David Gessner's Blog, page 97

December 27, 2011

10 Bad New Year's Resolutions for Writers (Bad Advice Wednesday: The Holiday Edition)

1. Stop writing this year. Just quit. You can do it. Writing's an addiction.

2. Stop reading. No media. Nothing. Listen to the rain.

3. Quit your job and roam the planet going broke.

4. If you have to write, write stuff that can't be sold, then give it away on a street corner in Rome.

5. Sit and think, or just sit.

6. Invent a new medium, and for a while, be its best practitioner by far.

7. Take ballet lessons. Don't write about them.

8. Take a Bruce Springsteen or Joni Mitchell or Patti Smith song (or any other) and make a story out of it.

9. Sing this story.

10. Scratch very personal essays in the sand on long northern beaches.

December 24, 2011

Merry Christmas!

December 23, 2011

Mapping the Night Trees

It's been getting dark a little after 5 here. Or about two hours after it gets dark for Bill.

Hadley (my eight year old daughter) and I spent a night last week down in the shack making a map of the trees that line the opposite shore of our tidal marsh. Once the sun goes down they appear as black silhouettes across the horizon. We've been naming them, too. You likely won't have much trouble finding the "Poodle Head" for instance. Here's our map so far:

December 22, 2011

Winter Solstice

From my book Temple Stream [then as now, though the dogs are gone, and a new one in their place, pretty Baila, Elysia not only born since (her birth part of the narrative) but eleven years old!]:

From my book Temple Stream [then as now, though the dogs are gone, and a new one in their place, pretty Baila, Elysia not only born since (her birth part of the narrative) but eleven years old!]:

#

Winter Solstice

#

Starting as early as October, but more likely November in a given year [and not till mid-December in 2011], Temple Stream begins to freeze. Every day the ice changes, grows, shrinks back, advances.

#

And every morning the dogs and I hiked down there to have a look, and hiked down again each evening, just to see what had changed. Ice paved the way: the muddy parts of the path were thrown up in frost castles, delicate keeps and crenellations of dirt and ice that collapsed with a satisfying crunch underfoot. The kingfisher was quietly gone, the mallard pair, the great blue heron–all the late stayers had quietly movced on, no fanfare, only absence.

In the stream, pullucid ice formed up around rocks and alder roots, around the branches of strainers and sweepers. Alder tips that had dipped into the water with the weight of summer collected balls of ice that grew to knobs, crystal as fine as Victorian chandelier glass. In the extended cold snap we'd just suffered–a week or so with nighttime temperatures in the single digits–the knobs morphed into globes and rare platters, nymphs on dolphins, grew until they touched, the edge lace spreading till the filigree and figurines and beadwork of one branch or rock met that of the next, thinnest sheets of ice growing out into the quitet parts of the stream like etched panes.

Wally, his winter coat coming in sleek and long, his bull's chest thrust forward, his tail wagging high, was first to try the ice. He rushed down, saw that the stream had hardened, balked. After some expressive barking, he put a mighty paw down, tapping his claws where water had been. The offending ice didn't break immediately, so he scraped and scratched in outrage until it did, flipping up chunks that turned out to be textured underneath, intricate relief sculptures carved by hydraulic friction and the water's slight heat. Path cleared, heeless of the chill, exultant Wally splashed in among his own flaoting shards till he was up to his chin, drank as from a smashed chalice.

Desi was next. With his senior citizen's hard-won disdain for lesser minds, he found a place Wally hadn't sullied, tried the ice gingerly. Finding it sultable, he proceeded, mincing toward free water on tippy-tippy claws untrimmed. The ice sighed and he pulled up short, listened a long minute before his next brief steps right to the fine edge of the flow, where he took a cautious drink. The ice out there poopped and his ears flew up in alarm. He retreated, slow steps in reverse. The ice crackled and broke along minuature fault lines, and the good dog looked back to me for courage, straining every muscle skyward in an efffort to make himself lighter.

Night by cold night, the ice sheet thickened. Breezy conditions would have made a rippled surface, but we'd had days of cathedral stillness: window glass. And now snow: the ice was gemstone black, a portal to the booom, stream grasses still flowing under there, the familiar rocks and sands of summer arranged as in a display case or aquarium, one torpid minnow finning bast, then another. I stared into the world daily and lingered, thinking of the time long since that I'd had the luck of seeing a muskrat cruising under the ice.

By mid-December the stream was nothing but a channel, the thickening ice sheet closing in from both sides. I ventured out upon it behind the test dogs, sliding one foot then the other, listening like Desi for any sound of cracking, lingering over an ice-trapped oak leaf encrypted by the warmth of the sun in a perfect oak-leaf-shaped jewelry case, oak-leaf-shaped lid on top, oak leaf itself nestled several inches down, where it would sunbathe itself clear to the water, leaving just its shadow in the ice.

December 21, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: Writer, Edit Thyself!

Here's a few thoughts on editing your own work:

Here's a few thoughts on editing your own work:

1. "I hate it," isn't an uncommon reaction when returning to a piece of writing after a time away from it, just as "This is the greatest thing ever written" isn't uncommon when in the throes of inspiration. The trick is to come back to a piece with a mindset somewhere in between the two extremes. That is to come back with a "new head," calm, practical, aware that what you are approaching isn't either the worse or greatest piece of writing ever produced, but something that can be tackled, re-worked, improved.

2. It's easier to have a "new head" when there's actually another head. That's the reason that editors exist. You simply can't see everything yourself. Is there another individual, hopefully a writer who knows something about craft, who can read for you consistently? Sometimes a single external sensibility (that is, a person) can help as much as a class. (I know this one contradicts my title.)

3. What really irked you during your workshop/criticism from editor? Not just stupid comments but ones that hit home…"Honesty is the first step in greatness," said Samuel Johnson and one thing that revision is about is honesty. It's worth asking yourself a question you can pay a psychologist to ask you: What am I avoiding? Other questions to ask yourself: Where am I being dishonest? Glib? Taking shortcuts? Where am I inserting an opinion/generalization/idea that I haven't really thought out? Why did I include this? What does it mean to me?

4. Often our own writing is interesting to us because it happened to us. Is it interesting to a stranger? Don't come to your work with an overly critical attitude–"It's all boring"–but do ask yourself why someone else would be compelled to read it. It never hurts to ask: Am I being self-indulgent? (I usually answer yes, and continue on.)

5. Make the verbs active. Unless you have a specific mood in mind, think movement.

6. Is there a reason you aren't turning something into a scene or at least a mini-scene? Is that reason laziness?

7. Use earthy details to deflate pomposity. It's worth remembering that for every glistening lily we see there exists a can of Alpo dog food.

8. Smell, taste, touch, sound. Is your piece taking place in a a sensory vacuum? Overdo it–you can always scale back.

9. To paraphrase Bernard DeVotto, "Revision separates the women from the girls." Remember revising doesn't have the la-la nearly hallucinogenic thrills of some first drafts. It is about work, craftsmanship, thought. But it can be very satisfying in a different way.

December 19, 2011

Audubon Christmas Bird Count 2011-2012

I saw this rainbow bee-eater in Australia, and in my dreams at naptime, but not during the X-mas bird count this year.

This year marks the 112th Audubon Christmas bird count. It was begun in 1900 by my hero Frank M. Chapman to replace the Christmas bird hunt, wherein teams of well-heeled sharpshooters went out on Christmas day to see who could destroy the most birds, which they did in the millions. Even then declining populations of birds had conservationists (if not conservatives) concerned. The bird count caught on, and the deadly version of the hunt ended.

#

Last year, according to the Audubon Society count summary, "All counts combined tallied 61,359,451 birds; 57,542,123 in the United States, 3,355,759 in Canada, and 461,569 in Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Islands species totals were impressive as well. In the United States during the 111th count, the total tally was 646 species, plus an additional 45 field-identifiable forms." These numbers can be used to spot trends, find trouble spots, and highlight good news. The counts aren't meant to be comprehensive, but provide comparative numbers for analysis.

In Farmington, Trevor Persons, a herpetologist by day, is kind enough to organize the count each year. And each year, when I get the email from him, I wonder if I really want to get up for a 7 a.m. meeting at the McDonald's in town. (My first year was the first time I'd ever set foot in the place–it's nice, with clean bathrooms, and food, apparently, mostly made of corn.) But once the blood gets flowing, and once you're in the woods, the count is really quite fun. Trevor divides the volunteers into teams of two, except Bob Kimber, Drew Barton and I, who insist on being inefficient and going out together, the three binoculateers, for a day of conversation, farting, and exploration. And of course counting. Drew was late this year and had to meet us at Titcomb Mountain ski area, so I got to be the secretary, frequently losing Bob's pen, but feeling like a big deal nevertheless, like the kid who gets to beat the erasers in first grade (never I).

December 17, 2011: It's fucking cold and damp as dawn breaks. The birds are smart and wait for the sun, which appears with Drew about 9:30. We humans drive from likely location to likely location, finding what they find and keeping tallies to report to Trevor, who reports in turn to Audubon. Bob and Drew and I spotted the following, not our best year, but not our worst, either. We quit at about 1:00 due to advancing age and the imminence of naptime, so I added my backyard birds to the count. One depressing note: pine siskins, once plentiful around here in winter, have not been seen for some years. I'm a big siskin fan. My personal favorite this year was Red Breasted Nuthatch, for its color in a wan world. Perennial favorite is golden-crowned kinglet. Didn't count many woodpeckers or jays, surprisingly, and no sparrows at all, nor waxwings, nor raptors, nor cardinals, nor rarer types, and no surprises (team Trevor saw a snipe last year) but that doesn't mean these birds weren't out there somewhere, and doesn't mean they weren't out there in great numbers. Though then again it might mean that. In an update, I'll add the rest of the Farmington figures, the Maine figures, and the national and international figures. But for now:

Bob and Bill and Drew's team count (capitalized per convention):

8 Ruffed Grouse

71 Rock Dove

11 Mourning Dove

1 Hairy Woodpecker

1 Downy Woodpecker

1 Pileated Woodpecker

16 Blue Jay

28 American Crow

1 Un-American Crow (according to Newt Gingrich)

3 Red-Breasted Nuthatch

16 White-Breasted Nuthatch

2 Brown Creeper

3 Golden-Crowned Kinglet

8 American Robin

61 European (Socialist) Starlings

1 Junco

5 Purple Finch

45 All-American Goldfinch

18 species

3 sound naps

December 16, 2011

My Wind Journey

Bill gave us his take on wind energy not long ago. Here is mine, published this week on my NRDC blog (yes, I'm double dipping): David Gessner's 'Wild Life'.

Bill gave us his take on wind energy not long ago. Here is mine, published this week on my NRDC blog (yes, I'm double dipping): David Gessner's 'Wild Life'.My Wind Journey

Let's start with love. A good place to start, yes? In this case love of a place and love of a book. The book is Walden by Henry David Thoreau, which I read as a young man, and the place is Cape Cod, or, more specifically, the East Dennis beaches I have been coming to since I was very young. My love of those beaches is, at first, a young man's love, but later it grows into something deeper. Inspired in part by Thoreau's book, I move there after college and work part-time as a carpenter while writing my own first book. Though I have now lived all over the country, it is still the first place I think of when people mention "home." It is my Walden and Cape Cod Bay is my Walden Pond.

So of course when someone — a businessman no less — suggests that he wants to place 130 wind turbines — bird-killing turbines! — in Nantucket Sound off the shores of my Walden, I react with outrage. Not in my backyard? Not in my backyard! This is a sacred place, a place apart, and if this is a sacred place then these wind turbines are, as I tell anyone who will listen, a desecration.

I cling to this position for years, holding tight, but then, gradually, my grip starts to loosen. Some things happen, some things change. The story of those things, those happenings and changes, is the story of my wind journey.

One thing I do is to move away from Cape Cod, and so I start seeing the place I still consider home from a distance, from arm's length, while at the same time seeing how that place connects to others. Another thing I do is start to travel extensively, reporting for an environmental magazine. I visit Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, which seems like driving onto Cape Cod a hundred years ago, until I reach a city called Sydney Mines. The city looks like it has been cracked open and had its insides sucked out, which it turns out, is pretty much what happened. In Mike's Place Pub & Grill, I talk to a local man named Keith who tells me the story of the town's glory years, when it supplied coal for much of Canada, and of the depths to which the town fell after the coal was gone.

"The coal was gone and they had taken everything out of the town. Where it had been wall-to-wall with people on a Saturday night you suddenly couldn't find anyone. Maybe a stray dog and a single taxi. A ghost town."

His eyes drooped as if in sympathy with the town. His voice sounded beautiful, his accent vaguely Irish.

"There were no jobs, you see. Other than funeral directors. There was a big call for those."

The more I travelled, the more I found men like Keith and places like Sydney Mines. Places hollowed out and then deserted. I began to think more, not just about beautiful places, but about what we extract from them. This culminated last summer when I travelled along the Gulf Coast during the height, or depths, of the BP oil spill. There I found the most intense juxtaposition of beauty and energy as I spent mornings birdwatching — seeing roseate spoonbills and ibises — near Halliburton Road and oil refineries, or spent a night out in a fish camp, a few hundred yards from a fringe of marsh that appeared burned, but was, in fact, oiled.

The place was stunningly beautiful, and for the Cajun fishermen I met, like Ryan Lambert, it was their Walden. But it was also slathered in the substance that we all use to power our lives. The Gulf has been called "a national sacrifice zone," and it seemed to have been sacrificed so that the rest of us could keep on living the way we live. I thought to myself: this place is connected to Cape Cod. Not metaphorically, but literally, by its waters.

And I thought, because I could not help but think of it, of energy. Where we get our energy from and how we pay for it, in the broadest sense. As a birdwatcher, I know that every animal is required to do the math of energy in its own way, and humans, whatever we may think, are not exempt. It was Thoreau, our patron saint of frugality, who created the initial ledger sheet, the personal math that many of us have begun to think about again during these difficult times, the calculus of our own input and output. In Walden he did his figuring right there on the page for us. Here is how much I spent and here is what I gained. It is the same math that animals rely on instinctively when they hunt. By Thoreau's reasoning, human lives, like the lives of other animals, require a strict mathematical relationship with energy, its gains and losses, its conservation and squandering.

Years ago, on Cape Cod, I had been quick to embrace, and mimic, Thoreau's love of nature but slow to hear his sterner message of personal responsibility. I rationalized this by saying that I preferred Thoreau the celebrator to Thoreau the preacher. But in the Gulf I found myself returning to the other, stricter Thoreau. His relationship with energy was simple but profound: instead of just focusing on getting more, he limited his input and refined his output.

As I travelled through the Gulf, I also thought back to a meeting I'd had two summers before. A friend had put me in touch with Jim Gordon, the president of Cape Wind, and we met for lunch in Hyannis before driving out to one of the beaches that would face out toward the hundred-plus turbine towers that would make up the wind farm. The beach was crammed with people, umbrellas sprouting and kids running this way and that, and once we got to the shore we looked out past kids on inflatable rafts and roaring Jet Skis and powerboats to where the towers would stand on the horizon. One of the arguments that wind opponents have made is that putting wind turbines out in this water would be like putting them in the Grand Canyon. Jim, consciously or not, was using this beach as both prop and stage, and the message was clear: this ain't the Grand Canyon.

The question many have asked is: does having a wind farm out on the horizon detract from that elemental experience of the beach? The argument that Jim Gordon was making, without saying a word, was that this experience was already limited enough, and that the site of blades blowing in the breeze was not going to detract from it one iota.Now Jim held up his thumb against the horizon.

"From here the turbines will be six or seven miles out. They'll be about as big as my thumbnail."

This, of course, was another big point of contention. How big would they really look from the shore? And what would it mean for Cape Codders to look out at their theoretically wild waters and see what would be, for all its techno grace, an industrial site? While I had deep sympathy with the aesthetic point of view, it was hard to argue that windmills that would appear a few inches tall on the horizon would ruin the place's wildness.

And with what Jim said next, he almost won me over entirely. "We need to connect the dots," he said.

Connect the dots. Wasn't that what Thoreau had tried to do? Wasn't that the definition of ecology?

"We would barely see the turbines from here, but maybe we should see them," he continued. "It's what we can't see that's killing us. Like the particle emissions from the power plant in Sandwich. And the oil being shipped to run that plant."

He shook his head and stared out at the horizon where his windmills would turn. "Maybe it's not such a bad idea for us to see just where our energy is coming from," he said.

I nodded. At the time my thoughts on wind power were still in flux. But with this I could not disagree. I still was, and still am, worried that migrating birds might run into the turbines. A million birds a night migrate over the Cape during the fall migration, and I fret that by supporting wind I am becoming an avian Judas. But it is a time of tough choices.

"Do you know the windfarms will kill more birds in a year than were killed during the whole Gulf disaster?" a wind opponent said to me recently. This "statistic," of course, hinges on a very narrow definition of bird fatalities. My accuser was not thinking of habitat destruction and warming, and the whole host of other consequences of the rabid pursuit of oil. Meanwhile, Jim Gordon's camp claims that the slow-moving and well-lit turbines should prove less of a threat to birds than most tall buildings.

I am not sure of that. What I am sure of is that there are no more Waldens, or, more accurately, if there are Waldens then they are all interconnected. Cape Cod has been called "a place apart." I am writing this from Cape Cod right now, and I understand what the phrase means: the land of this fragile ex-peninsula is very specific to itself, and when you come here, and cross the bridge, you leave other places behind and enter a place like nowhere else.

But I can no longer use this term to describe the Cape. It is not apart from the fragile Louisiana fish camp where I spent the night, oil lapping nearby, and it is not apart from Sydney Mines. Each place in this threatened world, separate but connected, must now make an accounting, keep its own ledger sheet with a cold and honest eye. We hold onto our pristine place by sacrificing other places. I hear that up in Nova Scotia, where I visited Sydney Mines, they are proposing power plants that will take advantage of the massive tides. I hope they do and I support it. I also support Jim Gordon and his wind farm. There is no place apart.

December 13, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: Don't be Stupid

One thing I've noticed about good writers, even the most demotic, even the most seemingly down to earth and simple-hearted, even (god help us), the raving right wingers: they're pretty smart. So that's this week's bad advice for writers: Don't be stupid.

One thing I've noticed about good writers, even the most demotic, even the most seemingly down to earth and simple-hearted, even (god help us), the raving right wingers: they're pretty smart. So that's this week's bad advice for writers: Don't be stupid.

#

For example, don't have the phrase "legs akimbo" in the first paragraph (or any other paragraph) of your short story, as a fellow hoping to work with me in private study recently did. Because if you use the phrase "legs akimbo" in the first paragraph of your submission, I will stop reading.

Don't walk up to me at a conference with my latest book in hand and say (as an earnest conference attendee did last summer): "How much did you pay to have this published?"

And don't follow that up by telling me how much you paid to have your book published: a pretty penny, I know.

Don't think your Amazon ranking is important.

And don't use the Amazon ranking of one of my lesser titles as part of your introduction of me at a reading you are paying me a lot to give: like, I don't know, 1,293,546.

Do know what "remaindered" means, and don't congratulate me on finding one of my books on the "remainders" table out in front of Aphidistra Books in Chicago, a great store.

Don't put a picture of yourself posing with a lion in the packet with your novel.

Don't title that novel "Daze and Confused in the Savannah (Not the One in Georgia)."

Don't take Amazon up on their scan anything in your independent bookstore and then buy it from us online and we'll give you five bucks scam. Five bucks? Seriously? You'd take that to help kill off your local bookstore? What else will you do for five bucks? Because I've got five bucks right here.

Don't ask me at a reading in Wyoming how much I paid Philip Lopate for his incredibly kind blurb on Writing Life Stories.

Don't think that you have to pay for blurbs (except in shame while asking, and gratitude later).

Don't come cocking up to me at the Cape Cod Writers Conference six or seven years ago and say, "Why do you need an agent? You couldn't write it yourself?

Don't send your perfectly good story to the New Yorker and then throw it away and delete the file when their intern rejects it.

Don't come up to me after a heartfelt, exhausting talk on scenemaking that everyone in the room adored and say (while the applause is still ringing), "That was pretty slick."

Don't tell me my book was a good read, and that you enjoyed "reading through it."

Don't tell me you're writing a fictional novel.

Don't call your essay a short story.

Read a book.

Read another one.

Don't submit your novel to me "for publication." I am not a publisher, but a writer.

Don't spend several hundred dollars to take a weekend workshop with me only to leap to your feet halfway through a fairly mild discussion of someone else's work to shout, "Who made you the big fucking expert?" Specifically, don't do this in Austin, Texas, in March of 2006. You know who you are.

Don't think or say that The DaVinci Code is a beautifully written book.

Learn how to use a comma.

Don't believe that the reason your book, story, essay, article, hasn't gotten published is that editors suck. Unless it makes you feel better.

Don't use the term "marketing" in relation to a story you've written and are holding up during the Q and A at a reading I'm doing in Ohio. Don't use the term "marketing" in relation to any story.

Don't ask me how my book is doing. My book is doing fine, thank you. It was good when I finished it, and it's still good now.

Don't send me your manuscript with a note that says, "Dear Mr. Roorbach: Please read this at your earliest convenience. It's my memoirs and I know it's going to be right up your ally. No need to write up your critique. A phone call would be fine. I need to know soon because the deadline for the PEN prize is coming right up around the corner."

Don't say to me, "I read your book," and stop there.

December 11, 2011

Table for Two: an Interview with Maureen Stanton

Today I'm going to meet Maureen Stanton, a native New Englander (or Massachusetts, anyway, good enough, and not her fault) whose first book, Killer Stuff and Tons of Money, was published this past summer by Penguin. It's a work of anthropology as much as it's anything, with a deep look at the psychology, the social dynamics, and the caveman economics of flea market and antiquing culture. The book soars way beyond the multiple TV shows on the subject, which tend to focus on objects more than people, on dollars and cents rather than the mechanics of deals made on folding tables and in barns. And don't forget the Internet. Maureen teaches at Missou, now, the University of Missouri, in Columbia, Missouri, and though this is a virtual meeting that could have taken place anywhere (Paris would have been nice, with its vast and famous flea markets—Les Puces, par example!—or in Georgetown, Maine, where Mo lives in summer, only a couple of hours from here, and Maine practically a flea market on its own), I find myself at Shotgun Pete's BBQ Shack, at 701 Business Loop I-71 W, hardly a romantic address.

Today I'm going to meet Maureen Stanton, a native New Englander (or Massachusetts, anyway, good enough, and not her fault) whose first book, Killer Stuff and Tons of Money, was published this past summer by Penguin. It's a work of anthropology as much as it's anything, with a deep look at the psychology, the social dynamics, and the caveman economics of flea market and antiquing culture. The book soars way beyond the multiple TV shows on the subject, which tend to focus on objects more than people, on dollars and cents rather than the mechanics of deals made on folding tables and in barns. And don't forget the Internet. Maureen teaches at Missou, now, the University of Missouri, in Columbia, Missouri, and though this is a virtual meeting that could have taken place anywhere (Paris would have been nice, with its vast and famous flea markets—Les Puces, par example!—or in Georgetown, Maine, where Mo lives in summer, only a couple of hours from here, and Maine practically a flea market on its own), I find myself at Shotgun Pete's BBQ Shack, at 701 Business Loop I-71 W, hardly a romantic address.

Shotgun Pete's

Or maybe it is. Shotgun Pete's is an actual shack, and it's in the middle of a parking lot, and Mo's waiting there under her characteristic fountain of auburn waves and curls, grinning at one of two picnic tables, two paper plates of ribs in front of her, my gigantic brisket sandwich waiting, also tubs of cole slaw and potato salad and bowls of beans, about a gallon of iced tea and two or three virgin forests worth of napkins. And are those things deep-fried dill pickles? Well, always the pro, I have prepared for this interview by reading Mo's book, but also by not eating meat for forty days and forty nights, and, my-my-my, doesn't that BBQ smell good! Make that great. Pete's a local hero, and I'm not above a little worship. I unfold six or seven napkins, tuck them into the collar of my shirt, and I'm off. Always start with the beans! Mo looks amused, then shocked as I crash into the food. There's not even time for a hello, though it's been some years since she and I have crossed.

MS: Bill?

BR: Mm.

MS: Hello? Bill?

BR: Good.

MS (Carefully separating a rack of ribs, and eating): What'd I tell you.

BR: Mm.

MS: Bill, that's cole slaw. You can't drink it.

BR: Talk about your book?

MS: I'll wait for a question.

(She waits, and waits some more, an abstracted smile on her face. Finally, Pete himself emerges from the shack with a high-pressure garden hose, which he turns on Bill, whose face slowly emerges from the delicious, delicious sauce. Maureen pays no attention, starts on her second rib.)

BR: Now that's service.

Mo with Jake and Elwood at Brimfield

Pete (retreating): We aim to please.

MS: A question?

BR: Okay. Fine. (Pulls out an index card, reads mechanically.) I always liked flea markets, mostly for the poking around, but also for the people. So I loved your book, a really concentrated dose of all the coolest items and big moments and fun people and losers and sharks, kind of like a flea market itself, lots of cool stuff and hidden corners, but also some real thinking. (He becomes more animated, seems to realize where he is, notices Maureen.) It's also beautifully written. Did your immersion in the flea world for this project change you, capture you, or did you always remain an observer and reporter?

MS: I haven't done a lot of immersion journalism outside of this book, but I can't imagine that this process doesn't change the writer in any situation as it seems to always be a process of learning and discovery. (Ted Cononver admits to being changed in Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing, though his transformation was more damaging, I think). I tried to become part of the wallpaper (my role was basically as a laborer), and nobody paid any attention to me taking notes, etc., so I don't think my presence altered the people or their behaviors or the scenes I was recording, but I was changed—captured or captivated—by this subculture. I had a longstanding prior interest in the flea market / junk store realm since it is appealingly situated outside the mainstream and somewhat unconventional, but I never had an interest in writing about it until the opportunity came up way back in 2000 when "Curt Avery" came to Columbus and I attended that auction with him.

BR: I hear quotation marks ar

Mo at the 25th Street Flea Market in NYC

ound that name.

MS: Yes, and we can get to that. Anyway, I realized then that there was a fascinating subculture there, with its own language and knowledge base and behaviors. I hadn't realized that Curt had turned himself into a knowledgeable mid-level antiques dealer. I had only heard he was selling at flea markets, and my preconceived notion of that was that he was selling used junk, sort of down and out type of thing. My original title was "Flea People," but that changed pretty quickly with the first "show" I did with him (chapter one in the book) and I could see the knowledge and expertise he'd acquired, and that he was far from the bottom rung of the hierarchy of second-hand objects (though he'd started there).

BR: Your immersion?

MS: My own transformation from dipping into this world over a period of many years (with some greater intensity in 2004-5 before I got this job in Missouri, and again in 2006-7 when I was on leave for a year) is nothing as serious as Conover's psychological stress as a prison guard (and his less liberal stance on crime, he admits), but the satisfying development of an aesthetic and curatorial knowledge; whereas I used to buy old "funky" junk based on its campy appeal, I now see much more meaning in these objects—their histories, their original utilities, rarity, authenticity. Every object has a narrative (even the crap imported from sweat shops, only those narratives are depressing). Objects became interpretable texts (not to sound too academic)—they tell stories if you know how to read them.

BR: And you learned to read them.

Glove forms, Brimfield, MA

MS: I think because this subculture is so concerned with material objects, that I now look at any object I might purchase with much more consideration, and I like having that impulse or habit now of paying more attention to objects.

BR: Are you ready to quit writing and start paying attention full time?

MS: Ha. Though the experience was definitely as much an apprenticeship as it was immersion and reporting. But the learning curve is so steep that I'm still a neophyte and could never actually earn a living buying and selling antiques. Aside from that knowledge, I think the most valuable change was that being surrounded by historic objects rekindled my long-dormant interest in history, which had been nearly killed entirely by a very bad history teacher in high school (names, dates, wars, lots of men killing each other). Instead, I re-entered the past through objects, which gave me stories of the quotidian history, daily lives of average people, and that lead me to books about history. It's like I'm in sixth grade again and fascinated with a new world that is the old world. I took just one history course in college since one was required. I picked The History of Lizzie Borden. Then, sadly, I tried to avoid any course or really anything earlier than the 20th century, even in literature and film, until this immersion. Now you talk. I'm going to tuck into some baby back ribs.

BR: Right away in Killer Stuff and Tons of Money, you let the reader know that Curt Avery is not the actual name of your subject. You explain that he needs a measure of anonymity in his work, and that you disguised him for that reason. Did the di

Dressed for Brimfield, a massive flea market in Massachusetts.

sguise cause any troubles for you while drafting?

MS: When I realized that I wanted to write a book rather than just an article, I approached Curt Avery to get his permission. From the beginning, he did not want to use his real name. I didn't question it at all during the five following years that I shadowed him. I didn't ask him to reconsider until my editor put pressure on me to get Curt to use his real name. Even so, Curt never changed his mind and I honored that. His reasons are many, but mostly because he's just a private guy, and a modest guy. His main concerns were that he would come off looking full of himself (I assured him that was not a problem), and that his life would change somehow (he's busy and overwhelmed with trying to sell antiques in a recession, dealing with teenage kids, etc). But aside from that, there are other good reasons for him to remain anonymous. One is that antiques dealers need a certain amount of stealth to buy objects they know are valuable but the sellers don't. You won't see the Keno brothers from Antiques Roadshow out buying antiques at a flea market or antiques show because if the Kenos are interested, then the object must be valuable, so the seller might raise the price. The Kenos and other top dealers have pickers and scouts who find things for them. (In a sense, Avery is a picker for dealers higher-up on the ladder, to whom he wholesales a good percentage of his merchandise.) Then there is the phenomenon of theft of antiques stores and dealers' homes, a very real issue. With a constantly shifting inventory, it is difficult to track, catalog, and insure each and every antique. An object might be in the house only a week, or a day, or tucked away for a few months waiting for a specific auction. Theft in the antiques trade is a real problem at shows, but from homes, too. In Curt Avery's small hometown, he told me that three dealers' homes and shops were burglarized one summer.

BR: Did you approach other possible subjects?

MS: I tried to interview several other antiques dealers, but as I went higher up in the hierarchy, people didn't want to talk to me. One guy agreed when I met him, but then changed his mind when I called for the interview a short while later. Selling antiques at the lower to mid-level, or outside of shops or auctions, is a cash economy, and is dependent on relationships. Anonymity is useful under these circumstances.

BR: Avery is so open in your book.

MS: Right, and I think that if he'd used his real name, he would not have been so forthright and willing to tell everything. So while there may have been something sacrificed in not having his real name used, I think much more was gained in the authenticity and candidness of his remarks.

BR: Wouldn't a little fame actually have helped him in his chosen career?

MS: On some level, people might have been willing to buy antiques from him because they can see he is knowledgeable and ethical, so that's a potential advantage, but then again, buying antiques to resell may have become more difficult for him with a certain degree of fame or recognition.

BR: Did you change more than the name?

MS: I did not change his physical appearance, but recorded it as he looked when I started the project in 2003 (the first show I worked with him), and he'd aged and changed enough by the book's release in 2011 that he is not that identifiable. I omitted the name of his hometown or origin, and his current town also.

BR: Were there stories you couldn't tell? Was it hard to make a round character out of him without being able to show his personal life?

MS: Originally, Curt Avery had been very generous with allowing me to tell his own personal story as background, but as I wrote the book, it became clear that some people would recognize him by the objects mentioned, like the Shaker clock-reel yarn winder, which is a one-of-a-kind object. (Antiques publications report these sales and dealers track objects and auction sales to keep up with market values; they know who sold what where and for how much.) Once it became clear that I could not promise complete anonymity, I had to remove some of Avery's backstory, for example more specifics about the dec

Antiques Garage NYC

ade of his twenties when he was not doing so well. Also, he realized, too, that by 2011 when the book was coming out, his kids weren't small anymore and might read things about his past life that he did not want them to find out about just yet, especially as they were entering their own teen years. There were some very funny "sowing wild oats" stories, but also some sad, really tragic things that happened in his life that I had to omit. The material was compelling, but I was okay with losing it because I wasn't writing a biography of Curt Avery. Since the book is meant as the readers' guide into this subculture, I think we get enough of his backstory to give him texture, put him on relief on the page. Quit eating my potato salad

BR: Just looking.

MS: With a fork? More questions.

BR: Okay. How did you connect with Penguin?

MS: I had an agent who tried to sell the proposal for this book a few years before it sold in 2009, but was not successful. I kept writing and researching on faith that it was a good story and that I hadn't seen a book like it. Then in 2009, I met another agent at the Neiman Center Conference on Literary Journalism in Boston and she liked the proposal right away. It's interesting that it was nearly the same proposal, but the only shift was that the recession hit in late 2008 (the proposal sold in spring 2009), so perhaps the zeitgeist had changed such that people were more interested in the second-hand economy. Just a guess. But my agent knew the editor at Penguin who bought the proposal (they had worked together before) and knew that he had a collection of 600 or so refrigerator magnets, so she made that connection.

BR: That's brilliant. And really good advice about finding an editor. Give "em something they care about. Tell us about your career.

MS: I think I've been really fortunate in my career. I mean, things haven't always gone well (there were a ton of problems with this book because the editor left pre-release and a bunch of important stuff didn't happen, blurbs, pre-release reviews, etc.), but at other times, things have gone really well, like Parade Magazine selecting the book as a recommended summer read, seemingly out of the blue. The point I'm trying to make (rather inelegantly) is that you just have to keep writing and keep faith and remember always that the joy is in the act of creating. I tell my graduate students and aspiring writers about an essay that was rejected 33 times ("Laundry"—a draft of which I turned in for your workshop at OSU), then went on to win a contest, and be reprinted in Pushcart, and earn an NEA grant. And Jack London, who was the first American novelist to become a millionaire from his writing, collected 644 rejections before he was in print. (He started submitting stuff when he was a teenager.) Not that it's about the money, but having money can buy you time to write. And it's nice to be paid for your work.

BR: Well, now that you've let the cat out of the bag, let me mention that you were in the graduate program at Ohio State while I was teaching there, and a favorite writer in my nonfiction classes.

MS: MFA programs are regularly criticized for turning out cookie-cutter writers, among other gripes, but the MFA program at OSU was the best thing for me. I had great teachers (this brilliant writer and teacher named Bill Roorbach, with whom I took four workshops and learned something new every time), I had time to write, a community, health insurance, a small but steady paycheck, and most importantly, being in the MFA program allowed me to take myself seriously as a writer for the first time in my life. You don't need an MFA to be a writer, or a successful writer, but for me, it was the gateway to my career.

BR: Bill Roorbach is not my real name, of course. I've changed it to protect myself in this doggy-dog world (as a friend's kid put it) of writing. Let's move on to geography. I don't know if you know, but my parents are from Missouri. They grew up in Liberty, which is now Kansas City. I know Columbia's a bit of a different world. How are you liking it?

MS: I had no idea you had this Midwest background.

BR: I was born in Chicago. Lived there till I was one.

MS: I've battled the Midwest over and over. I was taken to Michigan by a boyfriend and lived there for a decade, returned home to Maine, only to be drawn to Ohio for graduate school. Then back to Maine, only to be drawn to Columbia, Missouri. Quite honesty, this is fantastic job—I couldn't ask for a better position and I feel fortunate to have gotten this job, but I wish there was an ocean of water nearby, rather than an ocean of cornfields.

BR: How are you enjoying teaching? Tell us about the programs at UM Columbia

MS: Missouri has a Ph.D. program with a creative writing focus, so I teach undergraduates, and then M.A. and Ph.D. students. I think the Ph.D. program in creative writing can be a good place for post M.A. and M.F.A. writers to get another four years of time to write, health insurance, mentoring, teaching opportunities, etc. I enjoy teaching graduate students because the discussion level challenges me all the time, but I really enjoy teaching undergraduates here because many are the first in their families to go to college, or they've not been outside of Missouri much and it's really fun to see their minds expanding through the reading assignments and writing and discussions.

BR: How do you get your writing done? Any tricks for making time?

MS: I find teaching to be all consuming, so for me, it works best if I am teaching 100%, then writing 100%. Missouri has been wonderful in allowing me to have a ¾ position, so I teach 3 classes a year, and often I can teach them all in one term. It is also a research institution so they have generous funding for research leaves, or course reductions. That has allowed me to find time to write. I can write a little bit during the terms I'm teaching, but I'm most productive when I have that clear on/off division in my life so I can be entirely invested in writing or vice-versa with teaching. Of course, I also took a 25% pay cut to teach one less course per year, and I would have gladly taken a 50% pay cut to teach two less courses, but then I would not have been eligible for benefits. At this point in my life, I'd much rather have time than money; time is the more rare and valuable currency.

BR: I'll give you three hours for the rest of those ribs.

MS: Dude, never. (She eats.)

BR: How did the structure of Killer Stuff and Tons of Money come about? How would you describe it?

MS: I'd call it more of a horizontal structure, though there is a slight narrative arc. Mostly it's a journey into a strange but familiar world (or your term, if I recall correctly—a tour through exotic territory). In my essays I tended to weave personal story with background/research; I used that same structure in this book, so there is a foreground narrative—the scenes with Curt Avery at shows, auctions, out picking shops, etc. with the arc of seeing if he can rise in the ranks, or wondering if he will find the holy grail of antiques on any given day in some dusty antiques shop. The background narrative dips into the history of the auction, or the psychology of collecting, or the history and phenomenon of fakes and frauds. So the chapters alternate between scene and background. Sometimes this scene/background structure exists within chapters, too, as in the auction chapter, where the live action is interrupted briefly for a bit of background on auction theory.

BR: I love when Avery comes to your house for dinner before a big show (and after you've learned a great deal) and tells you the silver you thought is real is just plate, that the bowl you thought was nothing is late 18th Century Chinese export Imari, and then sets you straight on all your collectibles. It's classic self-deprecation on your part, but it's also a great way to show Avery and his almost casual expertise. Did you have any trouble keeping the tension and the pace in a story that has a pretty single-minded focus?

MS: It was challenging because after a while, the antiques business is the same thing over and over. Trying to hunt for antiques, hauling them around, trying to sell them. I worked so many more shows with Avery than appear in the book and interviewed a bunch of other people who never made it into the book—I immersed myself into this world almost to the point of losing my eye for what was interesting. When I started thinking maybe I'd set up at show or do this in retirement, I knew I'd better get to the desk in a hurry. I had about 900 pages of material, so I really had to whittle down. But that large amount of material allowed me to select the more interesting shows, and to include stories and moments that added some new angle, so that helped to keep the narrative fresh. I think I really I lucked out because I recognized that Curt Avery is a ready-made character, a good story-teller, very quotable, and he has this interesting complexity of being super sharp and erudite while also rough-cut and blunt. His passion bordering on obsession is both admirable and at times worrisome, so added texture to the story.

BR: I love when Avery sells a pot to another dealer and says, "I just made a mistake." His questing character comes out beautifully in these moments. Were you taking notes like crazy, or do you work more from memory? Or tapes?

MS: All three. I carried around those long narrow journalist's notebooks—they fit nicely into your back pocket—and jotted down all my observations at the moment whenever possible. At night in my tent, or sitting in my car, I'd add some context and add things from memory that I hadn't been able to capture during the hectic show. I also brought a tape recorder everywhere so I interviewed Curt Avery in person, and I did a bunch of phone interviews. It was really important to get everything down on paper or computer as soon as possible so I could add impressions and context for the quotes and observations I jotted down.

BR: I love those antique hunter and flea-market shows on Cable TV. The basic narrative is always a great sorting through pedestrian stuff on the way to the discovery of treasure. Or the kindly woman who has no idea the value of that blanket chest. Did you find yourself working within the TV narrative or working against it?

MS: Great question. I was working against that narrative. One newspaper writer asked if my book was a "corrective" to Antiques Roadshow and American Picker, and I think that it is, even as it partakes of the "adventure" or "quest" narrative. I'm not criticizing those shows; they have to be interesting so they must show success, or else nobody would watch them. If Antiques Roadshow tried to show real reality—the 14,000 worthless objects that people carry into a day's taping instead of the 50 historically important, valuable, or odd objects that make it onto the show—then it would be a dull show. But those shows don't or can't give the truth of the long, steep, and costly learning curve a dealer needs to be able to walk into a shop and pluck the thing that is underpriced tenfold, or what it's like to unpack 300 items, sell 20, pack up the remaining 280 in the pouring rain, drive home, and do it again as day or two later, 30 or 40 times a year. Or how your family feels when every bit of space in the house, garage, and basement is taken up with your inventory. Or even just how to tell if any given object of the 35,000 collecting categories is valuable or if it's a worthless fake or a reproduction. Or what it feels like to miss a $1000 profit because you were 10 seconds late into a booth behind another dealer.

BR: You've got a huge bibliography. How did your library and other academic research mesh with your fieldwork?

MS: I over-researched like crazy both due to my fascination with objects and their stories, but also out of a neurotic insecurity that I had no idea what I was talking about. I am not a historian nor have I ever studied history.

BR: Except, of course, for Lizzie Borden.

MS: I am not an antiques dealer and had no knowledge of the antiques trade; and I am not a trained journalist. I was terrified I'd get some important historical fact or some facet of an antique flat wrong. So my policy was to find at least three sources for a fact. Often I had to track down more sources because the historical record is so varying and flawed. So then I tried to find original sources, like estate documents, etc., and if I couldn't find a primary source, I'd refer to the source that was most credible, or use the "majority rules" policy. When three historians or sources said the grasshopper weathervane on top of Faneuil Hall in Boston weighed 38 pound and one said 90, I went with the claims of 38, especially since one of those sources was a highly credible museum curator who wrote a book on the weathervanes of New England. I bought a lot of out-of-print books. But I also grew obsessed with certain objects and just wanted to learn more about them. My editor made me cut about 75% of the research-ey vignettes about objects. The book is definitely more readable because of that, but I hated losing the esoteric information on forks—all four pages of it down to one paragraph.

BR: That's what websites are for! The new footnote…. Did you do the index yourself? What was that like?

MS: No, Penguin did the index. I built an index for a professor at Ohio State when I was a graduate research assistant, and I liked that work; it's like cleaning out a file drawer or closet, and ending up with this beautifully organized and searchable system. I wish I'd done my own because I think it would have been more thorough, but then again, I just didn't have time so I was glad they took care of that.

BR: Have you heard from Avery? What was his reaction to these pages?

MS: I see him on occasion, a couple times a year. I was invited to sign books at a show produced by Marvin Getman in Boston, the setting for the "John Malkovich Show" chapter (Getman was a really good sport about his role in that chapter.) I saw Avery, who was set up to sell at that show. I've emailed him some of the letters I've received from readers, which have all been favorable. (Only one person wrote to complain about Avery's profanity, but even that guy still said he liked the book overall.)

BR: What's with these fucking people who complain about profanity?

MS: Curt's had a few offers via these letters to exchange scut labor of moving boxes and unpacking for the opportunity to learn from him, but he's really a loner, a maverick. He allowed me to shadow him because we were friends, but also he trusted me to tell the story straight, and he really wants everyone (!) to love antiques as he does; he saw the book as a way to educate people. A few people in his sphere in New England have recognized him, and they've kidded him, but they have also respected his continued desire to be anonymous. He doesn't deny that he's Curt Avery if someone asks, but he's not advertising it. I usually work one show a year with him still, the one in Maine that's close to my house.

BR: Did you end up with any stuff from all this work? I mean, is your house full now? Any objects you can't forget?

MS: I really fell in love with hooked rugs, which I'd always liked but never really understood, when I learned that this folk art began as a craft of necessity and ingenuity that became an art form. Hooked rugs originated in Maine, and the earliest ones were done by women using a crude tool like a bent nail, old burlap sacks, and cut up discarded clothing. There's a 19th century story of an 11-year-old girl from Wiscasset, Maine (up the road from my house), who memorialized her mother's death by using her old clothes to hook a rug. It's a little heartbreaking to envision this young girl whose beloved mother passed away, spending hours by candle or oil lamp stitch by painstaking stitch trying to hold onto the memory of her mother and honoring her through this humble rug. I took an all-day rug hooking class and learned how truly difficult it is to hook a rug. (In my typical fashion, I have an ever-unfinished, badly hooked pot-holder-size thing in a bag somewhere waiting for me to someday finish it or die.) I now have several hooked rugs that I've bought at antiques shows and flea markets, and can tell the better ones from crude or machine-hooked rugs.

BR: Any new collections?

MS: I didn't take up collecting anything in particular as a result of researching this book, but I buy antiques or vintage stuff now whenever I can instead of new things. Most of the older stuff is just more unique and interesting to me—it's often cheaper—and it means I'm not participating as much in the economy of buying poorly made, sweatshop crap that is manufactured and shipped from China and other developing nations at great expense to everyone's environment. And it's just fun to look for cool, weird and beautiful things among the heaps of cast-off stuff.

BR: Like the rest of those ribs?

MS: Hands off!

December 10, 2011

Cover Me (Part III)

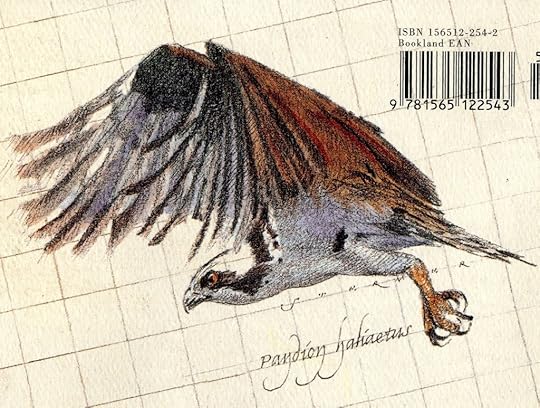

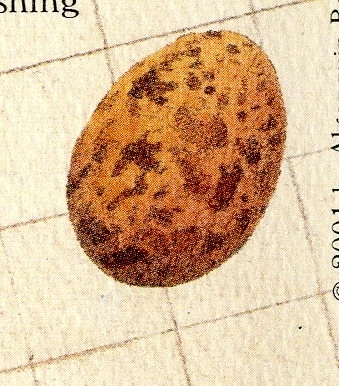

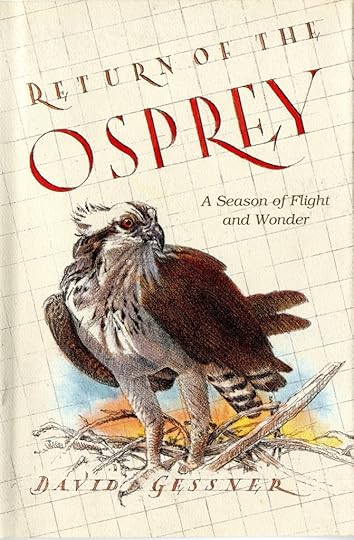

Today's sad and unexpected news combines elements of our last two posts. The news is of the death of Dugald Stermer, who was many things during his varied career, including the editor of the radical 60s magazine, Ramparts. He was also a stunning artist. One of my favorite of his drawings was the cover he did for my book, Return of the Osprey. He also drew a bird in flight for the back, and as an added touch he painted an osprey egg for the back flap. These drawings alone give you a sense of craftsmanship, dedication, and grace he brought to all his work. We need more human beings like Dugald Stermer on this planet. He will be sorely missed.

Today's sad and unexpected news combines elements of our last two posts. The news is of the death of Dugald Stermer, who was many things during his varied career, including the editor of the radical 60s magazine, Ramparts. He was also a stunning artist. One of my favorite of his drawings was the cover he did for my book, Return of the Osprey. He also drew a bird in flight for the back, and as an added touch he painted an osprey egg for the back flap. These drawings alone give you a sense of craftsmanship, dedication, and grace he brought to all his work. We need more human beings like Dugald Stermer on this planet. He will be sorely missed.

Here's a link to today's obituary in The New York Times.