Cal Newport's Blog, page 36

March 2, 2017

The Focused Rise of Wesley So

So Good They Can’t Ignore Him

Yesterday, Tyler Cowen published a blog post about the 23-year old chess grandmaster Wesley So. It begins: “[So] should be starring in a Malcolm Gladwell column”

As Cowen notes, just a few years ago So was seen as an up-and-coming player who lacked the strategic polish needed for elite play. Cowen was surprised to learn recently that So had risen to number nine in the world rankings. Since then, So won four top tournaments in a row including a win over world champion Magnus Carlsen.

“Arguably he is the second best player in the world,” Cowen writes, “and the one most likely to dethrone Carlsen.”

There are many explanations for So’s rise. But there’s one contributing factor, in particular, I want to emphasize. Here’s So in a recent interview:

“When I decided to try for a professional career…I thought about what I needed — more time to study and less stress. Both came immediately when I turned away from the internet.” [emphasis mine]

Not only does So restrict his internet use to email and chess game analysis, he also eschews other forms of distraction:

“There is only one cell phone in this family, and it belongs to my sister Abbey who is very capable of dealing with any unpleasantness that tries to enter through it. I have had no social media…for almost two years and I am alive, healthy and happy.”

I’m sure Wesley So has never heard the term digital minimalism, but his rise highlights an important principle of this philosophy: when evaluating new technologies there’s a difference between asking “what value can this bring me?”, and “what is its effect on the things I find most valuable in my life?”

(Photo of Wesley So by Abbey Key via Chess News; hat tip for this article idea: Ryan L.)

February 23, 2017

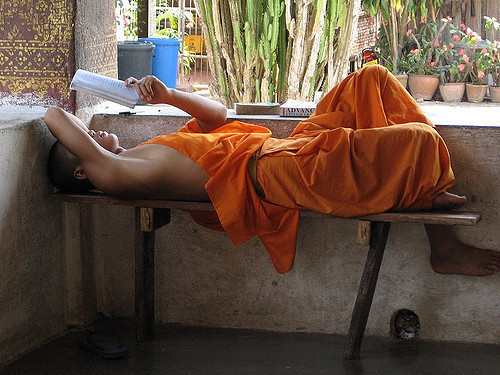

The Rise of the Monk Mode Morning

Productive Conversations

In my role as someone who writes about productivity, I enjoy the opportunity to discuss this topic with a variety of different people. Recently, something caught my attention about these conversations.

Several different accomplished people, all in distinct occasions, mentioned to me their adoption of the same bold deep work hack: the monk mode morning.

The execution of the monk mode morning is straightforward. Between when you wake up and noon: no meetings, no calls, no texts, no email, no Slack, no Internet. You instead work deeply on something (or some things) that matter.

What makes this hack particularly effective is its simple regularity. If someone wants to schedule something with you, it becomes reflexive to respond “anytime after noon.” Similarly, your colleagues soon learn not to expect you to see something they send until after lunch.

There’s no guesswork or inconsistency: everyone’s on the same page, and you make 3 to 4 hours of deep progress on valuable goals, every day.

From Theory to Practice

Clearly, spending the a.m. in monk mode is the type of hack that makes me swoon. But it’s also the type of hack that I would usually assume is not feasible for those in “normal” jobs with clients and employees and deadlines.

Which explains why it caught my attention when, as mentioned in the opening to this post, multiple different people in “normal” jobs told me that they employ the monk mode morning to great effect.

Earlier this week, for example, I was talking with a media personality who runs his own company and swears by the monk mode morning. He said: “if someone gets really upset that they can’t reach me in the morning, my first thought is that this guy is a spaz…not the type of person I want to work with.”

Not everyone is in a position to execute the monk mode morning (indeed, most of the people who mentioned this to me in recent months run their own companies). But the growing popularity of this bold hack is yet another indication that my long predicted shift away from the cult of connectivity, and toward depth, is perhaps beginning to pick up speed.

(Photo by Hanoi Mark)

February 13, 2017

Facebook Phreaks and the Fight to Reclaim Time and Attention

A Minimalist Trend

Last week, I sent a note to my email list asking readers about their personal digital minimalism strategies. I’ve only just begun wading through the more than 250 responses, but I’m already noticing an interesting trend: there seems to be a non-trivial subgroup made up of individuals who use Facebook in very narrow ways, and are very worried about this service’s attempt to manipulate their time and attention to bolster profit.

To accommodate both these realities, this group deploys aggressive tactics and tools to reshape Facebook into something that provides them exactly what they need, without all the other frustrating noise.

Reshaping Facebook

Members of this group, for example, often remove the Facebook application from their smartphone. Almost no important use of this service requires that you can access it at any time or place: loading the site through a web browser is typically sufficient.

Facebook pushes the mobile application mainly because it allows them to monetize your time attention in places that advertisers previously could not reach — standing in line, bored in a meeting, waiting for the metro. This is great news for Facebook investors, but bad news for those trying to maintain some autonomy over their time and attention.

Members of this group are also quite suspicious of the Facebook news feed — a source of engineered distraction sprinkled with injections of social inadequacy and annoyance.

Some respondents explained to me how they aggressively culled their “friends” down to essentially zero to neuter the feed. A surprising number deploy custom web browser plug-ins that block the feed altogether when they load the Facebook site.

Another common observation I heard from this group is that Facebook recently unbundled its messenger application from the rest of its services — allowing those who use the service mainly for communication to avoid having to see the feed altogether.

I’ve also received multiple notes from entrepreneurs who hired people to do the types of marketing related posts that seem necessary these days, while saving the entrepreneur’s more valuable time and attention from the Facebook vortex.

So what do these people use Facebook for? There seem to be three main reasons: participating in carefully curated Facebook groups, communicating with family and friends who are on Facebook but don’t use other communication tools as much, and marketing.

They reject the notion that any one of these reasons should require them to transform into a dehumanized gadget in the Facebook profit machine.

The Facebook Phreaks

I’ve taken to calling this group the Facebook phreaks, an homage to the phone freaks (including, famously, Steve Jobs) who used to hack the telephone network to place long distance calls for free. These modern day phreaks are doing something similar to Facebook’s massive network, except instead of avoiding paying a payphone quarter, they’re preserving the value of their time and attention.

I don’t know how widespread this movement is, but it provides me some hope. Just because a small number of companies have temporarily succeeded in monopolizing much of the Internet doesn’t mean we have to acquiesce to their dominance.

The phreaks are pushing back.

(Photo by Joe Piette)

January 31, 2017

From Tools to Tool Uses

Rethinking How We Think About Tools

In thinking about digital tools we naturally draw analogies to the physical world. In this latter context, tools are often engineered for a specific and clear purpose. A 3/4 inch ratchet wrench is used to secure bolts of that size, and so on.

The translation of this single use understanding of tools to the digital world, however, is creating havoc in our digital lives.

Many modern digital tools, especially those in the social media sector, are engineered to offer dozens of different features, and can be used in a wide variety of different ways. We lose significant control over our time and attention when we settle for thinking about these tools only in the binary sense of: “I use it,” or “I don’t use it.”

Consider, for example, a Facebook addict who checks his feed constantly throughout the day (the average American Facebook user spends over 50 minutes per day on the service — typically split into many, many small checks). Now compare him to minimalist Tammy Strobel, who only uses Facebook’s Fan Page feature as it offers an effective channel to share her online content with fans.

Both “use Facebook,” but the impact of this service on their time and attention is vastly different.

With examples like this in mind, I’m increasingly coming to accept that whether or not you use a tool is not the whole story — it also matters how you use a tool. If a particular social media service supports an important value in your life, for example, don’t let this be the excuse that allows the service full hegemony over your time and attention. Instead, think carefully about how exactly you will use this service in such a way that optimally supports those values without hurting other things that matter to you.

Adapting to the digital world is not just about curating your “tools,” but also carefully crafting your “tool use.” Working with this latter concept greatly expands your options for cultivating a good life in a high tech age.

(Photo by Giorgio Montersino)

January 27, 2017

On Value and Digital Minimalism

The Complexities of Simple

The core idea of digital minimalism is to be more intentional about technology in your life. Digital minimalists carefully curate these technologies to best support things they value.

The idea sounds simple when presented at the high-level, but in practice it dissolves into complexities. One such complexity, which I want to explore here, is the notion of “value.”

Revaluing Value

Measuring whether a given digital tool provides “value” to your life can be a fruitless exercise — the term is simply too vague, and applies to too many things, for it to support hard decisions about what can lay claim to your time and attention. (Everything you use probably offers you some value; why else would you use it?)

With this issue in mind, I’ve sometimes found it helpful to introduce more variation into what I mean by “value” when assessing tools. Consider, for example, the following three different types of benefits a digital technology can provide:

Core Value. A technology offers you core value if it significantly impacts a part of your life that you couldn’t do without — a strand of activity twined around your definition of a life well-lived. For example, a soldier deployed overseas using FaceTime to chat with her family is deriving core value from this tool.

Minor Value. A technology offers you minor value if it provides some moderate positive benefits in the moment. For example, browsing a comedian’s Twitter feed for a laugh, or playing a round of Candy Crush for the distraction.

Invented Value. A technology offers you invented value if it solves a problem that you didn’t know existed before the tool came along. A Snapchat user, for example, might note that it’s the most convenient app for keeping friends posted on what you’re up to throughout the day (it doesn’t even require typing!). But this same user, in an age before SnapChat, probably didn’t even know he wanted constant updates from his friends — the app created the behavior that it optimizes.

The rational for injecting nuance into your definitions of value is that it allows you to inject nuance into your strategies for curating your digital life: you can treat tools differently depending on the value they provide.

Here, for example, is a sample curation strategy built around the above categories:

Actively seek out and enthusiastically embrace technologies that provide core value. Be selective about technologies that provide you minor value and place boundaries around how and when you use them. Avoid technologies that can only provide you invented value (you’re life is too important to be a gadget in some random start-up’s growth plan).

The above strategy is not definitive — it’s just an example. But it underscores the larger observation that figuring out which digital technologies brings value to your life is an effort aided by reflection on what exactly you mean by “value.”

(Photo by Dirk Marwede)

January 23, 2017

Top Performer is Open

The Return of Top Performer

Top Performer, a career mastery course developed over the past four years by myself and Scott Young, is open this week for new registrations.

Top Performer is an eight-week online course that is designed to help you develop a deep understanding of how your career works, and then apply the principles of deliberate practice to efficiently master the skills you identify as mattering most.

We’ve had over two thousand students go though this course to date, representing a wide variety of different professions, backgrounds, and career stages.

Registration for new students will be up until Friday at midnight Pacific Time. After this we will close the registration page so we can prepare for the new session to start.

If you’re interested in joining the new session, or just want to find out more about the course (including multiple case studies and detailed FAQs), please check out the course registration page before Friday.

#####

Addendum: Scott and I try to open new sessions once or twice a year, but the frequency can depend on many factors. If you’re thinking of skipping this session to join the next, the wait might be long. Keep in mind that once you sign up you gain lifelong access to the course and all future updates and sessions. And even though we start each new session at a given time, there’s no obligation to progress through the session at a set pace. You can start when you’re ready.

January 16, 2017

Are You Working In Your Career or On Your Career?

As you may know, over the past four years Scott Young and I developed an online course about career mastery called Top Performer. It teaches you how to apply the rules of deliberate practice and depth to systematically get ahead in your professional life. We’re planning on opening the course to new students next week. In anticipation for this next launch, Scott and I wanted to share a series of articles on interesting lessons we’ve learned about career mastery from the previous sessions of the course.

Below is the first such lesson. It was written by Scott. To avoid cluttering the blog, the subsequent lessons, and information about when/how to sign up for Top Performer next week, will be sent only to our email lists. If you’re interested, sign up for my email list in the box in the righthand column of my blog.

Take it away Scott…

A Common Complaint

One of the most common complaints Cal and I heard when working on Top Performer is that people feel stuck in their careers. They’re working hard, but they don’t know why they’re not getting ahead.

Sound familiar?

It turns out a big reason people get stuck has to do with a small distinction people rarely make when pursuing professional advancement: the difference between knowledge and meta-knowledge.

Meta-Knowledge

Doing well in your career requires two crucial factors: first, you need to be able to do your work well. This requires knowledge. If you’re a programmer, you need to master the languages you work with. If you’re an entrepreneur, you need to know your market and how to serve them. If you’re a lawyer, you need to have a rich knowledge of the law.

However, this is only the first factor. The second is meta-knowledge.

Meta-knowledge is knowledge about how your career works. For example, which skills matter, and which you should ignore, and how best demonstrate your talent in your particular industry, and so on.

This second factor is often invisible and many people can go their entire careers without getting a very good picture of how people succeed beyond their current station.

One of Cal and my students from Top Performer, Chris L., didn’t even realize that he was missing it, telling us: “I was frustrated specifically because I thought I was doing a good job, and I see people who I don’t think are doing a good job and they’re getting ahead of me. I work hard, but nothing happens.”

He had knowledge but didn’t realize he was missing meta-knowledge.

How Do You Get Meta-Knowledge?

Figuring out how your field really works isn’t easy, but it can make a huge difference. Instead of guessing, you can know with confidence which skills are worth investing in and which are not. You can know which positions are stepping stones and which are dead-ends.

The main route to meta-knowledge is good, old fashioned research. This kind of research rarely comes from school or books, it instead comes from other people.

Talking to people who are ahead of you in your career and comparing them to people who aren’t is often a very successful strategy to isolate which skills and assets you need to develop. Ask yourself: what is the successful group doing different than the comparable group that is falling short? The answer is often different than you might at first guess.

An important, but counter-intuitive, strategy we found essential in this style of research is to avoid simply asking people for advice. When you ask for advice, you’ll often get vague, unhelpful answers. Instead, you need to observe what the top performers in your field are actually doing differently. Act like a journalist not a protege. This can often yield surprising insights about what actually matters to move forward.

In Top Performer, Cal and I worked hard to develop a system of doing research geared towards accomplishing exactly this goal — extracting useful meta-knowledge about what matters in your career and avoiding the usual fluff and platitudes like “work hard” or “have good communication skills.”

Put another way, treat this information gathering step with respect: it’s non-trivial to get right.

(For an example of this type of meta-knowledge acquisition in action, see Cal’s post about his systematic efforts to understand what really matters for obtaining academic tenure at a research university.)

(Photo of and by Rachel Maddow)

January 10, 2017

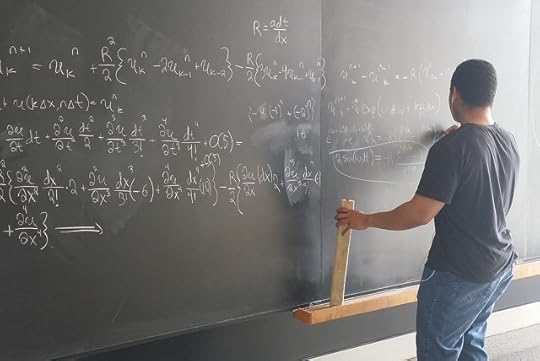

Stephen Hawking’s Productive Laziness

Hawking’s Fixed Schedule Productivity

In the 1980s, at the height of his intellectual productivity, Stephen Hawking used to head home from his office between five and six. He rarely worked later.

Here’s how he explained his behavior to his PhD student Bruce Allen (now a professor at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics):

“Bruce, here’s some advice: The problem with physics is that most of the days we don’t make any major headway (on our projects). That’s why you should do other stuff: listen to music, meet good friends. There’s one exception to this rule: If you find a solution for a given problem, you work 24 hours a day and forget everything else. Until the problem is solved in its entirety.”

I’ve seen this behavior before from other elite level creatives. For them, deep, audacious results are the only currency that matters. The idea of being busy for the sake of being busy in between those big swings seems superfluous.

To be sure, they constantly seek inspiration in reading and daydreams and conversation with other elite producers, but this is a pleasurable background hum that precedes the cacophony instigated by the eventual epiphany.

(For a great study in the reality of “24 hours a day and forget everything else” technical work at the highest level, I recommend Birth of a Theorem.)

Most of us are not Stephen Hawking and never will be. I wonder, however, if there’s not a more general lesson lurking for anyone who wants to produce valuable things: go big when the work demands it, but outside those situations leave plenty of time for music and good friends.

(Photo by Bryan Alexander. The above quote was translated to English from a German newspaper article. Hat tip: David.)

January 5, 2017

On Rooted Productivity

The Root Of All Productivity

The new year is here, which means productivity tweaks are in the air.

I’m not going to offer you a specific strategy today. Instead, I want to touch briefly on a meta habit that will help you succeed in any number of areas in your life where you seek more effectiveness.

It’s something I’ve used for years but have never discussed publicly before. I call it: rooted productivity.

Before describing this idea let me motivate it.

A little discussed issue in the productivity community is the role that these strategies play in your mental life. Most people maintain a haphazard and shifting collection of rules and systems only in their head. When a blog post inspires them, this collection may grow, while approaches they once embraced might fizzle unexpectedly.

This unstructured approach to organizing the ideas that are supposed to organize your life can cause problems, such as…

Open loop syndrome. As David Allen taught us, having commitments maintained only in your head requires constant mental resources and can generate stress or anxiety. A commitment to a specific productivity habit kept only in your head can be just as taxing as any other type of open loop.

Fragile motivation. A commitment to a productivity habit casually kept only your head occupies a low status in your hierarchy of important things in your life. A lot of people get excited about a hack when they first read about it, but it’s all too easy for it to fade away along with their initial enthusiasm.

Evaluation entanglement. Keeping your productivity commitments all tangled in your head can cause problems when a strategy fails. Without more structure to the productivity portion of you life, it’s too easy for your brain to associate that single failure with a failure of your commitments as a whole, generating a systemic reduction in motivation.

The solution to these issues is simple: maintain a single root commitment, that you’ll stick to no matter what, which will in turn help you get the most out of all the other productivity commitments that come and go in your life.

To be more concrete, create a single page document that describes the key productivity rules, habits, and systems (which I’ll summarize as “processes” in the following) that you currently follow in your life.

I type mine and keep it near my desk in a plastic sleeve (for privacy reasons, I’m showing you only the back below):

Some of the commitments on my root document include: daily and weekly planning, GTD task capture, my deep work rituals, my exercise routines, and the systems I use to track and review ideas.

Once you’ve written this root document you must make the following unbreakable root commitment:

I will do my best to: (a) follow the processes on these document; and (b) on a regular basis evaluate these processes and update the document to better reflect what’s working and what’s not, as well as what’s important to me and what’s not.

This philosophy is simple to implement, but in a single stroke it eliminates most of the major problems of a more ad hoc approach to personal productivity; e.g.,

you minimize open loops, as all you have to remember is to try to do what the root document says;

you strengthen your motivation, as the processes you’re supposed to be following are printed in black and white as oppose to just wallowing in the churn of your cognitive landscape; and

it’s easy to modify or discard specific productivity processes without negatively impacting others, as these evaluations and updates are part of your core commitment.

My suggestion for the new year, in other words, is that before you make any new commitments to improve your life, start with this one root commitment that can serve all the rest.

(The above image shows Study Hacks HQ — e.g., my home office — ready for a new year of productive deep work…)

December 20, 2016

Some Thoughts on Transitioning to Digital Minimalism

A Minimalist Transition

Earlier this week, I posted some thoughts on digital minimalism: the idea that using less technology, but using what you do use better, is the key to cultivating meaning in a noisy world.

I want to pull on this thread some more. One question that seems particularly relevant is the process of shifting into this lifestyle.

It seems to me that there are two major approaches that might work: subtractive and additive…

The subtractive approach could also be called the Marie Kondo strategy. You survey each digital tool you regularly use one by one, and ask for each:

Is this significantly supporting a principle I believe to be key to living a good life?

If the answer is “no,” then take a break from that tool. If the answer is “yes,” keep it in your life.

The additive approach, by contrast, is slightly more aggressive but probably more effective. Start by eliminating all optional digital tools from your life for a short period. Thirty days is a good length, but the specifics aren’t crucial.

During this period of digital seclusion, consider the principles you consider key for living a good life, and for each ask:

What use of digital tools might best help me act on this principle in my life?

Once you’ve considered each principle, you’ll be left with a small but well-motivated set of digital tools that each plays a significant role in your life.

A Minimalist Caveat

In both transition approaches mentioned above, there’s a caveat (mentioned in my last post) that I think is crucial: it’s important to distinguish the best from the rest. Don’t settle for a tool that just plausibly supports an important principle in your life, think creatively about what tools (and accompanying behaviors) would best support that principle.

Case Study: Supporting a Desire to Stay Informed About Politics

Let’s explore a case study to illustrate this caveat. Assume that civic life is important to you and accordingly you want to maintain a sophisticated understanding of the various ideas undergirding American politics at the moment.

Obsessively checking a Twitter feed that follows numerous politicos would be better than nothing. But is this the best way to serve this principle? Probably not.

The Internet gives you access to essentially every newspaper and magazine in the country. Most of these publications offer a weekly or daily briefing that sends a digest of the most important stories to your email inbox.

You could subscribe to these email newsletters for a representative set of newspapers and magazines both in the mainstream and sampled from the left and right of the political spectrum, and then have them filter into a special folder in your inbox.

You could then indulge in a weekend ritual where you bring a tablet to a coffee shop and begin sifting through these digests, diving deeper into the articles when the headline catches your attention. You could even do this sifting at home, then print the most attention-catching articles and bring the physical copies somewhere quiet to read.

This latter approach requires more effort than downloading the Twitter application and tapping when bored, but imagine the impact if you were regularly diving into the political thinking of the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Mother Jones each week — noticing the fundamental disagreements; building familiarity with the major streams of contemporary ideological thinking, etc.

Conclusion

The two approaches described above for shifting toward minimalism are tentative, and my case study is at best a sketchy thought experiment, but I think they capture something fundamental about digital minimalism: new technologies can massively improve important areas of your life, but you really have to work at it if you want to fully enjoy those benefits.

(Photo by gordonplant)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers