Cal Newport's Blog, page 48

October 26, 2014

On the Obsessive Focus of Bill Gates

The Gates Riddle

Why was Bill Gates so successful?

In answering this question, different biographers have emphasized different traits.

Stephen Manes, in his excellent 1994 book, Gates, underscores the Microsoft founder’s fierce (sometimes bordering on sociopathic) competitive instincts.

In his 2008 bestseller, Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell points out the exceptional circumstances that provided teenage Gates near unlimited access to computers on which to hone programming skills on the eve of the personal computer revolution.

I was particularly struck, however, by a quintessential Gatesian trait highlighted in Walter Isaacson’s new book, The Innovators.

Here’s a quote from the chapter where Bill Gates and Paul Allen are working on the project (a BASIC interpreter for the Intel 8080) that will give rise to Microsoft:

One trait that differentiated [Gates and Allen] was focus. Allen’s mind would flit between many ideas and passions, but Gates was a serial obsessor.

“Where I was curious to study everything in sight, Bill would focus on one task at a time with total discipline,” said Allen. “You could see it when he programmed. He would sit with a marker clenched in his mouth, tapping his feet and rocking; impervious to distraction.” [emphasis mine]

Enough said.

#####

(The above quote comes from minute 10 of Chapter 6 of Part 2 of the Audible audio version of The Innovators.)

October 22, 2014

Deep Habits: Create an Idea Index

Brain Picking

I’m a professional non-fiction writer which makes me by default also a professional reader of sorts (the photo above shows my nightstand). I read (most of) five to ten books per month on average in addition to quite a few articles.

One thing that has often frustrated me in this undertaking is the inefficiency of my notetaking. My standard strategy when reading a physical book is to mark interesting passages with a pencil and then put a check on the upper right corner so I can later skip quickly past non-annotated pages.

The problem with this strategy is that if time passes after I read a book the only way to recreate what I learned or find a useful quote is to skim through all the marked pages.

This is why I was excited the other day to learn a better way.

The Idea Index

The source of this insight was an interview on the Tim Ferris Show with Brain Pickings’s Maria Popova, who is one of the world’s most prolific readers (fifteen books per week!?) and hardest working bloggers (three long posts per day!?).

Around thirty-one minutes into the interview, Popova explains how she takes notes on books:

As she reads, she creates an index at the front of the book that lists its most interesting ideas.

Every time she encounters a passage relevant to one of these ideas she adds the page to the relevant line in the index. If its a new idea, she creates a new line for it.

As she reads more, the index grows.

Here’s what’s great about this idea index method: When you pick up a book read long ago, you can quickly recall what it has to offer by glancing at the index. Then, if you want to grab some quotes about one of these ideas, the index tells you exactly where to look (no more reading every annotation!).

I haven’t had a chance to try this habit yet, but I look forward to deploying it the next time I dive into an idea-dense title.

October 15, 2014

How to Win a Nobel Prize: Notes from Richard Hamming’s Talk on Doing Great Research

You and Your Research

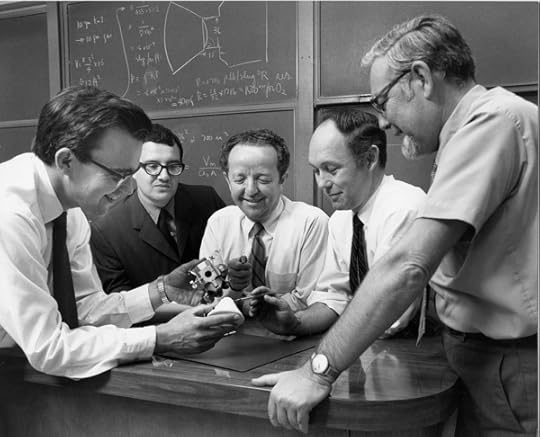

In March 1986, the famed mathematician and computer scientist Richard Hamming returned to his former employer, Bell Labs, to give a talk at the Bell Communications Research Colloquia Series. His talk was titled “You and Your Research,” and it’s goal was straightforward: to deliver lessons for serious researchers about how to do “Nobel-Prize type of work” (a topic familiar to Hamming given the large number of Nobels won by his colleagues during his Bell Labs tenure).

This talk is famous among applied mathematicians and computer scientists because of its relentlessly honest and detailed dissection of how stars in these fields become stars — a designation that certainly applies to Hamming, who not only won the Turing Prize for his work on coding theory, but ended up with an IEEE prize named after him: the Richard W Hamming Medal.

A problem with his talk, however, is it’s length and density. It’s easy to lose yourself in its transcript, nodding your head again and again in agreement, then coming out the other side unable to keep track of all the ideas Hamming outlined.

My goal in this blog post to help bring some order to this state of affairs. Below I’ve summarized what I find to be the major points from Hamming’s address. To identify the sections of the speech that correspond to each point I use the wording from this transcription.

I can’t claim that the following is comprehensive (among other things, I do not annotate the questions after the talk), but I’m confident that I capture most of what’s important in this seminal seminar.

Idea #1: Luck is not as important as people think.

[location: see the section that starts with the sentence "let me start not logically, but psychologically..."]

Hamming notes that luck is a common explanation for doing great research. He doubts this explanation by noting that great researchers — like Einstein — do multiple good things in their career.

As an alternate explanation, he cites the following Newton quote: “If others would think as hard as I did, then they would get similar results.”

Idea #2: Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest

[location: "Now for the matter of drive."]

Hamming notes that “most great scientists have tremendous drive.” He emphasizes the value of working hard by noting that the benefits of extra effort compound over time like interest. If you’re reading a little bit more and thinking a little bit longer than your colleagues, over time the gap between you and them grows.

He then supplies, however, a crucial caveat: you have to apply this effort intelligently. “That’s the trouble,” he elaborates, “drive, misapplied, doesn’t get you anywhere.” He illustrates this axiom by discussing former colleagues who worked harder than he did but have nothing to show for it.

Idea #3: Become comfortable with ambiguity

[location: "there's another trait on the side which I want to talk about..."]

Hamming notes that great scientists form an “emotional commitment” to the theories they pursue and are able to carry on despite doubts and identified flaws.

He adds, however, that they are still careful about tracking and later addressing these shortcomings that arise along the way.

Idea #4: Creativity requires focus

[location: "Now again, emotional commitment is not enough..."]

Hamming notes his belief in the theory that “creativity comes out of your subconscious.” To make a breakthrough, he believes, you must focus without distraction on the problem long enough for your subconscious to start working it over.

As he summarizes: “If you’re deeply immersed and committed to a topic, day after day after day, your subconscious has nothing to do but work on your problem.”

Idea #5: Important work comes from important problems

[location: "Now Alan Chynoweth mention that I used to eat..."]

After talking about his efforts to seek out big thinkers in the Bell Labs cafeteria, Hamming emphasizes: “If you do not work on an important problem, it’s unlikely you’ll do important work.” He notes that the “average scientist” does not work on important problems but instead plays it safe. He wanted to avoid such mediocrity in his interactions.

He clarifies that for a problem to be important, not only most its impact be clear, but you must also possess a “reasonable attack.” He estimates that most great scientists will keep 10 to 20 great problems in mind at any one time, and if they learn a technique that might apply to one of them, they’ll “drop all the other things and get after it.”

Hamming recalls that he blocked off his Friday afternoons as “Great Thoughts Time,” and spent them only discussing and thinking about “great thoughts.”

Idea #6: Keep your door open

[location: "Another trait, it took me a while..."]

Hamming notes that at Bell Labs the scientists who kept their doors shut got more done in the short term. By contrast, the scientists who kept their doors open were distracted more often but ultimately this increased exposure to other people, problems, and ideas led them to more important work in the long term.

Idea #7: Transform isolated problems into general problems

[location: "I want to talk on another topic..."]

Hamming notes that early on he used to work on isolated problems. This depressed him: “I could see life being a long sequence of one problem after another after another.”

This changed his approach to focus on bigger, more general ideas that others could build on. “By changing a problem slightly” he clarifies, “you can often do great work rather than merely good work.”

He goes on to add that you should never work on an isolated problem unless it is “characteristic of a class.”

Ideas #8: Sell you results

[location: "I have now come down to a topic which is..."]

Hamming notes that the idea of marketing your results is “distasteful” and “awkward” to discuss. He also notes, however, that it’s necessary because “the fact is everyone is busy with their own work,” and you cannot expect them to discover your work on their own.

He suggests three things you must do to bring you ideas to other peoples’ attention: (a) “learn to write clearly,” (b) “learn to give reasonably formal talks,” and (c) “learn to give informal talks” (and know which type of talk is appropriate and when.)

He emphasizes that when giving a talk, in most venues, “most of the time the audience wants a broad general talk and wants much more survey and background than the speaker is willing to give. As a result, many talks are ineffective.”

October 8, 2014

Deep Habits: Conquer Hard Tasks With Concentration Circuits

A Writing Tour of Georgetown

Today I needed to finish a tough chunk of writing. The ideas were complicated and I wasn’t quite sure how best to untangle the relevant threads and reweave them into something appealing. I knew I was in for some deep work and I was worried about my ability to see it through to the end.

So I packed up my laptop and headed outside. Here’s where I started writing:

Once I began to falter, I switched locations:

As I neared the end my energy begin sputter, so I switched locations one more time for the home stretch:

In this third and final location I finished.

The Concentration Circuit

Combined, the chunk of writing took me two hours: less time than I had expected. The key to this efficiency, I’m convinced, was the frequent location switching.

Something about arriving at a new and novel location — somewhere different than where you normally work — provides a boost to your motivation and aids concentration. Over time, this effect will wane. But if you keep switching locations, you can keep re-stimulating this reaction again and again, maintaining an average level of concentration that’s potentially much higher than if you had slogged through the deep task in one (literal) sitting.

I call this approach the concentration circuit as it cycles you through a circuit of locations to keep your concentration levels elevated.

To be clear, most of my deep work sessions are decidedly less interesting. They take place in my office with the door closed.

But sometimes I need something extra. If I’m feeling uninspired or the task is particularly complicated, I look for ways to scrape together any advantage I can find (c.f., here and here and here). The concentration circuit is an important tool in this deep work toolbox.

October 3, 2014

How We Sent a Man to the Moon Without E-mail and Why it Matters Today

The NASA Paradox

In 2008, Dan Markovitz was meeting with a group of R&D engineers at a high tech company. The engineers began complaining about e-mail.

They were overwhelmed by the hundreds of messages arriving every day in their inbox, but at the same time, they agreed that this was unavoidable. Without such intensive e-mail use, they reasoned, their teams’ efficiency would plummet.

This conclusion led one of the engineers to ask an interesting question:

If this is true, “how [did] NASA’s engineers manag[e] to put a man on the moon without tools like email?”

Think about this question for a moment. The Apollo program was massive in size and complexity. It was executed at an incredible pace (only eight years spanned Kennedy’s pledge to Armstrong’s steps) and it yielded innovations at a staggering rate.

And it was all done without e-mail.

How did the Apollo engineering teams manage something so complicated and large without rapid communication? Fortunately for this particular group, an answer was available. It turned out that a senior engineer at this high tech company had also worked on the Apollo program, and someone asked him this very question.

Here’s how the Apollo engineer remembered working:

His team met from 9 – 10 am, three days per week.

They spent the rest of their time “actually working on solving this enormous puzzle of landing on the moon.”

If someone got stuck and needed someone else’s input, “they actually talked to each other.”

To quote Intel engineer Nathan Zeldes (as Markovitz does in summarizing this approach):

“These guys were plan-driven, not interrupt-driven.”

I find this anecdote fascinating. I’m not implying, of course, that organizations should abandon e-mail altogether and fall back on Apollo-era carbon copies and secretary pools.

But hearing this story induces a key insight: the way we currently use e-mail technology — in which our day is interrupt-driven and quick responses are expected — is not a necessary condition to successfully manage teams and organizations tackling hard problems.

If you’ll excuse some uninformed speculation, my guess is that if we could go back in time and outfit the Apollo engineers with e-mail terminals,* two things would have happened. First, their work lives would have become more convenient. Second, it would have taken them longer to get a man on the moon.

Or maybe not.

But at the very least, we should use this story to remind ourselves that the statement, “I have to be constantly connected to effectively manage my team/company/project,” is not a tautology; it’s a hypothesis — one we can and should continue to rigorously investigate.

#####

* Let’s be honest, if we went back in time to give these engineers e-mail terminals, the first thing they would do is pry open the cases and hijack the processors to replace the creaky technologies they were stuck using (the Apollo guidance computer ran at a stately 1 Mhz and had all of 2k of memory to work with).

October 1, 2014

Deep Habits: Don’t Web Surf During the Work Day

Swimming to the Offline Shore

By 2004, I was an expert web surfer. I had memorized a sequence of web site addresses that I could cycle through, one after another, in rapid succession. I would do this once every hour or so as a quick mental pick me up to help get through the work day.

At some point, soon after starting graduate school at MIT, I dropped the habit altogether. It’s been close to a decade since I considered the web as a source of entertainment during my work day.

Indeed, I’m so out of practice with web surfing, that I’ve found on the few occasions that I’ve recently tried to relieve some boredom online, I wasn’t really sure where to go or what to do. (Most of the articles I end up reading online are sent to me directly by readers, not encountered in serendipitous surfing.)

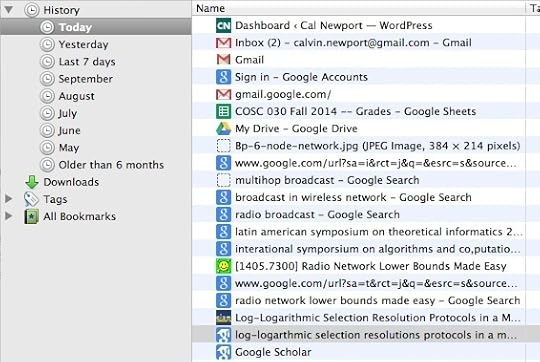

To illustrate this point, the image at the top of this post is a screenshot of my complete browser history for today, taken at 2 PM. (Note: I doctored the list slightly to remove redundant entries for a given visit to a given site.)

A Replicable Feat

Imagine what would happen to your efficiency and depth if you dropped all non-work related web use during your work day.

No clickbait. No Facebook. No blogs (except, of course, Study Hacks, which is immensely relevant to everyones’ professional success!) From my experience, the impact of such work day prohibitions is massively positive.

When you eliminate the chance of web surfing, you tend to be more efficient in processing your work. (The way I see it is that I’d rather finish my day an hour early than sprinkle an hour of time wasting throughout.)

Of equal importance, the simplicity of the rule — no web surfing, no exceptions — makes it easy to avoid this temptation when trying to work deeply, thus preventing unnecessary ego depletion.

Some might worry about the need to be in the loop. At least for me, however, this has never been an issue. As the computer scientist Don Knuth put it: “[Frequent connectivity] is a wonderful thing for people whose role in life is to be on top of things. But not for me; my role is to be on the bottom of things.”

To conclude, we’ve become so enmeshed in the attention economy that it can seem impossible to fathom leaving it for a large part of your day. But this is why I’m telling you my story.

It is hard at first.

But after a while, you don’t miss it.

September 26, 2014

Should You Work Like Maya Angelou or Eric Schmidt?

A Focused Digression

David Brooks’s most recent column ends up on the subject of geopolitics, but it begins, in a tenuous but entertaining fashion, with a long digression on the routines of famous creatives (which Brooks draws from Mason Currey). For example…

David Brooks’s most recent column ends up on the subject of geopolitics, but it begins, in a tenuous but entertaining fashion, with a long digression on the routines of famous creatives (which Brooks draws from Mason Currey). For example…

Maya Angelou , we learn, was up by 5:30 and writing by 6:30 in a small hotel room she kept just for this purpose.

John Cheever would write every day in the storage unit of his apartment. (In his boxer shorts, it turns out.)

Anthony Trollope would write 250 words every 15 minutes for two and a half hours while his servant brought coffee at precise times.

To summarize these observations, Brooks quotes Henry Miller: “I know that to sustain these true moments of insight, one has to be highly disciplined, lead a disciplined life.”

He then offers his own more bluntly accurate summary: “[Great creative minds] think like artists but work like accountants.”

Or, to put it in Study Hacks lingo: “deep insight requires a disciplined commitment to deep work.”

Keeping these insights in mind, now consider the following article posted on Time.com the day before Brooks’s column: 9 Rules for Emailing From Google Exec Eric Schmidt.

The piece offers an excerpt from Schmidt’s new co-authored book, How Google Works. Here’s the first piece of advice it offers:

“1. Respond Quickly. There are people who can be relied upon to respond promptly to emails, and those who can’t. Strive to be one of the former. Most of the best—and busiest—people we know act quickly on their emails.”

This juxtaposition represents a trend that puzzles me.

We know, as Brooks observed, that brilliant creative work requires repeated long periods of uninterrupted depth.

We hear often that brilliant creative work is incredibly valuable in our current business culture.

And yet this same culture ignores depth and continues to glorify connectivity (as Schmidt exemplifies).

(Some might argue that you can do both, spending most of your time responding quickly to communication, then carving out additional time to go deep when needed: but the research shows our mind doesn’t work that way; and most people probably intuitively understand this.)

To explain this trend, it might just be the case that in business, the impact of constant connectivity on one’s marginal productivity outpaces the impact of deep work.

But at the same time, if one is feeling a bit cynical, it might seem like a lot of this preference for connection over depth is due to the fact that although the Eric Schmidts of the world like the idea of creative insights, in the moment they like even more the convenience of getting a quick response to their messages.

And I would suspect that Maya Angelou was probably terrible at e-mail.

September 24, 2014

Deep Habits: Use Dashes to Optimize Creative Output

Obsessing About Selection

I’m currently trying to solve a fun problem that’s captured my attention and refuses to relent. Here’s the basic setup:

A collection of k devices arrive at a shared channel. Each device has a message to send.

Time proceeds in synchronized rounds. If more than one device tries to send a message on the channel during the same round, there’s a collision and all devices receive a collision notification instead of a message.

The devices do not know k.

In this setup, a classic problem (sometimes called k-selection) is devising a distributed algorithm that allows all k devices to successfully broadcast in a minimum number of rounds. The best known randomized solutions to this problem require a*k rounds (plus some lower order factors), for a small constant a > 2.

What I am trying to show is that such a constant is necessary. That is: all distributed algorithms require at least b*k rounds for some constant b bounded away from 1 (and hopefully close to 2).

The Dash Method

What I’ve noticed in my thinking about this problem over the past week or two is that at the beginning of each deep work session, I’ll typically come up with a novel approach to attempt. As I persist in the session, however, the rate of novelty decreases. After thirty minutes or so of work I tend to devolve into a cycle where I’m rehashing the same old ideas again and again.

I’m starting to wonder, therefore, if this specific type of deep work, where you’re trying to find a creative insight needed to unlock a problem, is best served by multiple small dashes of deep work as oppose to a small number of longer sessions.

That is, given five free hours during a given week, it might be better to do ten 30-minute dashes as oppose to one 5 hour slog.

My Experiment

So I’m going to try this. For the next week or so, I am going to limit my thinking on this problem to under 30 minutes at a stretch, and try to sprinkle such dashes throughout my week.

Of course, if I make a breakthrough in one of these sessions, I will then default to the more standard long stretches required to work through the tricky details of any such proof. (In other words, I want to make clear that the brevity I am pitching in the dash method is really only well-suited to this quite specific type of work.)

I must admit that I approach this technique with some trepidation. My main concern is that once the dash gets too short I’ll start to leverage the impending termination to excuse my tendency to sidestep the annoying math that is sometimes necessary to verify whether or not an idea works. (My mind much prefers “eureka solutions” in which the applicability is self-evident, to the point where it will sometimes ignore potentially good but hard solutions in hopes of a eureka lurking around the neuronal corner.)

We’ll see.

In the meantime, if you have a solution to the above problem, let me know.

(Photo by Kacper Gunia)

September 17, 2014

How the Best Young Professors Research (and Why it Matters to You)

Lounging in Lauinger

Lounging in Lauinger

Today I spent the morning in the library. As often happens, I arrived with a specific book in mind, but soon a long trail of diverting citations lured me in new directions.

I’m a sucker for libraries.

One such happy discovery was the book, The New Faculty Member, by Robert Boice, a now emeritus professor of psychology at Stony Brook. This book summarizes the findings of a multi-year longitudinal study in which Boice followed multiple cohorts of junior professors, at multiple types of higher education institutions, from their arrival on campus until their tenure fate seemed clear.

(He also wrote a non-academic version of this book called Advice for New Faculty Members, which I haven’t read, but assume is similar in its conclusions.)

I was particularly drawn to his chapter on research productivity. It turns out that Boice hounded his subjects on this topic year after year. He didn’t trust self-estimates of work accomplished and instead required the young professors to produce newly written pages to verify progress.

After four years, only 13% of these professors had produced enough (and had good enough teaching evaluations) to make tenure seem highly probable. Here are some of the main differences Boice identified in the research habits of these “exemplary young faculty” as compared to their peers:

The exemplary faculty did not wait for “ideal” times to write.

As Boice explains: “waiting for ideal times such as binges induces more than mere uninvolvement…[i]t can also bring procrastination and dissatisfaction.”

The exemplary faculty instead maintained a regular writing habit.

As Boice explains: “[they] pay close attention to regiment…[those who] did not establish a regiment of writing regularly did not establish productivity.”

The exemplary faculty put thought into how to be more productive.

As Boice explains: “[new faculty] would do well to take more notice of knowledge, usually untaught in open systematic ways, about survival, including self-management.”

The exemplary faculty looked for outside help in improving their academic productivity.

As Boice explains: “The quick starters depicted here, unlike their counterparts, were proactive in soliciting collegial advice. They were quick to dismiss the idea that they had to figure out the subtle rules of productivity on their own.”

The advice in this short but dense guide is undoubtedly useful to people like me who are young professors hoping to inch into the exemplary category. But I noticed that Boice talked a lot about how his subjects struggled with both the autonomy and loneliness of their position — in which much is expected but little guidance is provided.

These seem like obstacles common to many entrepreneurial endeavors, which leads me to speculate that many of Boice’s findings should resonate well beyond the Ivory Tower. Put another way: if you replace above the word “write” with whatever verb captures the core value producing activity in your own entrepreneurial endeavor, Boice’s findings will likely seem suddenly quite relevant.

September 13, 2014

Deep Habits: Jumpstart Your Concentration with a Depth Ritual

In Search of Depth

Aaron is a PhD student. This requires him to spend a significant fraction of his time thinking about hard things.

To accommodate the necessity of depth in his working life, Aaron developed a ritual he uses to quickly shift his brain into a state of concentration.

Here’s how it works:

Aaron puts on headphones and plays non-distracting meditative music (this track is a favorite).

He launches FocusWriter, a stripped-down text editor that hides all the features of your computer (not unlike George R. R. Martin’s use of Word Star).

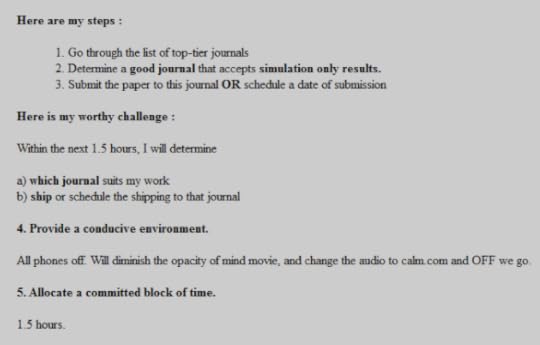

He loads up a template that contains seven questions about the deep task he’s about to begin. These questions force him to specify why the task is important and how he’s going to tackle it (see the above screenshot of the template taken from one of Aaron’s work sessions). The issues addressed in this template come from a classic Steve Pavlina post titled “7 Ways to Maximize Your Creative Output.”

Getting through these steps takes around five minutes. As soon as Aaron’s done typing in his final answer he turns immediately to the scheduled deep task.

The Results of Ritual

Here’s how Aaron describes the impact of this ritual:

“Every time I have done this (well, nearly every time) I [entered] a deep thinking phase quite effortlessly. I think the reason why it works is that the barrier to entry is quite small (filling out the template) and the returns (clarity on session objective, momentum) are tangible.”

Aaron (not his real name) sent me a note about these habits only recently, but the idea of a depth ritual is one that I’m encountering more frequently as I continue my research into the topic of deep work.

I don’t know exactly why such rituals work but it doesn’t surprise me that they do.

Achieving unbroken concentration is not like flossing — an action you can just choose to do — it’s instead a mindset: and a non-natural one at that! To slip into a state of depth, we need all the help we can get.

The Need for Ritual

Which brings me to my own habits. I don’t currently deploy a depth ritual, but I’m increasingly convinced that such a commitment would benefit me greatly.

Indeed, with this in mind, I experimentally deployed Aaron’s specific set of steps before I wrote the blog post you’re currently reading.

It’s now exactly 29 minutes since I turned on my computer, and I’m now about to hit publish on this piece which I wrote, formatted (including imaging processing), and edited from scratch all during this single session.

For me, these results are, for lack of a better word, deeply impressive.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers