Getting (Unremarkable) Things Done: The Problem With David Allen’s Universalism

Getting Beyond Getting Things Done

I first read David Allen’s Getting Things Done (GTD) in 2003. I was a junior at Dartmouth and Allen’s ideas resonated at a time when my obligations were starting to overwhelm me. I committed to his system.

After a few years, by which time I was at MIT for graduate school, I found myself frustrated with the whole GTD canon and was ready to abandon it altogether.

My issue was simple: it wasn’t helping me become better.

I was good at full capture and regular review, and, accordingly, was quite organized. This was a good time in my life to ask me to submit a form or tackle a complicated logistical process. You could be confident that I would capture, process, and then accomplish it.

But I was missing the intense and obsessive wrangling with the hard problems of my field — the type of habit that made people in my line of work exceptional. My commitment to GTD had me instead systematically executing tasks, one by one, like an assembly line worker “cranking widgets” (to use a popular Allen aphorism).

I didn’t need to be cranking widgets. I needed to instead be crazily focused.

Allen’s Universalism

Here’s where we find my concern with GTD. In chapter 1, Allen emphasizes:

“[Y]ou can’t do a project…you can only do an action related to it. Many actions require only a minute or two, in the appropriate context, to move a project forward” (page 19; US paperback).

In chapter 2, he elaborates:

“When enough of the right action steps have been taken, some situation will have been created that matches your initial picture of the outcome closely enough that you can call it ‘done’” (page 38).

In Allen’s world, in other words, everything reduces to clear and easy-to-accomplish next actions. Whether the action is tied to a logistical annoyance (“buy more soap for the guest bathroom”) or tied to your deepest ambitions (“buy notebook to capture book ideas”) doesn’t matter. When you get down to the scale of execution, all actions are created equal.

This is part of what makes GTD so seductive. It tells you that if you organize your lists properly during your review, then you can tackle each day mechanically: mindlessly cranking through next actions like widgets, assured that not only will the little things get done, but also the big important life goals.

At least, that’s the idea. The problem, however, is that this is not the way remarkable things are actually accomplished.

Not All Work is Created Equal

Allen preaches task universalism: when you get down to concrete actions, all work is created equal.

I disagree with this idea.

Creating real value requires deep work, which is a fundamentally different activity than knocking off organizational tasks.

Deep work cannot be reduced to clear next actions. It is, instead, a philosophy that must be cultivated. If you read Robert Greene’s Mastery, for example, you’ll encounter story after story of remarkable people who didn’t carefully organize tasks, but instead marshaled their energy toward the obsessive (and often messy) pursuit of something new.

As a graduate student, I didn’t need better lists of next actions. I needed instead to be training my ability to focus hard on meaningful things for long periods of time — even after it becomes uncomfortable.

It’s here that Allen apologists might try to force these two worlds together. They might suggest, for example, that you could simply have a next action labeled: “spend many hours obsessively doing deep work on problem X.” But such efforts soon reveal their inadequacy.

Deep work is fundamentally different than the shallow (though still important) work of keeping on top of the little things required to function personally and professionally.

At least, this is the compromise I’ve adopted. I embrace GTD for organizing shallow work. It is, as many will attest, devastatingly effective for this purpose. But I think of deep work as something different altogether. A philosophy of life that requires its own strategies.

To Summarize: David Allen’s universalism is seductive, but ultimately flawed. Cranking widgets cannot create results of lasting value. That requires something deeper.

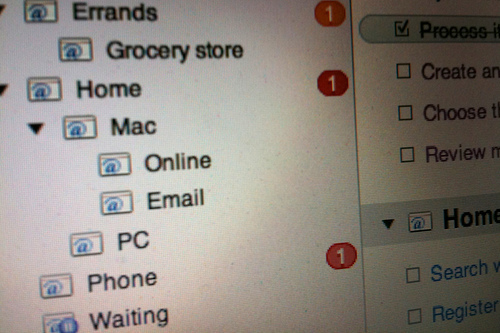

(Photo by tsmall)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers