Cal Newport's Blog, page 57

September 18, 2012

My New Book and a Chance to Speak with Me One-On-One

The cake my wife surprised me with to celebrate the release of my new book.

The Education of a Writer

I wrote my first book when I was 21. At the time, I thought it would be an interesting, one-time challenge. But it didn’t take long before a more ambitious goal emerged. I decided that I wanted to one day write a big deal hardcover idea book, in the style of the non-fiction authors I admired, such as Steven Johnson and Bill McKibben.

It took me two more books, a stellar agent, and a decade of training, but today I finally fulfilled that goal. My first hardcover idea book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You, is now available. It will be on the New Arrival table at Barnes & Noble stores across the country and available in all relevant online stores and digital formats.

This is an exciting day for me and one that never would have happened without you, my readers here at Study Hacks, who have helped me hone my arguments and my craft. So I humbly thank you.

(And if you’re looking for a way to show your appreciation for Study Hacks, buying a copy of this book is a great way to demonstrate your support!)

This brings me to today’s post. I have two goals in the sections below: (1) to tell you a little bit more about the book; and (2) to tell you how you can win a chance to speak with me one-on-one about any topic of your choosing.

Onwards to the details…

“Follow Your Passion” is Bad Advice. Here’s What Works Instead…

In the fall of 2010, I set out to answer a simple question: “Why do some people love what they do, while so many others do not?”

This quest took me across the country. I met with organic farmers, venture capitalists, computer programers, college professors, med school residents, and globe-trotting tech entrepreneurs, among many others, all in an effort to understand how people cultivate compelling careers.

My new book chronicles this quest and what I discovered.

In more detail, the book is divided into the following four “rules,” each cataloging a different discovery:

Rule #1: Don’t Follow Your Passion. Here I make my argument that “follow your passion” is bad advice. You’ve heard me talk about this on Study Hacks, but in this chapter, I lay out my full-throated, comprehensive, detailed argument against this common advice.

Rule #2: Be So Good They Can’t Ignore You. Here I detail the philosophy that works better than following your passion. This philosophy, which I call career capital theory, says that you first build up rare and valuable skills and then use these skills as leverage to shape you career into something you love. During this chapter I spend time with a professional guitar player, television writer, and venture capitalist, among others, in my quest to understand how people get really good at what they do. You’ll also encounter a detailed discussion of deliberate practice and how to apply it in your working life.

Rule #3: Turn Down a Promotion. Here I argue that control is one of the most important things you can bargain for with your rare and valuable skills. I discuss the difficulties people face in trying to move toward more autonomy in their working lives and describe strategies that can help you sidestep these pitfalls. During this chapter, I spend time with a hotshot database developer, an entrepreneurial medical resident, an Ivy League-trained organic farmer, and Derek Sivers, among others, in my attempts to decode control.

Rule #4: Think Small, Act Big. In this final rule, I explore how people end up with career-defining missions — often a source of great passion. I argue that you need rare and valuable skills before you can identify a powerful mission. I then spend time with a star Harvard professor, a television host, and a Ruby on Rails guru, all in an effort to identify best practices for cultivating this trait.

I conclude the book by talking about how I apply these ideas in my own career. You’ll hear about my academic job search process and the types of systems I have in place to help push me toward more and more passion in my work.

If you’re serious about loving what you for a living, and are tired of people reducing this complex goal to a simple slogan (“do what you love! the money will follow”), then this book is perfect for you. (If you’re on the fence, check out the endorsements from folks like Seth Godin, Reid Hoffman, Dan Pink, Kevin Kelly, and Derek Sivers, or the growing number of unsolicited 5-star reviews).

Purchase details: You can buy the hardcover at most book stores and online at Amazon, B&N.com, 800-CEO-READ, and IndieBound. The book is also available in Kindle , Nook, and audio formats.

Talk One-On-One With Me

To help motivate you to buy the book during this crucial first week I’m offer a promotion in which I’m giving away 30 minute, one-on-one phone calls with myself, to talk about any topic of your choosing.

Here are the details…

I am holding three separate random drawings: one for people who preordered the book; one for people who buy the book this week; and one for people who buy five or more copies of the book. (Not very many people buy in bulk, so if you do, you’ll probably have a good chance of being drawn).

To apply, simply forward your receipt to interesting@calnewport.com with the subject line [contest: preorder], [contest: 1 copy], or [contest: 5 copies], depending on which contest you’re entering. (It’s important that you use this exact wording and capitalization or your entry might be missed by my filters.)

I will use random.org to draw winners from each category next Monday. The number of winners I draw will depend on how many entries I receive.

If you win, I’ll notify you by e-mail, and we’ll set up a time to chat on the phone.

September 14, 2012

Steve Jobs’s Complicated Views on Passion

Jobs Parses Passion

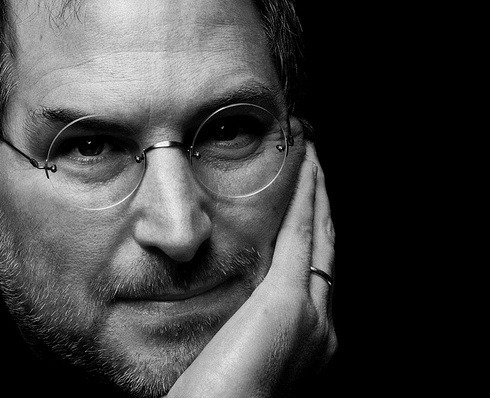

At a recent media panel, Walter Isaacson remembered the following conversation with the late Steve Jobs:

I remember talking exactly a year ago right now to Steve Jobs, who was very ill…He said, “Yeah, we’re always talking about following your passion. But we’re all part of the flow of history… you’ve got to put something back into the flow of history that’s going to help your community…[so] people will say, this person didn’t just have a passion, he cared about making something that other people could benefit from.”

Isaacson also shared his own views on the passion hypothesis:

Every baby boom generation person who has to give a college commencement talk uses the phrase “follow your passion.” But that’s why no one has written a book calling us the greatest generation. The important point is to not just follow your passion but something larger than yourself. It ain’t just about you and your damn passion.

The specific advice given above is interesting. But to me, what’s even more interesting is the general point that building a meaningful working life is damn complicated. “Follow your passion” is a nice slogan, but as Jobs and Isaacson emphasize, there’s a lot more involved in building a career you’re proud of.

Put another way, “follow your passion” is like the kiddie’s pool of life advice. It’s time to take off the floaties and dive into the deep end.

If only there was a book about how to do this…

September 10, 2012

I Want to Give You a Free Copy of My New Book

My new book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work You Love, will be published in eight days! If you haven’t already pre-ordered the book, sit tight: next week I’ll do the official announcement, which will include some exciting giveaways for people who buy a copy then.

In the meantime, two pieces of pre-pub business…

If You Pre-Ordered the Book, Please Consider Leaving an Amazon Review

If You Pre-Ordered the Book, Please Consider Leaving an Amazon ReviewThis is me in favor asking mode: If you pre-ordered the book from Amazon, and received your copy early, please consider leaving an honest review. I want the people who consider the book during the publication week to encounter some social proof that I’m not a crank.

If you do leave a review, please e-mail me at interesting [at] calnewpot.com with the subject line “[Review]” so that I can thank you personally. Feel free to include in your e-mail any questions or comments you had about the book.

I look forward to hearing from you!

If You Have a Platform, I Have a Free Book for You

My publisher has given me a limited number of electronic copies of the book to give away. If you have an online platform (e.g., a blog, a big twitter following) that you think might be interested in my ideas, I want to give you one of these free copies. In exchange, I will ask that you share your honest thoughts about the book with your audience on (or near) the 9/18 publication date.

If you’re interested send me an e-mail at interesting [at] calnewport.com with the subject line “[Platform].” Please include a link to your platform and audience size, just in case I end up with more requests than books!

September 5, 2012

Solutions Beyond the Screen: The Adventure Work Method for Producing Creative Insights

Fog marching down the Berkeley hills (photo by Ianan).

Battling the Beast

A couple weeks ago, I made a brief visit to Berkeley, California, for a wedding. My wife, Julie, had to take a conference call the first morning after we arrived, so I decided to get some work done myself. I didn’t bring a computer, so “work” couldn’t mean e-mail replying (the standard instinct in this situation).

Instead, I decided to log some hard focus hours on what I like to call The Beast: a particularly vexing theory problem that my collaborators and I have been battling for many months.

I got some coffee and headed toward the Berkeley campus on foot. It was early, and the fog was just starting its march down the Berkeley hills (as shown above).

I eventually wandered into a eucalyptus grove:

(Photo by letjoysize)

Once there, I sipped my coffee and thought.

Our existing strategy for The Beast included a complicated algorithm which none of us looked forward to analyzing. Deploying a trick I learned while a grad student, I avoided needing to understand why the complicated algorithm worked by instead turning my attention to understanding why simpler strategies failed (I’m surprised by how often the study of things that break lead to simple things that don’t).

After only an hour, which included a strategic fill-up at the Free Speech Cafe, I had an idea for a more concise (and easier to analyze) algorithm that seemed to work.

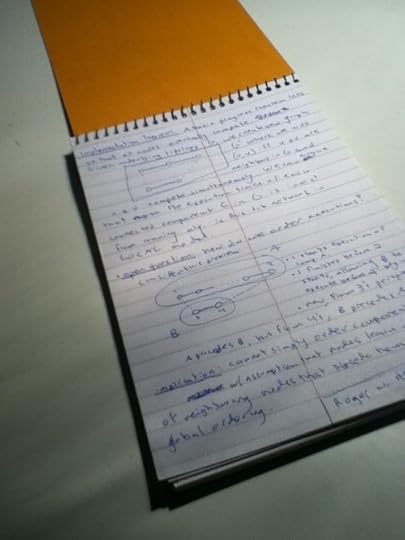

I realized, however, that there’s a limit to the depth you can reach when keeping an idea only in your mind. Looking to get the most out of my new insights, and inspired by my recent commitment to the textbook method, I trekked over to a nearby CVS and bought a 6 x 9 stenographer’s notebook.

(I discovered this notebook style when writing HIGHSCHOOL SUPERSTAR, much of which I outlined while walking by the Charles River — they’re sturdy and easy to use when not at a desk).

I then forced myself to write out my thoughts more formally:

This combination of pen and paper notes with the exotic context in which I was working ushered in new layers of understanding. Our battle with The Beast continues, but in the latest draft of our solution in progress, these Berkeley simplifications play a useful role.

Adventure Work

I’m telling this story because it sparked a realization. Back in my student advice days, I was a promoter of adventure studying — a tactic where you tackle schoolwork in exotic locations, such as here…

…where one of my readers prepared for an important Chinese exam (which he aced), or here…

…which is a view from the rooftop of a campus building where another of my readers would sneak out to crack tricky problem sets.

The motivation for adventure studying was two-fold:

Changing your context makes the work seem fresh and allows you to tackle it with new creativity and energy.

Going somewhere exotic separates you from common distraction urges.

My experience in Berkeley helped me realize that this same adventure tactic should work for non-student work as well. When faced with a core responsibility — something that draws on and develops the ability that makes you rare and valuable — the same two motivations listed above apply to adventure work just as much as adventure studying.

This explains why a couple hours outside in the eerily unchanging northern California weather could produce more insight than days of work back at my office.

Do you adventure work? If so, share your story and a photo…

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

Henri Poincare’s Four-Hour Work Day

You Probably (Really) Work Way Less Than You Think

Experiments with the Textbook Method

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

August 31, 2012

Henri Poincaré’s Four-Hour Work Day

John Cook, an applied mathematician and blogger, recently highlighted the following quote from a new biography of Henri Poincaré:

Poincaré … worked regularly from 10 to 12 in the morning and from 5 till 7 in the late afternoon. He found that working longer seldom achieved anything …

At first, we might marvel at how little time Poincaré spent working. But then we realize that “work” in this context probably means super-intense, hard-focused, uber-concentration; the type of “work” that required him to ponder things like a triangulated homology 3-sphere (pictured to the right).

At first, we might marvel at how little time Poincaré spent working. But then we realize that “work” in this context probably means super-intense, hard-focused, uber-concentration; the type of “work” that required him to ponder things like a triangulated homology 3-sphere (pictured to the right).

Still, it doesn’t seem that hard to get 4 hours of hard focus out of an 8 – 10 hour work day. Most probably assume that they hit this mark easily. But then we measure this assumption and get a cold dose of reality.

At which point, we stop marveling at Poincaré’s supposed laziness, shut down our e-mail, and turn back to the metaphorical (or, in my case, literal) chalkboard.

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

You Probably (Really) Work Way Less Than You Think

Experiments with the Textbook Method

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

August 29, 2012

Following Passion is Different than Cultivating Passion

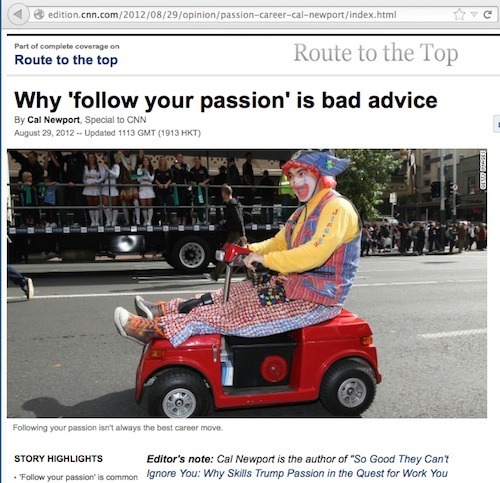

My article from CNN.com, featuring what is arguably the creepiest photo ever associated with a discussion of career advice.

Concerning Comments

Earlier today, CNN.com published an article I wrote. It summarizes the main idea from my new book: “follow your passion” is bad advice.

What interests me are the comments on the CNN website. Here’s a sample quote:

Following you passion should be a given. What’s the point of life if you’re a robot on a factory line…

As Study Hacks readers will notice, this commenter completely misunderstood my point. He thought I was arguing that you shouldn’t aim for a career that you feel passionate about. This couldn’t be more distant from the truth. I think passion is great. But it’s not something that you “follow” (which implies you can identify it in advance). It’s instead something you have to purposefully cultivate over time.

The key observation here is that the majority of the 60+ comments on the website made a similar mistake. I think this tells us something important about the American cultural conversation surrounding career satisfaction. The reason “follow your passion” has such a hold on our thinking is that many mistakenly equate this strategy with the generic and near-tautological statement that it’s good to love your job.

Of course it’s good to love your job. But “following” your passion suggests something more specific — a strategy that’s not supported by the evidence.

My challenge here is clear: To successfully spread this idea to a larger audience I need to be careful to separate the goal of developing passion from the flawed strategy of following it. (If you want to help me in this challenge, consider retweeting the CNN article with a more accurate description; e.g., “Don’t follow passion, cultivate it“).

August 23, 2012

You Probably (Really) Work Way Less Than You Assume

The 6-Hour Work Week

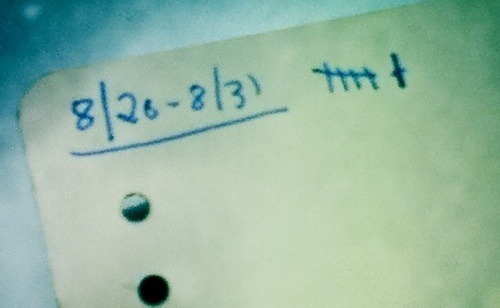

Last weekend, I decided it would be an interesting experiment to start tracking the hours I spent in a state of hard focus. I only counted hours where I was mastering new material (e.g., with the textbook method), engaging in a serious research discussion, or trying to formally write up new results.

I have done such tracking before, but not recently. I figured it would provide a helpful metric for my craftsman in the cubicle project. Here’s my tally for the four days I’ve tracked so far:

It’s depressing.

I have caveats — I was traveling through late Monday night and I was at a retreat most of the day yesterday — but still. I’m embarrassed by how few hours I managed to spend on work that really matters.

I have a general and a specific conclusion to make here…

The general conclusion: I think most knowledge workers probably way overestimate how much time they actually spend improving and applying the core skills that make them valuable. Keep a similar tally for a week, you’ll be surprised by what you find. This underscores the importance of the type of project I’m running here: if we don’t apply deliberate efforts in our quest to become craftsmen, our progress will be glacial. On the flip side, if we do apply these efforts, we have an opportunity to jump far ahead in our value.

The specific conclusion: As the summer gives way to the school year, I have my work cut out for me. I’m going to continue to track these hours for the near future, and let this tally drive me toward the hard decisions necessary to continue my quest to become “so good they can’t ignore you.”

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

Experiments with the Textbook Method

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

August 16, 2012

Experiments with the Textbook Method

Tailoring the Textbook Method

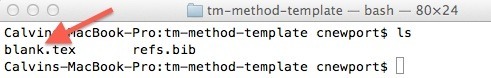

I spent this past week experimenting with the textbook method. I began by creating a template — a blank LaTex document — for collecting research notes:

When compiled into a pdf, it looks like this:

My plan was to minimize friction when starting work on a new idea or project — all I have to do now is copy the blank document to a new directory, change the title, and start capturing notes.

With my system in place I could take it out for a spin.

I decided to apply the method to a big hairy graph theory problem that my collaborators and I have been battling for months. This big problem keeps branching off into many promising smaller problems, one of which I have been pursuing recently with my grad student. This sub-problem provided a perfect case for applying the method.

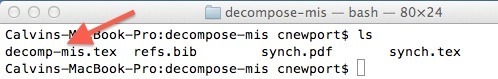

I started a new write-up to capture, in my own words, what we thought we knew so far:

This well-constructed plan worked well…for about twenty minutes.

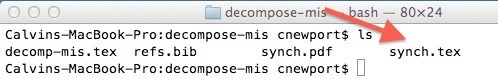

As I was writing, this process of formalization led me to a new approach to the idea. I quickly generated a new blank document (easy to do now that I have a template) and spent the rest of the afternoon, textbook open in front of me, office whiteboard filling with diagrams, trying to work though the details:

At first, I felt somewhat uneasy about leaving that first document half-written. My task-oriented instinct is to finish each write-up, once started. Instead I had abandoned the document as soon as something more relevant popped onto my radar.

But on reflection, I think what is happening — rapid idea abandonment and spawning – is exactly what I want from the method. The write-ups, I must remind myself, are not a goal in themselves (most likely, no one will ever see them). They’re instead a tool to induce fast learning, and this fast learning, in turn, increases the rate at which I can explore a problem space — exactly what I need in my research.

To summarize: I’m testing this method in my applied mathematics research, but it’s becoming clear that it should work equally as effectively in most scenarios where you need to master complicated things fast — be it a new programming language or marketing strategy. We’ll see how it holds up as I apply it to multiple concurrent projects and more complicated topics.

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

August 10, 2012

Hacking Education with Udemy

I few times a year, I offer to write an honest review about a relevant product if the company is willing to donate to a charity of my choice. Udemy, a web site that makes it easy to take and design courses online, recently took me up on my offer, donating money to Urban Teaching Center, a D.C.-area non-profit that sends highly-qualified teachers to the schools that need them most.

Hacking Education

Education is being disrupted. There’s near universal agreement on this point.

Experts can now reach students directly online. These students, in turn, can now hack their education experience — building valuable expertise in exactly the areas they need, all for a fraction of the cost of traditional schooling. (If you doubt the power of this disruption, check out Scott Young’s MIT Challenge.)

The question now is what will this new world look like?

Udemy, an online education platform, offers a glimpse of this future. I recently spent an entertaining morning exploring this site, and was impressed by the scope of their offerings: over 1000 courses in topics that range from geeky (I was drawn to Zed Shaw’s Learn Python the Hard Way) to artistic (Carol Robinson’s free Music Theory course has over 2700 students).

Turning toward the details, the underlying idea driving Udemy is simple: the site makes it easy to both take and offer courses (free and paid).

The most basic courses consist only of video lectures. The more advanced courses mix video lectures with workbooks, samples, and sometimes audio that can be downloaded to your iPod.

All the courses I sampled provide lifetime access (once you buy the course, the material is yours forever) and a 30-day guarantee (a sign of confidence given that 30 days is enough to watch all the material for most courses).

The platform is cleverly setup so that you can access your courses from any Internet-connected device, and the user interface is crisp and intuitive.

Summary: As the education model continues to be disrupted, there will be lots of sites trying to match students with teachers. Udemy’s advantage is that they’re taking the time to get the details right.

You Know What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Less Than Ultra Learning

The surprisingly useful Riemann Zeta function in action. (Image from MathWorld.)

As part of my craftsman in the cubicle project, I spent this past week monitoring how I learn new information.

I wasn’t impressed.

At one point, for example, I needed to dive into a topic I didn’t know much about: how information disseminates in random power law graphs. I went to Google Scholar and begin downloading papers with promising abstracts. I printed three and skimmed another half-dozen or so online. In retrospect, I think I was hoping to find a theorem somewhere that described exactly what I was looking for in notation I already understood.

Not surprisingly, I didn’t find this magic theorem. The two hours I spent felt wasted. (Well, not completely wasted, I did learn about the Riemann Zeta function, which turns up way more often than you might expect.)

This experience recommitted me to cracking the code of ultra-learning. Mastering hard knowledge fast, I now accept, requires more than blocking aside time on a schedule; it also demands technique.

The Chair

With this in mind, here was my first stab at cracking ultra-learning:

[image error]

I bought a traditional leather chair (a longtime dream of mine). My wife and I still need to add some bookcases, a rich rug, and an old brass lamp — but my general theory here is that this library nook will be make it impossible to avoid mastering new bodies of knowledge, and perhaps also pipe smoking.

Under the assumption that I might need more than the power of The Chair to become an accomplished ultra-learner, I do have one more strategy to deploy — which is what I want to talk about in this post. It’s actually a strategy I’ve known for years (my PhD adviser taught me soon after my arrival at MIT), but have seemed to forgotten recently.

The Textbook Method

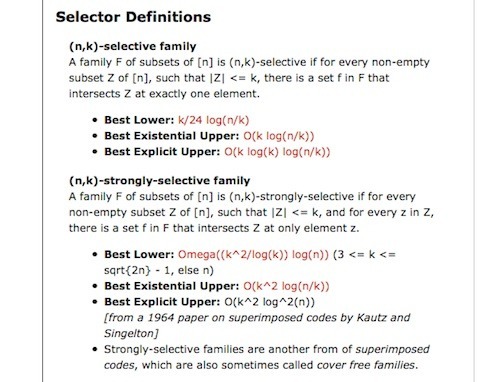

This screenshot is from a web page I built as a grad student:

I needed to know about a certain family of combinatorial object sometimes called selectors. I actually needed to know quite a bit about these things because my collaborators and I wanted to prove the existence of a new one. My approach to this learning challenge was to build an annotated bibliography that listed every known result, with citations.

The web page took me a couple (hard) hours to make, which is roughly the same time I wasted this week “studying” power law graphs. I’ve probably used this knowledge on a dozen different occasions since, and I know at least two other scholars that have used it in their own research.

Here we have a nice comparison. In two cases I spent roughly the same amount of time trying to learn new knowledge. In one case, I efficiently mastered a new area, while in another, I ended up frustrated.

The comparison highlights the power of a simple act: describing and organizing information in your own words.

I call this the textbook method as you’re essentially writing your own textbook on a topic. One thing I like about it is that it works nicely with different levels of required detail. Whether you just need to organize what’s known about a subject, or build a deeper understanding of how results are derived, the textbook method seems to extract an optimum amount of learning out of the time spent.

It also leaves a written record that’s easy to reference later when you need to deploy the information.

Over the next week or two I’m going to take this method for a spin by applying it to some tough learning challenges in my queue. I’ll report back what I learn. I invite you to join me in this endeavor. Pick your own challenge, apply the textbook method, keep us updated in the comments below.

In the meantime, if you need me, I’ll be in my chair.

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers