Cal Newport's Blog, page 32

January 16, 2018

On Seriously Rethinking the Digital Economy

A Diamond in the Economic Rough

Two weeks ago, the American Economic Association held its annual meeting in Philadelphia. Spread over three days and two different hotels, this conference included over 500 sessions.

Buried in the program, during the morning on the last day, was a grab bag paper session titled Radically Rethinking Economic Policy. The final paper discussed in this session should command our attention, because its coauthors include, in addition to four well-respected economics researchers, someone who I’ve long promoted as one of the most brilliant and outrageous thinkers pondering the digital world: Jaron Lanier.

The paper, which is titled “Should We Treat Data as Labor? Moving Beyond ‘Free’,” translates the basic premises of Lanier’s 2013 book, Who Owns the Future?, into more precise economic terminology.

This short paper contains many points worthy of longer discussion. I’ll focus here on its main conceit.

The authors note that a core resource of the digital economy is the data produced by users of services like Facebook and Google, which can then be used to train machine learning algorithms to do valuable things like precisely targeting advertisements or more accurately processing natural language.

The current market treats data as capital: the “natural exhaust from consumption to be collected by firms” for use in training their AI-driven golden gooses.

Lanier and company suggest an alternative: data as labor. Put simply, if a major platform monopoly wants your data to help build a multi-billion dollar empire, they must pay you for it. Offering a free service in return is not enough.

The idea of treating data as labor, which might require massive intervention in the form of user unions and government regulation, is an example of a radical market, an emerging concept in economic theory in which new markets are constructed specifically to act as countervailing forces to existing markets that are causing trouble.

To Lanier et. al., the data as labor radical market could defend against our worse fears about AI stealing our jobs by more equitably distributing the spoils of this next technological boom — supporting a middle class of “data workers” who find dignified employment in providing the quality data the boom will require.

To be clear, I’m not fully convinced. As Lanier himself admits, more formal analysis is needed to explore whether the vague notion of a dignified data worker class is actually feasible (regardless of the difficulties inherent in enforcing such a system). But I love the discussion.

The attention economy is not a minor bubble or teen fad, it’s a major force in our society that deserves the type of serious analysis that thinkers like Lanier and his economist coauthors are demonstrating. I hope this trend of careful but radical thinking continues.

#####

For a nice introduction to Lanier, I suggest Ezra Klein’s recent podcast interview, as well as Lanier’s epochal 2010 manifesto, You Are Not a Gadget. He also just published an acclaimed memoir titled Dawn of the New Everything.

(Photo by Luca Vanzella.)

January 12, 2018

On the Rise of Digital Addiction Activism

The First Stirrings of a New Activism

The investment funds run by Jana Partners and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System hold a combined $2 billion in Apple stock. This ensured the business community took notice when earlier this week, these investors sent a letter to Apple expressing concern about the impact of the tech giant’s products on young people.

To quote the letter:

“More than 10 years after the iPhone’s release, it is a cliché to point out the ubiquity of Apple’s devices among children and teenagers, as well as the attendant growth in social media use by this group. What is less well known is that there is a growing body of evidence that, for at least some of the most frequent young users, this may be having unintentional negative consequences.”

The investors go on to make several recommendations, including the convening of a committee of experts to study the issue, the introduction of better parental controls, and the funding of more research.

This letter received significant coverage this week so I don’t want to belabor its points or overhype its significance ($2 billion doesn’t provide that much leverage against a $900 billion Apple market cap).

But I’ve been asked about it quite a bit, so I thought I would share a few initial reactions…

Apple is the wrong target.

The iPhone was not designed to be addictive. Indeed, as part of my research for the book I’m writing on digital minimalism, I spoke with one of the original iPhone team members, who told me that Steve Jobs never envisioned this device to be something that you checked constantly. The original vision for the iPhone was built around two surprisingly quaint goals: (1) it would be a much better mobile phone than anything else on the market; (2) it would prevent the need to carry a separate iPod along with your phone.

The addiction ensnaring children is not some master plan secretly hatched at Apple, but is instead the spawn of attention economy conglomerates like Facebook, who, unlike Apple, directly profit from compulsive use, and leverage the iPhone merely as a convenient platform.

I predict a large shift in how our culture thinks about children and smartphones.

The investor letter to Apple explains: “To be clear, we are not advocating an all or nothing approach [when it comes to children and smartphones].” I think they’re being too cautious. My techno-skeptic spider sense is telling me that we might soon see a shift in our culture where it becomes normal for kids to receive their first smartphone at the age of 18. The algorithmically-enchanced addictiveness delivered through these mobile platforms, like the chemically-enhanced nicotine in tobacco products, increasingly seems too potent for developing minds.

I hope to see alternatives to the attention economy business model.

At the core of almost everything negative about the smartphone era is the attention economy business model, which depends on getting a massive number of people to use free products for as many minutes as possible. This model, of course, dates back to the beginning of mass media, but the combination of big data and machine learning techniques, along with careful attention engineering, has made many modern apps too good at their objective of hijacking your mind — leaving users feeling exhausted and unnerved at their perceived loss of autonomy.

I think there’s an interesting opportunity here for start-ups to explore alternative business models that reward value more than raw usage (think: paid subscription). This opportunity is especially ripe in the context of social media, where the great Web 2.0 promise of digitally-enabled expression and connection was tragically diluted by the aggressive brain hacking tactics that now define so much of the user experience in this space.

It might be hard to create a publicly traded unicorn with one of these alternative models (due to network effects, a disruptive startup of this type would probably have to focus on smaller, niche communities), but you could still create something quite lucrative for those involved while remaining more ethical (c.f., Matthew Crawford for more on the ethics of attention).

December 31, 2017

Tycho Brahe’s Cognitive Kingdom

Deep (Work) History

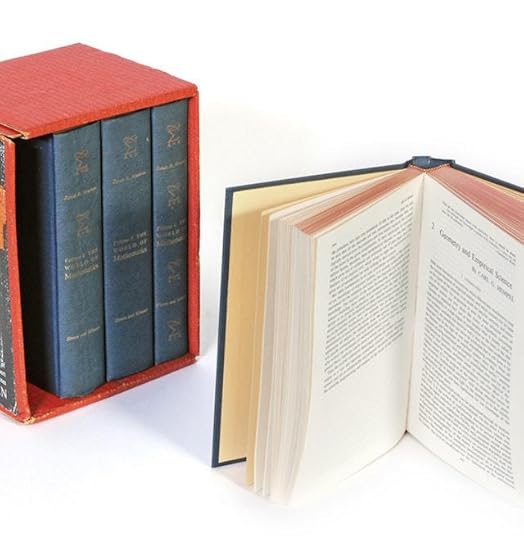

Recently, I’ve been reading through the first volume of Simon and Schusters’ magisterial 1954 four-volume essay collection, The World of Mathematics (edited by James Newman). In a chapter on Napier’s discovery of logarithms, written by Herbert Turnbull, I came across a neat story about the great Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe that I hadn’t hear before.

I thought I would share it.

In the sixteenth century, Brahe’s reputation and service had earned him the respect of the Danish King Frederick II. Wanting to reward Brache, Frederick offered Brache his choice of castles to rule.

Brahe, however, had no interest in the administrative responsibilities that came along with such holdings, writing: ” I am displeased with society here, customary forms and the whole rubbish.” He wanted instead to dedicate his life to science.

So Frederick made a better offer: he would give Frederick the island of Hven, located in the narrow straight between modern-day Copenhagen and Helsingborg, as well as the funding to build on it a grand observatory, which Brahe came to call Uraniborg — the Castle of Heavens.

As Turnbull reports: “Brahe…reigned in great pomp over his sea-girt domain,” making it into a palace of science where he could retreat and work deeply on his astronomical musings.

I don’t have any major conclusions to draw from this story other than the fact that it’s a nice piece of deep work lore — the type of contemplative nostalgia that warms the heart on a cold distracted winter afternoon.

(Also, if you’re looking to buy me a Christmas present, you could do worse than to follow King Frederick’s lead. Though, if I’m being honest, I might prefer my island somewhere a little warmer…)

December 20, 2017

The End of Facebook’s Ubiquity?

A Self-Defeating Statement

Last week, Facebook posted an essay on their company blog titled: “Hard Questions: Is Spending Time on Social Media Bad for Us?” The statement confronts this blunt prompt, admitting that social media can be harmful, and then exploring uses that research indicates are more positive.

Here’s the relevant summary of their survey:

“In general, when people spend a lot of time passively consuming information — reading but not interacting with people — they report feeling worse afterward…On the other hand, actively interacting with people — especially sharing messages, posts and comments with close friends and reminiscing about past interactions — is linked to improvements in well-being.”

From a social perspective, Facebook should be applauded for finally admitting that their product can cause harm (even if they were essentially forced into this defensive crouch by multiple recent high level defectors).

From a business perspective, however, I think this strategy may mark the beginning of the end of this social network’s ubiquity.

Concrete Competition

Until last week’s statement, Facebook’s messaging embraced an ambiguous mix of futurism and general-purpose positive feelings (their mission statement describes themselves as a tool “to give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together,” whatever that means).

The company promoted the idea that they’re a fundamental technology, as much a part of the fabric of society as electricity or the internet itself. From this foundation, it was easy for the company’s supporters to dismiss critics as either anti-technology eccentrics or anti-progress conservatives (I speak from personal experience) .

As I’ve written before, however, once a social media company like Facebook starts talking about specific uses of their tool, and tries to quantify the value of these uses, they enter a competitive arena in which they probably won’t fare well.

In its statement, for example, Facebook emphasizes that using their service to “actively engage” with “close friends” can generate measurable increases in well-being in research studies.

But once they enter this concrete debate it’s natural to start asking how much does this lightweight digital interaction increase well-being, and then compare these benefits to the numerous other ways one might seek to actively engage close friends.

I haven’t conducted this study, but I suspect that the benefits of a semi-regular beer with a good friend absolutely dominate the benefits generated by half-heartedly tapping out emojis on the friend’s wall while waiting out Hulu advertisements.

Put another way, once social media services are forced to make a sales pitch, as oppose to leveraging an inherited position of cultural ubiquity, they suddenly seem so much less vital. It’s not that these services are useless. But when considered objectively, they fall well short of earning the default status that they both currently enjoy and rely on for their high-volume attention economy business models.

Which all leads to the conclusion that 2017 is shaping up to be an unusually bad year for Mark Zuckerberg.

December 14, 2017

BuJoPro: Thoughts on Adapting Bullet Journal to a Hyper-Connected World

Analog Productivity

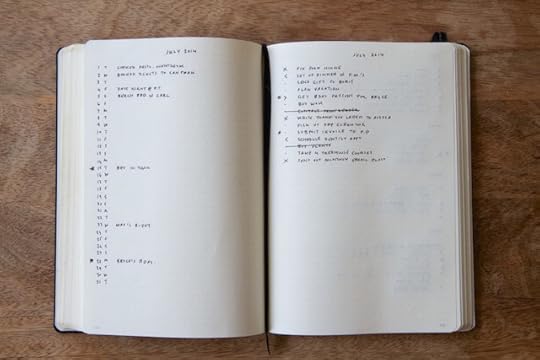

Bullet Journal (BuJo for short) is a personal productivity system invented by a product designer named Ryder Carroll. You can find a detailed introduction to BuJo on its official web site, but I can provide you the short summary here.

The system lives entirely within an old-fashioned paper notebook. Each day you dedicate a page of the notebook to a daily log in which you create a bulleted list of tasks and events. As the day unfolds, you use shorthand marks to indicate a task is complete or needs to be migrated to a different day.

You can also take brief notes about the day, and, if needed, hijack multiple pages for more extensive musing. The next daily log can live on the next available page. (This idea that you format notebook pages on demand instead of in advance is fundamental to BuJo.)

There are some standard pages most BuJo notebooks include in addition to the daily log entries. An index at the front of the notebook is used to keep track of how the pages are being used. You grow the index as you fill the notebook. Each month also gets its own monthly overview and task list that are used to inform how you schedule individual days. And so on.

A good way to think about BuJo is basically a less-rigid version of the Franklin Planner system.

BuJo for the Overloaded

A lot of readers have asked me about BuJo so I thought I would share some thoughts.

First, I want to emphasize what I really like about the system. Its largely unstructured use of a blank notebook is a brilliant example of low-friction freestyle productivity. In my experience, these types of systems are much more likely to persist than those that require more involved constraints.

I also love BuJo’s embrace of paper as a fantastically flexible technology. A typical notebook in this system uses many different formats, conventions and notations — many of which might be custom to the individual user and change rapidly over time. This would be prohibitively difficult to implement in a digital tool.

Also: notebooks don’t need batteries.

My main concern, however, is that this system, as traditionally deployed, cannot keep up with the complexity and volume of demands that define many modern knowledge work jobs, where the sheer volume of tasks you must juggle, or calendar events in a typical week, might overwhelm any attempt to exist entirely within a world of concise and neatly transcribed notebook pages.

With this in mind, I’ve been brainstorming recently about how one might upgrade the rules of BuJo to better handle these unique demands, while still keeping the features I really like about the original framework — creating, for lack of a better term, a BuJoPro system.

Here are some of the ideas I had about shifting from BuJo to some notion of BuJoPro…

Introduce weekly plans. In BuJo, you create a list of tasks and key events for the current month, and then use these pages to inform the plans on each daily log page. In BuJoPro, you should also put aside a page for a weekly plan at the beginning of each week. Use this plan to confront what you’ve already scheduled for the week and what you want to do with the remaining free time. It’s common for weekly plans to change; when this occurs, update the plan. If the changes are significant, create a new weekly plan on the next available page, this new plan can cover the days that remain in the week. (See here for more on weekly planning.)

Time block daily plans. In BuJo, each day is driven by a daily log page that contains a list of tasks and events. As longtime readers know, I am not a fan of using lists to dictate your behavior. It’s much more effective to block out the hours of your day and assign them to specific efforts. This time blocking strategy provides a much more realistic assessment of how much time you really have free and allows you more control in optimizing your use of this time. This doesn’t mean, of course, that every waking minute must be scheduled. Effective time blockers tend to to block out all hours during the work day, and then fall back to a more informal plan for their hours outside work. (See here for more on time blocking.)

Maintain a deep work tally. Once you’re time blocking every day, it’s easy to use BuJo-style shorthand to track deep work hours. I recommend circling each hour in your daily plan during which you maintained unbroken concentration on a demanding task. When summarizing your week or month it’s then easy to quickly tabulate how many of your work hours were spent in a state of depth — a compelling scoreboard that helps ensure you’re producing value, and not just reacting to demands.

Augment the notebook with a calendar and master task list. The beauty of BuJo is that it exists within a single self-contained notebook. This feature, however, can also be a fatal flaw. Many knowledge workers unavoidably fragment their week with dozens of shifting appointments and meetings. There’s no way to manage this easily in a paper notebook — it’s simply much more effective to use a digital calendar. Similarly, as David Allen famously argues, many modern professionals must keep track of hundreds of professional tasks. These cannot effectively exist in a paper notebook on a monthly task list — it’s simply more effective to maintain a digital list. In BuJoPro, therefore, you should reference a digital calendar and master task list each week when creating your weekly plan. As your week unfolds, you can then mainly live within your analog notebook.

Integrate email. Probably the biggest omission from BuJo in the professional setting is that it ignores the (unfortunate) reality that most knowledge workers drive their work day by sending and receiving emails. There must be, therefore, a considerate process for interfacing between an email inbox and paper notebook. In BuJoPro, the digital calendar and master task list can mediate between these two worlds. That is, as you check your inbox, you can add new events or deadlines to your calendar, and new tasks to your master task list. Because you check your calendar and master list during the weekly planning process, these updates will integrate into your paper scheduling as needed. If something pops up in your inbox that impacts the current week, you can directly modify the current weekly and/or daily log as needed to integrate the change.

Caveat emptor: I haven’t field tested BuJoPro. The above ideas are merely speculation on how one might maintain all the things I love about the self-contained analog simplicity of BuJo, while successfully tackling the annoying challenges unique to our current hyper-connected world.

(I should also note that “BuJo” is a registered trademark, while “BuJoPro” is just a term I made up that has no official connection to any official Bullet Journal enterprises.)

December 10, 2017

Jocko Willink On the Power of Discipline

On Doing Less to Get More

Jocko Willink is an intimidating looking man (see above). He’s also intimidatingly impressive. He’s a former Navy Seal who was awarded a Bronze and Silver Star in Iraq while leading Task Force Bruiser: the most decorated special forces unit in that war. He recently wrote a business bestseller called Extreme Ownership and now does leadership consulting.

He has a new book out and its title caught my attention: Discipline Equals Freedom.

I haven’t read the book yet, but I did listen to Jocko’s interview with the always-sharp Ryan Michler. Here’s how Jocko explained his book’s theme early in the discussion:

“If you want freedom, then you need to have discipline…the more discipline you have in your life the more you’ll be able to do what you want. That’s not true initially; initially the discipline might be things you don’t want to do at the time, but the more you do things that you don’t want to do, the more you do the right things, the better off you’ll be and the more freedom you’ll have…”

Jocko’s examples of this idea in action mainly concerned personal development. More discipline with your finances, for example, will eventually yield more financial freedom, while more discipline with time management will allow you to do more interesting things with your time.

As I listened to the interview, however, I was struck by the thought that his concept might also prove relevant to the seemingly less related context of digital knowledge work.

The front office IT revolution granted the knowledge worker an amazing amount of apparent new freedom: email made communication with anyone about anything instantaneous; the world wide web put all information at their fingertips; the mobile revolution allowed them to take these promethean gifts with them everywhere.

But as I discussed in my recent post on stagnant economic productivity, this apparent freedom is yielding mixed results. And I can’t help but wonder if Jocko’s wisdom hints at an alternative vision.

The new economy does offer exciting new opportunities, but perhaps the most effective way to unlock this freedom in the long term is to be more disciplined in the short term, especially when it comes to your time and attention: to focus relentlessly on producing the things you know how to do best at the highest possible level of quality, while ignoring the attractive digital baubles that promise you conveniences and the potential of breakthrough connections and exposure.

As Jocko put it: “do things you don’t want to do…do the right things,” and trust this discipline now will eventually generate the freedom you seek.

November 30, 2017

On the Complicated Economics of Attention Capital

A Serious Consideration

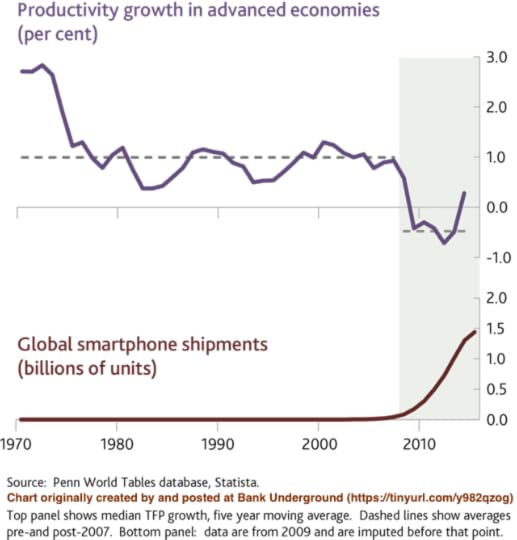

In recent years, I’ve occasionally tackled an intriguing question: are distracting technologies partially to blame for our economy’s sluggish productivity numbers?

I’m often tentative about addressing this topic because I’m not an economist, and serious economists seem to have other explanations in mind (c.f., this column or this book).

This is why I was pleased when many of you forwarded me an article titled: “Is the economy suffering from the crisis of attention?” It’s written by Dan Nixon, a (serious) economist at the Bank of England.

In this article, Nixon explores the question I asked above. In doing so, he outlines two main “channels” through which the new technologies of the Network Age might impact economic productivity indicators:

Channel #1: These technologies can distract employees from their actual work. If you spend less time working, and more time skimming your Facebook newsfeed, you get less done.

Channel #2: These technologies can directly and permanently reduce the rate at which employees produce value using their brains. If your workflow requires you to constantly check emails, then your ability to create new value is dampened.

My suspicion is that the second channel is the main culprit. As I’ve argued before (c.f., this article I wrote for HBR.org), the front office IT revolution, in which we hooked knowledge workers together with high-speed communication networks, has been a mixed blessing.

We assumed that slow communication and inadequate information was a primary bottleneck for knowledge work. But reality proved more complicated. As we’re learning, extracting a good return on investments in “attention capital” (to use a term from Nixon) requires that you balance two things:

providing your employees’ brains timely access to the right information; and

providing these brains the right conditions under which to process this information effectively.

The front office IT revolution has focused almost exclusively on the first item from this list by prioritizing faster networks and more efficient communications tools — a movement that has reached an apex in our current age of ubiquitous mobile access to all people and all information.

And yet, even though we’ve pushed connectivity to daring new levels — a technological miracle built on numerous ingenious innovations — we haven’t become more productive. In fact, the better these tools get, the less productive we become! (See the above chart, which is from Nixon’s article).

A Tricky Balance

The problem, I conjecture, is that focusing exclusively on the first item from my list has generated a perverse counteraction: not only does it steal our attention from the equally important emphasis on optimizing cognitive operating conditions, it actually makes these conditions worse. The result: productivity stagnates.

I increasingly believe that it’s exactly this dynamic that makes it so hard to figure out how to make effective use of attention capital.

If we ignore the conditions in which we expect brains to produce value, we cannot expect productivity to increase. At the same time, if we focus only on enabling deep thinking, these brains might not have the right information to think about, also hurting productivity.

Figuring out this balance is perhaps the most pressing question concerning continued growth of the knowledge work sector.

Or maybe it’s not. Which brings me back to Dan Nixon. What I especially like about his article is that he ends with a call for serious experimentation to get to the bottom of these issues.

“Ideally we would want to observe directly how ‘attention capital’ and productivity vary across firms and over time,” he writes.

I agree. Writers like me have been pontificating cleverly on these issues for years, but real progress will require more data.

Hopefully there are some economists out there ready to take on Dan Nixon’s challenge.

#####

Speaking of attention capital, one of my favorite start ups, Mouse Books , just announced a Kickstarter campaign for their holiday edition. The perfect gift, in my opinion, for the deep thinker in your life.

November 21, 2017

The Woodworker Who Quit Email

The Disconnected Craftsman

Christopher Schwarz is a master furniture maker. In addition to working on commissioned pieces in his Kentucky storefront, he’s the editor of a press that publishes books on hand tool woodworking. In his spare time, he researchers traditional woodworking techniques.

In short, Schwarz is a classic craftsman. If you want to ask him about his trade, however, you’ll have a hard time getting in touch. In 2015, he stopped using (public) email. And he has no intention of going back.

As Schwarz elaborated in a recent essay, this decision upset some customers, some of whom tried to find ways around his no email policy by tracking down his personal address, or using the customer service address for his publishing company.

Here’s Schwarz’s blunt response to these efforts:

Please don’t waste your breath, your fingers or your 1s and 0s. These messages are all simply deleted. I know deleting them might seem rude. And some of you have told us how rude you think it is in long rants… which get deleted.

As he then explained:

Trust me. It’s not you. It’s me. I had multiple public email addresses for 17 years and answered every damn question sent to me…It was all too much. I was spending hours each day answering emails. It cut into my time researching, building, editing and writing (not to mention time with my family).

So he quit: he deleted his inbox, then deleted his accounts, and finally told people that if they really needed to ask him questions or solicit advice they could come by his store in Kentucky. If they couldn’t make the trip then they’d just have to move on with their life.

A Crafty Thought Process

Schwarz’s story heartens me. I don’t think that most people could replicate his decision to leave email. But I do think more people could follow the thought process that led to this decision (even if the specifics of their conclusions might differ).

In more detail, what impresses me about Schwarz is that he rejected the fear of missing out — on a new lead, on a new opportunity, on a new fan — that permeates so much of our digital age business culture, and started instead from a simpler question: how do I get better at what I do best?

Honest answers to this query rarely involve spending more time online.

#####

If you’re attracted to the idea of an artisan woodworker learning his craft, I recommend the surprisingly thoughtful (and quite aspirational) memoir, Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman.

November 17, 2017

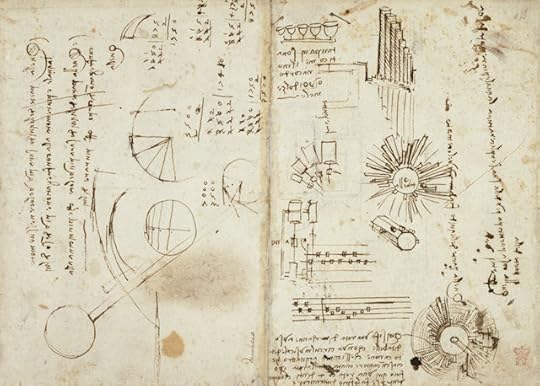

The da Vinci Pause

Leonardo’s Life Hack

Last month, Walter Isaacson released his big new biography of Leonardo da Vinci. I haven’t read it yet (though it’s inevitable I will). In the meantime, I listened to Brett McKay’s sharp podcast interview with Isaacson.

As the conversation winds down, McKay poses an intriguing question:

“[Leonardo] da Vinci lived 500 years ago, Twitter didn’t exit, Instagram didn’t exist, all these digital things that are distracting us, that make it hard to really observe, didn’t exist. So based on your research and writing on da Vinci: what can we learn from him about staying focused and observing intensely on things even in this crazy digital world that we live in?”

Isaacson, who spent years immersed in over 7000 pages of da Vinci’s brilliant, but also scattered and frenetic notebooks, dismissed the premise: “Yeah, he had distractions too.”

So how did da Vinci end up a creative genius still revered 500 years later? Here’s Isaacson’s explanation:

“What he was able to do is pause, and put things aside, and look at very ordinary things and marvel at them.”

In this observation about a past figure is a powerful suggestion for grappling with the endless information deluging our current moment. Technologies like the internet provide everyone the raw material to become a renaissance person, but to take advantage of this reality it helps to cultivate da Vinci’s ability to pause when something catches your attention, and to then give it the intense, deep concentration needed to transform a fleeting spark into something more substantial.

#####

As a self-proclaimed productivity nerd, I thought I’d seen it all when it comes to discussions of time management. But then my longtime friend Elizabeth Grace Saunders proved me wrong. Her new book, Divine Time Management, tackles personal productivity through a novel lens: Christianity. If you’re both Christian and overwhelmed by all you have to do, check out Elizabeth’s latest.

November 9, 2017

Sean Parker on Facebook’s Brain Hacking

A Conscientious Objection

Sean Parker, the founding president of Facebook, was interviewed onstage yesterday at an event held by Axios at the Constitution Center in Philadelphia. The topic was cancer innovation, but the conversation turned at some point to Parker’s time at Facebook during its early years.

Perhaps emboldened by social media’s recent PR problems, Parker, who told Axios co-founder Mike Allen backstage that he had become a “conscientious objector on social media,” was unusually candid.

Here are some of his remarks (as reported this morning by Allen):

“The thought process that went into building these applications, Facebook being the first of them, … was all about: ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?'”

“And that means that we need to sort of give you a little dopamine hit every once in a while, because someone liked or commented on a photo or a post or whatever. And that’s going to get you to contribute more content, and that’s going to get you … more likes and comments.”

“It’s a social-validation feedback loop … exactly the kind of thing that a hacker like myself would come up with, because you’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.”

“The inventors, creators — it’s me, it’s Mark [Zuckerberg], it’s Kevin Systrom on Instagram, it’s all of these people — understood this consciously. And we did it anyway.”

As Parker left the stage, he joked that Mark Zuckerberg was going to block his Facebook account. Perhaps it’s just wistful thinking on my part, but it seems to me that it’s Zuckerberg who should be worried that more and more people might start carrying out this blocking all on their own.

#####

(Hat tip to Pawel and Nwokedi)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers