Cal Newport's Blog, page 44

August 13, 2015

Deep Habits: Process Trumps Results for Daily Planning

The Planning Pitfall

Daily plans are tricky.

As I’ve long maintained, if you don’t give your time a job, it will dissipate in a fog of distracted tinkering. Simply having a to-do list isn’t enough: you need to provide the executive center of your brain a more detailed target to lock onto.

There is, however, a pitfall with this productivity strategy that I stumble into time and again: it’s easy to start associating “success” for your day with accomplishing your plan exactly as first envisioned, and to label any other outcome as a “failure” — a belief that triggers near constant frustration for most jobs.

The reality of daily scale productivity is that plans are not meant to be preserved. They’re instead meant as a device for ensuring that you tackle your day with deliberation.

Of course your carefully partitioned time blocks will be disrupted (how can you possibly predict the many ways in which your schedule might fall apart in the Age of E-mail?).

After such disruptions, you simply need to form a new plan for the time that remains — preserving your deliberative mindset. But it’s easy to cling to the idea that your original plan was somehow the best possible way for your day to unfold.

When I catch myself falling into this trap and despairing how far I’ve veered from some pristine but ultimately impossible ideal for my day, I’ve found it helpful to remember a simple heuristic: judge your day on how well your executed your productivity process, not the details of what you actually produced.

August 4, 2015

Einstein Was Boring Before He Was Brilliant

The Einstein Myth

The story has become lore.

Albert Einstein was a rebellious student who chafed against traditional schooling and earned bad grades. After his university education, his brilliance was overlooked by a conformist academy who refused to give him a professorship. Broke and unemployed, Einstein settled for a lowly job as a patent clerk.

But this turned out to be a blessing in disguise. Free from the bonds of conventional wisdom, he could think bold, original thoughts that changed the world of physics.

The reality, of course, is more complicated.

Einstein was a rebellious student, but he always received exceptional marks in math and physics in school and on entrance exams.

Einstein did struggle after college, but he wasn’t turned down for professorships. What he failed to obtain after graduation was a university assistantship — which is, roughly speaking, a way to fund a graduate student while he or she works on a doctoral dissertation (like what we now call a research assistantship in American graduate education).

This was not a case of his brilliance being ignored, because Einstein was to early in his education to have done anything brilliant yet (the paper on capillary action he published the year after his graduation was mediocre). The main reason for his assistantship rejection was a bad recommendation letter from a professor who didn’t like him.

The key detail often missed in this story is that while Einstein was a patent clerk, he was continuing to work toward his doctoral degree. He had an adviser, he was reading and writing, he met regularly with a study group (pictured above).

The same year Einstein published his ground breaking work on special relativity (1905) he also submitted his dissertation and earned his PhD. Soon after he received professorship offers, and his academic career took off.

In other words, Einstein had to work a job to support his family while earning his PhD (an exhausting turn of bad luck), but his career from university to graduate degree to professorship still followed a pretty standard trajectory and timeline.

The Conformist Path to Innovation

The reason I’m telling this story is because it underscores a common habit: we like to cast innovators as outsiders who leverage their freedom from tradition-bound institutions to change the world.

In reality, innovation almost always requires long periods of quite traditional training.

Einstein was brilliant and original, but until he finished a full graduate education, he didn’t know enough physics to advance it.

The same story can be told of many other innovators.

Take Steve Jobs: the Apple II was lucky timing; Jobs didn’t become a great CEO until after spending decades struggling to master the world of business. Once his skills were honed, however, he returned to Apple and his brilliance had an outlet.

This is the hard thing about innovation. If we want to encourage people to change the world, we have to first encourage them to buckle down and work inside the box.

The tricky part is embracing this necessary conformity while somehow keeping that spark to think different alive long enough for you to get good enough to do good.

July 27, 2015

Tim Ferriss in a Toga: The Ancient Greeks on Labor and the Good Life

The Wondrous Water Wheel

Writing in the first century B.C., Anitpater of Thessalonica made one of the first known references to the water wheel:

“Cease from grinding, ye women who toil at the mill; sleep late even if the crowing cocks announce the dawn. For Demeter has ordered the Nymphs to perform the work of your hands, and they, leaping down on the top of the wheel, turn its axle….we taste again the joys of the primitive life, learning to feast on the products of Demeter without labor.”

I recently encountered this quote in Lewis Mumford’s seminal 1934 book, Technics & Civilization. As Mumford points out (drawing some on Marx), the striking thing about Anitpater’s reference to the water wheel is how its beneficiaries responded: This tool reduced their labor, so they reinvested that time in non-labor activities (“sleep late even if the crowing cocks announce dawn”).

This is a point that Mumford makes elsewhere in the book: in many times and cultures (and especially in ancient Greece), there was a notion of the right amount of work to support your profession. Once you reached that level, you were expected to turn your remaining attention to other matters like food, play, politics, and the intellectual life.

If new tools helped you reach that level sooner, then you had that much more time to yourself.

Labor and Culture

This idea caught my attention for two reasons.

First, I liked the connections between this ancient norm and the contemporary lifestyle design movement. Antipater’s Greeks are like Tim Ferriss in a toga.

Second, it contrasts strongly with modern Western culture where “labor saving” innovations, especially in the digital domain, tend to create new labor, and ratchet busyness to higher levels.

Imagine, for example, if we had confronted e-mail (my obsession of the moment) like Anitpater’s Greeks; perhaps designing e-mail servers to deliver messages only three times a day, as was the case with memos and letters, but saving people the trouble of stamps or visits to the mail room. In other words, imagine if the technology had strictly reduced labor instead of increasing it vastly.

The above example is problematic (e-mail certainly eliminated other massive inefficiencies), but the broader point is interesting. We approach technology though a cultural lens. The more we recognize this, the more options we encounter for shaping our working lives toward what matters to us.

July 7, 2015

Deep Habits: Write Your Own E-mail Protocols

The Curse of Process Inefficiency

A couple weeks ago, I posted some ideas about why we have such a love/hate relationship with e-mail. In this post, I want to return to the conversation with a thought on how we might improve matters.

I argue that a major problem with our current e-mail habits is interaction inefficiency.

In more detail, most e-mail threads are initiated with a specific goal in mind. For example, here are the goals associated with the last three e-mails I sent today before my work shutdown:

Getting advice from my agent on a publishing question.

Moving a meeting to deal with a scheduling conflict.

Agreeing on the next steps of a project I’m working on with Scott Young.

If you study the transcripts of most e-mail threads, the back and forth messaging will reveal a highly inefficient process for accomplishing the thread’s goal.

There’s a simple explanation for this reality. When most people (myself included) check e-mail, we’re often optimizing the wrong metric: the speed with which you clear messages.

Boosting this metric feels good in the moment — as if you’re really accomplishing something — but the side effect is ambiguous and minimally useful message that cause the threads to persist much longer than necessary, devouring your time and attention along the way.

I’m as guilty of this as anyone. For example, look at this terrible reply to a meeting request that I actually sent not long ago:

I’m definitely game to catch up this week.

Ugh. As I sent the above I knew that in the interest of replying as quickly as possible, I probably tripled the number of messages required before this meeting came to fruition.

E-mail Protocols

What’s the solution?

Here’s a tactic that I’ve sporadically toyed with and that seems to work well: when starting or first replying to an e-mail thread, include in your message a “protocol” which identifies the goal of the thread and outlines an efficient process for accomplishing the goal (where “efficient” usually means a process that minimizes the total number of e-mails sent).

Consider, for example, the following improved version of my above response:

I’m definitely game to catch up this week. See below…

—–

Here are three time and date combinations that work for me to talk this week. If any of these three work for you, choose one: I’ll consider your reply a confirmation of the call. You can reach me then at .

If none of these work, reply with a few combinations that do work, and I’ll choose one.

Option #1:

Option #2:

Option #3:

Notice the format of this message. It opens with the normal informal tone that people expect from e-mail, and then segregates the more systematic protocol portion under a dividing line. In this case, the sample protocol is designed to reduce the thread to two e-mail messages if at all possible.

Pros and Cons

The hard part about this strategy is that it takes a little more time to craft each of your messages. It returns, however, two important benefits…

The first benefit is obvious: a well-designed protocol will reduce the number of e-mails you send and receive, and therefore reduce the overall time you spend tending your inbox (even if the messages you do send take slightly longer to write).

The second benefit is less obvious in the abstract but clear in practice: you feel less stress. When you fire off a quick and ambiguous e-mail, your mind knows the related project is still open, and therefore it will reserve some mental space to keep worrying about it.

If you instead identify the relevant goal and lay out a clear process for accomplishing it, your mind believes things are handled, and it’s more willing to let it go.

I know it sounds weird, but it’s true: including protocols in your e-mail, though somewhat clunky and artificial, really does reduce the grip your inbox has on your mood and attention.

I don’t use this strategy nearly as much as I should, but whenever I do, it works wonders for me. If your inbox is frustrating you, it’s worth experimenting with. I’ll be interested to hear about your experience.

June 25, 2015

Barack Obama on Craftsmanship

Obama’s Craft

Last winter, I posted a quote from Barack Obama where he discusses his commitment to honing his craft. Earlier this week, we received more evidence of this presidential craftsmanship.

With three minutes and twenty seconds left in his interview with Marc Maron, (released Monday), Obama said the following:

The more you do something, and the more you practice it, at a certain point it becomes second nature. What I’ve always been impressed with about when I listen to comics talk about comedy is how much of it is a craft. Right? They’re thinking it through, and they had a sense of when it works and when it doesn’t. The longer you do it the better your instincts are.

A strong endorsement for the simple pleasure of putting in the hours to do something well.

(Image from Humans of New York.)

June 18, 2015

The E-mail Productivity Curve

A Mixed Response

Late last year, Pew Research found that online workers identified e-mail as their most important tool, beating out both phones and the Internet by sizable margins. Almost half of the workers surveyed claimed that the technology made them “feel more productive.”

As Pew summarized: “[e-mail] continues to be the main digital artery that workers believe is important to their job.”

Around the same time this research was released, however, Sir Cary Cooper, a professor of organizational psychology, made waves at the British Psychological Society’s annual conference by identifying British workers’ “macho,” always-connected e-mail culture as a factor in the UK’s falling productivity (it now has the second-lowest productivity in the G7).

Cooper went so far as to advocate companies shutting down their e-mail servers after work hours and perhaps even banning all internal e-mail communication.

This bipolar reaction to e-mail — either it’s fundamental to success or terrible — extends beyond research circles and often characterizes popular conversations about the technology.

So what explains this oddly mixed reaction?

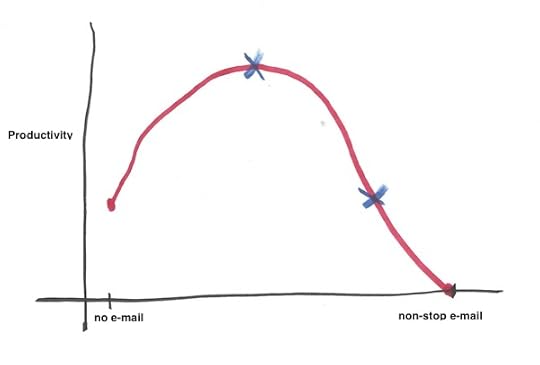

I propose that the productivity curve at the top of this post provides some answers…

The E-mail Productivity Curve

The above curve shows the rise and fall of productivity (y-axis) as e-mail use (x-axis) increases from a minimum of no e-mail to a theoretical maximum of non-stop e-mail use.

Notice, at the left most extreme (i.e., no e-mail use) productivity remains healthily above zero. This captures the obvious reality that even if e-mail (and similar digital communication tools) were banned, companies could still get stuff done, as they did in the many decades before such technologies were introduced.

As we begin to move to the right (increasing e-mail use) productivity increases. This point should also be obvious. It’s hard to argue against the proposition that e-mail is an immensely useful technology: universal addressing, instant information transfer, asynchronous storage and retrieval — these are all hard communication problems that e-mail solves elegantly.

As we continue to move to the right, however, things get interesting.

Eventually we will arrive at a theoretical maximum point on the x-axis where all workers ever do is check and send e-mails. At this point, no time is left for any actual work, so productivity would be zero.

If we step back, we see our three obvious observations from above tell us the following about any curve that describes a measure of productivity versus increasing e-mail use: the curve will start above zero; it will rise for a while; and it will eventually decrease all the way down to zero.

Any curve matching these criteria will, like the sample curve above, features two crucial points: one where the productivity produced by e-mail use hits a maximum point (marked by the first blue X above), and a break-even point after which e-mail use makes users less productive than if they didn’t have e-mail at all (the second blue X).

I propose that the mixed reaction to e-mail summarized at the beginning of this post can be better understood with respect to the different regions of this curve.

In more detail…

Those who aggressively defend the e-mail (like the workers surveyed by Pew), are responding to the reality that much of this productivity curve is above the no e-mail level. That is, they’re reacting to the true observation that e-mail can make you more productive than no e-mail.

Those who decry e-mail (like Cary Cooper), are responding to the reality that an increasing number of organizations are to the right of the first blue X (and perhaps even to the right of the second X), and therefore their e-mail habits are making them less productive than they could be if they were more discerning about their use of this technology.

It’s possible, in other words, for your e-mail use to be both making you more productive (as compared to no e-mail) and less productive (as compared to its optimal use).

Holding both these thoughts in one’s head at the same time can be confusing — thus explaining, to some degree, the muddled polarization of e-mail rhetoric.

From Explanation to Opportunity

Once we understand this style of productivity curve, however, we can do more than simply demystify our confusion, we can also recognize a major management opportunity.

With few exceptions, e-mail use arose organically within organizations, with little thought applied to how digital communication might best serve the relevant objectives.

The result is that e-mail habits tend to fall somewhat haphazardly on the e-mail productivity curve, with a bias toward to the right-hand side (as increased connectivity tends to be more convenient for people in the moment, especially when unchecked by other metrics).

It’s important to note that there’s nothing fundamental about these current e-mail habits: an observation which leads to the conclusion that forward thinking organizations could consider exploring different regions of this curve in search of the optimal point.

By thinking in terms of a search for optimality, such organizations could escape the e-mail is either bad or good dichotomy that often cripples such initiatives before they get too far, and instead cast the efforts in terms of process optimization.

To reduce e-mail use, in other words, is not necessarily a repudiation of the technology, but can be instead an embrace of its full potential.

June 15, 2015

Pursue Metrics that Matter

Three Measures of Success

I’ve been thinking recently about the metrics we use to measure success when pursuing self-motivated ambitions. These metrics tend to fall into three major categories, which I’ll list from easiest to hardest to achieve:

Participation Metrics: The goal here is to simply invest regular time toward the ambition. For example, if you want to become a writer, this might involve creating a daily writing ritual.

Unconventional Custom Metrics: The goal here is now clarified to specify concrete outcomes, but these outcomes tend to be custom-built and not widely recognized as marks of success in the field. Returning to our writer example, a custom path to success might steer toward self-publishing, with much of your focus now directed on mastering the technical mechanics of Scribner, KDP, freelance cover designs, and well-paced e-mail marketing campaigns.

Conventional Competitive Metrics: The goal here is to achieve outcomes that are widely recognized as impressive. In our writer example, this might be a big book deal with a major publisher.

The Power of Competition

When it comes to the three categories from above, I think the first category is reasonable for dabbling with a topic, but it won’t take you much farther than that, so you shouldn’t be satisfied with this measure of success for too long.

The second category is more worrisome.

These unconventional metrics are insidious because they provide enough illusion of accomplishment to keep hijacking your limited energy, but ultimately they rarely provide much return.

The reason they deliver so little is that they’re usually designed to avoid competition checkpoints — steps in the process where many aspirants enter, but only a much smaller number win the ability to continue. This might sound nice, but such checkpoints are crucial for advancement in many ambitions. It’s these competitive clashes that force you to hear someone say, “this is not good,” and therefore find the motivation to return to the woodshed for more of the inevitable hard practice, driven to produce a different outcome.

This final point is why I like the third type of metric. Pursuing highly competitive and unambiguous definitions of success for a given ambition, if you persist, will force you to improve your skills at a rapid and sustained rate. This process can be ego-crushing at times (as I know from many personal experience in writing and academia), and in the moment it’s much less satisfying than implementing some hyper-specific life hacks, but it’s this scramble to win a limited resource that forges professional talent.

So this is my simple observation: When deciding to embrace a self-motivated ambition, choose a definition of success that your aunt in Peoria would understand and find impressive. This is not about succumbing to the status quo, but instead setting yourself up to receive the brutal but useful feedback needed to eventually start producing things too good to be ignored.

(Photo by shutterbugamar)

June 9, 2015

Deep Habits: Spend Six Months to Master Skills

Musical Wisdom

Not long ago, a reader pointed me to an article written by Josh Linkner, a jazz guitarist turned tech entrepreneur. In this article, Linkner recalls a piece of wisdom common among professional musicians: a new (musical) technique takes six months to master. As he expands:

I may have understood the scale, riff, or chord…but it took a good six months to internalize it and make it my own. If I wanted to perform something fresh, new, and bold, I needed to begin the learning process six months prior.

Linkner then makes the natural connection between the world of music and business. The same six month rule, he notes, applies to many skills that might give you a competitive edge in your professional life:

If you want to become reasonably knowledgeable in Asian currency fluctuations, salmon fisheries, or assembly line logistics, a solid six months of study will bring you to point where you can hold a thoughtful conversation.

I strongly agree.

I know I sometimes fetishize the long process of developing a craft through deep work, but it’s important to remember that this long process often partitions into many smaller, reasonably self-contained projects — each of which delivers its own benefit to your career.

Linkner, in other words, is identifying a pragmatic way to structure the task of building rare and valuable skills. Instead of asking what you should be doing for the next decade to become too good to be ignored, ask what you could do in the next six months to become demonstrably better at something that matters.

#####

On an unrelated note, I recently read an advance copy of Laura Vanderkam’s excellent new book, I Know How She Does It, which tackles the topic of how successful women manage the tension between professional and family life. Unlike many treatments of this topic, which rely on anecdotes and personal opinion, this book instead draws from an extensive data set of detailed time logs that Laura gathered from a large sample of successful women. The result is surprisingly optimistic and refreshingly unemotional. If this topic interests you: take a closer look.

(Photo from joshlinkner.com)

June 4, 2015

Don’t Trust Anyone Under 500: Dale Davidson’s Unconventional Advice for Graduates

My friend Dale Davidson runs the excellent Ancient Wisdom Project blog, where he chronicles his experience with 30-day experiments, each dedicated toward living a practice from an ancient religion or philosophy, pursued in the service of deep personal growth. I’m always impressed by Dale’s thinking, so I asked if he would provide me something provocative to post for graduation season.

Fortunately for us, he obliged. Below is an open letter Dale wrote to the graduating class of 2015.

Don’t Trust Anyone Under 500

By Dale Davidson

To the class of 2015,

With graduation season upon us, you have likely been hearing a lot of advice about how to live your life. Regardless of what anyone tells you, I ask that you do one thing: consider how old it is.

***

I graduated college in 2009 fully intending to become a Navy SEAL. I was accepted into SEAL training, and several months later, for reasons I’m still not sure about, I quit.

I was thrust back into “civilian life” and felt aimless. What should I do now? I first turned to the Internet in search of wisdom (always a risky endeavor). I read The Four Hour Work Week, a book by lifestyle designer Tim Ferriss who advocates becoming incredibly productive and minimizing doing work you dislike and spending most of your time doing only things you enjoy. I followed travel bloggers who quit their jobs to spend a year traveling around the world and fantasized about doing the same. I discovered the pop psychology advice genre that turns psychological research into advice on becoming happy.

This advice didn’t work. I ended up more confused and lost about what I should be doing with my life.

So last year I decided to try something different. I decided to look to ancient sources of wisdom for advice on how to live a good and meaningful life and created what I call The Ancient Wisdom Project.

The rules of the project are simple:

Choose one ancient religion or philosophy that is 500 years old and that stills exist in some form today

Select one practice from the religion or philosophy that would help cultivate a desirable virtue (compassion, humility, etc.)

Perform the practice for thirty days and write about it

The results of these experiments were powerful, certainly far more powerful than anything I found in modern self-help literature. Here are just a few of the lessons I learned that I hope will encourage you to take a similar approach to evaluating the advice you receive in the coming months.

Pursue virtue, not success

The core belief in our meritocratic culture is that you can achieve great success if you work hard enough. The risk of this thinking is we become too attached to our desire for success, rather than the cultivation of a coherent and virtuous moral character.

Stoicism, an ancient Greek philosophy, is premised on the idea that there are certain things within your control, and far more things that are not.

My practice and study of Stoicism, which included daily ice baths and negative visualization exercises, confirmed that this ancient insight is still relevant to our modern lives.

Some things are in our control and others not. Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion, and, in a word, whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command, and, in one word, whatever are not our own actions.

– Epictetus

You can control how hard you work and how virtuously you behave; you cannot control how fast you receive promotions. You can control how you treat others; you can’t control how well others treat you. They knew the rewards for cultivating strength in heart and mind are far greater than the rewards of pursuing worldly success, which will always remain just outside of your control.

Modern advice tells us to pursue accomplishments.

Ancient wisdom tells us to live virtuously.

Forget yourself

Last year, I wanted to quit my job. It wasn’t that it was particularly hard, rather, it was incredibly boring and seemingly meaningless. Though it was tempting to follow modern career advice and quit to do something more interesting, I resisted, and dived into my Catholic month.

My experiment with Catholicism, which included Jesuit spiritual exercises and daily attendance at Mass, taught me that giving oneself to the service of others is far more gratifying than pursuing self-interest. I came away acknowledging how much energy I was spending on obsessing on my own desires for the perfect job, energy that could be better spent, perhaps, thinking of ways to serve others.

A few weeks later I started volunteering at Miriam’s Kitchen. A few hours per month serving breakfast to the homeless, while certainly a small contribution, has made me feel like at least some of my work is doing some good in the world. More importantly, doing something for others lets your forget your own desires, which is a relief! Thinking about what you want all the time is exhausting.

You, my brothers and sisters, were called to be free. But do not use your freedom to indulge the flesh; rather, serve one another humbly in love.

– Galatians 5:13

It’s also important to not think too highly of yourself. During my Islam month, I practiced Salat, or prayer, five times per day with the goal of cultivating humility. These prayers, inconvenient by design, acted as a sort of check against my arrogant tendencies. I became aware of how much I resented my co-workers as idiots or sheep. Though I can’t say that those feelings are gone, I find that simply acknowledging them allows me to be more open and less frustrated with others.

Bring anger and pride under your feet, turn them into a ladder and climb higher…

Don’t become its victim you need humility to climb to freedom.

– Rumi

A commitment to humility and service requires a systematic emptying of the self, a practice in which ancient religions excel.

Modern advice tells us to enlarge the self.

Ancient wisdom tells us diminish the self for others.

Get a real life

As new graduates, you will have to work hard as you start your careers. But at some point you will realize that work can’t fulfill all your needs. You might think you need more “work-life balance,” but simply reducing the amount of time you spend at work is not sufficient for creating a life.

During my Judaism month, I attended daily Minyan services (a type of prayer service) at a local synagogue. The Minyan was mostly filled with retired people (it was a 7:30 AM service, after all), and it mostly consisted of regulars.

While they all began attending for different reasons, they all found that actively setting aside time each week to communally study and pray added a layer of depth to their lives that is increasingly rare in a rushed society that promotes passive rest rather than spiritual recovery.

These voluntary obligations outside of work are necessary and difficult. I attempted to observe Shabbat (the Sabbath), which begins at sundown on Friday and ends at sundown on Saturday. Shabbat advocates a powerful combination of removing the profane distractions of everyday life and adding active participation in sacred rituals that allow us to connect more deeply with our humanity.

Ban yourself from using your laptop or phone during Shabbat and you will find time to read, take long walks, and contemplate. If you make the necessary preparations to host a Shabbat dinner, you will renew your relationships with your friends and family over food and wine without the distractions of a noisy bar.

The Sabbath is a day for the sake of life. Man is not a beast of burden, and the Sabbath is not for the purpose of enhancing the efficiency of his work. ‘Last in creation, first in intention,’ the Sabbath is ‘the end of the creation of heaven and earth

— Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath

While not as easy as ordering a pizza and turning on Netflix on a Friday night, committing to this ancient system of sacred rest and spiritual renewal is far more rewarding.

Modern advice encourages us to achieve work-life balance.

Ancient wisdom tells us to work hard at building a life.

***

I chose the 500 years criterion somewhat arbitrarily. I figured if a particular philosophy or religion has survived at least five centuries there must be some value to it. It’s not perfect, but after a year of experimenting with this heuristic I find it works remarkably well for evaluating the advice I receive.

So the next time you are looking for advice on the way forward, you might turn to a theologian, prophet, philosopher, or saint before any modern-day blogger (except for me, of course).

Don’t trust anyone under 500.

(Photo by Hartwig HKD)

May 18, 2015

The Eureka Myth: Why Darwin (not Draper) is the Right Model for Creative Thinking

The Inspiring Story: A Brilliant Mind “Thinks Different”

In a pivotal scene in the Stephen Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything, the physicist is staring into the embers of a dying fire when he has an epiphany: black holes emit heat!

The next scene shows Hawking triumphantly announcing his result to a stunned audience — and just like that, his insight vaults him into the ranks of scientific stardom.

This story is inspirational. But as the physicist Leonard Mlodinow points out in a recent New York Times op-ed, it’s not at all how Hawking’s breakthrough actually happened…

The Stubborn Reality: A Highly-Trained Mathematician Works Hard

In reality, Hawking had encountered a theory by two Russian physicists that argued rotating black holes should emit energy until they slowed to a stationary configuration.

Hawking, who at the time was a promising young scientist who had not yet made his mark, was intrigued, but also skeptical.

So he decided to look deeper .

In the (many) months that followed, Hawking trained his preternatural analytical skill to investigate the validity of the Russians’ claims. This task required any number of minor breakthroughs, all orbiting the need to somehow reconcile (in a targeted way) both quantum theory and relativity.

This was really hard work.

The number of physicists at the time with enough specialized training and grit to follow through this investigation probably wouldn’t have filled a moderate size classroom.

But Hawking persisted.

And to his eventual “surprise and annoyance,” his mathematics confirmed an even more shocking conclusion: even stationary black holes can emit heat.

There was no fireside eureka moment, but instead a growing awareness that gained traction as the mathematics were refined and checked again and again.

The Eureka Myth

Mlodinow tells this story as one of many examples of scientific discoveries incorrectly portrayed as the result of sudden insight. (He also places Darwin’s finches and Newton’s apple in this category.)

There are many lessons that can be drawn from Mlodinow’s article, but there’s one in particular I want to highlight here: we need to rethink creativity.

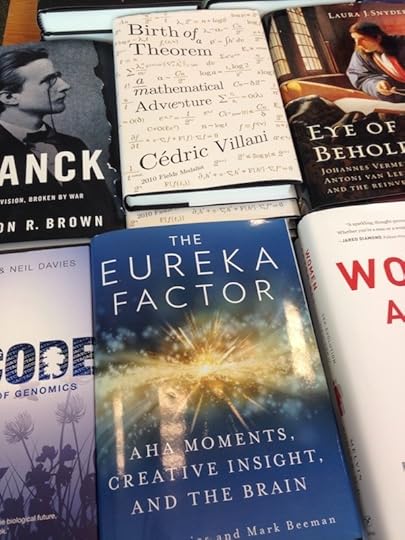

This idea came to me soon after I read Mlodinow’s op-ed. Later that morning I was at Barnes & Noble, still thinking about his points, when I saw the table display pictured above.

The two books placed right next to each other on the display, I realized, capture a fundamental rift in our culture’s thinking on creativity.

The bottom book, titled The Eureka Factor, explains, among other things, how to setup your environment to be more “conducive” to generating “creative insights” of the type portrayed in The Theory of Everything.

The top book, titled Birth of a Theorem (which I bought and read this weekend), is written by the french mathematician Cedric Villani. It tells the tale (without undue exposition or elision) of how he came to solve the theorem that won him the 2010 Fields Medal.

The former promotes a Don Draper style story that we like to hear: if you’re willing to open yourself to your own genius, you’ll have eureka moments that change your life.

The latter paints the Stephan Hawking style reality of what produces real creativity: hard won skills are put to work in a painstaking, obsessive way to uncover, one cognitive brush stroke at a time, something fundamentally new.

In an economy where creativity is becoming both more important and complicated, I suspect we need to abandon the old ways of thinking about this type of thinking, with its conference room brainstorming sessions and markers on butcher paper, and instead discover what scientists knew along: creativity is hard, highly skilled work that is often quite unromantic in its execution, but is ultimately a source of deeper satisfaction than any short-lived eureka moment could ever deliver.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers