Cal Newport's Blog, page 54

June 5, 2013

Hacking Deep Work with Project Step Labels

Hacking Depth

The equation is simple: the more deep work you do the more new value you create. And creating value, of course, is the key to a remarkable life.

Acting on this equation, however, can be surprisingly difficult.

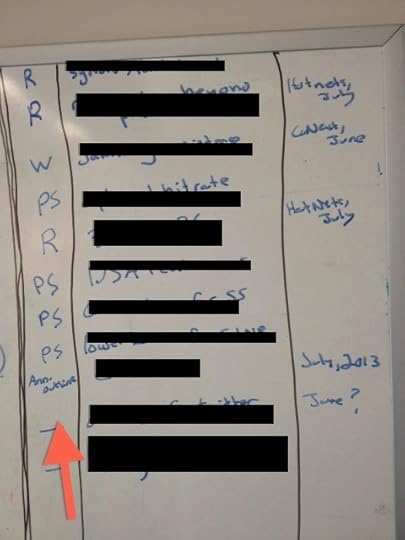

Here’s a simple hack (that came out of my recent anti-planning stretch) that has helped me rack up more deep work toward my computer science research: I append my list of active projects with a code indicating the next step I’m trying to reach (see the left column in the image above).

Having this extra column greatly simplifies my transition into a deep work mode, as my goal for these sessions is now simple: try to advance to the next steps on these projects.

This hack also works, in part, because specificity is crucial for deep work (your mind needs a crystal clear target before it will marshal the resources needed to go deep). It also works because the simple positive feedback (updating my board every time I move to the next step of a project) taps into our brain’s habit circuitry (c.f., Duhigg).

When it comes to deep work, there’s no magic bullet that will make it effortless. This work is hard. But hacks of this type can help keep these efforts from sliding toward impossible.

June 1, 2013

The Deliberate Rise of Stephen King

On Reading On Writing

Every few years I re-read On Writing, Stephen King’s professional memoir. It helps me reorient to the reality of becoming better at creative endeavors.

Here’s King, talking about his initial efforts to publish his short stories in magazines:

“When I got my rejection slip…I pounded a nail into the wall above the Webcor [phonograph]…and poked [the rejection slip] onto to the nail…By the time I was fourteen (and shaving twice a week whether I needed to or not) the nail in my wall would no longer support the weight of the rejection slips impaled upon it. I replaced the nail with a spike and went on writing. By the time I was sixteen I’d begun to get rejection slips with handwritten notes a little more encouraging.”

It would be another ten years before King sold his first novel, Carrie.

The obvious lesson of this story is that King wrote a lot before he became good. The visual of rejection slips filling a spike is vivid.

But there are two other important elements lurking, uncovered only with a deeper reading of On Writing.

First, King didn’t just write, he tried to get people to pay for his writing, by submitting it to magazines. The nice thing about money (as I elaborate in SO GOOD) is that people don’t like to give it up. Therefore, when you ask people to give you money in exchange for your product, you’re going to get brutally honest feedback.

Second, King was careful to always aim above, but just barely above, his current skill level. His first published story was in a fanzine — the 1960′s version of a blog. He moved from fanzines to second-tier mens magazines like Cavalier and Dude. After he cracked that market he moved on to top-tier mens magazines and top-tier fantasy and science fiction publications. Only once he could consistently hit those targets did he succeed in selling his first novel to Doubleday.

Let’s step back and summarize these key points of King’s training: lots of practice, driven by honest feedback and challenges just beyond his current skill level.

Sound familiar?

King’s rise to writing fame is a perfect case study of deliberate practice in action.

(Photo by snck)

May 22, 2013

Controlling Your Schedule with Deadline Buffers

A Hard Week

Last week was hard. Four large deadlines landed within a four day period. The result was a week (and weekend) where I was forced to violate my fixed-schedule productivity boundaries.

I get upset when I violate these boundaries, so, as I do, I conducted a post-mortem on my schedule to find out what happened.

The high-level explanation was clear: bad luck. I originally had two big deadlines on my calendar, each separated by a week. But then two unfortunate things happened in rapid succession:

One of my two big deadlines was shifted to coincide with the second big deadline. Because I was working with collaborators, I couldn’t just ignore the shift. The new deadline would become the real deadline.

The other issue was due to shadow commitments – work obligations you accept before you know the specific dates the work will be due. I had made two such commitments months earlier. Not long ago, however, their due dates were announced, and they both fell square within this brutal week.

The easy conclusion from this post-mortem is that sometimes you have a hard week. Make sure you recharge afterward and then move on.

This is a valid conclusion And I took it to heart. But it’s not complete…

The Deadline Banner

As I dug deeper through the forensic detritus of this brutal week I noticed that I could have made it less brutal. As deadlines popped up or shifted on my schedule, I dutifully updated them on my calendar. But in doing so, I didn’t appreciate the monumental work pile-up these shifts were creating. If I had noticed this, I could have invoked some emergency measures earlier to lessen the load.

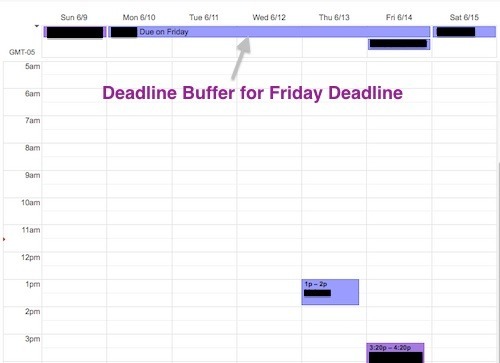

In response to this revelation I am now toying with a simple tweak to how I use my calendar: the deadline buffer.

The idea is simple…

Any serious deadline should not exist on your calendar just as a note on a single day. It should instead by an event that spans the entire week preceding the actual deadline. (In Google Calendar, I do this by making it an “all day” event that lasts the full duration; e.g., as in the screenshot at the top of this post.)

The motivation behind this hack is to eliminate the possibility for pile-ups to happen without your knowledge. If you buffer each deadline with a week-long event, any overlap will become immediately apparent.

As a bonus, this approach also helps you keep these key pre-deadline weeks clear of excessive meetings. It’s easy, for example, to agree to a non-urgent interview months in the future. But when you see that this date has a deadline buffer in place, you become more likely to say, “actually, let’s schedule this for the week after…that week is going to be a little tight.”

This is the type of prescient scheduling you’ll appreciate when the deadline looms and you see before you a delightfully light schedule.

In the spirit of anti-planning, I don’t know how well this will work, but it’s worth some experimentation.

May 7, 2013

Do More By Planning Less: The Power of the Anti-Plan

Seeking Full Capacity

Since becoming a professor, my productivity (as measured by original publications in quality venues) has improved.

I’m happy about this fact.

But I’m also convinced that I’m still leaving capacity on the table. As my expertise in my area grows, I’m reaching a point where I have more ideas per year than I have time to publish (which can be frustrating). If I could increase my deep to shallow work ratio just a little more, I could, I think, close that gap.

Accomplishing this goal, however, has proved difficult.

According to my Monthly Plan archives, since September 2012 I’ve launched at least six different plans aimed at increasing my research output, with the goal of closing this final gap.

None made a major impact.

With this in mind, I’m taking advantage of the beginning of summer to try, as I like to do every now and again, the most radical of productivity plans — no plan at all.

Anti-Planning

I’m a believer in something I call anti-planning.

A normal plan requires you to figure out in advance when and how you’re going to accomplish important projects.

An anti-plan has you to throw out all such rules and just dive in, adapting, the best you can, to your circumstances. It requests only that you keep a record of your experience, capturing, for later review, your thoughts, triumphs, and frustrations.

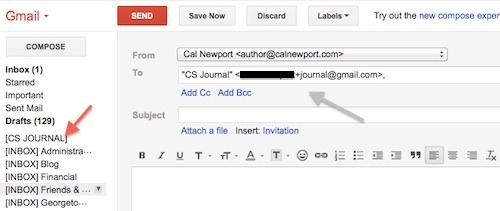

(For this purpose, I like to keep a gournal — my word for an electronic journal based on automatically filtering Gmail messages, sent to a special address, into a journal label. See the screenshot above for my setup.)

The Anti-Plan Theory

The theory behind anti-planning is that it exposes you to a much wider swath of the productivity plan landscape. Your journal will keep you updated on how well you’re doing, which provides the selective pressure needed to drive you toward some novel approaches to getting more depth out of your working habits.

People sometimes worry that anti-planning will tank their productivity. The reality is usually the opposite: the flexibility and constant self-reflection tends to increase the rate at which you produce valuable output.

For these same reasons, however, anti-planning can be draining (all that reflection and decision making reduces willpower). So I usually only last a month or two before falling back onto a more structured set of rules.

The key, however, is that the system I end up after anti-planning is often more effective than where I was before.

Bottom Line

I’ve only recently begun my most recent bout of anti-planning, so I don’t yet have new grand conclusions. But even the initial reflections now trickling in are proving quite interesting (I’m starting to realize, for example, that deep work is deeply cyclical, and not something that can happen every day of every week).

In the meantime, if you’re frustrated with the effectiveness of your productivity plans, spend some time without one, and see what bubbles to the surface.

April 24, 2013

Louis C. K. on Career Capital

The Power of Diligence

The comedian Louis C. K. lives a remarkable life. How did he make that happen? Here’s an interesting quote from a recent New York Times interview:

There’s people that say: “It’s not fair. You have all that stuff.” I wasn’t born with it. It was a horrible process to get to this. It took me my whole life. If you’re new at this — and by “new at it,” I mean 15 years in, or even 20 — you’re just starting to get traction. Young musicians believe they should be able to throw a band together and be famous, and anything that’s in their way is unfair and evil. What are you, in your 20s, you picked up a guitar? Give it a minute.

Notice his use of the phrase “horrible process” in describing his rise. This is exactly what is wrong with telling people: “If you do what you love, you’ll never work a day in your life” — you’re providing them a flawed description of reality.

Careers you love require a lot of work. Sometimes even “horrible” work.

You can’t escape the necessity of career capital…

(Hat tip: 99u)

April 10, 2013

In Choosing a Job: Don’t Ask “What Are You Good At?”, Ask Instead “What Are You Willing to Get Good At?”

I recently received the following note from a career counselor:

I regularly counsel students on their career paths and I was having a hard time giving a student guidance today without referencing passion. ‘What are you good at?”’ I asked instead, and she replied that she didn’t know. She doesn’t know because she hasn’t tried enough things.

I like that this counselor is thinking critically about passion. I didn’t, however, agree with her alternative suggestion.

Asking “what are you good at?”, in my opinion, can be essentially the same as asking, “what is your passion?”

In both cases, you’re placing the source of career satisfaction in matching your job to an intrinsic trait.

And this is dangerous.

As readers of SO GOOD know, career satisfaction almost always follows: (a) building up a rare and valuable skill; then (b) using this skill as leverage to take control of your working life.

If you lead a student believe that making the right job choice is what matters for career happiness (whether you’re choosing based on “passion” or identifying “what you’re good at”), you’re setting them up for confusion when they don’t feel immediate and continuous love for their work.

My advice to a student in the above situation is the following:

Pick something that you wouldn’t mind investing years in mastering. If you already have some skills, then it might make sense (though is by no means necessary) to start there, as you already have a head start on mastery, but you should still expect years of deliberate improvement before deep passion can blossom for your work.

The key thing, in other words, is to direct expectations away from match theory — which says passion depends primarily on making the right job choice — and toward career capital theory — which says passion will grow along with your skill.

April 8, 2013

Deliberately Experimenting with Deliberate Practice — Looking for Subjects to Test My Advice

The Deliberate Practice Pilot Program

I’m fascinated by deliberate practice.

I’m convinced this advanced practice philosophy can help knowledge workers rapidly pick up skills that will make them invaluable and provide control over their career. It is, as I’ve argued here, in my last book, and in the Wall Street Journal, perhaps one of your most effective tools for building a working life you love.

But it’s also really hard to figure out how to adapt these ideas to the world of knowledge work.

I decided a good way to proceed with my investigation of this topic would be to: (1) take my best shot at distilling what I know into a formal system; then (2) recruit a group of people, from a variety of different knowledge work careers, to try out my recommendations and report back what they experienced.

This is exactly what I’m going to do.

Over the past few months, I’ve worked extensively with Scott Young (a master of rapid learning), to create a four week pilot program that walks you, step-by-step, through our best understanding of how to identify key skills and then apply deliberate practice techniques to dominate them in a small amount of time.

Now we want to recruit an (extremely limited) group of participants to give this pilot course a try and tell us how it went. In other words, I want real people, in a variety of real jobs, to kick the tires on these ideas Scott and I have been writing about for so long.

Learn More About This Experiment

I don’t want to clog Study Hacks with tons of logistical posts about the experiment — more details, how to sign-up, etc. — so I created a separate e-mail list for this purpose. If you’re interested in learning more about this pilot program click the link below to sign-up for the list.

This will be the only place where you can hear more details and receive information about the first-come-first-served sign-up that will likely happen as soon as next week.

Click here to sign-up to learn more…

And now back to our regularly scheduled programming…

April 3, 2013

You Can Be Busy or Remarkable — But Not Both

The Remarkably Relaxed

Terence Tao is one of the world’s best mathematicians. He won a Fields Medal when he was 31. He is, we can agree, remarkable.

He is not, however, busy.

I should be careful about definitions. By “busy,” I mean a schedule packed with non-optional professional responsibilities.

My evidence that Tao is not overwhelmed by such obligations is the time he spends on non-obligatory, non-time sensitive hobbies. In particular, his blog.

Since the new year, he’s written nine long posts, full of mathematical equations and fun titles, like “Matrix identities as derivatives of determinant identities.” His most recent post is 3700 words long! And that’s a normal length.

As a professor who also blogs, I know that posts are something you do only when you have down time. I conjecture, therefore, that Tao’s large volume of posting implies he enjoys a large amount of down time in his professional life.

Here’s why you should care: Tao’s downtime is not an aberration — a quirk of a quirky prodigy — it is instead, I argue, essential to his success.

The Phases of Deep Work

Deep work is phasic.

Put another way, to ape Rushkoff, we’re not computer processors. We can’t be expected to accomplish any job any time we have the available cycles. There are rhythms to our psychology. Certain times of the day, week, month, and even year (e.g., the professor I discussed in my last post) are better suited for deep work than other times.

To respect this reality, you must leave sufficient time in your schedule to handle the intense bursts of such work when they occur. This requires that you constrain the other obligations in your life — perhaps by being reluctant to agree to things or start projects, or by ruthlessly batching and streamlining your regular obligations.

When it’s time to work deeply, this approach leaves you the schedule space necessary to immerse.

When you’ve shifted temporarily out of deep work mode, however, this approach leaves you with down time.

This is why people who do remarkable things can seem remarkably under-committed — it’s a side-effect of the scheduling philosophy necessary to accommodate depth.

Returning to Tao’s blog, the specific dates of his posts support my theory. As mentioned, he posted nine long posts since the New Year. On closer inspection, it turns out that most of the posts occurred in a single month: February.

We can imagine that this month was a down cycle between two periods of more intense thinking.

If my theory is true — and I don’t know that it is — its implication is striking: busyness stymies accomplishment.

If you’re looking for the next Tao, in other words, ignore the guy checking e-mail while running to his next meeting, and look instead towards the quiet fellow, staring off at the clouds, trying to figure out what to do with his afternoon.

(Photo by The Other Dan)

March 24, 2013

How to Write Six Important Papers a Year without Breaking a Sweat: The Deep Immersion Approach to Deep Work

The Productive Professor

I’m fascinated by people who produce a large volume of valuable output. Motivated by this interest, I recently setup a conversation with a hot shot young professor who rose quickly in his field.

I asked him about his work habits.

Though his answer was detailed — he had obviously put great thought into these issues — there was one strategy that caught my attention: he confines his deep work to long, uninterrupted bursts.

On small time scales, this means each day is either completely dedicated to a single deep work task, or is left open to deal with all the e-mail and meetings and revisions that also define academic life.

If he’s going to write a paper, for example, he puts aside two days, and does nothing else, emerging from his immersion with a completed first draft.

If he’s going to instead deal with requests and logistics, he’ll spend the whole day doing so.

On longer time scales, his schedule echoes this immersion strategy. He teaches all three of his courses during the fall. He can, therefore, dedicate the entire semester to two main goals: teaching his courses and conceiving/discussing potential research ideas (the teaching often stimulates new ideas as it forces him to review the key ideas and techniques in his field).

Then, in the spring and summer that follow, he attacks his new research projects with the burst strategy mentioned above, turning out 1 – 2 papers every 2 months. (He aims for — and achieves — around 6 major papers a year.)

Notice, this immersion approach to deep work is different than the more common approach of integrating a couple hours of deep work into most days of your schedule, which we can call the chain approach, in honor of Seinfeld’s “don’t break the chain” advice (which I have previously cast some doubt on in the context of writing).

There are two reasons why deep immersion might work better than chaining:

It reduces overhead. When you put aside only a couple hours to go deep on a problem, you lose a fair fraction of this time to remembering where you left off and getting your mind ready to concentrate. It’s also easy, when the required time is short, to fall into the least minimal progress trap, where you do just enough thinking that you can avoid breaking your deep work chain, but end up making little real progress. When you focus on a specific deep work goal for 10 – 15 hours, on the other hand, you pay the overhead cost just once, and it’s impossible to get away with minimal progress. In other words, two days immersed in deep work might produce more results than two months of scheduling an hour a day for such efforts.

It better matches our rhythms. There’s an increasing understanding that the human body works in cycles. Some parts of the week/month/year are better for certain types of work than others. This professor’s approach of spending the fall thinking and discussing ideas, and then the spring and summer actually executing, probably yields better results than trying to mix everything together throughout the whole year. During the fall, he rests the part of his mind required to tease out and write up results. During the spring and summer he rests the part of his mind responsible for having original thoughts and making new connections. (See Douglas Rushkoff’s recent writing for more on these ideas).

I’m intrigued by the deep immersion approach to deep work mainly because I don’t usually apply it, but tend to generate more results when I do. I’m also intrigued by its ancillary consequences. If immersion is optimal for deep work, for example, do weekly research meetings make sense? When you check in weekly on a long term project, it’s easy to fall into a minimal progress trap and watch whole semesters pass with little results. What if, instead, weekly meetings were replaced with occasionally taking a couple days to do nothing but try to make real progress on the problem? Even doing this just a few times a semester might produce better results than checking in every week.

I don’t know the answers here, but the implications are interesting enough to keep the immersion strategy on my productivity radar.

(Photo by moriza)

March 13, 2013

Prioritizing Deep Thought in a Distracted World: A Case Study

A Deep Day

A Deep Day

I’m a big supporter of deep work. People often ask, however, how to fit this type of persistent concentration into a fractured knowledge work schedule.

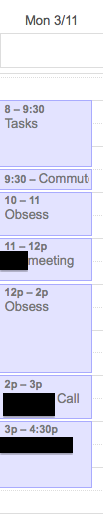

To demonstrate my personal answer, I took a snapshot of my calendar from Monday (see the image to the right).

At 9:30, I began my commute, having already tackled enough small logistics to clear my head and allow me to start obsessing on a problem I’m trying to solve (I love thinking in the car). Once I arrived on campus at 10:00, I continued to obsess about this problem until an 11:00 meeting. I then had 2 more hours to obsess. At 2:00, I had another call. Then at 3:00, now mentally exhausted, I turned to a less cognitively demanding logistical task that I’m chipping away at, bit by bit, with the goal of avoiding a schedule-busting scramble the day before the deadline.

(I should note that I teach on Tuesday and Thursday, and, accordingly, devote those full days to class related work — which is why you don’t see such tasks on the sample Monday shown here.)

Here’s the take-away message: On non-teaching days I start with the assumption that the full day will be dedicated to thinking deeply on the projects that will best increase my career capital. I then (only reluctantly) squeeze in the other stuff that simply cannot be ignored. Because I assume the day is mainly about deep work, I tend to ruthlessly batch this extra stuff and push it toward the borders of my day, where it will have a minimal effect on what matters.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers