Cal Newport's Blog, page 24

December 5, 2019

The Advice I Gave My Students

Toward the end of class today, one of my students asked me what advice inspired by my books I’d give them as they headed into the university’s final exam period.

I thought about it for a second before recommending a simple hack that I’ve been experimenting with recently and finding useful:

Use your smartphone only for the following activities: calls, text messages, maps, and audio (songs/podcasts/books).

I suggested that my students try this for one week while studying for their exams. I further suggested that they actually record on a calendar or in a journal whether or not they succeeded in following the rule 100% for the day. One slip to check social media, or glance at email, or look up a website, and they don’t get to mark the day as a success.

They can still do all of these online activities, but only on their laptop. When they’re away from their computer, their phone is still useful for basic operations, but it ceases to act as a crutch that helps them avoid the world around them.

This hack is lightweight — far less aggressive than what I recommend in Digital Minimalism, and therefore easier to convince people to try.

But if you give it a chance, it’s still disruptive enough to your normal routines to provide key insight into just how dependent you may have become on mediating your experience through a constant background hum of digital intervention.

December 1, 2019

How Social Media Hacked Civic Conversation

The most recent issue of The Atlantic includes a fascinating article by Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell. It’s titled, “The Dark Psychology of Social Networks.”

In Digital Minimalism, I argued that our relationship with social media was transformed when the major platforms updated their designs to make these services less about checking on other peoples’ status, and more about checking incoming “social approval indicators,” which arrive in the form of likes, retweets, shares, hearts, streaks and tags.

This key shift, which took place between 2009 and 2012, is largely responsible for retraining us to think about social media as something to check all the time. Our current moment, in which we both accept and lament the status of our phones as constant companions, was a direct consequence of these tweaks to social media technology.

(For more on this idea, see also my New York Times op-ed on Steve Jobs’s original vision for the iPhone.)

In their new article, Haidt and Rose-Stockwell trace another unintended consequence of the introduction of social approval indicators to social media: the breakdown of online civility.

Drawing from the work of philosophers Justin Tosi and Brandon Warmke, the authors argue that adding quantifiable approval to a public forum leads to what’s known as moral grandstanding, an activity in which speakers take turns, each trying to out do those who came before them in whipping up approval from the crowd:

“Grandstanders tend to ‘trump up moral charges, pile on in cases of public shaming, announce that anyone who disagrees with them is obviously wrong, or exaggerate emotional displays.’ Nuance and truth are casualties in this competition to gain the approval of the audience. Grandstanders scrutinize every word spoken by their opponents—and sometimes even their friends—for the potential to evoke public outrage. Context collapses. The speaker’s intent is ignored.”

This definitely sounds familiar.

As Haidt and Rose-Stockwell point out, this grandstanding isn’t somehow fundamental to our times, or an unavoidable side effect of public conversation, or even a necessary tactic for aggressive advocacy. It is instead an unexpected consequence of a small number of design choices made by the major social media companies a decade earlier.

These companies added easy ways to share and approve of posts to improve the experience of timeline-style content consumption, a new concept at the time. They ended up accidentally short-circuiting our brains.

The one place where I diverge from Haidt and Rose-Stockwell, however, is when it comes to solutions. At the end of their Atlantic article they offer three fixes to this current state of affairs. All of them focus on changes to existing social media platforms that would minimize the conditions that spark moral grandstanding.

What was missing from their list is an even more powerful solution that can actually create real improvement right now: encourage people to use social media much less.

The problem with Haidt and Rose-Stockwell’s suggested solutions is that they would require social media companies to make changes that would almost certainly reduce their revenue. For those who barter in attention, moral grandstanding is good business

My solution, on the other hand, can be put into action immediately and yield significantly positive results, as it has for the increasing number of people embracing a more minimalist approach to these tools.

The sooner those who write about social media accept that the current importance of these technologies are inflated, and that for most people these platforms don’t need to play a major role in their civic or personal lives, the sooner we can get about repairing the damage that we’re only now beginning to fully understand.

#####

Photo by Kheel Center.

November 24, 2019

Reflections on the Disconnected Life

Not long ago, an Australian media professor named Robert Hassan boarded the CGM CMA Rossini, a container ship, at a dock in Melbourne. He had arranged to stay on the ship for its five week passage to Singapore. He brought a handful of books, but no phone, no computer, no digital media at all. The crew didn’t speak English either, so it would largely just be Hassan alone with his own thoughts on the sea.

This solitude was, of course, the point. He was conducting an experiment on himself as part of the research for his book, Uncontained, published by an Australian university press last June. What he discovered was poignant.

After reading through his small book supply too quickly, he was faced with endless hours with nothing concrete to do, and soon found his relationship with the world around him began to change.

First, there was his memory.

“I began to think about my own history and my life and things that have happened and to begin to explore those memories [and] think about what was around them, what was behind them,” he told an interviewer on an Australian radio program. “And I began to make discoveries.”

New details emerged. A particular t-shirt someone was wearing, the jokes told, the specific sound of the laughter.

“It is amazing to think that [these details are in] there, in all of us, mostly undisturbed unless we devote the time to concentrate and go looking.”

Then there was his relationship to the world around him on the ship.

He contemplated a screwdriver mark on a hinge. “He or she was standing exactly where I am now, like a ghostly presence who leaves a permanent trace,” he remarked about the phantom source of the mark.

Dust became a preoccupation.

“It’s the stuff that literally falls away from us and our things, traces we don’t even realize we leave.”

He took apart a chair just so he could rebuild it. He became an expert observer of the sea surrounding the ship. (For more on the deep pleasures of observation, there’s no finer source than my favorite minimalist manifesto: Walden.)

Finally, his sleep changed. Operating on an unconstrained schedule, Hassan fell into a biphasal pattern, in which you sleep for a while, wake up and do some activity, and then go to sleep for a while longer.

(Such patterns were common in earlier eras. I remember reading about American colonists who talked about “first and second sleep,” and would be up writing letters, or visiting neighbors, in the middle-of-the-night hours between the two sessions.)

“I woke up and didn’t feel that I had to try and get back to sleep or feel the stress of needing to sleep. I was relaxed about sleep,” he recalls.

Hassan’s experiment (by design) was extreme. But it implies some troubling questions about our current, artificial, digitally-mediated lifestyles.

The screens we carry with us as constant companions don’t amplify or support our natural ways of being, they instead push us into an entirely new mode of existence.

This is not de facto bad; our understanding of the naturalistic fallacy leads us to distrust the assumption that the evolutionary factory presets are always necessarily best. But it would be wildly optimistic to hope that these new behaviors, which are largely driven by the profit motives of attention economy monopolies and device manufacturing giants, would just coincidently happen to also make our lives richer.

Which brings us back to digital minimalism. Most of us don’t have the ability to drop everything for a disconnected life at sea. But we do have the ability to deploy careful experiments and reflection to figure out what we really value, and then — and only then — work backwards to figure out how best to deploy technology to support these aspirations.

Perhaps the most telling clue that there’s somethings off about our current configuration, is that after his five weeks of self-imposed solitary confinement Hassan landed on a simple conclusion.

He’d do it again if he could.

(Photo by Simon Matzinger.)

November 18, 2019

The Danger of Exaggerating the Political Importance of Social Media

Photo by Matthew G.

Photo by Matthew G.The Pew Research Center recently released a new study on American Twitter use. As Jennifer Rubin reported in the Washington Post, one of the most striking findings from the report is that only 2.2% of the population currently produces 97% of political tweets.

As Rubin notes, these findings run counter to the core belief held in media and political circles that these services play a critical role in our democracy. She describes the fact that campaigns and reporters take Twitter so seriously as “bonkers.”

I noticed something similar during my book tour for Digital Minimalism. Most of the readers I met didn’t use social media for political reasons and wouldn’t describe this technology as playing an important role in their civic life. Accordingly, most of these readers didn’t care much about what content was spreading on social media, or even which data were used to target this information.

What they did care about was how much time they were spending staring at their phones. There was a widespread sense that these services had become so distracting that they were starting to take time away from activities that were clearly more important, diminishing the quality of their lives.

There exists, in other words, a gap between media/political types and normal users when it comes to understanding the role of social media in political life. The former see this technology as being inextricably intertwined in the fabric of our democracy, while the latter see it more as a distraction run amok.

I used to just find this gap curious. I’ve come to believe that it’s actually quite serious.

When you’re convinced that social media is essential, you tend to accept that it’s up to the political system to ensure that this public good properly serves the public (much in the same way we trust regulators to ensure our water is safe to drink).

The problem with this frame is that it diminishes the autonomy of individual users. While they sit around hoping that the system keeps social media behaving properly, they continue to suffer from the much more prevalent problem: overuse taking them away from more important activities.

If we instead acknowledge that for many people social media is much more superfluous, we empower users to start pushing back, making aggressive changes in their life right away — leading to immediate improvement in many aspects of their daily experience.

This is not to say that social media plays no role in political life, or that there’s no role for the political system to help monitor how these services do things like collect data or target content, but it’s counterproductive to pretend that this is the whole story.

I have no doubt that for those who work in journalism or politics, or for those who depend on YouTube viewership for cultural relevance, that social media really is at the center of their participation in public life. But for most users, it’s not. If we keep ignoring this reality, we’ll unnecessarily impede our culture’s ability to improve our relationship with these tools.

November 15, 2019

A Subtle Mistake About How to Acquire Useful Career Skills

As promised, here is the second post written by Scott Young about lessons learned from the many years we’ve run our Top Performer online course, which we’re re-opening next week. This post is about a mistake we made with our curriculum in the early pilots of the course.

If you’re missing Cal content this week, fear not, I’ll be back to my regularly-scheduled programming next week. In the meantime, you can take a look at my recent New York Times op-ed on 5-hour work days. My basic thesis: it’s hugely surprising that we don’t have many more knowledge work organizations aggressively experimenting with novel approaches to work.

######

In our early Top Performer pilots (before we even called the course “Top Performer”), Cal and I made a subtle mistake about the process we taught for acquiring career skills. It’s one I’ve seen many people make when thinking about improving their career, so I think it’s worth exploring here in case you might be making it too.

A big part of our course is executing a skill-building project. The goal is to cultivate rare and valuable skills which form the foundation for a successful career.

What we hadn’t recognized in early iterations of our course is that there are actually two different ways to go about these project, one of which tends to be much more effective.

The Difficulty with Drilling Down

The first way you can design a project to upgrade your career skills is to drill down on some aspect of your work that’s important to your job. One of our students, for example, was an academic philosopher who decided to get better at logic. Another student was an architect who decided to deepen his understanding of design.

On the surface, these kinds of projects sound like they should be helpful. Indeed, the entire idea of deliberate practice, on which our course is based, seems reflected in these projects—pick an aspect of your work, and then design an effort to focus on improving it deliberately. So what’s the problem?

The problem is that a lot of these projects didn’t generate spectacular results. Sure, the person might have felt good about deepening a skill, but these were rarely the projects that resulted in promotions, raises or transformations of a person’s work.

True, there were some exceptions. One person decided to dig deep on their understanding of a programming language, and later translated that into landing his dream job.

But even then, this particular success didn’t come from improving a skill alone. In his particular case, the student got the job because his practice activity (making online quizzes about the language he specialized in) brought him to the attention of experts in his field. Had those quizzes not been published (or acknowledged) and it’s unclear how big an impact his project would have had.

Benchmarking Success

A different style of project, however, does seem to work better: benchmark projects.

Benchmark projects are also about improving skills. However, instead of picking a skill and just trying to get better at it, you first pick a clear benchmark accomplishment that defines success. Examples of successful benchmark projects could be:

Writing: Creating a blog and producing 100 articles.Programming: Designing a useful open source library. Academia: Producing a paper that attracts multiple citations. Entrepreneurship: Creating a new product that will sells a certain amount.

Why are these projects (often) more successful than projects which are strictly about drilling a particular skill?

My experience tells me that there are two distinct advantages at play here. The first is that by tying your project to a benchmark, you can’t avoid the uncomfortable work. A deliberate practice project that’s disconnected from real-world results can unintentionally be steered away from hard efforts that move the needle, allowing you instead to wallow in that pleasing state of “tractable hardness” — a state that feels good, but generates minimum growth.

Second, benchmark projects produce a recognizable achievement at the end. This helps by allowing you to point at something concrete when trying to articulate your newly acquired skill. Good work alone can propel you forward, but making your skills more legible to outsiders is often a key part of translating those skills into actual career benefits.

How You Can Create Benchmark Projects to Grow Your Career

The way I like to think of benchmark projects is to pick something that I can’t do right now, but I might be able to do, if I improved my skills and worked at it.

These projects tend to work better when the benchmark itself

suggests what kind of efforts you might take to improve. Improving as a writer,

for instance, it would be better for me to pick a project like, “Get published

in a national newspaper or magazine” rather than “Sell one million books,”

since the former will suggest a lot of specific actions I need to take to get

my writing to the level where I could be published in a prestigious place, but

the latter doesn’t really suggest anything concrete.

Good benchmark projects are often scarier than drill-down projects. “Getting better at research” is a lot more comfortable a goal to set than, “Get my work published in a Top-5 journal.” Yet that uncomfortableness also encourages you to take a hard look at your own work.

What are some benchmarks you could strive to attain in your own work? How would those look different than attempts you’ve made in the past to simply “get better” at your work?

November 11, 2019

The Obvious Way to Improve Your Career (That Might Not Be So Obvious)

Below is a guest post from my good friend Scott Young. (Which reminds me: thank you to everyone who came to see Scott and me speak live at Solid State Books in DC last Saturday: we had a great time!) In preparation for us opening back up our Top Performer course next week, Scott’s been trying to open the curtain, so to speak, and capture in article form some of the biggest ideas we’ve learned over the years running this course.

Take it away, Scott…

#####

Sometimes the obvious advice you need to hear isn’t obvious to you. Here’s an example of this that happened just last week.

A guy on Twitter asked me if I did coaching. He felt stuck in his career and wanted to pay me to give him advice. I don’t do individual coaching (at least for money) but, I was curious so I asked him to send me some details of his situation to see if I could help.

Here were his tweets:

What do you think his mistake was?

In my mind, the biggest mistake he made was simply that he was asking me what to do next. I’m not a singer, and I don’t even work in the music industry.

So, lacking specifics, I gave the advice that was obvious to me: you need to locate people who are 2-3 steps ahead of you in the kind of career you want to have. You need to talk to these people, not just random people on the internet you admire, to map out how your career actually works.

His response:

This seems obvious in retrospect, but it actually happens a lot.

In early pilots for our course, Top Performer, Cal and I had students work through an exercise of interviewing someone in their field for career advice. One person decided he wanted to pick Tim Ferriss, even though he was working an engineering job.

The problem is that Tim Ferriss isn’t an engineer. He’s an author, podcaster and investor. If you’re not in one of those fields, the advice Tim could give (if he was gracious enough for an interview) would have to be restricted to the highly generic.

In fact, even if you are an author, podcaster or investor, it may not be the case that Tim Ferriss will offer super helpful advice. Why? Because Tim Ferriss is incredibly famous! For most people, Tim Ferriss isn’t 2 or 3 steps ahead, but instead more like a dozen or more. His advice for a new podcaster is going to be hampered by the fact that when he launched his podcast, he was already a minor celebrity. A lot of his personal experiences won’t translate to someone just getting started today.

The Strategy and the Map

To succeed in your career—whether that’s becoming a singer, starting a business, earning tenure or just getting a job—you need two things:

A strategy. This is a high-level, abstract process for generating career improvements.A map. This is a low-level, detailed picture of what your career looks like, concentrating on the areas that surround you.

The strategy is important—it’s one of the few areas where having the right approach to your career can make a big difference. Top Performer, is geared towards providing this half—giving a set of tools for thinking about your career and making progress.

But, in addition to your strategy, the map is essential. Importantly, you need to have the details about your immediate vicinity.

Imagine if you had to plan a trip, but you had only the map below?

Now contrast that with a map where all the roads have been filled in:

Regardless of where you are heading, the second map is going to get you much further. You’ll get lost less. You’ll know which streets are dead-ends, and which routes have traffic jams and where the expressways are. Without a map, you’re just wandering in the general direction of your goal.

Mistakes You’ll Make When Drawing Your Map

Being able to draw an accurate map is one of the skills Cal and I emphasize in Top Performer. Indeed, we spend the first two weeks of our course on developing the skills to get it right. Over the last several years of teaching the class, we’ve noticed all sorts of common mistakes that would-be career mappers make:

Obvious Career Mistake #1: You mostly ask for general advice.

Finding the right people, those people 2-3 steps ahead in their careers, is the first step. However, when talking to these people, many would-be mappers get mostly general advice—work hard, make connections, don’t give up. What gives?

The answer is that if you want good answers, you need to ask the right questions. Asking someone what they did, rather than for abstract advice, is a better question because it focuses on specifics, not generalities.

Obvious Career Mistake #2: You copy the surface, not the cause.

What time does the person wake up? Do they have a kale smoothie for breakfast or oatmeal? Apple or Android? None of these things matter…

Another mistake you can make in your map is looking at surface characteristics—obvious habits, quirks or beliefs that the person you admire holds. Instead, you have to look at what is driving their results. What skills have they mastered? What assets did they build? What projects did they cultivate?

Obvious Career Mistake #3: You plan a route that’s easy, even if it’s not pointed at your destination.

Often the kinds of efforts that will move forward your business are hard. They are uncomfortable. They require doing things that you (currently) have no idea how to do.

Many people pass on these to pick hobby projects instead. Projects that are fun, seem related to their career, yet, ultimately deliver underwhelming results. Improving their social media marketing, rather than creating compelling content. Installing a new development environment, rather than becoming an expert in their language. Designing business cards instead of drumming up business.

How Can You Avoid These Pitfalls?

Knowing how to draw a detailed and accurate map of your career is the first step. The second is knowing how to navigate it. How to cultivate the skills, assets and signals that will move you forward in the direction you want to proceed.

Cal Newport and I are going to be reopening Top Performer, our course for improving your career, next week. If you’re interested in joining us on an eight-week program to develop the tools to understand your career and make progress towards what really matters, we’d love to see you in the class.

#####

Unrelated Note: I just discovered that another longtime friend, Srini Rao, is hosting a cool looking conference, called The Architects of Reality, in Nashville in April. The reason it caught my attention is a rule he’s put in place: no laptops, no smartphones, no social media. You have to just listen, think, and, you know, talk to actual people.

I don’t have any particular skin in the game here, I just enjoyed seeing that rule so much I couldn’t help share it. Makes me happy…

October 27, 2019

On Digital Minimalism, Loneliness and the Joys of True Connection

Photo by Markus Meier.

Photo by Markus Meier.Earlier today, I came across a thoughtful essay written by someone just embarking on the digital declutter suggested in my most recent book. Summarizing the first day of his experience, the essay author was surprised by the sense of isolation he felt during his initial foray into public without his phone.

As he writes:

“Waiting in line for lunch is also usually an excuse for ‘productivity.’…but today I opted to leave it and simply look around the food hall. The first thing I noticed was that everyone was watching me — or I was scared they were, at least. While I generally enjoy being on stage, what I feared was that they were watching me be alone. And who wants to see that?”

He concludes: “And now I understand one potential uptake of embarking on a digital declutter — loneliness.”

In a previous post, I wrote about the challenge presented by the boredom that follows a commitment to paring down your online activity. Here, I want to tackle loneliness, as it’s another issue I hear about a lot when talking with those transitioning toward digital minimalism, especially younger people whose social lives have become intertwined with their phones.

As I write in chapter 4 of Digital Minimalism, in moderation, the loneliness felt in these moments of solitude is not necessary deleterious. I quote the following 1972 diary entry from the poet May Sarton:

“I am here alone for the first time in weeks, to take up my ‘real’ life again at last. This is what is strange — that friends, even passionate love, are not my real life unless there is time alone in which to explore and to discover what is happening or has happened. Without the interruptions, nourishing and maddening, this life would become arid. Yet I taste it fully only when I am alone…”

Sarton highlights a crucial point. Loneliness is a strong human drive that not only pushes us toward deep connection, but establishes the background against which true connection pops in vivid importance.

To fill every moment of solitude with a droning hum of twitter timelines and pull-to-refresh swipes reduces the nobility of our social nature. To instead face that moment of aloneness, like our essay writer in the food hall, uncomfortable and self-aware, but then later contrast that to sitting down with someone you care about, and actually, truly talking, is to taste life fully.

#####

Earlier this month, my friend Ryan Holiday’s new book, Stillness is the Key, was released. You probably already know and enjoy Ryan’s work, but in case you don’t, here’s my blurb from the book jacket: “Some authors give advice. Ryan Holiday distills wisdom. This book is a must read for anyone feeling overwhelmed by the frenetic demands of modern life.” If that resonates: check this one out…

October 21, 2019

A Piece of Advice I Wish I’d Included in My Book

Photo by Roman Harak.

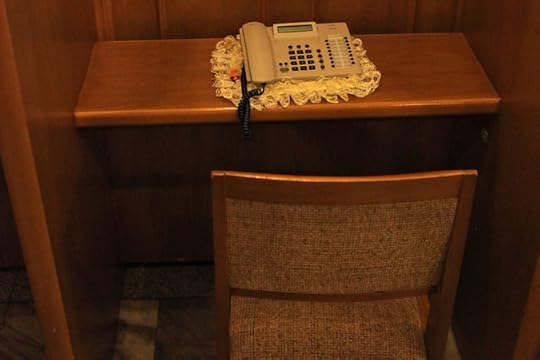

Photo by Roman Harak.One of the questions I’m often asked during interviews for Digital Minimalism is what advice I’ve learned more recently that I wish I had included in the book. There are several candidates for this missing advice, but one I’ve found myself talking about a lot recently is what I call the phone foyer method.

This strategy was innovated by parents who were worried about the negative effects of using their phone too much around their kids, but it applies more broadly.

The idea is simple…

The Phone Foyer Method

When you get home after work, you put your phone on a table in your foyer near your front door. Then — and this is the important part — you leave it there until you next leave the house.

If you need to look something up, you go to your foyer and look it up there.

If you need to send a text message, you go to the foyer. If you’re holding a back-and-forth conversation, then you need to stand there while you do it.

If you’re expecting an important call, put on your ringer.

If you feel the urge to check in on social media, it’s waiting for you in the foyer.

And so on.

(The one allowable exception: listening to a podcast or audiobook during tedious household chores. Let’s be reasonable…)

This method, of course, doesn’t require that you have a foyer, I just liked the alliteration. The key is that your phone stays in a fixed location while you’re at home instead of traveling with you as a constant companion.

Many who have tried this technique are surprised to discover the degree to which having a phone with them at all times completely transforms their experience when at home. We’ve become so used to the persistent fragmentation of our attention during our leisure hours that we’ve forgotten how recently this behavior arose.

To be clear, it’s not self-evident that home life before smartphones was better. The phone foyer method will provide you the before and after comparisons needed to decide for yourself.

But if you’re like a lot of people who have tried this method and reported back to me, once you rediscover the improved presence, the strengthened interpersonal connections, the mind-settling moments of solitude, and the doses of boredom that motivate meaningful, but difficult action — you’ll probably become a believer in the power of the phone-filled foyer.

#####

Another podcast recommendation: I recently joined Jia Tolentino, who wrote about Digital Minimalism for the New Yorker last spring, on Charles Duhigg’s How To! podcast. It was an interesting discussion. If you’re looking for more of my recent podcast appearances, check out my media page, I’ve listed 45 or so interviews from the past year.

October 16, 2019

The Atomic Minimalist: My Conversation with James Clear

Last October, my friend James Clear published the breakout hit book, Atomic Habits. As we both discovered in the months that followed, we have many readers in common. James’s habit-building framework, it turns out, is quite useful for those looking to increase the quality of their deep work or succeed in a transition toward digital minimalism.

In recognition of this overlap, and in celebration of Atomic Habit’s one-year anniversary, James and I recently recorded a podcast in which we geek out on the details of our work and how they overlap.

If you’re a fan of James, or are interested in learning more about how his ideas and mine work together, I recommend you give this conversation a listen (you can use the embedded player above, or access it directly here).

October 7, 2019

Not All Emails Are Created Equal

Interviews are a common part of the book publicity process, especially as you become better known as a writer. Between television, radio, print and podcasts, I ended up doing well north of 100 interviews about Digital Minimalism since its release last February.

Given this volume of appointments (which is actually modest compared to many authors), I arranged things with my publicity team at Penguin so that they could book interviews on my behalf. Using a service called Acuity, I specified what times I was available, and they then put interviews directly on my calendar during these periods, all without requiring me to participate in the scheduling conversations.

Viewed objectively, this setup shouldn’t have made a big difference in my life. Scheduling an interview takes around 3 or 4 back-and-forth messages on average. This adds up to somewhere around 300 or 400 extra emails messages diverted from my inbox.

When you consider that these scheduling threads were spread over six months, and that the average professional user sends and receives over 125 emails per day, the communication I saved with this setup should have been be lost in the noise of my frenetic inbox.

But it did matter. Not having to wrangle those scheduling emails provided a huge psychological benefit.

The observation that explains this discrepancy is that not all emails are created equal. In my experience, the cognitive toll of three or four back-and-forth scheduling emails, spread out over a day, is much greater than three or four standalone emails that each require, at best, a one-time reply.

The back-and-forth emails hurt more because they conflict with a social brain that has evolved to prioritize back-and-forth conversation with members of our tribe. When we send an email to someone and are awaiting their response, there’s a corner of cognitive real estate occupied by this ongoing transaction, nervous about the open loop, fueling a gnawing background hum of minor anxiety.

Rationally, we know it’s not crucial that we catch and respond to the next message in the exchange right away, but to our more primal circuits, honed on a deep historical scale that predates asynchronous communication, such distinctions are irrelevant.

Before I fall too far down a treacherous evolutionary psychology rabbit hole, let me step back to emphasize the general point at play in this example. When we think about email as an abstract digital information delivery service, we miss many of the subtle ways in which it causes more pointed miseries. If we want to get a handle on our current age of communication overload and knowledge worker burn out, we must first explore the specific manner in which this form of modern interaction clashes disastrously with our paleolithic brains.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers