Cal Newport's Blog, page 37

December 17, 2016

On Digital Minimalism

The Curmudgeonly Optimist

People are sometimes confused about my personal relationship with digital communication technologies.

On the one hand, I’m a computer scientist who studies and improves these tools. As you might therefore expect, I’m incredibly optimistic about the role of computing and networks in our future.

On the other hand, as a writer I’m often pointing out my dissatisfaction with certain developments of the Internet Era. I’m critical, for example, of our culture’s increasingly Orwellian allegiance to social media and am indifferent to my smartphone.

Recently, I’ve been trying to clarify the underlying philosophy that informs how I think about the role of these technologies in our personal lives (their role in the world of work is a distinct issue that I ‘ve already written quite a bit about). My thinking in this direction is still early, but I decided it might be a useful exercise to share some tentative thoughts, many of which seem to be orbiting a concept that I’ve taken to calling digital minimalism.

The Minimalism Movement

To understand what I mean by digital minimalism it’s important to first understand the existing community from which it takes its name.

The modern minimalism movement is led by a loose collection of bloggers, podcasters, and writers who advocate a simpler life in which you focus on a small number of things that return the most meaning and value — often at the expense of many activities and items we’re told we’re supposed to crave.

Minimalists tend to spend much less money and own many fewer things than their peers. They also tend to be much more intentional and often quite radical in shaping their lives around things that matter to them.

Here’s how my friends Joshua and Ryan (aka, The Minimalists) describe the movement:

Minimalism is a lifestyle that helps people question what things add value to their lives. By clearing the clutter from life’s path, we can all make room for the most important aspects of life: health, relationships, passion, growth, and contribution.

(For some excellent examples of minimalism blogs, I recommend: The Minimalists, Leo Babauta, Joshua Becker, Tammy Strobel, the Frugalwoods and Mr. Money Moustache. See also Joshua and Ryan’s sharp documentary on the topic now streaming on Netflix.)

These ideas, of course, are not new. The minimalism movement can be directly connected to similar ideals in many other periods, from the voluntary simplicity trend of the 1970s to Thoreau. But what is new is their embrace of tools like blogs that help them reach vast audiences.

I first encountered this movement through Leo Babuta’s Zen Habits blog about a decade ago. This was the early days of Study Hacks and these sources soon played a major role in transforming my writing and speaking during this period. Most notably, they shifted my attention away from the technical aspects of studying and toward the philosophical aspects of creating a meaningful student experience (the Zen Valedictorian, for example, owes an obvious debt to Zen Habits).

It occurred to me recently, when I was pondering my philosophy on technology, that my thinking continues to be influenced by minimalism. I am, I realized, perhaps usefully described as an advocate for a new but urgently relevant branch of this philosophy — a branch focused on the proper role of digital communication technologies in our increasingly noisy lives…

Digital Minimalism

Adapting some of the above language from Joshua and Ryan, I loosely define digital minimalism as follows:

Digital minimalism is a philosophy that helps you question what digital communication tools (and behaviors surrounding these tools) add the most value to your life. It is motivated by the belief that intentionally and aggressively clearing away low-value digital noise, and optimizing your use of the tools that really matter, can significantly improve your life.

To be a digital minimalist, in other words, means you accept the idea that new communication technologies have the potential to massively improve your life, but also recognize that realizing this potential is hard work.

Here’s a preliminary list of some core principles of digital minimalism…

Missing out is not negative. Many digital maximalists, who spend their days immersed in a dreary slog of apps and clicks, justify their behavior by listing all of the potential benefits they would miss if they began culling services from their life. I don’t buy this argument. There’s an infinite selection of activities in the world that might bring some value. If you insist on labeling every activity avoided as value lost, then no matter how frantically you fill your time, it’s unavoidable that the final tally of your daily experience will be infinitely negative. It’s more sensical to instead measure the value gained by the activities you do embrace and then attempt to maximize this positive value.

Less can be more. A natural consequence of the preceding principle is that you should avoid wasting your limited time and attention on low-value online activities, and instead focus on the much smaller number of activities that return the most value for your life. This is a basic 80/20 analysis: doing less, but focusing on higher quality, can generate more total value.

Start from first principles. Digital maximalists tend to accept any online activity that conceivably offers some value. As most such activities can offer you something (few people would write an app or launch a web site with no obvious purpose) this filter is essentially meaningless. A more productive approach is to start by identifying the principles that you as a human find most important — the foundation on which you hope to build a good life. Once identified, you can use these principles as a more effective filter by asking the following question of a given activity: will this add significant value to something I find to be significantly important to my life?

The best is different than the rest. Assume a given online activity generates a positive response to the question from the preceding principle. This is not enough. You should then follow up by asking: is this activity “the best” way to add value to this area of my life? For a given core principle, there may be many activities that can offer some relevant value, but you should focus on finding the small number of activities that offer the most such value. The difference between the “best” and “good enough” in this context can be significant. For example, someone recently told me that she uses Twitter because she values being exposed to diverse news sources (she cited, in particular, how major newspapers were ignoring aspects of the Dakota pipeline protests). I don’t doubt that Twitter can help support this important principle of being informed, but is a Twitter feed really the best use of all the Internet has to offer to achieve this goal?

Digital clutter is stressful. The traditional minimalists correctly noted that living among lots of physical clutter is stressful. The same is true of your online life. Incessant clicking and scrolling generates a background hum of anxiety. Drastically reducing the number of thing you do in your digital life can by itself have a significant calming impact. This value should not be underestimated.

Attention is scarce and fragile. You have a finite amount of attention to expend each day. If aimed carefully, your attention can bring you great meaning and satisfaction. At the same time, however, hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested into companies whose sole purpose is to hijack as much of your attention as possible and push it toward targets optimized to create value for a small number of people in Northern California. This is scary and demands diligence on your part. As I’ve written before, this is my main concern with large attention economy conglomerates like Twitter and Facebook: it’s not that they’re worthless, but instead it’s the fact that they’re engineered to be as addictive as possible.

Many of the best uses of the online world support better living offline. We’re not evolved for digital life, which is why binges of online activities often leave us in a confused state of strung out exhaustion. This explains why many of the highest return online activities are those that take advantage of the Internet to improve important aspects of your offline life. Digital networks, for example, can help you find or form a community that resonates with you, but the real value often comes when you put down your phone and go out and engage with this new community IRL.

Be wary of tools that solve a problem that didn’t exist before the tool. GPS helped solve a problem that existed for a long time before it came along (how do I get where I want to go?), so did Google (how do I find this piece of information I need?). Snapchat, by contrast, did not. Be wary of tools in this latter category as they tend to exist mainly to create addictive new behaviors that support ad sales.

Activity trumps passivity. Humans, deep down, are craftsmen. We find great satisfaction in creating something valuable that didn’t exist before. Some of the most fulfilling online activities, therefore, are those that involve you creating things, as oppose to simply consuming. I’m yet to meet someone who feels exhilarated after an evening of trawling clickbait, yet I know many who do feel that way after committing a key module to an open source repository.

The above list, and much of the thinking behind it, is still tentative. I should also emphasize again that it applies almost exclusively to the role of digital technology in your personal life, and is largely distinct from my thinking about how to integrate technologies productively in the professional sphere.

But there’s something coherent lurking in the background here that I will continue to work through.

Digital minimalism, for example, has helped me better understand some of the decisions I’ve made in my own online life (such as my embrace of blogging and rejection of major social media platforms), while at the same time challenging me with areas where I could be leveraging new technologies to even better support some of my core principles. In other words, like any productive philosophy, it gives me both clarity and homework.

The bottom line of this general thinking is that a simple, carefully curated, minimalist digital life is not a rejection of technology or a reactionary act of skepticism; it is, by contrast, an embrace of the immense value these new tools can offer…if we’re willing to do the hard work of figuring out how to best leverage them on behalf of the things we truly care about.

(Photo by Loren Kerns)

December 6, 2016

From Deep Tallies to Deep Schedules: A Recent Change To My Deep Work Habits

The Tally Problem

When I was writing Deep Work I was a heavy user of deep work tallies: a record kept each week of the total hours spent in a state of unbroken concentration (see above).

This strategy provides concrete data about how much deep work you actually accomplish, and the embarrassment of a small tally motivates a more intense commitment to finding time to focus.

I’ve written about this idea on this blog (e.g., here and here) and featured it in the conclusion of Deep Work, and for good reason: it works well — especially as compared to no tracking at all.

Over the past year or so since publishing my book, however, I’ve found myself drifting from this particular productivity tool.

I increasingly found it insufficient to support the long periods of deep work (think: 4 – 7 consecutive hours, multiple times a week) that I need to really support my increasingly complicated pursuits as a professional theoretician with heady aspirations.

The problem was timing.

By the time the average week started, I had already agreed to enough meetings, interviews, appointments and calls in advance that no such long unbroken periods remained. This was true even after I drastically reduced these incoming requests with sender filters and my attention charter.

As I found myself repeatedly frustrated with the fragmented nature of my weeks I knew something had to change…

Deep Scheduling

In response to these issues I began to drift toward a new and even more effective strategy: deep scheduling.

The idea is also straightforward. I now schedule my deep work on my calendar four weeks in advance. That is, at any given point, I should have deep work scheduled for roughly the next month.

Once on the calendar, I protect this time like I would a doctor’s appointment or important meeting. If you try to schedule something during a deep work block I’ll insist I’m not available.

This four week lead time is sufficiently long that when someone requests a chunk of my time and attention for a given week, I’ve almost certainly already reserved my deep work blocks for that period. I can, therefore, schedule the request with confidence in any time that remains.

Interestingly, this strategy did not really change my availability. I still end up participating in roughly the same number of these scheduled commitments in a given week as I did back in the tally days, but these commitments now tend to be much more consolidated in my weekly schedule.

The people making the requests can’t tell the difference, but I certainly can!

Deep scheduling, of course, is just one of many always shifting and evolving strategies that support deep work in my schedule. Perhaps the larger point here is not that this one strategy is vital, but instead that it’s vital to keep questioning and tweaking your own productivity habits.

A deep life is indeed a good life, but it requires, as I’ve learned, constant cultivation.

#####

Longtime readers know I’m a big fan of 80,000 hours — a non-profit organization based at Oxford University that offers evidence-based and incredibly effective advice for building a working life that matters (as oppose to, for example, naively chasing “passion”). Anyway, they just published their first book and they are giving it away for free. If you worry about career satisfaction and impact, it’s worth checking out.

November 29, 2016

Your Most Important Thing Is Not Enough

The Other MIT in My Life

One of the most persistent and popular strategies in the online productivity community is the notion of tackling your most important thing (MIT) first thing in the morning.

The motivation is self-evident. Our days are increasingly filled with distraction and unexpected disruptions. If you make a point of doing one important thing before exposing yourself to that onslaught you can ensure that you make continual progress on things that matter .

I’m not sure about where the idea originated. My research suggests it was adapted over a decade ago from Julie Morgenstern’s book Never Check Email in the Morning by Lifehacker editor Gina Trapani. I first heard about MITs through Leo Babauta (a major inspiration) in the early days of Study Hacks, but continue, to this day, to hear people talk about their commitment to the strategy.

Here’s the thing: I don’t want to dismiss this advice, as I know it has helped many people transition from chaos to less chaos. But I do want to urge those who are serious about their effectiveness to look beyond this suggestion.

It’s amateur ball. The pros play a game with more serious rules…

Zero-Based Time Management

My main issue with the MIT strategy is that it implicitly concedes that most of your day is out of your control. You better get that MIT done right away, it tells you, before the wave of messages, pings, posts and drop-bys drag you into a reactive frenzy.

The more effective answer, however, is to reject the premise that your day must unfold reactively.

Someone who plans every minute of their day, and every day of their week, is going to accomplish an order of magnitude more high-value work than someone who identifies only a single daily objective.

To be fair, as many people have pointed out to me, this zero-based time management approach, in which every minute has a job, is annoying: tasks take longer than expected, urgent things drop unexpectedly onto your plate, and so on.

But in my experience, if you integrate enough buffers into your daily schedule, and are comfortable refactoring your plan as needed, you’ll find that your professional life is perhaps not quite as unpredictable as you assumed.

More importantly, you’ll also likely discover that a proactive schedule that requires multiple on-the-fly adjustments is still significantly more productive than the MIT approach of tackling one pre-planned task then relinquishing the reins to whomever happens to be filling your inboxes at the moment.

In other words, don’t settle for a workday in which only an hour or two is in your control. Fight for every last minute. Even if you don’t always win, you’ll end up better off.

#####

For more on my zero-based time budget approach see Rule #4 of Deep Work and these past posts:

The Importance of Planning Every Minute of Your Day

Three Recent Daily Plans

Plan Your Week in Advance

Spend More Time Managing Your Time

(Photo by Andreas Nilsson)

November 23, 2016

What I’m Talking About When I Talk About Social Media

My Curmudgeonly Musings Go National

On Sunday, I published an op-ed in the New York Times arguing that social media can cause more harm than good for your career.

The core of my argument is that the professional benefits of social media are being overemphasized (I don’t buy this idea that suddenly Twitter and Facebook are the main channels through which talent is recognized and opportunities spread), while the professional costs of social media are being underemphasized (see: Deep Work).

As indicated in the above screenshot, this generated some discussion.

Of the different reactions that made it onto my radar, the one I found most interesting was the question of how to define “social media” in the context of these types of cost/benefits analyses. (See, for example, the thoughtful self-analysis in this Hacker News thread.)

I think it’s worth me taking the time to clarify my thinking on this issue.

Engineered Addiction

When I’m speaking negatively about “social media,” I’m almost always referring to the major services offered by the major attention economy conglomerates; Twitter, Facebook, etc.

These companies, like any media company, harvest your time and attention and transform it into revenue. This is a lucrative industry, so they invest a large amount of resources into making their services as addictive as possible.

The ideal use case for these companies is that you return persistently to their services throughout most of your waking hours (c.f., Jim Clark talking about a social media panel where a panelist was raving about the growing number of users spending 12+ hours a day on Facebook).

Contrary to some recent strains of thinking, I don’t think these companies are doing anything unethical, much in the same way I wouldn’t condemn a television network for trying to produce the most watchable possible programming.

But a side effect of this addictiveness is that it can cripple your ability to perform deep work, which, as you know, I think could have disastrous consequences for both your professional success and personal fulfillment.

This definition of “social media” is quite narrow. It doesn’t include, for example, individual blogs, or discussion forums, or homegrown sites like Hacker News — as these services haven’t been massively optimized to colonize our cognitive landscape.

I know many people who are dismayed about how much time they spend checking Facebook, but (to my secret disappointment) I’ve never met someone whose claimed the same about Study Hacks.

In other words: I like the Internet and I like its potential to connect, energize, and inform people (while also recognizing, of course, its scary potential to misinform and divide on a mass scale). But I’m wary of the small number of services that have conquered our culture by claiming to be synonymous with these goals while in reality plotting to squeeze every last cent of value out of our scarce attention.

(For an interesting take on this general topic, see Douglas Rushkoff’s excellent Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, which argues that homegrown, peer-to-peer style services are the key to the Internet living up to its full potential.)

November 15, 2016

The Impact Formula: New Evidence on the Factors that Lead to Breakthroughs

Quantifying Impact

Earlier this month, a group of researchers from Albert-Laszlo Barabasi’s circle of network scientists published an important paper in the journal Science. Its nondescript title, “Quantifying the evolution of individual scientific impact,” obfuscates its exciting content: a massive big-data study that dissects the publication careers of over 2800 physicists to determine the combination of factors that best predicts their probability of publishing high impact papers.

As you might expect, this endeavor caught my attention.

A high-level summary of the researchers’ results highlights two major findings:

The first is that “productivity” matters. The more results a physicist produced during a given period the more likely he or she was to stumble onto a high impact result. A common assumption in highly technical fields like physics is that only young people can make breakthroughs. While this research indicated that younger researchers are more likely to produce high impact papers, this was only because they tended to be in stages of their career where they can produce more total results. If you control for productivity, the role of age disappears. In other words, the force stopping a middle-aged theoretician from producing breakthroughs is less deteriorating neurons than it is strengthening university service demands.

The second major finding is that “skill” also matters. The researchers identified a hard to pin down quantity, that they identified with the variable Q, as also playing a key role. If your Q level is sufficient and you are productive, you are likely to produce a high impact paper. If your Q level is high and you are not productive, or if you have a low Q level but still maintain high productivity, you are less likely to generate impact. The key element of Q is that is seems to remain constant throughout a scientist’s career. It’s possible, therefore, that Q captures some fixed natural intelligence that is hard to budge. It is also possible that it captures a lot of the positive impacts of elite level training early in your career.

There are a lot of interesting implications from this work.

For one thing, it hints that individuals in creative fields should bias toward completing and finishing as many skill-based projects as possible. Put simply: productivity yields impact. (One of my first widely read guest posts as a blogger made this exact point that top performers seem to obsess about finishing things.)

Another interesting implication is that the often criticized publish or perish culture in R1 academia might actually have a strong base in evidence: the more academics publish, the more likely they are to produce something impactful.

Of course, this is just a single study so we shouldn’t extrapolate with too much confidence. Its underlying theme, however, is one that seems to come up often (c.f., here and here and here): if you want to produce things that matter, aggressively hone your skill, then apply it to generate as much output as possible.

(Hat tip: Suzyn and the NYT)

November 10, 2016

Neil Gaiman’s Advice to Writers: Get Bored

Boring Advice

Earlier this summer, the beloved writer Neil Gaiman was a guest on Late Night with Seth Meyers to promote The View from the Cheap Seats.

At one point in the interview, Meyers asked Gaiman about boredom. Here was Gaiman’s response:

“I think it’s about where ideas come from, they come from day dreaming, from drifting, that moment when you’re just sitting there…”

“The trouble with these days is that it’s really hard to get bored. I have 2.4 million people on Twitter who will entertain me at any moment…it’s really hard to get bored.”

What’s the solution? Gaiman adds:

“I’m much better at putting my phone away, going for boring walks, actually trying to find the space to get bored in. That’s what I’ve started saying to people who say ‘I want to be a writer,” I say ‘great, get bored.'”

Given that I have a chapter in my latest book titled Embrace Boredom, I was pleased to hear Gaiman’s advice.

I have definitely found it to be true in the creative pursuits that dominate my professional life. If I want to crack a proof or polish an important idea there’s really no substitute for hours and hours of just thinking.

The relationship is so linear that it’s almost (to reuse the word) boring. The more time I spend just walking and cogitating and being bored in a given season, the more I produce.

#####

A quick administrative note, Deep Work was nominated as one of the best non-fiction books of the year by the Goodreads Choice Awards. The winners will be selected by reader vote. If you’re a Goodreads member and like Deep Work, consider stopping by the nomination page to cast your vote for depth!

November 7, 2016

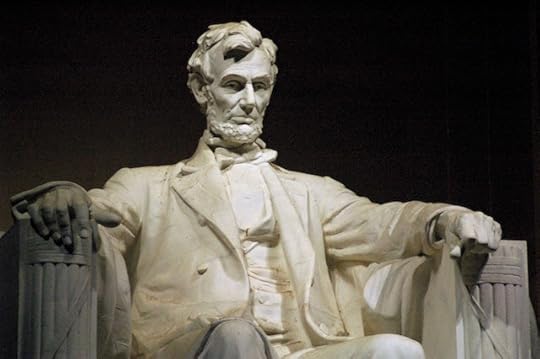

Abraham Lincoln’s Advice to Voters Unhappy with this Election: Suck it Up.

The Lesser of Two Evils

In the early fall of 1848, a little-known congressman from the frontier of Illinois set off to Massachusetts to address fellow members of his political party, the Whigs.

His name was Abraham Lincoln.

To put Lincoln’s trip in context, it’s important to remember that the issue dominating the 1848 presidential election was the expansion of slavery into the new territory won in the Mexican War. The Democratic candidate, Lewis Cass, was in favor of extending slavery to these new territories. The stance of the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor, was less clear, though it was generally assumed he would oppose the expansion.

This assumption was not enough, however, for the strongly anti-expansion Massachusetts Whigs. Taylor was a slaveholder and his refusal to definitively reject expansion made him, in their eyes, a sub-optimal presidential candidate — so they refused to support his nomination, and, during the summer of 1848, became riled up by Charles Sumner, a particularly well-spoken and energized young man who was pushing his fellow party members to vote instead for a dark horse third party candidate, Martin Van Buren, who was emphatically against slavery.

Here’s Sumner talking to the Whigs in Worcester in June, 1848:

“I hear the old saw that ‘we must take the least of two evils’…for myself, if two evils are presented to me, I will take neither.”

This should sound familiar.

Many voters in our current election, on both the left and the right, are attracted to Sumner’s argument. Spurned Bernie Sanders supporters, for example, are looking to Stein as a way to protest attempts to push them into “settling” for the less inspiring Clinton, while disgusted Republicans, uneasy with Trump’s pliable relationship with truth and proto-fascist tendencies, are proudly declaring their intent to write-in a more favored candidate on the ballot.

Sumner would have applauded this commitment to one’s “duty” to do the right thing no matter what.

But not Abraham Lincoln.

He was sent to Massachusetts to push back against Sumner. As William Lee Miller summarizes in his exceptional book, Lincoln’s Virtues, the young Illinois congressmen came to preach an “ethic of consequences.”

Absent of divine revelation, Lincoln argued to the Massachusetts Whigs, the only responsible way to determine your “duty” as a voter is to leverage your “most intelligent judgment of the consequences.”

With respect to the 1848 election, Lincoln argued that votes for Van Buren would take away votes from Taylor and help ensure the election of Cass. That is, the ethical consequence of rejecting Sumner’s “two evils” would be to expand slavery — and to Lincoln, this couldn’t possibly be the right ethical decision for anti-slave voters, regardless of their personal feelings about Taylor.

As Miller paraphrases, Lincoln charges that we need to “discover our duty [through careful weighing of consequences], not [assume] duty to be self-defining, [or] to be taken for granted as revealed.”

I think, however, that Lincoln’s message to the Massachusetts Whigs can be condensed to something even more pithy: suck it up and get over yourself.

My reading of Lincoln (filtered through Miller) is that he found it immorally indulgent to use the voting both as a place to vent frustrations, or make a statement of principles, or send a message to your opponents.

While Sumner was consumed with self-righteousness, Lincoln was worried instead about the messy but necessary business of democracy: figuring out the option that gives the institutions of our fragile republic the best possible chance to keep functioning.

As we face an historically important election tomorrow, this message seemed particularly relevant.

#####

I don’t normally post about politics because this is not a blog about politics. Last night, however, I was having a hard time sleeping and was up late re-reading Miller’s book. This was the chapter I opened to. It seemed providential given tomorrow’s election: so I thought it worth a post. Later this week we’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming.

October 18, 2016

The Opposite of the Open Office

The Bionic Office

A couple weeks ago, I wrote about Joel Spolsky’s claim that Facebook’s massive open office is scaring away talent. The comments on the post added many interesting follow ups; e.g., a pointer to a recent podcast episode where a Facebook developer claims the office is rarely more than a third full as people have learned to stay home if they want to produce anything deep.

A critique of open offices, however, inspires a natural follow-up question: what works better?

For one possible answer we can turn once again to Spolsky.

Back in 2003, when Spolsky was still running Fog Creek, they moved offices. Spolsky blogged about his efforts to work with architect Roy Leone to design “the ultimate software development environment.”

He called it the bionic office. Here a picture of a standard programmer’s space from the outside:

Notice it’s closed off. This is not an accident. Here’s the first item in the brief Spolsky gave his architect:

Private offices with doors that close were absolutely required and not open to negotiation.

Also notice that the office is attractive. The outside features translucent acrylic panels that glow with light. The inside is just as nice. Here’s a photo:

Each office has its own window. But in addition, in the wall behind the monitor, is a cut-out that frames the window in the next office. The goal is to allow the programmer’s eyes to gaze into the distance beyond the monitor, reducing strain. It also brings in light from two sides in every office.

This attractiveness is also not an accident. As Spolsky describes his motivation:

The office should be a hang out: a pleasant place to spend time. If you’re meeting your friends for dinner after work you should want to meet at the office.

This commitment to aesthetics is partly about recruiting, but also partly about the idea that environment impacts quality of work produced (c.f., my posts here and here on deep offices).

Bottom Line

I’m not an architect or an expert in office design. But if I was investing a large amount of capital into human brains, I think I would increase this investment by just a little bit more (relatively speaking) to give the brains an environment where they could produce for me the most valuable possible output.

Spolsky was on to something…

#####

(Open office photo by Juozas Kaziukenas)

October 11, 2016

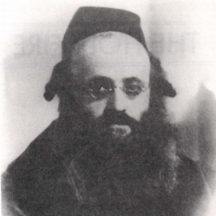

A Famous Rabbi’s Advice for Getting Important Things Done

Kalonymous Kalman Shapira was an influential Polish Rabbi murdered by the Nazis in the Trawniki concentration camp. Before the war, Rabbi Shapira published a respected book on learning titled Chovas haTalmidim, which roughly translates to The Student’s Obligation.

Kalonymous Kalman Shapira was an influential Polish Rabbi murdered by the Nazis in the Trawniki concentration camp. Before the war, Rabbi Shapira published a respected book on learning titled Chovas haTalmidim, which roughly translates to The Student’s Obligation.

A reader (and religious studies graduate student) named Daniel recently pointed my attention to the following excerpt from this book:

“[N]o amount of resolve will help a person unless he learns to budget his time and utilize it for accomplishment. For an undisciplined person’s days and nights are confusion, all of his time is confusion and is wasted. Every night he will say, ‘How did the day pass? I didn’t even feel it passing; it stole away from me and escaped.’ In this fashion, the next day and the following one will also slip away, wasted and used up on inconsequential matters.”

What is Rabbi Shapira’s suggestion to avoid undisciplined time confusion? This should sound familiar…

“If you have compassion on yourself, you will learn to budget your hour; every hour will have its own task. You should decide before you begin how much time you want to spend at even mundane matters…Your hours should not be left open, but should be defined by the tasks you set for them. Write out a daily schedule on a piece of paper and don’t deviate from it; then you will reach old age with all your days intact.”

If this computer science thing doesn’t work out for me, perhaps I should consider yeshiva…

#####

I’m pleased to announce that the audio version of So Good They Can’t Ignore You is now available to listeners in the UK. You can listen to an excerpt here or find our more here.

October 9, 2016

Is Facebook’s Massive Open Office Scaring Away Developers?

In Search of Silence

Joel Spolsky is a well-respected figure in Silicon Valley. He created the popular Trello project manager software and is currently the CEO of Stack Overflow.

He’s also one of the first Silicon Valley insiders to publicly and directly endorse the importance of deep work over the fuzzier values of connection and serendipity.

At the GeekWire Summit earlier this week, Spolsky made the following claim in an on-stage interview:

“Facebook’s campus in Silicon Valley is an 8-acre open room, and Facebook was very pleased with itself for building what it thought was this amazing place for developers…But developers don’t want to overhear conversations. That’s ideal for a trading floor, but developers need to concentrate…Facebook is paying 40-50 percent more than other places, which is usually a sign developers don’t want to work there.”

Spolsky argued that offering private offices and uninterrupted time to concentrate is perhaps one the most valuable benefits you can offer developers in our connected age.

In Deep Work, I noted that most businesses do not yet recognize this activity as a tier one skill, but that this would inevitably shift, and Silicon Valley, with it’s reputation for workplace innovation, would likely be one of the first places we would see the movement begin.

Hopefully Spolsky’s comments are an early indication of my prophetic prowess.

#####

I recently watched a screening copy of Minimalism, a great new documentary by my longtime friends, the minimalists. I was excited to learn that their movie is now the number #1 indie documentary of the year (as measured by box office return). If, like me, you like this type of cultural commentary, you can find the movie online here.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers