David Gessner's Blog, page 99

November 23, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: Turn the Page

Betsy Lerner (Bill's agent by the way) said this in her terrific book on writing, The Forest for the Trees : "I urge all my writers to get to work on their next project before publication. Working on a new book is the only cure for keeping the evil eye away."

Betsy Lerner (Bill's agent by the way) said this in her terrific book on writing, The Forest for the Trees : "I urge all my writers to get to work on their next project before publication. Working on a new book is the only cure for keeping the evil eye away."

This is sound advice, and it is grounded in the fact that the writer's mind, when stripped of its main obsession—writing—will turn to other darker objects.

So today's advice: turn the page. Which makes great senseYes, it makes sense but, as I learned over the last few months and Bill will learn soon with his novel, but…..as I've learned latley, is a little harder these days. Ideally, I think, all of us writers would swing from book to book like Tarzan from vine to vine. But what sometimes interrupts all the swinging is the necessity of selling the book. Reviews, Amazon, sales, slights, good readings, bad readings, victories, losses. For a while after publication all the focus is on the past book, the done thing, the dead thing.

That's how it's been for me at least. But over the last few days a few green sprigs have grown up through the compost. And yesterday the new words really started coming. Hallelujah! Blessed relief. Suddenly things about the old book fade. The new book grips the mind. There's no time for envy and pettiness or even indolence because you've got a fucking book to write! The excitement builds along with the desire for privacy. For putting up walls. For retiring to the hermit writing cave. In other words it's time to stop posting your status update on Facebook, and start posting it in your journal. Time to start imagining a new world and let the old one shrivel.

This goes for books that you don't publish too.

In his great essay, The "Siphuncle," David Quammen writes: "I spent three years at menial labor while writing a novel about the death of Faulkner, a novel that no one at the time or for years afterward wanted to publish, and by now I don't either. But it took much time and energy to seal that one behind a wall."

I have some experience with leaving behind unpublished books, having written approximately eight books that have not seen the light of day. These were not dashed off drafts, either, but multi-draft projects that each took years, and that, if I do say so myself, should have been published. I could gripe about that, and I certainly have over the years, but the point for today is that those had to be left behind. That is, even after their "failure," I had to turn my imagination away from them and toward the new. It's true that it's harder when publication doesn't provide–dare I utter the clichéd word–closure. But the truth is that it's hard either way. Hard to juice yourself up again, throw yourself in, leave the thing that obsessed you behind. Maybe I don't really have much advice, good or bad, regarding this, other than you have to do it or you will stay stuck forever to the old book and will likely die as a writer. Move or die!

The best cure is excitement. That is what usually helps me get moving. After all, I know I only have a finite number of years and there are so many things to get excited about in this world. What I have lately found myself getting excited about is the West. Having written books about the Charles River and the Gulf, I want to turn to a vaster nature. A while ago I wrote an essay called "Father Wallace, Uncle Ed," about my wrestling with the ghosts of Stegner and Abbey and now it occurs to me that there might be a book in this. What if I spent a month next summer following the footprints of these giants through the West, taking notes for a book that would braid literary biography, travel, and the sort of writing about resources—about oil and fracking and pipelines–that drove my book about the Gulf. As always, factors from my own life feed the excitement of the idea. I remember that Hadley, now eight, has never been west of the Mississippi. I dip into Stegner and Abbey out in my reading shack and remember how much I love their writing. And I think of hiking into canyonlands and my heart beats a little faster.

And then…viola! The page starts to turn. Goodbye Gulf or Mexico, hello Utah! Of course a new project implies a tremendous amount of new work, as well as the negative decision not to work on all the other possible new projects. But so what? I am excited now. The work and words will follow…..

November 22, 2011

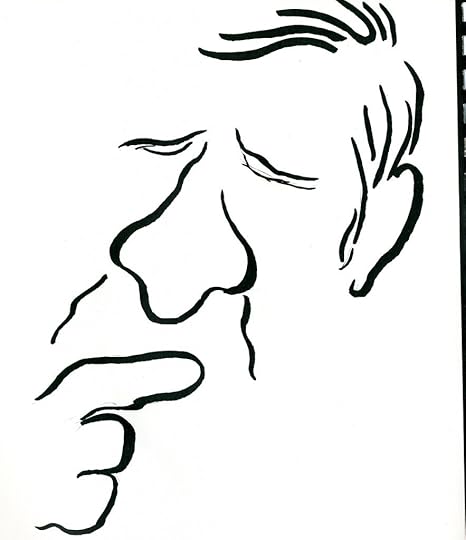

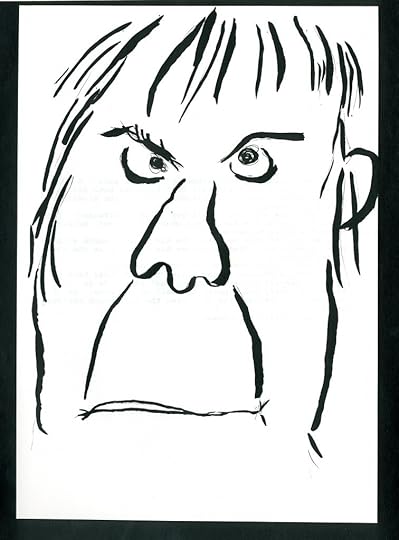

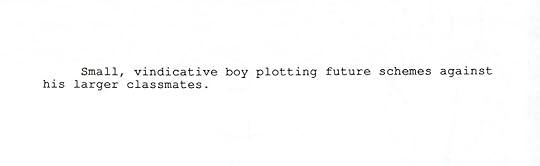

Americature

This is a project that I worked on in my twenties. Like all the other projects from that time, it never saw the light of publication. I'll be excerpting from it from time to time.

To be Continued…..

November 20, 2011

Visual Haiku

wild cucumbers

Herewith, a couple of visual haiku. Three lines invoking a season, denoting a shift or change. Silence.

#

And now, reusing the original image as a line [puffballs, jack-in-the-pulpit seeds, wild cucumbers]:

Americature

This is a project that I worked on in my twenties. Like all the other projects from that time, it never saw the light of publication. I'll be excerpting from it from time to time.

To be Continued…..

Mr. Hopeless Redux

Some of you may recall the post I wrote in June called "Mr. Hopeless," in which I took on Derrick Jensen, and tried to explain why his world view chafed against mine. Well, this comment just appeared on that post and I think it merits being more than just a comment. Here it is:

Some of you may recall the post I wrote in June called "Mr. Hopeless," in which I took on Derrick Jensen, and tried to explain why his world view chafed against mine. Well, this comment just appeared on that post and I think it merits being more than just a comment. Here it is:

98% of the old growth forests are gone. 99% of of the prairies are gone. 80% of the rivers on this planet do not support life anymore. We are out of species, we are out soil, and we are out of time. And what we are being told by most of the environmental movement is that the way to stop all of this is through personal consumer choices. It's time for a real strategy that can win.

Where is your threshold for resistance? To take only one variable out of hundreds: Ninety percent of the large fish in the oceans are already gone. Is it 91 percent? 92? 93? 94? Would you wait till they had killed off 95 percent? 96? 97? 98? 99? How about 100 percent? Would you fight back then?If a foreign power were to do to us and our landbases what the dominant culture does – do their damnedest to turn the planet into a lifeless pile of carcinogenic wastes, and kill, incarcerate, or immiserate those who do not collaborate – we would each and every one of us – at least those of us with the slightest courage, dignity, or sense of self-preservation – fight them to the death, ours or far preferably theirs. But we don't fight. For the most part we don't even resist.

It is time for this to change. Deep Green Resistance is a new, radical environmental movement. Deep Green Resistance is for those who can't wait anymore. For the heartbroken. For those who are tired of ineffective activism. For those who know the real world and are willing to do whatever it takes to protect it and restore it and ourselves. And most importantly, for those who are willing to consider a new strategy. DGR has a plan of action for anyone determined to fight for this planet….and win.

Find out more at:

deepgreenresistance.org

November 19, 2011

Beyond Flipper

Like any sane person, I am fond of dolphins. For the last seven years or so, since I moved south, we have been on neighborly terms. I remember my first New Year's Day in the South, eight years ago, when I kayaked over to Masonboro Island. Escorted by a squad of pelicans, I paddled across the channel thinking of birds and looking to the sky, until, suddenly, something rose out of the water. A dorsal fin. Then three more, close by. I'd like to say that I reacted immediately with sheer delight at the wonder of nature, but that would be a lie. The first moment was one of panic, before slow identification of friend, not foe.

On some levels my life has been an erratic one: hard years of debt, failure, and frustration. But one thing I am proud of is this: I have always made an effort to get to know my non-human neighbors. Dolphins have been particularly good neighbors. Moving to the island town of Wrightsville Beach, outside of Wilmington, North Carolina, was a little like moving to the set of Flipper. It's true the dolphins were less interactive than on the old TV show, rarely crying out to you in their ratcheting chatter, never imploring you to save a distressed swimmer or put out a boat fire, but you got the feeling that it was only a matter of time. I'd never felt as unsettled as I did our first fall in the South. My wife and I had a new baby and a new place, and I had a new job. Those early months after the move were a sweaty nightmare.

But dolphins helped. All through our first fall, I would carry my daughter Hadley down the beach in a little papoose contraption called a Baby Bjorn. We would stop and watch the dolphins as they lifted up into our world before dipping back into theirs. Thinking it was only polite, I started to teach myself all I could about dolphins. Like most people, I knew they used sonar, but what I didn't know could fill a whole world. What I didn't know was that just as a person experiences his or her life mostly through sight, and a dog through rivers of smell, dolphins experience the sea around them acoustically. They do this through a process called echolocation that involves emitting between thirty and eight hundred clicks a minute, sending these sounds bouncing off the world around them and then receiving, and analyzing, what echoes back. In this way dolphins sonically understand both where they are and what is around them. In this way, they place themselves and other objects, the bouncing signals providing complex and ever-changing maps of their underwater world.

Looking back now, I see that learning all I could about my new home was metaphorically akin to echolocation. I felt massively out of place in the South and needed to bounce off everything surrounding me before I could call it home. But to suddenly have dolphins in my backyard! Not long after that first New Year's paddle I paid a visit to Dr. Ann Pabst, a professor and marine scientist at the school where I taught. She articulated my still vague thoughts.

"The fact is that no other large wild animal regularly lives so close to man," she said. "It's like sharing land with a grizzly bear."

***

The latest dolphin news from the Gulf of Mexico is not good. Dead dolphins are being found at four to ten times the normal rate since the spill. No study has yet explained the high mortality rate, and scientists warn us not to jump to conclusions, but …

… but let's put it this way: I have been asked more than once this fall why I harp on old news and keep writing about the Gulf oil spill, despite the fact that it is so clearly "over." Dolphins are one answer to that question. When people tell me it is over, old news, I say, "It may be over for you, but not for the locals." And no one is more local than the Gulf dolphins.

I remember a day during the height of the BP spill, when I was out in a boat with some members of the Cousteau Ocean Futures Society film team. There was a thunderstorm over the marina in Buras, Louisiana, and we were waiting out the storm in Barataria Bay when a pod of dolphins showed up. We watched the dolphins sea-serpent in and out of the water, their bodies sleek, black-gray rubber balls gleaming with water. They cycled up and down as if moving in a circle: a constant rotation from air to water. From up close you could stare right into their intelligent black eyes — no pupils, all black. The best moment was when a mother and her two young glided close to the boat. The mother swam by and the young one followed.

Despair mixed with delight, as it often did during those strange days. Seeing the dolphins reminded one of the Cousteauians of the plight of the dolphins' large cousins, the sperm whales, out in the Gulf. The team had been out on the Gulf trying to film the whales over the previous weeks, but this was not an easy task, given how few were left and how deep they swam.

"They like to hunt and feed along the continental shelf," my new friend said. "They prey on giant squids that live exactly where the oil is. There are only about 1,300 of them left here, so the loss of even one whale is crushing."

It is hard to overcome our anthropocentric bias, to understand that animals have complex lives and that the loss of those lives is not just simple cold fact. But in the midst of considering our own plight, don't we owe it to ourselves to consider theirs? I remember a story that a charter fisherman named Kit told me back on Wrightsville Beach. We were drinking beers at the marina when Kit, a Hemingway look-alike, described watching a dolphin give birth from his boat. The dolphin baby was stillborn, but the mother wouldn't accept the loss. She kept nudging the small dead body up toward the surface with her snout. When the baby got to the surface, it would sink back down. Then the mother would once again push it up toward air.

Here is what I thought that day as the dolphins swam by our boat in the Gulf: these sentient beings, these families, are now swimming through 200 million gallons of oil and millions of gallons of dispersants. A people that rarely have empathy with Homo sapiens from other parts of the world, and that only recently released a substantial percentage of its own population from human slavery, may not be expected to have empathy with Tursiops truncates. So how to stretch our minds, how to understand that this was not just one of the greatest environmental disasters in United States history, but in dolphin history? We will not see the full body count of course, since most dead dolphins, like the stillborn baby that Kit saw, sink to the ocean's floor. Out of sight, out of mind.

That day we watched the dolphins for a while longer, though they seemed to be getting bored with us. They swam, farther away from our boat, but, before they exited, they provided one final treat. A large individual circled back and slapped its tail, a big sharp crack. Then it dove down and swam off. I wondered out loud if the dolphin we saw was "fishwhacking," which consisted of batting fish with their tail flukes, so that the poor stunned fish sometimes flies 30 feet in the air. The truth was that the dolphin might have slapped its tail for any number of reasons, including sheer exhilaration. Who knew? Dolphins are generalists, with no one set fishing behavior, and adapt differently in different places to the local tides, geography, and fish population. In other words, they are creative thinkers, not inclined to doing things just one way.

After a while the storm passed and we headed back to Buras. I stood in front of the boat and held onto the bowline as if surfing, bouncing along, wondering if any dolphin bowriders would join us. I loved the feeling of being out there, of salt and sand and sun, of having spent a day outdoors with dolphins, of living out a childhood fantasy by riding in a Cousteau boat. But the feeling was not a childhood feeling. I knew too much. I couldn't stop thinking about the dolphins. I couldn't stop imagining those smart, interactive, family-oriented animals swimming through an oil-and-chemical pool of slime.

Was there anything good in all the ugliness? I had heard a hundred people say that perhaps the spill would lead to a time of reckoning. That even those of us who would rather not think about these things, would find ourselves thinking: just what have we done?

But these questions faded when the spotlight did. We humans can handle only so much guilt, and we grow weary of the work of empathy. Soon enough the national media skipped on to its next big story.

The problem was that there were many, both dolphin and human, who weren't able to move on. This is where they were from. And they have stayed stuck here in this place they call home. Mired.

It is the locals who often take the hit in service of our global needs. Dolphins are locals here, more local even than the Cajuns and their drowned camps, and they have their own local culture that will be lost along with the human one. From different places spring different dolphin qualities. When I paddled from North to South Carolina a few years ago I stopped at Jeremy Creek in the town of McClellanville, South Carolina. There the local dolphins are famous for self-stranding on the town boat ramp and eating fish out of hands of people. In other words, this is a tradition particular to the place, taught from parents to children. I only bring this up so that we don't fool ourselves into thinking it is "just animals" we are killing. These are beings with cultures and traditions.

When we tally up our ledger sheet of gains and losses, we had better consider this. We are gaining oil, yes. But one of the things we are ripping apart is culture. Just as local fishermen won't be able to show this eroding land to their grandchidlren, so dolphin communities may not be able to continue living in a place they have lived in for centuries if we keep taking wild risks for the last drops of oil. The Deepwater spill might not do them in, but what about the next one? In the past few weeks BP has gotten the offical go ahead from the Department of Interior to resume deep water drilling in the Gulf. When we consider what we are sacrificing at oil's altar, we had better not forget certain mammalian neighbors, neighbors who live in communities, mourn for their dead and unborn, teach their children, and call their friends by name.

My initial reaction to seeing dolphins near my home was an almost aesthetic one, like oohing and ahhing at a particularly pleasing painting. But dolphins are not paintings, and they are not symbols of my attempts to find a home. They are the true locals, and I've come to believe that it's just common courtesy, no more than good manners, to treat them with respect. This is not "environmentalism." It's just looking out for one's neighbors.

This post was adapted in part from my new book, The Tarball Chronicles , and in part from a longer essay on dolphins that originally appeared in the Toad Suck Review

November 15, 2011

Bad Advice Wednesday: Memoir, Don't Do It!

My father and mother

People keep asking. "I've been writing about my parents and I don't see how I can publish." "My daughter has always been sooo sensitive about this stuff—she's going to kill me." "The good news is a contract from Scribner. The bad news is that I just realized my PASTOR is going to read this. I mean, ANYONE can read it." "One of my friends here in [an assisted living facility] has read my book and loved it, but she says no way can I publish it. I'll be shunned [by the community]. She says all the regular affairs are bad enough but the lesbian stuff. Oy."

I guess the best advice about writing about people you love or writing the truth about your life if it's in any way unconventional is: don't do it.

The second best advice is, okay, do it, but don't do it out of anger.

The third best (I'm working my way toward the Bad Advice), well, do it, but make a point of protecting yourself and others.

The forth best: write for people who like you. Anyone who shuns you in assisted living because of what you did fifty and eighty years ago you can do without. Your book, in fact, was just a handy shortcut for getting rid of them!

And the Bad Advice? Well, here it is: Fuck it, it's your life, too, write what you want.

At least in the early going. No one has to see your drafts but you and your trusted friends, or maybe agent and editor. The drafting phase is your chance to write freely with no thought of a hostile audience or an audience that happens to be your mom. Write your story, write it true and complete, and then put it away, never to be seen again till everyone is long dead.

Or, write your story, write it true and complete, and then revise it so as to not cause pain to people who don't deserve pain. Lots of ways to do this. One is to read what you've written as if you were the person you most feared reading it. That'll freeze you up fast. But it may point out that only two or three passages in a whole book are really trouble. What can you do to de-trouble those passages? Some can be altered, fudged. Some can be cut with no real detriment to the whole book. Some can be cut and actually leave an atmosphere of the truth that once was there, useful. Other passages turn out to be, well, the whole heart of the book, and leave such a hole when cut that there's no point. Hey. That's good material! How brave do you want to be?

Disguises are great. That's why people use to write autobiographical novels. Your fat family from Des Moines could be depicted as skinny Roma in Hungary, with all the genders reversed yet the basic storyline of whatever horrors and abuse the same as in your actual life.

In a memoir, you can change names, shift geography, make composite characters. But if you're writing about family, well, it's hard to disguise your mother. Like, "My mother was a very tall, thin, Chinese man from Soo Chow." I mean, your mom's your mom.

And how about writing about your children? Fascinating. Especially those that end up in jail or worse. But how do you do it? You make angels of them, that's how. Everyone will understand. And that one flaw can be slipped in as a compliment of sorts. "Riley was a genius with firearms, the best in his class, and the most tattooed. Even without teeth his smile was winning."

Oh jeez, my son's going to kill me on that one. Sorry Riley.

Often, when newer writers ask me about this, or say, "I'm so worried what my brother will think." I catch a funny whiff of guilt, and hear what they're saying as "I am still not capable of being honest about my role in this troublesome episode and/or relationship I propose to write about." Fine—often in the drafting they see themselves, and sometimes that's when a book gets interesting.

Or when the newer writer says, "I really don't harbor any ill will, it's just a story that must be told." I hear, "I want revenge—this person I propose to write about has won in some way, beaten me out in the game of life, and deep inside I know I'm being petty (or worse) and that makes me even madder, so needing a victim who isn't me, I need your teacherly permission to build me a little predator drone and blast a couple of black jeeps off the sands of the desert of my emotional life."

Predator drones are so expensive, and often kill the wrong person.

One further strategy, not always recommended (note the passive voice—I'm scared here) is to give the draft to the person in question, saying, "This is going to be published." Or more flexibly, "I'm thinking of publishing this." Or more yet: "I need your help with this thing I'm writing." (Hopefully not having to add: "I know we haven't talked for forty years." Though that's interesting, too.) Sometimes—and I've seen this happen—your subject will come back after reading and surprise you: they'll love it, no matter how negative, adore it, feel flattered, seen, understood, cared about, loved. Because the truth is the truth. Sometimes, your subject will come with all those feelings, but also some corrections and a bruise or two to discuss. Sometimes, on the other hand, it's all bruises and a lawsuit will be threatened. Because the truth is relative. Especially among relatives.

Another, more journalistic, approach is to interview your people. Let's say it's your sister. Get her side, and make use of her side in your pages. Just lay the two views out there, let the reader decide. (Or make it seem that's what you're doing. You're the writer, you're in charge of perceptions.) So, after a hot passage, why not something like, "My sister disagrees." And then quote her, even at length, even let her tell the same story over again entirely. The reader will know whom to trust. Let's hope it's you.

People are very complex, made up of 10,000 facets and traits. Characters are simple (especially in Shakespeare), made of 100 facets at most, though even two or three can work. You can pick your way through the 10,000 facets of a real person and deliver the truth in a character made of the 100 facets that do the job you need to do without doing the job you don't need to do. That's been my strategy. Make a fond portrait. Use some humor. Don't shrink from the story, but find the most loving path through. Show the clothes folded neatly in the drawer, not the dirty laundry. Same garments, same message, just a fresher path, and rainwater soft.

And listen, if someone awful isn't really important to the story, leave 'em out. An example, just making it up from vague memory, a memoir about a family business: "My brother Jim, a stupid, lying drug addict, never had anything to do with the restaurant."

Then again, if your grandfather was a sexual predator and evil and accounts for your story, you've got the truth on your side. He didn't protect you, no need to protect him.

Of course it's not all family. You might want to write about your doctor, your priest, your catty baseball buddies, your drunken knitting circle. In all cases, the reaction of your people is pretty much a moot point until you publish (which is to say, make public—so many ways to do this now). So don't let worries about the future dispensation of the work shut you down on the writing end. If it's worth writing, it's worth writing for your eyes only. If it's going to be for others, well, all in good time. Even small adjustments can make all the difference. And when the time actually comes, you'll get a legal reading from your publisher. Let them tell you what to leave out. And use your own lawyer, too. Take out insurance. Don't publish in England. And above all, don't listen to me.

Finally I guess, the truth is your best protection. Write what you know and can prove, write what you recall when there isn't proof to the best of your recollection, and do what you can to check up on yourself. Carefully write from your point of view, and be sure to write about yourself and your reactions and your flaws, not only about others. Refrain from judgment. Just tell the stories, make them true, and leave the rest to the reader.

I don't have a son, by the way.

The Top 10 Sexiest Nature Writers in History

(Note: Bill and I felt it was only right to exclude ourselves from this competition. )

IN REVERSE ORDER…….

NUMBER 10: JOHN MUIR

[image error]

It wasn't all mountains and trees at Yosemite.

(Here's the link to where this photo orginally appeared.)

NUMBER 9: RACHEL CARSON

The "come hither" look that sold a million books (and helped outlaw DDT).

NUMBER 8: HENRY "BIG DADDY" THOREAU

Just because he never had sex doesn't mean he wasn't sexy.

NUMBER 7: WILLIAM LEAST HEAT MOON

Some call him "Most Heat" Moon.

NUMBER 6: VIRGIL

The original beefcake.

NUMBER 5: ALDO LEOPOLD

Everyone knows about his land ethic, but few have heard of his secret "sex ethic."

NUMBER 4: ED ABBEY

Number 1 on our list of horniest nature writers.

NUMBER 3: TERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS

Saving the West, and lookin' good doing it.

NUMBER 2: GARY SYNDER

"Hey, Baby, want to come back to my Tepee?"

AND NUMBER 1, WHO ELSE BUT ANNIE DILLARD?

The famous cover shot

Thanks, Dave

November 13, 2011

Big Wind

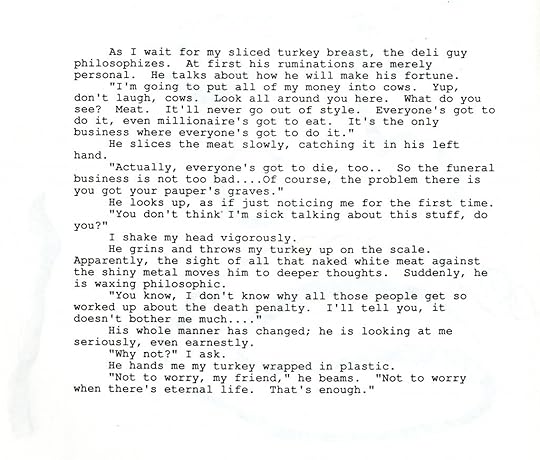

Some of the Towers on Kibby Ridge

I'm writing this column and you're reading it on a computer powered by coal smoldering somewhere. There may be some diesel fuel thrown in, and some waterpower, and no doubt a little biomass, a spot of nuclear, a few turns of wind. But it's only been ten years or so that my writing required any power at all beyond breakfast—I went from a Hermes portable typer straight to an old MS-DOS PC by Zenith, enormous learning curve, hours of study, all those arcane pathways, nothing I need to know anymore, six generations of computers later.

Anyway, if I turn the room lights out while I work tonight, maybe I can conserve enough to make up for the additional usage—I mean the computer screen and keyboard are both lit, after all, and all my attention is upon them, so why do I need any other light? And I could go ahead and turn off the lights in the bathroom, turn off the printer and scanner and copier and fax until I'm ready to use them. I could unplug the TV and VCR and DVD and phone machine and various chargers (toothbrush, cell phone, Makita driver-drill) and even the newfangled beeping toaster when they're not in use—like right now—snuff those little red and orange and green lights that say the machinery is always warmed up. Same with the other dozen little lights all around the house, little lights uncommon back when carbon paper was the only backup I knew, not so long ago. And these dark, late fall mornings—sometimes I've got ten lightbulbs burning by the time the sun comes over the treetops, lights that sometimes stay on forgotten in daylight till noon, long after their battle against seasonal affect disorder is over for the day.

Here's the question: how vigilant would I have to be to save four percent of my electricity usage? Not very, right? Only four percent? Like nothing I'd even notice. Finish a shower four percent sooner, for example. Turn the water heater down four percent, from 110 degrees to 105.6. Move the wheel in the fridge from 4 to 3.5, and so forth, all around the house.

Four percent is how much the Kibby Mountain and Kibby Ridge wind project, approved January 14, 2008, by the Maine Land Use Regulation Commission, might eventually be able to add to the power picture in Maine (pretending for the moment that power made in Maine could be said to stay in Maine).

So here's the next question: should we here in Maine be trading 13 miles of admittedly cut-over (but otherwise undeveloped) mountainside and ridgeline for a four percent we could conserve with no such loss?

Well, the answer's been given, the project approved, and TransCanada has built 44 towers, each 300 feet tall, millions of dollars investment each, all springing up along with new roads and the heavy transmission lines required, a lot of activity and infrastructure in a place that could have fairly quickly crossed back over to the wild side.

Four percent.

#

Bob Kimber, whom many of my readers will know—writer, adventurer, activist, teacher—invited Drew Barton and me for a walk up Kibby Mountain in June of 2007. Many of you will know Drew, too—he's a forest ecologist and a professor at the University of Maine at Farmington and working on a book about the Maine woods. Two fine hikers, endless forest knowledge between them. The point of the walk was to see the proposed site of the Maine Wind Development project. Bob said to bring snow shoes, and we did, loading them into the back of my car obediently, not that any of us had seen any snow in over a month.

Bob has close ties to the Kibby area, having grown up summers and hunting seasons at his father's camps in Eustis, 40 or so miles north of Farmington. Franklin is a big county, and touches Canada. Kibby, in fact, is part of the Boundary Range, international border, beyond which the land flattens into the St. Lawrence Valley: suddenly, people speak French and eat good food.

The three of us talked in English about wind power for much of the hour's drive up there. Bob was way against the proposal. I was inclined to be sympathetic to it, as wind has always seemed like the cleanest possible replacement for fossil fuel power, widely available, cheap, eternal. Plus, the Natural Resources Council of Maine is way for it and gives a lot of information here. I love the machinery, too, fun to see the titanic blades of the windmills coming through Farmington in oversize-vehicle convoys. I always liked the looks of giant wind turbines where I've seen them: the failed elliptical blade on Martha's Vineyard; the failed three-blade monster on Cuttyhunk Island in Vineyard Sound; the enormous windfarm near Joshua Tree National Monument outside Palm Springs, California, thousands of towers like a bumper crop of titanic whirlygigs. In Costa Rica the turbines rose above cloud forest on the verges of volcanoes, picturesque, to my mind, especially in a country where wind provides some 75% of electric needs (and I do mean needs, whereas much of U.S. use is wants). All across the Permian Basin in Texas, too, where the oil used to be: wind towers on every ridge now, and more and more going in, and roads to service them, and power lines to bring the power to market, all in a landscape pounded by cattle and oilmen and perennial drought (and no doubt soon the failure of its aquifer).

Transmission lines. I hadn't thought about. The rights of way for those things are wide and range far. They are traditionally kept clear of foliage with herbicide dropped from airplanes.

Proliferation. Once you open an area to industrial use, it's hard to argue against further use.

Future junk. Simple truths: technologies obsolesce. That's a law of the laboratory. The hulk of the Cuttyhunk turbine is still there twenty years out, having never produced any power, and too expensive to fix. It looks nice on the island skyline among houses, but it's garbage. Who's going to remove all the infrastructure when it's no longer making good?

Big wind. Wind power on this scale isn't an attractive alternative enterprise anymore, but the turf of energy companies whose nature and need is growth, then more growth.

By the end of the ride, I'd modified my thinking: there's more to the impact on remote sites than just the prettily whirling towers.

But still. I'm a big fan. Of big fans. Wind power is terrific when the turbines are sited in areas already thoroughly in use. Wind maps for Maine show all the possible places for the big turbines to work efficiently—not many in southern Maine (except offshore), isolated spots in central Maine, and of course a great many sites in the mountains. Great, I'd say, no problem, put up towers, catch that wind, but do it atop, say, Streaked Mountain in the South Paris area, which is already covered with communications towers. Or on the top of any ski mountain, like already thoroughly exploited Sugarloaf, where a few turbines could power the whole operation: run the lifts, blow the snow, cook the Bag Burgers, light the trails, have some left over for the grid.

Of course, Kibby could be said to be thoroughly exploited already—it's been the site of heavy logging for generations, and really, there's nothing there. Why not towers?

Well, because then there will no longer be nothing there.

#

But this is the story of a hike.

We drove to Eustis, then entered the forest on heavily traveled logging roads, scaring up a small flock of crossbills picking up something in the roadway, finally parking at a trail head, the old fire-warden's trail. Not a spot of snow in sight. So we left the snow shoes. The trail follows a long upward-climbing ridge, and within a mile we were walking on well-packed snow. Soon, the snow got softer, the puddles deeper, the trail, having collected a winter's worth of drift, turning into a pond.

Halfway up, the old warden took a sudden right turn, and the trail climbs more sharply. The snow got deeper and then deeper yet. Drew and Bob are lighter than I, and could walk on top of the pack, only occasionally breaking through. I broke through every fourth step, my shoes getting wetter and wetter, heavier and heavier. This was good exercise, tough on the knees.

Around us the trees grew stunted until we were walking among true Krumholtz specimens, weather-stunted and basically bonsai-ed spruces leaning the way the wind has blown for millennia. Boreal chickadees followed our progress, smaller than the familiar black-capped, and with pretty chestnut hoods, buncha cousins. Blackpoll warblers sang, and yellow rumped, and another warbler unfamiliar, unseen. We hoped to see spruce grouse, but instead got a ruffed grouse so tame he didn't bother flying away, though we walked around and around his tree, marveling: here was a bird who'd never seen a person before.

The last couple of hundred yards were the hardest work, deep, soft snow with a brook of melt running beneath it such that when you went through (nearly every step for me), your feet got soaked in water barely above freezing.

Finally the top. Long views in all directions, crisp, dry day. Mountains and ridges and hills and valleys and more mountains and ridges and hills and valleys. We sat on rocks amongst the boards of the old lookout tower, nothing but a platform now, well dated and initialed. Plenty of smashed bottles. Kids and their fun. But I took off my shoes anyway, warmed my feet in the sun, let them dry, pulled on a fresh pair of socks, ahh, balanced my hiking shoes on blueberry bushes to drain, to take the dry air of the afternoon, to bake in the sun.

After lunch we climbed the lookout platform. Up there, nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing everywhere you looked, the only sign of people a stretch of logging road visible below, and a dozen or so cuttings on a dozen or so hillsides, various ages and acreages, bare swaths, mangy swaths, thick green swaths, light green swaths, the changing forestry philosophies and practices and laws of the decades. Over there, just over the next several peaks and ridges: Canada.

Bob pointed out Kibby Ridge, just across a sharp valley, a little below us. Already there were test towers in place, measuring wind, one, two, three. These must have been dropped by helicopter, no roads in as yet. I tried to imagine 44 turbines whirling, whistling, whisking their four percent for Maine into transmission lines straddling cleared rights-of-way and snaking off into the distance, years of labor, decades of maintenance, some pretty good jobs, for sure, seven or eight of them, probably the company of more wind projects in years to come, now that hearts have been broken (if I may make an analogy from the card game), eventual desuetude, ineluctable obsolescence.

Clean power, though,

#

I haven't been back up there. More towers are proposed. But I guess they will end up as ephemeral as our presence (all of humanity and all of our history, I mean) will turn out to have been.

November 11, 2011

Why Thoreau Wouldn't Drive a Prius

I guess what I'm about to do qualifies as cross-blogging. The below originally appeared in Wild Life, my blog at the Natural Resources Defense Council, and then got picked up by Andrew Sullivan at the Daily Beast and the Wall Street Journal. Now, more impressively, it has been picked up by Bill and Dave's Cocktail Hour.

WHY THOREAU WOULDN'T DRIVE A PRIUS

The short answer: he couldn't afford it.

The long answer: he wouldn't afford it.

Let me explain:

Last weekend I spoke at the house where Thoreau was born, a talk sponsored by the Thoreau Farm Trust. I got out to Concord early and took a walk around Walden. The place was crowded on a fall Sunday, and what was once a one-man show was now a crowd of more than a hundred. The last time I had visited, during summer, SUVs crammed the parking lot and an ice cream truck played its seductive tinkling song.

Last weekend I spoke at the house where Thoreau was born, a talk sponsored by the Thoreau Farm Trust. I got out to Concord early and took a walk around Walden. The place was crowded on a fall Sunday, and what was once a one-man show was now a crowd of more than a hundred. The last time I had visited, during summer, SUVs crammed the parking lot and an ice cream truck played its seductive tinkling song.

During the warm months, the beach at Walden is usually jammed, chairs and umbrellas and floats and life guards and families yelling at each other: People yak into cell phones and boats putter about with the words "Walden Patrol" on their bows. Large sections of the pond are fenced off, and when you walk along the shore you are herded through paths as crowded as airport escalators. Irony is always thick at the modern Walden, and to get to the site of Henry David Thoreau's cabin, you often have to barge and dart and slide past the hordes that clutter the trails, the place having become a Disney recreation of its former self.

But yesterday was slightly less crowded than my summer visit, and if you ignored the fences you could almost imagine the pond as Thoreau had known it. The leaves glistened and the air was cold, and I passed a cove where the water shone a deep blue-green. The cabin site was marked with a great pile of rocks, a cairn, and a sign that informed me, among other things, of the fate of the cabin after it was removed from the site: "At first, it was used to store grain. Then it was dismantled for scrap lumber and the roof was put on a pig pen." That sounded about right. The house itself was a single room, 10-by-15 feet, a kind of anti-trophy house.

As I walked, I thought about how Thoreau's experiment of living by the pond, and in particular Thoreau's personal math, is more relevant than ever. Everywhere you look these days people are singing the praises of restraint and bemoaning the failings of sheer excess. Frugality, that unfashionable virtue, is suddenly back in fashion. How do we make our own home economics, our personal ledger sheet, balance with what is happening in the larger world? Although Thoreau did his share of finger-wagging, it isn't his moralizing that interests me. What is truly exciting is what you might call his celebration of the joys of restraint, his thrill in self-abnegation, as long as it is self-abnegation for a purpose. Perhaps most vital for our moment is his deep-seated and deeply-lived belief, that one can live a good life, and an interesting and compelling life, by consciously doing with less instead of striving, incessantly, for more.

His larger question was "how to live?" and his answer came down to this: since it takes great effort and energy to get the money to get the time to live as one wants — that is, in his case, to walk four hours a day, immerse oneself in nature, and find time to write — why not cut out the middle man? Why not attempt to set directly about doing what one wants to do?

But what about money and getting more? Well, what if instead of needing more, one has a talent for and takes pleasure in needing less? The thrill of this equation for Thoreau, and the challenge for so many of us that have followed, is that he, unlike the rest of us, seemed temperamentally suited to this reductive math. One day he might have three acorns for lunch and, rather than feeling deprived, Henry, thrilled by the momentum of austerity, would the next day cut that number down to two, and then, what the hell, have just one the next. Though he liked being extra-vagant in his language, piling on the sentences, that was just about the only place he indulged in the excessive.

What would his reaction be to the recent news that growth has slowed? Hooray! It's about time! Now we finally have to face reality and can no longer ride along on the illusive wave of eternal growth. And we don't have to be grim about it, either. Our new ambition can be to see how much we can do with little — in other words, we have the chance to refine our ambitions. For Thoreau, as for a fanatic accountant, life was a giant ledger sheet. Of course it was many other things, too, including an arena for heroism and a place of beauty and wildness, but the ledger sheet was never far from his mind. What comes in, what goes out … What do we give up? What do we gain?

Which brings me back to the Prius. It's true that Thoreau, loving the wild world as he did, would choose a car (assuming, for the sake of argument, that he would buy a car at all, an admittedly suspect assumption) that damaged the world as little as possible. But one thing that Thoreau the transcendent accountant abhorred more than anything else was debt. He wrote famously:

How many a poor immortal soul have I met well-nigh crushed and smothered under its load, creeping down the road of life, pushing before it a barn seventy-five feet by forty, its Augean stables never cleansed, and one hundred acres of land, tillage, mowing, pasture, and woodlot! The portionless, who struggle with no such unnecessary inherited encumbrances, find it labor enough to subdue and cultivate a few cubic feet of flesh.

A barn, a mortgage, a car are all things we push before us as we creep down that road. And a Prius, by my estimate, costs about $400 a month, an amount that Thoreau would not just balk at, but probably laugh at. Much preferable would be a car that was far cheaper and still got good mileage, a car that would not require the monthly pushing of a barn, even a barn with wheels. After all, part of the pleasure of the car for Thoreau, even while working as a handyman, would be to see just how little he could use it. That would be fun! And better yet he would buy a used car. You see, he really liked re-using things. (He would have loved that his cabin later lived on as a grain storage bin and then again as a pig pen.) Why not take someone's old car and make it his new one?

Personal addendum: I will end by admitting that the above was, among other things, a rationalization. When I was reporting in the Gulf during the oil spill, I got around in an old RAV4, a car that didn't get particularly great gas mileage. Though I believe that we are all environmental hypocrites in this day and age, I was stung by my own hypocrisy, guzzling gas as I criticized BP. I vowed that when I got home I would buy a Prius, putting an end to my hypocrisy. I put that decision off for a while because we could not afford a new car right away. We finally put the RAV out to pasture and lived with one car for a while, which was a good solution until the school term started and one car no longer worked. So I was now ready to buy my Prius and found myself facing … $400 a month. I do not keep as strict a ledger as my friend Henry, but I knew I was not ready to accept that level of debt. Suffice it to say that the used Scion that now sits in our driveway gets pretty good mileage.