The Importance of Auditing Your Work Habits

An Autumn Audit

I had to travel unexpectedly last weekend, so I missed my normal household chores. This morning, I woke up to the lawn picture above. Because I don’t have class or meetings scheduled today (a miracle!), I decided to take an hour or so to clean things up.

I never mind working outside, as it has the nice effect of moving my thoughts beyond the immediate future, and allowing me to perform a bigger picture audit of where things stand in my life. Today, I was thinking a lot about my work habits.

By the time I had the lawn looking like this…

…I had wrapped up some nice epiphanies.

Standing on Shoulders in Search of Important Problems

As I worked, my mind wandered to earlier this week, when I hosted a visiting scholar at Georgetown. He had recently published a nice result.

Some quick background: there is a network-related algorithm problem — how quickly can you schedule a connected structure in a wireless network with additive interference — that was introduced in 2006, and has received steady attention since. The first known solution required time relative to the logarithm of the network size raised to the fourth power, but this was quickly knocked down to cubic and then quadratic, where it has stalled since 2007. That is, until earlier this year, when my visitor, working with his collaborator, dropped the result down to the straight logarithm, which is almost certainly the best you can do.

This is an example of what I call an important result, because there’s a community of researchers who immediately recognized its value (in this case, because it improved a bound that lots of people had been trying, and failing, to improve). For an applied mathematician, important results are the bread and butter of a successful academic career.

Naturally, I asked the visitor about how he came to his big finding.

The short answer was reading. He had been trying to understand another important result in his field, which had been published the year before, and in doing so stumbled onto a technique that allowed his breakthrough.

This knowledge-driven approach to breakthroughs should sound familiar, as it turned up again and again in my previous study of the impact instinct. I also detail the phenomenon in Rule 4 of SO GOOD. To summarize: new important results almost always require expert-level knowledge of existing important results.

The implication is that, as an academic, I should be spending a significant portion of my time reading and trying to understand the best work in my field. As I raked and mowed this morning, I performed an internal audit, and came to the conclusion that although I do this, I’m not doing it nearly enough if I want to make a big splash.

My Skewed Project Ratio

Here’s the problem that’s keeping me from more time diving into the existing literature in search of important problems…

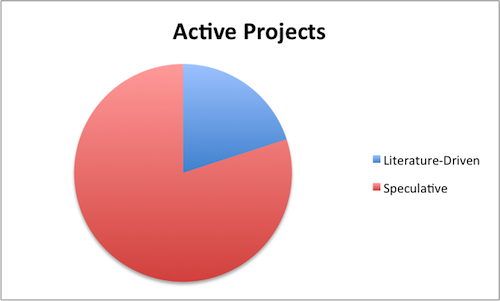

I currently have 10 projects that I consider active (i.e., they receive regular attention). Only 2 of these projects are aimed at improving results that are well-known in the existing literature. The other 8 are speculative, by which I mean my collaborators and I essentially invented them.

To be clear, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with speculative projects, especially when you’re combining disciplines (which almost always requires new problems to be identified). But they take time to maintain, are prone to fizzling (when you invent a problem there’s always a good chance that it will end up either trivial or impossible), and because they’re new, you tend to get less recognition for them once published. Eight such projects is too many.

A better mix for me would be 2 – 3 literature-driven projects and perhaps no more than 2 speculative projects at a time. The reduced load would allow me to advance results faster, so I wouldn’t expect my overall rate of publishing to reduce. But it would also skew my output so that at least half of my papers are geared toward potential important results. This is a much better ratio for a pre-tenure theoretician.

There’s no mystery as to how I fell into my current unequal balance: speculative projects are easy to start, while literature-driven projects can be difficult to find and always require lots of struggling with hard papers .

Which is why I’m glad I performed an audit this morning: If I had relied on the behaviors that were appealing in the short term, I would have continued to sell short my long term success.

Conclusion

The above details on how one produces important applied mathematics results are unlikely to be relevant to your career. But the bigger picture conclusion here is relevant: we should all regularly perform audits where we ask ourselves how we are currently spending our work time and how we should be spending this time. This sounds like a basic idea, but few of us actually do it. The lesson I’ve learned is that the best practices for a specific job are not always obvious without reflection. Furthermore, you can’t trust your instincts to lead your day-to-day decisions toward the best outcomes. Craftsmanship, in other words, requires guidance.

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

Solutions Beyond the Screen: The Adventure Work Method for Producing Creative Insights

Henri Poincare’s Four-Hour Work Day

You Probably (Really) Work Way Less Than You Think

Experiments with the Textbook Method

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9951 followers