Cal Newport's Blog, page 38

September 29, 2016

Nassim Taleb’s (Implied) Argument Against Social Media

Fooled by Shiny Apps

Nassim Taleb’s Fooled by Randomness is a classic in the genre of erudite idea books. It’s an extended discussion of the many different ways humans misunderstand the role of probability in their everyday lives.

The book is most famous for its attack on the role of skill in money management (Malcolm Gladwell called the book the Wall Street equivalent of Luther’s ninety-nine theses), but it touches on many other topics as well.

As a reader named Rainer recently reminded me, Taleb also includes a passage quite relevant to the dominant role new technologies like social media, or Apple watches, or the latest, greatest smartphone app play in modern life (see if you can sight the 1990’s-era Michael Lewis reference):

“The argument in favour of ‘new things’ and even more ‘new new things’ goes as follows: Look at the dramatic changes that have been brought about by the arrival of new technologies…Middlebrow inference (inference stripped of probabilistic inference) would lead one to believe that all new technologies and inventions would likewise revolutionize our lives. But the answer is not so obvious: Here we only see and count the winners, to the exclusion of the losers…I hold the opposite view. The opportunity cost of missing a ‘new new thing’ like the airplane and the automobile is minuscule compared to the toxicity of all the garbage one has to go through to get these jewels.”

In other words, the mere possibility that a new technology might prove important to your life should not be enough to motivate you to adopt it.

People who are driven by the fear of missing out or the dream of early adopter superstardom are deploying a “middlebrow inference” that examines only the maximum possible return, not the value derived in expectation.

It’s the rejection of such thinking that has led me to continue to abstain from Facebook and Twitter, among other popular pastimes in the rapidly evolving digital attention casino.

I’ll sign up for those new new things only once their expected value resolves to something significant enough to compete with the activities I already know pay out.

Both Taleb and I would urge you to consider the same…

######

Study Hacks is sponsored in part by Blinkist: a subscription service that provides you access to an archive of detailed summaries of important nonfiction books. I often use it to determine which books are worth buying (like Fooled by Randomness) and which don’t deserve further attention. To find out more and receive a subscription discount click here.

September 20, 2016

Quit Social Media

Anti-Social Grumblings

I recently gave a deliberatively provocative TEDx talk titled “quit social media” (see the video above). The theme of the event was “visions of the future.” I said my vision of the future was one in which many fewer people use social media.

Earlier this week, Andrew Sullivan published a long essay in New York Magazine that comes at this conclusion from a new angle.

Sullivan, as you might remember, founded the sharp and frenetic political blog, The Daily Dish (ultimately shortened to: The Dish). The blog was a success but its demands were brutal.

For a decade and a half, I’d been a web obsessive, publishing blog posts multiple times a day, seven days a week…My brain had never been so occupied so insistently by so many different subjects and in so public a way for so long.

In recent years, his health began to fail. “Did you really survive HIV to die of the web?”, his doctor asked. Finally, in the winter of 2015, he quit, explaining: “I decided, after 15 years, to live in reality.”

This might sound like an occupational hazard of a niche new media job, but a core argument of Sullivan’s essay is that these same demands have gone mainstream:

And as the years went by, I realized I was no longer alone. Facebook soon gave everyone the equivalent of their own blog and their own audience. More and more people got a smartphone — connecting them instantly to a deluge of febrile content, forcing them to cull and absorb and assimilate the online torrent as relentlessly as I had once. Twitter emerged as a form of instant blogging of microthoughts. Users were as addicted to the feedback as I had long been — and even more prolific.

As he summarizes: “the once-unimaginable pace of the professional blogger was now the default for everyone.”

As I noted in my talk, one of the most common rationales for social media use is that it’s harmless — why miss out on the interesting connection or funny ephemera it might occasionally bring your way?

Sullivan’s essay is a 6000 word refutation of this belief. Social media is not harmless. It can make your life near unlivable.

Sullivan attempts to end with a note of optimism, saying “we are only beginning to get our minds around the costs,” before adding a more resigned coda: “if we are even prepared to accept that there are costs.”

I agree that we’re not yet ready to fully face this reality, and cheeky TED talks by curmudgeonly young professors like me probably won’t move the needle. But when heavyweights like Sullivan join the conversation, I can begin to feel a cautious optimism grow.

September 13, 2016

On Deep Breaks

A Break to Discuss Breaks

After last week’s post on attention residue, multiple readers have asked about taking breaks during deep work sessions. These questions highlight an apparent tension.

On the one hand, in my book on the topic and here on Study Hacks I often extol the productive virtue of spending multiple hours (and sometimes even days) in a state of distraction-free deep work. As I emphasized last week, these sessions need to be truly free of distraction — even quick glances at your inbox, for example, are enough to significantly reduce your cognitive capacity.

On the other hand, in my Straight-A book (published, if you can believe it, almost exactly a decade before Deep Work), I recommend students study in 50 minute chunks followed by 10 minute breaks. I cite some relevant cognitive science to back up this timing. Similar recommendations are also made by adherents to the pomodoro technique, which suggests short timed bursts of concentration partitioned by breaks.

Which idea is right?

Deep Breaks

The short answer to the above question: both.

Deep work requires you to focus intensely on a demanding task. But few can maintain peak cognitive intensity for more than an hour or so without some sort of relief.

This relief is necessary. But it’s also dangerous.

Most types of breaks you might take in this situation will wrench your attention away from the task at hand and leave you with a thick slather of attention residue.

If you’re careful, however, it’s possible to take a so-called deep break which will allow your mind a chance to regroup and recharge without impeding your ability to quickly ramp back up your concentration.

Anyone who regularly succeeds in long deep work sessions is almost certainly someone skilled at deploying deep breaks to keep the session going without burning out or losing focus.

There’s no single description of what constitutes a deep break, but here are some useful heuristics from my own experience:

Deep breaks should not turn your attention to a target that might generate a professional or social obligation that you cannot completely fulfill during the break (e.g., glancing at an email inbox or social media feed).

Deep breaks should not turn your attention to a target that your mind associates with time-consuming distraction rituals (e.g., many people have a set “cycle” of distracting web sites they visit when they surf that has become so ingrained that looking at one site sends their mind the message it’s time to look at them all).

Deep breaks should not turn your attention to a related, but not quite the same, professional task (e.g., if you’re trying to write a report, and you turn your attention to quickly editing an unrelated report).

Deep breaks should not turn your attention to a topic that is complicated, stressful and/or something that will sometime soon need a lot of your attention.

Deep breaks should not usually last more than 10 – 15 minutes, with some exceptions, such as for meals.

Breaks that avoid the above warnings should probably be okay. For example, here are some of my standard deep break activities:

Taking a short walk to get more water or coffee while trying to just observe my surroundings.

Day dreaming about the good things that could come from succeeding with the deep work task at hand (e.g., when working on a proof, I might day dream about how I would describe the result if I ended up publishing it).

Summarizing to myself what I already know about the task at hand and what I’m trying to accomplish.

Reading a book chapter or magazine article that has nothing to do with the deep task at hand.

If I’m working at home, doing something fun with my boys (who, fortunately for me, rarely bring up distributed algorithm theory when we play).

Complete a household task or short errand.

I don’t want to be too rigid in my description of these breaks. The key message is that when it comes to deep work, you shouldn’t feel like you’re required to maintain peak concentration for hours on end. (If you try to, you’ll fail.) On the other hand, be mindful about how you take your cognitive breathers as they play a key role in whether the deep work session as a whole will succeed.

#####

Thank you to the 200 – 300 people who showed up last night to listen to Scott and I discuss learning strategies. I enjoyed the discussion and your questions. If you missed the webinar, but want to learn more about Scott’s new rapid learning course (which was the inspiration for the event), you can visit the course website.

(Photo by Ghislain Mary)

September 9, 2016

Join Me and Scott Young for a Live Conversation on Learning and Study Skills on Monday at 8:30 pm ET

Update: For those who asked about this, Scott’s Rapid Learner course website is now live. You can learn more about the course here. (Even if you’re not interested in the course, scroll down to the before and after pictures from Scott’s 30 day portrait drawing challenge. Crazy!)

A Learned Chat on Learning

My good friend Scott Young is finally about to launch his long promised Rapid Learner online course, which teaches you how to learn hard things quickly. This is something that Scott knows a lot about (c.f., his astonishing MIT Challenge).

To help Scott spread the word about his course, I agreed to join him for a free live webinar on Monday, September 12, at 8:30 pm Eastern time (to attend, sign up here).

We’re going to discuss learning and study skills and then take questions on these topics from the live webinar audience. At the end of the seminar, Scott will then explain his course and make a pitch for it.

A couple details…

I want to emphasize that this is not my course. It’s Scott’s course. I’m joining this webinar to help him spread the word (because it’s good content, Scott’s a good friend, and I thought it would be fun to talk about study skills with a live audience), but I don’t want anyone to end up enrolling in this course under the misunderstanding that I’m somehow involved in the course itself or its content.

As far as I know, there will be not be a recorded version of the webinar available for those who missed it.

Join Me and Scott Young for a Live Conversation on Learning and Study Skills on Monday at 8:30 ET

A Learned Chat on Learning

My good friend Scott Young is finally about to launch his long promised Rapid Learner online course, which teaches you how to learn hard things quickly. This is something that Scott knows a lot about (c.f., his astonishing MIT Challenge).

To help Scott spread the word about his course, I agreed to join him for a free live webinar on Monday, September 12, at 8:30 Eastern time (to attend, sign up here).

We’re going to discuss learning and study skills and then take questions on these topics from the live webinar audience. At the end of the seminar, Scott will then explain his course and make a pitch for it.

A couple details…

I want to emphasize that this is not my course. It’s Scott’s course. I’m joining this webinar to help him spread the word (because it’s good content, Scott’s a good friend, and I thought it would be fun to talk about study skills with a live audience), but I don’t want anyone to end up enrolling in this course under the misunderstanding that I’m somehow involved in the course itself or its content.

As far as I know, there will be not be a recorded version of the webinar available for those who missed it.

September 6, 2016

A Productivity Lesson from a Classic Arcade Game

The Distracted Gamer

A reader recently shared with me an interesting observation from his own life.

To provide some context, this reader is a fan of the classic arcade game snake (shown above). This game is hard: as your snake grows, it requires an increasing amount of concentration to avoid twisting back on yourself and ending the round.

What this reader noticed was that whenever he paused the game for a quick interruption (e.g., answering a text or talking to someone who walked into the room), he became significantly more likely to fail soon after returning to play.

These arcade struggles might not sound that surprising, but they turn out to be a great example of a psychological effect that every knowledge worker should know about: attention residue.

The Most Important Theory You’re Ignoring

The research literature on attention residue, which was pioneered by business professor Sophie Leroy, reveals that there’s a cost to switching your attention — even if the switch is brief.

When you turn your attention from one target to another, the original target leaves a “residue” that reduces cognitive performance for a non-trivial amount of time to follow.

This was likely the effect that was tanking my reader’s arcade performance: when he switched his attention to the new target presented by an interruption, and then back to his game, the resulting attention residue reduced his cognitive performance and therefore his game play suffered.

As I argued in Deep Work, this effect can have a profoundly negative impact on knowledge worker productivity.

In more detail, most knowledge workers who claim to single task are actually primarily working on one thing at a time, but punctuating this work with a frequent series of just checks (quick glances at text messages, email inboxes, slack channels, social media feeds, etc…just in case something important has arrived).

This type of pseudo-focus might seem better than old school multitasking (in which you try to work on multiple primary tasks simultaneously), but attention residue theory teaches us that it might be just as bad.

Each one of those just checks shifts your attention. Even if this shift is brief (think: twenty seconds in an inbox), it’s enough to leave behind a residue that reduces your cognitive capacity for a non-trivial amount of time to follow.

Similar to our reader from above losing his ability to play snake at a high level, your ability to write/code/strategize at a high level is significantly diminished every time you let your attention drift.

If, like most, you rarely go more than 10 – 15 minutes without a just check, you have effectively put yourself in a persistent state of self-imposed cognitive handicap. The flip side, of course, is to imagine the relative cognitive enhancement that would follow by minimizing this effect.

To put this another way: if you commit to long blocks without any interruption (not even the quickest of glances), you’ll be shocked by how much sharper and productive you feel.

August 30, 2016

Technology Alone Won’t Make You Better at What You Do

Some Insights from a Geek’s Heresy

I recently began reading Kentaro Toyama’s 2015 book, Geek Heresy: Rescuing Social Change from the Cult of Technology.

To provide some background, in 2005 Toyama cofounded Microsoft Research India, which focused on applying technology to social issues. He then left for academia where he began to study such efforts from an objective distance. Geek Heresy describes what he found.

I’m only through around 100 pages, but so far Toyama’s conclusions have been bracing.

He leverages a blend of research and firsthand experience to dismiss the cult-like belief (common in Silicon Valley) that hard social problems can be solved with the application of the “right” technology (an illustrative target of Toyama’s critique is Nicholas Negroponte’s belief in the power of cheap laptops to cure all that ails the developing world).

For the purposes of this post, however, I want to highlight a powerful observation detailed in Chapter 2. It’s here that Toyama introduces what he calls the Law of Amplification, which he defines as follows:

[T]echnologies primary effect is to amplify human forces. Like a lever, technology amplifies people’s capacities in the direction of their intentions.

As Toyama elaborates, you cannot expect a technology to transcend existing social forces or transform existing intentions; it tends instead to amplify whatever tendencies are already in place; c.f., social media, which instead of transforming us into a newly informed global community, supercharged our existing biases for gossip, self-aggrandizement, and easy distraction.

It seems to me that among many applications, this “law” is quite relevant for understanding some of the issues concerning technology in the workplace that I’ve been grappling with over the past few years.

Consider, in particular, my favored target of the moment: workplace email.

To understand email’s impact in the context of this law we need to step back and understand the forces at play right before this tool’s arrival.

Fortunately, we can get an insightful look at this period in another book I recently read, Leslie Perlow’s 1997 treatise, Finding Time: How Corporations, Individuals, and Families Can Benefit from New Work Practices, which describes nine months Perlow spent observing software developers in a Fortune 500 company.

Finding Time paints a picture of a pre-email workplace in which many of the problems that define our current age are incipient. Managers interrupt workers constantly to check in and unexpectedly shift priorities. There’s little structure to how the day unfolds, and in its place are an atmosphere of crisis, fragmented time, long hours, and a sense of very little “real” work getting done.

(Interestingly, later in the study, Perlow ends up convincing the developers to deploy prescheduled deep work blocks into their day — to much success.)

The arrival of email into the workplace was generally accepted by our culture as a good thing. Making communication faster and people more accessible, it was argued, should only increase options and opportunity (which, as Kevin Kelly explains, is What Technology Wants).

According to Toyama’s Law of Amplification, however, this new technology should instead be expected to amplify the types of existing intentions and trends Perlow documented.

Which is exactly what it did.

As I mentioned in a recent post, digital communications certainly did simplify some existing processes in a positive manner. But it’s main impact has been to take the culture of crisis and interruption Perlow found bubbling below the surface in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and erupt it into the new, stress-inducing whirlwind that defines 21st century knowledge work.

To step back: Toyama’s book primarily addresses the folly of assuming technology in isolation can solve social problems. But I’m arguing that this warning also applies to the world of work.

As the history of email teaches us, a new technology, no matter how slick, cannot by itself transform a workplace for the better. This remains a deeply human endeavor. We must figure out what it means to work well in the 21st century and then slot in technologies only where and how they fit this plan. These tools cannot do this hard work for us.

August 25, 2016

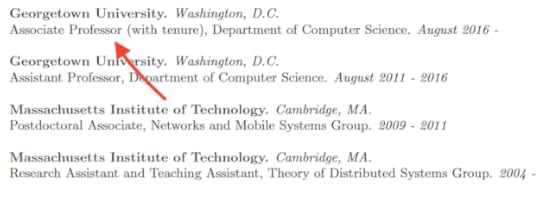

A Brief Note on Tenure

I don’t like talking about myself (outside discussions of hyper-specific productivity techniques), so I’ll keep this announcement brief…

At some point early on in my graduate student career I set two somewhat arbitrary goals for my academic trajectory: to become a professor by the age of 30 and tenured by the age of 35.

I ended up starting at Georgetown at the age of 29, and earlier this summer I earned tenure at the age of 33 (though I since turned 34).

There are many factors that help fuel an academic career, and many fell outside my direct control.

But reflecting on these past five years, it’s easy for me to identify what was by far the highest ROI activity in my professional life: deep work.

I know I’ve said similar things a million times before. And it’s not sexy. And it’s not a contrarian “hack.”

But in my case, focusing intensely on hard things that people unambiguously value, day after day, week after week, was more or less the whole ball game.

August 21, 2016

Email is Most Useful When Improving a Process that Existed Before Email

Connectivity Contradictions

Recently, I’ve been collecting stories from people who held the same type of job before and after the introduction of email. Something that struck me as I sorted through these recollections is their variety.

Email was a miracle to some.

For example, I talked to a woman who has spent many years in mergers and acquisitions. These deals, it turns out, require large contracts to be received and sent with urgency at unexpected times.

Before email, this meant weekends camped out at the office.

“If I was expecting a new version of a merger agreement, I would have to stand outside the fax room waiting for my 200-page document and then call to ask the other side to re-fax any missing pages,” my source recalled.

“If there was even a possibility that I would be needed, it made no sense to go home…people would sleep at the office.”

With email, these same urgent documents could suddenly reach her anywhere — greatly reducing time wasted squatting by the warmth of a fax modem and increasing time with her family.

“Email has been a plus,” she concludes.

But email was also a curse to many others.

One teacher I spoke with, for example, told me about how the arrival of email made teachers at her school suddenly available to parents in a way they never had been before.

The school eventually instituted a policy that all such emails must be answered within 48 hours.

“Email exploded,” my source recalled. “My planning period was spent reading and answering emails…forget planning. [It became] a huge distraction from the already very difficult job of teaching.”

A Useful Heuristic

How do we make sense of these contradictions?

As I sorted through more stories like the above an interesting pattern emerged.

Email seems to be at its best when it directly replaces a professional behavior or process that existed before email’s rise.

For example, in mergers and acquisitions, the urgent and hard to predict delivery of complicated contracts has long been a necessary and important behavior. Sending these documents by email is much easier than relying on fax machines.

On the other hand, email seems to be at its worst when it helps instigate the sudden arrival of a new behavior or process that didn’t exist before.

In teaching, for example, pre-email parents didn’t have nor did they expect ubiquitous access to their children’s teachers. There was no pressing pedagogical or parental need for such access.

Once teachers got email addresses, however, this new behavior emerged essentially ex nihilo and began to cause problems.

On reflection, this heuristic makes sense…

If a behavior or process has been around for a long time in a given profession, it probably serves a useful purpose. Therefore, if a technology like email can make it strictly more efficient/easy, then it’s a clear win.

By contrast, when email helps instigate a new behavior or process, this development tends to occur in a bottom up fashion. That is, no one identifies in advance the new behavior or process as being something that’s useful — it’s instead driven by in-the-moment convenience and happenstance. (For more on this idea of unguided emergence see Leslie Perlow’s discussion of “cycles of responsiveness” in Sleeping with Your Smartphone .) This is not a great way to evolve professional practices, so we shouldn’t be surprised that the results are often exhausting and counterproductive to those forced to live with them.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t develop new behaviors and processes in our professional lives. But we should be wary of those that emerge without our explicit consent. Email, in this accounting, should be a source of concern not because it’s intrinsically bad, but because it’s so easy and convenient that it tends to encourage the emergence of these new unguided and often draining behaviors.

August 2, 2016

On Primal Productivity

A Primal Movement

The primal/paleo philosophy argues that we’d all be better off behaving more like cavemen.

In slightly more detail, this school of thought notes that humankind evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to thrive with a paleolithic lifestyle. The neolithic revolution, which started with agricultural, and quickly (in evolutionary timescales) spawned today’s modern civilizations, is much too recent for our species to have caught up.

By this argument, we should look to paleolithic behavior to shape our basic activities such as eating, exercising, and socializing. To eat bread, or sit all day, or center our social life on a small electronic screen, is to fight our genetic heritage.

Or something like that.

This philosophy attracts both righteous adherents and smug critics. And they both have a point.

I maintain, however, that this type of thinking is important. Not necessarily because it’s able to credibly identify “optimum” behaviors, but because it poses clear thought experiments that are worthy of discussion.

An Interesting Thought Experiment

It’s with this spirit of exploration in mind that I pose the following prompt: what would the primal/paleo movement have to say about productivity?

I’m no paleoanthropologist, but pulling from a common sense understanding of this era, I would point toward the following three dictums as a reasonable approximation of what it might mean to work like a caveman:

Rule #1: Work on one thing intensely with plenty of rest surrounding this effort.

Rule #2: Develop an expert skill/craft from which your status and value to the tribe is primarily derived.

Rule #3: Work closely with a small team oriented toward the same goal, with outside communication nonexistent or rare.

Of course, this is all somewhat pie in the sky, but what strikes me about this thought experiment is how far modern knowledge work has drifted from how we likely spent hundreds of thousands of years approaching our daily labor.

For those interested in the concept of workflow engineering, questions like the above are important. It’s not that we can figure out exactly how paleolithic man functioned, nor would we want to follow that script precisely in the modern era.

But this thought experiment forces us to confront, and ultimately justify, the mismatch between how we’ve been wired over the eons to function and the recently emerged and somewhat arbitrary work patterns of the digital age.

#####

If you’re interested in reading detailed summaries of the top books on these primal paleo ideas (such as this and this and this), consider trying out Study Hack’s sponsor Blinkist — my new secret weapon for quickly figuring out which books are worth my time and attention.

(Photo by Steve Schroeder)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers