feel bad."

Johnny nodded, recognizing the simple truth in that statement, or else properly hypnotized. He took his seat quietly with the others.

If you're a writer, you can easily see where this is going. We all have that person – or in some cases multiple people – whose accomplishments can seem upsetting when we com-PARE them to our own. I remember once, before I'd published a book, my husband and I were invited to a dinner party. David was a published writer at this point, as was every other person invited to the party, and our hostess had lined up everyone's books as a centerpiece on the dining room table. "Nina," she said, when she saw me notice. "I should have asked you to bring one of your literary magazines so we could have included you!"

I pictured all those beautiful hardcover books beside one of my battered old copies of Kinesis or Atom Mind II, and felt very glad that I hadn't brought one along. Years later, I sometimes find myself faced with the achievements of acquaintances or even friends, and I feel the same effects of that original visualization. I feel inadequate. I feel bad.

You do it too, right? You feel fine about your work, proud of what you've done, and hopeful about what lies ahead. Then all of a sudden, out of nowhere, you hear someone else's bio, with all their Pushcart Prizes and New York Times Notable Books and Starred Reviews in Kirkus, and if you were six years old you might just march up and down the school pick up line, waving your fists and complaining to everyone and anyone about the injustice. Instead you do what grownups do, which is fret, and doubt yourself, and wonder why you ever got into this ridiculous business in the first place.

And the answer? It's not a business. It's an endeavor and a calling, and you chose it because you love to tell stories, and you believe that stories matter. You know that life without art would be unbearable, so you want to do the brave thing, the right thing, and contribute some creation of your own.

So in other words, today's bad advice is a reprise on an impromptu lesson taught by a wise first grade teacher. Next time that particular and paralyzing darkness descends, try to hear Ms. Rennie's calm and musical voice in your ears. Consider it a rhetorical question, but pose it all the same. And then get back to doing the work you were born to do.

February 14, 2012

Skiing the Beach (Redux?)

We are getting senile here at Bill and Dave's, and neither of us is sure if I have posted my movie "Skiing the Beach" before. I probably have……but here goes again anyway: Skiing the Beach. (It's about how I stuck to my northern exercise routine even after moving south.)

We are getting senile here at Bill and Dave's, and neither of us is sure if I have posted my movie "Skiing the Beach" before. I probably have……but here goes again anyway: Skiing the Beach. (It's about how I stuck to my northern exercise routine even after moving south.)

And then there's the piece below, which, to the best of my knowledge, is the first essay inspired by a Youtube video….

SKIING THE BEACH

Over the last three months I have become the freak of my Southern neighborhood. I am the guy of who skis the beach.

It started one day when I was jogging. At forty-four, running at any speed is not a joint-friendly enterprise, and I feel the slam of every step in my achy knees and partly torn rotator cuff. For this reason, I was running, as I always do, along the water, hoping the sand would serve as shock observer. But even with sand softening the blows, jogging was drudgery, and for about the hundredth time I felt displaced in my new Southern home, longing for mountains, for snow, for the north. And for cross-country skiing, since its remembered velvety athletic rhythm, glide-push-glide, seemed the opposite of the trudge-slam-trudge of my present.

It was then that I glanced down at the sand close to the water, right where the waves licked and not ten feet from where I jogged. The sand looked slick, slightly wet, flat—and invitingly snow-like. Not heavy snow of course—that was higher up where folks put their beach towels—but packed snow like a cross-country trail that had been skied a few times. And then I thought "Why not?" My old skis were back in a storage locker in the north, but my birthday was coming up. When Nina asked what I wanted, she was surprised by my answer, but went ahead and placed the order anyway. While I was waiting for my new Atomic RC-8s to arrive, I did some on-line research. I remembered that my fellow nature writer, Bill McKibben, had written an entire book on cross country skiing, and had many contacts within that world. Through McKibben, I learned that there were other beach skiers out there, and that one of them was no less a name than Bill Koch, winner of a cross-country silver at the 1976 Olympics, still to this date the only American Nordic medal-winner. I read of how Koch had moved temporarily toHawaiiand had drawn stares from the other people from his flight when he picked up his skis at the baggage claim. For years, before moving back to his nativeVermont, he skied the Hawaiian beaches. "The darn stuff has lots of glide," he said. Koch inspired other sand skiers, including the University of Northern Michigan ski team, who train on the shores of Lake Superior.

My own skis arrived and, as McKibben recommended, I waxed them with glide wax (the sort you would use for very sticky snow) and sprayed them with silicon to further cut down on friction. For the next month, I would consult my tide chart, looking for the ideal low when the flats sprawled out, and then carry my skis over my shoulder the two hundred yards from our house to the beach. Of course this drew stares, and I started to prefer the colder days when fewer people were out, but even on the relatively crowded days it didn't stop me from plopping down my skis on the low tide sand, pulling the pole straps over my gloveless hands, and pushing off. And there it was: the glide-push-glide I'd been missing so. Sure, the glide wasn't quite as glidey as on good snow, but not bad, and the rhythm was there, the exertion of pushing with the arms and kicking with the legs, and my old knees were happy to be pushing forward and not slamming down.

* * *

Skiing the beach is a metaphor, of course. But a metaphor for what?

Adaptability is one possibility. My unofficial ski coach, Bill McKibben, wrote his classic book on global warming, The End of Nature, almost twenty years ago, but the mainstream press and politicians are only now gradually, and reluctantly, beginning to admit that the threat is real. When I sent McKibben the news that I was beach skiing he replied enthusiastically. "We've had almost no snow inVermont this winter," he wrote. "So your news gives me hope. Pretty soon we all may be skiing the beach."

On a more personal level I see beach skiing as a way of trying to use my old northern tools to place myself in the South. Those tools include walking, writing, and getting to know my neighbors, both avian and human. That these attempts are only sporadically successful, and often comic, does not make the symbol less apt but more.

Beach skiing is absurd but so it seems to me is this whole uncertain process of being alive. "For us there is only the trying," wrote T.S. Eliot. For a long time I was under the sway of writers like Wendell Berry and John Hay, and believed that if I found the right place to live on earth my life could have a new certainty, a new calm, a new magic. These two writers spoke of the need to marry your home place, and of the rewards that could be won if we truly committed to that place. But my life has taught me something different. I rarely slow down, let alone settle. I think I know where my home place is but I just happen to live a thousand miles away from it. I don't have much choice but to learn how, in Keats' words, "to be in uncertainties." Uncertainty, it seems to me, is the lesson life pounds at you again and again. The landscape never stops shifting.

Maybe that is why over the years I have developed a philosophy that is somewhat at odds with my nature-writing brethren. I am full of admiration for those who manage to root downward in this increasingly rootless world. We live in a time of exile and displacement: and rootedness is a radical and exciting response to this modern crisis. But I can't help but hear a slightly ministerial tone in much of the literature of "finding home." It reeks of virtue. Or to put it another way, I admire these writers when they stick to telling their own stories. It is when the element of should slips in that they are on less firm ground. Because the fact is that many of us find ourselves in places that are not home, many of us live in geographical turmoil, many of us have little chance to truly root. And in this case maybe the better question isn't "How can I get out of this uncertain state?" but "How can I exist in it?" Or put another way: Rootedness is one answer, but accepting one's rootlessness is another. Or yet another way: I am happy for Wendell Berry that he gets to live forever in Kentucky. But I, like most of us, live in a state of confusion.

* * *

Skis are not just metaphors. They are also a means of locomotion. The best skiing day came in February when sudden frigid temperatures hit. The wind chill brought it down to about 5 degrees, which made it feel like home. The beaches were completely empty: not a Southerner for miles. The wind scraped down from the north, sending swarms of sand in front of it, giving me the beach to myself so I could ski without feeling silly (or too silly). But for all that, with the sun shafting down into the suddenly darker sea, it was a beautiful day, and, even better, the birds were out in force. I skied the beach for a couple miles, getting a good sweat going despite the cold, and then stopped to watch the birds.

What I saw was a true frenzy. There must have been 500 gulls in the foreground, and hundreds of pelicans, and beyond, out over the open sea, thousands of northern gannets. To watch a single gannet dive is a wildly impressive feat: a bird suddenly pulls in its wings and drops out of the sky like a spear thrown. To see a dozen drop at the same time is to experience amazement: they look pulled from the sky toward some invisible underwater vortex. But now, to see dozens dive each second was almost too much. Boom. Boom. Boom. You couldn't help but yell out loud when they hit. I was caught up in the sheer electricity of the action, and in the day's wild, wintry feel. A new squadron of gannets flew in every few seconds, pure white with black wingtips, easy to distinguish from the gulls by both shape and color against the darker clouds. They continued to dive in rapid succession, and not just straight down in their usual style. I watched forty or so birds dive into the same wave at the same moment, angling down as if riding on the godbeams of sun that shafted down out of the blue clouds. Slicing in: boom, boom, boom, boom. How did they manage to not collide with each other? I know for a fact their necks are a weak point; I have seen them on the beach with those necks broken after storms. But certainly on that day fear wasn't slowing them down.

The birds' energy was contagious. The sight left me jangling. I felt renewed energy, renewed ambition, renewed passion. I hurried home and up to my writing desk. Ready to dive.

* * *

I skied through the winter but with the spring the beaches became more crowded, and I began to feel self-conscious, especially once the heat forced me to ski in my bathing suit. One day a friend walked the beach behind me and told me that when I skied past every head quickly turned and that cell phone cameras were held up high, and that when he passed by the same groups a couple of minutes later they were still muttering about "skiing" and "the beach." By April the beach had started to fill, and I had grown sick of the gawkers. It turned out that I quit theCarolinabeaches about the same time the gannets did. Around Easter I put my skis away for the summer and decided that, just as in the north, the colder months would be reserved for skiing. I'm sure that by mid-summer I will be looking forward to next fall when the beaches will start to clear, anticipating the coming ski season. I can't wait to get out there again next year, to sweat in December as I slide over the sand and to watch the diving gannets and embroiled surf. Since moving south, I have often longed for the North, and more than once I've thought "I don't belong here." But, oddly enough, it was during those moments on the beach, while practicing my strange new sport–itself a perfect symbol of displacement—that I started to see that maybe this place wasn't so bad—it has an ocean after all—and found myself thinking "I like where I am."

It's not that simple of course. You could make a good argument that skiing works better on snow, that there is a desperation to my attempts to place myself. Still, I look back on that gannet day in February as a great one. You could argue that après ski is the best part of ski, and I remember the after of that day as well as the during. Once the exertion is over, once the cold and minor miseries are over, once you are safe and warm, face stretched tight with windburn, drink in hand, only then do the disparate, fragmented moments take on a cozy unified whole. The past tense smoothes out rough edges. Afterward cold hands seem merely romantic, not distracting. It's funny to listen to people speak glowingly of camping trips that they complained throughout. Which is also one of my problems with nature writing in general. The belief that heaven on earth is possible, that human nature can be somehow purified. This is dependent on nostalgia (literally a "home coming") for a time that never existed. Maybe the belief that we all have one true home is a kind of pastoral masochism, like the follower's belief in the ONE PERSON, here transposed into theONE PLACE. Maybe the most important thing to remember about Thoreau's cabin in the woods was that he left it, that he had his other lives to lead. And it is also important to remember that he never owned that land to begin with. That he was temporarily squatting on Emerson's land.

But as I rested after my big ski I felt happy enough, sitting in my rocking chair on the deck in front of my unit in the woods, my hand wrapped around a cold Harpoon IPA (still clinging to theBostonmicrobrew). That happiness was dependent not just on the much-hallowed "present moment," but on the past—the adventure I'd just had—and the future—the anticipation that my daughter would soon be home from pre-school. Earlier in the year I'd judged a nature writing contest and grew so tired of the phrase "being in the present moment" that I finally threw one of the books across the room. I think that farm animals do a fine job of being in the present moment. Humans not so good.

That day I took a break from my beer to walk downstairs and hose off my skis. Sand in your bindings is one of the great problems with skiing the beach. I carried the poles and skis back up to the deck and rested them behind me against the deck wall. Then I plopped back down in the rocking chair on the deck. If I squinted I could ignore the gold brick, elementary school-style building to my north and look out across the water toward Masonboro, the undeveloped island to the south. There I sat in post-nordic glory, somewhat ridiculous, sipping my afternoon beer, my mind both leaping to the future and jumping back to the past, but also mildly pleased with the present, half in love with where I was. It was not a perfect moment, not a pure moment, but it was a fine moment nonetheless. It's what I had and where I was.

Perhaps all my worry about how to place myself has been for naught. Perhaps next year I'll get a job in the North and move back to Cape Cod and yell "Eureka!" Perhaps Hadley and Nina will find true joy and peace in that new home, and perhaps I'll stop my fretting and learn to be in the present moment, dancing Zen-like through my halcyon days. Perhaps then I'll write long letters of apology to my old heroes, John Hay and Wendell Berry, and settle our lovers' quarrel over place. I'll grow my beard long and prophet-like and burn my cell phone in a solstice bonfire and build a cabin in a glade for my girls. Then perhaps I'll retreat to a mountaintop (or a hilltop since we are talking about the coast) and return with tablets in which are burnt the eco ethics for the coming green century.

Perhaps. Or perhaps not.

The truth is I have no idea what will happen next.

Until then I will keep skiing the beach.

February 13, 2012

Hostages

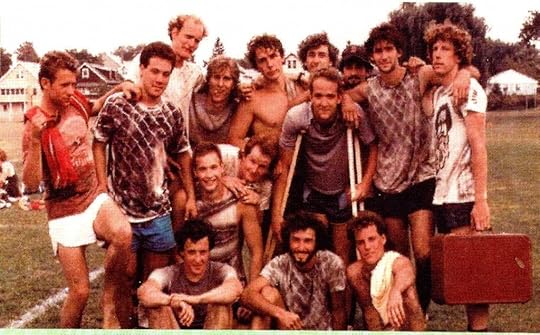

So, much to my surprise, my "Ultimate Glory" post of the other day has spread around this here inter-web, closing in on a couple thousand viewers. It occurs to me that the post might have benefited from a few more photos, but I don't have many from the old days, at least in places I can get my hands on. I did manage to scan the picture below, which came out of the book, Ultimate: the First Four Decades by Adam Zagoria and Pasquale Leonardo.

These are the Hostages mentioned in the essay. (Though the photo is missing a couple of very important characters.) P.S. The guy on the far right with the suitcase is a frequent commenter on this blog. (Not me.)

February 12, 2012

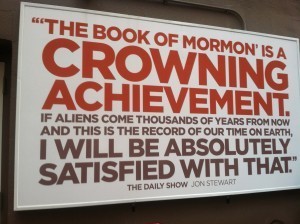

Things I Saw in New York

February 11, 2012

Getting Outside Saturday: Field Notes on My Daughter

We moved from Cape Cod to Carolina about eight and a half years ago. I wrote this soon after our first school year in the South ended, when we returned to the Cape in June. It turned out we weren't the only ones with a new baby and this is the story of how we interacted with another pair of parents and their off-spring. It was originally published in the great journal Isotope. Long may it live!

We moved from Cape Cod to Carolina about eight and a half years ago. I wrote this soon after our first school year in the South ended, when we returned to the Cape in June. It turned out we weren't the only ones with a new baby and this is the story of how we interacted with another pair of parents and their off-spring. It was originally published in the great journal Isotope. Long may it live!

FIELD NOTES ON MY DAUGHTER

1. Fox

During these joyous days back on Cape Cod I am taking field notes on both the local foxes and Hadley. Hadley is now just over a year old, a completely different animal than the one who moved south: a walking, talking, gesturing hominoid. Last night she rode my shoulders to the beach, and we found that a fox family had built a den in the seawall rocks. Hadley pointed at them and said "cat," the word she is stamping on everything these days. Still, if her term for them was not entirely accurate, she was close. The two kits, their legs covered with black stockings, ambled right up to us, and she could barely contain her excitement. Meanwhile, I tried to maintain my scientific sobriety, taking notes on their black eyes, their white-tipped tails, their foolish trust.

Hadley's physical development, like those of chimps and apes, her closest relations among primates, is relatively slow compared to other animals, these foxes for instance. In humans, physical growth, height and size, is retarded because time is required for us to learn the complex, symbolic and ever-changing world of our species. But the mental growth is wild. You see it in Hadley's eyes and her hands and in her intense interaction with the physical world. Not long ago I taught her how to snap, and now she moves around the house going at it like a Beat poet. Her prose poem of course is made up of that one obsessive word, "Cat," though she inflects a hundred emotions from the sound. The other night she woke up from a dream and said quite clearly: "Cat. A cat." The alliterative and vaguely homonymous "Cow" has also leaked out, so you get the feeling that a hundred other words are gathering, readying, almost a cloudburst.

Because I have the foxes handy for study, I've decided to take out some books and do field work, watching the kits grow. I'd also like to try to record more exactly and objectively the changes in my daughter as she heads into her second year. Things happen fast in an infant's world, and since growth is by definition change it is therefore one of the most stimulating subjects for study (outside, perhaps, birth.) The human mind, after all, is conditioned for growth—for novelty. No wonder it's absorbing to watch an infant turn to toddler and toddler to child. It holds the same appeal as gambling or drag racing. We are pre-wired for speed and change. Taking field notes on a middle-aged man wouldn't be nearly as interesting.

If explosive growth always captures the human imagination, then this is the appeal, not only of childhood, but of this time of year, of the approaching solstice. Solstice is not just an announcement of summer but also the culmination of spring, and growth is spring's great theme. Right now the birds sing before dawn while the cup of the year fills to the brim with green. Nothing becoming something. The small blooming large. Opening. Bursting. Overspilling.

2. Toward Solstice

This morning I am down at the rocks at 6 with my coffee. All four foxes, mother and three kits, gradually emerge from the den. They gaze at me, curious, with their black eyes. Apparently I am not perceived as much of a threat for soon they are lazing on the rocks near me while I sip my steaming drink. They have habituated to me in no time. We all loll together, the kits resting their heads on their paws. They scratch their ears, leaving spikes of orange hair standing straight up. Finally it's time for exercise and the three kits tear after each other on the sand. At one point the smallest of the kits decides to play hide and seek. All I see is two triangular oversized ears behind a beach rock.

Back at my desk I learn that foxes are, according to my books, "a living symbol of intelligence," made out in myth to be wily, clever, sly. This is in part, from our human point of view, because of how difficult they are to trap (though this beach family would make easy prey.) One book, The World of the Red Fox by the impressively named Leonard Lee Rue the Third, waxes poetic when it comes to the fox's coat: "Its coat, captured by the sun, takes on the tints and highlights of burnished gold and copper." And: "The wind playing in its fur, as if passing through a summer wheat field, causes a constant change in its shadings and hues. These are subtleties that the eyes can capture but the pen cannot." It's true that watching the rust-colored family on the beach is a little like watching a fire, oranges and reds flickering. As with all red foxes, the ends of their tails look like they have been dipped in white paint. Their ears, cheeks, throat and chest are white, too, while the nose, back of ears and their leg stockings are black. They are also, and I say this as scientifically as possible, unbearably cute. The main job of a newborn, whether human or not, is to create a deep attachment in the adult, an attachment that motivates the adult to do all the necessary work of parenting, as well as compromise his or her own life. It turns out that round faces and big eyes do the trick when it comes to creating this attachment. As Stephen J. Gould, among others, have pointed out, there is an evolutionary advantage to looking like a Disney character.

But back to fur. On the kits and their mother it is luscious, fiery, full. It also is responsible for the substantial appearance of these small animals. An adult fox actually weighs less than our cat, Tabernash, a former stray, and only a little more than our old cat Sukie, on average between eight and 11 pounds. According to Mr. Rue, a fox, once skinned, has a long lean body "like a miniature greyhound" and the "chest is small and can easily be encircled by a man's hand."

I record fox facts in my journal until 11 and then walk downstairs to find Hadley and head back out into the golden age of early June. We will spend the afternoon on the beach, before heading back home for naps. Then, when I wake up, I will grill chicken sausages for myself and my wife Nina and drink, I would guess, somewhere between three and five beers. After that it's off to sleep early—all in the same bed, still primate-style—so that I can get up before dawn and watch foxes again. Solstice is only three weeks away. And this, I tell myself, is not such a bad way to live.

3. Handy

With so many miracles of growth speeding toward us—the beginnings of language and locomotion to name two—it is easy to forget a more commonplace miracle, the one that helped our ancestors survive the jungle and then far beyond the jungle: hands. It is this transcendent tool that led to all other tools. We think that our brains and our words separate us from the rest of the animal world, and it's true that complex verbal language is our greatest distinction. But so much starts with hands. One difference between Hadley and the fox kits is that she "brings her food to her face while they bring their faces to the food." True, a raccoon does the same, as well as all her fellow primates, but the ability to hold and study objects, to place and move them, to manipulate the world in subtle ways, was our first great advantage. How convenient—I'll resist saying "handy" here—that the same equipment that allowed us to climb trees also had so many other uses once we came down onto the plains.

To watch the first year of an infant's life is to see that hands are our first language. Not just the Kerouac-like snapping that Hadley accompanies her Cat poems with, but all the gesturing and pointing and handling that have been one of her central preoccupations for the last 12 months. She has been grasping and letting go for a while and now she is suddenly throwing and switching and turning and flicking. She is a miniature Houdini, untangling and opening. These are skills sets she shares with chimps and gorillas, though soon, as the unfolding of language begins, she will put some distance between herself and her fellow primates. Yes, chimps have been taught sign language, gorilla society is complex and vervet monkeys have different "words" for snake and eagle that come out in their alarm cries. But what is happening now in the human brain is unprecedented in the animal world and as close to miraculous as anything in nature. While in some ways I believe that we humans are just another animal, it would be the species-wide equivalent of false modesty not to acknowledge that here is something that makes us remarkable.

The brain and mouth work wonders, not to mention the frontal binocular (color) vision of our eyes. But those hands! Curling, gesturing, cupping, pointing, touching. In Apes, Monkeys, Children and the Growth of the Mind, Juan Carolos Gomez writes:

"The decisive evolutionary advantage of primate hands is their versatility…The primate hand is an organ specialized in having a general function—grasping—useful for a variety of adaptive purposes. The case of the hand illustrates an important feature of the primate order: primates specialize in not being too narrowly specialized!"

In this way, hands allowed us to become what we are: the great generalists, the great adapters, of the animal world. But the hands are not only grasping tools:

"Hands have their own ways of sensing the world: they are equipped with sophisticated organs of touch. Primate fingers possess highly sensitive tactile pads that provide the brain with precise information about the textures and shapes of objects."

So there it is. In our history, not just as food gatherers, but as information gatherers, hands were a primary tool. We used them not just to hold things but to map our worlds.

4. Morning

The first distinctive song this morning, at 4:26, is the upward whittling of the cardinal. At 4:44 the woodwinds join in with the mourning doves' hollow cooing. It isn't until almost five, 4:59 to be precise, that the hinged song of chickadee completes the symphony.

I am up early to write—just like the old days living on Cape Cod. I am reminded that for me the romantic image of the "cabin in the woods" is not necessarily about quiet and calm, about "relaxing" in nature. The cabin I like is Van Gogh's yellow house or Jackson Pollack's Long Island. For me the cabin is not a place of peace but the place where you make art.

One of the pleasures of writing essays is making connections, seeing how disparate things can form a circuit and how that circuit can electrify. It is not necessarily a pleasurable state, because there is too much going on, too much you need to "get down" before the state passes. It is rushed, intense, uncomfortable. I wake early not just because of the birds but because of that Christmas morning feeling of expectation. What will happen today? What unconnected things might connect? What circuits will be plugged in?

My own overexcited state is reflected in Hadley. Her cousins are here and she chases after them on the beach. My wife has been keeping a journal of Hadley's growth since she was born and yesterday's entry reads:

June 19

When Hadley sees an animal—the neighbor's Siamese cat, a little white dog on the street—she presses her head into its face. Just like Tabernash taught her. Deeply sweet and heartbreaking. She does it to Sukie too, and that poor old cat purrs and purrs.

It's been over a month since I last wrote in here – and what a month for Hadley. She presses the boundaries of delight, leaving glowing smiles and desperate heartache in her wake. I thought we were going to have to sedate Kim (her babysitter) when she left for home last Tuesday. These days with Addie and Noah are unbelievably fun and insanely exhausting – Hadley puts her every heart, muscle and bone into following them, playing with them, responding to them.

Walking: hard to believe she ever didn't walk. She runs, she dances, she stomps her feet, she jumps. Words she says consistently are Cat (of course), and now Kitty Cat, Cow, Cow Moo, Duck, Dog, Baba, Kim, and Noah. In the past two days she also seems to have said "No" and "More." And "up," possibly "down."

One aside: In Cambridge this week, five-year-old Addie asked her mother Heidi: "What do you think Hadley does when she sees God?"

Heidi said, "I don't know. Maybe she smiles?"

I guess it shouldn't come as a surprise that Heidi has a better relationship with/perception of God than I do, since my first thought was "Quake with fear."

As Nina points out, the long-expected blossoming of language has come. As Hadley discovers the world through language, repeating the journey of her species, I find it interesting that so many of her early words signify animals. Some naturalists speculate that language grew in precisely this way, because humans had to make distinctions—distinctions for hunting and protection—about the animal world around us. While I don't think Hadley is worried about either hunting or fleeing from predators, it is remarkable how much of her inner life, from her love of the Pooh books to the stuffed toys she grasps, revolves around animals. The naming of creatures and language are linked.

* * *

By six I am down at the beach naming animals of my own. Call me Adam. Or maybe not. Either way, I am a pretty rudimentary namer, labeling the fox kits #s 1, 2, and 3. Not romantic names, true, but anything I can do to make them less cute helps with objectivity. Yesterday, while walking down below the bluff, I came upon #2. I would say I startled him but that wouldn't be accurate. The sun was out and so were the intense silver and greens of the ocean and eel grass. It was a fall-ish day, the world silver-edged and crisp, whitecaps boiling the bay. I was just out past the rocks, and past where the people go, when the kit came ambling out from behind a rock. Lazy, tired, yawning, it cast a glance at me, but, far from running away, it just cocked its head. It then turned away, and, after a casual glance back, walked a few feet out of my path. On the way back I saw it again, but that only sent it about 10 feet off behind a rock. From there it examined me until I passed and then it walked back to its previous spot where it plopped down to nap in the sun.

This morning the other young foxes are equally lazy, lolling with their paws over the rocks near their den, while nearby a prairie warbler lets loose with an upward scale of Zs. After a while the kits finally roust themselves and start hop-pouncing on insects, getting on with practicing the business of being foxes. It's perfect, really, that kits are also called "pups" since foxes seem caught in some indeterminate space between the worlds of dog and cat. They are the most obviously feline of the canines, lounging and leaping through the world in a decidedly cat-like manner. Their cat-dog ears are great indicators of emotion, and they flatten them against their heads when afraid. They also lower their tails in dog-like fashion when threatened. And, like dogs, these pup-kits find nothing, as Rue III puts it, "as satisfying as a good stick." Rue has noted that they play all the usual games, tag and leapfrog and hide-and-seek, the play doing its grave work of preparing them for a life of hunting. In fact the more I watch them play the more satisfied I am with their canine classification. They roll and bark and growl and wag tails and occasionally grovel at each other's feet in submissive poses very similar to coyotes I have watched.