Cal Newport's Blog, page 27

March 27, 2019

The Arizona Cardinals Now Give Their Players Phone Breaks

Photo by Skitterphoto.

Photo by Skitterphoto.Earlier this week, at the NFL owners meetings, Kliff Kingsbury, the new head coach of the Arizona Cardinals, revealed a new rule for team meetings: “cellphone breaks.”

As reported by ESPN, Kingsbury introduces these breaks every 20 – 30 minutes during team gatherings. As he explained:

“You start to see kind of hands twitching and legs shaking, and you know they need to get that social media fix, so we’ll let them hop over there and then get back in the meeting and refocus.”

Many concerned readers sent me this article, and with good reason. It’s an extreme case of a techno-philosophy that I facetiously call the kids these days mindset, in which parents, educators, bosses and (it now seems) coaches shrug their shoulders when confronted with the impacts of highly addictive technology on young people.

This football example is useful because it so clearly highlights the shortsightedness of this strategy.

(Do you know what lasts much longer than 20 – 30 minutes? NFL games. And there are no phone breaks once you’re on the field.)

Instead of accommodating his player’s twitching hands, therefore, perhaps Kingsbury should see this reaction as a crisis. Elite level sports require phenomenal concentration. Even a small epsilon degradation in this ability can be the difference between a cornerback disrupting a play or being burned on a slant, which itself can be the difference-maker in a game.

Most coaches would never tolerate a habit that was clearly harming their players’ physical fitness, regardless of how popular it was in the general public. The same standards should hold for their players’ cognitive fitness.

The broader point here, however, is that these standards should also extend to less obvious applications of this mindset, such as when a teacher concedes to student demands to replace written book reports with YouTube videos, or a parent shrugs off a child’s Fortnite addiction.

Part of growing into a meaningful and impactful adult life is developing the ability to replace what’s fun with what’s important. This process is hard, and therefore requires, for lack of a better word, some good coaching.

#####

Unrelated administrative note: My friend Scott Young, who is soon to publish a book on Ultralearning , opened his famed Rapid Learner course this week for new students. If you’re interested in high performance learning techniques for professional or personal development reasons, it’s worth a closer look .

March 20, 2019

Mike Trout Doesn’t Care About His Online Brand. He Just Made $430 Million.

Photo of Mike Trout from 2013 by Keith Allison.

Photo of Mike Trout from 2013 by Keith Allison.Mike Trout, the center fielder for the Los Angeles Angels, is finalizing a $430 million contract extension with his team. This is the largest deal in the history of professional sports.

One of the surprising elements of Trout’s story is that he’s reached these unprecedented heights while remaining, to quote Tom Boswell from today’s Washington Post, “a quiet, understated player, who has never tried to brand himself.”

I got in some hot water a few years ago for writing a New York Times op-ed in which I argued that young people needed to spend less energy desperately trying to build their online presence, and more energy quietly developing unambiguously valuable skills. (I even wrote a book about this.)

Trout represents this philosophy pushed to an extreme. When you average 9.0 WAR over six seasons, you don’t have to worry about your Instagram followers.

Trout’s talent, of course, approaches mythological levels, which made his commitment to fundamentals a safe bet. But as with any good myth, it conveys a deeper truth. In almost any professional endeavor, developing unambiguously rare and valuable skills trumps an amorphous commitment to cultivating followers or strengthening an online brand (with a small number of well-publicized exceptions).

It also helps if you can turn on a major league fastball thrown down and in.

March 15, 2019

Digital Minimalism and Ancestral Health (Or, Would Grok Tweet?)

The ancestral health movement argues that over long periods of time, evolution adapts species to their environments. It follows that when it comes to human well-being, we should pay attention to how we ate and behaved throughout the vast majority of our evolutionary history.

Like most lifestyle movements, ancestral health has spawned its share of hucksters and extremists, but the underlying logic seems self-evident, and the success stories can be compelling.

After recent appearances on Paleo Magazine Radio and Mark Hyman’s podcast, and my embrace of Mark Sisson’s advice to help stay lean and energized on book tour, I’ve begun to think more about the natural intersection of digital minimalism and ancestral health.

Consider these points, all of which I provide detailed arguments for in Digital Minimalism:

Humans have evolved to build strong social connections with family, close friends, and community through face-to-face interactions that require non-trivial sacrifices of time and energy. (For more on this, see Chapter 5, or the book Social .)The human brain requires regular periods of “solitude” in which it is alone with its own thoughts and observing the world around it. (For more on this, see Chapter 4, or the book Lead Yourself First .)Humans have a strong drive to see their intentions manifested concretely in the world, be it shaping a spear, starting a fire, or bending electrical conduit into an efficient pattern. (For more on this, see Chapter 6, or the book Shop Class as Soulcraft .)

A side effect of our current techno-culture is that it radically diminishes these ancestral drive in our daily lives.

Social media, for example, reduces our sociality to low-friction online likes and comments, which provide a simulacrum of connection, but are barely recognized by our primal brain as socializing at all — leaving us paradoxically lonelier.

Algorithmically-optimized distraction delivered through a ubiquitous screen provides a pleasant escape in the moment from the difficulties of our lives, but it also banishes every last vestige of solitude, throwing our brains into a shocked state of low grade anxiety.

As we become used to these spoon-fed digital trinkets, we also become less likely to put up with the friction involved in high quality leisure activities, like coercing your fingers to cleanly place a guitar chord — stymying our brains instinct to shape things with our hands.

Which is to all say that it’s becoming increasingly clear to me that if you’re serious about ancestral health, you should be as concerned about your iPhone and Instagram as you are about grain and sugar, as the former are equally as foreign to our evolutionary adaptations.

To live like Grok in our modern world, in other words, probably requires a minimalist’s skepticism toward new technology.

March 11, 2019

On Heidegger and Email

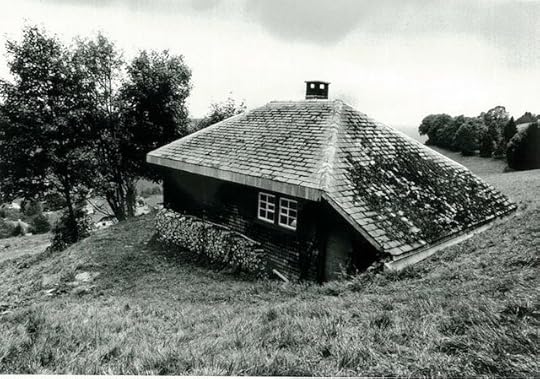

The hut near the edge of the Black Forest where Martin Heidegger developed his philosophy of Being.

The hut near the edge of the Black Forest where Martin Heidegger developed his philosophy of Being.I was in California last week promoting Digital Minimalism. One of the books I brought to keep me company was Sarah Bakewell’s insightful, and surprisingly entertaining, At The Existentialist Cafe.

In the third chapter, I came across a nice piece of focus porn concerning the philosopher Martin Heidegger.

During Heidegger’s first academic appointment, which was at the University of Marburg, his wife Elfride used an inheritance to buy some land near the Black Forest town of Todtnauberg. The plot overlooked “the grand horseshoe sweep of village and valley.”

As Bakewell elaborates:

“[Elfride] designed a wood-shingled hut to be built on the site, wedged into the hillside…Heidegger spent much time working there alone. The landscape criss-crossed by paths to help him think…in evenings or out of season it was silent and tranquil…when alone there, Heidegger would ski, walk, light a fire, cook simple meals, talk to the peasant neighbors, and settle for long hours at his desk, where…his writing took on the calm rhythm of a man chopping wood in a forest.”

Heidegger, of course, went on to become a controversial figure due to his later involvement with the Nazi party, but it’s hard to overstate the intellectual impact of his book Being and Time, which was written during this Marburg period, and helped shatter the rapidly ossifying structures of German phenomenology, ushering in a torrent of philosophical innovation.

In my more pessimistic moments of techno-contemplation, I worry about how many similarly deep thinkers we’ve accidentally “innovated” out of existed in recent years.

The metaphoric exemplar of Heidegger’s long days of writing in his Todtnauberg hut seems increasingly foreign in a world where academic life has been diminished toward the managerial by email, and social media increasingly tempts the rare egos large enough to produce something like Being and Time to pursue the immediate gratification of a righteous tweet over the tedious slog of writing an epochal book.

And yet, something about Heidegger’s purified intellectual life still appeals to us despite all these distractions. Electronic busyness offers fleeting satisfactions, but embedded in our cultural DNA is an appreciation of the deep ideas that last even after the servers power down.

Twitter is fun, but most of us would still rather our biggest minds quietly wander the paths surrounding their Black Forest hideaways, hunting transformation over retweets. We can hope that as long as this instinct persists, a correction to our current slide toward shallowness remains inevitable.

March 1, 2019

Digital Minimalism for Parents

One of the more interesting things about being on the road promoting Digital Minimalism is encountering readers and learning how they’re making use of these ideas.

One such group that’s particularly interesting to me is digital minimalist parents. I’m a parent, but the oldest of my three boys is only six, so I haven’t yet directly grappled with the serious issues surrounding kids in an age of smartphones, making me eager to hear from those who are waging this battle now.

As I’ve talked with more of these parents, a consistent reality has emerged:

Smartphones and social media are a major problem for adolescents. To ignore it with a “kids these days” shoulder shrug is becoming increasingly unacceptable. (For more on this, see my somewhat infamous interview with GQ where I speculatively compare teenage smartphone use to teenage smoking.) Any successful attempt to instill in your kids a healthier relationship with technology has to start with modeling this relationship in your own life.

This latter point is one that we parents sometimes don’t want to hear, but it keeps coming up in my conversations: if you carry your phone with you at all times, checking it constantly, it’s difficult to convince your kids not to do the same, no matter how many rules you set or warnings you deliver.

In my book, I give some cases studies of this parental modeling pushed to an extreme:

A father named Adam, for example, used his smartphone constantly at home, largely for professional reasons (his business relies on SMS for a lot of internal communication). He began to worry, however, about the example this set for his daughter as she approached adolescence, so he made a radical decision: he got rid of his smartphone.A mom named Laura made a similar decision. She has refused to ever buy a smartphone because quality social interaction with her kid, as well as her family and close friends, are a top priority, and she worried the addictive allure of an iPhone screen would distract her from the moments that mattered most.

As you might expect, these decisions were inconvenient. Adam complained to me at the time about the difficulty of trying to tap out a text message on a 9-digit flip phone keypad. Laura talked about printing out maps before going somewhere new as she doesn’t have an app to navigate her.

But I was also struck by how little Adam and Laura cared about these inconveniences. This makes sense in this context as basically everything parents do on behalf of their kids is inconvenient. I think if you look up “inconvenient” in the dictionary, there’s a picture of a sleep-deprived parent making a school lunch.

What animated them more was the idea that they were doing something intentional to make their kids’ lives better.

Most digital minimalist parents I’ve talked with recently haven’t gone so far as to give up their smartphones, but they share the same serious interest in reshaping their digital lives — even if it’s a pain — to provide a better model for their kids.

One interesting strategy I encountered, for example, is the so-called foyer phone method. In the evening, after work, you leave your phone in the foyer by the front door with your keys and wallet. If you need to look something up, you go to the foyer to use the phone. If you’re expecting a call or text message that you need to answer, you put on the ringer, and if it rings, you go to the foyer. If you’re bored during a commercial while watching TV, then you’re just bored.

It seems like a simple hack, but the result is that your interactions with your family become screen-free by default. You also avoid the micro-glances at your device as you go about your household business — glances you think are surreptitious, but that your kids are almost certainly taking note of and internalizing as a model of the phone’s importance. With this method, the smartphone becomes a tool that you deploy for specific uses, not a constant companion.

Another minimalist parenting strategy that caught my attention is making a strong commitment to analog social media — that is, real world social activities, like having friends over on a regular basis, visiting with neighbors, hosting community or religious groups at your house.

This demonstrates to kids through example the deep value of real world relationships, an important message for a generation that has attempted to relocate their entire social existence into the low-friction world of Snapchat likes and text messages. (c.f., Sherry Turkle’s excellent book on this topic).

A few weeks ago, Adam came to one of my book launch events in New York. He brought his daughter. The pride on his face underscored an important point: For most people, the embrace of digital minimalism is about improving the quality of your own life, but for parents, as I’ve been learning, it can be about something much deeper.

February 19, 2019

On Sam Harris and Stephen Fry’s Meditation Debate

Photo by Sam Harris.

Photo by Sam Harris.A few weeks ago, on his podcast, Sam Harris interviewed the actor and comedian Stephen Fry. Early in the episode, the conversation took a long detour into the topic of mindfulness meditation.

Harris, of course, is a longtime proponent of this practice. He discusses it at length in his book, Waking Up, and now offers an app to help new adherents train the skill (I’ve heard it’s good).

What sparked the diversion in the first place is when, early in the conversation, Fry expressed skepticism about meditation. Roughly speaking, his argument was the following:

Typically when we find ourselves in a chronic state of ill health it’s because we’ve moved away from something natural that our bodies have evolved to expect.Paleolithic man didn’t need gyms and diets because he naturally exercised and didn’t have access to an overabundance of bad food.Mindfulness mediation, by contrast, doesn’t seem to be replicating something natural that we’ve lost, but is instead itself a relatively contrived and complicated activity.

Harris’s response was to compare meditation to reading. They’re both complicated (read: unnatural) activities, to be sure, but they’re both really important in helping our species thrive.

Fry, who is currently using and enjoying Harris’s meditation app, conceded, and the discussion shifted toward a new direction.

I wonder, however, whether Fry should have persisted. Rousseauian romanticism aside, there’s an important application of evolutionary psychology undergirding his instinctual concern.

For one thing, the reading analogy is tenuous. Reading is a technology that radically accelerated cultural evolution — a tool that helped us achieve new goals.

Meditation, by contrast, is more palliative than instrumental, especially in its modern secular applications. It’s meant to soothe mental dis-ease, not to unlock accomplishment previously unobtainable to our species.

This motivates the question of why we need this soothing in the first place. It’s unlikely that our paleolithic ancestors existed in a state of persistent anxiety and stress, so the negative sensations we use meditation to reduce must have a more modern origin.

This is the point I think Stephen Fry was orbiting with his skepticism.

He wasn’t arguing that mindful meditation doesn’t work, as the evidence suggests that it is really quite effective, which is why I think the work Sam Harris (and Jon Kabat-Zinn before him) are doing in promoting this practice to a wider audience is vital and important.

Fry was instead correctly noting that meditation is an unnatural solution to a modern problem. Meditation helps, but it doesn’t solve the underlying issues .

What, Fry seems to be asking, is the cognitive equivalent of the natural behaviors like exercising and healthy eating that our species used to enjoy but are now missing in modern life?

I’m not the first to ask this question, and many people have proposed compelling answers (see, for example, Mark Sisson and John J. Ratey).

But something that became increasingly clear to me as I was researching Digital Minimalism, and the reason why I’m bringing up this topic in the first place, is that in recent years, our relationship with our screens has almost certainly exasperated this modern separation from a more natural way of living .

A big part of waking up, in other words, should probably involve powering down.

#####

Speaking of Digital Minimalism, I want to share a few housekeeping notes. First, I’m happy to report that the book debuted as a New York Times , Wall Street Journal , Publisher Weekly , and USA Today bestseller — so thank you all for your support.

On the same topic: if you pre-ordered the book, but forgot to fill out the form to receive the promised bonuses, send an email to digitalminimalism@penguinrandomhouse.com and we will help get you squared away.

February 7, 2019

Minimalism Grows…

Me speaking about Digital Minimalism at Company HQ in New York City on Monday Night.

Me speaking about Digital Minimalism at Company HQ in New York City on Monday Night.I only rarely write administrative posts, but because this is the launch week for my new book, I figured I’m due a break on this rule. With this in mind, I want to share a few more interesting pieces of news coverage on Digital Minimalism.

Before I do, two quick notes:

First, if you live in the Washington, DC area, come see me at Politics & Prose at 3:30 on Saturday . I’ll be taking questions and signing books.Second, if you’re pretty sure you’re going to buy the book, but haven’t yet, I want to nudge you to do so soon . (For various technical reasons, sales made before Saturday night are very useful from a bestseller list perspective. Okay, last time I’ll mention that…)

On to the publicity updates:

Amazon’s editors named Digital Minimalism one of the 10 best nonfiction books of the month, USA Today included it in its roundup of “5 books not to miss” this month, and Time called it one of the 15 New Books to Read This February.Earlier today, I was interviewed on the popular NPR show Here & Now and appeared live on Tech News Weekly .Written interviews with me also appeared in USA Today, Fatherly, and Ryan Holiday’s Daily Stoic newsletter.If you’re interested in book excerpts, you can find them at both NPR and TED.On the podcast front, more episodes with me are beginning to trickle out (with more to come), including: Mark Hyman’s podcast, The Art of Manliness, The Accidental Creative, Productivityst, Tropical MBA, The Buyer’s Mind, Curious Minds, and OPTIMIZE with Brian Johnson.

Many of you have been asking me to create a running list of all of my podcast appearances, interviews, and articles. We’re working on it, stay tuned…

February 1, 2019

The Beginning of a Digital Revolution?

It’s hard for me to believe that we’re finally here, but my new book, Digital Minimalism, comes out on Tuesday.

The early buzz about the book has exceeded my expectations, which helps validate a trend that I’ve been noticing over the past year or so: people seem like they’re finally ready to consider serious changes to their relationship with digital tools.

To help get you as excited as I am, I’ve included below a sampling of some of the early press on the book.

(Also remember, as I detailed last week, if you pre-order a copy by Tuesday, you get some immediate bonuses, and if you pre-order a second copy, you get access to a private Q&A group. More details here…)

Digital Minimalism Buzz

Steve Jobs Never Wanted Us To Use Our Smartphone Like This. (the New York Times). This is my op-ed from last week’s New York Times. It became their most emailed article of the weekend. It’s Not Too Late to Quit Social Media. (the Wall Street Journal). I was the Weekend Interview in last Saturday’s Wall Street Journal. Cal Newport on Why We’ll Look Back on Smartphones Like Cigarettes (GQ). A wide-ranging interview with GQ’s Clay Skipper. The marketing team at my publisher told me that this continues to create a stir on social media (ironically). How to Be a Digital Minimalist — The Rules (The Times of London). A sharp piece in The Times of London. Calls my new book an: “eloquent, powerful wail of despair against the ‘attention merchants’, but also an enjoyably practical guide to cutting back on screen time.” Cal Newport Has an Answer for Digital Burnout (The Ezra Klein Show). My recent interview on the new book with Ezra Klein. For those eager for more podcast content from me, worry not, I am doing a lot of podcast interviews that will begin releasing next week. How Behavioral Economics Helped Kick my Phone Addiction (The Financial Times). Writing in the Financial Times, Tim Hartford details his experience implementing the digital declutter recommended in my book.In addition: Ryan Holiday included the book on his recent list of the 15 books you need to read in 2019, Melissa Muller called it the “beginning of a digital revolution,” and it was featured in WIRED, Boing Boing and Mike Allen’s Axios AM Newsletter.

The above is just the pre-publication coverage, with a lot more on the way. Stay tuned…

January 28, 2019

Adam Savage and the IRL Digital Revolution

Myth Confirmed

I recently started re-watching old Mythbusters episodes with my two oldest boys — and we’re having a blast.

The original series, which ran on the Discovery Channel from 2006 to 2016, was hosted by special effects engineers Jamie Hyneman and Adam Savage. Curious about what happened to Jamie and Adam after the series ended, I did a little poking around and discovered that among many other things, Adam became involved in the maker website Tested.com, which was rebranded as “Adam Savage’s Tested.”

This site hosts videos which are primarily a mix of high tech product reviews and instructions for maker projects. My oldest son and I, for example, got a kick out of watching a tutorial where Adam modified an off-the-shelf Nerf gun into a 1000-shot blaster (see above).

The reason I’m bringing this up is because I’ve recently begun reading the questions submitted by members of the Digital Minimalist Book Club.

An issue that arises frequently in these queries is the ambiguous tension between the digital and the analog. I’ve been writing recently about the damage caused when low quality digital distraction push more meaningful and satisfying analog activities out of your life.

As I detail in Digital Minimalism, for example, one of the most commonly reported experiences from last year’s 1,600 person digital declutter experiment was the surprising joy of rediscovering leisure activities that used to be unexceptional, like reading random library books, knitting, or building something with your hands. Participants were often shocked to realize the degree to which these simple but fulfilling pasttimes had been push aside by mindless streaming and outraged commenting.

These observations seems to pit the analog against the digital. So how, then, do we think about Adam Savage’s Tested?

My conclusion: with great appreciation.

The goal of Tested.com is to connect maker geeks to the type of esoteric information that enables them to return to their real world shops and build a pretty damn good replica of the snub-nosed blaster from Blade Runner.

It’s a digital boost to the quality of their analog life.

More generally, there any number of similar sites, apps and gadgets out there that do a great job of taking things you already really value in the real world (IRL) and then helping you do them much better.

To a digital minimalist, this is the main point of the internet: to make life better, not to take it over.

When people accuse us of being luddites because we’re not interested in yelling at people on Twitter, they’re missing the point.

We don’t dislike digital, but our definition of success for these new technologies is not maximizing likes, it’s instead increasing the frequency with which we can replicate the smile on Adam Savage’s face when he lets loose with his custom-built 1000-shot Nerf blaster.

January 12, 2019

Why You Should Pre-Order Digital Minimalism

A copy of my new book, hot off the presses, on the custom-built minimalist library table I use to find focus in an otherwise noisy world.

A copy of my new book, hot off the presses, on the custom-built minimalist library table I use to find focus in an otherwise noisy world.My new book, Digital Minimalism, which comes out on February 5th, is available for pre-order.

If you live in the US, you can pre-order from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or a local bookstore (as well as many other retailers).

If you live in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, India or Africa, you can pre-order the UK edition at Amazon UK. (The book is also being translated into over a dozen different languages, but these will come later.)

For multiple reasons, pre-orders are much more useful than normal sales, so if you were already thinking about buying my new book, I want to humbly nudge toward considering a pre-order, and if you already pre-ordered, I want to underscore my gratitude.

To demonstrate my sincere thanks to those who take the time to help my book in this manner, I’ve put together the following incentive packages:

If you pre-order 1 copy of the book before February 5th, you’ll receive:

A video tutorial, narrated by me, that provides an inside look at the specific productivity systems I use to organize my work week. A standalone guide to the Digital Declutter process (as featured in the New York Times and detailed in my book) that I recommend for transitioning into a digital minimalist lifestyle.A 40% discount code for the Freedom internet blocking software profiled in the book. Claim your 1 copy bonuses here…

If you pre-order 2+ copies of the book (one for you and one for a friend) before February 5th, you’ll receive:

All of the above bonuses.Access to the private Digital Minimalist Book Club. For one month after the book releases in February, I’ll be be posting a weekly private video for book club members where I answer their questions about the book (or any related topics), submitted through a special email address provided only to book club members. Claim your 2+ copy bonuses here…

TO ACCESS THE BONUSES:

Pre-order Digital Minimalism from any retailer and in any format. If you have already pre-ordered (thank you!), you just need to find your invoice number from the digital receipt.Fill out THIS FORM with your invoice number(s) and contact details. (Note: If you ordered 2+ copies using multiple different orders, that’s no problem: the form can accept multiple invoice numbers.)Gain immediate access to the bonuses. Once you’ve filled out the above form, links for downloading the bonuses will appear on the form’s confirmation page. For those of you who order 2+ copies, you’ll also be provided the special email address for submitting questions for the book club. The instructions for how to access the book club videos will then be emailed to you in February.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers