Cal Newport's Blog, page 53

September 8, 2013

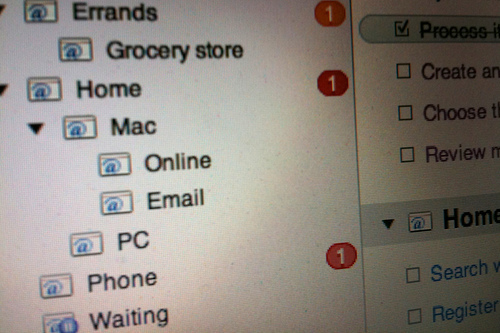

Will You Get Tenure? Replicate the Academic Promotion Process to Get More Value Out of Your Work

The Depths and the Shallows

I worry a lot about deep work (giving sustained attention to hard things that create value). As a professor, deep work is required to produce new results. Therefore, the more I do, the better.

I often envy the schedules of professional writers — like Woody Allen, Neal Stephenson, or Stephen King — who can wake-up, work deeply until they reach their cognitive limit, then rest and recharge until the next day.

The simplicity of this rhythm is satisfying. I could never emulate it, however, because, like most knowledge workers, I’m also saddled with quite a bit of shallow work (task-oriented efforts that do not create much new value). You’d be surprised, for example, how much time you spend after you write an academic paper, formatting it properly for publication (a scene they seemed to skip in A Beautiful Mind).

Most knowledge workers face this same battle between what’s needed to make an impact in the long term, and what’s needed to avoid getting fired in the short term. Professors, however, are particularly good (or, at the very least, particularly concerned) about preserving deep work in the face of mounting shallow obligations. The reason for this attention is simple: tenure.

A Referendum on Depth

During tenure review, a professor’s body of published work is put to scrutiny by a panel of experts. Their goal is to assess how much new (intellectual) value you created in your field. There’s no hacking this process (the panel contacts multiple academics from your same research niche and says: “tell us honestly — and confidentially — is this guy’s work really that impressive?”). There are no points given for the fact that you always respond to e-mails quickly or built up a lot of Twitter followers.

At the end of the review, if it’s decided you’ve made a major contribution to the world of ideas, you get a promotion. If not, you’re fired.

Most knowledge work fields, of course, don’t have the equivalent of tenure review. But an interesting thought occurred to me recently: What if they did? Imagine that after a few years a panel of outside experts in your industry was going to scrutinize the contributions you’ve made — not to your company, but to your industry — and fire you if they’re not impressed with what they find. How would this change your daily habits? My guess is that you’d spend less time checking e-mail.

Personal Tenure

I won’t suggest that you formally replicate all the elements of tenure review in your own work life, but there’s something to be said for replicating the basic idea. Every two or three years, for example, consider stepping back and assessing the actual amount of new value you’ve created in your field. If your hypothetical tenure committee is not impressed with the results, fire your current habits.

I suspect that there’s a large number of well-educated and ambitious knowledge workers out there who would come away from such a review realizing that their attention has been dedicated almost exclusively toward mastering the shallow: doing what they’re asked as quickly as possible, and occasionally suggesting new “initiatives,” like setting up social media accounts for their company, that are satisfyingly accomplishable, but also easy to replicate and not a source of new value in the world.

This is why this type of review is important. Deep work is not natural. It’s not going to be your first instinct when asking “what should I do next?” But this is also what makes it so effective when you succeed in making it a priority.

(Photo by tsmall)

#####

My friend Dan Schawbel just published his latest book: Promote Yourself. Dan is an expert at something I know very little about (and wish I knew more): making sure your skills are appreciated once you’ve put in the time to develop them. His expert take on these soft skills arguably provide a nice counterpoint to my relentless drumbeat focus on hard skills. If it sounds interesting, you can find out more on his book site…

August 28, 2013

Why Draper University Won’t Work (But Could)

School for Heroes

Every morning, the students at the Draper University School for Heroes recite an oath:

“I will promote freedom at all costs.”

“I will do everything in my power to drive, build, and pursue progress and change.”

“My brand, my network, and my reputation are paramount.”

This school was recently founded by the famed Silicon Valley venture capitalist Tim Draper (pictured above). Its goal is to produce “innovators” who do the “great things they are capable of.”

It’s also an idea that I am convinced will fail. And it’s what’s missing from this oath that underscores why.

Innovation is Fueled by Mastery

The program at the Draper University School for Heroes focuses on soft skills. There are classes in idea generation, painting, networking, and, for some reason, first aid and suturing.

There’s nothing wrong with maintaining a robust network or hearing inspirational speeches about being the change you want to see in the world. But this is not nearly enough if your goal is producing impactful innovation.

In researching my last book, I interviewed many people who ended up making a real impact on the world, including innovative biologists, agriculturists, and education entrepreneurs. The common trait they shared was expertise. They each started by putting in a lot of work to master something hard but valuable. It was this mastery that gave them the insight and ability needed to do produce real innovation.

As currently structured, Draper University focuses on young people, who, for the most part, do not yet have any expertise. Some have even dropped out of school in their eagerness to get started in their quest to do something big. Draper would applaud this boldness. I think it’s premature.

If you fire up a group of college students to go start companies and change the world the result will likely be yet another consumer-facing start-up focused on the needs of twentysomething Californian college students (to ape George Packer’s recent critique of the Valley).

By contrast…

If you want Google you need a pair of guys who were well along in Stanford’s PhD program and who were well-versed in the state of the art Information Retrieval literature.

If you want Microsoft you need a nerd who obsessively honed his programming skills and was willing to spend sleepless months mastering the opcodes of the first microprocessors.

If you want to sequence the human genome you need an entrepreneur who first spent a decade working in academia and at the NIH mastering the latest advancements in biogenetics.

And so on.

In other words, I support the vision of Tim Draper. The soft skills he teaches are important. We need to be reminded and encouraged to take risks and think big.

But I disagree with his choice of a target market. For the most part, the people most poised to really make a difference are not the eager college students currently occupying the bean bag chair-equipped lecture halls of Draper U, but instead are more likely to be found among the senior doctoral candidates and recently tenured professors at the world-class universities that happen to be within spitting distance of Draper’s San Mateo campus.

What’s missing from the oath of Draper University, in other words, is a commitment to putting in the hard long hours necessary to master the fields from which the next big innovations will surely arise. The soft skills are meaningless without something hard to back them up.

August 21, 2013

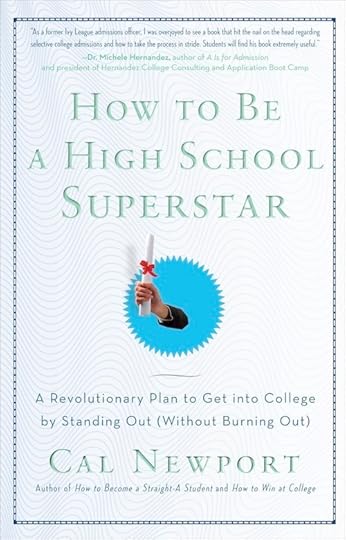

Do You Want To Succeed in College Admissions? Finish Something.

The Best Book (of Mine) You Haven’t Read

My third book, How to Be a High School Superstar, is one my favorite things that I ever wrote.

The book is best summarized as a college admissions guide written in the style of Malcolm Gladwell. Within its pages, I dive deep into the science and psychology of impressiveness and argue that it’s possible to do well in college admissions without being stressed out and overworked (see this blog post for more details).

One of the big ideas in the book is that exceptionally impressive accomplishments are rarely planned out in advance. They instead usually come from the following cycle:

the student chooses something that seems interesting,

the student follows through and completes the pursuit,

the student surveys the new opportunities this makes available, then he or she repeats step #1.

Follow this for strategy for a year (or even less!) and you’ll likely end up somewhere quite impressive (at least, by college admissions standards), without having to stress yourself out with twenty activities or attempting to become a world-class musician.

A reader recently sent me his experience following this strategy in high school. Given that it’s back to school season, I thought I’d share it (with my commentary added):

I was going to be a sophomore in high school and I wanted to write a sports blog. “Hmm,” I said to myself, “let’s write it about the New York Knicks.” To be honest, I had never been a huge Knicks fan but always wanted to explore a professional sports team in-depth.

[Note from Cal: Contrary to conventional wisdom, this student did not start by identifying an unquenchable passion. He just thought it might be interested to try blogging. He didn't even particularly like what he was blogging about. He certainly had no master plan for where it would lead.]

I started writing blog posts every day. Pretty soon, I had a decent following.

Among the community, within three months, I was quickly becoming a “go-to source” for Knicks info.

[Note from Cal: His next step was to pay his dues. People don't expect 15 year-olds to follow through on self-directed activities. When you do, good things happen...]

I emailed the Knicks media department seeing if I could get credentials to Media Day where you interview professional basketball players. They said: “Sure, just send us your Google Analytics and we’ll see if we can approve you.” Sure enough, they did.

(Little did they know I was 15 years old at the time.)

My mom drove me. It was me and a bunch of professional journalists asking these basketball players a bunch of questions. There were kids who would have died to be in my position!

Shortly thereafter, a writer from the New York Daily News mentioned me, my site, and my story in a blog post.

Even though I had a subpar GPA and a decent SAT score, I got into my top choice.

[Note from Cal: When you hear, "this kid is a credentialed sports journalist featured in the New York Daily News," your first instinct is to think he's a prodigy and a genius. But when you then learn the details of his real story -- as with most such "gee whiz" student tales -- you realize the path was more humble. He choose something interesting and followed through. He then asked, "what's next?" This isn't easy. And it requires quite a bit of confidence. But what's important is that it's not nearly as stressful as what most ambitious young people put themselves through during this process.]

August 17, 2013

Your Career is Not a Disney Movie

Believe in Your (Animated) Self

A reader recently sent me an article from The Atlantic. It was titled (quite descriptively): You Can Do Anything: Must Every Kids’ Movie Reinforce the Cult of Self-Esteem?

The writer, Luke Epplin, points out that modern animated kids films have largely fallen into a formulaic rut:

“[The protagonists are] anthropomorphized outcasts who must overcome the restrictions of their societies or even species to realize their impossible dreams.”

In these movies, explains Epplin:

“[I]t’s the naysaying authority figures who need to be enlightened about the importance of never giving up on your dreams, no matter how irrational, improbable, or disruptive to the larger community…Following one’s dreams necessarily entrails the pursuit of the extraordinary in these films. The protagonists sneer at the mundane, repetitive work performed by their unimaginative peers.”

It’s believing in one’s self, for example, that allows a fat panda to become a Kung Fu master, a to rat become an accomplished chef, and a creaky crop duster to become a world class racer — after only a bare minimum of training and essentially no experience.

The fools in these movies are those poor suckers who wasted their time practicing when all they really needed was a pep talk.

G-Rated Career Thinking

Epplin draws a connection between this narrative device and the rise of the cult of self-esteem among young children. I’m interested, however, in a different (and equally disturbing) connection.

These (literally) childish plot devices are eerily similar to the popular conversations surrounding career planning. The passion culture tells us that the key to an extraordinary life is to look deep, be true to your inner passion, and courageously ignore the naysayers as you pursue your dream.

Here’s a quote, for example, from a popular career guide:

“You see, I believe you already have everything you need inside of you. You are good enough the way you are. You’ve simply learned ideas that keep you from living up to your full potential.”

Here’s another quote, this one from one of the growing number of lifestyle design blogs:

“[D]eep down in the chambers of your heart where your personal legend lives, you know you were meant to change the world.”

It’s easy to imagine these quips coming out of the mouth of an anthropomorphized panda bear or kindly puffer fish in a Disney movie.

And this is a problem.

These similarities, once pointed out, emphasize an important and distressing reality: The ubiquitous suggestion that you must find your passion and overcome naysayers is not deep wisdom. It is, instead, the plot of a kiddie movie.

If you study real people who build remarkable lives in the real world, you find their paths are more nuanced, more complicated, and usually quite a bit more interesting. These paths tend to involve quite a bit of hard work — much of it conventional — and don’t tend to involve a lot of bold resistance to the status quo. (Society, it turns out, doesn’t care what you do for a living. It cares more about how well you do what you do.)

It’s time, in other words, for our taste in career advice to mature alongside our taste in movies.

August 14, 2013

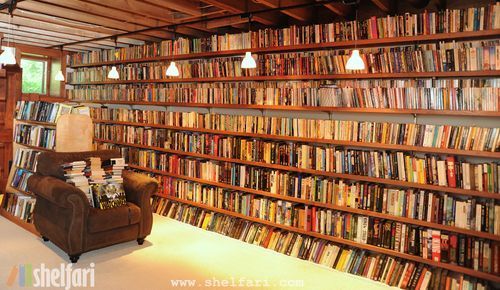

Deep Work and the Good Life

Pictured above is the cabin where journalist Michael Pollan used to write his nature-themed books before he moved to California. He built it himself.

This is a shot of the library where Neil Gaiman dreams up his confoundedly original brand of fantasy literature.

This bat-fenced Gothic mansion is the Bangor, Maine home of Stephen King. What better place to pull together his brand of dark fiction?

I’m sharing these photos because they help remind me of an important idea: deep work can be immensely fulfilling. The deep workers mentioned above recognize this reality. They built working environments that emphasize what is unique and compelling about their particular expertise, and by doing so were able to squeeze even more meaning and satisfaction out of their working hours.

This lesson is important. We should not treat deep work as just another scheduled task to check off our Allen-esque lists. It should be made, instead, the center of our efforts to lead a Good Life.

As I was thinking about this post, I faced a typical deep task in my life as a professor: I needed to break down and understand a knotty paper so I could potentially build off its results. To interact with the world of ideas at the highest level, I reminded myself, is a pretty cool way to make a living. So I left the florescence of my office and relocated to a more scenic view (above); a more fitting setting to revel in depth.

(King home photo by JHR images)

August 4, 2013

Woody Allen and the Art of Value Productivity

A Tale of Two Productivities

As a graduate student I was known for being organized. I was reminded of this a couple weeks ago when I attended a computer science conference along with many of my old lab mates.

What I also remember is that I always felt indifferent about this reputation. To be organized is a nice thing. But it didn’t take me long at MIT before I realized it’s also unrelated to what matters most: the consistent production of high value results.

We don’t often talk about this division but I think it’s crucial. There’s a lot written about task productivity (the ability to organize and execute non-skilled obligations), but much less written about value productivity (the ability to consistently produce highly-skilled, highly-valued output).

As I’ve settled more into life as a professor, I’ve been increasingly fascinated with value productivity. It’s not that task productivity lacks importance — it has saved me much stress — but I think the value variety is what will rule in an increasingly competitive knowledge economy.

It is with this fascination in mind that I spent some time recently re-watching Robert Weide’s deep diving documentary on the life and habits of Woody Allen. When it comes to value productivity, Allen is an unquestionably good place to start. He’s written and directed 44 movies in 44 years, earning 23 Academy Award nominations along the way.

By watching the documentary with an ear for work habits, I picked up the following three ideas that help explain Allen’s astonishingly high level of value productivity…

Idea #1: Don’t Break the Chain

One of Allen’s best known habits is that he writes every day for a fixed amount of time. As he explained: “If you work only three to five hours a day you become very productive. It’s the steadiness of it that counts. Getting to the typewriter every day is what makes productivity.”

The flip side of this commitment is that he feels no guilt relaxing once he hits his daily quota.

Seinfeld calls this the “don’t break the chain” strategy — and it has a large following. In the past, I’ve been skeptical of such rigidity. Allen, however, might be converting me to this point of view; at least, for certain types of work, namely non-urgent, high value projects.

Here’s why: It’s easy to convince yourself that these projects have a high priority in your life while at the same time you commit a shockingly small amount of time toward their completion. This is a recipe for self-delusion or self-despisal (when you realize how little is getting done).

Allen’s approach solves both problems.

Idea #2: Be Bold in Conception, But Pragmatic in Execution

Allen is often bold in conceiving a project. Once he starts executing, however, his focus turns to doing whatever it takes to ship a finished product on budget and on time.

“You always set out trying to make Citizen Kane,” he famously quipped. “By the time you get to the editing room, you try just not to be humiliated.”

(This reminds me a lot of the publishing process. My books are always ground breaking. Then I have to write them.)

Allen’s balance is critical because it’s easy to fall too far to one side or the other. If you just ship for the sake of shipping, for example, you’re likely to end up producing an ever-growing mountain of mediocrity. You must, in other words, push yourself to do something better. At the same time, if you become too entangled in your own hype, you’re likely to fall into perfectionism — letting years worth of opportunities pass as you ponder your masterpiece.

Idea #3: Focus on High Return Activities, Not Twitter

Early in his career, Allen identified what activities generated the highest returns, and then focused relentlessly on these behaviors to the exclusion of most other distractions.

He writes scripts, for example, freehand in a home office on yellow notepads. Once the idea begins to gel he types a polished version on an Olympia SM-3 manual typewriter — the same machine he bought as a teenager when he first began writing gag lines for newspaper columnists.

By stripping down his work hours to the core elements, and removing from his life the often insidious question of “what should I do next?”, he’s able to extract a huge amount of value from the limited hours he spends each day writing.

But what about social media you ask? Certainly an entertainment personality needs a following online! Allen (and his 23 Academy Award nominations) disagrees. Forget Twitter, he’s never owned a computer.

July 28, 2013

Lessons from Rosie O’Donnell’s Ten Year Big Break

O’Donnell’s Ten Year Big Break

Last month, Rosie O’Donnell appeared on Here’s The Thing, Alec Baldwin’s NPR interview show.

The episode, if heard casually, gives the impression that her break was rapid and inevitable. As a high school senior, we learn, she wrote comedy skits for a school variety show. A local comedy club owner liked the skits and invited O’Donnell to perform a set. She killed.

At this point, it was clear that she would become a comedian. Her break came later when Lorne Michaels and Brandon Tartikoff (former NBC chief) happened to hear her perform at a club where they had come to audition Dana Carvey.

Tartikoff came up to O’Donnell after the show and said simply: “Hi. I want you to call this number at NBC tomorrow. We have a job for you.”

Television, then movies, then her talk show — it all fell into place after that key moment.

This is a classic big break. But if you listen closer to the episode it becomes clear that it was not out of the blue. While telling this story, O’Donnell, as an aside, clarified the timeline of that fateful night by noting: “[Remember that at this point] I had had a decade under my belt of doing standup, right?”

O’Donnell’s big break, in other words, was ten years in the making…

Competing Big Break Theories

If you study people with remarkable careers they often tell stories similar to O’Donnell: they begin with a long period of anonymous striving followed by a break then rapid ascent (see also, Martin and Schwarzenegger).

There are two interpretations of this trend…

The first interpretation says that lucky breaks, by definition, are low probability events. Therefore, you have to open yourself up to opportunity again and again and again before you can expect one of these low probability events to finally occur. It took O’Donnell a decade to break out, according to this theory, because the probability that Lorne Michaels and Brandon Tartikoff show up at your show is really low.

The second interpretation draws from career capital theory. It tells us that lucky breaks are essentially impossible until after you have developed a rare and valuable skill. At this point, breaks actually become quite probable, so long as you are doing the right things to demonstrate your skill. This theory tells us that it took O’Donnell a decade to break out because this is how long it takes to develop comedy chops. The fact that Michaels and Tartikoff wandered into her show is inconsequential. Once she was excellent, some event like that was bound to happen sooner or later.

The problem with the first interpretations is that it leads people to bounce from thing to thing, always hoping that something unexpectedly hits big, never taking the time to produce real value.

The second interpretation tells us to instead focus on whether or not we have crossed the break threshold — the point at which you are so good you can’t be ignored and a big break has become possible. It’s really hard to cross this threshold in most fields, and if you’re not explicitly pursuing this goal you’ll likely end up in a purgatory of professional but unremarkable skill, playing half-empty clubs, hoping that the right executive happens to walk through the door.

#####

An Administrative Aside: From what I understand, Google Reader no longer exists. This probably explains why my RSS subscriber count recently dropped by 20,000! If you’re an RSS subscriber, I’ve heard good things about Feedly. (My same RSS feed will work, you just need a new reader.) Also, I’m in the middle of a site redesign that will finish up in August/September. As part of this redesign, I’m launching an e-mail list that will allow you to receive my posts, plus some extra content, right in your inbox. Stay tuned for more details…

July 2, 2013

Why Did Most of Dartmouth’s Valedictorians Become Investment Bankers and Consultants? The Need for a Deeper Vocabulary of Career Aspiration

The Brain Drain

My alma mater, Dartmouth College, graduated five (!) valedictorians this year.

Dartmouth, of course, is not alone in sending a disproportionate number of its best and brightest to these narrow sectors. In recent years, to name an oft-cited example, Princeton sent 36% of its students to finance jobs while Harvard sent 17%.

There are many reasons proposed for this brain drain (whether or not this is really a “drain” is a different debate, though I tend to agree it is), including: prestige, money, the need to pass a new competitive admissions process to signal value, and psychologically-astute recruiting tactics.

I’m particularly interested, however, in an explanation offered by David Brooks in a recent column:

“Many of these students seem to have a blinkered view of their options.”

According to Brooks, elite students assume their choices are limited to: (a) making lots of money in finance and consulting, or (b) saving the world by working for a boots-on-the-ground non-profit. [Stanford students, Brooks notes, get an extra option less popular on the East Coast: (c) starting a tech company.]

This rings true.

A Stunted Career Vocabulary

Something I noticed time and again when out talking about SO GOOD is that the current generation of college students has a stunted vocabulary when it comes to discussing career aspirations.

I’m not exactly sure why, though I hypothesize it’s some combination of the character-crushing competitive college admissions process (which most students don’t understand) and the dulling effect of the “follow your passion” culture. When college graduation looms, these students realize that they lack the mental models needed to develop a sophisticated vision of the role work can play in a life well-lived. So they fall back on simplistic heuristics.

What we need is more career conversations, started much earlier, handled with significantly more subtlety and intelligence than most 19 year-olds, or the career advice industry that caters to them, seem willing to pursue.

A Deeper Career Vocabulary

In an effort to begin a transition toward a richer vocabulary of career aspirations, I’ve listed below three issues relevant to career choice that any ambitious college student, confused about life after graduation, should spend more time trying to understand…

The Value of Craftsmanship. There’s a deep sense of satisfaction in the process of mastering a craft that produces things that the world values. There’s an even deeper satisfaction in subsequently applying this craft and receiving recognition for your competence. For millennia, human culture has understood and revered this value. Many different career paths can provide this return — if you know what you’re looking for.

The Importance of Lifestyle. What traits define, to you, a good life? Autonomy? Time affluence? Mobility and adventure? Connection? Influence? Impact? Students tend to place too much importance on the specifics of a job, as if there was a specific knowledge work pursuit hardwired in their genes. It is instead the general traits of their lifestyle that tend to bring people satisfaction — not specific jobs. How deeply do you understand what general traits resonate with you? This understanding brings great clarity to your path through the working world.

A Personal Ethic. Identifying your core values is important. But equally important is translating these values into an actionable ethic. As Brooks mentions in the column I cited earlier, too many students seem stuck with a watered down, college admission-style model of ethics, where doing volunteer work is sufficient to label your life as moral. Ethics run deeper. If, for example, you’re talented enough to graduate at the top of an Ivy League class, you need to ask: What is my responsibility to the world? What legacy do I want to leave behind? This doesn’t mean you must aspire to become the next Paul Farmer. On the other hand, it might mean that helping a hedge fund make a small number of wealthy people slightly more wealthy does not make the cut. (See Clayton Christensen’s recent book for interesting thoughts on this topic.)

To summarize, what you do for a living is important. When you face this decision for the first (though certainly not last) time, you need to approach it with more than a slogan and a handful of cliches. This is a topic that deserves a deeper and more nuanced conversation.

June 26, 2013

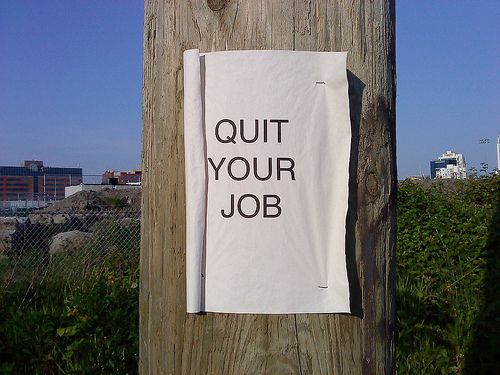

The Courage Crutch: A Remarkable Life Requires You to Overcome Mediocrity, Not Fear

The Cult of Courage

The rhetoric surrounding career advice is saturated with calls for “courage.” Here are a few representative quotes I grabbed at random from the web:

“[S]ensational and successful entrepreneurs…had the courage to pursue what makes their heart sing.”

“As we move out of our comfort zones towards either accomplishing new things or approaching new levels of greatness, it’s normal to lack courage…”

“A great deal of talent is lost to the world for want of a little courage.”

“In our day-to-day lives, the virtue of courage doesn’t receive much attention…Instead of setting your own goals, making plans to achieve them, and going after them with gusto, you play it safe. Keep working at the stable job, even though it doesn’t fulfill you.”

The storyline told by such quotes is simple: You know what career decisions would leave you happy and fulfilled, but “society” and “your family” are fearful, dull, stupid, and devoid of useful wisdom, and will therefore try to scare you out of following this good path. You must, therefore, build the courage to overcome their fear-mongering so you can live happily ever after.

The influence of this narrative, and the broader courage culture (as I named it in SO GOOD) that supports it, provides me a ceaseless source of annoyance. Given that it’s graduation season, and the topic of career happiness is therefore relevant, I thought I’d offer a few thoughts about why this trope irks me so much, and why you should treat it with caution.

Three Problems with the Courage Culture

Here are my main issues with the ideas promoted by the courage culture…

First, it’s narcissistic. The courage culture sets up a narrative where you are the noble warrior resisting overwhelming efforts to coerce you into conformity. It supports an almost conspiratorial worldview where unnamed forces are massed against your efforts to do something great.

The reality, of course, is that you’re not Frodo, and there’s no occupational Sauron to evade. No one cares what you do for a living. They care only about what tangible value you offer the world.

Second, remarkable accomplishments are hard, not scary. Almost without exception, building a remarkable career requires that you become remarkably good at something valuable. This requires time and is hard. But it’s not particularly scary. By the time most people are skilled enough to do something remarkable, the decision can seem more obvious than fear-inducing.

Consider, for example, the founding of Apple Computer. Steve Jobs took the plunge into starting the company because Paul Terrell placed a six-digit order for Wozniak’s remarkable Apple 1. When someone offers you hundreds of thousands of dollars for a product you designed in your spare time, you don’t need courage to start a company, you need, instead, the will to bust your ass (which is exactly what Jobs did).

Stephen King provides another good example. He wrote in his spare time since he was a boy. He didn’t quite his job to write full time, however, until after he sold the paperback rights to Carrie for $400,000. To quit a job that was paying him one-twentieth of that amount was an act of reasonable accounting, not courage.

Third, it’s insulting to people who know more than you about life. The idea that society, and, more specifically, your parents and community, are steering you toward unhappiness because of their stupidity and irrational fear of uncertainty, discounts the fact that their advice is drawn from many years of experience. They’ve lived longer than you. They’ve been through different careers. They’ve watched friends try different things. (If you’re an echo-boomer, they’ve probably watched friends try wild, outlandish things.) They have, in other words, many hard won data points to pull from when they offer their thoughts.

It’s possible, in other words, that your parents are discouraging you from quitting your job to start a blog business because it’s a bad idea — not because they’re myopic and meek.

Bottom Line

The courage culture paints a tempting picture of how people end up with remarkable lives. It tells a story where you’re the main character, fighting evil forces, and ultimately triumphing after a brief but intense battle.

The reality is decidedly less exciting. Remarkable careers require that you become remarkably good. This takes time. But not necessarily a string of defiant rejections of some mysterious status quo.

(The brevity of the courage culture’s recommendations are a big part of their appeal. It takes a few weeks of courage to quit your stable job to pursue something bold. Building a real skill, by contrast, takes a long time and is much less fun. We shouldn’t be surprised that people prefer the abridged version of this particular story.)

For most people who aspire to a passionate working life, in other words, the key is not overcoming fear, but instead overcoming mediocrity.

(Photo by Kevin Krebs)

June 17, 2013

An Animated Argument Against Passion

A reader recently sent me the following note:

I was a believer in “finding your passion” until I read your book. It has freed me from the frustration and impatience bred from the continuous quest to “find the perfect job.”

Enlightened, I made an animation to share the idea with my friends.

This animated short is embedded above. I thought those of you who read SO GOOD would enjoy it.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers