Cal Newport's Blog, page 59

April 29, 2012

Do What Works, Not What’s Satisfying: Pseudo-Striving and our Fear of Reality-Based Planning

The Dune Revelation

In July 2009, I took a trip to San Francisco. At some point, I ended up hiking at a sand-duned nature preserve, not far south from Monterey on Highway 1.

What I remember about this hike is a thought that struck not long into the route. In the summer of 2009, I was two months from defending my PhD dissertation. I had arranged for a post doc after graduation but found the academic market beyond to be uncertain for me and my skills. It was in this context that I had my insight:

Why hadn’t I systematically studied the most successful senior grad students when I first arrived at MIT?

Every year, a small number of computer science students at MIT easily generate multiple job offers while the rest have to sweat the process. What do these students do differently from the others? It’s a basic question and yet almost no one arriving in Cambridge seeks an answer. We instead carve out our paths blindly, sticking our heads up only at the end to see if we’ve stumbled anywhere near our destination.

I ended up fine, landing a great tenure track position at Georgetown, but the 2009 version of myself did not have this certainty, and my failure to more systematically plan for my arrival on this market suddenly seemed a glaring omission.

The $100 Startup

This 2009 experience came back to me earlier this week as I read an advance copy of Chris Guillebeau’s new book: The $100 Startup. In this book, Chris tackles a topic made popular by Tim Ferris: how to build a lifestyle business in a digital age.

Lots of people are enamored by the idea of having a business that requires little investment and yet supports you financially while injecting flexibility into your life.

What sets Chris’s book apart, however, is that he was not content inventing a bullet-point system that simply sounds good. He instead systematically studied people who had actually made these types of businesses work. He started with a survey of 1500 such entrepreneurs which he then narrowed down to 100-200 that he interviewed in more detail. He lists them by name in his appendix.

The result is often messier than the internally-consistent, inspiration-boosting acronmyized systems of competing books and blogs, but the advice come across with an authenticity that’s rare for this topic.

Put another way: Chris did with his interest in lifestyle businesses what I should have done as a grad student with my interest in becoming a professor. The only plan he was interested in was a plan grounded in reality.

The Big Question

I’m telling these stories because they inspire an important question: Why do so few people do what Chris did? Most of us are content, it seems, to work hard and build complicated systems, but we avoid basing our efforts on a reality-based assessment of what really matters.

And I think I finally have an explanation…

The Pseudo-Striving Hypothesis

Why do so many ambitious people approach their quest for remarkability in the way I approached grad school, and not in the way Chris Guillebeau approached lifestyle entrepreneurship? Here’s my tentative explanation:

The Pseudo-Striving Hypothesis

It’s significantly more pleasant to pursue a goal with a plan entirely of our own construction, then to use a plan based on a systematic study of what actually works. The former allows us to pseudo-strive, experiencing the fulfillment of busyness and complex planning while avoiding any of the uncomfortable, deliberate, often harsh difficulties that populate plans of the latter type.

For example…

For the aspiring writer, embracing National Novel Writing Month is pseudo-striving. It feels good to sit down every morning and throw a few hundred words on a page. But the reality of writing would tell you that getting your fiction chops to a publishable level requires the training that comes only in the form of writing for someone else — be it an MFA classroom or edited publication. You need the fear of rejection to push your writing skills. Then you still need to experience that rejection time and again during the period where your skills are just starting to improve. It’s much easier to sit on your deck with your MacBook and a cup of coffee and applaud yourself for your dedication.

For the aspiring grad student, seeking research ideas that fall comfortably within the scope of what you already know how to do, and then trying to convince other people that your work is important, is pseudo-striving. Reflecting on my experience, I notice now that academia is much more likely to reward the strategy of spending the 12 – 24 months of deliberate practice necessary to master an important emerging field. This is really hard. But those who persist end up doing work with impact.

For the aspiring lifestyle designer, dedicating hours to e-mail auto-responders, WordPress widgets, and social network engineering is also pseduo-striving. It gives you lots to do, nothing is really judged a success or failure, and nothing is really hard, but you feel engaged and active. It’s quite pleasent. Many of the successful entrepreneurs from Chris’s book, by contrast, had a reality-based fixation on actually making real money from real people before doing anything else (be it leaving their job or optimizing a web site). This is less pleasant, because you might fail time and again to convince people to give you their money, but ultimately it’s all that matters, so that’s where your initial energy should be focused.

Conclusion

When it comes to constructing a remarkable life, I’m increasingly convinced that pseudo-striving is a common trap with devastating consequences. It lulls you into a rhythm of busyness and complexity that might have very little to do with real accomplishment.

I’m not sure why our instincts lead us to flee reality-based planned, but they do. The more explicitly we recognize the difference between pseudo-striving and the messy difficulty of real world accomplishment, the better, I hope, we can refocus our efforts onto what matters.

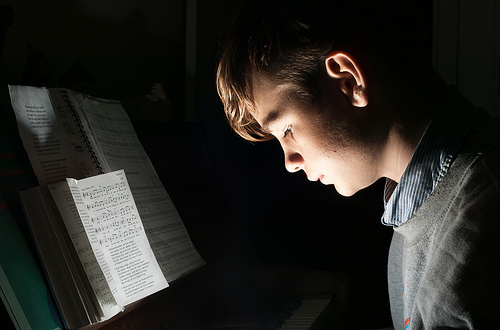

(Photo by rooksbane)

Walking in Merlin Mann’s Footsteps and a Book You Should Know About

Two brief administrative notes…

A2 Earns an A

When I first started blogging in 2007, I needed web hosting. I noticed that Merlin Mann had a note on 43 Folders about his happiness working with a company named A2 Hosting. That was good enough for me: I signed up for their introductory package.

That was five years ago and I’ve been nothing but happy with their service ever since. Now, in a nice bit of circularity, they’ve agreed to sponsor Study Hacks in much the same way they were sponsoring 43 Folders back when I got started with blogging.

So if you’re looking for web hosting, you have my recommendation.

#####

Community College Success

Speaking of recommendations, I have one more to make. An important segment of my readers is community college students. I like these students because they are often way more pragmatic than their counterparts at four year institutions. They see school as an investment and want to get the most out of the money they put in, and therefore they tend to focus more on the nitty-gritty of their strategies (which I enjoy) and less on whether their major is their passion (which I don’t enjoy).

Anyway, a shortcoming of my student writing is that I’ve never done systematic studies of community college students, so my advice in this area is somewhat tentative.

This is why I am happy to enthusiastically recommend Isa Adney’s new book: Community College Success.

If you’re in community college and are looking for advice tailored to your specific setting, Isa’s book is a great place to start.

April 9, 2012

The Father of Deliberate Practice Disowns Flow

Feeling Low on Flow

In a trio of recent articles, I emphasized that flow is dangerous (see here and here and here). It feels good, so we’re tempted to seek it out, but it doesn’t actually help us get better: the key process in creating a remarkable life.

Most of you liked this concept, while a few of you thought I had missed the boat. Here’s an example of the latter sentiment:

I disagree with [your] point. Flow is the experience of being lost in one’s effort. That can easily happen when one is highly challenged and enjoying the intense effort.

There was also quite a bit of discussion on what, exactly, “flow” means, with enough different points of view presented that I soon felt that the whole issue was becoming muddied and difficult to wade through.

Then someone sent me an article penned by Anders Ericsson — the psychologist who innovated the study of how we get better by introducing the idea of deliberate practice. In this article, which was published in 2007 in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science, Ericsson addresses the difference between flow and deliberate practice:

It is clear that skilled individuals can sometimes experience highly enjoyable states (‘‘flow’’ as described by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) during their performance. These states are, however, incompatible with deliberate practice, in which individuals engage in a (typically planned) training activity aimed at reaching a level just beyond the currently attainable level of performance by engaging in full concentration, analysis after feedback, and repetitions with refinement.

In other words, the feeling of flow is different than the feeling of getting better. If all you seek is flow, then you’re not going to get better. There is no avoiding the deliberate strain of real improvement. (This is not the say, however, that you should not seek flow in addition to deliberate practice as a strategy to recharge, or experience it as unavoidable when you put your deliberately honed skills to use.)

Ericsson concludes by echoing a warning familiar to Study Hacks readers:

The commonly held but empirically unsupported notion that some uniquely “talented” individuals can attain superior performance in a given domain without much practice appears to be a destructive myth that could discourage people from investing the necessary efforts to reach expert levels of performance.

He said it. Not me.

#####

This post is part of my series on the deliberate practice hypothesis, which claims that applying the principles of deliberate practice to the world of knowledge work is a key strategy for building a remarkable working life.

Previous posts:

The Satisfying Strain of Learning Hard Material

Beyond Flow

How I Used Deliberate Practice to Ace my Computer Science Final

Flow is the Opiate of the Mediocre: Advice on Getting Better from an Accomplished Piano Player

Is Talent Underrated? Making Sense of a Recent Attack on Practice

Perfectionism as Practice: Steve Jobs and the Art of Getting Good

Complicate the Formula: John McPhee’s Deliberate Practice Strategy

If You’re Busy, You’re Doing Something Wrong: The Surprisingly Relaxed Lives of Elite Achievers

(Photo by Kofoed)

March 28, 2012

The Satisfying Strain of Learning Hard Material: A Deliberate Practice Case Study

A Deliberate Morning

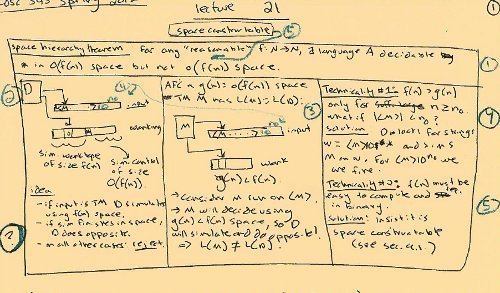

This morning I finished my notes for an upcoming lecture in my graduate-level theory of computation course.

There are two points I wanted to make about these notes…

The process of creating them is very hard. On average, it takes me between 2.5 to 3 hours to prepare a lecture. This preparation requires that I work with absolutely zero distractions as the material is too difficult to be internalized if my attention is divided in any way. Furthermore, the work is not particularly pleasant. Learning things that are this hard does not put you in a flow state. It instead puts you in a state of strain, similar to what is experienced by a musician learning a new technique.

I have gotten better at this process. The lecture I prepared today was the twenty-first such lecture I have prepared this semester. The earliest lectures were a struggle in the sense that my mind rebelled at the strain required and lobbied aggressively for distraction. This morning, by contrast, I was able to slip into this hard work with little friction, tolerate the strain for three consecutive hours, then come out on the other side feeling a sense of satisfaction.

Recently, we have been discussing the deliberate practice hypothesis, which argues that knowledge workers can experience big jumps in value if they apply deliberate practice techniques to their work. My three-month experiment in timed, forced concentration provides a nice case study of this idea. I am now better at mastering hard concepts than I was before. The mental acuity developed from this practice translates over to the research side of my job, helping me more efficiently understand existing results and more deeply explore my own ideas.

To toss the ball back in your court, imagine what would happen if you replaced “graduate-level theory of computation” with a prohibitively complicated but exceptionally valuable topic in your own field, and then tackled it with the same persistence…

#####

This post is part of my series on the deliberate practice hypothesis, which claims that applying the principles of deliberate practice to the world of knowledge work is a key strategy for building a remarkable working life.

Previous posts:

Beyond Flow

How I Used Deliberate Practice to Ace my Computer Science Final

Flow is the Opiate of the Mediocre: Advice on Getting Better from an Accomplished Piano Player

Is Talent Underrated? Making Sense of a Recent Attack on Practice

Perfectionism as Practice: Steve Jobs and the Art of Getting Good

Complicate the Formula: John McPhee’s Deliberate Practice Strategy

If You’re Busy, You’re Doing Something Wrong: The Surprisingly Relaxed Lives of Elite Achievers

March 15, 2012

“Being Very Good at Anything Involves Being Somewhat Addicted”: Hard Truth on the Sheer Difficulty of Making an Impact

The Chess Master and the Economist

A reader recently sent me an interesting interview with Ken Rogoff, a hotshot economics professor at Harvard.

As a young man, Rogoff was a world-class chess player. He eventually translated his ability to grad school where he studied economics with a focus, naturally enough, on game theory. What caught my attention in Rogoff’s interview was his dedication to diligence.

Even two interests, in Rogoff’s thinking, represented one too many:

[A]t graduate school he became convinced that dividing his attention meant that both his chess and his economics were suffering. He had to make a decision. [He chose economics.] “Part of my strategy of moving on was to give it up completely. I don’t play chess casually…Not unless it’s incredibly rude to decline playing.”

He elaborates:

“Being very good at anything involves being somewhat addicted.”

Bottom line: I am increasingly stricken by the yawning gap that exists between the feel-good, follow your passion, be the change you want to see-style chatter that fills the online world, and the reality of how people actually end up making a true impact.

(Image by jojoivika)

March 9, 2012

You’re Working too Hard to Make an Impact

Professorial Exodus

Living in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which I did for many years after college, I learned to recognize a curious ritual. Come June, the academic offices of Harvard and MIT would clear out as a significant fraction of these schools’ professors decamped to New Hampshire, Maine, and, for the more remuneratively famous among them, Martha’s Vineyard.

Some professors I knew would fall off the radar completely, while others would shift to three day a week schedules. But come summer time, you couldn’t take it for granted that a professor would be on campus.

Interestingly, the biggest predictor of a professor leaving was status: the more important a person’s work, the more comfortable they were taking time off. Here’s my hypothesis: once they built confidence in their understanding of value — how to identify what really matters and what it really takes to produce it — they gained the confidence required to push everything else aside.

Are You Busy or Valuable?

When the weather turns nice, as it has been recently down here in DC, I remember this Cambridge ritual. It reminds me of an important point: creating value is unrelated to busyness. When you find yourself — as I sometimes do — working long hours, day after day, reacting and e-mailing and hatching schemes, it’s useful to remember that you’re working more than some of the world’s most respected and impactful thinkers.

The hard part, of course, is that it’s easier to be busy than it is to be valuable — but this shouldn’t stop us from every once and a while taking advantage of a nice day to shut things down and spend a few hours trying to figure out the difference.

(Photo by Christopher Wisker)

February 23, 2012

Don’t Know What To Do With Your Life? Seek Bargains.

A Career Crossroads

In the early winter of 2004, I was a senior at Dartmouth College and in the fortunate position of having two good job offers.

The first was from Microsoft. It paid, by 2004 standards, about as much as you could possibly earn right out of college (around $85,000 in cash and stock per year).

The second offer was to join the computer science PhD program at MIT. It paid considerably less (around $28,000 in stipend) but promised near complete freedom (MIT is quite unstructured and entrepreneurial).

I had no clear preference for which job to take — they both seemed exciting. But in my effort to make a decision, I stumbled on a key tool in the career craftsman toolbox.

Follow a Lifestyle, Not a Passion

In my last post, I argued that the right way to build a remarkable life is to first identify the traits that define your vision of “remarkable,” then pursue only jobs that will reward you with these traits if and when you master rare and valuable skills.

But here’s the snag: what if you don’t know what these traits are?

This is a problem common to students and recent graduates — those who have not yet had enough life experience to figure out what’s possible and what resonates.

This was also my situation as I pondered my competing offers in the fall of 2004. At the time, I was ambitious and optimistic, and had a great sense of potential, but I was also clueless about how best to direct this energy.

This is what I did…

Bargain Shopping Careers

Both jobs, I determined, would reward me well if I built up career capital by mastering rare and valuable skills.

At Microsoft, if you stand out, you gain the ability to acquire some desirable career traits. If you make it to project leader on a hot product, for example, you can have impact, recognition, creativity, and low-level autonomy (i.e., freedom from a direct boss dictating your day to day).

In an academic track, however, I determined that mastering rare and valuable skills would offer an even wider variety of such traits to choose from. If I made a name in the world of research, not only is impact, recognition, and creativity available, but so is a much, much higher degree of autonomy (successful professors are able to craft any number of exotic work setups). It also would allow for the possibility of taking a leave to start a company as well as continuing with my writing (I had just submitted the manuscript for my first book).

I didn’t know which traits I ultimately wanted in my career, but I appreciated that MIT would offer me more options for the career capital I generated. So I turned down Bill Gates and went to work — ironically — in the Bill Gates Tower at MIT.

The Value Rule

The main idea captured by this story is simple:

The Value Rule

When in doubt about which specific desirable traits you want to pursue in your working life, choose the available job option that offers the greatest variety of these traits in exchange for career capital.

Keep in mind, the availability of these traits are irrelevant if you don’t first build up capital by mastering rare and valuable skills — no one gives away such value just because you feel “passionate” about it. But as you advance in this quest to become so good they can’t ignore you, and along the way add sophistication to your value system, it’s likely that you will — as I do now — appreciate the greater flexibility this rule adds to your career crafting process.

(Photo by madelinetosh)

February 18, 2012

Can I Be Happy as an Investment Banker? The Difference Between Pursuing a Lifestyle and Following Your Passion

A Nervous Sophomore

The following question came from a sophomore finance major at a well-known state university:

I have read and heard that entry-level investment bankers have to work long hours doing meaningless grunt work assigned by bosses (sometimes portrayed as evil)…How can your career craftsman philosophy be applied to high stakes fields such as finance?

This reader believed in my career philosophy and was perfectly happy to sidestep the flawed idea that he should “follow his passion.” But the option of heading into investment banking — a popular choice for his major at his university — was making him nervous. The requirements for standing out in this field seemed brutal and he wasn’t inspired by the rewards you can obtain for banking stardom (more respect and money in exchange for more work hours and stress).

I told him not to become an investment banker.

Here’s why…

Lifestyle-Centric Career Planning

The goal of my career philosophy is to craft a remarkable working life. The definition of “remarkable,” however, differs for different people.

One one extreme, it might capture a life of power and respect, where you’re at the center of important matters. While on another, it might capture a life of exotic travel with a minimum of work and a maximum of adventure.

Something most such visions have in common is that they contain traits that are rare and valuable. If you want them, therefore, you need rare and valuable skills to offer in return. This requires that you stop daydreaming about a perfect job that will make you instantly happy, and instead focus on becoming so good they can’t ignore you.

There are a tremendous number of different ways to build up this career capital, which is why I don’t put much emphasis on what specific job you take.

This being said, however, the example from our nervous sophomore above emphasizes an important nuance: not all jobs produce the type of capital you need.

If, for example, your vision involves working four hours a week from a beach, the capital obtained from an investment bank is not the right type of capital for the career traits you seek.

If your vision instead involves impacting major world events, then banking capital can serve you well.

When I talked with our sophomore from above, I learned that his definition of “remarkable” — which emphasized autonomy — was not easily acquirable with banking capital, which is why I advised him to head in a different direction. For other students with other definitions, I might have advised the opposite.

It might seem like “pursuing your definition of a remarkable life” is quite similar to “following your passion,” but for most people, it’s not. A vision for a life well-lived tends to be broad and ambiguous — touching on major distinctions in lifestyle not specific industries or types of work. These are statements of values not commitments to economic sectors.

The following, for example, fit naturally in a definition of a remarkable life:

A desire for time affluence.

A desire for influence and recognition.

A desire for playing a deep, meaningful role in your family and community.

A desire to be known for creativity or to have an impact on the world of ideas.

A desire to be free of financial concerns.

A desire for adventure.

A desire for minimalism (less stuff, less obligations, less mental clutter).

While this list is too specific:

A desire to work in education non-profits.

A desire to be a lawyer.

A desire to be an entrepreneur.

The first list describes general traits of a life well-lived. The second list describes specific strategies for obtaining these traits. My career advice thinks you should be obstinate in protecting the former while not caring much at all about the latter. You need to know where generally you want to go, but you shouldn’t get too obsessed about the uncountably many different routes that can get you there.

###

For more musing on this topic, see my 2008 post on lifestyle-centric career planning.

(Photo by DigiDragon)

February 13, 2012

The Start-Up of You

Many Study Hacks readers are also fans of Ben Casnocha, so it’s probably no surprise to hear that Ben’s new book comes out on Tuesday.

He co-wrote it with Reid Hoffman, one of the founders of LinkedIn. It’s titled:

The Start-Up of You: Adapt to the Future, Invest in Yourself, Transform Your Career

If you’re interested in my Career Craftsman philosophy, you will find a lot of relevant in Ben’s book, where he shows how to apply to your own career the tactics that help Silicon Valley start-ups succeed. (You can read an annotated list of chapters here.)

Highly recommended…

February 5, 2012

Learn the Landscape Before Putting on Blinders: How to Direct Diligence Toward Remarkable Results

The Five Year Eureka Moment

Daniel Kahneman met Amos Tversky in 1969 when Tversky came to Hebrew University to give a talk.

As Kahneman recalls in his 2011 intellectual biography, Thinking, Fast and Slow, the two researchers hit it off and decided to pursue a joint project: figuring out if some people had more of an intuitive grasp of statistics than others.

They discovered that the answer, universally, was a resounding “no.”

“Our expert colleagues…greatly exaggerated the likelihood that the original result of an experiment would be successfully replicated,” Kahneman recalls of their results. “They also gave poor advice to a fictitious graduate student about the number of observations she needed to collect.”

“Even statisticians are not good intuitive statisticians,” he concluded.

This small observation led to a bigger idea: perhaps humans are hardwired with cognitive shortcuts to help them make sense of an uncertain world, and perhaps these shortcuts, in certain situations, consistently lead to irrational conclusions.

This hypothesis was profound. At the time, social science believed that humans were fundamentally rational, and only emotion, like fear or anger, could lead us to irrational behavior. Kahneman and Tversky were proposing that humans, on the contrary, were wired for illogic.

To support this view, they gathered over twenty different examples of cognitive shortcuts consistently leading to irrational conclusions. They combined the results into a paper titled “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.”

They published the paper in the journal Science where it has since become one of the most important studies in all of social science. (According to Google Scholar, it’s been cited over 13,500 times since its publication.) The paper formed the foundation for the field of behavioral economics, which won Kahneman the Nobel Prize in 2002 (Tversky had died seven years earlier).

Here’s what caught my attention about this story. This paper — Kahneman and Tversky’s first publication on their theory — came out in 1974, a half decade after they first began pursuing the underlying ideas. In other words, it took them a full five years to refine a rough hunch, through systematic exploration and discussion, into an idea too good to be ignored.

They were, in short, diligent.

The reason I’m telling you about Kahneman and Tversky, however, is that I’m convinced that there must be more to the story…

The Insufficiency of Diligence

Here’s another story of research diligence.

In 2007, as a third year graduate student at MIT, I was studying the application of distributed algorithm theory to the setting of wireless networks. Around this time, my collaborators and I came up with a model for these algorithms that we thought captured something important about wireless communication.

We ended up publishing the following series of peer-reviewed research papers that explored the mathematical limits of this model:

Gossiping in a Multi-Channel Radio Network: An Oblivious Approach to Coping with Malicious Interference

by Shlomi Dolev, Seth Gilbert, Rachid Guerraoui, and Calvin Newport

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Distributed Computing (DISC). September, 2007.

Secure Communication Over Radio Channels

by Shlomi Dolev, Seth Gilbert, Rachid Guerraoui and Calvin Newport

Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on the Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC). August, 2008.

Interference-Resilient Information Exchange

by Seth Gilbert, Rachid Guerraoui, Darek Kowalski, and Calvin Newport

Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM). April, 2009

The Wireless Synchronization Problem

by Shlomi Dolev, Seth Gilbert, Rachid Guerraoui, Fabian Kuhn and Calvin Newport

Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on the Principles of Distributed Computing (PODC). August, 2009.

Leveraging Channel Diversity to Gain Efficiency and Robustness for Wireless Broadcast

by Shlomi Dolev, Seth Gilbert, Majid Khabbazian and Calvin Newport

Proceedings of the International Symposium on Distributed Computing (DISC). September, 2011.

As I write this, we’re currently preparing a new paper on this topic for publication.

Notice: 2007 to 2012 is five years. This is exactly the time it took Kahneman and Tversky to develop their career-defining mega idea, and yet I’m not holding my breath for a call from Stockholm.

(To be fair, this research direction is solid. These papers were all published in high quality, competitive venues, and combined, they have been cited over 100 times. But they’re not the type of results that make a researcher famous.)

Both my team and Kahneman’s team were equally diligent, but one obtained more remarkable results than the other. My question, then, is simple but important: why the difference?

Directed Diligence

My working answer to my simple question is that there’s a key subtlety in leveraging diligence to achieve remarkable results:

The Directed Diligence Theory

It’s not enough to just focus relentlessly on a small number of things (though this is almost always necessary). You must also direct this diligence by simultaneously and systematically exposing yourself to the reality of what’s valuable in the relevant field.

Kahneman and Tversky’s diligence, for example, was directed by their understanding, as psychology professors, that the model they were pursuing was a radical departure from an orthodoxy that had started to show strain. The field was looking for new models and they knew they were on to one possibility.

In my last post, I offered Steve Martin as another example of diligence breeding remarkability. When you read his memoir, you find a similar direction to his focus. Martin studied comedy like an academic anthropologist, picking apart what was doing well and what was becoming dated. His deep understanding of the evolution of comedy in the 1970s directed his diligence toward real results.

Returning to my own example, it was only a few years ago that I began to internalize this lesson. Just because an idea was interesting to me, I now accepted, was not enough by itself to justify diligent pursuit.

So I made a change to my research method…

Notice in my list above of publications on this topic, there is a two year gap between 2009 and 2011. What happened in these years? I left my theory group to become a postdoc in a systems group that focused on making real world wireless networks better.

This was not an easy transition for a theoretician. I had spent the previous five years working primarily on whiteboards, proving theorems. My first day in the systems group, by contrast, I found that someone had left a toolbox on my desk. A toolbox!

This was a different world.

But here’s the thing: I learned a lot about how real wireless networks work and what the people who build them actually worry about. Since that experience, and my continued extensive interaction with systems researchers, I’ve noticed my diligent work on wireless network theory has begun to drift toward increasingly interesting shores. In a grant application I submitted this past fall, for example, I was able to detail a trio of serious problems from real wireless networks that my style of theory now has the potential of seriously solving.

It might take another five years before I’ll know if this new experiment in directed diligence pans out. But it already feels right.

Conclusion

Remarkable accomplishment requires a remarkable amount of focus; this much is clear. But focus without grounded direction is unlikely to hit the sweet spot.

The key observation, however, is that this directed diligence approach is not about figuring out in advance what you were meant to do or identifying a can’t miss idea. It’s instead about coupling your diligence with continued exposure to what real value looks like. You won’t start out knowing exactly where your story is heading, but you can have confidence that you’ll end up with the right sort of ending.

(Photo by moriza)

#####

This post is part of my series on the diligence hypothesis, which proposes that focusing relentlessly on a small number of things for a large amount of time is a key strategy for crafting a remarkable life. Previous posts on this topic include:

Closing Your Interests Opens More Interesting Opportunities: The Power of Diligence in Creating a Remarkable Life

See also my related series on the deliberate practice hypothesis.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9951 followers