Cal Newport's Blog, page 31

April 11, 2018

The Disturbing High Modernism of Silicon Valley

A Revealing Memo

A couple weeks ago, BuzzFeed leaked a memo written by Facebook VP Andrew “Boz” Bosworth in the summer of 2016. It contained the following controversial passage:

“[Connecting people] can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools.

And still we connect people.

The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good.”

The reaction to this memo has been muted by the larger data privacy issues afflicting Facebook at the moment, but those who did object, did so mainly on the grounds that Boz was being callous about the potential for this platform to cause harm.

In my opinion, however, this memo contains hints of an even more insidious mindset…

The Disasters of High Modernism

In his new book, Enlightenment Now, Steven Pinker lays out a 550-page argument supporting the core Enlightenment values of reason, science, humanism and progress. Even Pinker, however, is quick to point out the danger of pushing these ideas too far.

Where we’ve gotten in trouble, he notes, is when we “[deny] the existence of human nature, with its messy needs for beauty, nature, tradition and social intimacy” — leading us to believe that we can radically reshape humans through technology and reason alone into a better, more efficient existence.

Political scientist James Scott (the source of Pinker’s comments) calls this movement “High Modernism.” He’s not a fan.

Scott blames the technocratic hubris of High Modernism for some of the great social engineering disasters of the 20th century, from Stalin’s famine-inducing farm collectivization, to our own country’s failed mid-century urban renewal projects, which, to quote Pinker, too often “replaced vibrant neighborhoods with freeways, high-rises, windswept plazas, and brutalist architecture.”

Technology has undoubtedly created massive benefits for humanity. But it can cause problems — shifting into High Modernism territory — when it ignores, or even tries to replace our complex humanity instead of working with it.

All of which brings me back to the Facebook memo…

From Utopia to Dystopia

What scares me about the leaked Facebook memo is not the passage where Boz acknowledges the harm this platform can create, but instead what he says next: “we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good.”

Why is this goal a “de facto good”? Boz elaborates:

“The natural state of the world is not connected. It is not unified. It is fragmented by borders, languages, and increasingly by different products.”

Facebook can fix this. As Boz explains, growing their reach is more important than their stock price and more important than creating great products. “[C]onnecting people. That’s our imperative.”

I read these lines as arguing that the natural state of human interaction is hopelessly irrational and ineffective. Facebook hopes to replace this “fragmented” state of human sociality with something better; something that spans borders and languages; something that offers many more connections; something that can leverage big data and smart AI to direct our relationships in an optimal manner.

This vision is classic High Modernism — merely shifted from city cores and farm fields to the digital realm. It should, therefore, scare the hell out of us.

If you went back in time 15 years, and showed James Scott a draft of Boz’s vision, Scott would almost certainly warn you that an attempt to reshape something as fundamental and messy as human sociality with a “better” technological solution would backfire in unexpected, dark, and painful ways.

This is, of course, exactly what happened. The shift from real to virtual connection paradoxically made people more lonely, depressed, and anxious, while simultaneously sparking unexpected increases in tribalism, authoritarianism, extremism, disinformation, and hyperbolic outrage.

Social media executives seem genuinely surprised by these outcomes, but at the same time, they’re not overly concerned. As Mark Zuckerberg demonstrated in yesterday’s congressional testimony, they see these issues as bugs in their master plan that can be patched with even smarter technology (Zuckerberg’s new hope is that clever AI will save the day).

The study of High Modernism, however, undermines this optimism. The problem with social media’s attempt to improve human sociality is not the details of its implementation, it’s instead the very fact that they’re pursuing such a utopian objective in the first place.

A Tale of Two Motives

This discussion of Silicon Valley’s High Modernist aspirations injects extra complexity into our current cultural conversation surrounding social media.

In writing on this topic, I tend to describe social media companies as cynically addicting users to maximize the data they can then extract, package, and sell. From this perspective, the user is merely a pawn in the game of revenue projections and market expectations. Much of the recent coverage of Facebook’s data privacy issues adopts this perspective.

The Boz memo, however, literally laughs at this notion: “[This] isn’t something we are doing for…our stock price (ha!),” he writes. High modernism is more about perfecting human society than making money.

I think the most accurate thing to say is that both factors are at play and that they combine in complex ways. For a true believer like Boz, who has been at Facebook for a long time, perhaps this vision of upgrading human interaction is his primary driver. Zuckerberg, on the other hand, probably tempers this bold vision with the more pragmatic necessity to please his board from quarter to quarter.

I’ve come to realize that when thinking about social media, it’s important to keep both motives in mind, as they spark different reactions.

When confronting the cynical side of the social media business model (as we’ve all being doing in recent weeks), the relevant follow-up question is pragmatic: How do we prevent these companies from abusing our private data?

When confronting the utopian side, by contrast, the relevant question becomes sharper: Should these companies even exist at all?

March 28, 2018

On Analog Social Media

The Declutter Experiment

In late 2017, as part of my research for a book I’m writing on digital minimalism, I invited my mailing list subscribers to participate in an experiment I called the digital declutter.

The idea was simple. During the month of January, 2018, participants would take a break from “optional technologies” in their lives, including, notably, social media. At the end of the 31-day period, the participants would then rebuild their digital lives starting from a blank slate — only allowing back in technologies for which they could provide a compelling motivation.

I expected around 40 – 50 people would agree to participate in this admittedly disruptive exercise.

My guess was wrong.

More than 1,600 people signed up. We even received national attention when the New York Times wrote a nice article about the experiment.

Since January, I’ve been reading through the hundreds of reports that participants sent me about their experience with the digital declutter. I’ve been learning a lot from these case studies, but I want to focus here on one observation in particular that caught my attention: when freed from standard digital distractions, participants often overhauled their free time in massively positive ways.

Here are some real examples of this behavior from my digital declutter experiment…

–> An engineer named James realized how much of the information he used to consume though social media during the day was “unimportant or useless.” With this drain on his attention removed from his routine, he returned to his old hobby of playing chess, and became an enthusiast of architectural Lego kits (“a wonderful outlet”).

–> Heather, a writer and mother of three homeschooled kids, completed a draft of a book, while also reading “many books” written by others. “I’m recapturing my creative spirit,” she told me.

–> An IT professional named Andy noted that he typically reads 3 – 5 books a year. Free from the time sink of social media, he’s on track to finish 50 books in 2018.

–> Angie is a yoga instructor, but she also has BFA and used to be a professional artist. “Not spending time on social media had me thinking,” she told me, “what do I want to get good at? Making social media posts, or getting back into painting?” She choose painting. During her declutter she booked three new art shows and had her work accepted at a juried exhibition. “For me, it was simply a refocusing of my time and commitment to myself, to get better at something I love,” she said.

–> A retired stockbroker named Bob began to spend more time with his wife, going for walks, and “really listening.” He expanded this habit of trying to “listen more and talk less” to his friends and family more generally.

–> A PhD candidate named Alma described the experience of stepping away from distracting technologies as “liberating.” Her mind began “working all the time,” but on things that were important to her, and not just news about “celebrities and their diets and workouts.” Among other things, she told me: “I was more there for my girls,” I could focus on “keeping my marriage alive,” and at night “I would read research papers [in the time I used to spend scrolling feeds].”

–> Another PhD candidate named Jess tackled Anna Karenina and Infinite Jest during the declutter. “Now that I feel like I’m actively choosing what I do with my downtime, I find [hard] activities like reading more pleasurable.”

–> A government worker named Ari replaced his online news habit with a daily subscription to the Wall Street Journal print edition. “I still feel perfectly up to date with the news, without getting caught up in the minute-to-minute clickbait headlines and sensationalism that is so typical of online news,” he told me.

–> When a publishing executive named Leonie gave up Facebook, she had an epiphany: “I do want to connect socially,” she told me, “but for a bigger purpose, and with a specific group of people, and to share a valuable message.” So she started her own blog on a topic she finds important. “It’s early days yet, but I’m enjoying this redirection my time and creative energy into making something that’s uniquely me, instead of getting caught up in the ‘compete and compare’ culture of social media.”

–> David was a former professor looking for a new job after moving to a different state. Ignoring the traditional advice that social media is key to finding jobs (as I also recommend), he deleted his accounts and dedicated his newfound free time to a more traditional job search. “I started getting more and more job interviews,” he told me, attributing his success to being able to deeply research open positions. This effort culminated in the last last week of the declutter: “I had five job interviews in five days and two offers.” He also competed a full rewrite of a young adult novel he was writing. “So I would say this experiment was a wild success,” he concluded.

Analog Social Media

My initial interpretation of stories like the above was that tools like social media consume lots of time. Therefore, when you minimize their role in your life, you free up time for other, more valuable pursuits.

On closer inspection, however, I refined this take. Many of the people who sent me declutter stories were not simply replacing social media use with unrelated activities. In many cases, they were instead finding improved sources of the benefits that drew them to social media in the first place.

For example…

One reason people use social media is that browsing their accounts provides a quick hit of entertainment. As many of the participants in my declutter discovered, however, old fashioned, analog activities can provide much richer entertainment. Just ask Angie about her rediscovery of painting or James about the return of his chess hobby.

Another reason people use social media is to connect with family and friends. But many of my participants found that real world efforts to stay in touch proved more rewarding than clicking “like” or scrolling timelines. We see this, for example, in Alma spending more time with her daughters, or Bob investing energy into seriously listening to his family.

People also use social media to stay informed and learn new ideas. But a consistent theme in the declutter stories was the overall negative impact of trying to keep up with breaking news online. Ari’s experience, in which he discovered that reading a print newspaper kept him both informed and much less anxious, was shared by many participants who explored “slower” ways to keep up with the news. And when it comes to learning new ideas, perhaps the most common observation made by declutter participants was that they ended up reading many more books. Jess and Andy’s experience of rediscovering the joy of reading are just two case studies among many similar stories that I received.

In some sense, the participants in my digital declutter experiment developed analog alternatives to social media, in which they recreated many of the benefits promised by these digital tools using more intentional real world activities.

The resulting analog social media tended to prove significantly more satisfying and rewarding than the addictive experiences offered through screens by the algorithmic attention economy. It also had the advantage of freeing participants from the sense that their personhood is constantly being sliced, diced and packaged into digital bundles to be sold to the highest bidder.

Beyond Loss Aversion

In recent decades, our culture has developed a strange loss aversion when it comes to digital consumer products.

Even people who are fed up with the deprivations of the algorithmic attention economy are often reluctant to give up services like social media because doing so might lead them to lose some benefits. Loss aversion teaches them to avoid such losses at all costs.

The experiments in analog social media described above, however, highlight an alternative to this obsession with loss aversion. Instead of treating all benefits as equal, you can instead ask what activities provide the best benefits.

Facebook, for example, might help your social life. But redirecting the 50 minutes per day the average Facebook user spends using these services toward phone conversations and real world outings will likely benefit your social life much more.

To focus on the latter is not missing out on the benefits of Facebook. It’s instead replacing Facebook with an activity that boasts an even better return on investment.

To state this more abstractly:

Focusing on the most beneficial activities to the exclusion of less beneficial alternatives can leave you better off than trying to clutter your life with everything that might offer some value.

This idea is not new. It’s the foundation of all minimalism philosophies, including my own concept of digital minimalism. But I wanted to emphasize its importance in our current moment because I think it should be part of the recently energized cultural conversation surrounding social media.

When it comes to tools like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram: don’t let the fear of missing out dictate how you live your life. The most productive and fulfilled people I know often got where they are by doubling down on the activities that return them huge benefits, while happily ignoring everything else.

March 24, 2018

Beyond #DeleteFacebook: More Thoughts on Embracing the Social Internet Over Social Media

A Social Transition

Last week, I wrote a blog post emphasizing the distinction between the social internet and social media. The former describes the internet’s ability to enable connection, learning, and expression. The latter describes the attempt of a small number of large companies to monetize these capabilities inside walled-garden, monopoly platforms.

My argument is that you can embrace the social internet without having to become a “gadget” inside the algorithmic attention economy machinations of the social media conglomerates. As noted previously, I think this is the right answer for those who are fed up with the dehumanizing aspects of social media, but are reluctant to give up altogether on the potential of the internet to bring people together.

The key follow up question, of course, is how to fruitfully engage with the social internet outside the convenient confines of social media. In my last post I pointed toward one possibility: the development of open social protocols that support the network effect usefulness of large social networks without a centralized company in charge.

This solution, however, requires that you wait for others to make progress on a somewhat complicated technological agenda.

In this post, I want to discuss two additional approaches that individuals can put in place right now to begin their transition from social media to the social internet.

The first approach provides an intermediate step — a way to minimize the worst effects of social media without fully leaving its ecosystem. The second approach describes a more severe separation.

Approach #1: The Slow Social Media Philosophy

In my 2016 book, Deep Work, I proposed a strictly binary approach to social media: you should perform an honest cost/benefit analysis on the social media platforms in your life, and quit all services that don’t provide substantially more benefits than costs with respect to things you truly value.

The issue with this idea, as I discovered, is that many people could identify a small number of important benefits provided to them by particular social media platforms that couldn’t be easily replaced. Two common examples of such benefits include sharing photos of your kids with relatives on Instagram, and keeping up with important community or support organizations that coordinate using Facebook Groups.

This is problematic because once you allow one of these platforms into your life for any reason, they have a way of annexing your cognitive landscape well beyond the boundaries of your original intent.

The average user now spends almost two hours per day on social media — at best a small fraction of this time is dedicated to the “important” reasons most would list when asked why they need to use these services.

In other words: it’s not just what social media you use, but how you use it.

With this in mind, in the two years that have passed since the original publication of Deep Work, I’ve evolved a more nuanced philosophy that I call slow social media.

Here are the basic principles:

Only use a given social media service if it provides valuable benefits that would be hard to replace. Use these services only for these purposes.

Delete all social media apps from your phone. (Few serious uses for social media require that you can access it wherever you are throughout the day.) Instead, access social media through a web browser on your laptop or desktop, once or twice a week.

When logged onto a social media service, don’t click “like” or follow links unrelated to your specific, high-value purposes — these activities mainly serve the social media conglomerate’s attempts to package you into data slivers that they can sell to the highest bidder.

Practicing slow social media allows you to maintain the hard to replace value that these services might provide you, while at the same time neutering their ability to transform you into a pawn in their algorithmic attention economy games.

Adding these restrictions also has the benefit of clarifying the true value of the activities that keep you in the social media orbit. If you find that the extra obstacle of using a web browser instead of your phone prevents you from using a given service for more than a month, than you should quit it altogether.

I was surprised by how many of my readers reported exactly this experience, proving that the stories they told themselves about social media’s importance to their existence were more fictional than they had realized.

Approach #2: Own Your Own Domain

In a recent issue of The Hedgehog Review, Alan Jacobs wrote an interesting essay titled “Tending the Digital Commons.” In this piece, Jacobs highlights the dangerous tradeoff implicit in using the major social media platforms.

These services, he notes, provide you convenience (they’re easy to learn and use, and provide access to a large existing network of users), but in exchange, they maintain control over the information your produce.

They can then monetize your work in any way that suits their bottom line. As Jacobs writes, it’s incorrect to call the major social media platforms “walled gardens,” because…

“…they are not gardens; they are walled industrial sites, within which users, for no financial compensation, produce data which the owners of the factories sift and then sell.”

This is an economic state that the techno-critic Nicholas Carr provocatively describes as “digital sharecropping.”

Perhaps more pernicious than the ability of these “walled industrial sites” to exploit your labor, however, is their ability to control your behavior — nudging you toward certain ways of describing yourself and encountering the world that make you more profitable to the social media barons, but might alienate you from your humanity.

(This is the chief concern voiced by Jaron Lanier, who first warned us about these issues over twenty years ago.)

What’s the solution? Here’s Jacobs:

“We need to revivify the open Web and teach others—especially those who have never known the open Web—to learn to live extramurally: outside the walls. What do I mean by ‘the open Web’? I mean the World Wide Web as created by Tim Berners-Lee and extended by later coders.”

To be more concrete, he’s suggesting that if you want to connect and express yourself online, the best way to do so is to own your own website.

Buy a domain. Setup a web hosting account (my host, A2, has introductory packages that cost less than $4 a month). Install WordPress or hand code a web site for this account. Let people follow you directly by checking your site, or subscribing to an RSS feed or email newsletter.

In other words, acquire your own damn digital land on which you can do whatever you want without anyone else trying to exploit you or influence your behavior.

I’m biased, of course, because this is my approach to the social internet. I’ve never had a social media account. (For the record, @CalNewport is not me — it’s a fake Twitter account that I know nothing about.) Instead, I’ve built my own little empire here on calnewport.com where no one can bother me, or insert advertisements against my will, or, ahem, use my behavior to help influence political campaigns.

I can tell you from experience that this approach is harder than simply setting up a Twitter handle and letting the clever hashtags fly, but it’s immensely more satisfying to produce things when you’re not a data point in some Silicon Valley revenue report.

It’s also, however, humbling.

As I wrote in Deep Work, part of the power of the social media business model is that it introduces a type of attention collectivism, where I’ll promise to pretend to care what you have to say (by clicking “like” or leaving a quick comment), if you do the same for me. This is incredibly seductive, though ultimately hollow.

When you run your own site, reality is harsher. If people don’t truly care about what you have to say, or don’t truly care about you, they’re not going to stick around. You have to earn their attention. Which can be really, really hard.

But I don’t think that this is a bad thing.

For those who want recognition, this reality provides a useful forcing function for helping them through the deliberate work of cultivating thoughts worth sharing.

For those who don’t crave recognition, it induces a digital life that’s more localized to closer friends and family — a state that’s more congruent with our fundamental human instincts.

Conclusion

Slow social media and escaping the walled factories of industrial social media are two ways to step toward a more authentic social internet experience. They’re not, however, the only ways. As with my last post on this subject, I’m more interested in sparking new ways of thinking about your digital life than I am in providing you the definitive road map.

March 20, 2018

On Social Media and Its Discontents

Split Reactions

As someone who has publicly criticized the major social media platforms for years, I’ve become familiar with the common arguments surrounding this topic.

One of the more interesting trends I’ve observed about this conversation is the split reaction to social media I used to hear from the political left before the 2016 election scrambled everything.

This split was defined largely by age.

Younger progressives were fiercely in favor of social media and were often appalled that people like me might say something negative about these services.

I remember one particularly lively radio debate, held on the Canadian equivalent of NPR, in which one of the other guests fought my suggestion that users should perform a personal cost/benefit analysis for these tools by arguing that even discussing this strategy was problematic as it might trick people into not using social media — a self-evident tragedy.

Older progressives, by contrast, were more skeptical of these platforms. This was especially true of tech-savvy activists like Jaron Lanier or Douglas Rushkoff who were connected to earlier techno-utopian movements.

On closer analysis, this gap seemed to stem from how these different cohorts understood social media’s relationship to the internet.

Two Visions of The Internet

The young progressives grew up in a time when platform monopolies like Facebook were so dominant that they seemed inextricably intertwined into the fabric of the internet. To criticize social media, therefore, was to criticize the internet’s general ability to do useful things like connect people, spread information, and support activism and expression.

The older progressives, however, remember the internet before the platform monopolies. They were concerned to observe a small number of companies attempt to consolidate much of the internet into their for-profit, walled gardens.

To them, social media is not the internet. It was instead a force that was co-opting the internet — including the powerful capabilities listed above — in ways that would almost certainly lead to trouble. (See Tim Wu’s The Master Switch for an interesting take on this inevitable “cycle.”)

I’m introducing this split because I think the older progressives largely had it right. There’s a distinction between the social internet and social media.

The social internet describes the general ways in which the global communication network and open protocols known as “the internet” enable good things like connecting people, spreading information, and supporting expression and activism.

Social media, by contrast, describes the attempt to privatize these capabilities by large companies within the newly emerged algorithmic attention economy, a particularly virulent strain of the attention sector that leverages personal data and sophisticated algorithms to ruthlessly siphon users’ cognitive capital.

I support the social internet. I’m incredibly wary of social media.

Understanding the difference between these two statements is crucial if we’re going to make progress on the issues surrounding social media that have, during the last year, finally entered our mainstream cultural conversation.

If we fail to distinguish the social internet from social media, we’ll proceed by attempting to reform social media through better self-regulation and legislative controls — an approach I believe to be insufficient on its own.

On the other hand, if we recognize that the benefits of the social internet can exist outside the increasingly authoritarian confines of the algorithmic attention economy, we can explore attempts to replace social media with better alternatives.

In my opinion, any vision of a better future for the internet must include this latter conversation.

One Possible Solution: Social Protocols

The tricky question, of course, is how exactly one enables a useful social internet in the absence of the network effects and economic resources provided by the algorithmic attention economy.

One intriguing answer is the idea of augmenting the basic infrastructure of the internet with social protocols.

In short, these protocols would enable the following two functions:

A way for individuals to create and own a digital identity that no one else can manipulate or forge.

A way for two digital identities to agree to establish a descriptive social link in such a way that outside observers can validate that both identities did in fact agree to form that link.

There are few serious technical obstacles to implementing these protocols, which require only standard asymmetric cryptography primitives. But their impact could be significant.

As proponents of this approach have pointed out, social protocols hold the potential to revolutionize the social internet.

In more detail, these protocols could enable a version of the internet that includes a vast and descriptive social graph that’s owned by the users themselves, instead of existing in the private database of a single monopolistic company.

In this ecosystem, many different applications can leverage this distributed social graph to offer useful features to users. By eliminating the need for each such social application to create a network from scratch, a vibrant competitive marketplace can emerge.

Crucially, this marketplace could then offer useful alternatives to the increasing number of people fed up with the excesses of the algorithmic attention economy.

People like Facebook. But if you could offer them a similar alternative that stripped away the most unsavory elements of Zuckerberg’s empire (perhaps funded by a Wikipedia-style nonprofit collective, or a modest subscription fee), many would happily jump ship.

This discussion of social protocols, of course, elides many important details. For an interesting take that fills in some of this missing information, check out Steven Johnson’s recent New York Times Magazine article.*

In Conclusion

My point with this essay is not to present detailed technical proposals. I’m interested instead in providing a flavor of the types of options that emerge once we begin to realize that the social internet and social media are not the same thing, and that this reality gives us more options than we might have first imagined for improving our digital lives.

#####

* While reading the Johnson article, keep in mind that I don’t necessarily share its conviction that blockchain technology is somehow fundamental to implementing these social protocol visions. As a computer scientist who specializes in the theory of distributed systems, I’ve become increasingly wary of the arguments that lead blockchain enthusiasts to believe that “trust” requires the disintermediation of any formal organization or institution in the design of a distributed system. But this is a different conversation for a different time…

March 15, 2018

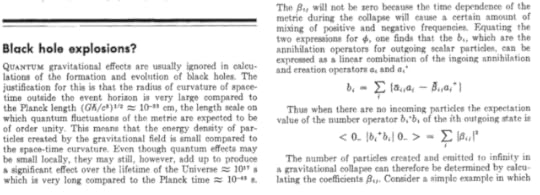

Stephen Hawking’s Radical Thinking

The Death of a Genius

Earlier this week, Stephen Hawking died. It was a sad day for lovers of science.

Hawking’s breakthrough work from 1974 provided the world a new understanding of black holes. It also unified, for the first time, quantum mechanics with gravity — laying the conceptual foundation on which any attempt at a unified theory of physics must build.

There is, however, another important insight to extract from Hawking’s efforts — one that’s less often discussed…

New Thinking

Hawking began serious work on his breakthrough calculation a decade after he was diagnosed with ALS. By this point, he was unable to read books on his own or write down equations.

As the New York Times reports in their (excellent) obituary, Hawking had friends “turn the pages of quantum theory textbooks as [he] sat motionless staring at them for months.”

Unable to write, he then attacked the problem through mental “pictures and diagrams,” seeking visual intuition (a technique also deployed by Einstein).

“People have the mistaken impression that mathematics is just equations,” he once explained. “In fact, equations are just the boring part of mathematics.”

When it came time to work out the “boring” equations for his breakthrough work, he did the whole calculation, carefully, step-by-step, in his head.

The resulting 1974 article, published in the journal Nature, was described by Hawking’s thesis adviser as “the most beautiful paper in the history of physics.”

This part of Hawking’s story is important because it underscores how little we still understand about the attention capital latent in the human brain.

Driven by the constraints of his affliction, Hawking approached his research with an inventive cognitive style that allowed him to make progress where his peers were stuck.

In doing so, he demonstrated that when it comes to feats of inventive concentration, our brains are likely capable of much more than we suspect.

#####

When I first got started in writing, as a nobody 21-year-old with a modest book contract from Random House, the NPR host and career coach/writer Marty Nemko was one of the first professionals to take me and my ideas seriously. He recently published a book of some his favorite essays. In the spirit of returning the favor, I want to bring it to your attention.

March 2, 2018

Tim Wu on the Tyranny of Convenience

An Important Essay

Earlier this month, Tim Wu wrote an important 2500-word essay for the New York Times’s Sunday Review. It was titled: “The Tyranny of Convenience.”

Wu’s piece is both deep and scattered — an indication that the target of his inquiry, the role of “convenience” in shaping the culture and economy of the last century, is both crucial and under-explored.

His thesis begins with the claim that we’ve increasingly oriented our lives around convenience, which has benefits, such as reducing drudgery, but at the same time can leech individuality and character from our lives.

This basic idea is not new. Mid-century writers like Richard Yates were already quite concerned about related issues like suburban conformity.

But Wu distinguishes his analysis by identifying how consumer-oriented companies reacted to the destabilization of the 1960’s counterculture by instead focusing on making the quest for individuality itself more convenient.

Here’s Wu:

“Most of the powerful and important technologies created over the past few decades deliver convenience in the service of personalization and individuality. Think of the VCR, the playlist, the Facebook page, the Instagram account. This kind of convenience is no longer about saving physical labor…It is about minimizing the mental resources, the mental exertion, required to choose among the options that express ourselves.”

The irony, Wu points out, is that this convenient individuality turns out to be “surprisingly homogenizing.”

As he elaborates:

“Everyone, or nearly everyone, is on Facebook, It is the most convenient way to keep track of your friends and family, who in theory should represent what is unique about you and your life. Yet Facebook seems to make us all the same.”

I think Wu’s on to something. These contradictions of convenience are crucial to understanding the dissatisfactions of our current moment.

Streaming music services like Spotify made the experience of listening to music you like easier than ever before in the history of this medium. In response, however, the cumbersome vinyl record surged in popularity.

Making music more convenient seems to have made it worse.

In the professional sector, email and smartphones makes communication with colleagues ubiquitous and trivial. In response, however, non-industrial productivity stagnated.

Making business communication more convenient seems to have made people worse at creating valuable things.

Wu concludes with an interesting suggestion: “So let’s reflect on the tyranny of convenience, try more often to resist its stupefying power, and see what happens.”

I, for one, am in favor of this experiment.

(Photo by Fabien LE JEUNE)

February 16, 2018

Sebastian Junger Never Owned a Smartphone (and Why This Matters)

Junger’s Radical Simplicity

Last November, journalist Sebastian Junger appeared on Joe Rogan’s podcast. The conversation lasted over two hours, but it was the first two minutes that caught my attention:

Joe: You have a real flip phone?

Sebastian: I do have real flip phone.

Joe: And you said you didn’t go back to it, you never left…

Sebastian: I never left her.

Joe: You never went, like, iPhone…Android…never?

Sebastian: No, I never even thought about it

…

Joe: There’s no draw at all? Using the internet, answering email?

Sebastian: Well, I have a laptop at home and I do access the internet, yes.

Joe: But when you’re out, you don’t want to mess with it?

Sebastian: No, when I’m out, I want to be out in the world. If you’re looking at your phone, you’re not in the world, so you don’t get either…I just look around at this — and I’m an anthropologist, and I’m interested in human behavior — and I look at the behavior, like literally, the physical behavior with people with smartphones and…it looks anti-social and unhappy and anxious, and I don’t want to look like that, and I don’t want to feel like how I think those people feel.

Joe: Wow, that’s deep. I’m a junkie.

In addition to being provocative, this exchange is important because it presents a cogent example of a new type of thinking I’m pleased to see gaining prominence in our cultural discussion surrounding technology.

From Materialism to Humanism

The last thirty years, in particular, have supported an ethic of techno-materialism, in which we assess the value of new technologies on the technologies’ own terms.

We need the Pentium because it’s faster than the 486. We need the latest retina display becomes the resolution is twice as sharp. We need to use Snapchat because 150 million people already do.

The problem with techno-materialism is that just because a new technology was better than the old, or did something new and interesting, didn’t mean that it made us happier.

Throughout this extended period of the Silicon Valley superhero, we kept ending up surprised to learn that faster, newer, more exciting technologies sometimes even made our lives feel worse.

In the above exchange, Sebastian Junger is implicitly promoting an alternative philosophy: techno-humanism. This philosophy* says that a new technology is only useful in so much that it makes our lives more meaningful and satisfying.

He would agree that the ability to connect with a vast network of people and information, through a high-speed digital radio link, delivered into a sliver of glass and silicon thinner than a deck of cards, is an amazing feat of technological wizardry. By the standards of techno-materialism, it’s a triumph!

But he doesn’t think these smartphones will make his human life richer. Indeed, based on his training as an anthropologist, and his recent (excellent) journalistic work on human sociality, he has reasons to fear that its net impact would be to make his less rich.

So he sticks with the flip phone. Apps be damned.

Examples of techno-humanism seem radical when first encountered, but I think more people are coming around to this philosophy’s self-evident logic.

#####

* I’m somewhat wary to use the term “techno-humanism” because it has been co-opted, to some degree, by the transhumanists, who believe that humans will increasingly merge with technology until the point that we arrive at a transcendent singularity. The techno-humanism I’m talking about here is much more grounded and much less grandiose; it’s simply about prioritizing quality human experience over the self-referential benefits of the technological.

February 8, 2018

Facebook’s Desperate Smoke Screen

Soros vs. Facebook

One of the big headlines from last month’s World Economic Forum at Davos was a scathing speech delivered by George Soros. The billionaire philanthropist and liberal activist decried what he saw as multiple threats to open society in our current moment, including the rise of authoritarian regimes in Eastern Europe, and the behavior of the Executive here at home.

Not surprisingly, what caught my attention was when Soros directed his ire toward social media.

As John Cassidy reports in the New Yorker, Soros suggested that these “tech giants”, in addition to “making excessive profits and stifling innovation,” were “causing larger social and political problems.”

Soros began with the social problems, noting that social media companies “deliberately engineer addiction to the services they provide,” acting like casinos that “have developed techniques to hook gamblers to the point where they gamble away all their money, even money they don’t have.”

He then turned to the political problems, arguing that these companies have an undue ability to influence people’s behavior by leveraging their massive data stores to precisely target messages that nudge users in specific directions.

This is nothing less, Soros claims, than a theft of citizens’ autonomy. “People without the freedom of mind can be easily manipulated.” (See Jaron Lanier’s new book for an eloquent investigation of this idea.)

The Smoke Screen

In my opinion, the first problem — the engineered addiction — is the more pressing issue surrounding social media. These services relentlessly sap time and attention from peoples’ personal and professional lives that could be directed toward more meaningful and productive pursuits, and instead package it for resale to advertisers so the value can be crystalized for a small number of major investors. (See Douglas Rushkoff for more on these economic dynamics.)

And we don’t even know yet the harm it’s causing young people, though some suggest it might be worse than we suspect.

It’s important to recognize that the public discussion of this issue is a serious problem for attention economy companies whose entire business model depends on getting people to use their services as much as possible.

Facebook’s revenue, for example, is almost entirely a function of the number of minutes the average user spends per week engaging with the service. Reducing this by even 5 to 10% — by tamping down or eliminating some of Facebook’s most addictive features — would have a disastrous impact on the quarterly earnings of this $500 billion company.

As Jeff Bercovi wrote in Inc. last month:

“[A]t Facebook, engagement is and has always been the primary success metric. For the company to move away from it onto some new standard would be a tectonic shift affecting every part of the business, from product design to ad sales.”

To ask Facebook to make their service less addictive would be like asking Exxon Mobile to switch to less efficient oil pumps: it would be a body blow to their bottom line, and investors wouldn’t tolerate it.

With all this in mind, it’s not surprising that Facebook’s reaction to the Soros speech ignored the social issues and instead focused like a laser on the significantly more tractable alternative of the political issues.

In more detail, a few days after this speech, Facebook initiated a series of posts on their company blog about Facebook’s potential to harm democracy. This series includes essays from outsiders who have been publicly critical about Facebook’s impact on the political process.

As Facebook explains: “We did this because serious discussion of these issues cannot occur without robust debate.”

Yeah right.

This move is not purely an effort to confront Facebook’s problems, it is, I suspect, in large part a desperate attempt to distract the media and public from the social issues that Facebook knows it cannot resolve without inflecting serious self-harm.

Outrage-invoking political content might have been good business for Facebook, but in its absence, this company’s attention engineers can tap into any number of other distraction wells to keep users compulsively tapping the little blue icon on their phone.

In other words, fixing Facebook’s negative impacts on democracy won’t necessarily hurt their bottom line, while admitting that their business relies on a foundation of addiction and exploitation definitely would.

It’s no surprise then that we’re hearing so much about the former and only silence on the latter.

Making Facebook good for democracy is not entirely altruistic. It is, in many ways, also a smoke screen meant to obscure the fundamental reality that this service, like many social media products, depends for its very survival on its ability to exploit its users’ time and attention.

February 1, 2018

On Simple Productivity Systems and Complex Plans

BuJoPro No More

Last month, I wrote a post about the popular bullet journal (BuJo) personal productivity system. In this article, I pontificated on a potential variation I called BuJoPro that I thought might better accomodate the demands of high intensity jobs.

BuJoPro appealed to me because it promised to unite my disparate and admittedly ad hoc systems into one elegant notebook. I liked the idea of having a single analog artifact I could carry with me and whip out, at any point, to efficiently tweak the levers that control the many moving parts of my life.

Enamored by my own hype, I then spent a couple weeks trying out this new breakthrough concept.

It was not a success.

I’ve since abandoned BuJoPro and returned to my old creaky productivity system that consists of Black n’ Red notebooks for daily plans, printouts of plain text files for weekly plans, and a collection of emails sent to myself describing temporary plans and experimental heuristics.

I learned an important lesson from this experience: there’s a difference between simplifying the complexity of your productivity systems and simplifying the complexity of your plans.

Simple Systems and Complex Plans

As I first argued way back in Straight-A, overly-complex systems create too much friction — leading you to eventually give up the system altogether. It was this legitimate bias toward simplification that attracted me to the one-notebook minimalism of bullet journal-based productivity.

The problem, however, was that my handwritten scratches on the 5 x 8 pages of my sleek dot-formatted journal couldn’t keep up with the raw amount of information needed to capture my current productivity vista, or the frequent revisions needed to keep this perspective useful.

As it turns out, my Black n’ Red notebooks work well for daily planning because they give me two full 8.5 x 11 lie-flat spiral-bounds pages to work on each day. I tend to use most of these 187 square inches to elaborate the details of my time blocks, leave room for changes, and capture tasks and notes for future consideration.

Similarly, the weekly plans I type up in plain text files require, on average, 3 – 5 single-spaced and chaotically formatted pages. It’s not unusual for me to edit and print out significantly revised versions of this plan two or three times in a given week.

And don’t even get me started on the temporary plans and heuristics lurking in my inbox. At the moment, there are six different self-authored email threads that I review each week to help keep me aimed in the right direction.

Considered altogether, the total amount of information I record, read, and regularly change to keep my energy focused productively is simply way too voluminous for me to tame with a single medium-size notebook and some fine-tipped markers.

I’m okay with this. And you should be too.

Put another way, the lesson I hope you extract from my BuJoPro experience is that it’s fine if your life is complicated, and accordingly your attempts to tame it are complicated as well.

Try to keep your systems simple, but make peace with the reality that what these systems contain might be too wild to capture on a few elegantly-formatted pages.

(Image from the official bullet journal web site.)

January 28, 2018

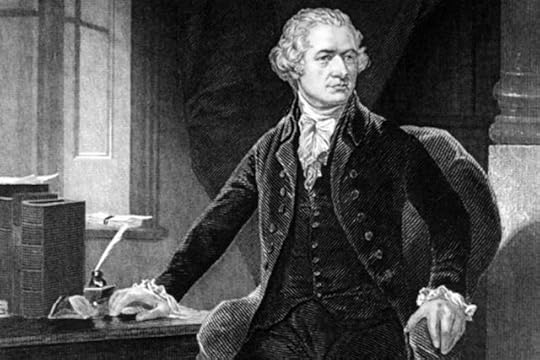

Alexander Hamilton’s Deep Advice

Deep Advice from a Founding Father

In the year 1800, Alexander Hamilton sent his son Philip the following letter, which laid out a set of rules that Philip should follow to make the most out of his legal training after his graduation from Columbia College:

Rules for Mr Philip Hamilton[:] from the first of April to the first of October he is to rise not later than six o’clock—The rest of the year not later than Seven. If Earlier he will deserve commendation. Ten will be his hour of going to bed throughout the year.

From the time he is dressed in the morning till nine o clock (the time for breakfast Excepted) he is to read Law.

At nine he goes to the office & continues there till dinner time—he will be occupied partly in the writing and partly in reading law.

After Dinner he reads law at home till five o’clock. From this hour till seven he disposes of his time as he pleases. From seven to ten he reads and studies what ever he pleases.

From twelve on Saturday he is at Liberty to amuse himself.

On Sunday he will attend the morning Church. The rest of the day may be applied to innocent recreations.

He must not Depart from any of these rules without my permission.

To our modern sensibilities, this schedule might seem overly rigorous. But Hamilton, who along with Jefferson and Madison, was one our most intellectual founder fathers, had learned through experience that doing anything worthwhile with your brain requires a foundation built on thousands of hours of deep work.

His schedule for his son was meant to trim waste and get right to the hard cognitive calisthenics needed to get Philip’s mind into shape.

Perhaps not surprisingly, I like this letter. In our current age, with its emphasis on personal branding, social network marketing, clever retweets and mobile accessibility, it’s important to remember that in many fields there’s still no substitute for hard brain work.

If you want to make a difference, you can’t avoid the necessity of waking up at six to read law before breakfast.

#####

(Hat tip: Warren S.)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers