Cal Newport's Blog, page 56

November 30, 2012

Einstein’s Rubber Ball

Detecting Deep Work

An interesting nugget from Robert Greene’s new book, Mastery: when Einstein was working on the theory of relativity, he held a rubber ball that he would squeeze when straining his mind to grapple with a particularly hard piece of the theory.

Elsewhere in the book, Greene talks about Einstein’s lifelong commitment to the violin as a tool with which he trained himself to focus. (This might be from Daniel Coyle’s Talent Code; I’m reading both simultaneously and often confuse the two)

These are tantalizing hints supporting my hypothesis that the ability to think deeply and produce real value is something that requires technique and practice. They’re also another reason why I get annoyed when people begin and end a discussion on making an impact with a dumbly simple slogan like “follow your passion!”

November 27, 2012

Some Notes on Deep Working

Diving into Deep Work

Last week I introduced the deep work philosophy — an approach to knowledge work that (in theory) increases the quality and quantity of your output. Since then, I’ve put the philosophy to the test in a mini-experiment. Starting last Saturday, I’ve dedicated roughly 1 hour of my day to deep work on a specific proof that’s been on my queue for a while.

This is a small scale experiment. My goal is to develop a preliminary understanding of how my deep work philosophy translates to practice.

Here are my observations so far…

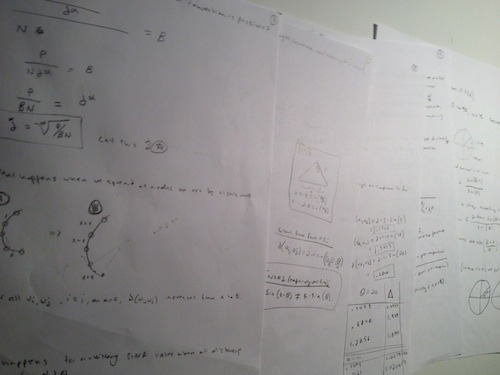

I was surprised by the amount of output produced in a small amount of time. The image above shows the notes produced so far by my experiment. These notes capture an essentially complete proof for the problem I was tackling.

Deep work definitely induced the deliberate practice of new concepts. To work out the proof notes above I had to re-learn a bunch of geometry that I hadn’t touched since high school. My tendency in these situations is to look for a theorem somewhere that proves exactly what I need, and, failing that, ask someone for the answer. The deep work mindset, however, inspired me to actually go to first principles and prove the properties I needed from scratch. I now know a little more about geometric proofs than I did four days ago.

It helps to explain things out loud. My mind, like most minds, resists the energy demands of concentrating deeply on something complicated. If I explained what I was working on out loud, however, it helped keep me focused. Yesterday, for example, I gave Max a mini-lecture on the derivatives of trigonometric functions. He responded, naturally, by crying. But I still found it useful.

Clarity is crucial. The problem I was working on this week didn’t come out of nowhere. Over the path month, I dedicated a dozen hours toward learning the main results in the relevant model. Since then I’ve been discussing these ideas with a specialist. By the time I started deep work on this particular result I had confidence that the problem was useful and had a good general strategy for solving it. Without this clarity, mustering the resources for deep work would have been harder. (A couple years ago, I wrote an article for Ramit Sethi’s blog about this idea that “just get started’ is bad advice.)

I need a stronger ritual. I was working at home without much transition into this deep work. I had the feeling that I wasn’t 100% committed to what I was working on, which probably blunted my effectiveness some. I’m working on the details of my ritual.

I assume I’ll get better with practice. There were many moments in this experiment where I felt strain and still persisted (the key to optimal quality and improvement). But I also felt like this strain was of a lightweight variety (at least, as compared to what’s possible in academic theory). With practice, I think I’ll be able to tackle increasingly complex mental puzzles — which inspires me to maintain this practice much like a runner maintains a running habit to build mileage.

November 21, 2012

Knowledge Workers are Bad at Working (and Here’s What to Do About It…)

An Inconvenient Observation

Knowledge workers are bad at working.

I say this because unlike every other skilled labor class in the history of skilled labor, we lack a culture of systematic improvement.

If you’re a professional chess player, you’ll spend thousands of hours dissecting the games of better players.

If you’re a promising young violin player, you’ll attend programs like Meadowmount’s brutal 7-week crash course, where you’ll learn how to wring every last drop of value from your practicing.

If you’re a veteran knowledge worker, you’ll spend most of your day answering e-mail.

As I’ve argued here in my new book, this represents a huge opportunity for knowledge workers. If you can adopt a culture of systematic improvement, similar to what’s common in other skilled fields, you can potentially accelerate your career far beyond your inbox-dwelling, discomfort-avoiding peers (and cultivate passion for your livelihood in the process).

But how do you adopt this approach in your specific job? This is the most common question I’m asked in response to this idea.

In this post, I want to propose a (tentative) answer…

Deep Work (v.1)

Knowledge workers dedicate too much time to shallow work — tasks that almost anyone, with a minimum of training, could accomplish (e-mail replies, logistical planning, tinkering with social media, and so on). This work is attractive because it’s easy, which makes use feel productive, and it’s rich in personal interaction, which we enjoy (there’s something oddly compelling in responding to a question; even if the topic is unimportant).

But this type of work is ultimately empty. We cannot find real satisfaction in efforts that are easily replicatable, nor can we expect such efforts to be the foundation of a remarkable career.

With this in mind, I argue that we need to spend more time engaged in deep work — cognitively demanding activities that leverage our training to generate rare and valuable results, and that push our abilities to continually improve.

Deep work, if made the centerpiece of your knowledge work schedule, generates three key benefits:

Continuous improvement of the value of your work output.

An increase in the total quantity of valuable output you produce.

Deeper satisfaction (aka., “passion”) for your work.

A working life dedicated to deep work, in other words, is a working life well-lived (a point I argue in detail in Rules 1 and 2 of my book). The question, therefore, is how to integrate deep work into your specific job.

Below I describe four steps for accomplishing this goal in almost any knowledge work profession…

Step #1: Prepare

Deep work is energy intensive. Our brains are stingy when it comes to expending energy, so you shouldn’t expect to casually switch over to a deep work mindset. It helps to instead cultivate a ritual that transitions you from normal shallow work to the deep variety.

This strategy works because it’s easier to convince your mind to do the first step of a simple ritual than to dive straight into intense contemplation. But once a ritual is begun, you’ve engaged your habit circuitry, and can expect to come out on the other side ready to focus.

In my own job as an academic theoretician, for example, this ritual might involve: shutting down my computer, shutting down my overhead lights (leaving on only my desk lamp), brewing a cup of coffee, and putting a “do not disturb” sign on my door.

Step #2: Clarify

Deep work requires a clear image of the outcome you’re seeking and a clear understanding of why it’s valuable. A hazy goal is not enough to sustain your concentration at the needed levels.

Be specific about what success will look like and why that success is important. Keep in mind that it can take a surprising amount of research to define a good goal, so give this step the attention it requires.

In my own job, I’ve found that it’s easy to come up with reasonable sounding problems, but that these problems often fail to hold my attention. In order to achieve consistent deep work, I usually need to first immerse myself in the relevant research literature, seeking a problem that it is recognized as important, unanswered, but probably answerable with my skill set. This is not easy.

Step #3: Stretch

Take your clear overall goal from the previous step and identify the next logical chunk of work (we’re talking about a chunk that can be accomplished in a small number of sessions, whereas the overall goal might take weeks to complete). When you tackle this chunk, push for a result that is beyond — but not too far beyond — what’s comfortable for your current skill level.

This is the cornerstone of the whole philosophy, so let’s take this slow…

If you can breeze through this chunk like you’re cranking a widget, then you’re not stretching yourself enough.

You need to design this chunk to feature enough difficulty that you quickly get stuck. At this point, you should slow down, and advance deliberately, in a state of real mental strain. This is where you might need to bring in expert coaching — e.g., turn to a textbook or ask a colleague.

This stretch is important to: (a) extract the most out of your current abilities; and (b) ensure that your abilities continue to improve.

Finding chunks that require stretch, but are not so hard that you get permanently blocked, is non-trivival, but is also something that will improve with practice. Keep in mind that most knowledge workers implicitly go out of their way to avoid a feeling of stretch at all costs (because it’s uncomfortable and much less fun than replying to some more e-mails) so by seeking it out, you’ve already put yourself on a much more ambitious trajectory.

In my own job, this is where I need the most improvement. I’ve observed that when I’m working on a proof intuition, if the math needed to formalize the idea gets tricky, I flee the strain, mark the intuition as “probably right,” and move on to something else. Step #3 tells me that this is exactly where I need to slow down and move deliberately, embracing the strain generated by reducing intuition to algebra (a process that often sends me back to my basic textbooks or pestering colleagues). This feeling of strain is the feeling of getting better at my profession, which is why I’m dedicating so much attention toward learning to embrace it.

Step #4: Obsess

The nice thing about deep work is that it’s a clear state of mind. You begin a session with a well-defined ritual, you work on a stretch chunk for 1 – 3 hours, then you finish and go rest. This clarity allows you to track how much time you spend in the state. This tracking gives you a number to try to improve.

You’ll be surprised by how little time you naturally spend doing deep work. You’ll also be surprised by how quickly you can increase these numbers once you know what you’re looking for and are keeping track of what you’re doing.

In my own job, I’ve occasionally used an hour tally to keep track of how much time I spend working on hard research projects. I’ve found, however, that this strategy was often too vague, as I could pump up those counts doing what was essentially shallow work related to a hard project. The specificity of the deep work routine described above, however, eliminates such abuses. The only time I now track is the time spent in this state of deep contemplation. If I can increase the time spent in this state, I’m confident that good things will follow.

(Photo by sparre.enger)

#deepwork

November 7, 2012

My New Project

October 31, 2012

Productivity is Not Dead, Just Downgraded

The Cautious Return of Nuts and Bolts Productivity

Last year, around this same time, I wrote an article titled Welcome to the Post-Productivity World. In it, I claimed that we had moved on from the early 2000′s dream that David Allen, teamed with the Lifehacker RSS feed, could deliver us to a knowledge work nirvana — a place where success and distinction flowed effortlessly from a well-tuned task-management system.

The attention of the online world, I noted, had shifted toward bigger questions, like “how do I make my work the foundation of a good life?”. Building a remarkable career, we now know, has little to do with organization, and very much to do with focusing ruthlessly on a small number of important skills and becoming so good you can’t be ignored.

And yet…

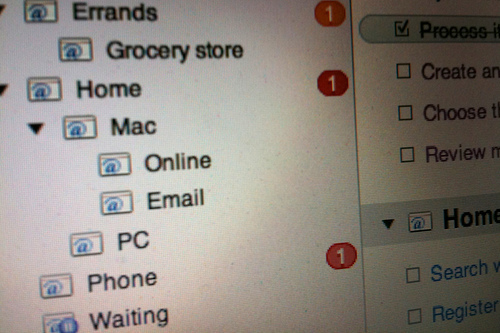

Now that I’m a professor, I realize that I miss productivity. It’s still true that my level of organization has little to do with my success as a scholar. It’s also true, I’m discovering, that it has everything to do with my stress level.

I spend much of my time focusing deeply on important projects. But I still have a lot of small things to get done in the time that surrounds this concentration. And without a thoughtful system, these tasks are getting done fitfully, often driven by deadlines — causing unnecessary stress.

So this gives us a new vision of productivity. We have dethroned it from its prior role as the center of our workplace universe, but it still plays an important (albeit, downgraded) role as a stress reliever.

I am, in other words, re-embracing nuts and bolts productivity. (God help me, but I just spent 10 minutes browsing the web page for OmniFocus!) But I’m doing so with caution. I want to tune up my organizational systems, but I also want to remember that these systems play only a supporting role in my bigger effort to craft a remarkable career.

Now excuse me while I shift my context…

(Photo by tsmall)

October 26, 2012

Mastering Linear Algebra in 10 Days: Astounding Experiments in Ultra-Learning

The MIT Challenge

My friend Scott Young recently finished an astounding feat: he completed all 33 courses in MIT’s fabled computer science curriculum, from Linear Algebra to Theory of Computation, in less than one year. More importantly, he did it all on his own, watching the lectures online and evaluating himself using the actual exams. (See Scott’s FAQ page for the details of how he ran this challenge.)

That works out to around 1 course every 1.5 weeks.

As you know, I’m convinced that the ability to master complicated information quickly is crucial for building a remarkable career (see my new book as well as here and here). So, naturally, I had to ask Scott to share his secrets with us. Fortunately, he agreed.

Below is a detailed guest post, written by Scott, that drills down to the exact techniques he used (including specific examples) to pull off his MIT Challenge.

Take it away Scott…

How I Tamed MIT’s Computer Science Curriculum, By Scott Young

I’ve always been excited by the prospect of learning faster. Being good at things matters. Expertise and mastery give you the career capital to earn more money and enjoy lifestyle perks. If being good is the goal, learning is how you get there.

Despite the advantages of learning faster, most people seem reluctant to learn how to learn. Maybe it’s because we don’t believe it’s possible, that learning speed is solely the domain of good genes or talent.

While there will always be people with unfair advantages, the research shows the method you use to learn matters a lot. Deeper levels of processing and spaced repetition can, in some cases, double your efficiency. Indeed the research in deliberate practice shows us that without the right method, learning can plateau forever.

Today I want to share the strategy I used to compress the ideas from a 4-year MIT computer science curriculum down to 12 months. This strategy was honed over 33 classes, figuring out what worked and what didn’t in the method for learning faster.

Why Cramming Doesn’t Work

Many student might scoff at the idea of learning a 4-year program in a quarter of the time. After all, couldn’t you just cram for every exam and pass without understanding anything?

Unfortunately this strategy doesn’t work. First, MITs exams rely heavily on problem solving, often with unseen problem types. Second, MIT courses are highly cumulative, even if you could sneak by one exam through memorization, the seventh class in a series would be impossible to follow.

Instead of memorizing, I had to find a way to speed up the process of understanding itself.

Can You Speed Up Understanding?

We’ve all had those, “Aha!” moments when we finally get an idea. The problem is most of us don’t have a systematic way of finding them. The typical process a student goes through in learning is to follow a lectures, read a book and, failing that, grind out practice questions or reread notes.

Without a system, understanding faster seems impossible. After all, the mental mechanisms for generating insights are completely hidden.

Worse, understanding is hardly an on/off switch. It’s like layers of an onion, from very superficial insights to the deep understandings that underpin scientific revolutions. Peeling that onion is often a poorly understood process.

The first step is to demystify the process. Getting insights to deepen your understanding largely amounts to two things:

Making connections

Debugging errors

Connections are important because they provide an access point for understanding an idea. I struggled with the Fourier transform until I realized it was turning pressure to pitch or radiation to color. Insights like these are often making connections between something you do understand and the material you don’t.

Debugging errors is also important because often you make mistakes because you’re missing knowledge or have an incorrect picture. A poor understanding is like a buggy software program. If you can debug yourself in an efficient way, you can greatly accelerate the learning process.

Doing these two things, forming accurate connections and debugging errors, is most of creating a deep understanding. Mechanical skill and memorized facts also help, but generally only when they sit upon the foundation of a solid intuition about the subject.

The Drilldown Method: A Strategy for Learning Faster

During the yearlong pursuit, I perfected a method for peeling those layers of deep understanding faster. I’ve since used it on topics in math, biology, physics, economics and engineering. With just a few modifications, it also works well for practical skills such as programming, design or languages.

Here’s the basic structure of the method:

Coverage

Practice

Insight

I’ll explain each stage and how you can go through them as efficiently as possible, while giving detailed examples of how I used them in actual classes.

Stage One: Coverage

You can’t plan an attack if you don’t have a map of the terrain. Therefore the first step in learning anything deeply, is to get a general sense of what you need to learn.

For a class, this means watching lectures or reading textbooks. For self-learning it might mean reading several books on the topic and doing research.

A mistake students often make is believing this stage is the most important. In many ways this is the least efficient stage because the amount you can learn per unit of time invested is much lower. I often found it useful to speed up this part so that I would have more time to spend on the latter two steps.

If you’re watching video lectures, a great way to do this is to watch them at 1.5x or 2x the speed. This can be done easily by downloading the video and then using the speed-up feature on a player like VLC. I’d watch semester-long courses in two days, via this method.

If you’re reading a book, I would recommend against highlighting. This is processes the information at a low level of depth and is inefficient in the long run. A better method would be to take sparse notes while reading, or do a one-paragraph summary after you read each major section.

Here’s an example of notes I took while doing readings for a class in machine vision.

Stage Two: Practice

Practice problems are huge for boosting your understanding, but there are two main efficiency traps you can get caught in if you’re not careful.

#1 – Not Getting Immediate Feedback

The research is clear: if you want to learn, you need immediate feedback. The best way to do this is to go question-by-question with the solution key in hand. Once you’ve finished a question, check yourself against the provided solutions. Practice without feedback, or with delayed feedback, drastically hinders effectiveness.

#2 – Grinding Problems

Like the students who fall into the trap of believing that most learning occurs in the classroom, some students believe understanding is generated mostly from practice questions. While you can eventually build an understanding simply by grinding through practice, it’s slow and inefficient.

Practice problems should be used to highlight areas you need to develop a better intuition for. Then techniques like the Feynman technique, which I’ll discuss, handle that process much more efficiently.

Non-technical subjects, ones where you mostly need to understand concepts, not solve problems, can often get away with minimal practice problem work. In these subjects, you’re better off spending more time on the third phase, developing insight.

Stage Three: Insight

The goal of coverage and practice questions is to get you to a point where you know what you don’t understand. This isn’t as easy as it sounds. Often you can be mistaken into believing you understand something, but don’t, or you might not feel confident with a general subject, but not see specifically what is missing.

This next technique, which I call the Feynman technique is about narrowing down those gaps even further. Often when you can identify precisely what you don’t understand, that gives you the tools to fill the gap. It’s the large gaps in understanding which are hardest to fill.

The technique also has a dual purpose. Even when you do understand an idea, it provides you opportunities to create more connections, so you can drill down to a deeper understanding.

The Feynman Technique

I first got the idea from this method from the Nobel prize winning physicist, Richard Feynman. In his autobiography, he describes himself struggling with a hard research paper. His solution was to go meticulously through the supporting material until he understood everything that was required to understand the hard idea.

This technique works similarly. By digesting the big hairy idea you don’t understand into small chunks, and learning those chunks, you can eventually fill every gap that would otherwise prevent you from learning it.

For a video tutorial of this technique, watch this short video.

The technique is simple:

Get a piece of paper

Write at the top the idea or process you want to understand

Explain the idea, as if you were teaching it to someone else

What’s crucial is that the third step will likely repeat some areas of the idea you already understand. However, eventually you’ll reach a stopping point where you can’t explain. That’s the precise gap in your understanding that you need to fill.

From that gap, you can research the answer from a textbook, teacher or online. Generally, once you’ve narrowly defined your misunderstanding it becomes much easier to find the precise answer.

I’ve used this technique hundreds of times, and I’ve found it can tackle a wide variety different learning situations. However, since each might be slightly different, it may seem hard to apply as a beginner, so I’ll try to walk through some different examples.

For Ideas You Don’t Get At All

The way I handle this is to go through the technique but have the textbook open to the chapter explaining that concept. Then I go through and meticulously copy both the author’s explanation, but also try to elaborate and clarify it for myself. This “guided” Feynman can be useful when trying to write anything on your own would be impossible.

Here’s an example I used for trying to understand photogrammetry.

For Procedures

You can also use the method to fully understand a process you need to use. Go through all the steps and explain not only what they do, but how they execute it. I would often go through proof techniques by carefully explaining all the steps. I also used it in understanding chemical equations or in organizing the stages of glycolysis in biology.

You can see this example I used when trying to figure out how to implement grid acceleration.

For Formulas

Formulas should be understood, not just memorized. So when you see a formula, but can’t understand how it works, try walking through each part with a Feynman.

Here’s an example I used for the Fourier analysis equation.

For Checking Your Memory

Feynmans also offer a way to self-test your knowledge of the big ideas for non-technical subjects. Being able to finish a Feynman on a topic without referencing the source material means you understand and can remember it.

Here’s one I did for an economics class, recalling the concept of predatory pricing.

Developing a Deeper Intuition

Combined with practice questions, the Feynman technique can peel those first few layers of understanding. But it can also drill deeper if you want to go from not just having an understanding, but to having a deep intuition.

Understanding an idea intuitively isn’t easy. Once again, getting to this point is often seen as a quasi-mystical process. But it doesn’t have to be. Most intuitions about an idea break down into one of the following types:

Analogies – You understand an idea by correctly recognizing an important similarity between it and an easier-to-understand idea.

Visualizations – Abstract ideas often become useful intuitions when we can form a mental picture of them. Even if the picture is just an incomplete representation of a larger, and more varied, idea.

Simplifications – A famous scientist once said that if you couldn’t explain something to your grandmother, you don’t fully understand it. Simplification is the art of strengthening those connections between basic components and complex ideas.

You can use the Feynman technique as a way of encouraging these types of insights. Once you’ve gotten past a basic understanding of the idea, the next step is to go further and see if you can explain it using some combination of the three methods above.

The truth is plagiarism is okay too, and not every insight needs to be unique. Understanding complex numbers as being two dimensional is hardly original, but it allows a useful visualization. DNA replication working like a one-way zipper is not a perfect analogy, but so long as you understand where it overlaps, it becomes a useful one.

The Strategy to Learn Faster

Learning faster doesn’t need to be a trick to work well. It simply means recognizing what is actually going on when we reach a new level of insight and finding tools to help us reach those stages consistently.

In this article I described learning as being three stages: coverage, practice and insight. This gives the false impression that these three occur always in distinct phases and never overlap or repeat.

In truth you may find yourself going between them in a loop as you successfully peel down to deeper layers of understanding. The first time you read a chapter you may get only superficial insights, but after doing practice questions and building intuitions, you may go back and read for deeper understandings.

Applying the Drilldown Method for Non-Students

This process isn’t one you need to be a student to apply. It also works for learning complex skills or building expertise on a topic.

For skills like programming or design, most people follow the first two stages. They read a book teaching them the basics, then they practice with a project. You can extend that process however, and use the Feynman technique to better lock in and articulate the insights you create.

For expertise on a topic, the only difference is that, prior to doing coverage, you need to find a set of material to learn from. That could be research articles or several books on the topic. In either case, once you’ve defined the chunk of knowledge you want to master, you can drill down and learn it deeply.

To find out more about this, join Scott’s newsletter and you’ll get a free copy of his rapid learning ebook (and a set of detailed case studies of how other learners have used these techniques).

(Image by afagen.)

October 23, 2012

The Joys and Sorrows of Deep Work

An Autumn Adventure

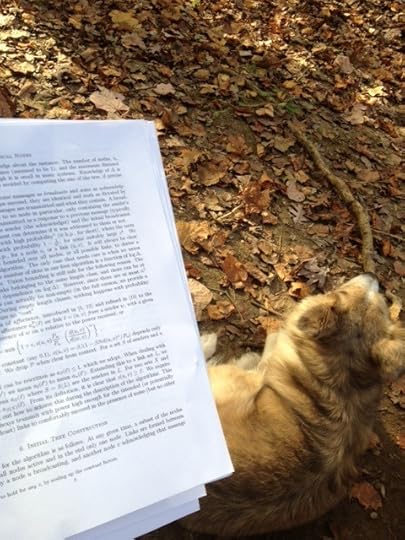

To help increase the attention I dedicate to literature-driven research projects, I’ve spent the last couple weeks immersing myself in a new area of my field. Today, for example, I thought the warm weather called for some adventure work. As shown above, I took some papers, a notebook, and my dog into the woods to grapple with some of these new ideas.

Here’s the thing: this type of immersion can be frustrating.

I spent hours today doing intellectual battle with a set of formalisms that still largely confuse me. In the long run, I know this type of battle is crucial (past experience has shown that even just a few dozen hours of such grappling can lay the foundation for multiple publications). But in the short run, it leaves me feeling like I accomplished nothing concrete with my day. (An unfortunate corollary of intellectual immersion is that it doesn’t work if you take time off to answer e-mails or do laundry — ensuring your to-do list remains untouched.)

So here we face a paradox. The very type of deep work that provides the nutriment for remarkable results also defies all our instincts for how a productive day should feel. I don’t have a specific set of strategies to suggest here. Instead, I just want to point out that when it comes to our understanding of how to build towards something important in our working life, there is a lot that our current conversation about work — which focuses on themes like courage, passion and productivity — seems to be missing.

October 11, 2012

The Importance of Auditing Your Work Habits

An Autumn Audit

I had to travel unexpectedly last weekend, so I missed my normal household chores. This morning, I woke up to the lawn picture above. Because I don’t have class or meetings scheduled today (a miracle!), I decided to take an hour or so to clean things up.

I never mind working outside, as it has the nice effect of moving my thoughts beyond the immediate future, and allowing me to perform a bigger picture audit of where things stand in my life. Today, I was thinking a lot about my work habits.

By the time I had the lawn looking like this…

…I had wrapped up some nice epiphanies.

Standing on Shoulders in Search of Important Problems

As I worked, my mind wandered to earlier this week, when I hosted a visiting scholar at Georgetown. He had recently published a nice result.

Some quick background: there is a network-related algorithm problem — how quickly can you schedule a connected structure in a wireless network with additive interference — that was introduced in 2006, and has received steady attention since. The first known solution required time relative to the logarithm of the network size raised to the fourth power, but this was quickly knocked down to cubic and then quadratic, where it has stalled since 2007. That is, until earlier this year, when my visitor, working with his collaborator, dropped the result down to the straight logarithm, which is almost certainly the best you can do.

This is an example of what I call an important result, because there’s a community of researchers who immediately recognized its value (in this case, because it improved a bound that lots of people had been trying, and failing, to improve). For an applied mathematician, important results are the bread and butter of a successful academic career.

Naturally, I asked the visitor about how he came to his big finding.

The short answer was reading. He had been trying to understand another important result in his field, which had been published the year before, and in doing so stumbled onto a technique that allowed his breakthrough.

This knowledge-driven approach to breakthroughs should sound familiar, as it turned up again and again in my previous study of the impact instinct. I also detail the phenomenon in Rule 4 of SO GOOD. To summarize: new important results almost always require expert-level knowledge of existing important results.

The implication is that, as an academic, I should be spending a significant portion of my time reading and trying to understand the best work in my field. As I raked and mowed this morning, I performed an internal audit, and came to the conclusion that although I do this, I’m not doing it nearly enough if I want to make a big splash.

My Skewed Project Ratio

Here’s the problem that’s keeping me from more time diving into the existing literature in search of important problems…

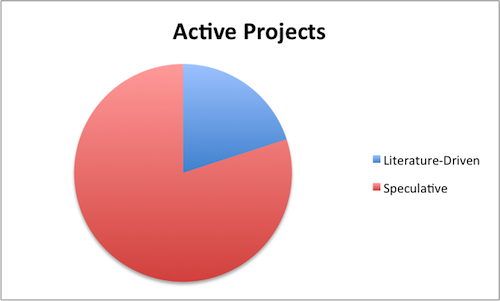

I currently have 10 projects that I consider active (i.e., they receive regular attention). Only 2 of these projects are aimed at improving results that are well-known in the existing literature. The other 8 are speculative, by which I mean my collaborators and I essentially invented them.

To be clear, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with speculative projects, especially when you’re combining disciplines (which almost always requires new problems to be identified). But they take time to maintain, are prone to fizzling (when you invent a problem there’s always a good chance that it will end up either trivial or impossible), and because they’re new, you tend to get less recognition for them once published. Eight such projects is too many.

A better mix for me would be 2 – 3 literature-driven projects and perhaps no more than 2 speculative projects at a time. The reduced load would allow me to advance results faster, so I wouldn’t expect my overall rate of publishing to reduce. But it would also skew my output so that at least half of my papers are geared toward potential important results. This is a much better ratio for a pre-tenure theoretician.

There’s no mystery as to how I fell into my current unequal balance: speculative projects are easy to start, while literature-driven projects can be difficult to find and always require lots of struggling with hard papers .

Which is why I’m glad I performed an audit this morning: If I had relied on the behaviors that were appealing in the short term, I would have continued to sell short my long term success.

Conclusion

The above details on how one produces important applied mathematics results are unlikely to be relevant to your career. But the bigger picture conclusion here is relevant: we should all regularly perform audits where we ask ourselves how we are currently spending our work time and how we should be spending this time. This sounds like a basic idea, but few of us actually do it. The lesson I’ve learned is that the best practices for a specific job are not always obvious without reflection. Furthermore, you can’t trust your instincts to lead your day-to-day decisions toward the best outcomes. Craftsmanship, in other words, requires guidance.

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

Solutions Beyond the Screen: The Adventure Work Method for Producing Creative Insights

Henri Poincare’s Four-Hour Work Day

You Probably (Really) Work Way Less Than You Think

Experiments with the Textbook Method

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

October 1, 2012

My Article in the New York Times and Other Miscellanea

I wanted to share a few notes about the SO GOOD launch and some related material that caught my attention recently…

Here’s an article I wrote on passion for this Sunday’s New York Times. If you’re looking for a concise description of the thesis of SO GOOD — perhaps to share with a passion-obsessed friend or relative — this article is a great way to do it. (As shown on the right, the article moved onto the list of the top 10 most e-mailed articles on the Times this morning, so hopefully the idea is spreading!)

Here’s an article I wrote on passion for this Sunday’s New York Times. If you’re looking for a concise description of the thesis of SO GOOD — perhaps to share with a passion-obsessed friend or relative — this article is a great way to do it. (As shown on the right, the article moved onto the list of the top 10 most e-mailed articles on the Times this morning, so hopefully the idea is spreading!)

If you’re still looking for more about the book, check out the article I wrote for the Harvard Business Review Blog (still one of their most read articles of the past month), or the excerpt that ran at FastCompany.com.

In the meantime, on an unrelated note, my friends, The Minimalists, just published a new book: $5 Simplicity. If you’re interested in living a simpler and more meaningful life, few commentators are more thoughtful than Ryan and Josh — definitely check it out. (Also check out their blog; they’re about to move into a Walden-style cabin in Montana…should make for interesting reading.)

Also unrelated to the book, Daphne Gray-Grant has recently launched a series chronicling her experiments in applying the principles of deliberate practice to writing. Thought some of you might enjoy hearing about her adventures in career craftsmanship.

As the busyness generated by my book launch begins to fade, I’m excited to return soon to my normal style of posts. I have a lot to share about my most recent attempts and thoughts regarding the quest for a remarkable career…

September 24, 2012

Zipcar CEO’s Dangerous Advice on Passion

Problematic Passion

The Wall Street Journal’s At Work blog recently featured an interview with Zipcar CEO, Scott Griffith. The title worried me: Zipcar CEO: “If You Don’t Have Passion for Your Job, Quit.”

Sure enough, in the interview, Griffith recalls that he had an interest in technology and transportation as early as junior high school. He then generalizes widely:

[W]e all kind of know what our passions are pretty early in life, and if you can figure out a way to align your avocation with your vocation, the sky’s the limit for your career and your happiness.

This, of course, is the standard thinking on career satisfaction. As readers of my new book know, it’s also dangerous advice. To reiterate: most young people do not have a clear passion. In fact, it’s unclear what “passion” really means at this stage. Is it a hobby? An obsession? A vague interest?

Griffith is well-intentioned. And to be fair, he also precedes the above with the caveat, “it may not be that clear to everybody.” But ultimately he’s still reinforcing a dangerous trope: that we’re all hard-wired for a specific profession.

As I’ve argued, this belief leads young people to anxiety and disillusionment when the reality of work doesn’t match their dream job ideal. For most, passion must be cultivated over time, as part of a more general process of building skills and then leveraging these skills to control our career.

Put another way: passion is a great goal, but unless you’re exceptionally lucky, it requires more than just a little day dreaming in the back of a junior high classroom.

#####

At around 6:00 pm this evening, I drew the winners for my one-on-one conversation contest. They have been notified by e-mail. Thank you everyone who entered. I wish I could speak to each of you individually, but with well over 150 book purchases submitted, I would have been glued to the phone for the foreseeable future!

In other book news, you might enjoy this excerpt from SO GOOD which ruffled some feathers over at Fast Company. Turns out people really like Steve Jobs. Who knew?

(Photo by crschmidt)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers