David Gessner's Blog, page 18

May 5, 2015

First Sight

Since I am heading back to Colorado today it seems the right time to post this tidbit from the second chapter of All the Wild That Remains, “First Sight”:

First Sight

The land buckles and rises.

For a thousand miles it rolls out, sometimes up and down and sometimes flat like a carpet, all the way from the old crumbling eastern mountains. But then comes a kink in the carpet. A big kink. The continent lifts itself up, its back rising, and most homo sapiens who are seeing that lift for the first or second or even the fifty-third time feel a corresponding lift in their chests. A feeling of possibility, of risk, of excitement.

That was what I felt, at least, as the West announced itself. What had been a sometimes imperceptible rise for the last few hundred miles suddenly became an undeniable one. The continent convulsed and lifted, mountains thrusting into the sky.

It is an inherently American moment. The same moment that trappers and early pioneers wrote about in their diaries. That mystical moment when East becomes West. The place where the country finally gets bored with itself and reaches for the sky.

Here is the eighteen-year-old Ed Abbey’s reaction upon first seeing the sight he had dreamed of: “There on the western horizon, under a hot, clear sky, sixty miles away, crowned with snow (in July), was a magical vision, a legend come true: the front range of the Rocky Mountains. An impossible beauty, like a boy’s first sight of an undressed girl, the image of those mountains struck a fundamental chord in my imagination that has sounded ever since.”

My first sight came at about 130 miles out. A hazy blue outline like a whale half submerged. I would hate to argue with Abbey, but the mountains I was seeing were not really the front range, or at least not the front line of the front range, but the mountains behind them, mountains that, as I got closer, would be foreshortened out of sight by the view of those in front. These farther mountains loomed, bald for the most part after the weak winter but a few tiger-striped with snow. For someone coming toward them from the plains they stood as a clear statement of change, serving notice you were entering a different realm. They shimmered like a mirage but they were not a mirage. Ledge after ledge, ridge after ridge.

I rolled down the window and it was cool. A godshaft of dying light slanted down, coming from behind Longs Peak. The weather had broken, but all summer the mountains had been on fire, and those fires, the most destructive in the state’s history, had scarred the hills both to the north and south of Denver. In June the mountains had been hidden behind a veil of smoke. And yet there they were, and, despite the fires, despite the drought, despite myself, I was feeling that old feeling and getting excited.

Most of us who were born in the East have stories about our first time seeing the western mountains. My initial sighting came when I drove out here after college with two good friends, and from the far back of a Toyota Tercel, where I had been banished after falling asleep behind the wheel back in Alabama, felt my jaw drop upon seeing the hazy, trippy mountains of New Mexico. The next time I visited the interior West I came from San Francisco and the next on a train trip from Massachusetts to Denver where I pulled in at night. It was the fourth trip, my third from east to west, that stands out and retains something of personal myth. I was thirty years old and had spent the previous year back in my depressed and depressing hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts. I was there because my girlfriend of seven years had, with my urging, chosen to attend medical school in Worcester, and I’d thought myself mentally strong enough to withstand a return to that dying place. I was wrong. The first few months I sunk into a morass of depression and unemployment, and that was before I found out I had testicular cancer. My operation occurred the week of my thirtieth birthday, followed by a month of radiation treatment, which sapped me of energy and hope. But it was in the midst of radiation that I was delivered from Worcester through a kind of deus ex machina. The December before I’d applied to graduate schools, but in keeping with the overall failure of that year I had been rejected by all of them. All except one. That one was in Boulder, Colorado, and by the next August, recovering now from radiation and growing stronger, I found myself heading there.

Declared clean from cancer, I was so excited that I drove across the country in little more than two days. My car, a Buick Electra, was overdue for inspection but it seemed to make no sense to register it in Massachusetts when I would soon be living in a whole new state. The unregistered car leant a western outlaw element to the trip, as did the fact that that each day, after my coffee buzz wore off, I turned to sipping beer. I drove through almost the entire second night in that manner, grabbing a hotel for a few hours near the Colorado line. Seeing the Rockies the next morning at dawn–the peaks white and full and completely unexpected–was one of the most elevated moments I have ever experienced. It hit me with a jolt: my new life! Had John Denver himself come on the radio I would have started weeping and whatever did come on I assure you I warbled along. I felt real joy then, and hope. It was a feeling of coming back from the dead, a feeling of renewal, and it is a feeling that I will forever associate with going west.

April 30, 2015

Table for Two: Debora Black Interviews Abigail Thomas

![Abigal Thomas [photo by Jennifer Waddell]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1430410796i/14710874._SY540_.jpg)

Abigal Thomas [photo by Jennifer Waddell]

Debora: Congratulations, Abby, on the release of your new memoir, What Comes Next and How to Like It . I’m delighted to be able to speak with you about this meaningful book and your writing life. Your writing is truly impressive—precise and perceptive. It often surprised me, the particular way you shined the light. For example, in the final chapter, reflecting back over the events in your book, you write:Love can accommodate all sorts of misshapen objects: a door held open for a city dog who runs into the woods; fences down; some role you didn’t ask for, didn’t want. Love allows for betrayal and loss and dread. Love is roomy. Love can change its shape, be known by different names. Love is elastic.

And the dog comes back.

This is the best definition of love I’ve ever heard. It’s beautiful. Poignant (for the person who has read your book), except that it’s stronger than that, in control of itself. And then so practical and funny at the end, this dog love. All I could do was close the book, and hold it to my chest while all of the emotions and thoughts flooded through. The total of which has me wondering this: When you write, do you sense the quiet power of what you’re writing? Is it something that forms on its own from an unconscious space or do you construct it purposefully?

Abby: First, thank you for saying such extremely nice things. It’s not really a conscious choice, the way I write, except when I revise to make it succinct. I love what you said about its forming on its own from an unconscious space. That describes exactly what writing is like.

Debora: Your last memoir, A Three Dog Life, was about the injury and death of your husband. This new book takes us through the region of what remains—friends, family, pets, home, and new unknowns. You tell us about Chuck, your best friend. You tell us about his secret affair with your daughter Catherine, to whom you had been very close. It’s a monumental betrayal, which hurts you deeply. Yet, it will be Chuck who encourages you to write this book. Why did he believe it was so necessary?

Abby: Good question to which I have no good answer. I honestly don’t know, except he knew it would give me something to do. And we had come through a hard time with a deeper friendship.

Debora: How are the people in your life responding to your memoir?

Abby: They seem to be very happy with it. Catherine read it in various stages and I’m pretty sure she loves it. Ditto the rest of my family. One of my sisters seemed disapproving, although that may be my imagination. And oh well.

Debora: You live in Woodstock, New York. You paint on glass. You write. We learn of the major events that have shaped and re-shaped your life. But then there is the every day. What does a typical day look like for a writer of your stature living in Woodstock? How do you like to flow with your writing work—are you disciplined and in a routine or loose and without rules? Are you interrupted a lot or is a day all yours to invent?

Abby: I’m undisciplined until I am on to something. I can spend days just sitting in my chair, hanging out with dogs, talking to family on the phone, napping. The only disciplined part of the week is teaching (although you can’t really teach writing) the two workshops I give. Thursdays I do a memoir workshop at the cancer support center in Kingston, that is very important to me. As for my own writing, once something has grabbed me I’m sticky with story, writing all the time even when I’m not writing. You know how it is. The best high in the world. As for “a writer of my stature”—well, I just feel like a slightly overweight woman who drinks too much and not just coffee. But thanks.

Debora: You wrote these superb lines:

I used to feel about king-sized beds the way I do about Hummers and private jets and granite countertops, but over the past several years I gained three dogs and thirty pounds, and my old bed, a humble queen, just didn’t cut it anymore. It was either lose the weight, lose the dogs, or buy something bigger.

Is there any amount of forgiveness for the Hummers, private jets, or granite countertops?

Abby: Um, no.

Debora: What has been your experience with bringing your books out into the world? This whole notion of reviews…I mean after so much investment of your work life and then getting through to publication. How much is riding on these reviews in terms of the book’s success—or your own feeling of success? I noticed the favorable review of What Comes Next and How to Like It in the LA Times, by the way.

Abby: Well, once it’s out there you take what comes. I’ve had some miraculously good reviews. The only bad one was the NY Times Book Review, but that one was so nasty I had to wonder if I’d slept with her husband. It actually made me laugh out loud. A good review in the Times would have helped sales, but a bad one, well you just shakes your old gray head. It’s part of the territory.

Debora: You would make a good playwright—you write such strong, compact scenes. They’re really lean in the way that they include only two or three people on one point and how they have this nice, start to finish drama. Plus those brief scenes of exposition would make great monologues on stage. Have you ever contemplated writing a play?

Abby: No, but now I will.

Debora: Is there a next project that you are working on?

Abby: Not yet. I don’t seem to be able to write fiction anymore, and since most memoir is prompted by loss, I don’t want any more material. I do want to write about the pleasures of getting old, all the crap left in the road behind you. A friend asked me how my day had gone a week or so ago. I found myself saying, “Chuck and I ate pancakes at Shindig and then we went to CVS to pick up our prescriptions.” Then I laughed out loud. Ah, the new intimacy. It had been a very nice day.

April 29, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Don’t Read Your Reviews

Many writers have claimed they don’t, Papa H. included. But I don’t have the discipline to resist myself. And hey, if I did I wouldn’t have gotten to read this one by Nick Romeo in the Christian Science Monitor, which chose All the Wild That Remains as their top book in April:

Many writers have claimed they don’t, Papa H. included. But I don’t have the discipline to resist myself. And hey, if I did I wouldn’t have gotten to read this one by Nick Romeo in the Christian Science Monitor, which chose All the Wild That Remains as their top book in April:

“The massive droughts and forest fires that have scorched large swaths of the American West over the past decade would not have surprised Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner, two of the region’s greatest 20th-century authors. Stegner was prophetic in articulating the defining scarcity of the environment west of the hundredth meridian: “The primary unity of the West is the shortage of water,” he wrote. Abbey, meanwhile, blamed the greed of those settling the West rather than the landscape itself; he saw in developers a blind pursuit of growth that resembled the “ideology of the cancer cell.”

These two men are the contrasting heroes of a profoundly relevant and readable new book by David Gessner: All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. In this artful combination of nature writing, biography, literary criticism, and cultural history, Gessner studies two fascinating characters who fought through prose and politics to defend the fragile ecologies and transcendent beauties of the West.

The book is structured as a road trip, and Gessner notes the irony of guzzling gas to retrace the lives and works of two preservationists. But the contradiction is also in the spirit of Edward Abbey, who tossed beer cans from his pickup truck and claimed that the highway, not his littering, constituted the real defacement. A littering environmentalist, a philandering family man, and a Westerner raised in Pennsylvania, Abbey was a catalog of contradictions and inconsistencies. Gessner glosses this complexity with a hopeful spin: “He is a big fat hypocrite and he admits it, and there is something cleansing about this… It does offer the hope that one does not have to be pure to fight.”

Recommended: 10 best books of April: the Monitor’s picks

This is good news; there would be few activists in the world if any hypocrisy invalidated their achievements. Though Abbey’s passion is easy to admire, his methods were often wildly unorthodox. His novel “The Monkey Wrench Gang” celebrates the particular brand of idealistic sabotage that Abbey and his friends largely invented: they sawed down billboards, poured sugar into the gas tanks of bulldozers, and schemed to blow up bridges. These tactics typically only delayed development, but they thrust environmental issues into the national conversation and focused public attention on the despoliation of fragile ecosystems.

10 best books of April: the Monitor’s picks

Wallace Stegner took a more measured approach to both life and conservationism. In fact Abbey criticized Stegner for his “excess of moderation.” But Stegner was undeniably effective. He not only worked on legislation that became the landmark 1964 Wilderness Bill, he also helped to create Utah’s Canyonlands National Park. Unlike Abbey, Stegner had the patience to do the unglamorous work of sitting on committees, meeting with politicians, and galvanizing public support. Writing novels was his deepest pleasure and aspiration, but he regarded environmental activism as an essential duty.

Eastern intellectuals often ignored and belittled Stegner and Abbey. The New York Times Book Review didn’t even review Stegner’s 1971 novel, “Angle of Repose,” but they did find the space for an essay that objected to the book winning the Pulitzer Prize. Both men resisted designation as merely regional writers, arguing that the real provincialism belonged to those critics who, in Stegner’s phrase, “make the New Yorker’s mistake of taking New York for America.”

A devoted readership in the millions is one measure of both men’s literary influence. Gessner notes that nearly every park ranger in the American West has a dog-eared copy of Abbey’s classic nonfiction book “Desert Solitaire,” a meditative account of the year that Abbey spent as a ranger at Arches National Monument near Moab, Utah. And his works still occupy whole shelves at the Moab local bookstore, where he’s by far the best-selling author.

Stegner, in turn, exercised a whole other order of influence. After founding Stanford’s Creative Writing Program in 1945, he taught many future luminaries who attended the program: Ken Kesey, Larry McMurtry, Raymond Carver, Wendell Berry, and Edward Abbey, to name a few.

One advantage of writing biography about subjects who lived recently is that surviving friends and family can supply fantastic source material. Gessner chats with Wendell Berry in Kentucky, visits in Utah with the man who inspired the character Seldom Seen Smith in “The Monkey Wrench Gang,” and drives to Stegner’s old house in California. Gessner is a dedicated sleuth and an engaging guide to the human and natural terrain.

He also moves beyond Stegner and Abbey to report on recent transformations in the land that they loved. Especially interesting is his account of Vernal, Utah, a fracking boomtown where property taxes and crime have risen in tandem with employment created by the new industry. Air quality has suffered, and millions of gallons of water are used in the process of extracting oil. The distribution of profits from the industry is highly unequal, its long-term viability dubious, and its environmental impacts disturbing.

Gessner places Vernal in the context of a broader historical trend of extracting wealth from Western states. Agriculture, mining, ranching, tourism, and fracking all reflect a particular view of the West as a resource-rich land of promise and plenty where anyone can strike it rich. This mythology of the West dangerously obscures the fact that its resources are finite and its ecosystems fragile.

Like the best works of Stegner and Abbey, Gessner’s book sands away the varnish of legend that casts the West in the unlikely role of American Eden. With human populations exploding, rivers dwindling, fires raging, and wildlife forced into ever smaller pockets of wilderness, the American West needs to move beyond deceptive myths of boundless plenty and heed what the philosopher Santayana once called “the sadness and discipline of the truth.”

April 25, 2015

April 24, 2015

The “All The Wild” Tour: Rough Draft!

Here is what I got so far. Pardon (or tell me to correct) any mistakes. Just wanted to get something down for now. Come on out and see me!

Here is what I got so far. Pardon (or tell me to correct) any mistakes. Just wanted to get something down for now. Come on out and see me!

Friday, 5/1: Ken Sanders Rare Books in Salt Lake City

Sunday, 5/3: 3 pm afternoon event at Bookworks in Albuquerque

Monday, 5/4: 7 pm Changing Hands event in Phoenix

Tuesday, 5/5: 7:30 pm event at Boulder Bookstore

Wednesday 5/6 Tattered Cover Denver, CO

Wednesday 5/6 Tattered Cover Denver, CO

Friday May 8. 7:30 pm. University of Oregon. Corvallis. Valley Library.

Saturday May 16. 7 – 8:30 PM.

Wenatchee Valley College Wenatchee, WA 98801

At the Grove, which is the recital hall at the Music and Arts Center:

Sunday May 17th Birdfest Leavenworth, WA ,

noon to 1:30 PM: talk osprey at the Wenatchee River Institute Barn Learning Center.

Monday 05/18: Portland 7 :30 PM POWELL’S BOOKSTORE

Tuesday 05/19: Seattle 7:00 PM ELLIOTT BAY BOOK COMPANY

Wednesday 05/20: Bellingham, Washington 7 :00 PM VILLAGE BOOKS

Thursday 05/21: Seattle THIRD PLACE BOOKS

Wednesday June 10

Collected Works Santa Fe, NM

Thursday June 11

Maria’s Bookstore Durango, CO

Friday June 12

Back of Beyond Moab, Utah

Saturday June 13

Reading Between the Covers

Telluride, CO

Thursday June 18

Bookworms of Edwards

Edwards, CO

June 21

Minnesota Northwoods Writers’ Conference 2015

Thurs July 16

Rumors Coffee and Tea

Crested Butte

Sat July 18

King’s English Salt Lake City

Tuesday July 21

Elk River Books

Livingston, Montana

Wednesday July 22

Bozeman, Country Bookstore

Friday July 24

Indigo Bridge, Lincoln, Nebraska

New events coming soon!

April 22, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday, Earth-Day Edition: Cross Borders!

Here was the phone conversation, as recounted later by my wife.

Here was the phone conversation, as recounted later by my wife.

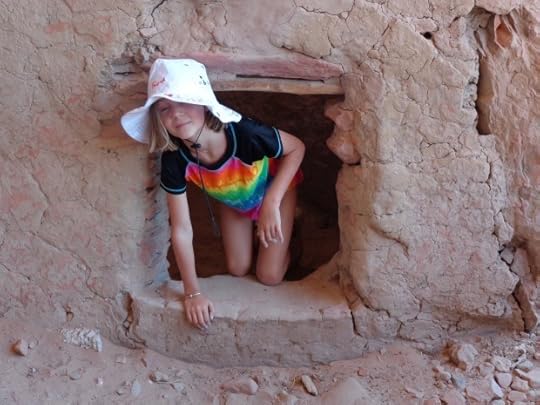

“Is this Nina de Gramont, mother of Hadley Gessner?’ asked the Canadian Border Officer.

“Yes it is.”

“Does Hadley Gessner have permission to cross into Canada with David Gessner?”

“Yes, she most certainly does.”

“Well, that’s good because they crossed the border about half an hour ago.”

Nina and I had been unaware that any single parent crossing the border with a child needs a letter from the absent parent. So Hadley and I ended up in the Border Patrol office, talking with the officer for close to an hour while he tried Nina’s phone again and again. At the end of that hour, the officer had learned some things, including how Labrador Retrievers got their name–they were originally from Newfoundland but that name was taken so they were named after the surrounding sea—and was also pretty sure that Hadley was not being kidnapped.

“I’ve got a girl in first grade myself so I’m a little more stringent than most of my co-workers,” he said. ”Ninety percent of all kidnappings are by a parent.”

Then he sent us off into the wilds of Canada without official spousal permission, but with some confidence that my intentions were not evil ones.

“I’ve got to warn you,” he said before we left. “It’s pretty desolate up there.”

He didn’t mean his whole country, but the stretch of Alberta that we would pass through as we headed north. Our first stop was only a hundred yards from the border office, to take a picture of the “Entering Alberta” sign, since Neil Young’s “Four Strong Winds” was Hadley’s favorite song and opens with the line: “Think I’ll go out to Alberta….” Once we got on the road we found that desolate was exactly the right word. We didn’t pass any other cars as we drove up through the endless albino wheat fields, and when we turned off on a dirt and gravel road east toward Saskatchewan, rocks started kicking up under the car.

Hadley and I were traveling together after she and Nina had come to spend a week with me during the western trip that became my current book. After the week they both had tickets to fly back from Denver to North Carolina, but only Nina used her’s. She had a book to finish (an origin story for the Rogue character of X-Men fame called Rouge Touch) and so we decided that Hadley would join me for the final leg of my adventures. Less than forty eight hours after Nina left, Hadley and I were spending the night in the trailer behind Doug Peacock’s house in Emigrant, Montana. Another forty eight and we were crossing into Canada to visit Wallace Stegner’s home in the town of Eastend.

Hadley and I were traveling together after she and Nina had come to spend a week with me during the western trip that became my current book. After the week they both had tickets to fly back from Denver to North Carolina, but only Nina used her’s. She had a book to finish (an origin story for the Rogue character of X-Men fame called Rouge Touch) and so we decided that Hadley would join me for the final leg of my adventures. Less than forty eight hours after Nina left, Hadley and I were spending the night in the trailer behind Doug Peacock’s house in Emigrant, Montana. Another forty eight and we were crossing into Canada to visit Wallace Stegner’s home in the town of Eastend.

This is the traditional point in this sort of blog where I turn from scene and story to metaphoric lesson, and who am I to buck tradition? Let’s keep this one simple. There is always some danger, and usually even more trepidation, when crossing borders. Of course I was never that worried with the Canadian Border Officer, certainly not like I had been when sneaking into Cuba or birding in Venezuela. But there was still energy to it. The book that I was writing involved more than a few border crossings of its own, as I cut back and forth between travel writing, memoir, biography, nature writing and literary criticism. Those more literary crossing were not going to land me in jail, but they were still dangerous in their own way. It is the sort of danger that I have been urging my grad students to court.

I have said more than once in this blog that we are at a thrilling time to be a writer of nonfiction. There are so many possibilities, so many genre combinations. That is why, though I am a lover of memoir, that I grow frustrated when 99.9% of what I see in the workshops I teach is really just memoir. Memoir is great, wonderful, but what about crossing a few borders? What about adding some reporting to your memoir, for instance? What about crossing into new and dangerous ground?

You can even edge into it and begin slowly by crossing into a metaphoric Canada. But do start crossing. You will find things you have never seen before, things that you have never expected.

Oh, and maybe next time I’ll tackle going down the metaphoric river:

April 21, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “All the Wild That Remains,” by David Gessner

The natural world is out of balance. That much is clear to all but the most myopic among us. Global warming, annual ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ weather events, water scarcity, toxic pollution, species extinction… the list is a depressing drumbeat foretelling catastrophe. Yet despite this impending crisis the environmental movement seems to have lost its mojo. Where are the iconic leaders of this generation, the Ed Abbeys and the Wallace Stegners, wordsmiths who could awaken a movement with their well-chosen words?

The answer might partly be found in David Gessner’s brilliant new work, All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. Gessner argues eloquently and compellingly that Stegner and Abbey are still relevant and resonant today and we ignore their pleas at our peril. The author gives particular attention to the warnings issued by both men regarding the fragility of the American West; though recent, anomalous wet spells may have deluded many into misperceiving the area as a land of fertile plentitude, the truth is that much of the American West is semi-arid and relatively barren of water. Treating it otherwise, Abbey and Stegner and now Gessner point out, is a fool’s errand that will have disastrous consequences for the region and the hordes that want to live there.

The answer might partly be found in David Gessner’s brilliant new work, All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. Gessner argues eloquently and compellingly that Stegner and Abbey are still relevant and resonant today and we ignore their pleas at our peril. The author gives particular attention to the warnings issued by both men regarding the fragility of the American West; though recent, anomalous wet spells may have deluded many into misperceiving the area as a land of fertile plentitude, the truth is that much of the American West is semi-arid and relatively barren of water. Treating it otherwise, Abbey and Stegner and now Gessner point out, is a fool’s errand that will have disastrous consequences for the region and the hordes that want to live there.

In the course of the book author Gessner deftly dons many hats: biographer, road warrior, memoirist, tourist, historian, doting father, uxorious husband, scholar, scientist and philosopher, with each perspective offering a slightly altered view of our relationship with the land. Though at first glance the central figures in the book could have not have been more unalike, Gessner suggests we look a bit deeper, beyond the superficial depiction of Stegner as the staid, conservative academic and Abbey as the unrepentant and wild rebel of the movement. If there is an agenda to Gessner’s travels it develops around visits with many of the friends, colleagues and family of the two men; indeed, the insights gleaned from these conversations are what animate the narrative. One of the book’s first stops is a pilgrimage to the Kentucky farm of Wendell Berry, who knew both Abbey and Stegner well. For the remainder of his travels author Gessner returns returns again and again to Berry’s dictum to interrogate how the land is being used… is it appropriate? Is it sustainable? In regards to the American West, the answer is often no.

But the truly sublime pleasure in this marvelous book grows out of the author’s invitation to accompany the peregrinations of his lively, inquisitive intellect and his attempts to discern where we are at in our relationship with the natural world. In the eminently capable hands of a writer who has honed his craft for half a lifetime, the narrative often evokes the feel of a float trip through canyonland–often mesmerized by the beauty of the land, the reader is yet always alert to whatever lies around the next bend.

Gessner is also startlingly honest, describing much of Abbey’s fiction as ‘cartoonish‘ and floating the claim, true or not, that one of Stegner’s most famous pupils based a certain Nurse Ratched from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest upon his very tightly buttoned up professor. But mostly he has tremendous admiration for the men and their work, pointing to Abbey’s Desert Solitaire as a seminal masterpiece on a level with Walden and applauding Stegner’s environmental victories, including his central role in preserving the Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado. In the end Gessner’s new manifesto argues that the work before us is to recalibrate and redefine how we interact with the physical world. Though the ship may be irrevocably listing and sinking the work must go on Gessner argues, because we owe it both to the legacy of Cactus Ed and Wally Stegner and to the generations that will come after us.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

Lundgren’s Lounge: “All That Remains,” by David Gessner

The natural world is out of balance. That much is clear to all but the most myopic among us. Global warming, annual ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ weather events, water scarcity, toxic pollution, species extinction… the list is a depressing drumbeat foretelling catastrophe. Yet despite this impending crisis the environmental movement seems to have lost its mojo. Where are the iconic leaders of this generation, the Ed Abbeys and the Wallace Stegners, wordsmiths who could awaken a movement with their well-chosen words?

The answer might partly be found in David Gessner’s brilliant new work, All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. Gessner argues eloquently and compellingly that Stegner and Abbey are still relevant and resonant today and we ignore their pleas at our peril. The author gives particular attention to the warnings issued by both men regarding the fragility of the American West; though recent, anomalous wet spells may have deluded many into misperceiving the area as a land of fertile plentitude, the truth is that much of the American West is semi-arid and relatively barren of water. Treating it otherwise, Abbey and Stegner and now Gessner point out, is a fool’s errand that will have disastrous consequences for the region and the hordes that want to live there.

The answer might partly be found in David Gessner’s brilliant new work, All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. Gessner argues eloquently and compellingly that Stegner and Abbey are still relevant and resonant today and we ignore their pleas at our peril. The author gives particular attention to the warnings issued by both men regarding the fragility of the American West; though recent, anomalous wet spells may have deluded many into misperceiving the area as a land of fertile plentitude, the truth is that much of the American West is semi-arid and relatively barren of water. Treating it otherwise, Abbey and Stegner and now Gessner point out, is a fool’s errand that will have disastrous consequences for the region and the hordes that want to live there.

In the course of the book author Gessner deftly dons many hats: biographer, road warrior, memoirist, tourist, historian, doting father, uxorious husband, scholar, scientist and philosopher, with each perspective offering a slightly altered view of our relationship with the land. Though at first glance the central figures in the book could have not have been more unalike, Gessner suggests we look a bit deeper, beyond the superficial depiction of Stegner as the staid, conservative academic and Abbey as the unrepentant and wild rebel of the movement. If there is an agenda to Gessner’s travels it develops around visits with many of the friends, colleagues and family of the two men; indeed, the insights gleaned from these conversations are what animate the narrative. One of the book’s first stops is a pilgrimage to the Kentucky farm of Wendell Berry, who knew both Abbey and Stegner well. For the remainder of his travels author Gessner returns returns again and again to Berry’s dictum to interrogate how the land is being used… is it appropriate? Is it sustainable? In regards to the American West, the answer is often no.

But the truly sublime pleasure in this marvelous book grows out of the author’s invitation to accompany the peregrinations of his lively, inquisitive intellect and his attempts to discern where we are at in our relationship with the natural world. In the eminently capable hands of a writer who has honed his craft for half a lifetime, the narrative often evokes the feel of a float trip through canyonland–often mesmerized by the beauty of the land, the reader is yet always alert to whatever lies around the next bend.

Gessner is also startlingly honest, describing much of Abbey’s fiction as ‘cartoonish‘ and floating the claim, true or not, that one of Stegner’s most famous pupils based a certain Nurse Ratched from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest upon his very tightly buttoned up professor. But mostly he has tremendous admiration for the men and their work, pointing to Abbey’s Desert Solitaire as a seminal masterpiece on a level with Walden and applauding Stegner’s environmental victories, including his central role in preserving the Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado. In the end Gessner’s new manifesto argues that the work before us is to recalibrate and redefine how we interact with the physical world. Though the ship may be irrevocably listing and sinking the work must go on Gessner argues, because we owe it both to the legacy of Cactus Ed and Wally Stegner and to the generations that will come after us.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. ]

April 20, 2015

The Spill and the Drought: Restraint, Regulation, and This Beautiful Country

Today is a doubly significant day for me. It is both the pub day for my new book about the American West and the fifth anniversary of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the pleasures of writing the book was spending a few years studying not just the work but the thinking of Wallace Stegner, and Stegner wouldn’t have wasted too much time making the connection between the drought in California and the spill in the Gulf. That they can be connected, and not just by the one-size-fits-all cudgel called climate change, seems obvious enough. Both events push us to think harder about resources and energy, not in a cliche or soft manner but in a real way, and in both cases both are deeply tied to the specific geographies of the places: one a near-desert that has long been in denial about its own aridity, and the other a near-tropical wonderland that has been long treated as a dumping ground and resource colony.

Today is a doubly significant day for me. It is both the pub day for my new book about the American West and the fifth anniversary of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. One of the pleasures of writing the book was spending a few years studying not just the work but the thinking of Wallace Stegner, and Stegner wouldn’t have wasted too much time making the connection between the drought in California and the spill in the Gulf. That they can be connected, and not just by the one-size-fits-all cudgel called climate change, seems obvious enough. Both events push us to think harder about resources and energy, not in a cliche or soft manner but in a real way, and in both cases both are deeply tied to the specific geographies of the places: one a near-desert that has long been in denial about its own aridity, and the other a near-tropical wonderland that has been long treated as a dumping ground and resource colony.

As I thought about the two places, after dropping my daughter off at school, I also found myself thinking about that most un-sexy and un-American of topics: regulation. When conservatives rail against “regulation” they are tapping into a very deep vein in the American psyche. It is an American myth that we still are what we once were. To put it in psychological terms, it is the desire to be young again. To be a muscular young country that spilled over with resources to be exploited and land where few lived. To continue the metaphor, moderation is to the human life what regulation is to the country’s. As you get older you know your limits. You use discipline and restraint, tools to make the best out of what you now have. Of course the myth of limitlessness–no restraint necessary!–is a lot more exciting. It’s no wonder many still cling to that dream instead of looking our reality in the eye.

I was back down in the Gulf this past January and will be writing an article on the state-of-the-Gulf for Audubon magazine that will come out in early summer. At first we, caught up in the anniversary fever that seems to have gripped the news world, planned on having it come out this month. But for several reasons, some practical and some more philosophical, we decided to wait. Which means that I will be out in the thirsty west when I finish the piece on oil-soaked Gulf while checking in to see how the beginning of the new hurricane season is proceeding back on the southeast coast. That all these places are unique, and yet all connected, is perhaps too simple to repeat. As is a fact that anyone who really spends time in these places– and not just perusing editorial pages or on-line screeds–can tell you: this is still a beautiful, beautiful country. Will it still be in a hundred years? Two hundred? I suspect the answer will depend less on what we are able to do than on what we are able to keep ourselves from doing.

David Gessner is the author of All the Wild that Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West, due out today.

April 19, 2015

Salon’s Excerpt This Sunday Morn

Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey have never been more relevant in the drought-stricken West

In this overheated, overcrowded world, the books of these “reluctant environmentalists” can be our guides

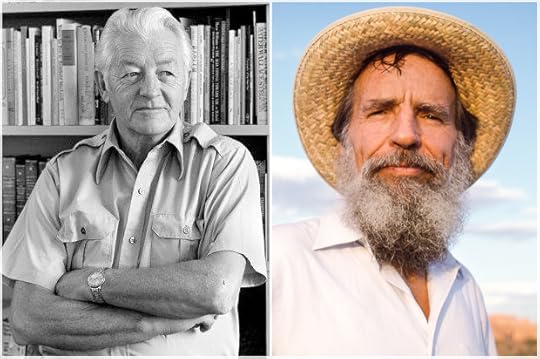

EnlargeWallace Stegner, Edward Abbey (Credit: Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service; Susan Lapides)

EnlargeWallace Stegner, Edward Abbey (Credit: Chuck Painter/Stanford News Service; Susan Lapides)It was 2012, a summer of fires and fracking. The hottest summer on record, they said, with Midwest cornfields burnt crisp and the whole West aflame, a summer when the last thing a card-carrying environmentalist would want to be caught dead doing was going on a nine-thousand-mile road trip through those parched lands.

I was going anyway. For almost a decade I had dreamed of getting back out West, where I had lived during my early and mid-thirties, and as it happened the summer I picked was the one when the region caught fire. Just like today drought was the word on everyone’s dry lips, and there was another phrase too—“the new normal”—that scientists applied to what was happening, the implication being that this sort of weather would be sticking around for a while. Though I hadn’t planned it that way, I would be driving out of the frying pan of my new home in North Carolina and into the fire of the American West. In Carolina, I had been studying the way hurricanes wracked the coast, but now I would be studying something different. Though my hurricane-magnet hometown’s problem was too much water, not too little, I had the sense these things were connected.

I loved the West when I lived there, finding it beautiful and inspiring in the way so many others have before me, and at the time I thought I might live there for the rest of my life. But circumstances, and jobs, led me elsewhere. It nagged me that the years were passing and I was spending them on the wrong side of the Mississippi. But I followed the region from afar, the way you might your hometown football team, and the news I heard was not good. A unique land had become less so, due to an influx of people that surpassed even the Sunbelt’s. The cries of “Drill, Baby, Drill!” might be loudest in the Dakotas, but they echoed throughout the West. The country’s great release valve suddenly seemed a place one might long to be released from. And now the fires, biblical fires, wild and unchecked, were swallowing up acreage comparable to whole eastern states.

It was a summer much like this summer promises to be, with historically low snowpacks, in the Sierras this time, not the Rockies, and early fires. READ THE REST AT SALON.COM