David Gessner's Blog, page 19

April 18, 2015

April 17, 2015

From Amazon’s Ominivoracious Blog: Wild Ed and Straightlaced Wally

This went up today at Amazon’s Omnivoracious blog, from the editor Jon Foro:

This went up today at Amazon’s Omnivoracious blog, from the editor Jon Foro:

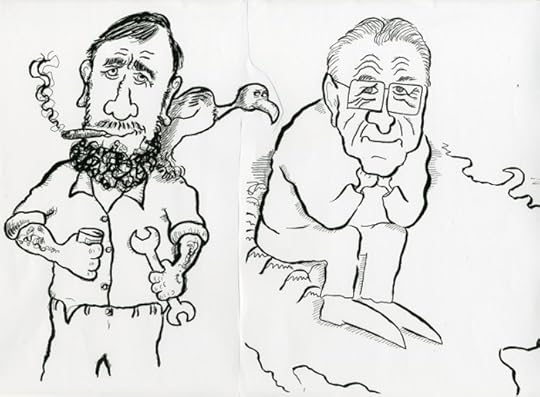

Among Western authors–those who write about the West, that is–it’s arguable that none stand above Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey. At the very least, no two writers presented such antithetical personas: Stegner, the buttoned-down professor and family man dedicated to discourse and process, vs. Cactus Ed, Stegner’s former pupil and irascible, impatient anarchist, who fought all development as despoilment.

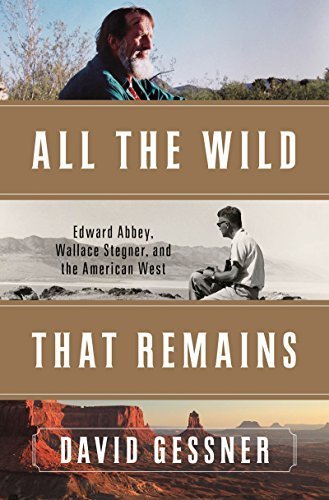

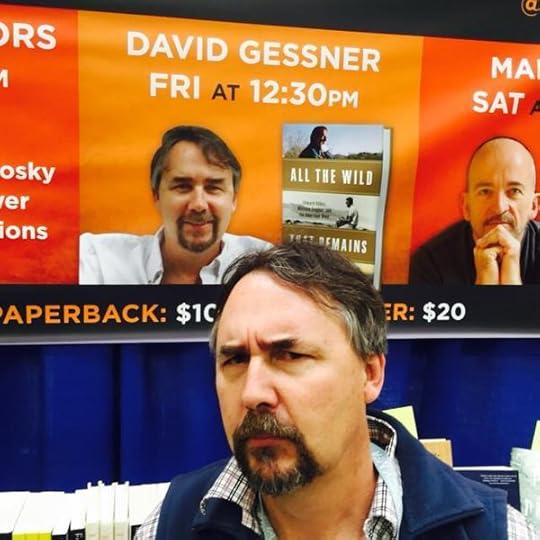

But can you judge these books by their covers, or even by their books? Award-winning nature writer David Gessner wasn’t sure, so he lit out to the land they called home (if not always), searching for the truth beyond their iconic images. The result will appeal to fans of both authors: All the Wild That Remains is an entertaining, illuminating travelogue, as well as a thoughtful examination of the complicated men and their legacies across modern landscapes.

But can you judge these books by their covers, or even by their books? Award-winning nature writer David Gessner wasn’t sure, so he lit out to the land they called home (if not always), searching for the truth beyond their iconic images. The result will appeal to fans of both authors: All the Wild That Remains is an entertaining, illuminating travelogue, as well as a thoughtful examination of the complicated men and their legacies across modern landscapes.

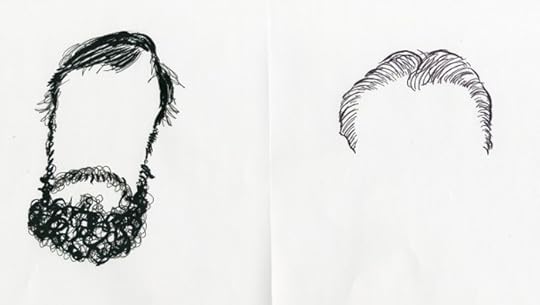

Here Gessner contrasts the two giants of Western literature, starting at the top with with the most conspicuous, if superficial, difference: their chosen hairstyles. All the Wild That Remains is an April 2015 selection for Amazon.com’s Best Books of the Month in Nonfiction.

Of Canyonlands and Coiffures: Abbey and Stegner’s Contrasting (Hair)Styles

by David Gessner

There’s more than one way to fight for the environment and more than one style. This was a point that kept being driven home during my travels through the American West for my new book, All The Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West. It was driven even deeper during my three years of researching and writing the book, as I began to learn more about the lives and work of two of our country’s greatest 20th century writer-environmentalists. I believe that Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey provide models for the rest of us, like human signposts, though at first the signs sometimes seem to be pointing in opposite directions.

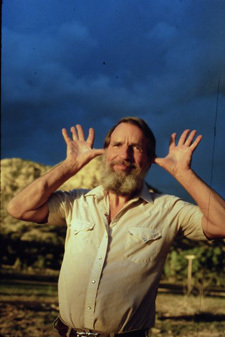

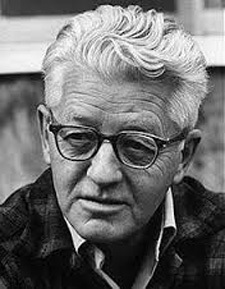

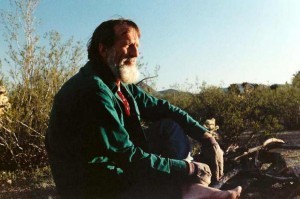

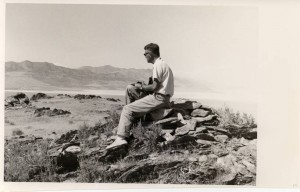

One of the fun parts of writing the book was comparing and contrasting Stegner and Abbey. I didn’t want to caricature them (except when drawing actual caricatures like the ones above) but there they were: the proper, virtuous, almost regal Stegner, on the one hand, married to the same woman for 59 years, and on the other the wild, self-proclaimed monkey-wrenching anarchist, Abbey, who had five children with five wives. It got to the point while writing the book that I felt I could write a whole chapter by simply contrasting the two men’s hairstyles:

There were plenty of other fun methods of contrasting as well. One was their different attitudes toward the river trips they took. Abbey, near the end of a ten day paddling trip on the Colorado, wondered if he could just stop and live there forever, roaming the side canyons, wandering naked, shooting deer and drinking river water, seeing no one. Stegner on a similar trip, also fantasized about an extended stay in the canyon, but with one telling addition: he thought it would be a great place to roll up his sleeves and write a book.

Work, and its deep pleasures, was always a touchstone for Stegner. Meanwhile part of the appeal of Ed Abbey, I’ve come to believe, is that he understood the lost art of lounging. Here he is in Desert Solitaire: “I was sitting out back on my 33,000 acre terrace, shoeless and shirtless, scratching my toes in the sand and sipping on a tall iced drink, watching the flow of the evening over the desert.”

Shop this article on Amazon.com

All the Wild That Remains

David Gessner

Virtue, outside of the virtue of saving wild places, doesn’t have much of a role in Ed Abbey’s work, and do-gooders are frowned upon. Meanwhile sensual pleasure, which plays such a large role in Abbey’s life and writing, goes virtually unmentioned in Stegner’s.

I began to think that we read Wallace Stegner for his virtues, but we read Edward Abbey for his flaws. Stegner the sheriff, Abbey the outlaw.

I remember an essay written by the editor and essayist Rust Hills about Michel de Montaigne and Henry David Thoreau. “Montaigne is somehow marvelously humanly indolent; Thoreau had an exceptional, almost inhuman, vitality,” he wrote. “Thoreau kept in shape….” What does he mean by this? He means that Thoreau, though famous as someone who retired from the active world, worked vigorously on himself and his art, walked hard (four hours) each day, wrote in his journal, striving for a higher, better life. Montaigne in contrast, accepted his sloppy self. The song he sang was: “This is me. Take me as I am. I do.”

Abbey, of course, plays the Montaigne role here, and while Stegner may at first seem miscast in the Thoreau role, this particular aspect of Thoreau fits well. With Stegner, there is always a sense of vigor, fitness, striving to be more.

This came through in the way they fought for the planet. While Stegner’s political thinking was more sophisticated and restrained, Abbey’s words had a rare attribute: they made people act. Monkeywrenching, or environmental sabotage, has recently been lumped together with terrorism, but Abbey could make it seem glorious. After finishing a chapter or two, readers would want to join his band of merry men, fighting the despoiling of the West by cutting down billboards and pulling up surveyors’ stakes and pouring sugar into the gas tanks of bulldozers, all of this providing a rare example of true literary influence at work.

Abbey wrote from two sources: love and hate. He said as much, claiming that a writer should be, “Fueled in equal parts by anger and love.” He had fallen in love with a place and he wrote paeans to those places while cursing those who were trying to despoil what he loved.

Abbey wrote from two sources: love and hate. He said as much, claiming that a writer should be, “Fueled in equal parts by anger and love.” He had fallen in love with a place and he wrote paeans to those places while cursing those who were trying to despoil what he loved.

He wouldn’t have used the word “despoil” of course. He would have chosen, as he often did, the more direct and blunt “rape.” And why not? The enemy was aggressive, rapacious, never resting. In response he had to be the same. Words were his first line of defense, maybe his last, and he piled them up like a barricade of rubble. Though he could be brutally concise, he was also a hyperbolist, and like Thoreau, varied between these two extremes. Both an embracer of excess and a blunt blurter. Either way the words seem to have been summoned directly from and in defense of the land. His is not the effort of a stylist.

If Abbey didn’t despise with such passion his would be just run of the mill curmudgeonly grumbling. In Abbey’s world Lake Mead, Lake Powell’s downstream cousin that was created by the Hoover Dam, is “a stagnant cesspool” and “a placid evaporation tank,” while the cars that tourists drive in are “upholstered mechanized wheelchairs.” He writes: “With bulldozer, earth mover, chainsaw and dynamite the international timber, mining, and beef industries are invading our public lands—bashing their way into our forests, mountains and rangelands and looting them for everything they can get away with.” “Mr. Abbey writes as a man who has taken a stand,” was how Wendell Berry once put it.

This is both instinctive and the result of a thought-out philosophy. “It is my belief that the writer, the free-lance author, should be and must be a critic of the society in which he lives,” is how Abbey begins “A Writer’s Credo.”

He continues:

“Am I saying that the writer should be–I hesitate before the horror of it–political? Yes sir, I am…..By ‘political’ I mean involvement, responsibility, commitment: the writer’s duty to speak the truth–especially unpopular truth. Especially truth that offends the powerful, the rich, the well-established, the traditional, the mythic, the sentimental.”

If Abbey was Mr. Outside, then Stegner was Mr. In.

Here is what Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt said about Stegner’s biography of John Wesley Powell:

When I first read Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, shortly after it was published in 1954, it was as though someone had thrown a rock through the window. Stegner showed us the limitations of aridity and the need for human institutions to respond in a cooperative way. He provided me in that moment with a way of thinking about the American West, the importance of finding true partnership between human beings and the land. (FN: 208 JB)

Even Ed Abbey, who may not have even liked Stegner that much, said of him: “Wallace Stegner is the only American writer who deserves the Nobel Prize.”

That these words did not come from a student trying to butter up a teacher—who could be more antithetical to wild Ed than the older, buttoned down, conservative, hippie-hater?—make them carry even more weight. Abbey admired Stegner’s work and his commitment to making art, but perhaps admired more his teacher’s commitment to fighting for the land.

At the urging of his friend, the writer Bernard DeVoto, Stegner began to write a series of environmental articles in the early ‘50s, and those articles were read by David Brower, the charismatic single-minded executive director of the Sierra Club. Brower recruited Stegner to edit a book that would describe the wonders that would be lost if a dam were built within the borders of Dinosaur. In their successful campaign to stop the dam the two men would not just help win a battle but would revolutionize the way environmental fights were waged. Until the effort to save Dinosaur there had been something upper crust and musty about the Sierra Club and the other environmental organizations, but with Dinosaur they would go from fuddy-duddys to fighters. Over the next decade great gains would be made and a new style forged: full page ads would be taken out in major papers comparing the damming and drowning of the Grand Canyon to the flooding of the Sistine Chapel, beautifully photographed books would help change our national consciousness, park land would be purchased as it hadn’t been since the days of Teddy Roosevelt, culminating with the Wilderness Act.

In 1960, Stegner published his soon-to-be-famous “Wilderness Letter,” which argued that wilderness was vital to the American soul, and that undeveloped land was deeply valuable, even when that value was not obvious and monetary. One influential reader of the letter was the new Secretary of the Interior, Stuart Udall who thought so highly of it that he read it out loud at a Sierra Club gathering in April of 1961. By then he had also read Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, and he was determined to get Stegner to come to Washington with him. Stegner was reluctant; he was a writer with work to do, not a politician, but eventually he gave in. In D.C., he worked on the beginnings of legislation that would become 1964’s ground-breaking Wilderness Bill and attended meetings with Udall, during which, according to the Secretary, Stegner was “never bashful.” The eventual bill was in fact an almost perfect practical embodiment of the “Wilderness Letter,” a massive setting aside of lands never to be developed. For Stegner it was a heady experience, and he got “an inside look at parts of the Kennedy administration during its first energetic year” as well as “a good lesson in how long ideas that on their face seemed to me self-evident and self-justifying could take to be translated into law.” He also went on a vital reconnaissance mission to Utah for Udall, scouting the land that the Secretary would eventually save as Canyonlands National Park.

But the truth is Stegner only lasted four months in Washington. At heart he was not a politician but a writer and teacher. Mary Stegner found D.C. cold and lonely, and by the beginning of the spring term they were back at Stanford. His relationship with Udall would continue, however, and he would help the politician write the early drafts of what was to become Udall’s best-selling conservation manifesto, The Silent Crisis. And for the rest of his life Stegner would keep fighting in the environmental wars despite the fact that these obligations “constantly prevented the kind of extended concentration a novel demands.” It would have been nice to have turned his back on these extra obligations, but of course, being who he was, he couldn’t.

For Stegner, who always valued results above mere theory, efficacy was a great virtue. Or maybe it is best to say that he valued real-world effectiveness along with theory, broad ideas applied to the practical earth.

For Stegner, who always valued results above mere theory, efficacy was a great virtue. Or maybe it is best to say that he valued real-world effectiveness along with theory, broad ideas applied to the practical earth.

Overworked as he was, Stegner’s could sometimes be a grumpy goodness. In a fascinating exchange of letters with the beat poet and environmental guru, Gary Snyder, Stegner argues for the less exotic virtues of the cultivated western mind versus the enlightened eastern one. This included the importance of doing what one should and not what one felt like. In a letter dated January 27, 1968, he wrote: “I have spent a lot of days and weeks at the desks and in the meetings that ultimately save redwoods, and I have to say that I never saw on the firing line any of the mystical drop-outs or meditators.”

He went to those meetings because it was the right thing to do. An obligation, yes, but one he valued.

“The highest thing I can think of doing is literary,” he wrote a friend. “But literature does not exist in a vacuum, or even in partial vacuum. We are neither detached nor semi-detached, but linked to the world by a million interdependencies. To deny the interdependencies, while living on the comforts and services they make possible, is adolescent when it isn’t downright dishonest.”

Which meant sitting in at those boring meetings where he saw no mystical drop-outs or meditators. And giving talks, writing articles, and even propaganda when he would have rather been immersing himself deeply in a novel. He sometimes grumbled about this, of course he did. It was extra work, yet another thing-to-do in a life full of them. But he had signed on and he wouldn’t ever really sign off. Like Major Powell, he knew the despoilers, the extractors, would never rest. You never really “won” an environmental battle, after all, just saved places that would be fought over again in the future. Since the boomers never rested he knew that meant he could do very little resting himself. Unlike many of us today, he did not take environmentalism for granted, since when he had begun to fight it barely existed. Stegner concludes his “A Capsule History of Conservation” this way:

“Environmentalism or conservation or preservation, or whatever it should be called, is not a fact, and never has been. It is a job.”

So he did his job.

As did his former student, Ed Abbey, albeit in a very different way. Though he was a very different man than his old teacher, they had common ground. For Abbey and Stegner that ground was the earth itself, a place they both loved and were willing to fight for.

April 16, 2015

A Letter to Readers as Pub Date Approaches

Dear Readers,

Dear Readers,

As western rivers dry up and western land cracks from aridity, the voices of Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey have never been more important. At a time of fires and record low snowpack in the Sierras, with water beginning to be seen as the lifeblood it is, Stegner and Abbey can teach us that this has always been the reality of the West, not the myth we have been taught to believe in. They can show us how our way of inhabiting the region has never been sustainable, that today’s fracking is yesterday’s mining, and they can help us how the dots of the West have always connected: from aridity to the snowpack to water conservation to mining to a landscape unlike any other to an attitude toward that landscape that veers wildly from loving to rapacious. With climate change making a historically dry climate even drier, never has it been more vital to listen to what Abbey and Stegner have to tell us.

Those voices can be heard, loud and clear, in my new book about Abbey and Stegner, All the Wild that Remains. Last week The Christian Science Monitor came out with a top ten list and declared All the Wild That Remains their top book for April, joining Outside Magazine, Publishers’ Weekly and Kirkus (both starred reviews), Amazon, Powells and others in declaring it one of the most important books coming out this spring.

It is a book that both takes the long view of the land, and of the importance of having deep conversations with our literary ancestors, and that speaks to the crisis that is occurring right now. Stegner and Abbey put what is happening in historical perspective, but they were not detached scholars who sat back in a crisis. They both acted. They understood the land they loved, sure, but also fought for it. I hope my book inspires you to join in that fight, but also to think your way toward a deeper understanding of the connections in today’s world.

Please consider picking it up and giving it a read. For me Abbey was a gateway drug to Stegner. A great result for this book would be if for some it proved a gateway drug to both of these important and sometimes overlooked authors.

Sincerely,

David Gessner

Some nice things people have said so far about:

ALL THE WILD THAT REMAINS

W.W. Norton April 2015

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTSOvP4ej6g

“These revelations, and Gessner’s subtle humor, make for an absorbing read. Abbey’s and Stegner’s lives, Gessner says, ‘are creative possibilities for living a life both good and wild.’ That’s something that many in the West still seek–and what makes this book such a great read for anyone living there.”—Outside magazine http://www.outsideonline.com/1962281/new-reads-following-two-iconic-authors-west

The Christian Science Monitor picks All the Wild as their number one book of April. They write “Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey, two of America’s finest writers, were also staunch environmentalists and devoted advocates of the American West. In this engaging book, nature writer David Gessner follows in the tracks of both men, providing strong portraits of them as writers and as human beings (with sharply opposing characters and lifestyles) even as he pays moving tribute to the land they so deeply loved.” http://www.csmonitor.com/Books/2015/0403/10-best-books-of-April-the-Monitor-s-picks/All-the-Wild-that-Remains-by-David-Gessner

“Gessner writes with a vividness that brings the serious ecological issues and the beauty of the land into to sharp relief. This urgent and engrossing work of journalism is sure to raise ecological awareness and steer readers to books by the authors whom it references.”—Publishers’ Weekly. Starred Review. Here’s the full review: http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-0-393-08999-8

“Stegner and Abbey ‘are two who have lighted my way,’ nature writer Wendell Berry admitted. They have lighted the way for Gessner, as well, as he conveys in this graceful, insightful homage to their work and to the region they loved.”—Kirkus Review (Starred Review)

“This engaging book provides an intimate look at Edward Abbey (1927–89) and Wallace Stegner (1909–93), two of America’s finest authors, both of whom chafed at being pigeonholed as regional writers. Certainly their fond, passionate focus was the American West, but there is much universality in their concerns. Gessner (Return of the Osprey) traveled to places they haunted, read all he could of their writings, and spoke with people who knew them well. His smooth, literate text is enhanced by photographs of Stegner and Abbey as well as chapter notes that read well. Stegner authored 46 works, including 13 novels, and won a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Abbey wrote 28 books, was a Fulbright Scholar at Edinburgh University, and may be best known for his book Desert Solitaire, which is often said to be as worthy as Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. Stegner, clean cut, traditional, with a PhD, and Abbey, an uncompromising anarchist and atheist with a 1960s-ish appearance and lifestyle, provide rich grist for Gessner’s mill, which he fully exploits for the benefit of any reader. Gessner himself has penned nine books. All three authors qualify as important environmentalists and writers. VERDICT Highly recommended for everyone interested in literature, environmentalism, and the American West.”—Library Journal

ATWTR is now an editor’s pick at Amazon and a staff pick at Powell’s where Shawn writes: “All the Wild That Remains is a fascinating portrait of the American West told through the lives of two of its most famous writers, Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner. This book champions their unique styles and will make you want to read (or reread) all of their work. It will also inspire you to get your car and head out on an extended road trip through this beautiful western landscape.”

April 14, 2015

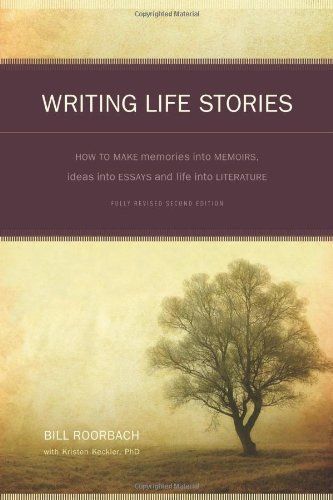

Bad Advice Wednesday: Teaching Creative Nonfiction? Here’s the Best Craft Book on the Market!

ISBN-13: 978-1582975276

Are you teaching writing? Is it about time to order books for fall semester? May I suggest Writing Life Stories? No reason to be humble–it’s the original and greatest book on making creative nonfiction–and the best by far, often imitated. And while it’s aimed at the creative writing crowd, it’s also very useful in the composition classroom, a complete course, and perhaps particularly suited to the community college setting, or anywhere non-traditional students appear, from high school to grad school and beyond. You get from it what you bring to it, in other words, and it self-adapts to whatever level the reader/writer/teacher approaches from. It moves seamlessly from Getting Started to writing memoir, then uses the memoir exercises as evidence for the writing of personal essays, then uses both to aim at public writing, including journalism and the formal essay. It’s got advice on publishing, too. It’s fun for students, which makes it fun for teachers, and it’s filled with exercises to do both in-class and on the fly, or to assign. Or for teachers who’d like to get some of their own writing done, goddamn it! The tenth anniversary edition, with Kristen Keckler, is thoroughly up to date, and replaces the old edition. Several sample essays form a mini-anthology, and the huge reading list in an appendix collecting great books in all creative nonfiction genres is famous, often borrowed! Among the many charms of Writing Life Stories is its price: $16.95, which means students actually afford to buy it, and most opt keep it. Plus, you know me! I’ll do an email chat with your class. I’ll walk to your university no matter where in the world, and I’ll talk to your class while you put your feet up and plot your novel!

“Bill Roorbach’s WRITING LIFE STORIES is brimming with valuable suggestions, evocative assignments, insights into the writing process, and shrewd common sense. I can’t wait to try some of this ideas in the classroom and on myself. This writing guide delivers the goods.”

–Philip Lopate, THE ART OF THE PERSONAL ESSAY

Writing Life Stories in Japanese

“WRITING LIFE STORIES is an inspiring way to begin writing a memoir. Roorbach is a fine author whose enthusiasm is infectious.”

–Lee Gutkin, Editor of Creative Nonfiction Magazine

“I would never have written word one without Bill Roorbach. It’s as simple as that.”

–Abigail Thomas, author of AN ACTUAL LIFE, GETTING OVER TOM, and A THREE DOG LIFE

“This is the book that I have been searching for for a long time. As a busy mom of three, I needed a “teaching book” that would give me concrete activities that I could work into my writing time. Reading this book and working on the subsequent “assignments” gives purpose to my very short writing time that I can squeeze into a day. If you are interested in writing memoir, but don’t know where or how to start…this is the book for you.”

–Logan Fisher

Writing Life Stories has changed my teaching. I’ve taught mostly ENG 101 and 102 classes at different universities (now at Arizona State), and I’ve always tried to supplement department books (which focus so heavily on ‘social issues’) with more creative ways to tap into inner voice and passion. My students always respond so positively to the chapters I use from your book; their topics are better, they have more confidence in their own experiences, and they finally admit to liking the readings I assign :). I’m an aspiring writer myself–mostly screenwriting at the moment and a teaching memoir. Aside from your book being great in and of itself, the conversations from the readings have helped me open up about my own writing process to students. This, I know, has allowed me to be expressive and show more of who I really am. I’m not being overdramatic when I say your book has been a big part in my development as a teacher and person. –Meghan Bacino

co-author for the tenth-anniversary edition, Kristen Keckler, PhD

Here are some quotes from GoodReads:

*****I’m reading this book in preparation for a class I’m teaching this fall. It’s a great guide to memoir writing. Breaks down writing technique into applicable, useful lessons. Writing exercises are useful and productive.–Sarah

*****This is now my new favorite writing book. I’ll keep the library copy until my own copy arrives and then carefully go through the 14 pages I folded the corners of and transpose them to my keeper. What amazes me is that there are ONLY 14 pages. In a book chock full of incredible coaching, there is also page after page of great tactics and sterling advice. Writing memoir is the hardest writing I’ve done and Bill’s book softens up the effort and lets me feel that yes, this is what I’m supposed to be doing. –Rena

First edition–Don’t use this one! the new one is thoroughly updated!

*****A great book for anyone interested in the Art and Craft of creative non-fiction. This one will have a permanent home on my desk to be referred to over and over again. –Elizabeth

*****An excellent and entertaining guide for writing aimed most specifically at memoir, although what it covers can be applied to forming any sort of story. Chris

*****loved this book. for someone terrified of writing (I avoided all essays and literature classes like the plague)this was a wonderful confidence builder. great ideas, great exercises, funny, helpful. I am glad I own it. –Teisha

*****There is a ton of information packed into this book. A ton. It is geared toward nonfiction writers, but even so a fiction writer can bring away a new way of looking at their writing. –Sarah G.

*****This is the best book about writing I’ve ever read. Roorbach explains gesture, scene and dialog so writers never forget these three basic elements of good writing. –Jean

“Writing Life Stories is a classic text that appears on countless creative nonfiction and composition syllabi the world over. This updated 10th anniversary edition gives readers the same friendly instruction and stimulating exercises along with updated information on current memoir writing trends, ethics, Internet research, and even marketing ideas. Readers will discover how to turn their untold life stories into vivid personal essays and riveting memoirs by learning to open up memory, access emotions, shape scenes from experience, develop characters, and research supporting details. With creativity sparking ideas from signing a form releasing yourself to take risks in your work to drawing a map of a remembered neighborhood, this book is full of innovative techniques that prove that real stories are often the best ones.” BarnesandNoble.com

April 13, 2015

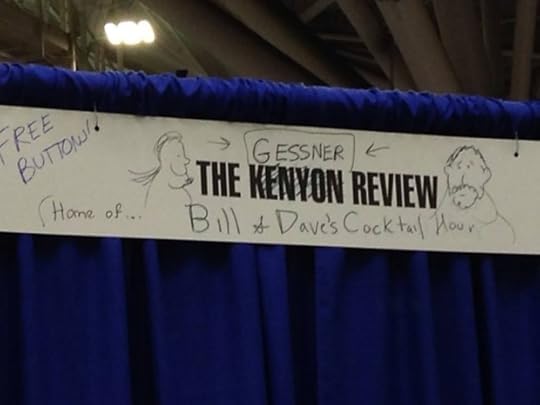

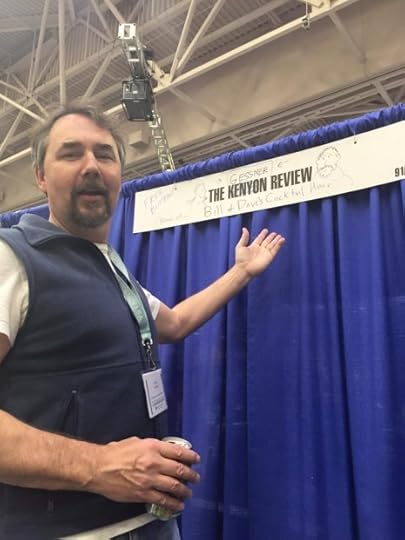

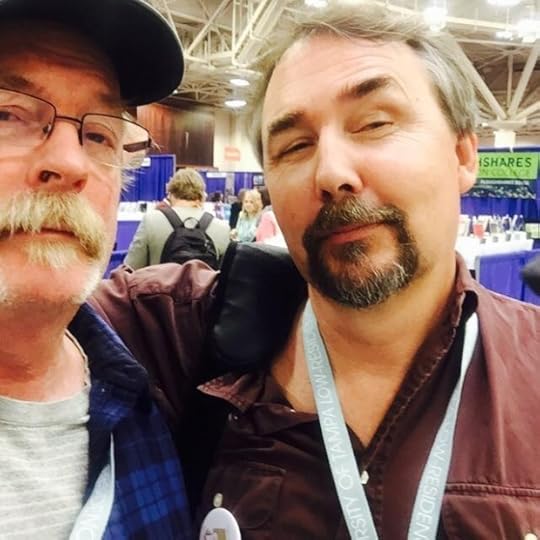

Pirates! Bill and Dave Take Over the Kenyon Review (Booth)

It was already late on Saturday of AWP when the Kenyon Reviewers decided it was time to pack up and head home to Ohio, foolishly leaving their booth unguarded. Bill and Dave are nothing if not opportunistic and swooped in to claim it as a place to hawk their wares. Soon the metaphors were flying along with the buttons (and flowing along with the wine). I initially suggested that we were hermit crabs finding an unused shell, or maybe cowbirds bullying our way into a nest. These nature-y metaphors, however, were not sexy and dashing enough for the sheer thrill of our conquest. Meg Reid suggested we “colonized” their territory, which I liked. But in the end piracy is the only word that will do. Argghhh! (I don’t have a picture but Long John Bill joined me after his afternoon nap.)

Booty!

Rubbing it in.

We celebrate after our coup!

Back on our island lair, plotting our next takeover.

April 11, 2015

Bill and Dave’s AWP Adventures

My goal today is to get hold of a microphone. And not for more pontificatin’. No, I’m talking SINGING. And here’s a couplet to give you a hint of the song I have in mind:

But if this ever-changing world in which we live in/makes you give in and cry…..

At the Norton booth. Scaring people off.

Pontificatin with arms flying. If I had my cartoon stuff I would draw thought bubbles over Alison, Chris and Ana Lena’s heads.

The real Bill and Dave. Sadly left at home this time.

Bill and Ted. So you don’t get us confused.

Everyone is reading it! (That’s Cora Fallon, daughter of Katie,who wishes she was here.)

April 1, 2015

Bad Advice Wednesday: Write Everything!

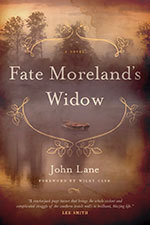

Somebody watching my writing career from outer space (or even a 12-foot step ladder) might suspect that I have some form of LADD, literary attention deficient disorder. Over the course of thirty-five years I have published books of poetry, individual short stories, journalism, literary nonfiction, personal essays, book-length narratives, book reviews, biographical entries, had a play produced, written a screen play that was optioned but never produced, worked for an industrial script writer, co-written songs for a rock-a-billy CD, coined advertizing copy for a billboard, and this month, finally waded into the saltwater marsh guarding the great ocean of long-form fiction by publishing my first novel, Fate Moreland’s Widow with USC Press’s new Story River imprint.

Somebody watching my writing career from outer space (or even a 12-foot step ladder) might suspect that I have some form of LADD, literary attention deficient disorder. Over the course of thirty-five years I have published books of poetry, individual short stories, journalism, literary nonfiction, personal essays, book-length narratives, book reviews, biographical entries, had a play produced, written a screen play that was optioned but never produced, worked for an industrial script writer, co-written songs for a rock-a-billy CD, coined advertizing copy for a billboard, and this month, finally waded into the saltwater marsh guarding the great ocean of long-form fiction by publishing my first novel, Fate Moreland’s Widow with USC Press’s new Story River imprint.

I didn’t plan to have a literary career, much less have it unfold this way by the time I turned sixty. When I was twenty-five I saw myself primarily as a poet and because of that, I didn’t see my choice as vocational. Nobody made a career out of poetry in 1979—except maybe Robert Bly, and I didn’t look good in a serape. Instead I considered what I was doing a calling. I even believed in the muses, particularly the muse of lyric poetry. Back in the Seventies, I believed the muse called for a stern steely-eyed focus on art. I believed she asked for total sacrifice, and particularly poverty. If I were to achieve any level of literary achievement, I would have to focus for years on the art of poetry alone. I would distill my voice and create with it a pure poetic acid to burn away all impurities of living a normal life. Or something like that.

So how to get there? How to find the time? The MFA programs were just taking off in the 1970s, so I didn’t go to graduate school right away; I did other things to support my calling—traveling, landing a grant to learn letterpress printing at Copper Canyon Press, working as a cook. I did not wear a beret, but it wouldn’t’ have surprised my friends if I had. As a twenty-something, I was that kind of poetry guy.

My “bad advice” back then would have been to write just one thing, and write it all the time, to go for Kierkegaard’s “purity of heart.” I might have might said, “Write only what you want when you want,” or, to crib a famous Joseph Campbell quote, “Follow your bliss into an endless mutating dance with your own creativity through time.”

But then my attention began to wander to other genres. I began to spread out. I jumped the out of the poetry channel; I discovered my flood plain was wide. I started reading Annie Dillard, Joan Didion, Edward Hoagland, and Barry Lopez and fell in love with their lyrical prose. By 1984 I’d published a bunch of poems in magazines and one small book, but I wanted to take a stab at emulating the prose writers I loved, and I found a magazine ready to pay me to write prose, the Sunday supplement for the largest circulation newspaper in South Carolina. The editor liked my poetry and said, “Write first person essays, and I’ll publish them.”

So I set about writing whatever occurred to me: a piece praising the lay-up over the dunk, a day’s worth of meals in a single town, a road trip from the mountains to the coast, a strange piece called “cloth confessions” about my love natural fabric shirts.

Once I’d begun writing prose fiction seemed the likely reach. I began to wonder: if Ed Abbey could write The Monkey Wrench Gang, Harry Crews Naked in the Garden Hills, Walker Percy The Moviegoer, and Clyde Edgerton Rainy, then why could I not write a novel too? I had stories. I could make up characters.

So at the same time I began to be seduced into first the emerging third-genre work by having a working relationship with a magazine to write what we now call “creative nonfiction” or the personal essay, I began my twenty-year apprenticeship in learning how to write a novel.

It wasn’t easy, but no one said it would be. The first novel I started was in the late 70s and was called The Sawgrass Rebellion, and it was sort of The Monkey Wrench Gang meets The Moviegoer, if you can imagine that. Its sensive young protagonist, Duncan Daniels, was a lot like me—a nature boy who read Kierkegaard, bent on saving the wild world world from the grasp of late stage Capitalism. I had about 130 type-written pages of that one when I abandoned it. No one ever saw it. I remained primarily a poet.

Next in the middle1980s I wrote an adventure novel with a close friend. It was called A Revolution of the Heart. Set in Belize, the protagonist (Peter Conrad) was just like my friend and co-writer, a crocodile biologist. The story owed a lot to one we admired, Heart of Darkness. Our hero Peter Conrad and his side-kicks battled drug-running poachers, another form of late-stages Capitalism. We finished the novel, landed an agent, and it was rejected twenty-seven times in New York.

Twenty-seven rejections wasn’t enough to stop me. In the late 1980s the agent convinced me to complete a novel about a high school basketball team during the integration of southern schools, something I’d experienced as a teenager. Called The Point Guard, I finished the manuscript, narrated by a 15-year-old player named, once again, Duncan Daniels. The book was set in a mythical town called Morgan, South Carolina, a post-textile community in the rolling hills east of the Blue Ridge, and it was about a friendship between Duncan and an African-American player on the team and their mutual struggle against a racist coach. The agent, upon first reading, was convinced it was an adolescent novel. I was not. He pitched it that way, and it soon out-paced A Revolution of the Heart in rejections.

The final attempt at a novel before I wrote and successfully placed Fate Moreland’s Widow was one a farce called Dirty Money. It did not contain a single character named Duncan Daniels, though I felt compelled once again to set it in my mythical Morgan County again, my personal Yoknapatawpha County. The story this time was about a small waste management company, late-stage Capitalism run amok once again. A man approaching eighty, the gullible but lovable Darrell Crosstie, had decided to give his fortune made in the garbage business to endow a local struggling college, only to find out as the action processed that he did not have any money to give because his crooked brother-in-law and business partner for decades had bamboozled him out of it and cleverly kept him in the dark long enough to deeply embarrass the college. A new agent read it and said, “I like it, but can’t you make it sound more like Carl Haasen?” More rejections. More failure

After Dirty Money took the dive into the rejection box, I began to feel a little like the King in Monty Python and the Holy Grail whose castle keeps falling in the swamp. But that didn’t’ stop me. Then I got an idea for another story, one about the earlier gritty stages of Capitalism—the story of a 80-year-old retired textile mill accountant and boss’s right-hand-man who one day in 1988 is plunged back into 1935-36, the most complex years of his long life by an unexpected visit, and Ben Crocker, the narrator of Fate Moreland’s Widow was born. After almost five years of drafts I sent the copy off to USC’s new novel series, and here I am—poet, short story writer, playwright, personal essayist, song-writer, script-writer, billboard author, and, finally, at the beginning of my seventh decade, and novelist.

It’s only been out a month, but what differences do I see so far? Donald Hall says publishing a book of poetry can feel like clapping in an empty room. I’ve found that publishing a novel feels much more like clapping in a very crowded room and wondering if anyone will hear you clap. As I wait for the applause or the boos, I have time to reflect on whether or not I should have tried to play that single note of poetry until I had it perfected. I think not. I have never been bored with writing. I have never had an attention deficient or a bad case of writers block because I’m always changing directions, sometimes in mid-stream, sometimes after I’m firmly standing on the far bank.

I have actually paid close attention—to the myriad ways the human imagination can express itself in writing. I’ve learned not to look down on the writer of multi genres, or to turn up my nose at those with a single fierce focus. So if you want to, write everything. There were plenty of bars to leap over, and no matter how many times you fail, remember how good it felt the last time to land in the sawdust on the other side.

March 31, 2015

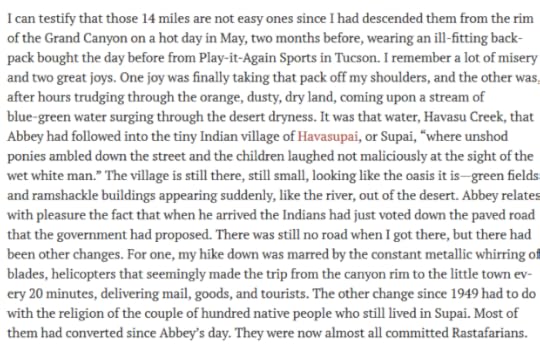

Abbey in Havasu

March 30, 2015

Lundgren’s Lounge: “Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America,” by Jill Leovy

Jill Leovy

Recent national events make it clear that W.E.B. DuBois’ famous observation, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line…” is every bit as resonant today to describe twenty-first century America as it was when first uttered, over a century ago. Ferguson, Staten Island, Cleveland, Madison… the drumbeat of places where young, unarmed black men have been killed by the police rolls on and the disconnect in the convoluted conversation between communities of color and the mostly white power structure are maddeningly unproductive, as though the dialogue is being spoken in different languages.

That is why Jill Leovy’s recent non-fiction work, Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America, is so important. As Michael Connelly is quoted on the front cover, “Everyone needs to read this book.” Perhaps more succinctly, people need to read this book who are bewildered by the black community’s reaction to the events mentioned above: after all, wasn’t Officer Darren Wilson exonerated by the grand jury investigating the death of Michael Brown?

African-American males comprise 6% of the U.S. population, yet they are 40% of the homicide victims. The vast majority of these crimes occur in our inner cities where they remain unsolved, receiving scant attention from a beleaguered and woefully underfunded section of the police force, the homicide detectives. The absence of authority and attention to these murders sends an unmistakable message to the black community that engenders an inevitable and deeply rooted distrust of the criminal justice system. This “plague of murders” is what happens when as Leovy says, “.. the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death… homicide becomes endemic.”

Leovy’s account is not a screed against the police–her focus is on a specific murder and the work of Detective John Skaggs to solve the case. Skaggs is a fascinating character: California beach bum on the weekends, yet relentless in his pursuit of what he perceives as justice while on the job. The murder victim at the center of this riveting narrative is the son of a highly respected African-American detective with the Los Angeles police. Leovy, an award-winning journalist for the Los Angles Times is as relentless as Skaggs in her attempts to get to the heart of this incredibly complex and nuanced issue. While she occasionally fails to acknowledge the inherent racism in play here, she does recognize the sociological dynamic. She writes, “Take a bunch of teenage boys from the whitest, safest suburb in America and plunk them down in a place where their friends are murdered and they are constantly attacked and threatened. Signal that no one cares, and fail to solve (the) murders. Limit their options for escape. Then see what happens.”

It is not a pretty sight. You will be maddened as you read, at the apparent indifference of the uniformed police and the absurd dysfunction of a police bureaucracy obsessed with meaningless statistics while people are being are being slaughtered on the streets. The heroes in this sobering tale are the homicide detectives–the John Skaggs and Wallace Tennelles (father of Bryant, the young man whose murder is at the heart of the story) of the world, people who see that justice, to be just, must be color-blind… and that recognition of this fact might, just might, be a starting point for a deeper conversation about the problem articulated by Prof. DuBois over a hundred years ago.

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. When he’s not skiing.]

[Bill Lundgren is a writer and blogger, also a bookseller at Longfellow Books in Portland, Maine (“A Fiercely Independent Community Bookstore”), where you can buy this book and about a million others, from booksellers who care. Bill keeps a bird named Ruby, a blind pug named Pearl, and a couple of fine bird dogs, and teaches at Southern Maine Community College. When he’s not skiing.]

March 26, 2015

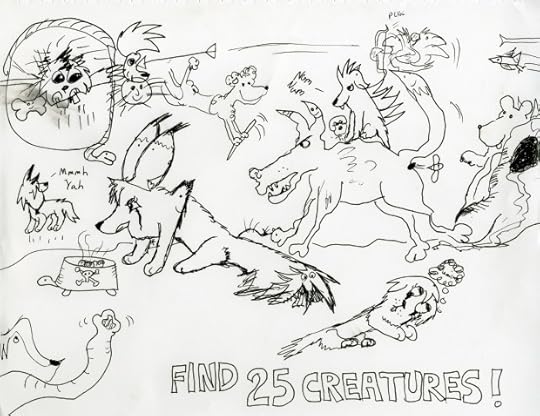

Find 25 Creatures!

Hadley, 11, drew a dog the other night. Then I drew one. Then she drew some other kind of creature. Then I drew another kind. And off we went…..once the page was too full to draw new creatures, we drew creatures within creatures. See if you can find 25. Or 30…..or more….