Cal Newport's Blog, page 33

November 2, 2017

Arnold Bennett’s Fight Against Steampunk Social Media

How to Live

In 1910, Arnold Bennett published a short volume titled How to Live on 24 Hours a Day. He was alarmed with the way the newly emergent British middle class seemed to waste their time outside of work. The average salaryman of this era doesn’t live, he noted, but instead “muddles through,” wasting time — that “inexplicable raw material of everything,” the supply of which “though gloriously regular is cruelly restricted.”

Bennett being Bennett decided he could tell these muddlers how to live better. So he wrote this guide.

I come back to this book from time to time. If you look past the standard Bennett snobbery and occasional dash of Victorian ornateness — “inexplicable raw material of everything”…really? — it’s both surprisingly pragmatic and relevant to all sorts of contemporary issues.

In my latest skim, for example, the following passage caught my attention. It’s Bennett’s summary of the standard post-work evening for a British white collar worker:

“You don’t eat immediately on your arrival home. But in about an hour or so you feel as if you could sit up and take a little nourishment. And you do. Then you smoke, seriously; you see friends; you potter; you play cards; you flirt with a book; you note that old age is creeping on; you take a stroll; you caress the piano…. By Jove! a quarter past eleven. You then devote quite forty minutes to thinking about going to bed; and it is conceivable that you are acquainted with a genuinely good whisky. At last you go to bed, exhausted by the day’s work. Six hours, probably more, have gone since you left the office…”

To Bennett, these six wasted hours (“gone like magic, unaccountably gone!”) are a tragedy. What caught my attention about this vignette, however, is that he seems to be describing, in essence, an early-twentieth century version of killing time by messing around on your phone — it’s steampunk social media.

This interpretation is important because it underscores something I often overlook when I chastise people about mindless digital tinkering: this attraction toward the mindless is not new, but instead something that we’ve been struggling with since the initial introduction of leisure time.

Learning to live, then as now, is hard work.

I mention this not to offer a definitive solution, but to remind myself that the depth I preach, both in work and personal affairs, is not a default mode subverted only recently by new technology. It is instead an aspirational goal that requires intention, practice, and perhaps even some wisdom from an antiquated British social critic.

With this in mind, if you’re looking for some concrete ideas about how to train your mind for more substantive fare, you could do worse than to consider the following intriguing suggestion from Bennett: take just 90 minutes, only three nights a week, and dedicated them toward a quality pursuit.

“If you persevere [with this habit],” he writes, “you will soon want to pass four evenings, and perhaps five, in some sustained endeavour to be genuinely alive.”

October 26, 2017

Segment’s Systematic Quest for Depth

Segment’s Focus Problem

Segment is a typical Silicon Valley success story. It’s a data analytics software company started by three MIT dropouts in 2011. Last year it raised $64 million in its Series C funding round.

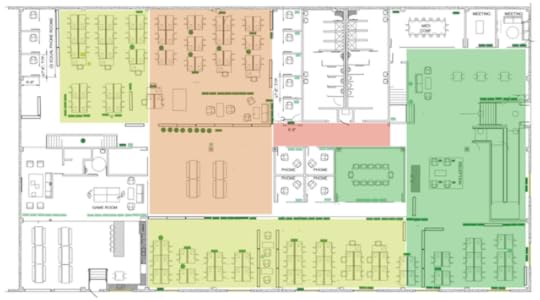

Things at Segment, in other words, were going well — with one exception: their employees were having a hard time focusing. Concerned, the company ran an internal team survey and discovered that the “chatter and noise” in their industry-standard open office was the biggest cause of distraction (not surprisingly, “group slack channels” was the second biggest cause) .

So Segment decided to do something about it.

In a move that you could only expect from an advanced data analytics company, they programmed an iOS app to measure office noise levels and ran it on the iPads mounted outside the office’s conference rooms. They then crunched the resulting data and found that some parts of the office were more noisy than others, with the loudest areas around a factor of two louder than the quietest (see above image, in which red corresponds to loud and green to quiet).

Armed with this data, they rearranged the seating in their open office. As they described on their company blog:

“The teams needing the most verbal collaboration — Segment’s sales, support, and marketing teams — moved to the naturally louder parts of the office. The teams needing the most quiet — engineering, product, and design — moved to the quietest parts of the office.”

They then re-ran their original survey and discovered that the total time people spent focusing increased from 45% to 60%. As they explained: “In a purely numerical sense, you could equate that to hiring 10–15 people.”

The Focused Future

What I like about this story is that the company identified the ability to focus as a tier one skill (indeed, they list it as one of their four “core values”), and then made concrete, data-driven changes to better support it.

In recent years, when interviewed about my writing, I often predict that a transformation away from our current ad hoc, noisy, distracted way of working into something much more structured and effective is not only inevitable, but will happen fast once it gets going.

When you see a company like Segment essentially find 15 free employees by rearranging their desks to support more deep work, you get a glimpse of the type of humble experiments that will spark a major revolution.

######

My friend Rob Montz is an incredibly talented, up and coming documentary filmmaker based out of DC. On Wednesday (Nov. 1st), he’s hosting a sneak preview screening of his new documentary short, “The Quarterlife User Manual,” which, in his words, “lays out the core rules a newly minted college grad should follow to secure a meaningful job.” It also features yours truly, among many other more famous subjects. If you’re interested in seeing the sneak peak (which will be held in We Work — Manhattan Laundry, in the Columbia Heights neighborhood of DC), send an email to robmontz@gmail.com to request a spot on the guest list…I only ask that you applaud loudly whenever I appear on screen.

October 19, 2017

Andrew Wiles on the State of Being Stuck

A Persistent Answer

Ben Orlin is a math teacher who publishes the clever essay blog, Math with Bad Drawings. Last year, Orlin had the opportunity, during a press conference at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum, to ask a question of Andrew Wiles, the Princeton Professor (now at Oxford) who in 1994 finally solved Fermat’s Last Theorem.

As Orlin reports on his blog, he asked the following:

“You’ve been able to speak to an unusually wide audience for a research mathematician. What are some of the themes you’ve tried to emphasize when talking to a broader public?”

Wiles’s answer, according to Orlin, can be summarized in six words: “Accepting the state of being stuck.”

As Wiles elaborated, research mathematics unfolds as follows:

“You absorb everything about the problem. You think about it a great deal—all the techniques that are used for these things. [But] usually, it needs something else. So, you get stuck.”

At this point, he explains, “you have to stop…let your mind relax a bit…[while] your subconscious is making connections.”

Then you “start again.” Day after day. Week after week. Until, one day:

“You find this thing…Suddenly you see the beauty of this landscape…[before,] when it’s still some kind of conjecture, it seems really far away…[but now] it’s like your eyes are open.”

Wiles admitted that the enemy he fights against most is “the kind of message put out by, for example, the film Good Will Hunting.”

And, in particular, the idea that for some people math comes easy (Matt Damon glancing at the chalkboard, and then dashing out the solution to the impossible problem), and for all others it’s hopeless.

The reality, as Wiles knows, is that math is just plain hard. Regardless of who you are. But it’s also amazingly rewarding if you’re used to the feeling of persisting even when you have no idea about how best to move forward.

A Good Response

I liked this answer (and Orlin’s commentary on it) for two reasons.

The first is personal. As a theoretical computer science I spend a lot of my professional life stuck on math problems. It’s hard to explain to outsiders what this is like, and Wiles’s response does a good job of capturing the competing forces of frustration and joy that come from tackling such things on a regular basis.

The second has to do with my recent post about how we lack a good vocabulary for describing the varied cognitive efforts that comprise deep work. Wiles’s answer is a good step toward filling in some of those blanks.

#####

For more on Andrew Wiles’s attack on Fermat’s Last Theorem, see Simon Singh’s popular book, Fermat’s Enigma. For a more raw and technical treatment of what it’s like to do Fields Medal-caliber math, see the more recent Birth of a Theorem. The image above is taken from Wile’s proof, as it appeared in the Annals of Mathematics.

(Hat tip: Amin)

October 6, 2017

Jony Ive’s iConcern

Ive’s iConcern

At last week’s New Yorker TechFest conference, superstar Apple designer Jony Ive took the stage.

At some point during the presentation, Ive was offered a softball question about the ways the iPhone has changed the world. Ive’s response was surprising: “Like any tool, you can see there’s wonderful use and then there’s misuse.”

Asked what he meant by “misuse,” Ive responded: “perhaps, constant use.”

The fact that Jony Ive, the guy who designed the iPhone, is worried about the way people engage his creation, emphasizes an important point: there’s something broken about our current relationship with our technology.

Our culture was quick to accept the idea that we’d end up checking these things constantly. We shrug our shoulders and laugh about life in these modern times.

But Ive’s small statement sends a big message: you don’t have to accept this.

(Image by Kempton)

#####

When US Marine Akshay Nanavati returned from Iraq he struggled with fear. But instead of giving in to the negative forces dragging him down, he turned his life around. In his new book, FEARVANA, Nanavati tells his story and explains how anyone can follow his path in overcoming hard things in life. I was honored to blurb this book. If this topic resonates, find out more here.

October 1, 2017

Are You Using Social Media or Being Used By It?

A Social Experiment

If you, like many people, use social media and generally agree that it’s an important technology, try the following experiment.

Take out a piece of paper and list your most important uses for these services — the activities that social media is well-suited to provide and that unambiguously enrich your life. This list, for example, might include items like:

The ability to see new photos of your nephews, nieces, or grandchildren.

The Facebook Group used to run a local organization you belong to.

The hashtag that keeps you up to date with the latest news from an activist movement that you support.

The social media industrial complex* likes to point to lists like these to justify its importance. “It would be crazy to dismiss our technology,” they cry, “look at all these useful things people do with it!”

But here’s the second part of the experiment: estimate honestly how much time it would take per week to satisfy these important uses. In my experience, for most people, the answer is around 15 – 30 minutes.

And yet, the average American adult social media user spends two hours per day on these services, with almost half this time dedicated to Facebook products alone.

This is the disconnect that the social media industrial complex doesn’t want you to notice. They want the conversation to stop at the assertion that social media isn’t useless, and then hope people move on without questioning the specific role these services have claimed on their limited and valuable time and attention.

The social media business model depends on this oversight.

To be more concrete, I claim that most users could probably reap 95% of the value they get out of social media by signing in twice a week, on a desktop or laptop, to catch up on the latest photos, or check their organization’s group, or to browse the most recent chatter relevant to a movement they care about. Let’s called this controlled use of these services.

Social media companies cannot reach multi-billion dollar valuations, or return consistent stock growth to their investors, based on controlled use. What they need is compulsive use, which is what happens when you launch the app on your phone with some important goal in mind, and then thirty minutes later look up and realize you’ve been snagged into an addictive streak of low-value tapping, liking, and swiping.

As former Google employee and whistleblower Tristan Harris explains, these companies carefully engineer their products — especially the versions readily available through apps on your phone — to exploit psychological weak spots to trap you into compulsive use. For example:

The “like” button? This was added to inject more intermittent reinforcement into the social media browsing experience — significantly increasing the amount of times people check their accounts.

The ability to “tag” people in your posted photos? The primary purpose of this feature (which, when considered objectively, is really pretty arbitrary) is to create a new stream of social approval indicators — something our tribal brains are evolved to take deadly seriously, and therefore induces people — surprise, surprise — to significantly increase the amount of times they check their accounts.

With this in mind, I’m going to stop short of asking you (yet again — I was chagrined to recently learn that I’m the top two results when you google “Quit Social Media”) to consider leaving these services altogether. Instead, let me make a suggestion that the social media industrial complex fears far more: change your relationship with these services to shift from compulsive to controlled use.

Still use social media, if you must: but on a schedule; just a handful of times a week; preferably on a desktop to laptop, which tames the most devastatingly effective psychological exploitations baked into the phone apps.

You have very little to lose, as controlled use preserves all of the things you seriously value from these services, but have so much to gain when you decide there’s a better use for that extra 13.5 hours a week than helping prop up real estate prices in Northern California.

#####

* This is my somewhat facetious term for the powerful combination of the massive social media platform monopolies, and the growing sector of the knowledge tech economy — gurus, consultants, online brand managers, etc. — that depends on the belief that social media is fundamental to modern commerce and life.

September 23, 2017

Spend More Time Alone

A Lonely Binge

I recently read three books on the topic of solitude. Two were actually titled Solitude, while the third, and most recently published, was titled Lead Yourself First — which is pitched as a leadership guide, but is actually a meditation on the value of being alone with your thoughts.

This last book resonated with me in part because it was co-authored by a former Army officer and a well-respected federal appellate judge, meaning it’s written with the type of exacting logic and ontological clarity that warms my overly-technical nerd heart.

Style aside, Lead Yourself First makes many interesting points, but there were two lessons in particular that struck me as relevant to the types of things we talk about here. So I thought I would share them:

Lesson #1: The right way to define “solitude” is as a subjective state in which you’re isolated from input from other minds.

When we think of solitude, we typically imagine physical isolation (a remote cabin or mountain top), making it a concept that we can easily push aside as romantic and impractical. But as this book makes clear, the real key to solitude is to step away from reacting to the output of other minds: be it listening to a podcast, scanning social media, reading a book, watching TV or holding an actual conversation. It’s time for your mind to be alone with your mind — regardless of what’s going on around you.

Lesson #2: Regular doses of solitude are crucial for the effective and resilient functioning of your brain.

Spending time isolated from other minds is what allows you to process and regulate complex emotions. It’s the only time you can refine the principles on which you can build a life of character. It’s what allows you to crack hard problems, and is often necessary for creative insight. If you avoid time alone with your brain your mental life will be much more fragile and much less productive.

Among other impacts, these ideas provide an interesting new perspective on one of my favorite topics: deep work. Not all types of deep work satisfy this definition of solitude, as it’s possible to deeply react to inputs from other minds, such as when you’re trying to make sense of a tough piece of writing or lock into a complicated lecture.

But in general, deep thinking is time spent alone with your mind, and as such it’s just one of many different flavors of solitude — all of which aid human flourishing.

I ended my last book by claiming: “a deep life is a good life.” The authors of Lead Yourself First would rework that claim to read something like: “a life rich in solitude (both at work and at home) is a good life.” In an age where persistent reactivity is possible from the moment you wake up to the moment you fall sleep, this latter formulation is probably one worth spreading.

September 17, 2017

Approach Technology Like the Amish

Kevin Kelly and the Amish

Eight years after dropping out of college to wander Asia, Kevin Kelly returned home to America, bought an inexpensive bike, and made a meandering 5,000 mile journey across the country. As he recalls in his original and insightful 2010 book, What Technology Wants, the “highlight” of the bike tour was “gliding through the tidy farmland of the Amish in eastern Pennsylvania.”

Kelly ended up returning to the Amish on multiple occasions during the years that followed his first encounter, allowing him to develop a nuanced understanding of how these communities approach technology. As he reveals in Chapter 11 of his book, the common idea that the Amish reject all modern technology is a myth. The reality is not only more interesting, but it also has important implications for our current culture.

As Kelly puts it: “In any discussion about the merits of avoiding the addictive grasp of technology, the Amish stand out as offering an honorable alternative.”

Given such a strong endorsement, it seems worthwhile to briefly summarize what Kelly uncovered during these visits to rural Pennsylvania…

The Amish and Technology

“Amish lives are anything but anti-technological,” Kelly writes. “I have found them to be ingenious hackers and tinkers, the ultimate makers and do-it-yourselvers. They are often, surprisingly, pro-technology.”

He explains that the simple notion of the Amish as Luddites vanishes as soon as you approach a standard Amish farm. “Cruising down the road you may see an Amish kid in a straw hat and suspenders zipping by on Rollerblades.”

Some Amish communities use tractors, but only with metal wheels so they cannot drive on roads like cars. Some allow a gas-powered wheat thresher but require horses to pull the “smoking contraption.” Personal phones (cellular or household) are almost always prohibited, but many communities maintain a community phone booth.

Almost no Amish communities allow automobile ownership, but it’s common for Amish to travel in cars driven by others.

Kelly reports that both solar panels and diesel electric generators are common, but it’s usually forbidden to connect to the larger municipal power grid.

Disposable diapers are popular as are chemical fertilizers.

In one memorable passage, Kelly talks about visiting a family that uses a $400,000 computer-controlled precision milling machine to produce pneumatic parts needed by the community. The machine is run by the family’s bonnet-wearing, 10-year old daughter. It’s housed behind their horse stable.

These observations dismiss the common belief that the Amish reject any technology invented after the 19th century. So what’s really going on here?

The Amish, it turns out, do something that’s both shockingly radical and simple in our age of impulsive and complicated consumerism: they start with the things they value most, then work backwards to ask whether a given technology performs more harm than good with respect to these values.

As Kelly explains, when a new technology rolls around, there’s typically an “alpha geek” in any given Amish community that will ask the parish bishops permission to try it out. Usually the bishops will agree. The whole community will then observe this first adopter “intently,” trying to discern the ultimate impact of the technology on the things the community values most.

If this impact is deemed more negative than helpful the technology is prohibited. Otherwise it’s allowed, but usually with caveats on its use that optimize its positives and minimize its negatives.

The reason most Amish are prohibited to own cars, for example, has to do with their impact on the social fabric of the community. As Kelly explains:

“When cars first appeared at the turn of the last century, the Amish noticed that drivers would leave the community to go picnicking or sightseeing in other towns, instead of visiting family or the sick on Sundays, or patronizing local shops on Saturday. Therefore the ban on unbridled mobility was intended to make it hard to travel far and to keep energy focused in the local community. Some parishes did this with more strictness than others.”

This also explains why an Amish farmer can own a solar panel but not connect to the power grid. The problem is not electricity, it’s the fact that the grid connects them too strongly to the world outside of their local community, violating the Amish commandment to “be of the world, but not in it.”

The Original Digital Minimalists

I titled this post: Approach Technology Like the Amish. To be clear, I don’t mean that you should adopt the specific values of Amish life, as these are based primarily on their often illiberal and admittedly esoteric religious beliefs.

What I do mean, however, is that you should consider adopting their same thoughtfulness in approaching technology. The Amish are clear about what they value, and new technologies are evaluated by their impact on these values. The key is building a good life — not fretting about missing out on some minor short term pleasure or interesting diversion.

(If we held ourselves to this same standard, I suspect, many fewer people would own Apple watches.)

Later in this chapter, Kelly asks the key question: “This method works for the Amish, but can it work for the rest of us?”

He then answers: “I don’t know.”

I’m more confident than Kelly. I think something like this method can work for the rest of us, especially once you replace Amish values with your personal values, and the decree of your parish bishops with your own honest self-assessment.

In fact, I even have a name for such a philosophy: digital minimalism.

(Photo by frankieleon)

September 10, 2017

Franklin Foer on Technology’s Surprising Threat to Humanity

Contemplating the Importance of Contemplation

Franklin Foer has a new book coming out this week. It’s titled, World Without Mind: The Existential Threat of Big Tech.

I haven’t read it yet, but this morning, on returning from a family camping trip, I read Foer’s essay in today’s Washington Post and a recent interview with The Verge (as, of course, there’s no better time to contemplate the existential threat of technology than right after a weekend in the woods).

According to the interview in The Verge, Foer writes in the book: “the tech companies are destroying the possibility of contemplation.”

This premise is one I obviously support, having written an entire book on why we should fight to retain our diminishing ability for sustained attention.

But whereas my main issue with digital distraction was limited to issues of personal satisfaction and productivity, Foer, in elaborating his contemplation quote, goes much broader in his concern:

“We’re being dinged, notified, and clickbaited, which interrupts any sort of possibility for contemplation. To me, the destruction of contemplation is the existential threat to our humanity.” [emphasis mine]

In using this strong language, Foer is hitting on an increasingly urgent point that I’ve also seen fruitfully explored in Matt Crawford and Jaron Lanier’s humanist critiques of the attention economy.

Whereas I’m often focused on the immediate practical concerns of new technologies, an increasing number of thinkers like Foer, Crawford and Lanier are exploring a bigger point: when we allow ourselves to be washed away by the latest gadget or app designed to extract some more dollars from our attention, we’re not just losing some time, we’re actually losing something more fundamental about what it means to be an autonomous human.

When you hear an argument enough times, it probably makes sense to start taking it seriously.

(Photo by Alyson Hurt; this is where I was camping this weekend.)

August 31, 2017

Apple’s New Open Office Sparks Revolt

Not Open to Openness

Apple’s new Cupertino headquarters cost $5 billion (see above). One of its prominent features is a massive open office space in which many Apple engineers sit on benches at long shared work tables.

As Apple aficionado John Gruber revealed in a recent episode of his podcast, not everyone is happy with this decision.

“I heard that when floor plans were announced, that there was some meeting with Johny Srouji’s team,” said Gruber, before explaining that Srouji is an important senior vice president in charge of Apple’s custom silicon chips.

Srouji, to put it politely, was not pleased with the idea of moving his team to a cacophonous, distracting, cavernous open office.

As Gruber tells it:

“When he [Srouji] was shown the floor plans, he was more or less just ‘Fuck that, fuck you, fuck this, this is bullshit.’ And they built his team their own building, off to the side on the campus … My understanding is that that building was built because Srouji was like, ‘Fuck this, my team isn’t working like this.’”

To be clear, this story is just a rumor. But it smells right.

Designing silicon is a complicated, painstaking process that requires copious amounts of deep work. Nothing about it is helped by surrounding yourself with unrelenting disruption.

True or not, I like the broader point underscored by this rumor. In knowledge work, your primary capital investment is in human brains. If you’re not careful about the environment you setup for these brains to function in, you cannot expect a good return on investment.

To date, Silicon Valley has tried hard to ignore this reality to instead chase vague trends and embrace tired signifiers of innovation. But if more and more senior people like Srouji react by saying “Fuck this,” things will change.

#####

(Hat tip to Mike B. who pointed me toward this interview via this Silicon Valley Business Journal article.)

August 26, 2017

Toward a Deeper Vocabulary

When Writing is More than Writing

As a professor who also happens to opine publicly about productivity, I’m often invited to stop by dissertation bootcamps — a semi-annual ritual at many universities where doctoral students gather to hear advice and work long hours on their theses in an atmosphere of communal diligence.

Something that strikes me about these events is the extensive use of the term “writing” to capture the variety of different mental efforts that go into producing a doctoral dissertation; e.g., “make sure you write every day” or “don’t get too distracted from your writing by other obligations.”

The actual act of writing words on paper, of course, is necessary to finish a thesis, but it’s far from the only part of this process. The term “writing,” in this context, is being used as a stand in for the many different cognitive efforts required to create something worthy of inclusion in the intellectual firmament of your discipline.

In my own academic work, for example, these efforts include the general synthesis of trends in search of new openings, the struggle to read and understand existing papers, probing for a fresh attack on a problem, trying to work through the technical details needed to pull an argument together, and, of course, the careful grind required to write up the results clearly — each of which presents a unique mental experience and its own set of challenges.

The tendency for bootcamp attendees to sweep such varied activities together into a generic term like “writing” is a minor linguistic quirk, but I’m beginning to believe that it points to a potentially broader problem: our culture lacks a sufficiently nuanced vocabulary for discussing rigorous cognitive efforts.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, if, as Boas famously claimed, the Eskimos have dozens of words for “snow,” then in an emerging knowledge work society, we should have more than a handful of words to describe the mental efforts on which, more and more, our livelihoods depend.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers