Cal Newport's Blog, page 58

August 7, 2012

The Recorded Life

A snapshot of the mind of Cal…

Personal Hacks

A reader recently noted the following:

It strikes me that you haven’t said much at all on your blog — or for that matter, in your books — about how one ‘succeeds’ at one’s personal life.

It’s true that I tend to keep things professional here at Study Hacks. But this doesn’t mean my personal life escapes similar scrutiny.

Exhibit A is the stack of moleskin notebooks shown at the top of this post.

They’re all full.

I keep one such notebook with me at all times for recording any “important thought” that I might want to revisit later during my monthly check-in. Some of the ideas, of course, relate to my work as a professor or a writer. The page below, for example, which is from September 2, 2010, shows the genesis of my Romantic Scholar series (though, at the time, I was calling it, ill-advisedly, the “aesthetics of student knowledge” series):

At least three-quarters of the notes, however, deal with living a better life outside of work. In other words, I put a lot of thought into hacking the personal — I just tend to be too private to share.

To understand my hesitance, I present Exhibit B:

This page, recorded on May 21, 2009, is one of several entries on the importance of the “500 push-ups project.” Something which I clearly deemed urgent.

Don’t ask…

August 2, 2012

Work Less to Work Better: My Experiments with Shutdown Routines

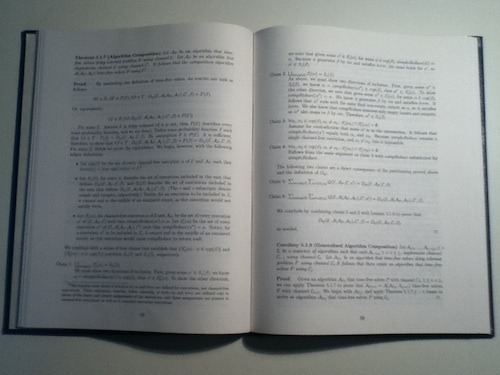

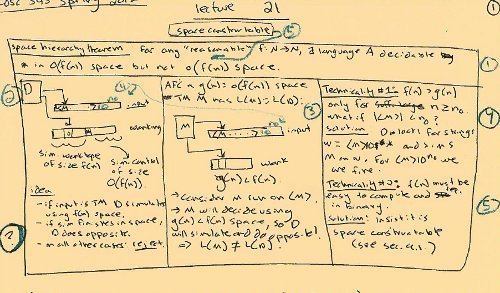

My dissertation. The pages shown here are from a proof that caused significant consternation.

A Novel Dissertation

I began working on my PhD thesis in the summer of 2008. I defended a year later, in early August, 2009.

There’s nothing unusual about this timing. What was unusual, however, was my approach.

By June 2008, I had a fair-sized collection of peer-reviewed publications. The standard practice in computer science would be for me to take the best of these results, combine them, fill in the missing details, add a thorough introduction, and then call the resulting mathematical chimera my dissertation.

To me, naive as I was, this sounded like a waste of a year. So I decided I would prove all new results.

This strategy worked fine for a while, keeping me engaged and happy, but then, in April, 2009, things took a turn toward the difficult. It was during this month that I accepted a postdoc position that would start in September. This meant that I had to defend my thesis over the summer. Suddenly the allure of tackling all new results began to wane.

Here’s a scenario that became common:

I would be working during the day on an important proof.

At some point in the late afternoon I would find a flaw.

A helpful voice in my head would point out that my whole future depended on finding a fix — without a fix, it argued, the thesis would crumble, I would be kicked out of graduate school and end up homeless, likely dying in a soup kitchen knife fight.

After heading home, I would continue, obsessively, seeking a fix — ruining any chance at relaxation that night.

After two weeks of this exercise, I decided something needed to change.

It was then that I innovated my shutdown philosophy…

Schedule Shutdown Complete

In the spring of 2009, I adopted the following ritual to cope with thesis anxiety:

At the end of the work day, I would look over my calendar and tasks. I would then check in on where I stood on my major projects (which, at this point, meant my thesis). After taking in all this information, I would come up with a smart plan for the remainder of the week.

Once I was satisfied with my plan, I would say a quick mantra to officially shut down my scheduling for the day. For me, this was “schedule shut down complete,” which is a phrase with no particular meaning; it just happened to pop to mind the first time I tested the ritual.

The shutdown, however, was not enough by itself. The ruminating part of my mind would still fire up and propose worries about broken proofs and knife fights. This brings me to the second part of the ritual. Whenever I began ruminating on my work schedule after my shutdown, I wouldn’t engage the specifics of the rumination, but instead respond to myself with some variant of the following:

“I completed my schedule shutdown ritual today. I wouldn’t have allowed myself to complete the process if I didn’t trust that my plan makes sense. Therefore, I’m not worried.”

The key point here is that I didn’t try to ignore the urge to ruminate — which rarely works — but I also didn’t engage the specifics of the rumination — which tends to make things worse. My response was logical but also non-specific.

In less than month, the urge to ruminate on these issues had reduced to become essentially non-existent. So long as I did my shutdown each day, my mind had been trained to release work-related anxiety.

The Craftsman in the Cubicle Project

This story came to mind recently because I’m currently in another period of big changes: I’ve had a year now to get used to my new job as a professor, my wife and I bought our first house, and we’re expecting our first child.

The brand new Study Hacks HQ.

The time is right, I’ve decided, for a serious round of self-assessment and improvement.

One target of this scrutiny is my professional life. I write often about my career craftsman philosophy (and in fact even have a whole book coming out on the topic), which emphasizes treating your work as craft: focus intently on developing a small number of valuable skills, then leverage these valuable skills to push your career in a direction meaningful to you.

I want to see how far I can develop this idea in my own life.

Over the next month or two, I’m launching a series of experiments designed to re-focus my working life towards a satisfying, craftsman-like concentration on a small number of powerful skills, and away from open inboxes and continuous low-grade distraction.

I’m pretty good at this already. But I want to discover how much better I can become.

This mission will require logistical changes — e.g., how I structure my day or manage organizational obligations – as well as skill changes — e.g., how I integrate deliberate practice into my work.

I call this the craftsman in the cubicle project because it aims to regain a spirit of craftsmanship in a knowledge work era defined by distraction.

Experiment #1: A Better Shutdown

This brings me back to shutdown routines.

As I move into a new phase of adulthood, a rock solid shutdown ritual is more important than ever before. If I can’t get away from work and recharge effectively with my family, then I won’t be able to consistently achieve the true hard focus needed for a craftsman-style working life. With this in mind, as my first experiment in this project, I’m revisiting my shutdown routine. I want to soup up the graduate student version of this ritual to one that can handle a life with many more serious obligations at work and home.

Here are three specific upgrades I’m trying:

Shifting to Paper

When I introduced this ritual, I would send my daily plan to myself as an e-mail. I knew that my inbox was the one place I would definitely check everyday, preventing my plan from being ignored.The downside of this strategy is that it forces me to check my e-mail in the morning. This often proves disastrous, as logging into Gmail has a way of context-shifting me away from craftsman-like focus, and toward aimless Internet tinkering. In other words, a ritual that was designed to support a craftsman lifestyle is simultaneously subverting this goal.

When I introduced this ritual, I would send my daily plan to myself as an e-mail. I knew that my inbox was the one place I would definitely check everyday, preventing my plan from being ignored.The downside of this strategy is that it forces me to check my e-mail in the morning. This often proves disastrous, as logging into Gmail has a way of context-shifting me away from craftsman-like focus, and toward aimless Internet tinkering. In other words, a ritual that was designed to support a craftsman lifestyle is simultaneously subverting this goal.Fortunately, I’ve been practicing this habit long enough that I’m no longer worried about ignoring my plan. To avoid the distraction of my inbox, therefore, I can confidently shift my daily rundown from an e-mail and into an old-fashioned notebook. Chris Guillebeau recently gave me a nice set of moleskin-style ledgers, one for each month of the year. These should serve perfectly for my purpose (and, as a bonus, after a year, I can easily go back and review my planning process).

Disconnecting my iPod

I don’t have a smartphone, because I like being bored when I’m away from my house (building comfort with boredom, in my weird mathematician world, equates to building one’s ability to focus). I do, however, have an iPod Touch, because I like to download podcasts without having to go through my computer. Some time back, my wife configured my iPod so that I could check my e-mail easily when I’m at home and connected to our network. I hate this temptation because it often wins — ruining my shutdown. Earlier today, as part of my efforts to upgrade my shutdown routine, I deleted my e-mail accounts from the iPod. Checking-in online now requires me to plug in and boot up a computer — something that’s just difficult enough to easily resist.

Committing to a DMZ

In my experience, a shutdown is most successful when you can downshift your mind from the high-energy, tackle all problems state it occupies during the workday, to a more relaxed, present state that works best when at home. This transition can be hard. One method I’ve been toying with is a dedicated meditation zone (DMZ) — which I define as an extended period (at least 20 minutes) of focusing on either a single, non-work related thought, or giving your full attention to a podcast or audio book. The focus on a single thing helps the other parts of your brain shutdown and cool off. As part of my ritual upgrade, I’m committing to a DMZ everyday, immediately following my shutdown. During a normal workday, I’ll use my commute. On a day when I work at home, I’ll use my daily dog walk and exercise. The key will be consistency.

By explicitly eliminating my shutdown ritual’s ability to cause distraction during the workday, and then striving to maintain its integrity after work is done, I’m hoping that it will remain muscular enough to handle this new phase of my life.

I’ll keep you posted. In the meantime, onward to more experiments…

July 24, 2012

Perfectionism is a Loser’s Strategy

Ocean-Front Writing

Yesterday, I submitted an important grant proposal. In a perhaps overzealous interpretation of my adventure studying philosophy, I wrote the bulk of the content on the island of Madeira, in a hotel room overlooking the Atlantic, which turned out to be wonderfully monastic and productive.

The process was hard. I probably spent around 100 hours total; some energized, but most mired in the dreary hinterland of editing. In standard Study Hacks fashion, however, I was organized, and able to spread the work out.

I bring this up because throughout the process I found myself wrestling with insecurity. Every evening, when I was done with my careful plan for the day, the voice of doubt arrived trying to convince me to spend a few more hours editing or to bother a few more people to take a look at my draft. Did I really want a little bit of laziness to be the reason I lost this award?, it would ask.

I was experiencing the classic battle between perfectionism and lifestyle design. This battle is familiar to those who embrace my career craftsman philosophy, because this philosophy requires a balance between becoming “so good they can’t ignore you” and then leveraging this value to build a life you love.

The former goal attracts perfectionism while the latter can’t work if it’s around.

I’m writing this post to share with you the thought process that helps me navigate this mental minefield…

The Source of Value

Whether you’re a professor, writer, student, or entrepreneur, your job is to produce products that are valuable to your audience. The more valuable your product, the more reward you receive.

If my grant “product” is valuable, I get the grant. If a writer’s blog “product” is valuable, she gets an audience. And so on.

At the top of this post, I put a plot that displays my intuitive understanding of product value. Consider, in particular, the column on the left side of the plot, which breaks down the contribution of three different factors as follows:

The vast majority of your product’s value comes from your underlying ability .

The next biggest contributor is providing reasonable packaging for your product. For most audiences, there’s a quality threshold you must cross to be taken seriously. You gain non-trivial value for crossing this threshold. It’s not as important as ability, but it’s important enough that you shouldn’t ignore it.

The final contributor is the time you spend obsessively polishing and worrying and tweaking after you passed the threshold required by your audience. This perfectionism-driven work is by far the least important to the overall value of your product.

View from balcony where I wrote much of my proposal.

For example, for my grant proposal, the most important predictor of my success is my underlying ability as a researcher.

Presenting this vision in reasonable packaging — e.g., a clear, thoughtful proposal — though perhaps less important than the proposed research, is still important enough for me to spend 100 carefully-planned hours working on it.

To continue to obsessively polish after that point, however, would offer diminishing returns at best. Once the reviewers understand my vision and see that I’m serious, it’s the quality of the vision that will dominate the process moving forward.

A Loser’s Strategy

At this point, you might still counter that even if perfectionism adds only a little value, it’s still worth it, as every bit helps in a competitive world.

This inane observation brings me to the right column in the plot at the top of this post. This column reflects my understanding of where stress comes from when creating a product. In particular:

Building your ability is not particularly stressful. It’s something you work on day after day, month after month. It adds up to lots of culumlative deliberate practice, but no particular day is all that bad.

Constructing reasonable packaging can be slightly more stressful as it often requires a lot of work in a relatively short period. But, if you’re a Study Hacks reader, you can tame this process with smart schedules — leaving you enough free time to end your day with a bottle of Coral, watching the sun set over the Atlantic.

Perfectionism, by contrast, can be incredibly stressful. It puts you in a state of constant worry that you’re on the brink of failure. It also tends to push you past your energy reserves and into exhaustion.

This is why I call perfectionism a loser’s strategy: you’re generating a disproportionate amount of stress for a small amount of value. The only reason this strategy makes sense is if you’re convinced that you’re never going to get any better at what you do, leaving this minor polishing at the margins all that’s left in your control.

This is a sad view of life.

Here’s the alternative: focus on getting better. The benefits of improving your underlying skills will dwarf the benefits of perfectionism. If you fall just short of some recognition this year then the next year it will be an easy win and the year after that it will seem trivial. In the long run, in other words, this is the approach that allows exceptional achievement to flourish in a life you love to live — an approach, I can attest from recent experience, that lets you shut down the computer and take a dive into the ocean.

July 13, 2012

On Dominating the World

A Perhaps Ill-Advised Talk

I recently returned from Portland, Oregon, where I was a speaker at Chris Guillebeau’s World Domination Summit. I stood in front of a crowd of 1000 energized, non-comforming, optimistic folks and told them: “follow your passion” is terrible advice.

And I somehow escaped injury.

Actually, the most common response I received: “I completely agree, but other people are going to find your message radical.” After enough people told me they agreed, I concluded something I’ve suspected for a while now: this idea is less radical than we assume.

Perhaps our generation is tired of the passion hypothesis, but just hasn’t gotten used to saying it out loud yet.

All told, I met many interesting people and was exposed to many interesting thoughts. This was not a Study Hacks crowd, but it was a crowd I was honored to join.

If You’re New Here

If you’re a WDS person visiting to find out more about passion and its discontents, I want to point you to my upcoming book, SO GOOD THEY CAN’T IGNORE YOU (pub date: September 18), which lays out my detailed case why “follow your passion” is bad advice, and what you should do instead.

If you’re a WDS person visiting to find out more about passion and its discontents, I want to point you to my upcoming book, SO GOOD THEY CAN’T IGNORE YOU (pub date: September 18), which lays out my detailed case why “follow your passion” is bad advice, and what you should do instead.

Here’s my tentative call to action (I’m such a bad marketer that Chris Brogan, within an hour of meeting me, literally gave me an empty business card holder):

If you love this idea: the single most useful thing you could do for the cause is to pre-order the book (this forces booksellers to take notice).

If you’re on the fence, but want to keep the conversation going: consider clicking that Facebook thumbs-up, likey button on the Amazon page.

If you want to learn more: search my blog for the term “passion” (click here).

Will Return Soon

Anyway, I’m off to Funchal, Madeira tomorrow for a conference of an entirely different tenor (less inspirational speeches, more powerpoint slides full of equations), but I have a series of interesting posts backed up, waiting for my return.

Stay tuned…

(Photo by Chris Guillebeau)

June 29, 2012

On the Remarkably Long Road to the Remarkable

If At First You Don’t Succeed…

Here’s John McPhee reflecting on his path to The New Yorker: ”I had been continually rejected…until I was in my thirties.”

He’s not alone in fostering patience for this particular goal.

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell notes that it took him ten years of training at The Washington Post before he made it to the The New Yorker. Jonah Lehrer had seven years of dues paying between his first book deal, inked as he left his Rhodes Scholarship, and earning his own staff spot.

I like these examples because they remind of a simple truth: remarkable careers take a remarkably large amount of training. If I’m not relentless in my focus, they tell me, I should not count on a life as interesting, autonomous, and respected as that enjoyed by Mr. McPhee.

It’s just enough of a push to turn me away from my latest schemes, and get me back to putting pen on paper and chalk on chalkboard.

June 18, 2012

Impact Algorithms: Strategies Remarkable People Use to Accomplish Remarkable Things

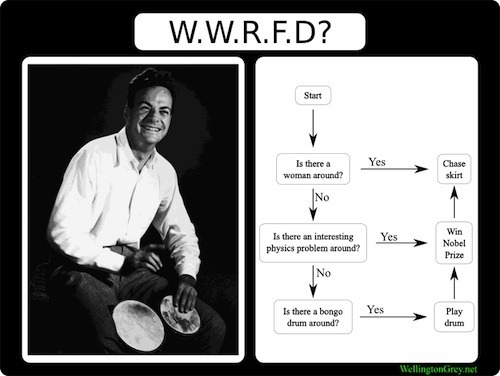

(Image from WellingtonGrey.net via c2.com)

Impact Algorithms

I’ve been writing recently about the impact instinct — the ability to consistently steer your work somewhere remarkable. We know that diligently focusing on a single general direction and then applying deliberate practice to systematically become more skilled, are both crucial for standing out. But true remarkability seems to also require this extra push.

Since writing these posts, readers have sent me an amazing collection of quotes and articles that provide supporting details for this idea. Reviewing these resources, I noticed that the following systematic strategies — let’s call them algorithms — seem to pop up again and again.

Below, I summarize these algorithms, each of which I named for someone remarkable who exemplifies it: I don’t know that they’re all right; I don’t know which work best; but they should provide nuance to our understanding of the impact instinct.

The Feynman Algorithm

Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman is a master of impact. Many people have attempted to understand his curiously successful approach (e.g., this wonderful collection of quotes that a reader sent me). Of the many candidates that might rightfully be called the “Feynman Algorithm,” here’s the one I think played the biggest role in his success:

Simplify the problem down to an “essential puzzle.” Here’s how Danny Hillis explained Feynman’s use of simplicity: “He always started by asking very basic questions like, ‘What is the simplest example?’ or ‘How can you tell if the answer is right?’ He asked questions until he reduced the problem to some essential puzzle that he thought he would be able to solve. Then he would set to work.” (Notice, the importance of simplicity is something we’ve encountered before.)

Continually master new techniques and then apply them to your library of unsolved puzzles to see if they help. As mathematician Gian Carlo-Rota explained when describing Feynman’s use of this strategy: “Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say: ‘How did he do it? He must be a genius!’” (Notice, it’s at this step of the Feynman algorithm that we see the value of ultra-learning.)

The Thrun Algorithm

Computer scientist Sebastian Thrun rocketed to fame when his self-driving car won the Darpa Grand Challenge (though his fame among roboticists long preceded that particular public victory). He now runs Google X, the search company’s skunk works for big impact projects.

Studying Thrun’s story, the following algorithm seems to be at the core of his remarkable accomplishments:

Pick a problem that matters. According to a recent Wall Street Journal profile of Thurn: “His mentor at CMU, Tom Mitchell, told him, ‘Pick a problem that matters to society.’ So he helped create robots, including a “nursebot” to assist the elderly in nursing homes and robotic tour guides…these were hard projects, [Thrun] says. ‘Just let go, trust your ability to learn, more [than] holding on to the things you’ve achieved—and that became the central theme in my life.’”

Stick to it. The problems picked by start researchers who use the Thrun algorithm tend to be surprisingly generic — e.g., create robots that are good for society — but their clarity drives people to learn hard things, make hard connections, and wring the most out of their ability. This sounds obvious, but it really isn’t. The default behavior is, as Thrun warned, to “[hold] on to the things you’ve achieved.” Something needs to push you to keep breaking new ground.

The Erez Algorithm

Study Hacks readers know that Erez Lieberman Aiden, a hotshot young researcher out of Harvard, is my favorite example of the impact instinct. Recently, I’ve heard from several readers who know Erez, his advisors, and/or his academic field. They pointed me toward the following important algorithm that he seems to use to great advantage:

Be Confident. “I knew Erez before he was a grad student,” a reader told me. “And he was extremely confident then. Confidence and boldness pay off enormously in academia.”

If You’re Not Confident, Do Everything You Can to Surround Yourself With People Who Are. This leaves the question of how one becomes confident. In the academic context, the readers who wrote me agreed that this confidence comes from surrounding yourself with people who are already doing remarkable things. “The cultural context here is really, really important,” said one reader. “Eric Lander and Martin Nowak [Erez's mentors] are powerful.” Another reader agreed: “These folks have grown up in groups/labs in which high impact papers are the norm. Not only do you pick up on how high-impact papers are written, but perhaps more importantly you develop the attitude that of course you can make high impact, such papers are something perfectly within your reach because they were routine in your scientific babyhood.”

This Might Mean Getting “Good Grades.” We tend to separate remarkable accomplishments from conformist behaviors like studying hard, as the quest to become remarkable seems inherently rebellious. But a corollary to step 2 from above is that surrounding yourself with confident people often requires that you first jump through well-established hoops. If a freshman tells you that she wants to do research that will change the world, don’t tell her to go find a life changing project — she’s way too early in her development to successful apply the Thurn Algorithm — instead tell her to earn the best possible grades, so she can can make her way into a great graduate school, learn from the best people, and be surrounded by the most confident researchers. This is the foundation that produces remarkable things.

June 12, 2012

What You Know Matters More Than What You Do

Insight into Impact

I recently had an interesting conversation with some colleagues. We were talking about a young researcher in our field who happens to be absurdly productive — typically publishing four or five important results each year. In other words, this is someone with a highly-developed impact instinct.

As you might expect from a group of assistant professors, we were interested in figuring out his secret.

The easy answer is that he’s simply better than most people at solving hard problems. Perhaps where you or I might get stuck, he, in a flash of Good Will Hunting-style brilliance, taps the chalkboard four times and the proof is solved.

Some of my colleagues, however, have collaborated with this star researcher, and could therefore paint a more nuanced picture. He is quite talented, it turns out, but not at what you might expect…

According to my colleagues, this star researcher tends to begin with techniques, not problems. He first masters a technique that seems promising (and when I say “master,” I mean it — he really goes deep in building his understanding). He then uses this new technique to seek out problems that were once hard but now yield easily. He’s restless in this quest, often mastering several new techniques each year.

This sounds like an obvious approach, but it’s not. Most researchers are slow to adopt new bodies of knowledge — mainly because it’s really hard to do.

This star researcher, by contrast, is much more nimble — jumping from technique to technique, finding improvements and making connections.

What’s amazing about him, therefore, is not his ability to solve problems, but his ability to master things that are damn hard, damn quick.

The Ultra-Learning Hypothesis

Here’s something I’ve noticed more and more recently: this ultra-learning strategy is common in people who do remarkable things.

Richard Feynman, for example, used to brag about his ability to learn any topic in a short amount of time, a skill that led to one of modern science’s most breathtakingly diverse and important bodies of work.

Steve Jobs spent his career diving deep into topic after topic in his field — industrial design, operating systems, 3D graphics — so that he could see clearly what was possible.

And so on.

I hypothesize two things. First, ultra-learning is difficult but it can be cultivated. Second, it might be one of the most important skills for consistently generating impact. Those who are able and willing to continually master hard new knowledge and techniques are playing on a different field than those who are wary of anything that can’t be picked up from a blog post. (And yes, I recognize the irony of that statement.)

Both of these hypotheses might prove false. But what’s true is that they’re both deserving of more exploration.

June 3, 2012

Decoding the Impact Instinct

A Tale of Two Applied Mathematicians

Over the past few months, I’ve been working on an interesting research problem. My collaborator and I are taking some math tools typically used to analyze computer algorithms and are applying them to human behavior. Our plan is to publish in a specialized computer science conference. Because the work is different, we assume it might be an uphill battle to gain notice at first.

By itself, this story is not that relevant to our goal of decoding how people build remarkable lives. It gains new importance, however, when we contrast it to the actions of another researcher — someone with a phenomenal talent for remarkablilty, who once faced an eerily similar situation.

Six years ago, Erez Lieberman Aiden, then a 27-year-old Ph.D. student in a joint Harvard-MIT program, had a familiar idea. He also wanted to use the same math tools that interest me to study human behavior. Whereas I’m focused on a modern scenario (how people behave on social networks), Erez studied something more ancient (how cooperation evolved in early humans), but the underlying research strategy was essentially the same.

It’s here, however, that our stories diverge…

I’m targeting my results for a specialized venue and am still uncertain about its reception. Erez, by contrast, was more confident. He quickly wrote up his ideas and published them as a short note in Nature, one of academia’s most influential journals. The note might have been short, but its impact was long-lived: in the half-decade since it’s publication, its been cited over 550 times.

I’ve written in detail about the importance of diligently focusing on a small number of goals, and the importance of deliberate practice in developing skills fast. Erez certainly embraces these strategies. But then again, so do I. What strikes me is that there’s something more going on here. It’s as if Erez and I are, in some profound sense, wired differently in the way we choose and develop projects.

Put another way, he has an instinct for impact that I seem to lack.

At least, for now.

One of my new obsessions is decoding this instinct — how it works, and more importantly, how to cultivate it.

Failed Attempts to Dismiss the Impact Instinct

Let’s start by considering a pair of obvious explanations for Erez’s impact.

An easy dismissal is to defer to brilliance . Perhaps his secret is that he applies an absurd amount of brain power to solve important problems that stump his peers. If this is true, then there’s nothing easily replicatible about the impact instinct.

Fortunately, a closer look at his Nature paper falsifies this hypothesis. The result in the paper is shockingly straightforward: easy mathematics applied in a very natural way. (Erez even uses the word “simple” in the paper’s title to emphasis its lack of technical fireworks.) It was the basic concept he presented, in the way he presented it, at the time that he presented it, that mattered here.

Another easy dismissal is to defer to luck . Maybe he stumbled into an easy problem at the exact right time and is now reaping the unexpected windfall. If true, this too would yield a non-replicatible explanation for his success.

Fortunately, a closer look at Erez’s publication record falsifies this hypothesis as well. It turns out that he’s repeated this feat of producing a big impact result on two more occasions since his first breakthrough. Not only were these subsequent results in two different fields – molecular biology, and the quantitative study of culture – the corresponding papers both made the cover of Science – an absurd success rate!

If we cannot easily dismiss Erez’s instinct as something impossible to replicate, we are left with a pressing question: what does matter?

Decoding the Impact Instinct

I don’t have a definitive answer to the above question, but I’m starting to circle around some likely suspects. Something that definitely catches my attention at this point are the specifics of Erez’s training.

Erez trained under Eric Lander, the MacArthur Genius Grant-winning director of the Harvard/MIT Broad Institute. Lander is an Oxford-trained mathematician who helped spark the convergence of math and biology that led to breakthroughs like the sequencing of the human genome. He’s arguably the world’s top expert on applying mathematics to new areas of biology in a way that generates high impact results.

Training under Lander, a young Erez would have been taught exactly what type of novel interdisciplinary results cross the threshold required to publish in Nature, and how to write and promote such results in a way that demands attention. (In fact, in my new book on remarkable careers, which comes out this September, I profile a hotshot young Harvard professor who, like Erez, also mixes mathematics and biology in attention-cathcing ways, and who also did a postdoc in Lander’s lab. She too made her reputation with an influential Nature article while still working under Lander.)

I have no idea, for example, how to take the computer science result I’m working on and shape it so that it can be published in a top general science venue, like Science or the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, or so that it can gain major press attention like Erez often wins for his results (c.f., this cover article in the New York Times). To me, to attempt to do so seems like a wasted, hubristic effort.

Hypothetically, however, if Eric Lander revealed himself as a huge Study Hacks fan, and flew down to D.C. to personally coach me, I wonder if these goals would suddenly become plausible?

In some sense, on a smaller scale, I might already be benefiting from a similar coaching advantage. I frequently publish at a conference called PODC, which is a top venue in my niche of distributed algorithm theory. It undoubtedly helps that my PhD advisor at MIT founded the conference. My whole graduate training was oriented around the goal of “writing PODC papers,” much in the same way I assume Erez’s training was oriented around “writing attention-catching Nature and Science papers.”

If this training-centric hypothesis is correct, it bring us back to my recent interest in avoiding pseudo-striving and embracing reality-based planning. Lots of very smart researchers want to replicate the type of success enjoyed by Erez Aiden Liberman, and most work just as hard. But they’ve failed to put an equal emphasis on figuring out how to direct this energy toward impact. We all chat casually about this topic, but what I see in Erez is a systematic, non-obvious, difficult training in these realities.

We can’t all go work with our fields’ equivalents of Eric Lander, but I don’t think this prevents us from learning the same lessons about producing impact. My optimistic contention is that if we apply a touch of the journalistic to our careers — systematically studying, without bias toward what we want to hear, the reality of how our colleagues gain notice — we can hone the type of instinct that Erez deploys so effortlessly.

Bottom Line: There’s no magic in how these stars become remarkable, but there’s nothing simple here either. Stand outs like Erez were trained by world experts in how to produce impactful results in their field. This training is crucial and non-obvious. If we don’t work hard to replicate it, we cannot expect to replicate its results.

###

I’ll talk more about my new book as we get closer to the September publication date, but if you’re interested in learning more in the meantime, check out Publisher Weekly’s nice review, which came out earlier this week, or this recent Wall Street Journal article that quotes me on some of the book’s ideas.

(Photo of Erez at TED Boston by Ritterman)

May 17, 2012

Some More Thoughts on Grad School

Re-Reflection

In 2009, as I was approaching the end of my Phd program, I wrote a blog post titled, Some Thoughts on Grad School. It described lessons I learned during my time at MIT.

Since then, I’ve received many requests to revisit the theme. Now that I’m a professor — albeit a new one — I thought I’d once again reflect publicly on what I did well and what I wish I’d done better.

With this in mind, I want to offer a pair of thoughts on a topic of particular importance to my path as an academic: complexity.

Thought #1: Avoid Complexity When Seeking Problems

Early in my graduate school experience, I had a mentor named Rachid — a well-known distributed algorithm specialist from EPFL. I learned many things from Rachid. For example, I once asked him for advice on a summer internship I was considering. I made different arguments about the value of gaining connections and learning about industry.

“If you want my personal opinion,” he replied, “your time is better spent at MIT, preparing the next STOC/SOSP/JACM paper.”

To put this in context: STOC, SOSP, and JACM are acronyms for some of the most elite conferences and journals in the field of computer science. The lesson Rachid offered — which I’ve since strongly embraced — is that in the end, hard results are all that count.

But the Rachid lesson I want to emphasize here is about the danger of complexity. His approach was to always reduce a problem to its purest, most simple form. This is what leads to true understanding of the mathematical reality underlying the issue, he believed. Once you’re armed with this understanding, you can then, and only then, add back details (and the complexity they require) with confidence.

If you want to see this philosophy in action, take a look at this paper I co-authored with Rachid and another graduate student from MIT. The big picture problem that interested us was messy: how do parties work together to solve problems when their only means of communication is a broadcast channel where a malicious adversary can both jam and spoof messages?

You’ll notice in the paper, however, that we immediately reduce this down to the simplest possible expression of what makes this setting difficult: two players, Alice and Bob, trying to communicate a single bit, while a third player, Collin (the collider), tries to disrupt things.

All of the results in the paper build on our deep understanding of this simple three-player game.

(For what it’s worth, the paper has since been cited around 50 times.)

The problem here is that most graduate students tend toward the opposite of this approach. Their biggest fear is that they’ll propose a result and someone more knowledgeable will look at it, declare it “trivial,” and therefore validate their nagging imposter syndrome. Accordingly, students tend to rush to add technical complexity right away, as if a page full of math validates their ability.

This approach is flawed because it’s hard to make an impact in a technical field without deep understanding, and it’s hard to build deep understand of anything that’s not dead simple to describe. This is why the most respected professors are often those who are most likely to interrupt you and say, “slow down, and explain this to me like I don’t understand anything.”

They don’t want equations, they want insight.

Bottom Line: Hold off complexity as long as possible when studying a problem. It will inevitably enter the scene, but the later the entrance, the more insight you’ll develop.

Thought #2: Seek Complexity in Your Technical Skills

My first thought concerned something I think I do pretty well. My second thought concerns something I didn’t do enough as a graduate student, and that I’m only now, painfully, learning to embrace.

The value of a graduate student (not to mention, an assistant professor), I’ve come to realize, is directly proportional to the quantity and complexity of their technical tool kit. If you study algorithms, for example, the more corners of the literature you’ve mastered, and the more mathematical analysis techniques you’re comfortable with, the more problems you’ll be able to solve. And the more problems you’re able to solve, the more likely that you’ll solve some hard ones — the key currency for an academic career.

This thought doesn’t contradict the first thought (though it might seem to). When tackling a problem, you want to start with its simplest expression. To find a good problem and then make sense of its simplest expression, however, you need the most powerful possible combination of knowledge and skills.

The trickiness here is that mastering new knowledge and learning new technical skills is like learning to play a new instrument: it’s difficult, and frustrating, and takes a long time.

All graduate students are forced to develop a basic tool kit due to the deliberate practice required to pass your courses and contribute to your first publications. The students that thrive, however, don’t stop there; they keep pushing themselves to learn more.

I didn’t do nearly enough of this.

It took me two years to get decent at solving a certain class of problems concerning deterministic distributed algorithms (roughly 2004 – 2006). There was then a two year period where I was satisfied to use only this hammer and go seek nails, no matter how hard they became to find.

The issue I faced was that my field was moving forward. Randomization was where the interesting new work was being done, and my approach was in danger of becoming dated.

It wasn’t until 2008 that I began the dreary effort of teaching myself probability theory. In this early paper, for example, you can see the beginning of the transition: the majority of the results are deterministic, but they draw on a tentative, randomized sub-routine. (This is where, for example, I reintroduced myself to Dr. Chernoff).

The next year I published this paper, which pushed me forward in my learning, but was also a terrible strain. A significant fraction of its results came from the following process:

I would get stuck because I didn’t know enough probability theory.

I would go talk with one of my co-authors, who would reply by filling a white board with a bunch of inequalities.

I would scramble back to my office and try to recreate the argument from scratch, filling in the details, before it slipped my mind.

I would return to my co-author to discover that I had fouled up my dependencies in some terrible way that would likely involve the intervention of something called a “Martingale.”

This was pretty brutal. But I learned quite a bit.

I am realizing now, however, that my pace was still too slow. For example, I should have shot past independent probabilities and mastered techniques for bounded dependence. This is a natural — though difficult — next step that I avoided for too long.

Over the past year, I’ve been systematically increasing my pace of skill learning (more on this soon), but if I had committed to this mindset with more purpose back in 2006, I’m embarrassed to think about the extraordinary impact on my work it might have had by now.

Bottom Line: Treat your time as a graduate student like a professional musician treats his or her performance repertoire. If you’re not constantly straining yourself to learn more and perform better, you’re in danger of being left behind.

(Photo by Nietnagel)

May 7, 2012

Facebook’s COO Works Less Than You

The Fixed Schedule Phenom

Sheryl Sandberg is the COO at Facebook.

Last year she was paid over $30 million dollars in stocks and salary.

This year she was named to Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World list.

But here’s what interests me most: in April she revealed that she leaves work every day by 5:30. She has practiced this habit since she first had kids, but only recently did she build enough confidence to talk publicly about it.

This is a fantastic example of the fixed-schedule productivity philosophy that I’ve long preached. As many have discovered, fixing strong constraints in your working life can paradoxically make your work much stronger (as it forces you to focus on what’s important, which in turn helps you get better at what you do).

E-mailing during every waking hour might make you feel more important, but as Sandberg’s accomplishments verify, it has very little to do with your actual impact.

###

Speaking of interesting articles, my friend Elizabeth Saunders has a thought-provoking piece on the Harvard Business Review blog about the different types of passion and their implication for our working lives.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers