Cal Newport's Blog, page 47

December 24, 2014

Deep Habits: Three Tips for Taming Undecidable Tasks

Deciding the Undecidable

In a recent blog post I introduced the notion of undecidable tasks — a particularly important type of work that’s not well covered by standard productivity advice.

These tasks are crucial to my job as an academic — as they are to many creative fields — so I devote a lot of attention to understanding how best to tackle them.

Today I want to share three tips along these lines that have worked well for me…

Work on Undecidable Tasks Both During and Outside Work Hours. This type of task often requires a moment of inspiration where the pieces of a new approach suddenly click together. It’s useful, therefore, to not only dedicate regular workday deep work sessions toward their completion, but to also return to them, even if briefly, in unconventional settings more conducive to serendipity, such as while driving or walking the dog. I’ve found both types of thinking are necessary. A lot of intellectual progress can be made in structured sessions at the office while sometimes a hike in the woods is then needed to make use of this progress.

Pursue (Exactly) Two Undecidable Tasks at a Time. Through hundreds of hours of experimentation I’ve found that having two undecidable tasks primed (see below) at a time is optimal. Two is better than one as it allows you to switch your focus if you get stuck (or fed up) with one task. But two is still small enough that your mind can keep the various pieces properly sorted and available for serendipitous reconfiguration.

Undecidable Tasks Require a Decidable Priming. It’s not sufficient to have only a vague understanding of an undecidable task before you dive into solving it. You must first “prime” the problem by working out precisely: (a) what a solution would look like; (b) why standard or simple approaches fail; and (c) a sense of what type of approaches are promising and are worth exploring. This type of priming is a decidable task — something you can schedule and consistently complete in a fixed amount of time — and is something you must do before diving deeper on interesting problems. A non-primed undecidable task is merely a whiff of inspiration — not yet worthy of your limited time and attention.

The above tips have helped my work with the undecidable (i.e., my proof rate is higher when I structure my thinking in this manner). But simple heuristics are just scratching the surface of the fascinating — and under-discussed — intersection between undecidability and productivity.

Better understanding this type of work is something I plan to pursue in the New Year.

December 14, 2014

My New Project, Part 2

December 6, 2014

Deep Habits: Never Plan to “Get Some Work Done”

A Useful Metaphor

In the first chapter of The Happiness Hypothesis, Jonathan Haidt introduces the metaphor of the rider and the elephant. When trying to conceptualize his own weakness in the face of his best intentions, he explains:

I [am] a rider on the back of an elephant. I’m holding the reins in my hands, and by pulling one way or the other I can tell the elephant to turn, to stop, or to go. I can direct things, but only when the elephant doesn’t have desires of his own. When the elephant really wants to do something, I’m no match for him.

Ever since I first read these words, they stuck with me as useful for understanding the working world in particular. The whole edifice that we now call “productivity advice” distills, I realized, to instructions for cajoling the elephant. If you’re not firm, it’ll do what it wants to do.

It’s against this backdrop that I present the following truism about this metaphorical quadruped: if you’re not exceptionally clear about where you want it to go, it will wander.

I noticed this earlier in the week. Some uncertainty in my post-semester schedule left me with an unplanned afternoon at my office. As so many knowledge workers do, I resolved simply “to get some work done.”

Three hours later, I was aghast.

I had spent this period in a state of fierce busyness: many e-mails were answered (yet the issues they concerned never quite got fully resolved), logistics were painstakingly worked out, and I must have made a half-dozen trips to the printer for some unknown reason.

But when I considered the most vital things on my radar — the projects on which almost everything important in my near future career rests — nothing of consequence was accomplished.

People sometimes chide me when I admit my habit of carefully planning every hour of my day (and every day of my week). They think I’m hopelessly rigid and unable to flow with the dynamics of a creative workday.

But it took only one afternoon free from structure to reaffirm what I know to be true. The elephant of your working mind has no interest in bringing you to where you need to go. It will always default to the watering hole of shallow busyness if not reined with confidence.

November 29, 2014

On Undecidable Tasks (Or, How Alan Turing Can Help You Earn a Promotion)

The Decision Problem

In 1928, the mathematician David Hilbert posed a challenge he called the Entscheidungsproblem (which translates to “decision problem”).

Roughly speaking, the problem asks whether their exists an effective procedure (what we would today call an “algorithm”) that can take as input a set of axioms and a mathematical statement, and then decide whether or not the statement can be proved using those axioms and standard logic rules.

Hilbert thought such a procedure probably existed.

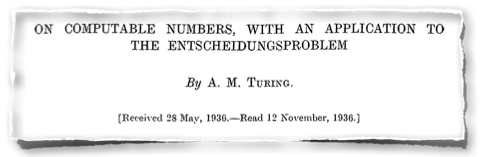

Eight years later, in 1936, a twenty-four year old doctoral student named Alan Turing proved Hilbert wrong with a monumental (and surprisingly readable) paper titled, On Computatble Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem.

In this paper, Turing proved that there exists problems that cannot be solved systematically (i.e., with an algorithm). He then argued that if you could solve Hilbert’s decision problem, you could use this powerful proof machine to solve one of these unsolvable problems: a contradiction!

Though Turing was working before computers, his framework and results formed the foundation of theoretical computer science (my field), as they can be used to explore what can and cannot be solved by computers.

Over time, theoreticians enumerated many problems that cannot be solved using a fixed series of steps. These came to be known as undecidable problems, while those that can be solved mechanistically were called decidable.

The history of theoretical computer science is interesting in its own right, especially given Hollywood’s recent interest in Turing.

But in this post, I want to argue a less expected connection: Turing’s conception of decidable and undecidable problems turns out to provide a useful metaphor for understanding how to increase your value in the knowledge work economy…

Two Types of Tasks

Let’s begin by briefly turning our attention from Turing to something more mundane: tasks in a knowledge work setting.

The standard definition of a task for a knowledge worker is a clear objective that can be divided into a series of concrete next actions. The productivity guru David Allen, who introduced the “next action” terminology, emphasized in Getting Things Done that if you properly break down your tasks into concrete next actions, your day can function like a factory worker “cranking widgets” as you seamlessly shift from one action to the next.

There are parallels between this definition of a task and Turing’s notion of a decidable problem. In both cases, a clear procedure can be systematically applied to the challenge until it’s solved.

But these decidable tasks are not the only type common in knowledge work.

Another type of task are those that have a clear objective but cannot be divided into a clear series of concrete next actions.

For example:

A theoretician trying to solve a proof.

An creative director trying to come up with a new ad campaign.

A novelist trying to write an award-winning book.

A CEO trying to turn around falling revenues.

An entrepreneur trying to come up with a new business idea.

All these examples defy systematic deconstruction into a series of concrete next actions. There’s no clear procedure for consistently accomplishing these goals. They don’t reduce, in other words, to widget cranking.

There are parallels between these types of tasks and Turing’s notion of undecidability. As with Turing’s undecidable problems, any given instance an undecidable task might be solvable, there’s just no systematic approach that’s guaranteed to always work.

On The Value of Undecidability

I argue that the ability to consistently complete undecidable tasks is increasingly valuable in our information economy.

Because these solutions cannot be systematized, this skill cannot be automated or easily outsourced.

Similarly, if you can complete undecidable tasks, you cannot be replaced by a 22-year old willing to work twice your hours at half your pay — as it’s not simply raw effort that matters.

(By contrast, if your day is composed entirely of decidable tasks you’re vulnerable to any of these above dangers.)

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that undecidable tasks are often really hard to complete. Because there’s no easy way to divide them into concrete actions you have to instead throw brain power, experience, creative intuition, and persistence at them, and then hope a solution emerges from some indescribable cognitive alchemy.

You may have guessed where I’m heading with this analysis.

What type of effort supports such difficult cognitive challenges? Deep work.

In other words, understanding the decidable/undecidable task split provides yet another argument for the value of deep work — as it’s only in the cultivation and consistent application of serious concentration that you can expect to succeed where Turing’s machines fail.

November 21, 2014

Deep Habits: Spend Three Months On Important Projects

A Productive King

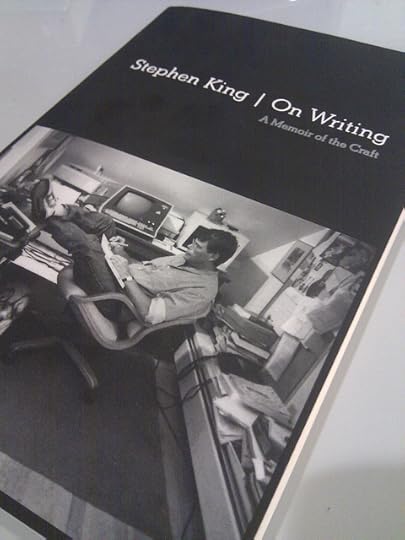

In 2013, during a period of only three months, Stephen King published two full-length novels: Joyland and Doctor Sleep. This is unusually productive, even for a writer whose published fifty-five novels in his career (and sold over 350 million copies along the way).

Perhaps to celebrate this pinnacle of systematic wordsmithing, the Barnes & Noble book blog published a list of twenty tips extracted from King’s 2000 professional memoir, On Writing.

Nestled half way through this list was a piece of advice that caught my attention:

“The first draft of a book—even a long one—should take no more than three months, the length of a season.”

This tip resonates with my experience well beyond just book writing. Things worth doing take time, but if they take too much time your intensity might begin to wane to unproductive levels.

A period of three months seems just about right to hit that sweet spot where you’re accumulating enough deep work to produce something remarkable, but not so much time that your attention begins to diffuse.

(You might be wondering, of course, whether this advice conflicts with my veneration of the multi-year, Steve Martin-style diligent pursuit of becoming too good to be ignored. The expository difference here is that King is talking about a specific project, such as finishing a draft of a book manuscript, whereas my above-mentioned veneration refers to the honing of a craft over many different projects, like Martin’s quest to revolutionize comedy.)

To conclude, there’s nothing magic about three months — some important projects take more time and others take less. But the sentiment driving this advice is crucial.

Focus on things that take enough time to matter, but don’t let their importance dilute your obsessive drive to get something done.

November 18, 2014

It’s Okay to Be Bad at E-mail

The Internet Heretic

I previously admitted that I don’t web surf and that I’ve never had a social media account. This next admission might be the final straw that leads to the permanent revocation of my internet privileges: I’m bad at answering e-mails.

I sometimes go a whole day without looking at my inbox (and sometimes even longer). I ignore messages. People I know well tend to call me when they really need to know something.

I’m not bad at e-mails on purpose. If anything, I’m apologetic and ashamed about it and try to be more responsive when I can. But I only have so many hours to work each day, and I tend to block as much as I can get away with for deep efforts.

This philosophy is a boon to my role as a theoretician trying to solve interesting problems, but a bane to my role as a member of a bureaucracy.

Accepting E-mail Mediocrity

If I step back for a moment, however, it becomes clear that this trade-off makes sense. As a professor at a research institution it’s okay to be bad at e-mail. Indeed, it’s much better that I be bad at e-mail and good at research than the inverse.

And I think this observation generalizes.

At some point in the 1990’s, we (knowledge workers) all seemed to internalize this ethic that any e-mail arriving in our inbox was crucial and important and demanding immediate attention. We were transformed into human network routers fiercely fighting to improve our throughput.

We began to strive for an empty inbox and the most efficient possible strategies for quickly processing this deluge. The twenty-minute response time became an aspirational standard.

But I want to propose an alternative: Not everyone needs to be easily reached by e-mail.

Some people, such as those who deal with clients all day or manage large teams that crave frequent guidance, should be pros at this skill. But other people, like computer programmers, writers, advertising gurus and professors, should be free to suck at e-mail just as much as they might suck at other skills that aren’t that relevant to their core value proposition.

I know this is a basic thing to say, but I suspect it’s worth reiterating.

If you disagree, you could e-mail me about it, but bear with me, it might take me a while to respond.

November 12, 2014

Deep Habits: Obsess When Needed

An Obsessive Digression

For the past two weeks, I’ve been trying to prove a bothersome theorem. It’s not particularly flashy, but I need it for a paper. More importantly, it felt like it should be easy and I took it personally that it’s not.

Predictably, I began to obsess about this proof — by which I mean I took to returning to the proof again and again during breaks in my working day. It became a staple during my commutes to and from work, and began to hijack blocks of time from my otherwise carefully constructed schedules.

Earlier this week, the weather was nice, so while waiting out the traffic at home in the morning I sat outside in my backyard with my grid notebook (something about grid rule aids mathematical thinking) and, as I had been doing, noodled on the theorem.

Except this time: something shook loose.

I scribbled notes for an hour, drove to campus, and set about trying to formalize my new idea.

It didn’t work.

But now I had the scent. Long story short, six hours later I had a proof that seems to work for a more or less reasonable version of the problem (time will tell).

I started that day with a pretty elaborate time block schedule. It was ignored; as was my e-mail inbox; as were several pretty important administrative obligations. But the important thing is that I think I finally tamed that damnable theorem.

Obsession as Productivity Tool

In my work as a theoretician, (bounded) obsession of this type plays an important role in productivity.

A main theorem in this 2014 paper, for example, was finally proved on the metro, whereas the main theorem in this 2013 paper was cracked on a speaking trip to Canada (I started working on it when I arrived at the airport in D.C. and had the key points nailed down by the time my limo arrived at the hotel in Waterloo) . In an interesting coincidence, the breakthroughs in this 2014 paper and this 2011 paper both happened while stuck at home during (different) snow storms.

In all cases, if I hadn’t allowed the relevant problem to evolve into an obsession, I might not have solved it. They required lots of hours of deep thinking under lots of conditions: both products of obsession.

With this in mind, my contention in this post is that this trick of the theoretician is relevant in many more fields.

Important things are hard to do. Obsession supports hard accomplishment.

The challenge, of course, is keeping the obsessions under control (a somewhat oxymoronic task), and learning when to unobsess when progress stalls too much (at best, 1 in 3 of my obsessions yield theorems).

In the final accounting, however, obsession remains a tool that’s not talked about much but should be, as it often plays a key role in elite level knowledge work.

November 10, 2014

Warren Buffett On Goals: If It’s Not The Most Important Thing, Avoid It At All Costs

A Buffett of Advice

My friend Eric recently sent me an article describing advice Warren Buffett once gave an employee.

In the article, Buffett wanted to help his employee get ahead in his working life, so he suggested that the employee list the twenty-five most important things he wanted to accomplish in the next few years. He then had the employee circle the top five and told him to prioritize this smaller list.

All seemed well until the wise Billionaire asked one more question: “What are you going to do with the other twenty things?”

The employee answered: “Well the top five are my primary focus but the other twenty come in at a close second. They are still important so I’ll work on those intermittently as I see fit as I’m getting through my top five. They are not as urgent but I still plan to give them dedicated effort.”

Buffett surprised him with his response: “No. You’ve got it wrong…Everything you didn’t circle just became your ‘avoid at all cost list.'”

An Important Reminder

I read this story on Scott Dinsmore’s site, where Scott explains he heard it from a friend who heard it from the employee in the story: so some details have likely been mutated during this multi-hop dissemination.

But the story nevertheless resonates because it promotes a truth that I think is vital to remember in our current networked age: spending time on lower priority goals, even though they’re helpful and generate value, can leave you worse off than if you had avoided them all together.

The logic supporting this observation is simple.

Your highest priority goals return significantly more value per unit time invested than your lower priority goals.

In addition, your time and attention are limited.

It follows that effort invested on your lower priority goals steals effort from your higher priority goals.

If you spend time on the lower priority goals, therefore, your total quantity of value produced is reduced.

The reason I describe this lesson as particularly vital to our current age is that the behaviors that consume more of our time and attention — e.g., social media, web surfing, chronic networking — often fall onto the low priority end of Buffett’s List of Twenty-Five.

These behaviors are sold to us with the promise that they offer some benefit (e.g., “you never know, the contact you make on Facebook might end up bringing you new business”) – but they do so at the cost of stealing time from the harder efforts that are guaranteed to return a lot of benefit (e.g., make your product too good to be ignored).

It’s with this in mind that it’s useful to remember Buffett’s caution: Don’t just prioritize what’s most important, but support this prioritization by avoiding everything that’s not.

#####

For another take on this idea see Tip #2 in my 2008 article on the Steve Martin Method — the article, interestingly enough, in which I first mentioned his advice to “be so good they can’t ignore you.”

November 6, 2014

Deep Habits: Forget Your Project Ideas (Until You Can’t Forget Them)

An Idea About Ideas

A graduate student recently sent me a note asking how I keep track of potential projects in my academic work. This got me thinking, and after some consideration I decided I had two answers.

The first answer is literal…

Since September, 2004, I’ve always kept an idea notebook with me to capture spontaneous thoughts relevant to many different areas in my life, including potential professional projects. (The picture above is a sampling of my large collection of full idea books.) I try to review my current notebook every couple of months.

The second answer is more honest…

Keeping track of project ideas, in my experience, is usually a waste of time. I used to fear that if I didn’t capture and review my sparks of brilliance I’d forget them and an opportunity for impact would be lost.

The reality, however, is that most people (myself included) have way more ideas for things to work on than they have time to work. Forgetting ideas is not your problem. Having too many ideas competing for your attention to execute any one well is a more pressing concern.

(This notion that ideas are cheap and execution valuable is not, of course, new: it’s been circulating through Silicon Valley start-up circles for a while; c.f., here and here.)

But my dismissal of tracking project ideas is about more than the relative unimportance of ideas compared to execution. I argue that the refusal to implement a system for curating these ideas provides an active strategy for figuring out what to work on.

In more detail, in recent years I’ve found that a useful criteria for selecting an idea to deliberately attack (both in academia and my book writing) is that it won’t leave me alone; it keeps coming back to my attention even though I’m not trying to remind myself about it.

This act of subconscious selection is not arbitrary. Indeed, there’s a growing body of evidence that for certain types of decisions your unconscious mind is better at sifting through conflicting variables and reaching a sound decision than more systematic conscious thought.

This approach works well for me. I expose myself to lots of different ideas and I dabble in many of them (a conversation here, a few equations scratched out there, a commute dedicated to noodling an interesting theorem), all the while not worrying too much about capturing every potential concept in some convoluted Evernoted nonsense.

I don’t mind if I forget moments of inspiration. The important piece is that I won’t deeply commit myself to a project until the damn thing won’t leave me alone.

November 3, 2014

Doing What it Takes Versus Taking What You Already Know How to Do

The Unexpected Nobel

Eric Betzig is a research leader at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Virginia. Last month he received a surprising and life changing call: he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on high resolution microscopy (see the video above).

Everyone who wins the Nobel is impressive, but what makes Betzig particularly worthy of attention is his unlikely path to the prize. One thing that any non-partial observer will confirm is that if you had met Betzig in 1994, the idea that he would one day win the most prestigious award in science would seem strictly absurd.

The Retreat

As scientists go, Betzig had a strong start. As he recounts in a Washington Post profile, as a child Betzig was captivated by the space race. “I can still you the names of the astronauts on every flight from Mercury to Apollo,” he said.

This motivated him to study physics at Cal Tech. After he graduated in 1983, he went on to earn his PhD in applied physics at Cornell.

At this point, the excitement surrounding the space program had waned, so Betzig ended up studying high resolution microscopy for his dissertation — a field that was becoming hot as new technology enabled breakthroughs in the resolution of microscopes.

In 1988, Betzig moved to Bell Labs to continue his work on microscopes. At Bell Labs, Betzig helped improve a pioneering procedure for detecting the light absorption of single molecules to work at room temperature (the original experiments had required temperatures near absolute zero).

At some point, however, Betzig began to feel “restless.” Technology wasn’t ready to capitalize on the techniques he was helping to develop.

“Science goes through fads and there are big ups and crashes,” Betzig recalled in the Post profile. “[The] microscopy we were using was going through one of those fad phases, which disturbed me. It was being grossly oversold.”

In 1994 he quit Bell Labs to join his father’s Michigan-based tool and die company, where he would remain for the next seven years.

The Return

In the early 2000’s, Betzig was someone who had been involved in promising research a decade earlier, but not anything that was Nobel-worthy. He had subsequently spent the last seven years helping his dad’s company optimize procedures for large-scale production of machine parts.

Nothing about this his resume predicted what would happen next.

Betzig decided that he “missed the basic curiosity of the lab.” He wanted to return to academia, but he also knew that his seven years working in industry and not publishing made that almost impossible.

The keyword being “almost.”

Betzig concluded that his only way back into the world of academic science was to hit a home run. So he began searching for a good pitch to swing at.

This search, at one point, led him and Harald Hess, an old Bell Labs collaborator, to Mike Davidson’s lab at Florida State where he learned about a new technique for fluorescing proteins. Though the details of the explanation are complicated, this breakthrough, Betzig noticed, made it theoretically possible to advance the research he had started in the 1980’s.

Working in Harald Hess’s living room, the pair began making phone calls and begging for some fluorescing proteins. They then started cobbling together different prototypes of microscopes that would use these proteins to achieve unprecedented resolution.

Their final result was attention-grabbing in the field: a microscope able to visualize the biological processes of living cells, in real time, without damaging the organisms. A major breakthrough.

The year was 2006. Within a month, Howard Hughes Medical center offered Betzig a research position to continue the work. In 2014, this work won him the Nobel.

The Lesson

Soon after Betzig won the prize, several readers sent me versions of his story. When I read it, I was struck by the following observation: When Eric Betzig wanted to return to academia, he asked, “what would this take?” The answer was daunting — a breakthrough too good to be ignored — but nonetheless he hustled to make it happen.

This strategy sounds obvious, but it differs from how most of us approach professional advancement. When faced with an ambitious goal, most people defer instead to the question”what do I know I how to do and how can I make it look better?”

We take what we can do, in other words, instead of facing the reality of what it would take to get where we want to go.

I don’t exempt myself from this vice, and for this reason it fascinates me. Why is it so rare to honestly confront what would guarantee success with a goal ? Why do we instead default to tweaks and polishes on what we already know how to do? Why, for example, don’t more academics obsessively pursue the type of home run swings that Betzig identified as being necessary when he decided to return to the world of science?

There are some obvious answers to these questions, chief among them being discomfort with the answers that such honesty reveals, and there are some mysteries as well.

But what’s clear is that these questions remain something that I think anyone seeking an elite level of accomplishment must, at some point, confront. I also suspect that one of the main filters between those who end up changing the world and those who don’t is how they answer this unavoidable prompt.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers