Cal Newport's Blog, page 41

April 5, 2016

Is Email Sinking the U.S. Economy?

A Productive Mystery

Reading the Washington Post this weekend, Robert Samuelson’s column caught my attention. It was titled, “Solving the productivity mystery,” and it focused on a trend that both concerns and puzzles economists: productivity has stopped growing.

This statement requires some unpacking.

In economics, productivity, roughly defined, measures the ratio of output to inputs. The more valuable output you can produce for the same input costs, the better your productivity.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics expends a lot of effort to carefully measure this metric over many different industries in our country as it tends to be a strong indicator of practical things that people care about, like wage increases.

Back to the Samuelson column…

From 1995 to 2005, labor productivity increased by an average of 2.5% a year. As Samuelson pointed out, this translates to wage increases of roughly 25% over that period. This is good.

From 2010 to 2015, however, the average increase has only been 0.3% a year. If this persists through 2020, it will translate to a “puny” 3% wage increase over the decade. This is not good.

The puzzle, as mentioned above, is understanding why productivity is slowing.

There are no shortage of hypotheses. Samuelson reviews several in his column, including Robert Gordon’s claim that serious innovation is fading (c.f., Gordon’s big deal new book), and Samuelson’s own theory concerning the inefficiency of duplicating sales efforts online and in physical stores.

An Intriguing Angle

I’m not an economist, so it’s with trepidation that I throw one more potential contributing factor into the mix: email.

Hear me out.

The period between 2010 to 2015 is when smartphone use transitioned from popular to ubiquitous (I bought my first smartphone in 2012), and with this transition new expectations about constant connectivity migrated from the social sphere to the workplace.

Not surprisingly, many in the knowledge sector (and beyond) talk about the last five years as a tipping point where their annoyance with their various inboxes metastasized to deep, soul crushing resentment.

With this rise of constant connectivity — as I’ve documented in detail — a drop in cognitive ability is absolutely unavoidable.

This would be okay if our ability to think clearly and efficiently didn’t matter for the bottom line. But it does!

The main capital expenditure in the powerful knowledge sector of our economy is human brains: by reducing their ability to effectively produce valuable output, wouldn’t we expect a slow down in labor productivity?

(It’s here that many connectivity apologists began to talk about the soft opportunities and advantages of increased information and connection. But labor metrics are harsh. An active presence on social media or rapid email response times often do not measurably lead to more production of unambiguously rare and valuable output.)

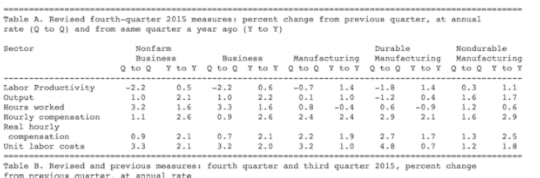

Some modest support for this thesis shows up if you look hard enough (and embrace sufficient selection bias):

The March productivity numbers, for example, show that the “business” category (which includes knowledge work) has a notably smaller increase in productivity than the various manufacturing industries measured.

Tier one knowledge companies like Google are increasingly having to rely on “sprints,” in which a development team drops off the grid, and works night and day to hit a self-imposed deadline. I suspect — though can’t claim with confidence — that these sprints became necessary because without permission to disconnect from the message whirlwind, the average developer is too riddled with distraction to produce good code anywhere near cognitive capacity.

I don’t want to fall into an econometric rabbit hole here, so let’s treat Samuelson’s column mainly as a prompt to return to a pertinent issue: Just because constant connectivity has become the standard approach to work doesn’t mean that it’s good.

The time has come, in other words, to step back from this inbox-driven world we’ve created and ask with clarity and humility: does this make any sense?

April 1, 2016

On Using Inspiring Locations to Inspire Deeper Work

A Rite of Spring

The return of spring marks the return of one of my favorite deep work strategies: the concentration circuit.

This strategy helps you make progress on a cognitively demanding task by having you work in a rotating series of locations that are: (1) not your normal office; (2) novel and/or aesthetically arresting.

As I’ve written before, concentration circuits are like deep work jet fuel:

they get you away from your normal energy-draining office routines,

they give your mind the sustained freedom from context switches needed to dive deep into a single problem, and

they leverage visual and environmental novelty to help shake loose new insights.

At the same time, they provide a reminder that elite-level knowledge work is about creating things with your brain — not just shuffling messages and writing PowerPoints — and that this activity, when isolated and supported, is massively rewarding.

Most important: they’re also a lot of fun.

A Recent Circuit

Anyway, two weeks ago I found myself down near the Capitol to tape an appearance on the Federalist Radio Hour. At the time, I was working on a tricky result.

I decided I would take advantage of the early spring weather to build an epic, Washington D.C.-themed concentration circuit.

Here are some of the locations I visited that morning…

I pride myself in finding the most secluded possible benches in otherwise crowded places. The above bench, where I started my day, was tucked into quiet corner not far from the Capitol building.

To shake things up, I then spent some time in a simulated jungle within the National Botanical Garden’s massive greenhouse. This certainly met the “novelty” requirement.

(A little known but important fact: the Botanical Garden has the nicest public bathrooms in D.C. — marble counters, and fresh orchids at every sink.)

I then retreated to the basement of the National Gallery to type up some of my notes. I like working in their cafe which is at the end of the mind-bending Multiverse installation shown above.

Finally, I ended my deep work session at one my favorite secret locations. Nestled in a quiet corner beyond the elevators on the third floor of the Native American History museum is a pair of comfortable leather chairs arranged by a wall of floor to ceiling windows.

Final Thoughts

Knowledge work doesn’t have to devolve into a soul-draining slurry of email and meetings. Creating things with your brain can be incredibly satisfying — but sometimes a dramatic change of scenery is needed to remind yourself of this reality.

#####

A note to my UK readers: a UK audiobook version of Deep Work is now available for pre-order. You can also hear a clip here.

(Capitol photo by Ed Schipul; Multiverse photo by NCinDC)

March 28, 2016

From Productivity to Workflow Engineering

The Ford Transformation

The craftsmen hand-building cars at the Ford Motor Company’s Piquette Avenue assembly plant in the first decade of the 20th century were, among other things, impressively productive at their tasks.

Two or three workers would gather around each partially-assembled car, taking parts, checking their fit, adjusting them on a metal lathe as needed, then checking the fit again, and so on. To watch them work would be to watch experts practiced in their movements and efficient in their tool use.

But as we now know, this productivity was irrelevant, as their approach to the work as a whole was sub-optimal.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, Henry Ford perfected his assembly line model and combined it with a commitment to producing interchangeable parts.

This new workflow was less natural, required significant capital investment, and introduced many new logistical headaches: but it also unleashed a level of value production that the old method of car construction could never match — no matter how skilled or efficient its practitioners.

Beyond Productivity

This story illustrates a division that I think will come to occupy an increasingly important role in the knowledge economy: the difference between productivity and workflow engineering.

To understand this difference, let’s begin with a key definition.

A workflow describes describes a general means or approach by which a professional goal is pursued.

(For example, in the Ford case study, in the early years of the company the primary workflow for car construction centered on a dedicated team hand-adjusting and assembling the relevant parts of a specific car.)

Productivity focuses on executing a given workflow more efficiently.

Workflow engineering, by contrast, focuses on optimizing the general means through which the relevant goal is pursued. It is defined by a willingness to make radical and inconvenient changes if the ends justify the means.

For example…

A team of computer programmers making their intra-company communication more efficient by adopting real time tools like Slack, and perhaps even integrating the tools into their code editors so they can reply to missives without switching applications, is an example of standard productivity thinking.

Realizing that programmers produce much better code if you minimize cognitive context switches, and therefore eliminate their email and Slack accounts altogether to ensure deeper work, is an example of workflow engineering.

Similarly, to draw from an earlier case study, media entrepreneur Pat Flynn hiring a high-priced executive assistant to help him answer reader email more efficiently is an example of standard productivity thinking.

Fellow media entrepreneur Brett McKay instead simply removing his email address from his web site and replacing it with a PO Box address is an example of workflow engineering.

The goal with workflow engineering is not to maximize convenience or to minimize cost and disruption. It is instead to start from a blank slate and ask: “if my goal is X, what is the absolutely most effective way to get there?”

This, in turn, requires a willingness to consider major, annoying, complicated changes if you have evidence that they’ll end up helping you ship a hell of a lot more metaphorical cars.

Workflow engineering is a concept I’m still toying with, but I think it has the potential to capture well the differences in my thinking regarding the future of work as compared to how most experts tend to talk about getting more things done.

Stay tuned…

March 21, 2016

The Case Against Email Strengthens

A Modest Proposal

Last month, I wrote an intentionally provocative article for the Harvard Business Review’s website. It was titled, “A Modest Proposal: Eliminate Email.”

The article starts by conceding that email, as a technology, is not intrinsically bad. The weed that’s currently strangling knowledge work is instead the workflow enabled and prodded by the presence of this tool.

As I expanded:

Accompanying the rise of this technology was a new, unstructured workflow in which all tasks — be it a small request from HR or collaboration on a key strategy — are now handled in the same manner: you dive in and start sending quick messages which arrive in a single undifferentiated inbox at their recipients. These tasks unfold in an ad hoc manner with informal messages sent back and forth on demand as needed to push things forward.

This workflow, I argued, leads inevitably to a state where constant email checking, during work hours and beyond, become necessary to keep the wheels of progress turning. And this state, in turn, is transforming knowledge workers into exhausted human network routers who are producing at a fraction of their cognitive capacity.

I concluded:

Given the tangled relationship between email and our current approach to work, however, it’s also clear that [a transformation to a better workflow] is almost certainly going to require a radical first step: to eliminate email.

Revealing Responses

What’s interesting to me about this discussion is less the details of my argument, but instead readers’ reactions.

The following quote from a commenter summarizes well a standard response:

I agree with the article about the evils of email. However, to attempt to outlaw email now is like trying to bolt the barn door after the horse has bolted – it’s just not gonna work.

Implicit in this observation is the belief that knowledge work depends on a large amount of digital communication. Indeed, for many, it’s hard to even conceive a concept of their “work” which doesn’t center on an inbox.

But then I read this article, which summarizes a recent research study conducted by the fabulous Gloria Mark (whom I recently met during an NPR taping), Stephen Voida, and Armand Cordello.

The study took 13 employees at a government research facility, each working for a different team, including both managers and non-managers, and asked them to quit email for a full week.

Spoiler: nothing bad happened.

Indeed, not only did they avoid bad outcomes, the employees felt happier, achieved more deep work states, experienced less stress, and moved a lot more.

This study is important because it underscores a point that was once obvious but has become less so recently: there is a difference between your work and communicating about your work.

You can make drastic changes to the latter without impeding the former.

Put another way, just because we’re used to spending most of our day communicating about our work, doesn’t mean that all this communication is really that vital.

The employees in the above experiment not only still accomplished their work without constant messaging, but actually did the work better and enjoyed it more.

This is just one study and a small sample at that. But even still, it builds my confidence that perhaps my Harvard Business Review proposal is less modest than I at first thought, and is instead one that’s growing inevitably toward a status of unavoidable.

(Photo by Amanda Tetrault)

March 11, 2016

Seneca on Social Media

Seneca on the Myth of Free

In Letter 42 of his Epistulae morales ad Lucilium, Seneca touches on the hidden costs of seemingly “free” pursuits. In doing so, he offers to his correspondent — Lucilius, the procurator of Sicily — a warning that resonates strongly today:

Our stupidity may be clearly proved by the fact that we hold that “buying” refers only to the objects for which we pay cash, and we regard as free gifts the things for which we spend our very selves.

These we should refuse to buy, if we were compelled to give in payment for them our houses or some attractive and profitable estate; but we are eager to attain them at the cost of anxiety, of danger, and of lost honour, personal freedom, and time; so true it is that each man regards nothing as cheaper than himself.

(– From Letter 42, Paragraph 7 of the Richard Gummere translation)

Over a billion people currently use Facebook — many at the cost of anxiety, lost honor, personal freedom, and certainly time. If asked why, however, many would reply, “why not?”

The service is free, conventional wisdom tells us, so no matter how minor the benefits (which tend to orbit around a generalized fear of missing out), they’re still more substantial than the cost.

But as Seneca points out, this assessment is misguided because it ignores the human toll of social media.

Unless we find value in our personhood, our attention autonomy, and our potential for real connection and creation, we’ll continue to be pushed around by media companies who convince us to throw this all away for trinkets.

(For a concrete alternative to this state of affairs, see Rule #3 from Deep Work, which details an approach to tool selection which forces you to consider the role of a new digital service in the full picture of a life well-lived before it can claim your time and attention.)

Until then, it seems, as Seneca warned Lucilius: each man truly does regard nothing as cheaper than himself.

(Hat tip: Steve A. / photo source)

February 15, 2016

Write an Attention Charter

Ambiguous Distraction

In the war to reclaim your attention, some battles have clearer fronts than others. It has become clear to me that these differences matter.

Social media, for example, is digital nicotine. It’s engineered to hook you so you can be sliced and diced into advertising fodder. It’s not worth losing your cognitive autonomy over — unless your job depends on it, you should probably quit.

But the real issues seem to arise not from the obvious whimsies, but instead from the commitments that are less obviously harmful, and in fact, in the right dose, might actually be vital.

Consider, for example…

an invitation to speak at a compelling conference,

a request to hop on a call with an interesting person,

a long email asking a question you know something about,

an offer to collaborate on a project that fits your interests, or

a new service that might make parts of your working life better.

To place a blanket ban on such activities would induce a monasticism that would likely stall your career, or, at the very least, make it unbearably monotonous.

(Even my deep work idol, Neal Stephenson — who has no public email address, and only ventures into public for book launches — ended up involved in a sword fighting video game and consults for an augmented reality pioneer.)

And yet, in my own experience, I find that the occasions when I most despair about the tattered state of my schedule are almost always the result of the accumulation of a dozen yeses that each made perfect sense in isolation.

So how do you balance these competing concerns?

The Attention Charter

It’s this question that has driven me recently to consider the potential of what we might call an attention charter.

The idea is simple…

An attention charter is a document that lists the general reasons that you’ll allow for someone or something to lay claim to your time and attention. For each reason, it then describes under what conditions and for what quantities you’ll permit this commitment.

For example…

You might decide that for you to consider attending a conference it must have at least three speakers whose topic really interests you, and then, among the conferences that meet this criteria, enforce a hard cap on attending no more than two per year.

You might decide that you’ll only allow one call per month with someone you don’t know.

You might decide that you can make one major change to the technologies you use (apps, gadgets, websites) per season.

You might decide to fix in advance the slots you’re available for work meetings (and, by doing so, solidify all the other times as those when you’ll be working deeply), and then when a request comes in from a colleague or collaborator you don’t want to reject, you can reply: “sure, here’s all the times I’m available this month: pick one.”

My model for this idea is Harvard computer scientist Radhika Nagpal. In my new book, I profile how she became a full professor while avoiding the overwork that most junior faculty assume is necessary to progress.

At the core of her strategy was something like an attention charter that helped her figure out how to stay involved in necessary professional activities without ceding full control of her time and attention.

Among other declarations, she placed a hard limit on the number of papers she would review per year and the number of times she would travel to give talks or attend conferences.

A Hard Limit

The reason I suspect strategies like an attention charter work, is that it acknowledges that certain time fragmenting activities are necessary, but it gives you the hard limits you need to engage in these activities without losing control.

It’s hard to say “no” to a reasonable request without providing yourself a good reason. An attention charter gives you that reason.

I’m still monkeying around with my own attention charter. In other words, you’re hearing about an idea before I’ve even had a chance to try it. But I think there’s something lurking here that’s important for those of us whose battle against distraction is both unavoidably important and unavoidably nuanced.

(Photo by storebukeebruse)

#####

A semi-related note that I wanted to share. I recently did a podcast interview with Barry Carter. As we were about to record, he told me about how the ideas from my book helped him double his reading speed. Anyway, he recently posted an article about how this happened. A great case study.

January 26, 2016

The Mind is Like a Locomotive

Deep Thwings

Charles Franklin Thwing is a largely forgotten but impressive figure from the early twentieth century. He graduated Harvard in the 1870s, entered seminary, became a pastor in Massachusetts, then an academic, eventually ending up president of Western Reserve University.

Charles Franklin Thwing is a largely forgotten but impressive figure from the early twentieth century. He graduated Harvard in the 1870s, entered seminary, became a pastor in Massachusetts, then an academic, eventually ending up president of Western Reserve University.

He came to my attention because of a book he wrote in 1912 titled, Letters from a Father to his Son Entering College. In this insightful volume is the following wisdom:

“To save time, take time in large pieces. Do not cut time up into bits…The mind is like a locomotive. It requires time for getting under headway. Under headway it makes its own steam. Progress gives force as force makes progress. Do not slow down as long as you run well and without undue waste. Take advantage of momentum. Prolonged thinking leads to profound thinking.”

Thwing, it seems, was a disciple of deep work a century before the term was coined. Good ideas, I suppose, are timeless.

#####

Hat Tip to Morry, who turns 80 next month, and who brought this book to my attention. Morry, inspired by Thwing, has followed this advice for decades by deploying 4 hour stretches of deep work to get important things done.

The Killer App of the Knowledge Economy

A Deep Diversion

I wanted to share some brief updates about how my new book, Deep Work, is faring since its release a couple weeks ago. It seems to have hit a nerve. This excites me — not just because it’s good news for my book, but because I think it points to a bigger shift in our cultural conversation. People seem increasingly ready to move past self-deprecating humor about how they check their phone too much, and instead seek concrete changes that will improve their cognitive life.

I wanted to share some brief updates about how my new book, Deep Work, is faring since its release a couple weeks ago. It seems to have hit a nerve. This excites me — not just because it’s good news for my book, but because I think it points to a bigger shift in our cultural conversation. People seem increasingly ready to move past self-deprecating humor about how they check their phone too much, and instead seek concrete changes that will improve their cognitive life.

Anyway, here are some highlights from the book launch:

The book debuted as a Wall Street Journal bestseller and was selected as one of Amazon’s best business & leadership books for the month of January.

The New York Times wrote: “As a presence on the page, Newport is exceptional in the realm of self-help authors…”

The Wall Street Journal called the book: “engaging and substantive…”

The Economist wrote: “deep work is the killer app of the knowledge economy…”

The Globe and Mail wrote: “This is a deep, not shallow, book, which can enrich your life…”

800-CEO-READ named Deep Work the best business book of the week and wrote: “[Newport presents] a wonderfully entangled, intertwined, and erudite series of strategies, philosophies, disciplines, and techniques to sharpen your focus and dive deep into your work.”

If you want to learn more, read my original post about the book launch. In addition, my publisher has posted two long excerpts. The first is about how deep work helps make you massively more productive and the second tackles the inanity of open offices.

I am, of course, most grateful for your support here over the years as I developed these ideas. I can’t thank you enough.

Now back to our regularly scheduled programming…

January 17, 2016

Email Zero Is Easier Than Inbox Zero

The Attack of the Inbox

Not long ago, I was listening to Pat Flynn’s podcast. Pat is an excellent podcaster, so it doesn’t take much to convince me to listen, but this time I was particularly interested because the episode title caught my attention: 9000 Unread Emails to Inbox Zero.

Pat tells the story about how his email inbox grew along with the success of his online brand. He used to try to empty his inbox. After a while, he began to consider “only” 100 unread messages as a victory. Then, one day, he looked up and his inbox had expanded to 9000 unread messages.

Something had to give.

Pat’s solution was radical: he hired a highly-trained executive assistant who could devote many additional hours to sorting through the communication deluge before it reached Pat. He still spends a lot of time on email, but at least now it’s tractable.

Longtime readers will not be surprised to learn that the subtext of this story depresses me.

I am, as you know, a big proponent of deep work — as I think this activity can produce a professional life that’s both successful and deeply meaningful. But as Pat’s experience seems to attest, our current digital economy has perverse incentives: forcing you, it seems, to fragment your time into increasingly small, anxious slivers as recognition for your skill grows.

To me, the idea of needing to hire assistants to increase the amount of one-to-one communication you can fit into a single day is, to steal a relevant phrase from George Packer, a truly “frightening vision of the future.”

But then Brett McKay came along and gave me hope…

The Deep Life of Brett McKay

Brett and his wife Kate run the Art of Manliness (AOM) website and Brett hosts the accompanying podcast (which is a favorite of mine). AOM is famous for its smart, detailed, and above all, long posts on fascinating topics.

Brett and Kate sometimes spend weeks researching just a single article. It’s a site, in other words, that built its success on a foundation of deep work.

Which is why I was not at all surprised (though relieved) when Brett recently revealed to me, in a podcast interview about my new book, their unorthodox strategy for dealing with the massive flow of emails that their popular site used to generate.

Here’s a screenshot from their contact page:

Brett mentioned that before they removed their email address from their site, the time he spent answering emails — like Pat also experienced — become unwieldy. Eliminating that task freed up massive mental resources.

I asked him whether this shift away from a publicly available email address hurt the traffic to his site.

“It didn’t make a difference,” he replied.

This case study warms my heart.

We spend so much time figuring out better ways to filter, automate, outsource and otherwise manage the sources of seemingly mandatory distraction in the digital age that we forget to step back and ask whether these distractions really need to be in our lives in the first place.

(Photo by Lisa Leggio)

January 5, 2016

The Book Facebook Doesn’t Want You to Read

A Focus Opus

It’s official, today is the release of my new book, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World.

It’s official, today is the release of my new book, Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World.

The book argues that deep work (focusing without distraction on a cognitively demanding task) is becoming more valuable in our economy at the same time that it’s becoming more rare.

The implication: if you’re one of the few to take advantage of this trend and cultivate a deep life, you’ll thrive.

Not only will you produce at quantity and quality levels that stun your peers, you’ll also find your work more meaningful and less exhausting.

To make this claim more concrete, consider me as a case study. As a longtime devotee to depth, I’ve been able to publish close to 50 peer-reviewed papers as an academic (earning over 2500 citations), write five books as an author (selling over 200,000 copies), and build a popular blog (300,000 page views last month) — all without working at nights and rarely working on weekends. The secret is my fanatic commitment to deep work.

This highlights an important point that I want to emphasize: This book isn’t a cranky screed about how kids these days spend too much time on the Facebook, and it isn’t a collection of warmed over suggestions about how you should turn off notifications on your phone and not check email first thing in the morning.

It instead calls for a radical transformation to your work life in which focusing with great intensity becomes your core activity, not an occasional indulgence.

With this in mind, the book then details specific strategies, divided among four “rules,” that you can use to accomplish this transformation — covering topics from focus training, to effective scheduling, to rituals and routines, to aggressive tactics for taming the tide of shallow obligations that constantly threaten to drown the typical knowledge worker’s day.

Give Yourself the Gift of Depth

To help you learn more about the book, I’ve included below an annotated table of contents and a link to a long excerpt.

In the meantime…

If this topic sounds interesting to you — whether you’re a longtime reader of my writing or new to the party — please consider buying a copy of this book.

If you already bought the book and found it useful, please consider buying copies for your friends or colleagues (if you do buy multiple copies, send me an email so I can thank you personally).

I’m proud of this book and believe it can have an impact on how we think about work in a digital age.

Deep Work is available now at Amazon (kindle and hardcover), Audible, Barnes and Noble, IndieBound, or anywhere else books are normally sold.

Annotated Table of Contents

The book is divided into two parts. The first part makes the case for deep work, while the second part teaches you how to become better at this skill.

(Note: An extended excerpt from Chapter 1 is available here.)

Introduction

In the introduction, I define the key terms deep work and shallow work and then detail the deep work hypothesis summarized above. I also tell the story of my own history with depth, starting with my arrival as a new graduate student at the Theory Group at MIT and continuing until the present day.

PART 1: THE IDEA

Chapter 1: Deep Work is Valuable

In this chapter, I make the argument that deep work is like a super power in the new economy, as it allows you to learn hard things quickly and produce output at high levels of quality and quantity. (Read an excerpt.)

Chapter 2: Deep Work is Rare

In this chapter, I address the elephant in the room: if deep work is so valuable, then why are so many organizations encouraging behaviors that discourage it (e.g., open office plans, constant connectivity, mandatory social media use)? I introduce the ideas of The Principle of Least Resistance, Busyness as a Proxy for Productivity, and The Cult of the Internet to help explain this self-defeating trend.

Chapter 3: Deep Work is Meaningful

In this final chapter of Part 1, I draw from neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy to make the argument that deep work is intrinsically satisfying and provides a much more meaningful work experience than jumping frenetically from one shallow task to another.

PART 2: THE RULES

Rule #1: Work Deeply

This rule details multiple strategies for regularly making time for deep work in your schedule and getting the most value out of these sessions. Among other things, you’ll learn how to find a philosophy for scheduling depth that fits the constraints of your particular job, how to build effective depth rituals, and how and why to implement shut down routines for the end of your day.

Rule #2: Embrace Boredom

This rule details multiple strategies for training your ability to concentrate. It’s motivated by the claim that focus is a skill that must be developed before you can do it with any effectiveness. Among other things, you’ll learn why it’s more important to schedule distraction than to schedule focus, how to meditate productively, and why you should approach your work like Teddy Roosevelt.

Rule #3: Quit Social Media

This rule details multiple strategies for aggressively limiting the sources of carefully-engineered distraction in your life. A core idea of this rule is that most people select digital tools using the any benefit mindset, which claims that you should use a tool if it can provide any benefit. This rule argues that you should instead use the craftsman mindset in which you only select the tools that provide the most substantial benefits to the things you find most important. Or, to simplify greatly: vastly fewer people should be using Facebook.

Rule #4: Drain the Shallows

This rule details multiple strategies for reducing the number of shallow obligations in your professional life and then tackling those that remain with much greater efficiency. The motivating idea for this rule is that if you have too many shallow obligations on your plate, you’ll have no time or energy left for the deep work that really matters. Among other things, you’ll learn why you should negotiate a deep-to-shallow work ratio with your boss, why you’ll get more done if you stop working at 5:30 each day, and how to significantly reduce the time you spend in your email inbox.

Conclusion

I conclude the book with an unexpected take on Bill Gates’s rise to success (hint: he’s really good at deep work), and a final pitch for the value of a deep life as compared to the increasingly exhausting, and increasingly fruitless, swirl of shallow busyness that’s so common today.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers