Cal Newport's Blog, page 46

February 26, 2015

Compelling Career Advice from Barack Obama

A Compelling Answer

Earlier today, a reader pointed me toward a blog post about Barack Obama from the Humans of New York project. The post quotes Obama’s answer to the following question: When is the time you felt most broken?

The president begins his response by recalling a doubt-ridden plateau in his political career…

“I first ran for Congress in 1999, and I got beat. I just got whooped…for me to run and lose that bad, I was thinking maybe this isn’t what I was cut out to do.”

What caught my attention (and the attention of the reader who forwarded me the interview) is the idea Obama leveraged to move forward…

“But the thing that got me through that moment, and any other time that I’ve felt stuck, is to remind myself that it’s about the work. Because if you’re worrying about yourself — if you’re thinking: ‘Am I succeeding? Am I in the right position? Am I being appreciated?’ — then you’re going to end up feeling frustrated and stuck. But if you can keep it about the work, you’ll always have a path. There’s always something to be done.”

In SO GOOD, I called this the craftsman mindset. It asks that you stop obsessing about what the world can offer you, and instead focus on what you can offer the world.

Notice, this mindset is often at odds with the popular advice to “follow your passion.” Barack Obama was probably not feeling a lot of passion for politics after his loss to Bobby Rush. But he thought he had something to offer in this arena, so he persisted. (See my recent Business Insider article on Steve Jobs for another example of this mindset at work.)

The power of this advice, however, is probably best summed up by the note that the reader who sent me this article appended to the message.

“I respect this a lot about Obama,” he wrote, before admitting, “and, I’m a Republican.”

(Quote and image from Humans of New York.)

February 23, 2015

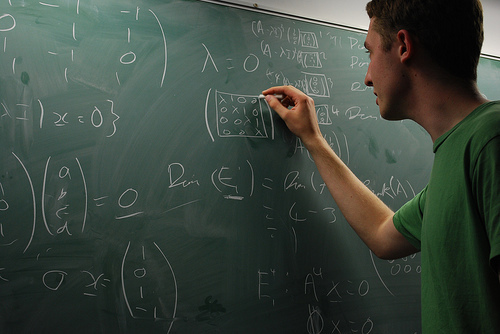

Deep Habits: Work With Your Whole Brain

Surprising Understanding

Last summer, I wrote a post detailing various strategies for reading mathematical proofs faster.

Last week, I stumbled across a new strategy that I think may be relevant for many different types of deep information processing.

I came across this strategy while peer reviewing a complicated computer science paper. As I read, I quickly became frustrated. I was processing lemmas and theorems, one by one, but as the details for each slipped from my short term memory to make room for the next, there was no sense of a coherent whole. It was as if I couldn’t get my metaphorical arms around this mathematical beast.

After an hour of this blind processing I decided to step back and try to summarize what I understood so far.

It was here that things got interesting.

As I wrote, I discovered to my surprise that I actually understood way more than I expected. My short summary stretched into a longer digression on the problem, why it was hard, what their technique did differently than previous results, and, in the final accounting, where the real contributions could be found.

To be clear, I didn’t have the math all worked out. If you asked me to recreate all the proof details, I couldn’t. But somehow during my frustrated slog from one step to the next, another part of my mind was dutifully collecting and organizing the pieces — work which didn’t become apparent until I tried to write down what I knew.

New Thoughts on Thoughts

Not long ago, when researching a yet to be announced new writing project, I stumbled into a large research literature on what is sometimes called Unconscious Thought Theory (UTT). At the core of UTT is the following idea: the parts of our brain supporting conscious thought represent only a small fraction of our neuronal horsepower. When it comes to complex tasks, therefore, our conscious attention can help intake and understand only a limited amount of information at a time.

Other parts of our brain, however, that operate below the level of conscious attention, are able to dedicate a lot more resources to processing these tasks: even though we don’t always realize this is going on.

I suspect this is what was happening during my paper review. While reading the paper, my conscious mind could only hold a limited amount of the complex information in my working memory at any given moment. The result was the frustrating feeling that I didn’t understand how the pieces fit together.

In the background, however, other parts of my brain were processing this information, trying different configurations and looking for effective ways to fit things together into a more coherent assembly.

When I then tasked myself with summarizing what I knew, my conscious brain tapped into this large reservoir of unconscious work, surprising me by how much I actually understood.

At least, this is one possible explanation.

Process then Summarize

Regardless of the exact source of the phenomenon I encountered, I suspect the strategy that generated it provides a useful deep habit for many cases where you must make sense of a large amount of complicated information.

Spend time to process the information, piece by piece, with full concentration. Once you’re done, step back and try to summarize what you learned. Though the process of digesting the information might feel frustratingly scattered, you’ll likely be surprised by how much work the other parts of your mind accomplished on your behalf. By writing down what you know, you cement this effort.

February 18, 2015

J.K. Rowling’s Magical Writing Hut and the Pursuit of True Depth

A Magical Muse

This past fall, news broke that Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling was building a replica of Hagrid’s hut near the border of a forest on her Scottish estate.

Though its intended use is unknown, Entertainment Weekly speculated Rowling might be designing the ultimate writing cabin for her current project: penning the screenplay for a Potter prequel.

This reminded me of Neal Stephenson. To set the right mood for his 17th century historical novel, Quicksilver, he wrote the manuscript longhand with a fountain pen, in a basement alcove decorated by an 18th century map of London.

Similarly, when Michael Pollan still lived in Connecticut, he wrote his books about nature in a hut (which he built by hand) in the woods beyond his backyard. On nice days, the large window facing his desk could be swung open — erasing the boundary between outside and in.

Immersive Work

I love how these authors strive to inhabit the deep work that’s made them famous, and don’t just treat their craft as another series of tasks to be checked off somewhere between sending e-mail and stopping by the store. They make work an experience, not a chore.

Perhaps this is part of why they’re so good at it?

Staring aspirationally at the photos above, it’s hard not to wonder if it’s possible to translate this emphasis on crafting the best possible environment to other knowledge work pursuits. What would the ultimate computer programming den look like? How about the optimal mathematician’s proof solving chamber?

Maybe in a future where deep work is given its due, these are questions that will have ready answers.

(Hagrid hut photo by Scott Smith)

#####

My friend Elizabeth Grace Saunders just published her new book with Harvard Business Review Press. It’s called How to Invest Your Time Like Money. Elizabeth’s systematic treatment of making decisions about what to spend time on (as oppose to the standard focus on organizing your existing commitments) has been influential to my thinking. Check out what she has to say…

February 15, 2015

This Company Eliminated E-mail…and Nothing Bad Happened

Super Casual Friday

Last week, an article in the Washington Post caught my attention. It was titled, “At some start-ups, Friday is so casual that it’s not even a work day,” and it focused on an Oregon-based tech company called Treehouse.

This company, it turns out, offers an unusual perk to its employees: no work on Friday.

The idea of a four day week upset people in the tech world. Michael Arrington, for example, responded:

“As far as I’m concerned, working 32 hours a week is a part-time job…I look for founders who are really passionate. Who want to work all the time. That shows they care about what they’re doing, and they’re going to be successful.”

But here’s the thing: Treehouse is successful.

The company, which offers online courses, has enrolled over 100,000 students and raised over $13 million in funding. Last year saw 100% revenue growth, and, perhaps not surprisingly, they have near 100% employee retention.

A Deep Paradox

At first, this might seem like a paradox: Treehouse reduced working hours yet didn’t reduce its effectiveness. The solution comes later in the article when the company’s founder explains:

“That’s the key. Do what’s important for you. Then, when you have time, respond to things…I’ve definitely worked in environments where all I did was e-mail. Now, internally, there’s almost zero. That’s a huge, huge win for the company.”

He elaborates that he’s eliminated an e-mail-centric cult of connectivity at Treehouse. Employees communicate in forums dedicated to specific projects, and the expectation that you can and should receive instant answers to your electronic missives doesn’t exist.

The solution to our above paradox, in other words, is that the eight hours cut from Treehouse employees’ weekly schedule disproportionately affected shallow efforts (namely: preserving a culture of constant e-mail connectivity). The reason their company still thrives is that the deep efforts that matter most remained unmolested.

This interpretation, if true, provides another piece of evidence for a conclusion I’ve been pitching for a while here on Study Hacks: a lot of the busyness afflicting the burnt out knowledge work class isn’t actually producing much value.

If more companies (and individuals) followed Treehouse’s lead and actually tested the conventional wisdom that all of this distracting shallowness is vital, I suspect we’d suddenly see a lot more emphasis on deep work in our cultural conversation surrounding productivity and effectiveness.

February 5, 2015

Deep Habits: Work Analog

A Curious Observation

I’ve written enough books at this point to notice trends about the process. Case in point, while many stages of pulling together a book end up going slower than expected, there’s one stage, in particular, that typically goes quicker: polishing the manuscript.

I have a theory for the phenomenon. When I polish a book manuscript, I always work with printouts and a pen (as I also advise, in Straight-A, for paper writing). Because this work doesn’t need a computer, I tend to settle in somewhere conducive to concentration, like The Chair (above), and end up working with more focus for longer sessions than normal.

The magic ingredient, I suspect, is the analog nature of the process. A computer is a portal to near endless distraction. Because we use these machines for so much of our efforts, the staccato rhythm of broken concentration they generate begins to feel natural — as if this is the necessary experience of work.

All it takes, however, is a forced break from the digital — as I experience when polishing my books — to remember the levels of depth we’re missing, and the satisfactions they can bring.

Inspired by this observation, I’ve found myself increasingly trying to carve out tasks that can be done free from a screen. I’m now more likely, for example, to venture to a library with only a notebook to work on a proof, or to leave my laptop in my bag at my office to dig into some paper reviews.

Analog work is underrated. Try it for yourself: you won’t be disappointed.

January 25, 2015

Robin Cook’s (Literal) Deep Work

Cook’s Colloquium

While I was at MIT, I lived for two years on Beacon Hill. One of my neighbors, I discovered, was the medical thriller writer, Robin Cook (to put things in perspective: I lived in a 500 square foot apartment while he lived in a six-floor, 1833 townhouse).

I didn’t run into Cook, however, until he agreed to give a speech at the Beacon Hill Civic Association. Eager to hear more about the life and times of this mega-bestselling author, I marked my calendar and attended the talk.

Cook didn’t disappoint. But there was one anecdote, in particular, that caught my attention.

Going Deep

Soon after finishing his general surgery residency, Cook was drafted into the Navy, where he ended up stationed as a ship’s doctor on the USS Kamehameha.

The Kamehameha, it turns out, is a nuclear ballistic missile submarine, which means that Cook spent much of his tour underwater, with little to do while the sub made its slow circuits. It was here, in his cramped office, that he began writing his first novel, The Year of the Intern — engaging in what I think we can agree to be some of the (literally) deepest ever sessions of deep work.

After his stint on the Kamehameha, Cook continued seeking out settings conducive to depth. He managed, through a fortuitous connections to Jacques Cousteau (a story for another time), to become involved in the Navy’s SEALAB program, where he had occasion to live for weeks, as an aquanaut, in an undersea habitat.

Each stretch in the habitat required up to 13 days in a decompression chamber after surfacing. It was here that Cook saw another, perhaps even more extreme, possibility for deep work. As he recounted at the Civic Association, he had a typewriter brought into the chamber, so that once him and his cremates were locked inside, he could pound away, making progress on his book.

This deep work training soon served Cook well. In the mid-1970’s, Cook was undergoing a second medical residency, this one in Ophthalmology at Harvard. In a period of six weeks during this residency, he worked deeply every night on a thriller he eventually titled Coma.

Once published, this book became a massive bestseller. One of the first things he purchased with the money was his historic townhouse in Beacon Hill (at the time he was renting an apartment there). The skill, in other words, that made Robin Cook my impressive neighbor was his well-practiced ability to go deep.

January 18, 2015

Deep Habits: Use Index Cards to Accelerate Important Projects

The Difficulty of Deep Projects

For the sake of discussion, let’s define a deep project to be a pursuit that leverages your expertise to generate a large amount of new value. These projects require deep work to complete, are rarely urgent and often self-initiated (e.g., no one is demanding their immediate completion), and have the potential to significantly transform or advance your professional life.

Examples of deep projects include writing a highly original book, creating an irresistible piece of software, or introducing a new academic theory.

The problem with deep projects is that they’re complicated and really hard. Almost any other activity will seem more appealing in the moment — so they keep getting pushed aside as something that you’ll “get to soon.”

Recently, I’ve been experimenting with a habit that seems to help with this challenge.

I call it, the depth deck…

The Depth Deck

The idea behind the depth deck is simple. Identify one or two deep projects that are important to your professional life.

For each project, identify one or two concrete next steps that:

require deep work;

are self-contained in the sense that they have a single focus and a clear criteria for when they’re completed.

You can vary the sizes of these steps. Perhaps some require only an hour or two of deep work, while others might require 10 to 15 hours. (If you think more time is needed, than you should probably break it down into smaller pieces.)

You can also vary between decidable and undecidable tasks. (I try to keep half my next steps decidable and half undecidable). If you select an undecidable task, however, you should integrate a time limit into your completion criteria (e.g., solve this proof or spend 15 deep hours on it: whichever comes first), as, by definition, you cannot force such efforts.

Next, record each next step on its own blank index card. Under its description — and this is important — write the date that you started it. Take this small stack of index cards, fasten them with a binder clip, and keep them with your work stuff at all times. (See the image above.)

This is your depth deck.

Now, going forward, whenever you put aside time for working on important, but non-urgent projects, focus your attention on one of the small number of steps in the deck. When you finish one of these steps, record on the card the date you finished it, add it to a completed pile, and create a new card to replace it.

Why it Works

There are three reasons why this simple habit helps counteract the difficulty of deep projects mentioned earlier.

The first reason is clarity. As mentioned, deep projects are complicated and hard, so it’s easy for them to morph into an ambiguous, overwhelming mess. This is not a state that will generate much productivity. The depth deck cuts through this murkiness and produces a small number of concrete next step that can become the target for all your ambition-driven energy.

The second reason is priority. The idea that should reduce your obligations to clear next steps is standard productivity practice. By pulling out a small number of next steps that affect projects of real significance, however, and then keeping them with you at all times in their own special deck, helps you maintain a sense of high priority for these high value pursuits, even as the rest of your time saturates in shallower minutia.

The third reason is accountability. Because you record the date in which you started on each next step, and you keep the depth deck with you, you’ll be constantly confronted with evidence about how much time you’re letting pass without taking action on something important to you. The fact that these next steps are relatively small plays an important role here. If, for example, on January 1, you added a card that said, “write a novel,” and three weeks go by without you doing much about it, this isn’t so distressing: a novel is a really big project that takes a long time. Three weeks is just a drop in the bucket for this project’s duration. On the other hand, if you have a small next step in your depth deck that reads, “write a back story on your five main characters,” and you let three weeks go by, you’ll be confronted with the reality that you couldn’t even scratch together a handful of hours for your project in the last 21 days! This is more embarrassing. Avoiding such internal embarrassment will spur your mind into action.

(A bonus benefit of this strategy is the pile of completed cards it generates. Periodically browsing these cards can provide inspiration — e.g., transform your self-image into someone who does get deep work done — as well as important knowledge — e.g., if you notice tasks of a certain type take a long time to complete, you might better schedule time for them.)

To summarize, the depth deck is a relatively minor hack. There are many others like it that might help you advance in the battle to consistently work deeply on important things. The bigger point here, therefore, is the recognition that to master the art of deep work you need to continually muster every advantage available.

January 12, 2015

Christopher Nolan Doesn’t Use E-mail (and Why This Matters to You)

The Disconnected Director

Ben Casnocha recently sent me a Hollywood Reporter interview with the director Christopher Nolan. About halfway through the transcript, the journalist asks Nolan if it’s true that he doesn’t have an e-mail address.

“It is true,” Nolan responds.

He then elaborates:

Well, I’ve never used email because I don’t find it would help me with anything I’m doing. I just couldn’t be bothered about it.

What interests me about Nolan’s answer is not the details of his technology choices (his ability to avoid e-mail is specific to his incredibly esoteric job), but instead the thought process he applied in making them.

It would be easy to list dozens of benefits that Nolan would reap if he used e-mail. But his decision process is not focused on whether the technology can offer any benefit.

He’s clearly instead mono-focused on the impact of the technology on the thing he’s trying to do better than anyone else in the world: direct successful movies.

For this goal, e-mail is largely irrelevant — so Nolan doesn’t bother. This diligent discarding of anything not substantially connected to his major professional goals, we can conjecture, goes a long way toward explaining his success.

Each year, Silicon Valley investors are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into companies whose sole purpose is to try to capture our attention long enough to sell ads. Given this onslaught of shiny digital addictiveness, we could all probably use a dose of Nolan’s sang froid response to such entreaties: if you’re not helping me become world class, then get the hell out of my way.

(Photo by Conmunity)

January 5, 2015

Deep Habits: Read a (Real) Book Slowly

A Call to Read

Maura Kelly begins her 2012 manifesto in The Atlantic with a Pollan-esque exhortation:

Read books. As often as you can. Mostly classics.

Kelly is just one voice in the growing Slow Reading movement (c.f.., here and here). The motivating idea behind this movement is simple: it’s good for the soul and the mind to regularly read — without distraction or interruption — hard books.

There was a time when intellectual engagement necessarily included long hours reading old-fashioned paper tomes. But in an age when a digital attention economy is ascendant, it’s now possible to satisfy this curiosity without ever consuming more than a couple hundred highly digested and simplified words at a time.

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with this new form of lightweight information consumption — the problem is the behaviors it tends to replace.

Reading a hard book, we must remember, is an experience that returns many rewards not generated by a pithy blog post (ahem) or online magazine.

These rewards of slow reading include (but are not limited to) the following:

It helps you sharpen your ability to work through complicated ideas.

It trains your ability to resist distraction.

It adds new layers of sophistication to your understanding of others and the world we inhabit.

It builds your comfort with ambiguity and respect for disciplined expertise — both useful traits in an increasingly polarized and unjustifiably self-confident culture.

These are all worthy goals by themselves. (And the first two, in particular, are immensely useful in cultivating a deep work habit.)

For these reasons, consider this simple resolution for your New Year: commit to regularly spending a non-trivial amount of time reading a book that strains your comprehension.

(Photo by Smilla4)

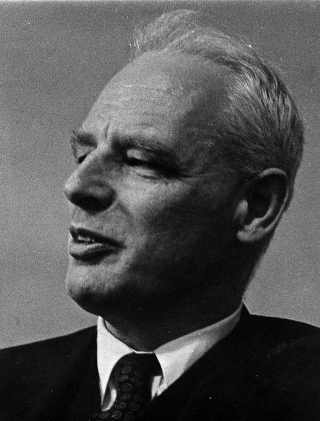

December 29, 2014

Thinking is Uncomfortable but Exciting

Thoughts on Thinking

Thoughts on Thinking

“Thinking [is] a very special type of psychic activity, very uncomfortable, but also very exciting…”

This quote comes from the influential twentieth century classicist, Eric Havelock. It’s taken from a book in which Havelock argues that the invention of writing in the ancient world was a prerequisite for the activity we now call “thinking” (he’s talking here about thought in its most rigorous form in which we embrace abstraction and attempt to understand truths beyond specific concrete encounters with the world).

What strikes me is that Havelock describes demanding cognition as both uncomfortable and exciting.

These two adjectives sum up well the sometimes complicated experience of deep work. This activity is not fun in the sense that it can cause mental strain and discomfort, but at the same time, the rewards it produces are richer than anything that the addictive digital bazaars of the attention economy can offer.

I don’t have a specific suggestion to offer here. This is just a meditation to keep in mind as we enter a season of New Year’s resolutions and begin to ask, as we do most Januarys, how we should define a working life well lived…

#####

The quote comes from pages 283 – 284 in the 2009 Harvard University Press edition of Havelock’s influential Preface to Plato. It was first brought to my attention by James Gleick’s ambitious 2011 book, The Information.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers