Cal Newport's Blog, page 52

January 3, 2014

On Quiet Creativity

Outdoor Office

For a couple hours yesterday, the trails pictured above served as my office.

Earlier that morning, I was polishing a proof. In doing so, I needed to reference a pair of related papers. As I began reading these papers, I sensed a deep connection between these results and my own, but I couldn’t quite articulate it.

In my experience, this type of connection making is well-served by three ingredients: quiet, movement, and time. So I left my building and hiked onto a network of trails that abuts the Georgetown campus.

I spent the next couple of hours walking and thinking, trying to arrange and re-arrange my understanding of these results. I’m hoping this impromptu line of thought might yield something new and significant, but it’s too early at this point to tell.

More important for our purposes here, however, is the broader point this example underscores…

Quiet Creativity

When I talk about my purposefully disconnected life, a common retort is that I’m missing out on the creative possibilities born of the frequent exposure to new people and ideas delivered through social media and related technologies.

But here’s the thing, for the most part, this is not how high-level creative work is accomplished. It’s not, in other words, lack of input that stymies creative breakthroughs.

Take my own example: I don’t use Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus, Linked In, Tumblr or Instagram, and I’m bad about e-mail, but I still have no shortage of ideas to work on.

(This is not surprising, even without these technologies, I’m still significantly more connected than most scientists and writers in most other times — and they had no problem coming up with big ideas.)

What does stands in the way of creative breakthroughs — I’m increasingly convinced — is lack of time spent walking quietly with your thoughts, working and re-working your understanding of a concept in search of new layers of meaning.

This is hard deep work. But it’s also the foundation for ideas that matter.

December 29, 2013

37 Signal’s Formula for a Satisfying Career (Hint: It’s Not Passion)

Rethinking the Laborious Slog

Supporters of the passion hypothesis assume that the key to enjoying your career is choosing the right type of work.

I’ve been arguing that there are many other (and often way more important) factors that help determine whether you end up loving your career.

What you do for a living, in other words, is just a small piece in the satisfaction puzzle.

A recent Fast Company article by 37 Signal’s David Hansson (promoting his new co-authored book, REMOTE), provides a nice case study for my philosophy. Here’s Hansson:

“[T]he problem isn’t actually the work itself. It’s the fight against the hostile environment surrounding the work that’s the laborious slog…The fact is that most people like to work. Really work, that is. Engage their brain and their talents in the creation of value.”

As the article then elaborates, the “hostile environment” causing people to be unhappy with their jobs includes factors such as long commutes, requirements to live near the company offices (even if you otherwise dislike the location), and hyper-distracting office cultures.

If you can minimize these environmental negatives (i.e., by promoting remote work agreements), Hansson notes, you can significantly increase peoples’ happiness.

As career advice, “follow flexible work arrangements” sounds less sexy than “follow your passion,” but Hansson reminds us that career satisfaction is not a particularly sexy pursuit, but is instead the outcome of many careful decisions about many subtle factors.

(Photo by The Other Dan)

December 21, 2013

Deep Habits: The Importance of Planning Every Minute of Your Work Day

Time Blocking

The image above shows my plan for a random Wednesday earlier this month. My plan was captured on a single sheet of 24 pound paper in a Black n’ Red twin wire notebook. This page is divided into two columns. In the left column, I dedicated two lines to each hour of the day and then divided that time into blocks labeled with specific assignments. In the right column, I add explanatory notes for these blocks where needed.

Notice that I leave some extra room next to my time blocks. This allows me to make corrections as needed if the day unfolds in an unexpected way:

I call this planning method time blocking. I take time blocking seriously, dedicating ten to twenty minutes every evening to building my schedule for the next day. During this planning process I consult my task lists and calendars, as well as my weekly and quarterly planning notes. My goal is to make sure progress is being made on the right things at the right pace for the relevant deadlines.

This type of planning, to me, is like a chess game, with blocks of work getting spread and sorted in such a way that projects big and small all seem to click into completion with (just enough) time to spare.

Three Concerns

Sometimes people ask why I bother with such a detailed level of planning. My answer is simple: it generates a massive amount of productivity. A 40 hour time-blocked work week, I estimate, produces the same amount of output as a 60+ hour work week pursued without structure.

Sometimes people ask how time blocking can work for reactive work, where you cannot tell in advance what obligations will enter your life on a given day. My answer is again simple: periods of open-ended reactivity can be blocked off like any other type of obligation. Even if you’re blocking most of your day for reactive work, for example, the fact that you are controlling your schedule will allow you to dedicate some small blocks (perhaps at the schedule periphery) to deeper pursuits.

(Another smart strategy in this context is to give open-ended reactive blocks secondary purposes: e.g., “process client requests; if I have downtime during this block, work on project X.”)

Sometimes people ask if controlling time will stifle creativity. I understand this concern, but it’s fundamentally misguided. If you control your schedule: (1) you can ensure that you consistently dedicate time to the deep efforts that matter for creative pursuits; and (2) the stress relief that comes from this sense of organization allows you to go deeper in your creative blocks and produce more value.

If you’re still worried, read Mason Currey’s Daily Rituals: very few of the world-famous creatives he profiled adopted a “I’ll work when I feel inspired” attitude — they instead controlled their day so they could control their art.

Conclusion

In the context of work, uncontrolled time makes me uncomfortable. If you’re serious about working deeply and producing high-end value, it should probably make you uncomfortable as well. Using your inbox to drive your daily schedule might be fine for the entry-level or those content with a career of cubicle-dwelling mediocrity, but the best knowledge workers view their time like the best investors view their capital, as a resource to wield for maximum returns.

December 13, 2013

The Difficulties of Depth: A Case Study in Getting Important Things Done

Deep Tracking

I’m obsessed with deep work. I believe it’s the key to crafting a meaningful and interesting career. And yet, even I — Dr. Deep Work himself — sometimes struggle to fit enough of it into my weekly schedule.

I recently set out to find out why…

Fortunately, I have a good data set to use in this effort. As readers of STRAIGHT-A know, I believe in time blocking (if you don’t plan every minute of your day in advance, your efficiency will plummet).

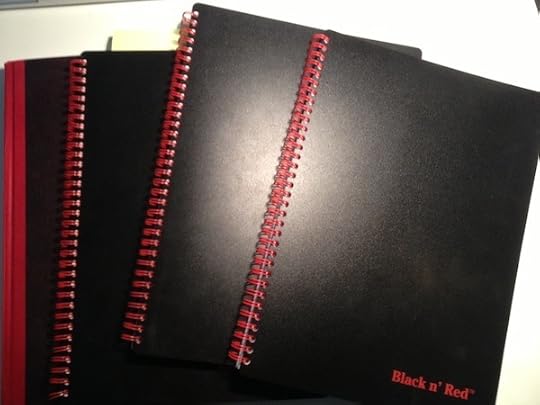

I use Black n’ Red notebooks for this purpose, one page per day. As shown in the above picture, I hold on to my old notebooks so I can study my habits when needed.

I went back through the notebook I used during my fall semester and identified two weeks: one which was good (close to half my time was dedicated to deep work on research and writing), and one which was bad (less than a quarter of my time was dedicated to these efforts).

My goal was to understand the difference between these two weeks, and by doing so, hopefully identifying the scheduling traps most damaging to efforts toward depth.

(I recognize that even my bad week represents more deep work than most are able to fit into their schedule [I've been at this for a while], but what matters here is the relative difference in time, not the absolute values.)

A Tale of Two Weeks

Let’s start with my good week. The below pie chart shows the percentage of time I dedicated to different types of work between Monday 10/21 and Friday 10/24:

Academic deep work and writing provide around half the pie — a percentage that satisfies me. Not surprisingly, class related work takes up the next largest chunk, followed by a generic planning/small tasks bucket.

Now lets look at the chart for the bad week of 11/4 to 11/7, where I fit in less than half the total amount of deep work:

What’s different about this week?

Two changes seem to matter. First, the time spent in meetings more than doubled from 3 to 7 total hours between the good and bad week. Second, I agreed to give a talk and needed to write and practice it during the bad week. This new talk prep category ate up an additional 4.5 hours. Because I cannot reduce by much the time I spend on teaching or small tasks, most of this new time came from the deep work category.

Conclusion

Here’s the worldview this experiment helped cement in my mind…

Most knowledge workers have a collection of non-optional commitments that require roughly the same amount of time each week. These are the efforts we must do to keep our job. (For me, these include teaching and keeping up with small tasks, like answering e-mails from my colleagues.)

Their remaining time is dedicated to optional commitments — which we have flexibility in selecting (and avoiding).

Here’s the key observation about this state of affairs:

Any time dedicated to deep work will come from the optional commitment pool. Every time you say “yes,” therefore, you’re also saying “no” to an equivalent amount of deep work.

In the moment, for example, it’s easy to agree to a meeting, but the hour required by that meeting is an hour drawn from the same pool used for deep work. You’ve just reduced the amount of possible deep work that week by an hour.

Once you recognize this reality, it changes the way you think about your schedule. Your criteria for saying “yes” changes from “is this something I could do and might be interesting?”, to “am I willing to give up this amount of deep work for this opportunity?”

As this experiment made clear to me, this is a subtle shift in thinking (though one that requires quite a bit of effort in execution), that can yield a massive impact on how much value you produce.

I have, accordingly, become increasingly cautious and circumspect about which optional commitments I allow into my schedule. If you’re serious about deep work, you’ll likely need to adopt a similar skepticism.

December 2, 2013

How Dirty Jobs Disrupt the Idea that Pre-Existing Passion Matters

Wisdom from Dirty Jobs

I wrote an article for the Huffington Post’s most recent installment of its TED Weekends series. The theme for this week was “A Lesson From Some of the World’s Dirtiest Jobs,” and the motivating TED talk was by Mike Rowe, former host of the Discovery Channel’s Dirty Jobs program. Many of you sent me a link to Rowe’s talk when it was first released, mainly due to the following phrase he quips about halfway through:

Follow your passion…what could possibly be wrong with that? Probably the worst advice I ever got.

His contrarian streaks seems to have struck a nerve. His talk has been viewed over 1.3 million times.

In my article, I try to explain what made Rowe’s talk so disruptive. You can read the full text at the Huffington Post, but I want to summarize here the take-away message, as I think it’s important:

In his talk, Rowe points out that many of the happiest people in the country have jobs that no one would ever identify as a pre-existing passion. He cited a sheep herder, a pig farmer (“smells like hell, but God bless him, he’s making a great living”), and a guy who makes flower pots out of cow dung, as examples of unexpected professional contentment. These observations are powerful for a simple reason: They separate career satisfaction from the specifics of the work.

We’ve heard the passion hypothesis so many times that it’s easy to accept as fact that matching the right job to a pre-existing interest is the primary source of occupational happiness. But Mike Rowe’s focus on the satisfaction found in the trades, in jobs for which no kid ever thinks, “that’s what I want to do when I grow up!”, have dealt a devastating blow to this belief.

If you’re twenty-three, in your first job out of college, not yet that good at what you do and starting to wonder if maybe this isn’t your true calling, or if you’re nineteen, and thinking about switching your college major because you don’t love every minute of every class, and worry that a “true passion” should always feel inspiring: I suggest taking an hour or two to watch some episodes of Rowe’s show.

“Roadkill picker-uppers whistle while they work,” he said at one point during his talk. “I swear to God — I did it with them.”

It only takes a few examples like the above before you begin to realize that career satisfaction is about something deeper than simply picking the right job.

November 8, 2013

E-mail Won’t Help You Win a Nobel Prize

The Elusive Dr. Higgs

This past October, the theoretical physicist Peter Higgs won the Nobel Prize for his work predicting the particle that bears his name. The only problem: no one could find him.

Peter Higgs, it turns out, is not interested in being accessible. He has no e-mail address because he owns no computer. He does own a cellphone, but he only answers it if he knows the caller.

It’s easy to imagine Higgs as a recluse, but as The Guardian reported in its Nobel coverage, he’s actually quite busy. It’s just that his definition of “busy” doesn’t include an inbox.

I like these types of stories. They’re not useful as a direct source of advice (most of us probably need to keep our computers). But they do provide a nice reminder about the type of work that ends up changing the way we understand the world.

(Image by Gert-Martin Greuel via Wiki Commons)

October 24, 2013

What’s Holding You Back From Your Creative Potential? You Don’t Work Nearly Hard Enough.

Daily Depth

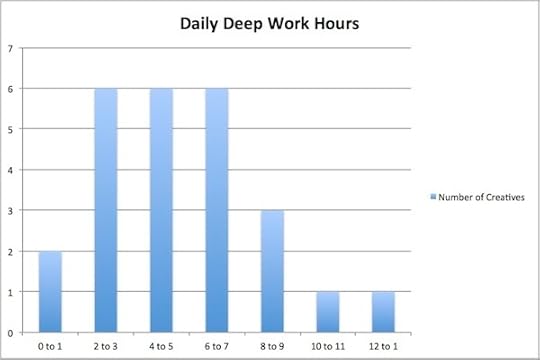

I recently got my hands on a copy of Mason Currey’s new book, Daily Rituals. For the past six years, Currey ran a blog called Daily Routines that scoured interviews and biographic material to identify the work habits of famous creatives. His new book runs with that idea, summarizing the habits of 161 notables.

Being a geek, I decided to quantify some of Currey’s insights. The first thing I did was read through the first 25 profiles, estimating the number of hours per day each subject spent working deeply.

The average number of deep work hours turned out to be 5.25. (See the above histogram for the full distribution.)

These results provide a powerful counterpoint to most narratives on creative work, which tend to focus on overcoming “The Resistance” or the “naysayer within” (to quote Steven Pressfield). The reason most aspiring creatives fail, these numbers instead hint, is not due to an “internal foe” but because five hours of daily deep work is absurdly difficult!

October 3, 2013

Why I’m (Still) Not Going to Join Facebook: Four Arguments that Failed to Convince Me

Why I Never Joined Facebook

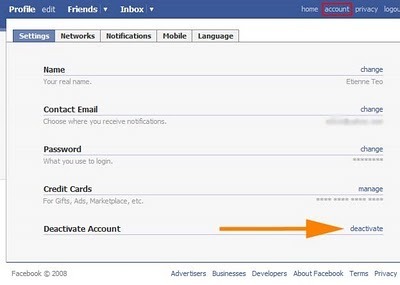

Two weeks ago, I wrote a blog post about why I never joined Facebook. For those who are new to this discussion, here’s the short summary:

I have limited time and attention. I try to devote as much of it as possible to creating valuable things and spending time with my family and close friends. For a new tool to claim some of my time and attention from these activities it has to offer me a lot of value in return. Facebook falls well short of this threshold.

This post generated a lively debate in its comment thread. To be honest, this comments discussion is probably more valuable than the original post, as it covers a lot more ground, often quite eloquently.

A natural follow-up question, however, is whether this discussion changed my mind on the issue. The short answer: No. Not at all.

To provide a longer answer, I summarize below the four most common arguments in favor of Facebook that I received in reaction to my post (both publicly and privately), as well as my explanation for why the arguments didn’t move me closer to clicking “join.”

Argument #1: Facebook makes it possible to maintain lightweight, high-frequency contact with a large number of people spread around the world.

Facebook essentially invented this new type of social connection. Some people enjoy it. Some even use it as a replacement for a normal, in-person social life (usually, to their detriment). I have no interest in it. I’m close to my family and have good friends. I’d rather keep my time and attention focused on interacting deeply with them instead of pinging a thousand “friends” with exclamation-point laden wall posts.

Argument #2: Facebook might offer you personal or professional benefits that you don’t even know about. You cannot reject this service until you have tried it for a while.

I hear this argument a lot. I find it to be an incoherent approach to managing the tools in your life. If I had to test every potentially useful tool before deciding not to use it, I would end up spending the bulk of my life testing. My time and attention is valuable. If some company wants to make money off me using their service, they better have a compelling pitch for why it’s worth me taking away time and attention from my work, family and friends — even if just temporarily.

Argument #3: Facebook will not take your time and attention away from things you currently find important because you can access it on your phone during times, like waiting in line, that would otherwise be wasted.

This vision of Facebook use terrifies me. Facebook, like most social media, is addictive, because it offers, at all points, the possibility of finding out something that someone is saying about you. Once you get into the habit of seeking this distraction when temporarily bored, your ability to concentrate during other times will be reduced. If I start checking Facebook during my downtime, in other words, I’m convinced that the overall quality and quantity of time I can spend doing hard things — like writing or solving proofs — will, rather quickly, begin to decrease.

Furthermore, the idea that you can restrict your access to this addictive service to only downtime is naive. Think about the behavior of people you know: Facebook checking soon pervades all areas of your life, including those times when, in a pre-Facebook era, you would be interacting with family or friends. “You can access Facebook anywhere!”, in other words, is not the right way to persuade me.

Argument #4: Your general philosophy of only adopting a tool if it provides a clear and valuable benefit will deprive you of serendipity — think about all the interesting things you might be missing out on.

My careful approach to tool adoption almost definitely means I’m missing out on opportunities, trends, connections, and entertainment.

This doesn’t bother me.

As a consequence of my approach to tools, I have few electronic inboxes to monitor or online services to fiddle with. This means I spend a surprising fraction of my work day actually doing hard work, leading to a professional life that is fulfilling and, to date, pretty successful (knock on wood). It also means that when I arrive home in the evening, I don’t touch a computer until the next morning — allowing me to spend my time focused on my family and friends, and giving my full attention to any number of things I already enjoy, like reading. (I read a lot.) I would be a fool to dilute this to chase the possibility of something “new.”

Fear of missing out, in other words, is not a valid argument for trashing what you already have.

#####

On an unrelated note: My friend Todd Henry (of The Accidental Creative fame) recently published a new book, Die Empty. Here’s the blurb I wrote for the jacket: “Die Empty looks past simple slogans to highlight detailed strategies for building a meaningful life; a must-read for anyone interested in moving from inspiration to action.” If you’re interested in these questions of work, meaning, and legacy, I encourage you to find out more…

September 18, 2013

Why I Never Joined Facebook

Facebook Arrives

I remember when I first heard about Facebook. I was an undergraduate at Dartmouth College. At the time, the service was being made available on a school-by-school basis, and, one spring day in 2004, it finally arrived at our corner of the Ivy League.

Many of my friends were excited by this event. They were surprised when I didn’t join.

“What problem do I have that this solves?”, I asked.

No one could answer.

They would, instead, talk about new features it made available, like being able to reconnect with people from high school or post photos. But my lack of ability to connect with old classmates or to publicize my social outings were not problems I needed fixed.

“Every product and service ever invented offers new features,” I’d respond, “but what problem do I have that Facebook’s features are solving? Why should this product, of all products, earn my attention?”

Again, no one could answer.

After a while, I stopped asking this question, and just moved on with my life without a presence on Facebook. Ten years later, I still have never had a Facebook account — nor any social media account, for that matter — and have never missed it.

I have close friends. I still have lots of readers and still sell lots of books. And I’ve preserved my ability to focus, allowing me to make a nice a living as a theoretician.

A Personal Philosophy for Adopting Tools

This brings me to a broader point: in an age of personal technological revolution, we all need a more explicit philosophy for adopting tools. Without this clarity, we run the risk of drowning in a sea of distracting apps and shiny web sites.

My philosophy — to only adopt tools that solve a major pre-existing problem — has served me well.

I use e-mail, for example, because the ability to communicate asynchronously with people around the world is quite important for my work. E-mail solves this problem.

I don’t use Twitter, however, because the ability to have short, casual interactions with many people I don’t know well is not that important to my work.

And so on.

If you adopt this particular philosophy — which I recommend — you’re effectively raising the bar when it comes to what you tools you adopt. Just because a product or service offers some new feature should not be enough for it to demand your time and attention. Save this scarce resource for tools that make a strong case for how they solve real problems you already have. Make Silicon Valley earn your interest, not take it for granted.

Or not. This is just one way of looking at a complicated problem. I am, of course, eager to hear your disagreement: please post any complaints on your Facebook wall.

September 11, 2013

Seeking Examples of Focus

Finding the Focused Few

I’m looking for stories of people who use radical strategies to reduce the amount of distractions in their life and improve their ability to focus on hard things (be it at work, at home, or in parenting).

If this describes you, someone you know, or someone you read about: please consider sending a brief e-mail to tips@calnewport.com to tell me more.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers