Impact Algorithms: Strategies Remarkable People Use to Accomplish Remarkable Things

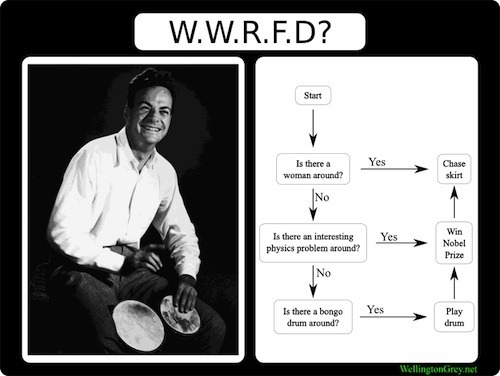

(Image from WellingtonGrey.net via c2.com)

Impact Algorithms

I’ve been writing recently about the impact instinct — the ability to consistently steer your work somewhere remarkable. We know that diligently focusing on a single general direction and then applying deliberate practice to systematically become more skilled, are both crucial for standing out. But true remarkability seems to also require this extra push.

Since writing these posts, readers have sent me an amazing collection of quotes and articles that provide supporting details for this idea. Reviewing these resources, I noticed that the following systematic strategies — let’s call them algorithms — seem to pop up again and again.

Below, I summarize these algorithms, each of which I named for someone remarkable who exemplifies it: I don’t know that they’re all right; I don’t know which work best; but they should provide nuance to our understanding of the impact instinct.

The Feynman Algorithm

Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman is a master of impact. Many people have attempted to understand his curiously successful approach (e.g., this wonderful collection of quotes that a reader sent me). Of the many candidates that might rightfully be called the “Feynman Algorithm,” here’s the one I think played the biggest role in his success:

Simplify the problem down to an “essential puzzle.” Here’s how Danny Hillis explained Feynman’s use of simplicity: “He always started by asking very basic questions like, ‘What is the simplest example?’ or ‘How can you tell if the answer is right?’ He asked questions until he reduced the problem to some essential puzzle that he thought he would be able to solve. Then he would set to work.” (Notice, the importance of simplicity is something we’ve encountered before.)

Continually master new techniques and then apply them to your library of unsolved puzzles to see if they help. As mathematician Gian Carlo-Rota explained when describing Feynman’s use of this strategy: “Every once in a while there will be a hit, and people will say: ‘How did he do it? He must be a genius!’” (Notice, it’s at this step of the Feynman algorithm that we see the value of ultra-learning.)

The Thrun Algorithm

Computer scientist Sebastian Thrun rocketed to fame when his self-driving car won the Darpa Grand Challenge (though his fame among roboticists long preceded that particular public victory). He now runs Google X, the search company’s skunk works for big impact projects.

Studying Thrun’s story, the following algorithm seems to be at the core of his remarkable accomplishments:

Pick a problem that matters. According to a recent Wall Street Journal profile of Thurn: “His mentor at CMU, Tom Mitchell, told him, ‘Pick a problem that matters to society.’ So he helped create robots, including a “nursebot” to assist the elderly in nursing homes and robotic tour guides…these were hard projects, [Thrun] says. ‘Just let go, trust your ability to learn, more [than] holding on to the things you’ve achieved—and that became the central theme in my life.’”

Stick to it. The problems picked by start researchers who use the Thrun algorithm tend to be surprisingly generic — e.g., create robots that are good for society — but their clarity drives people to learn hard things, make hard connections, and wring the most out of their ability. This sounds obvious, but it really isn’t. The default behavior is, as Thrun warned, to “[hold] on to the things you’ve achieved.” Something needs to push you to keep breaking new ground.

The Erez Algorithm

Study Hacks readers know that Erez Lieberman Aiden, a hotshot young researcher out of Harvard, is my favorite example of the impact instinct. Recently, I’ve heard from several readers who know Erez, his advisors, and/or his academic field. They pointed me toward the following important algorithm that he seems to use to great advantage:

Be Confident. “I knew Erez before he was a grad student,” a reader told me. “And he was extremely confident then. Confidence and boldness pay off enormously in academia.”

If You’re Not Confident, Do Everything You Can to Surround Yourself With People Who Are. This leaves the question of how one becomes confident. In the academic context, the readers who wrote me agreed that this confidence comes from surrounding yourself with people who are already doing remarkable things. “The cultural context here is really, really important,” said one reader. “Eric Lander and Martin Nowak [Erez's mentors] are powerful.” Another reader agreed: “These folks have grown up in groups/labs in which high impact papers are the norm. Not only do you pick up on how high-impact papers are written, but perhaps more importantly you develop the attitude that of course you can make high impact, such papers are something perfectly within your reach because they were routine in your scientific babyhood.”

This Might Mean Getting “Good Grades.” We tend to separate remarkable accomplishments from conformist behaviors like studying hard, as the quest to become remarkable seems inherently rebellious. But a corollary to step 2 from above is that surrounding yourself with confident people often requires that you first jump through well-established hoops. If a freshman tells you that she wants to do research that will change the world, don’t tell her to go find a life changing project — she’s way too early in her development to successful apply the Thurn Algorithm — instead tell her to earn the best possible grades, so she can can make her way into a great graduate school, learn from the best people, and be surrounded by the most confident researchers. This is the foundation that produces remarkable things.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers