Cal Newport's Blog, page 55

March 3, 2013

How Can Two People Feel Completely Different About the Same Job? — Career Drift and the Danger of Pre-Existing Passion

The Emersonian Doctoral Candidate

I’m flying down to Duke on Tuesday to speak with their graduate students. Preparing for the event inspired me to reflect on my own student experience. In doing so, an Emerson quote came to mind:

“To different minds, the same world is a hell, and a heaven”

Emerson does a good job of capturing the reality of a research-oriented graduate education. Even though students enter such programs — especially at top schools — strikingly homogenous, in terms of their educational backgrounds and achievements, after a few years, the group tends to radically bifurcate.

Some students love the experience and thrive. They dread the possibility that they might have to one day leave academia and take a “normal job.” To them, graduate school is Emerson’s heaven.

Other students hate the experience and wilt. They complain about their advisors, and their peers, and the school, and their busyness. They can’t wait to return to a “normal job.” To them, graduate school is Emerson’s hell.

I began to notice this split about halfway though my time at MIT. I loved graduate school, so I was mildly surprised, at first, to encounter cynical students secretly plotting to abandon ship after earning their masters degree, or to stumble into dark blogs with titles such as, appropriately enough, Dissertation Hell (” a place to rant…about the tortures of writing a dissertation”).

Why do such similar students end up with such different experiences?

Because I happened to be a professional advice writer at the same that I was a student, I studied the issue. I think the answers I found are important to our broader discussion because this Emersonian division is common in many professions, and understanding its cause helps us better understand the complicated task of building a compelling career and the pitfalls to avoid.

Directed vs. Drifting Careers

Graduate students who experience Emerson’s heaven tend to aggressively seek out and develop expertise. Once they have this expertise, they use it as leverage to control their project choices, collaborators, and workflow.

The students who experience Emerson’s hell are more passive. They approach graduate school like college — waiting to be assigned tasks that they can work real hard to complete. Their theory is that hard work alone should yield good results. This theory, of course, is flawed.

When you’re passive about the direction of your student experience, you tend to end up with projects you do not like, bogged down with tasks no one else wanted to do. Over time you’ll begin to see the work as a negative force — leading to cynicism and diminishing motivation.

This division is important because it applies to many different professions. The employees (or entrepreneurs) who thrive tend to actively direct their career using the tenets of Career Capital Theory, just like the successful graduate students.

Those who struggle tend to drift through their working life, hoping, usually in vain, that by simply working hard and doing what they’re told, they’ll end up with a compelling livelihood.

The Passion Pitfall

Their two reasons to discuss these observations. The first is positive: when you understand the dynamics of crafting a compelling career you’re better able to harness them in your own life.

The second reason is negative: Understanding the difference between directed and drifting careers underscores the danger of common career advice; most notably, the ubiquitous entreaty to “follow your passion.”

Apologists for this reductionist theory often claim that it’s worth propagating, because if it helps even one person build the courage to pursue a dream, the effort becomes worthwhile.

But as emphasized by the above discussion, things are not so simple.

Here’s what worries me: When you persuade someone to obsess over the match between their work and a mysterious, innate, pre-existing passion (which, for some reason, we assume everyone has, even though the evidence suggests the opposite), you’re setting them up for career drift. Passion theory says that your passion pre-exists, so when you find the right job, it will be right from day one.

In reality, as we’ve just seen, a particular job is not likely to become a source of passion until you’ve been actively directing it — sometimes for years — in the right direction.

By telling someone to “follow their passion,” therefore, you are, quite ironically, reducing the probability that they’ll end up passionate about their work.

To put things another way, the division between Emerson’s heaven and hell is permeable and one we should all hope to cross in the right direction. But we need to understand that this is an active effort, conducted over time, and not the result of a simple match made at the very beginning of our career.

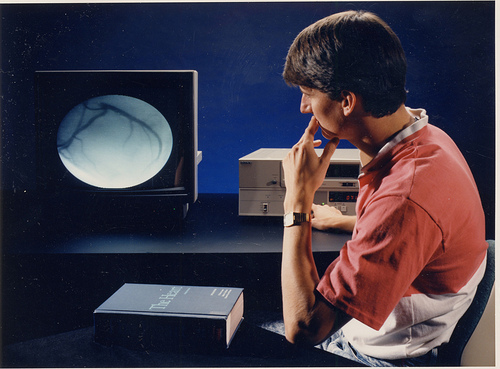

(Photo by USUHSPAO)

February 26, 2013

On the Art of Ambition

Ambition as an Art Form

I’m fascinated by people who accomplish things of importance. I’m also fascinated by how little we understand this process.

Traditional career thinking, of course, says you must identify your passion then aggressively pursue it. As you know, I have little patience for such childish reductionism.

When we start thinking about our career aspirations like adults, and ask hard questions, the answers tend to be more complex.

When I studied this issue in the context of academia, for example, I found instead that famous researchers often had surprisingly subtle — and well-developed — strategies for pursuing important results.

Consider Richard Feynman and Richard Hamming. Both of these stars talk about a robust process in which they systematically built up collections of open problems, and then, over time, tested out new techniques against these problems, always sifting for a match. This approach required a careful balance between seeking new knowledge and working with what they already knew. I suspect they dedicated a lot of thought to tuning this balance.

The broader point here is that ambition is good. But it’s not simple.

At some point, you have to turn your attention from the advice of commentators whose main credential is success in providing advice, and actually steep yourself in the nuance of how people make remarkable things happen in your field. I am increasingly convinced that this apprenticeship, which can be long and often ambiguous, is a necessary stepping stone on the path to big things.

February 17, 2013

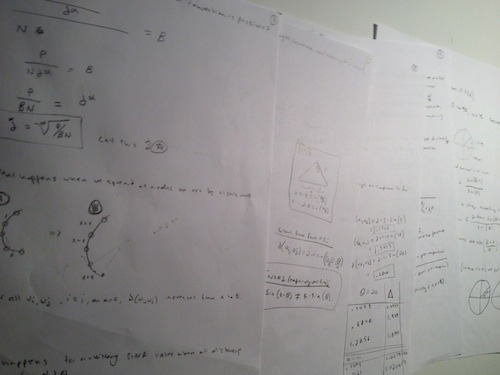

The Single Number that Best Predicts Professor Tenure: A Case Study in Quantitative Career Planning

An Interesting Experiment

How do people succeed in academia?

I have notebooks filled with theories about this question, but I’ve increasingly come to realize that insights of this type — built on gut instinct, not data — are close to worthless. Most knowledge work fields are complex. Breaking into their upper levels requires a deliberate effort and precision that is poorly matched to the blunt, feel-good plans we devise in bouts of blog-inspired reflection.

This was on my mind when, earlier this week, I went seeking empirical insight into the above prompt, and ended up designing a simple experiment:

I started by identifying well-known professors in my particular niche of theoretical computer science.

For each such professor, I studied their former graduate students. I was looking for pairs of students who earned their PhD around the same time and went on to research positions, but then experienced markedly different levels of success in the field.

Once I had identified such a pair, I studied the first four years of their CVs — the crucial pre-tenure period — measuring the following variables: quantity of publications, venue of publications, and citation of published work in the period.

Each such pair provided an example of a successful and non-successful early academic career. Because both students in a pair had the same adviser and graduated around the same time, I could control for variables that are largely outside the control of a graduate student, but that can have a huge impact on their eventual success, including: school connections, quality of research group, and the value of the adviser’s research focus.

The difference in each pair’s performance, therefore, should be due to differences in their own strategy once they graduated. It was these strategy nuances I wanted to understand better.

Here’s what I found…

The successful young professors published a lot. On average, they published 25 conference papers during their first four years. The non-successful professors published only 10. (Recall, in computer science, it’s competitive conference publications, not journal publications, that matter.) There was, however, high variance in these numbers. I was struck more by the floor function: the successful professors all published at least 4 conference papers a year (with some, but not all, publishing quite a bit more).

Neither the successful nor non-successful professors strayed far from the key conferences in their niche. In theoretical computer science, each niche has its own publication venues, arranged in tiers of quality. There are also a small number of more general venues, which cover all of theoretical computer science, and which are quite competitive and prestigious. Neither of the groups I studied published much in the elite general venues. Both groups published mainly in the quality venues within their niche.

The biggest differentiating factor between the two groups was citations. For each professor, I counted the citations for their five most cited papers published during their first four years (according to Google Scholar). The difference was staggering. The successful professors’ most cited papers from this period received, on average, over 1000 references. For the non-successful professors, the number was closer to 60.

As mentioned, I have notebooks filled with different strategies for succeeding in my research, with each such strategy focusing on a different element that struck me as important at the time.

My above experiment sweeps these compelling sounding ideas off the proverbial table, and replaces them with an approach backed by data. What matters, it tells me, is something we can call: quality cited papers. In more detail, how many papers per year are you publishing that: (a) are in quality venues; and (b) attracting citations?

This metric can tell me if I’m improving or not from year to year. Similarly, it provides clear feedback on which of my research directions should be dropped and which emphasized. When deciding whether to join a project, for example, I should start by estimating the expected impact on my quality cited papers value for the year. When deciding whether to apply for a particular grant, the same question should guide the decision.

This metric, in other words, plays the role for a young professor that batting average plays for a young baseball player. You might not like what it has to say, but it’s saying what you need to hear.

Quantitative Career Planning

The above experiment is a case study of a bigger idea that intrigues me. In knowledge work, we spend shockingly little time trying to understand the reality of how people in our positions succeed. Perhaps, as I’ve argued recently, we prefer our own answers to the truth, as our answers tend to sidestep any efforts that are too hard.

But it’s also possible that we simply need a better method for seeking these insights. The process above, which we can call quantitative career planning (a reference to the quantified self movement that encapsulates it), is an example of what these better methods might look like.

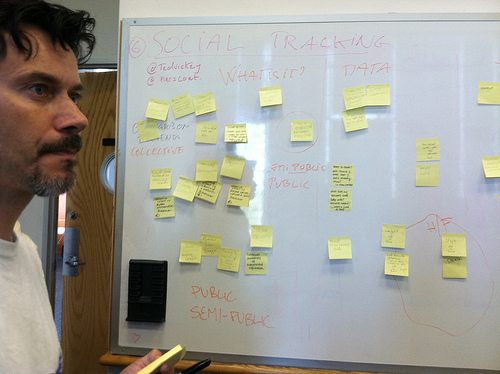

(Photo by bytemarks)

February 5, 2013

You Need to Master the Rules Before You Can Reinvent Them

A Useful Rejection

Earlier in my career, I submitted a grant proposal to a prestigious program. At the time, I had an interesting research idea bouncing around, so when I saw the deadline approach, I hunkered down for a week of deep work to pull together a submission.

A few months later, while at a workshop, I met the head of the funding program. I told her about my proposal.

“I assume,” she said, “that you had the very best people in your field read it over first.”

I had not.

Soon after this encounter, I received my rejection notification.

Evidence-Based Betting

Reflecting on this experience, I now notice that in my rush to embrace deep work and purposeful bets I had overlooked a more prosaic piece of the puzzle: learning the rules that govern the area where I was making my play.

If I had followed the program director’s advice and pumped experts for feedback, I would have learned about what you absolutely need for a fundable proposal. I avoided this step, I think, because some part of me didn’t want these answers. By writing my grant in isolation, I could ensure an optimal experience, where I had to put in focused hours, but never really challenge myself too much.

This was fulfilling. But it was also a recipe for failure.

I was like the amateur runner who spends her training days doing hard (but not too hard) three mile jogs instead of the brutal interval work she really needs to improve.

I don’t think we emphasize enough the importance of evidenced-based metrics. Deep work is important. Making lots of bets is important. But if these efforts are not grounded in the reality of your field — including the hard truths about what you really do need to potentially succeed, not just what you know how to do — they are wasted.

February 3, 2013

Do You Need Passion to Succeed as an Entrepreneur? Pam Slim’s Advice for Starting Your Own Business

Start-Up Passion

In So Good They Can’t Ignore You, I argue that “follow your passion” is bad advice.

But what about for entrepreneurs?

I’m asked this question often. It seems logical that the only way to power through the difficulties of starting a new business is to be driven by passion, so people want to know if this path is an exception to my post-passion philosophy.

This is an important question and I want to provide an evidence-based answer. With this in mind, I turned to Pamela Slim, author of Escape from Cubicle Nation, and one of the country’s top thinkers on making the jump to entrepreneurship. I met Pam last summer and was impressed by the sophistication of her thinking on this topic, so I asked if I could interview her and then share her thoughts with you. She graciously agreed.

Here are the highlights from our conversation (my conclusion follows)…

“In terms of starting a business, the first step for many people — particularly those in traditional corporate environments — is to tune into what topics interest you, where your natural strengths are, what lights you up.”

“For many people, however, there is no one thing — we are wired to have many different interests and passions.”

“You have to choose something of interest that is also going to have an economic engine behind it.”

“Take one idea. Find a simple business model. Then test it using the fewest resources possible (time, energy, money), but in a way that gives you a good sense of whether the idea is viable. This is especially important if you are testing an idea while still holding a traditional job.”

“If you put a number of different models through this test, you can determine if you enjoy doing it, and if the market really finds it to be valuable. You need both.”

“I suggest having a clear decision criteria.”

“A word of warning about this process: something I’ve seen people struggle with is this idea that there’s a perfect job or business out there for you. Then, when you start something, and it’s not everything it’s cracked up to be, you worry, when you should instead be committing to building the skills necessary.”

“If you are always attempting to understanding yourself better, identifying environments that support your best work, then commit yourself to do your best work, it will lead to more happiness.”

My Conclusion

When it comes to entrepreneurship, Pam knows her stuff, so I was happy to see that our thinking aligns in so many places. The idea that most caught my attention is the difference between passion and a true calling.

Pam notes that it’s important to feel strongly about a business model/idea/lifestyle before pursuing it. In fact, she frequently uses the word “passion” to describe this feeling.

But she also makes it clear that there’s a difference between this strong feeling and a sense that a particular path is the one and only path for you. It’s this latter thinking that so often leads to worry and disappointment when reality proves less than euphoric. She notes that you might have many different interests, and this fine — choose one. And even if you love the idea you’re pursuing with a singular intensity, you still need to commit to clear and objective testing of the market. Without an “economic engine”, all the passion in the world cannot guarantee you long term reward and engagement.

January 13, 2013

“Write Every Day” is Bad Advice: Hacking the Psychology of Big Projects

A Flawed Axiom

Write every day.

If you’ve ever considered professional writing, you’ve heard this advice. Stephen King recommends it in his instructional memoir, On Writing (he follows a strict diet of 1,000 words a day, six days a week). Anne Lamott proposes something similar in her guide, Bird by Bird (she recommends sitting down to write at roughly the same time every day).

Having published four books myself, here’s my opinion: If you’re not a full time writer (like King and Lamott), this is terrible advice. This strategy will, in fact, reduce the probability that you finish your writing project.

In this post, I want to explain why this is true — as this explanation provides insight into the psychology of accomplishing big projects in any field.

The Planning Brain

Here’s what happens when you resolve to write every day: you soon slip up.

If you’re not a full-time writer, this is essentially unavoidable. An early meeting at work, a back-up on the subway, an afternoon meeting that runs long — any number of common events will render writing impractical on some days.

This slip-up, however, has big consequences.

It provides evidence to your brain that your plan to write every day will not succeed. As I’ve argued before, the human brain is driven, in large part, by its need to assess plans: providing motivation to act on good plans, and reducing motivation (which we experience as procrastination) to act on flawed plans.

The problem for the would-be writer is that the brain does not necessarily distinguish between your vague and abstract goal, to write a novel, and the accompanying specific plan, to write every day, which you’re using to accomplish this goal.

When the specific plan fails, the resulting lack of motivation infects the general goal as well, and your writing project flounders.

Freestyle Writing

In my experience as a writer with a day job, I’ve found it’s crucial to avoid rigid writing schedules. I don’t want to provide my brain any examples of a strategy related to my writing that’s failing.

When I’m working on a book, I instead approach each week as its own scheduling challenge. I work with the reality of my life that week to squeeze in as much writing as I can get away with, in the most practical manner. Sometimes, this might lead to stretches where I write every morning. But there are other periods where I might balance a busy start to the work week with half days of writing at the end, and so on.

The point is that I commit to plans that I know can succeed, and by doing so, I keep my brain’s motivation centers on board with the project.

Misunderstanding Motivation: Knowledge Trumps Productivity

This approach, of course, brings up the question of motivation. Most people who embrace the daily writing strategy do so because they worry their will to do the work will diminish without a fixed system to force progress.

This understanding is flawed.

You can’t force your brain to generate motivation. It will do so only when it believes in both your goal and your plan for accomplishing the goal.

If you find that you’re still failing to get work done, even when you’re more flexible with your scheduling, the problem is not your productivity, it’s instead that your mind is not yet sold that you know how to succeed with your general goal of becoming a writer.

In this case, abandon National Novel Writing Month (which I think trivializes the long process of developing writing craft) and go research how people in your desired genre actually develop successful careers. Your mind requires a reality-based understanding of your goal in addition to achievable short-term plans.

Generalizing to Non-Writing Projects

I recalled this lesson recently in an unrelated part of my life. One of my interests over the past few months has been trying to increase the amount of time I spend engaged in deep work related to my academic research.

In December, I tested a rigid strategy that was, in hindsight, just as doomed to failure as attempting to write every day. I had a particular paper that I wanted to complete in time for a winter deadline. I told myself that the key is to start every weekday with deep work. If I commuted on the subway, I would work in a notebook while traveling. If I drove, I would knock off a batch at home while waiting for rush hour to end.

I believed this rigid schedule would help make deep work an ingrained habit, and the paper would get done with time to spare.

It reality, I crashed and burned.

The first week, I successfully followed my plan two days out of five — failing the other days for the types of unavoidable scheduling reasons I mentioned above, as well as the fact that writing in my notebook on the subway turns out to make me nauseous!

After that week, my brain revoked any vestige of motivation for this effort and my total amount of deep work plummeted.

My solution to this freefall was to take a page from my writing life. I went from rigid to flexible planning. I now approach each week with the flexible goal of squeezing in as much deep work toward my goal as is practically possible.

Some weeks I squeeze in more than others. Every week looks different. But what’s consistent is that I’m racking up deep hours and watching my paper starting to come together.

Because I am confident that I know how to accomplish my goal, and my efforts to do so are succeeding each week, my brain remains a supporter.

Summary

Hard scheduling rules — write every day! work on research for one hour each morning! exercise 10 hours a week! — deployed in isolation will lead to procrastination as soon as you start to violate them, which you almost certainly will do. At this point, the bigger goal the rules support will suffer from this same motivation drop.

To leverage the psychology of your brain, you need to instead choose clear goals that you clearly know how to accomplish, and then approach scheduling with flexibility. Be aggressive, but remain grounded in the reality of your schedule. If your mind thinks you have a good goal and sees your short terms plans are working, it will keep you motivated toward completion.

(Image from AJC1)

January 8, 2013

Two Books To Keep On Your New Year Radar

Two Recommendations

In general, January is a good month for books about productivity. This January is particularly good as two friends of mine, whose thinking on these topics I really respect, both have books out this week. Coincidentally, both of these friends asked me to write the foreword for their titles — which I was honored to do.

With this in mind, if you’re looking for some smart thinking on productivity (or want to experience some unusually thoughtful and erudite foreword writing), I recommend these new releases:

The 3 Secrets to Effective Time Investment by Elizabeth Grace Saunders

Elizabeth runs a successful consulting business that helps people make more meaningful use of their time. If you’re looking to focus less on the unimportant and more on what really matters, this book offers tested advice for achieving this goal.

The Front Nine by Mike Vardy

Mike is the former editor-in-chief of Lifehack.org — an experience that transformed him into a incisive commentator on what works and what doesn’t in the world of productivity. His new book takes a surprisingly nuanced look at what it (really) takes to get important projects from conception to completion.

January 2, 2013

Does Luck Matter More Than Skill?

Luck Over Skill?

The most provocative business title I’ve read recently is Frans Johansson’s The Click Moment. In this book, Johansson argues the following:

For activities with clear fixed rules — such as sports, chess, and music — the only way to succeed is to put in more deliberate practice than your peers. Johansson uses Serena Williams as a key example: her dad started her practicing tennis absurdly hard at an absurdly young age.

For activities with rapidly evolving rules – such as business start-ups or book writing — success comes when you change the rules to a new configuration that catches the zeitgeist just right. Johansson uses Stephanie Meyers, author of the Twilight series, as a key example. Meyers, in Johansson’s estimation, is not a good writer. Her first Twilight book reads more like fan fiction than a professionally-scribed genre novel. She had not, in other words, spent much time in a state of deliberate practice. But this didn’t matter. Something about her new take on vampire tales hit the cultural moment just right and earned her extraordinary renown. The lesson, according to Johansson, is that luck plays the central role in success for these activities. If you want to do something remarkable,therefore, you have to keep trying new things — placing, what he calls, purposeful bets — hoping to stumble into an idea that catches on.

Here’s the obvious follow-up question for Study Hacks readers: how do these ideas square with my skill-driven philosophy of building a remarkable life?

Schwarzenegger’s Serendipity

I gained insight into this question from another book I read recently (and found surprisingly engrossing): Arnold Schwarzenegger’s new autobiography, Total Recall.

At a high-level, Schwarzenegger’s story seems to validate Johansson’s serendipity-fueled vision of success. The young bodybuilder’s ascent in movies required several lucky breaks:

being brought to LA — of all possible cities — to train in Joe Weider’s Gold’s Gym;

meeting a writer, Charles Gaines, who was writing about the bodybuilding subculture at the time, and who helped introduce Schwarzenegger to many important players in Hollywood; and

starting to take acting seriously just as the the 1980s action movie trend generated a sudden need for larger than life characters who knew how to film a movie.

There was no way Schwarzenegger could have planned this rise to stardom. Serendipity played a big role.

But does this mean that deliberate practice and the striving to become so good they can’t ignore you is not so important? Schwarzenegger would disagree. Throughout his autobiography, he kept emphasizing that you “have to do the reps” — a reference to the unavoidable importance of putting in the hard work required to do something well.

When you dive deeper into his story, you notice that this dedication to skill-building plays a supporting role behind all of his lucky breaks:

he was brought to LA because he was the most promising bodybuilder of his generation, a status he achieved by starting his serious training at least two years earlier than most elite competitors, and adding a new level of intensity to his workouts;

when he arrived in America, he hustled: starting at least four different businesses (real estate, mail order, seminars and construction), taking night classes, and shadowing Joe Wieder on international business trips. His smarts and ambition is what helped him gain access to Charles Gaines’s circle of influential friends; and

when he began acting, he worked really hard at it. He took classes and trained intensely for small roles throughout the 70s, eventually winning a Golden Globe for “Best Acting Debut in a Motion Picture” for 1976′s Stay Hungry. In other words, Schwarzenegger wasn’t picked out of nowhere to star in 1982′s Conan the Barbarian (his big break). He was, at that point, a world famous bodybuilder who could act and was well-known in Hollywood circles. From this perspective, he was the obvious choice for the role.

The Serendipity Equation

The combination of The Click Moment and Total Recall has helped me developed a more nuanced understanding of how skill and luck interplay in the quest to do something remarkable. Being a math geek, I find that equations help me better capture the relative importance of different factors, and with this in mind, I came up with the following:

= x ,

where is a measure of the rareness and value of your relevant skills, and the value of the serendipitous factors is drawn from something like an exponential distribution.

In this equation, there are two variables.

The first is the potential of the project. The more rare and valuable your skills, generally speaking, the more potential you have for the project to succeed. This is something you control.

The second variable captures serendipity. You cannot predict or control this factor, but you can expect that really big values are really rare (hence the approximation to an exponential distribution).

This equation helps explain examples like Stephanie Meyer. Her project potential was low because she did not have much skill as a writer. But her serendipity factor was huge, swamping her low potential.

At the same time, the equation tells us that Meyer’s example is not a generally replicatable strategy. The huge serendipity factor she enjoyed is rare. You could launch 1000 low potential projects in your lifetime and never encounter anything close.

Objectively, the best strategy for success, given this equation, is to combine a commitment to increase your project potential as much as possible (by sharpening your rare and valuable skills), with a commitment to keep launching a steady stream of such projects and seeing them through to completion, increasing your chances of encountering high (though perhaps not Meyer’s-level) serendipity.

Without serendipity, your skill alone might not create the results you crave. At the same time, however, without a high project potential to multiply, the type of serendipity you can realistically expect to encounter if you try enough things, also won’t generate these results. You need both.

If you believe that something like this equation is true, then this approach of becoming as good as possible while trying many different projects, maximizes your expected success.

Indeed, we can call this the Schwarzenegger Strategy, as it does a good job of describing his path to stardom. Looking back at his story, notice that he tried to maximize the potential in every project he pursued (always “putting in the reps”). But he also pursued a lot of projects, maximizing the chances that he would occasionally complete one with high serendipity. His breaks, as described above, all required both rare and valuable skills, and luck. And each such project was surrounded in his life by other projects in which things did not turn out so well.

Summary: You cannot count on luck or skill to generate remarkable outcomes in isolation. The most consistent path to meaningful accomplishment seems to be a combination of the two. Pick a small number of things and become so good they can’t ignore you. Along the way, however, keep taking your growing skill out for a spin, launching related projects, one after another, carefully studying the outcomes to see if you stumbled into something big.

######

For more examples and tactics regarding this idea of launching exploratory projects in the search of breakthroughs, see chapters 13 and 14 of SO GOOD. For more on building rare and valuable skills, see chapter 7.

December 21, 2012

Getting (Unremarkable) Things Done: The Problem With David Allen’s Universalism

Getting Beyond Getting Things Done

I first read David Allen’s Getting Things Done (GTD) in 2003. I was a junior at Dartmouth and Allen’s ideas resonated at a time when my obligations were starting to overwhelm me. I committed to his system.

After a few years, by which time I was at MIT for graduate school, I found myself frustrated with the whole GTD canon and was ready to abandon it altogether.

My issue was simple: it wasn’t helping me become better.

I was good at full capture and regular review, and, accordingly, was quite organized. This was a good time in my life to ask me to submit a form or tackle a complicated logistical process. You could be confident that I would capture, process, and then accomplish it.

But I was missing the intense and obsessive wrangling with the hard problems of my field — the type of habit that made people in my line of work exceptional. My commitment to GTD had me instead systematically executing tasks, one by one, like an assembly line worker “cranking widgets” (to use a popular Allen aphorism).

I didn’t need to be cranking widgets. I needed to instead be crazily focused.

Allen’s Universalism

Here’s where we find my concern with GTD. In chapter 1, Allen emphasizes:

“[Y]ou can’t do a project…you can only do an action related to it. Many actions require only a minute or two, in the appropriate context, to move a project forward” (page 19; US paperback).

In chapter 2, he elaborates:

“When enough of the right action steps have been taken, some situation will have been created that matches your initial picture of the outcome closely enough that you can call it ‘done’” (page 38).

In Allen’s world, in other words, everything reduces to clear and easy-to-accomplish next actions. Whether the action is tied to a logistical annoyance (“buy more soap for the guest bathroom”) or tied to your deepest ambitions (“buy notebook to capture book ideas”) doesn’t matter. When you get down to the scale of execution, all actions are created equal.

This is part of what makes GTD so seductive. It tells you that if you organize your lists properly during your review, then you can tackle each day mechanically: mindlessly cranking through next actions like widgets, assured that not only will the little things get done, but also the big important life goals.

At least, that’s the idea. The problem, however, is that this is not the way remarkable things are actually accomplished.

Not All Work is Created Equal

Allen preaches task universalism: when you get down to concrete actions, all work is created equal.

I disagree with this idea.

Creating real value requires deep work, which is a fundamentally different activity than knocking off organizational tasks.

Deep work cannot be reduced to clear next actions. It is, instead, a philosophy that must be cultivated. If you read Robert Greene’s Mastery, for example, you’ll encounter story after story of remarkable people who didn’t carefully organize tasks, but instead marshaled their energy toward the obsessive (and often messy) pursuit of something new.

As a graduate student, I didn’t need better lists of next actions. I needed instead to be training my ability to focus hard on meaningful things for long periods of time — even after it becomes uncomfortable.

It’s here that Allen apologists might try to force these two worlds together. They might suggest, for example, that you could simply have a next action labeled: “spend many hours obsessively doing deep work on problem X.” But such efforts soon reveal their inadequacy.

Deep work is fundamentally different than the shallow (though still important) work of keeping on top of the little things required to function personally and professionally.

At least, this is the compromise I’ve adopted. I embrace GTD for organizing shallow work. It is, as many will attest, devastatingly effective for this purpose. But I think of deep work as something different altogether. A philosophy of life that requires its own strategies.

To Summarize: David Allen’s universalism is seductive, but ultimately flawed. Cranking widgets cannot create results of lasting value. That requires something deeper.

(Photo by tsmall)

December 13, 2012

This Holiday, Give the Gift of Career Confidence

A Gift that Keeps on Giving

If you’re still searching for holiday gifts, I want to humbly recommend my new book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You: Why Skills Trump Passion in the Quest for Work you Love.

As most of you know, this book makes the argument that “follow your passion” is bad advice. It then chronicles my (successful) quest to figure out the concrete strategies that work instead (hint: how you work is more important than what work you do).

If you already read the book and enjoyed it, think about your passion-addled friends and relatives who might benefit from hearing this advice.

If you haven’t read it, consider giving yourself the gift of a blueprint for building a remarkable career.

On the fence? Here are some accolades to help persuade you…

The book was selected for several Best of 2012 lists, including: Inc. Magazine’s Best 2012 Books for Entrepreneurs, The Globe and Mail’s Top 10 Business Books of the Year, 800-CEO-READ’s Business Book Awards Shortlist, and Small Business Trend’s Best Business Books of 2012.

My op-ed on the book for the New York Times spent a week as the paper’s #1 most e-mailed article, while my article on the book for the Harvard Business Review blog spent a month on the site’s most read articles list.

The book was endorsed by Seth Godin, Reid Hoffman, Dan Pink, Kevin Kelly and Derek Sivers (see Derek’s 10/10 review of the book).

Want to find out more? You can also read my summary of the book, or read (adapted) excerpts published in Fast Company, The Globe and Mail, and Lifehacker.

If you’re a college student (or thinking of buying the book for a student), read this thoughtful review from the Swarthmore College Daily Gazette.

If you’re interested: you can find the book at Barnes & Noble stores (it should be on the Best of Business display at most locations) and online at bn.com and Amazon.

#####

Okay, that’s the end of my pitch. We’ll return soon to our regularly scheduled programming. In particular, I’ve been working on an essay about why I think David Allen deters deep work.

Stay tuned…

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers