Experiments with the Textbook Method

Tailoring the Textbook Method

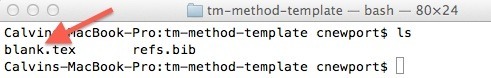

I spent this past week experimenting with the textbook method. I began by creating a template — a blank LaTex document — for collecting research notes:

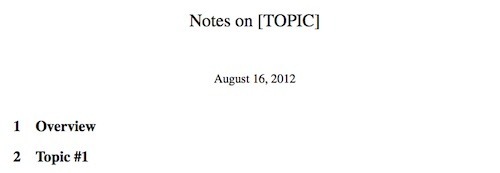

When compiled into a pdf, it looks like this:

My plan was to minimize friction when starting work on a new idea or project — all I have to do now is copy the blank document to a new directory, change the title, and start capturing notes.

With my system in place I could take it out for a spin.

I decided to apply the method to a big hairy graph theory problem that my collaborators and I have been battling for months. This big problem keeps branching off into many promising smaller problems, one of which I have been pursuing recently with my grad student. This sub-problem provided a perfect case for applying the method.

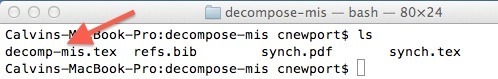

I started a new write-up to capture, in my own words, what we thought we knew so far:

This well-constructed plan worked well…for about twenty minutes.

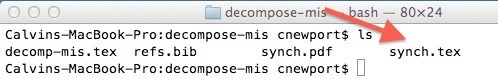

As I was writing, this process of formalization led me to a new approach to the idea. I quickly generated a new blank document (easy to do now that I have a template) and spent the rest of the afternoon, textbook open in front of me, office whiteboard filling with diagrams, trying to work though the details:

At first, I felt somewhat uneasy about leaving that first document half-written. My task-oriented instinct is to finish each write-up, once started. Instead I had abandoned the document as soon as something more relevant popped onto my radar.

But on reflection, I think what is happening — rapid idea abandonment and spawning – is exactly what I want from the method. The write-ups, I must remind myself, are not a goal in themselves (most likely, no one will ever see them). They’re instead a tool to induce fast learning, and this fast learning, in turn, increases the rate at which I can explore a problem space — exactly what I need in my research.

To summarize: I’m testing this method in my applied mathematics research, but it’s becoming clear that it should work equally as effectively in most scenarios where you need to master complicated things fast — be it a new programming language or marketing strategy. We’ll see how it holds up as I apply it to multiple concurrent projects and more complicated topics.

#####

This post is part of my Craftsman in the Cubicle series which explores strategies for building a remarkable working life by mastering a small number of rare and valuable skills. Previous posts include:

You Are What You Write: The Textbook Method for Ultra-Learning

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

#craftsmanincubicle

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers