Cal Newport's Blog, page 25

September 25, 2019

How Not to Be Alone: Jonathan Safran Foer on the Dangers of Diminished Communication

Photo by Pedro Ribeiro Simões

Photo by Pedro Ribeiro SimõesIn 2013, the novelist Jonathan Safran Foer gave the commencement address at Middlebury College. He subsequently adapted parts of it into a short but impactful essay published in the New York Times. It was titled: “How Not to Be Alone.”

In this piece, Foer explores the evolution of communication technology, writing:

“Most of our communication technologies began as diminished substitutes for an impossible activity. We couldn’t always see one another face to face, so the telephone made it possible to keep in touch at a distance. One is not always home, so the answering machine made a kind of interaction possible without the person being near his phone.”

From the answering machine we got to email, which was even easier, and then texting, which, being less formal and more mobile, was even easier still.

“But then a funny thing happened,” Foer writes, “we began to prefer the diminished substitute.”

This made life convenient, but introduced its own costs:

“The problem with accepting — with preferring — diminished substitutes is that over time, we, too, become diminished substitutes. People who become used to saying little become used to feeling little.”

Foer is underscoring a point I also elaborate in Digital Minimalism. We’re evolved to be highly social primates. Through the vast majority of our deep history, sociality meant analog communication, with vocal inflections, body languages, and a necessary investment of time and energy by both parties.

When you strip away these elements of interaction, you strip away a lot of what makes us human.

“We often use technology to save time,” Foer concludes, “but increasingly, it either takes the saved time along with it, or makes the saved time less present, intimate and rich.”

September 9, 2019

Our Brains Are Not Multi-Threaded

Photo by Anders Sandberg.

Photo by Anders Sandberg.In computer programming, it’s common to split your program into multiple different threads that run simultaneously, as this often simplifies application design.

Imagine, for example, you’re creating a basic game. You might have one thread dedicated to updating the graphics on the screen, another thread dedicated to calculating the next move, and another monitoring the mouse to see if the user is trying to click.

You could, of course, write a single-threaded program that explicitly switches back and forth between working on these different tasks, but it’s often much easier for the programmer to write independent threads, each dedicated to its own part of the larger system.

In a world before multi-core processors, these threads weren’t actually running simultaneously, as the underlying processor could only execute one instruction at a time. What it did instead was switch rapidly between the threads, executing a few instructions from one, before moving on to the next, then the next, and then back to the first, and so on — providing a staccato-paced pseudo-simultaneity that was close enough to true parallel processing to serve the desired purpose.

Something I’ve noticed is that many modern knowledge workers approach their work like a multi-threaded computer program. They’ve agreed to many, many different projects, investigations, queries and small tasks, and attempt, each day, to keep advancing them all in parallel by turning their attention rapidly from one to another — replying to an email here, dashing off a quick message there, and so on — like a CPU dividing its cycles between different pieces of code.

The problem with this analogy is that the human brain is not a computer processor. A silicon chip etched with microscopic circuits switches cleanly from instruction to instruction, agnostic to the greater context from which the current instruction arrived: op codes are executed; electrons flow; the circuit clears; the next op code is loaded.

The human brain is messier.

When you switch your brain to a new “thread,” a whole complicated mess of neural activity begins to activate the proper sub-networks and suppress others. This takes time. When you then rapidly switch to another “thread,” that work doesn’t clear instantaneously like electrons emptying from a circuit, but instead lingers, causing conflict with the new task.

To make matters worse, the idle “threads” don’t sit passively in memory, waiting quietly to be summoned by your neural processor, they’re instead an active presence, generating middle-of-the-night anxiety, and pulling at your attention. To paraphrase David Allen, the more commitments lurking in your mind, the more physic toll they exert.

This is all to say that the closer I look at the evidence regarding how our brains function, the more I’m convinced that we’re designed to be single-threaded, working on things one at a time, waiting to reach a natural stopping point before moving on to what’s next.

So why do we tolerate all the negative side-effects generated from trying to force our neurons to poorly simulate parallel programs? Because it’s easier, in the moment, than trying to develop professional workflows that better respect our brains’ fundamental nature.

This explanation is understandable. But to a computer scientist trained in optimality, it also seems far from acceptable.

September 2, 2019

On the Surprising Benefits of an Un-Mobile Phone

Photo by

Maarten van den Heuvel

.

Photo by

Maarten van den Heuvel

.A college senior I’ll call Brady recently sent me a description of his creative experiments with digital minimalism. What caught my attention about his story was that his changes centered on a radical idea: making his mobile phone much less mobile.

In more detail, Brady leaves behind his phone each day when he heads off to campus to take classes and study, allowing him to complete his academic work without distraction. As Brady reports, on returning home, usually around 6:00 pm, “I [will spend] 20 minutes or so responding to emails, texts, and the like.”

Then comes the important part of his plan: after this check, he leaves his phone plugged into the outlet — rendering it literally tethered to the wall.

His goal was to reclaim the evening leisure hours he used to lose to “mindlessly browsing the internet.” Here’s Brady’s description of his life before he detached himself from his phone:

“I would just rotate between Reddit, Facebook, and YouTube for hours. I was never even looking for anything in particular, I was just hooked on endless low-quality novel stimuli. I felt like there was so much wasted potential…I didn’t want to get old and realize that my life was spent scrolling on a backlit screen for 4 hours a day.”

Like many new digital minimalists, after Brady got more intentional about his technology, he was confronted with a sudden influx of free time. Fortunately, having read my book, he was prepared for this change, and responded by aggressively filling in these newly open hours with carefully-selected activity.

Here’s his summary:

“I did careful weekly and daily planning to find events to go to on campus and to plan out hobbies to explore. As a result of this planning, I was able to go to tons of random events at [my college] like free concerts, musicals, comedy shows and more. I also improved my attendance on my improv comedy team…Additionally, cooking and mixing drinks became a big hobby of mine and I would make multiple new dinner recipes and new cocktails every week.”

Not surprisingly, Brady also became more productive (“I’ve been able to get much more work done”). Perhaps more surprising, this increased disconnection unexpectedly improved his connection with others:

“I’ve become much better at simply talking to people and meeting new people because I can’t just pull my phone out to get through periods of boredom or awkwardness. Instead I just talk to people more, and as a result, I’ve grown closer to my friends…and I’ve made new friends by talking to random people throughout the day.”

Everyone’s experience with digital minimalism is different. What I like about Brady’s story is that he didn’t abandon the benefits of the smartphone, he just rejected the behavioral addendum that specifies you have to access these benefits constantly. For him, this subtle shift in his engagement made all the difference.

“The biggest change is that I no longer feel like I’m wasting my life away,” he told me. “I feel like I’m experiencing the world and living the human experience.”

######

On an unrelated note, as part of the research for an article I’m writing for a major national publication, I’m trying to get in touch with someone who worked with the Apollo program (or Mercury/Gemini). Given how long ago we’re talking about, I know this is a long shot, but if this describes you, or you know someone this describes who might be willing to chat, please send me an email at author@calnewport.com.

August 22, 2019

Is Our Fear of Smartphones Overblown?

Clip courtesy of the always amusing Pessimists Archive.

Clip courtesy of the always amusing Pessimists Archive.During interviews for Digital Minimalism, I’m frequently asked whether I think our culture’s concerns about new technologies like smartphones and social media represent a fleeting moral panic.

The argument goes something like this: There are many technologies that were once feared but that we now consider to be relatively tame, from rock music, to the radio, to the telegraph famously lamented by Thoreau. Isn’t our concern about today’s tech just more of the same?

This is a genuinely interesting question that’s worth some careful unpacking. My main issue with this approach to the issues surrounding smartphones and social media is that it implicitly builds on the following logical formulation:

A. There exist technologies that concerned us when new, but that turned out to be harmless.

B. Smartphones and social media are a new technology that concerns us.

C. It follows that we will later come to believe that smartphones and social media are harmless.

This syllogism, of course, is flawed. To make it correct, the existential quantifier in proposition A would need instead to be universal, as in every new technology that concerns us ends up tame.

But we know that this isn’t the case as there are many examples of technologies that sparked concerns that were ultimately validated. Think, for example, of nuclear weapons, unregulated industrial food safety, and television, which really did end up massively changing the American social fabric in the ways critics warned.

The real question then is what type of concerning technology are smartphones and social media: harmful or harmless? I don’t think we have a clear answer yet, but there’s enough evidence that it might fall into the former category that we can’t simply dismiss it without further interrogation.

Such nonchalance would be illogical.

August 17, 2019

“I Was Lacking in Enough Energy, Time and Attention”: Another Digital Minimalism Case Study

Something I’ve learned reporting on digital minimalists is that the definition of “minimal” differs greatly from person to person. As part of my effort to share more case studies about this philosophy, I thought it might be fun to visit someone who falls on the extreme end of this spectrum.

Robert (as I’ll call him) recently walked me through some of the major changes he instigated to reclaim his life from his devices. He summarized his reasons for this transformation as follows:

“I was lacking in enough time, energy, and attention to get the things done that I wanted or needed to do…I didn’t like getting insufficient sleep because I was browsing nonsense on my phone until the wee hours, or that I was stressed out with my professional work due to constant procrastination/distraction…or that I wasn’t exercising consistently because I’d happen to browse the same nonsense right when I was about to start.”

Driven by these somber realities, he came to a simple revelation: “life would be better if I cut back.” A decision, as it turns out, he took seriously.

Perhaps most notable among the many changes he executed, Robert replaced his smartphone with a Nokia 3310 (see the above image) — a popular alternative among the digital minimalists, as it boasts clean interfaces and its battery lasts forever.

He also setup parental controls on his main computer and gave the passwords to his wife. On most days, these controls are configured to provide him only 30 minutes to browse personal email and distracting web sites. He also moved his GTD productivity practice and workout logs to paper-based notebooks, and ditched his kindle for old-fashioned “physical” books.

As Robert explained, this extreme shift toward digital minimalism transformed his life:

“Time alone is better. I think I’m more productive, deliberate, calm, and mindful; better at professional work, and more consistent with exercise. I think I’m more present and in-tune with anyone that I’m interacting with, especially my kids.”

Like many others who make similar efforts to take back control of their life from technology, Robert found the experience somewhat disorienting: “I feel like an alien at times since the pace and nature of my day-to-day affairs is quite different from those that are not digitally minimalistic.”

But as Robert learned, the real alien behavior is arguably what everyone else is doing, with their heads buried in their phones, frantically tapping and swiping, saturated with anxiety and wondering why even after all this “busyness” they still feel like something is missing.

August 8, 2019

On the Art of Learning Things (Ultra) Quickly

In the first chapter of Deep Work, I argue that the ability to concentrate is important in part because it’s necessary to learn hard things quickly, and in our economy, if you can pick up new skills or ideas fast, you have a massive competitive advantage.

Some readers subsequently asked me how to best deploy their concentration to achieve these feats of accelerated autodidacticism. My answer has been to direct people toward my longtime friend, and occasional collaborator, Scott Young, who has spent years mastering the art of mastering things (c.f., his MIT challenge.)

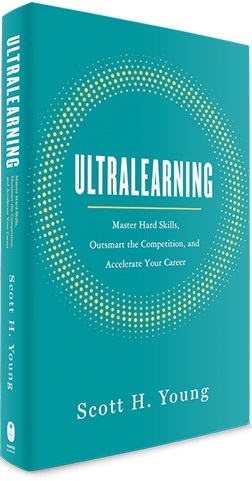

I’m happy to report that as of earlier this week, instead of simply waving vaguely in Scott’s general direction, I can now point to a brand new book that he’s published on the topic: Ultralearning: Master Hard Skills, Outsmart the Competition, and Accelerate Your Career.

In this book, Scott walks through his step-by-step process of breaking down a major learning project and pushing it through to completion much faster than you might have imagined possible. It’s important to emphasize that he provides no short cuts. If anything, he highlights the surprising hardness — in terms of concentration and drive — required to succeed with these endeavors; a point I’ve been underscoring since my early books on study habits.

But if you’re willing to invest the energy, and are looking for the right techniques to make sure this energy is not wasted to the friction of ineffective activity, this is the book for you.

#####

On an unrelated note, my most recent New Yorker article was published earlier this week. It takes a look at the history of email and applies ideas from my academic field, the theory of distributed systems, to help explain what went wrong with this innovation. If you like this blog, you’ll like this article …

August 4, 2019

“It’s Like I Couldn’t Stop”: A Digital Minimalism Case Study

A scene from the undisclosed North Country location where I’ve been living a minimalist life dedicated to writing, parenting loud boys, and dreading the administrative demands of the upcoming fall semester.

A scene from the undisclosed North Country location where I’ve been living a minimalist life dedicated to writing, parenting loud boys, and dreading the administrative demands of the upcoming fall semester.It’s hard to believe that it has already been six months since Digital Minimalism was released. (If you’re interested in browsing some of the interviews and press about the book, I’ve been doing my best to update my media page with some highlights.)

One of the nice things about having had some time pass since publication is that I’m starting to receive case studies from readers who have been experimenting with ideas from the book long enough to report results. I thought it might be useful to occasionally share some of these stories, especially for those who are still deciding whether or not to take the plunge with this philosophy.

I’ll start today with the saga of a reader I’ll call Jane…

As Jane explained to me, she was first exposed to a culture of constant connectivity when she took a job in politics in 2006, an era when Blackberrys ruled the political universe.

“I remember having a boss yell at me once because I went to the bathroom and didn’t answer my phone,” she told me. “No joke, I was told I should have left my Blackberry with the front desk for someone to answer.”

When social media apps and iPhones came along, Jane was well positioned to dive deep into that well of distraction, with Twitter, Facebook and Instagram becoming her primary vices.

“I was constantly on my phone: checking, scrolling, tweeting, liking,” she said. “It’s like I couldn’t stop.”

The cost of this behavior went beyond simply the distraction, or the rudeness of checking the phone when with other people (“I couldn’t control it!”). As Jane explained, there was also an emotional and psychological toll:

“I felt exhausted and burned out. Instagram and FB made me feel like shit. Seeing everyone’s picture-perfect lives was stressful. I knew it was BS but still tried to keep up…[I] felt like I was my overseeing my own personal PR.”

Earlier this year, Jane read Digital Minimalism. The ideas intrigued her, but she was skeptical she could go through with the suggested changes: “[I] didn’t think I could actually do it.”

Then, as Jane puts it, “fate stepped in”: she left her iPhone in an Uber and it took her a week to get it back. She was forced against her will to temporarily experience life without a constant digital companion.

“At first, I was super stressed but then an amazing thing happened: I felt great,” she said. “Relaxed, calm, it’s like I could think clearly. My brain felt less crowded. It’s like someone went in and swept out the cobwebs.”

When the phone returned, she decided to give digital minimalism a serious try. Though this practice looks different for everyone who adopts it, in Jane’s case, it meant that she deleted Twitter, Facebook and Instagram altogether. She also added blocking software on her computer to deter idle web surfing.

“I can’t say enough about how much becoming a digital minimalist has changed my life,” she reports.

Specifically, Jane found that dumbing down her phone “freed up SO much time,” she now listens to podcasts and “reads a ton.”

The emotional improvements have also been big. “Not knowing what every single loose connection is doing on Instagram is amazing,” she said. “That’s what I’ve realized: I don’t need to get [daily] updates about people who aren’t actually in my day-to-day life.”

As a reminder, digital minimalism isn’t about minimizing technology for the sake of minimizing technology — which would be a weird philosophy for a computer scientist like myself to promote. It’s instead about putting tools to work on behalf of the things you value most, and then ignoring the distractions that don’t clear this high bar.

For Jane, constant social media checks and idle web surfing weren’t supporting the things that truly mattered to her, and if anything, they felt like obstacles between her and things she cared about. When she became intentional about her digital life, as with some many others who have made similar commitments, her real world existence became much richer.

July 22, 2019

The Dynamite Circle: A Long Tail Social Media Case Study

Photo by Samuel Chou.

Photo by Samuel Chou.The Dynamite Circle has been on the periphery of my radar since my early days as a blogger. It’s a small, subscription-based social network operated by the Tropical MBA web site, which caters to entrepreneurs running small businesses from exotic locations (I’ve been a guest on their podcast a couple times).

This network, abbreviated simply as DC, has around 1200 enthusiastic members. In theory, these individuals could have found each other and organized on existing major social media platforms, using custom hash tags and Facebook Groups, or perhaps gathering on a sub-reddit, or subscribing to each others’ Instagram feeds.

All of this would be free and supported by slick apps with polished interfaces.

Instead, DC members pay around $500 a year to access a custom set of private forums: there are no sophisticated image recognition algorithms auto-tagging photos, or machine learning models carefully selecting posts to maximize engagement. And no one seems to care.

To help understand what’s going on here, I asked co-founder Dan Andrews if he’d allow me to lurk around the DC network for an afternoon. He graciously agreed. What I discovered gets to the core of the long form social media phenomenon I’ve been writing about recently (c.f., 1, 2).

Here’s what members do on the DC network:

They ask questions and offer advice on issues that are hyper-specific to the unique challenges of running location-independent small businesses. Some recent discussion topics I stumbled across in my casual browsing included: sharing experiences about using coach.me to improve productivity habits; describing a tool that makes it easy to test web sites from multiple different browsers; and a discussion of local marketing techniques.They arrange real world meetings with each other. On the third Thursday of every month, in cities around the world, DC members setup real world gatherings of local members. Last Thursday, there were gatherings in San Francisco, Melbourne, New York, Bangkok, Austin, Monterey and Portland, to name just a few cities among many. Beyond these more regular gatherings, members seem eager to setup ad hoc meetings. I quickly came across a post from someone visiting the bay area, looking for a group with which to talk shop, and someone else seeking volunteers to join them in their upcoming mountain bike trip in Bali. As Dan explained to me, this coordination of offline connection is crucial: “there’s so so so much that’s happened ‘beyond the forum’ amongst members.”

Large social media platforms are useful for easy distraction, yelling at famous people, and, more seriously, large-scale activism. But long tail alternatives offer something equally as powerful: real connection, freed from the artifice of the major services, with people you’d otherwise have a find time finding.

In the long tail, there’s no scrounging for attention, no trolls, no pile-ons by strangers who hubristically decree that you said the “wrong” thing, no desperate deception deployed through carefully curated photos, and, importantly, no compulsive over-use. Instead: just interesting people, putting aside some time to talk with some other interesting people in ways that makes their life better.

And on occasion, mountain biking together in Bali.

July 17, 2019

Blurring Offline and Online: More on the Potential of Long Tail Social Media

Photo by Ben Seidelman.

Photo by Ben Seidelman.Earlier this week, I began a discussion about long tail social media. The premise behind this trend is that as our internet habits mature, we no longer need social platforms with massive user bases.

I’m cautiously optimistic about this model as I think niche networks can better deliver on the promise of the social internet while avoiding pitfalls like engineered addiction and emotional manipulation. (These smaller alternatives also tend to be better on the legal-techno geek issues like data privacy and effective contention moderation.)

In response to my recent post on this topic, a reader pointed me toward a fascinating long tail social media case study that I wanted to briefly share, as I think it helps underscore the potential of this movement.

In 2017, serial entrepreneur Gina Bianchini launched a new startup called Mighty Networks. Fellow net nerds might remember Bianchini from her 2007 company, Ning, which let users setup their own customized social networks. Ning was ahead of its time, as it launched in a period when most people were largely unfamiliar with social networking. Mighty Networks is trying again: but this time focused on mobile devices and pitching to an audience much more familiar with this mode of interaction.

The basic idea is that individuals use the software to setup custom social networks for their existing communities. The network operates like a fancy Facebook Group, with discussions divided into topics that you can easily browse and join. It also makes it easy to setup mastermind groups, virtual conferences, and offer courses.

The example networks I saw were focused (a couple thousand users at most), and typically charged subscription fees from the users (eliminating the need to sell ads or harvest data).

The feature, however, that really piqued my interest, and instigated this post, is the ability to find community members near you in the physical world.

To be more concrete, consider the specific Mighty Network that was originally brought to my attention: The Little Black Dress Academy — a small-size, exclusive social network for women business leaders.

If you’re a member of this network, and enjoy the discussions, you’re encouraged to use a built-in feature that lets you find women leaders who live nearby so you can setup offline get togethers. Similarly, if you’re traveling, you can find members in the city you’re visiting and setup an impromptu coffee date or dinner — injecting a jolt of extra value into the trip.

This blurring of the offline and online would never work on a mass market platform like Facebook or Twitter — could you imagine! — but on small networks, made up of paying members with pre-existing bonds, it provides a major boost to the social value the online tool generates.

This is just an isolated example, but it hints at an intriguing conclusion I’ve been interrogating in my recent work: perhaps in attempting to consolidate the social internet into a small number of massive platforms, we were accidentally stripping away much of the potential of this technology to actually make us more social.

July 15, 2019

Thinkspot and the Rise of Long Tail Social Media

Last month, Jordan Peterson announced he was launching his own social media platform called Thinkspot. Details of the planned service are still sketchy, but it seems like it will include some novel features, such as subscription fees that support the content creators, and a commenting system meant to encourage deeper discussion.

Much of the early press coverage of Thinkspot has focused on the controversies surrounding Peterson and the tumultuous circumstances that led to the service’s creation.

To me, however, there’s a more interesting story lurking. What matters is not why Thinkspot exists, or even whether it will succeed, but instead the larger trend it represents.

The first generation of social media companies adopted a mass audience model: their value proposition depended on gathering the largest possible user base. You joined Facebook, in part, because of the promise that many people you already know were members, and you browsed YouTube because of the promise that it could offer an endless library of clips.

This model naturally supports monopoly and suppresses innovation. It’s conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley that a big reason why there have been no major social media platforms launched since 2011 is that it’s impossible for a new entrant to compete with the value produced by the massive audiences of the existing sites.

Why would I join a network with 10,000 users when one already exists with over 1,000,000,000?

As Thinkspot demonstrates, however, this mass audience strategy is starting to fray. As users become more familiar with both the joys and depredations of the attention economy, they’re increasingly shifting toward a long tail model for the social internet.

In this new model, users don’t want to connect with everyone they already know, but instead want to connect with small groups they find really interesting. Similarly, they don’t need access to massive libraries of low-quality content, but instead want access to curated collections covering topics they really care about.

The old model requires massive audiences before a given platform becomes useful. The new model does not.

If you’re deeply committed to the Intellectual Dark Web, for example, then Thinkspot will probably return you much more value than Instagram or Twitter, even though its audience size is a minuscule fraction of these giants.

Similar micro-platforms could be created for almost any other targeted interest that you can imagine, from paleo enthusiasts, to the FIRE community, to cricket fans, to Christian parents.

(See my recent New Yorker article on indie social media for more on some of the new tools that simplify the task of creating these new platforms.)

Put another way: In the world of long tail social media, network effects are much less important than interesting networks.

The internet, of course, has long been home to small communities dedicated to niche topics, organizing themselves through loose collections of websites, blogs, and existing social platforms.

The key insight of long tail social media — as epitomized by Thinkspot — is that there’s value in creating more unified and optimized online homes for these small communities: reducing the friction required for interaction and increasing its quality; yet also sidestepping the mass audience model’s imperative to grow your service as big as possible.

I’m not sure if this long tail model will successfully supplant the mass audience strategy that dominates today (any time there are hundreds of billions of dollars at stake, disruption is complicated). I hope, however, that it does, as it would almost certainly increase the value people get out of the internet, while helping to reduce some of the worst side-effects of our current dependence on rapacious platform monopolies.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers