Cal Newport's Blog, page 34

August 19, 2017

Are We Going to Allow Smartphones to Destroy a Generation?

The iGen Problem

Many people recently sent me the same article from the current issue of The Atlantic. It’s titled, “Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?”, and it’s written by Jean Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego State University.

The article describes Twenge’s research on iGen, her name for kids born between 1995 and 2012 — the first generation to grow up with smartphones. Here’s a short summary of her alarming conclusions:

“It’s not an exaggeration to describe iGen as being on the brink of the worst mental-health crisis in decades. Much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

I won’t bother describing all of Twenge’s findings here. If you’re interested, read the original article, or her new book on the topic, which comes out this week.

The point I want to make instead is that in my position as someone who researches and writes on related topics, I’ve started to hear this same note of serious alarm from multiple different reputable sources — including the head of a well-known university’s mental health program, and a reporter currently bird-dogging the topic for a major national publication.

In other words, I don’t think this growing concern about the mental health impact of smartphones on young people is simply nostalgia-tinged, inter-generational ribbing.

Something really scary is probably going on.

My prediction is that we’re going to see a change in the next 2 – 5 years surrounding how parents think about the role of smartphones in their kids’ lives. There will be a shift from shrugging our shoulders and saying “what can we do?”, to squaring our shoulders and asking with more authority, “what are we going to do?”

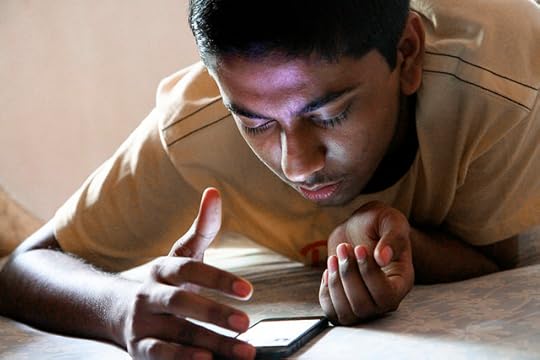

(Photo by Pabak Sarkar)

August 13, 2017

How I Read When Researching a Book

The Reading Writer

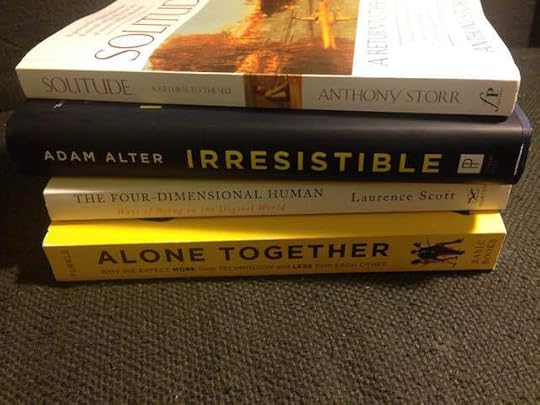

As a writer I’m required to read lots of books, especially when ramping up a new project, as I am now. The picture above, for example, shows the books I’ve purchased only in the past two days.

I’ve already finished one of them.

My approach to the books I process in my professional life is quite different than my approach to the books I savor in my personal life. The former requires the ruthlessly efficient extraction of key ideas and citations, while the latter unfolds as a slower, more romantic endeavor.

I thought it might be interesting to briefly reveal the method I’ve honed over the years for my professional reading. It’s simple, and the basics should sound familiar to any serious nonfiction reader, but it has served me well.

Here’s the strategy:

I read with pencil in hand. Recently I’ve been using Ticonderoga #2 soft lead pencils as their footprint on the page is pleasingly gentle. But the writing implement doesn’t really matter, and I’ll fall back on a brutish ballpoint Bic if that’s all that happens to be available.

When I find a passage I want to remember, or an allusion or citation I might need, or a stylistic approach that catches my attention: I mark it in the margin.

Sometimes I scribble a few notations if I want to ossify a non-obvious observation or insight about what I’m marking.

Then — and this is the key optimization — I cross the corner of the page with a clear line.

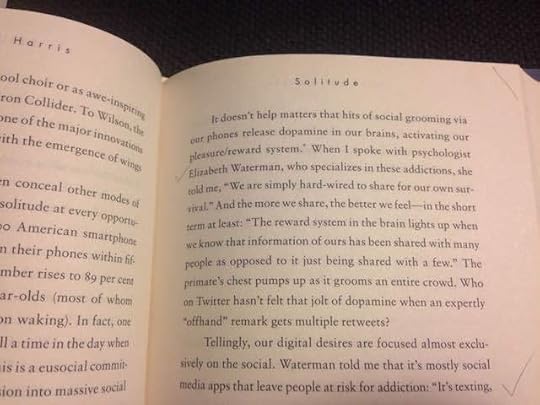

Here, for example, is a recently read page from Michael Harris’s book Solitude (which, interestingly enough, is different than Anthony Storr’s 1988 classic of the same title which I just acquired today). Notice the mark in the upper right corner that indicates a few interesting citations below have been identified for potential further review:

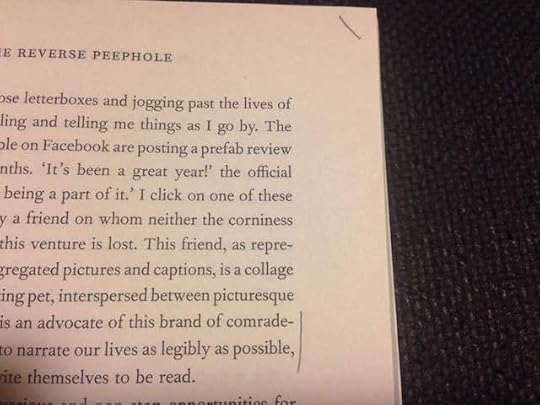

Here’s another example from Laurence Scott’s The Four-Dimensional Human. Once again, a mark in the corner identifies the page as relevant, and a scratched line below highlights a passage that captures an idea useful to my purposes:

The key to my system is the pencil mark in the page corner. This allows me later to quickly leaf through a book and immediately identify the small but crucial subset of pages that contain passages that relate to whatever project I happen to be working on.

My copy of Scott’s book, for example, has around 30 pages marked (I just counted). It will take me less than 10 minutes to review in totality the elements of this treatise that are potentially relevant.

(To emphasize the obvious, this doesn’t mean that Scott’s book only contained 30 pages that interested me: it’s a complicated and interesting work of literary techno-social criticism — which came close to winning the Samuel Johnson Prize two years ago — that I found thought provoking throughout. These are just the number of pages that happened to be relevant to what I’m working on at the moment.)

When it comes to my research process, this is about as complicated as it gets — at least with repect to how I process relevant books. As I work on a new writing project, a growing number of volumes fill the shelf next to my desk, each marred with intentional pencil scratches. When I think I need a particular source, I pull it from the shelf and after a brief review of my ad hoc annotations find myself fully engaged with what it has to offer.

Simple. But effective.

August 8, 2017

Aziz Ansari Quit the Internet

The Disconnected Life

Aziz Ansari recently deleted the web browser from his phone and laptop. He also stopped using email, Twitter and Instagram.

As he explained in an interview with GQ, when he gets into a cab, he now leaves his phone in his pocket and simply sits there and thinks; when he gets home, instead of “looking at websites for an hour and half, checking to see if there’s a new thing,” he reads a book.

Here’s how he explains his motivation:

“Whenever you check for a new post on Instagram or whenever you go on The New York Times to see if there’s a new thing, it’s not even about the content. It’s just about seeing a new thing. You get addicted to that feeling. You’re not going to be able to control yourself. So the only way to fight that is to take yourself out of the equation and remove all these things.”

He was worried when he first deleted his web browsers that he would suffer from not being able to look things up. He soon stopped caring.

“Most of the shit you look up, it’s not stuff you need to know,” he explains.

The journalist interviewing Ansari for GQ reacts to this answer with incredulity. “What about important news and politics?”, he asks.

“Guess what?”, Ansari replies. “Everything is fine! I’m not out of the loop on anything. Like, if something real is going down, I’ll find out about it.”

Later in the interview, however, after covering a variety of topics, the interviewer makes a harsh observation:

“I have to be honest, my man. I’m surprised at how sad you sound…You don’t seem like someone who has the world by the balls, you know?”

Ansari provides a surprisingly honest (if perhaps excessively testicular) reply:

“I got the world by the balls professionally. Personally, I’m alone right now…So right now, I have it by the balls, but I’m feeling it slowly going away and I’m worried about finding new balls.”

Highlighted in this conversation is a fundamental complexity of our current moment.

Escaping the fizzy chatter of the online world can support deep insight and creative achievement (c.f., the reviews for the second season of Master of None).

But life without persistent digital distraction can also be lonely, and stark, and, frankly, require a lot more work to satisfy the human need for novelty and connection.

Ansari, in other words, perhaps encapsulates both the highs and lows of a committing to a deep life in a distracted world.

(Photo by Vincent Anderlucci)

#####

On a related note, I just finished reading Michael Harris’s new book, Solitude: In Pursuit of a Singular Life in a Crowded World. It provides a thoughtful investigation of several similarl issues (I was particularly taken by Harris’s final chapter, which was beautifully written).

July 24, 2017

Top Performer is Now Open

Top Performer is an eight-week online career mastery course that I developed with my friend and longtime collaborator Scott Young. It helps you develop a deep understanding of how your career works, and then apply the principles of deliberate practice to efficiently master the skills you identify as mattering most. Over the past four years we’ve had over two thousand professionals go though this course, representing a wide variety of different fields, backgrounds, and career stages.

We open the course infrequently for new registrations (usually twice a year). It’s that time again: the course is open for registration this week (the registration closes Friday at midnight Pacific time).

If you’d like to learn more about the course, how it works or whether it’s right for you,* see the registration page here.

If you have any questions about the course, Scott’s team will be happy to answer them here: support@scotthyoung.zendesk.com

#####

* To emphasize the obvious: the course is definitely not for everyone. It’s expensive and targeting those at a stage in their career where they’re able and willing to invest more seriously in advancement. I might send one or two additional notes about the course this week, but will then return to my regularly scheduled programming.

July 20, 2017

On Claude Shannon’s Deliberate Depth

An Insightful Life

Claude Shannon is one of my intellectual heroes.

His MIT master’s thesis, submitted in 1936, laid the foundation for digital circuit design. (My MIT master’s thesis, submitted 70 years later, has so far proven somewhat less influential.)

His insight was simple. The wires, relays and switches that made up the types of complex circuits he encountered at AT&T could be understand as the terms and operators of logic statements expressed in the boolean algebra he encountered as a math major at the University of Michigan.

Though simple, this insight had huge impact. It meant that circuits could be designed and optimized in the abstract and precise language of mathematics, and then transformed back to soldered wires and finicky magnetic coils only at the last step — enabling staggering leaps in circuit complexity.

But he wasn’t done. A decade later, inspired in part by his wartime research efforts, Shannon developed information theory: a mathematical framework that formalizes both techniques and fundamental limits for reliably transmitting information over noisy channels.

(For a popular treatment of this theory, see this or this; for a technical introduction, I recommend this guide).

Put another way, Shannon’s master’s thesis laid the foundation for digital computers, while his information theory paper laid the foundation for digital communication.

Not a bad legacy.

Decoding Shannon’s Work Habits

This is all to say that I was, quite naturally, excited to learn that my friend Jimmy Soni was co-authoring a big new biography of Shannon.

The resulting book came out earlier this week (I read a review copy — it’s great). As part of the publicity surrounding the release, Soni wrote an epic article on the twelve lessons he learned from the years he spent researching Shannon. The title of the first lesson caught my attention: “cull your inputs.”

To quote Soni:

“[D]istractions are a permanent feature of life, in any era, and Shannon shows us that shutting them out isn’t just a matter of achieving random bursts of focus. It’s about consciously designing one’s life and work habits to minimize them.”

Shannon, we learn, often worked with his door shut at Bell Labs to ward off distraction.

“None of Shannon’s colleagues, to our knowledge, remembered him as rude or unfriendly,” Soni writes, “but they do remember him as someone who valued his privacy and quiet time for thinking.”

It’s not that Shannon avoided collaboration. If anything, he was known for his ability to maintain stimulating conversation for hours when the topic was right. But he was wary of less fruitful digressions.

Shannon also discarded much of his voluminous incoming correspondence and invitations into a box labeled: “Letters I’ve Procrastinated On For Too Long.” When Soni and his co-author studied Shannon’s correspondence at the Library of Congress, they found “far more incoming letters than outgoing ones.”

To summarize these observations somewhat flippantly, while it’s absolutely true that Shannon’s breakthroughs ultimately enabled Facebook (which, of course, depends on computers and networks), if he was alive today, he’d almost certainly not use it.

July 13, 2017

When Slower Communication Enables Faster Growth

The Rule of Five

This morning I listened to Srini Rao interview Sarah Peck. Though most of the interview focuses on Peck’s personal life, toward the end they discuss her work as a business consultant.

During this segment, Peck mentioned an interesting heuristic I hadn’t heard before (I’m paraphrasing here): relying only on unstructured communication — e.g., just give everyone an email address or shared Slack channel and then rock and roll — works fine in organizations with five or less employees, but once you grow larger there is too much communication for people to comfortably keep track of everything just in their heads.

At this size, Peck notes, organizations need to introduce systems to document communication and to support structured decisions. It’s no longer enough to simply let emails and chats fly, and hope everything works out. You need more detailed and careful approaches to how people work.

This transition toward structure, of course, can be painful. Here’s Peck:

“It’s super frustrating for start-ups, because what they’re used to, their history, their knowledge of what it means to be their business is that they can move fast and break things and they can just reach out to anybody, and all of the sudden you add constraints, and it can piss people off.”

But adding constraints to how people communicate and make decisions is absolutely necessary. As Peck summarizes: “You have to move a little slower before you can move fast.”

I was intrigued by this discussion because it underscores something I’ve noticed in my research on effectiveness in an age of digital connectivity. A major (unspoken) defense of a hyperactive hivemind workflow based on constant disruptive messaging is that any other alternative would be inconvenient, and “frustrating,” and probably “piss people off.”

I like Peck’s (implicit) response to this concern: too bad. Valuable work is not always easy to produce.

#####

Speaking of valuable work, my friend Ryan Holiday, who is also, in many ways, my hero (he lives on a quiet ranch with a library-sized collection of books), has a great new book coming out next week titled: Perennial Seller. It’s an inside look at the hard but rewarding task of producing work that stands the test of time. I read a galley copy: I’m 100% on board with Ryan’s thinking on this topic. Check it out.

June 27, 2017

John Carmack’s Deep Nights

Late Night Depth

I recently reread Masters of Doom — David Kushner’s entertaining (though cheesily dialogued) history of id Software.

Something new caught my attention this time through the book.

Kushner revealed that id’s ace coder, John Carmack, adopted an aggressive tactic to increase his effectiveness while working on his breakthrough Quake engine: Carmack, seeking a break from distraction, began to shift the start of his workday one hour at a time, until eventually he was starting his programming in the evening and finishing before dawn.

The uninterrupted depth provided by this odd habit allowed Carmack (with help from graphics guru Michael Abrash) to reinvent electronic entertainment with the first lightening fast, fully 3D PC game engine.

I mention this example because I think it supports my prediction that high impact computer programming will be one of the first places we start to see a major revolt from the standard knowledge work approach of spending most of your day tending inboxes and chat channels. For the Carmacks of the world, the value of what they can produce if left to operate at full cognitive capacity (Quake sold 1.8 million copies), far outweighs the inconveniences of them becoming hard to reach.

These initial revolts will be important — not because we will want to mimic the exact habits they produce, but because they’ll help spread the idea that how we work in the knowledge sector is much more flexible than we might currently imagine.

June 20, 2017

An Early 20th Century Lesson on the Difference Between Convenience and Value

The Pullman Problem

A couple years ago, I stumbled across a series of articles from 1916, published in a business journal called System. The articles detail how the Pullman Company (famous for their eponymous train cars) arrested their slide away from profitability by systematically overhauling their operations.

As I detail in an essay I wrote for Fast Company, a big factor in Pullman’s early 20th century problems would sound familiar to early 21st century ears: communication overload.

As Pullman president, John Runnells, explained, many departments were run with “confusing unrelated systems [that] had been spontaneously developed.”

The result is that everyone was a little involved in everything — disrupting their ability to do their primary work.

If you wanted something from the brass works, to cite an example given in the 1916 articles, you would go over to the brass works and bother someone you knew until you got what you wanted– distracting both of you from your main value-producing crafts.

As Runnells sagely observed, if you don’t build optimized systems to handle logistics, the effort simply gets offloaded, in an ad hoc and disruptive manner, to everyone: “and every man contributing by that much [to these organizational efforts] demoralized his own particular work by the interruption.”

A Century-Old Problem

This of course is the same problem faced by many modern knowledge work organizations. We hook up to email addresses and Slack channels and then just rock n’roll with messages all day long, trying to work things out on the fly, and hoping busyness will transmute into value.

This need to constantly monitor an inbox brimming with ad hoc messages, in other words, is simply the Pullman brass workers’ dilemma magnified to a new extreme by the electronic efficiency of digital networks.

Which is all to say that we should take seriously the solution Runnells and his team successfully deployed to turn around their company’s flagging fortunes: they made communication harder and less convenient.

As I detail in the Fast Company article, among other things, Runnells hired many more managers to do nothing but handle the logistical issues that used to distract the skilled factory workers. He also barred the door to the brass works to outsiders: if you needed something, you had to fill out a relevant form and send it through a special slot for a dedicated manager to process.

Hiring the managers was expensive.

Barring the doors was inconvenient.

But it was worth it: Pullman’s profit per train car jumped by over $100.

In today’s world, we assume faster communication and more convenient collaboration will always help the bottom line. We would be smart, however, to keep in mind the lessons learned by yesterday’s business leaders: making things harder isn’t necessarily bad.

June 6, 2017

Mike Rowe on Efficiency versus Effectiveness

Insights from Dirty Jobs

Earlier this week, I listened to Brett McKay’s interview with Mike Rowe. As you’ll learn if you listen to the conversation, following his stint as the host of Dirty Jobs, Rowe has become an advocate for the trades.

In this interview, as in many others, Rowe argues that skilled labor (think: plumbing, welding) can be both satisfying and lucrative, and yet there are still somewhere around three million such jobs left unfilled in this country. He credits this gap largely to a contemporary culture that demonizes blue collar work and preaches the best path is always a college degree, followed, God willing, by a pair of Warby Parker glasses and a job as a social media brand manager.

(I might have added that last part.)

I always find Rowe’s thoughts on shifting American work cultures interesting, but there’s a phrase he often uses in these discussions that has recently begun to draw my attention: efficiency versus effectiveness.

Rowe notes that knowledge work seems obsessed with efficiency, while the skilled trades seem more concerned with effectively solving problems (c.f., his infamous TED talk on sheep castration).

The former can be dehumanizing, while the latter tends to be satisfying.

Stepping away from the immediate context of Rowe’s advocacy, I think he has touched on an important point here that highlights a little-discussed problem rotting the core of the knowledge economy…

The Failure of Techno-Productivism

Those who work with information have become obsessed with what I sometimes call techno-productivism: the idea that introducing technologies that simplify or speed up certain work tasks will necessarily make you or your organization increasingly more productive.

(Note, I use “productive” here in the true economic sense of producing more value per labor hour invested.)

Techno-productivism is intuitive. But it has also been, in my opinion, a failed ideology.

By focusing relentlessly on making specific tasks or operations easier and faster, instead of stepping back and trying to understand how to make an organization as a whole maximally effective, we’ve ended with a knowledge work culture in which people spend the vast majority of their time trying to keep up with the very inboxes, devices and channels that were conceived for the exact opposite purpose — to liberate more time for more valuable efforts.

Instead of striving for the embodied effectiveness of the skilled craftsman, in other words, we’ve ended up a twitching hyperactive mess of unstructured communication.

Rowe hints at an interesting path out of this swamp: stop lionizing efficiency, and start asking the question that has guided craftsmen for millennia: what’s the most effective way for me to accomplish the things that are most important?

(Photo by gato-gato-gato)

#####

Speaking of effectiveness, I want to pitch a kickstarter, initiated by a friend of mine, that just launched this week: Mouse Books. The concept is elegant: important and compelling works of literature delivered in a pocket size printing, roughly the size of an smartphone. When you feel the urge for distraction, instead of pulling out your phone, you can pull out a Mouse book and read something meaningful. This is cat nip for Study Hacks fans. Check it out…

May 22, 2017

John Grisham’s 15-Hour Workweek

The Deep Life of John Grisham

As longtime readers know, I enjoy tracking down the deep work habits of well known and highly accomplished individuals. This is why I was happy to recently stumble across a pair of interviews (here and here) in which the novelist John Grisham describes his professional routines.

Here’s what I learned…

Grisham primarily writes his novels during the winter months on his farm in Oxford, Mississippi. During this period he works five days a week, starting at 7 am and typically ending by 10 am.

Grisham writes in a period outbuilding on his property that used to house an antebellum summer kitchen. He and his wife refurbished the kitchen to maintain its period details (with the main exception being that they added electricity and air conditioning). Crucially, as Grisham explains: “[the building has] no phone, faxes, or internet. I don’t want the distraction. I don’t work online. I keep it offline.”

Grisham maintains strict rituals for his writing. He starts work on a novel on the same day each year, and starts writing each day at the same time. He works on the same computer. He drinks the same type of coffee out of the same cup. “My office routine rarely varies,” he explains. “It’s pretty structured.”

Grisham starts a new novel on January 1st and is usually done with the bulk of the writing by the end of March. He aims to be completely done with the manuscript by July. This leaves a nice half year period to recharge and work on new ideas.

What I like about Grisham’s deep work habits — beyond the obvious romanticism of writing in a refurbished period farmhouse outbuilding — is that the novels that support his astoundingly successful and lucrative writing career require only 15 hours a week, 6 months out of the year.

This example underscores what I think is one of the most compelling attributes of deep work: it can produce a massive amount of value in a relatively small amount of time.

#####

Unrelated Note: My friend Eric Barker, who is arguably one of the best (and certainly one of the most productive) science-based advice writers in the business, just released his first book: Barking Up The Wrong Tree (which includes a guest appearance by myself — so you know it must be good). I highly recommend checking it out.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers