Cal Newport's Blog, page 21

April 1, 2020

On Productivity, Part 2

Yesterday’s discussion about productivity and the deep life sparked a really interesting conversation, both in the comments section and my inbox. I thought it might be useful to continue with this topic and see where we end up.

A crucial distinction that seemed to arise from this back-and-forth was between productivity in the business context versus the personal context.

In the business context, productivity refers to the efficiency with which an input is converted into a more valuable output. When applied to workers it refers to the amount of value they are able to produce per unit time spent working. The goal of increasing productivity, roughly speaking, becomes to increase the output reaped for a given salary investment.

It’s this formulation that seems to be creating unease, as it’s one in which productivity is about reducing the quality of the worker’s life, by pushing for ever more frantic output, to increase the return on capital.

Marx originally worked out the basics of this framework with industrial manufacturing in mind, but over the past decade or so, knowledge workers suddenly forced to answer emails at all hours, or exhausted contractors serving the output-driven, algorithmically-mediated gig economy, are beginning to similarly experience this pressure as exploitation.

Business productivity is, of course, a rich topic, having been studied and argued over with vigor since the mid-19th century. (I’m convinced, for example, that in knowledge work, we’re miserable in part because we are working in ways that unproductively clash with our human brains. By making us more productive in the sense of making work more compatible with human nature might actually make our efforts less stressful and more satisfying.)

But let’s put this aside to instead consider productivity in the personal context. Here I’m referring to the individual’s desire to produce “value” in their life, where “value” can be a nebulous term, encapsulating aims like meaning, satisfaction, impact, etc.

I equate productivity in the personal context to a combination of two forces, organization and intention, united toward increasing the quality of your life. To be productive here is to enforce some organizing structure on the inputs and obligations pulling at your attention, so you can sort through what matters and what doesn’t, minimize energy wasted on activities that add little to your experience, and overall become much more intentional about where you direct your attention.

In this context, the connection between productivity and volume of output is severed. What matters instead is intention. If you eschew productivity in your life, you end up adrift, buffeted by the avoidance of pain and pursuit of positive chemicals. If you embrace it, you can cultivate a deep life worth living — one that might easily intertwine a long walk thinking about a book, with a long afternoon wrangling your kids. In this sense, all of the world’s great wisdom traditions can be understood, in part, as offering ancient productivity advice (among many other things).

The reason I’ve preserved “productivity” as the term of art for this second context is that it still accurately describes the goal of producing the best output you can with what you’re given. The floor, however, is open: Is this split useful? Do we need new terminology here?

March 31, 2020

On Productivity and the Deep Life

Earlier today, a reader and fellow professor sent me an interesting question:

“Everything you write is underpinned by productivity discourse. As I note above, I do embrace your approach to writing and thinking—the need for sustained thinking in quiet (sometimes outdoor) places, its deep pleasures (as well as difficulties), and its contribution to a deep life—but the productivity language is an impediment for me…The pleasure in thinking and doing things well is such a deep-wired human pleasure, if we attend to it, and it feels (to me) diluted when it’s linked to productivity…Short question, then, is: could you promote deep work without linking it to productivity?”

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the connection between productivity and the deep life, so the timing of this question is good (though let me caveat the following answers by underscoring their preliminary status).

Let me start with the positive, the role productivity plays in crafting a meaningful life. I propose two responses. The first is that in many contexts, many shallow tasks — filing forms, pay taxes — cannot be sidestepped. If you can carefully organize these efforts and execute them efficiently, leaving a minimum footprint on your cognitive landscape, you leave more space for more meaningful endeavors. (It’s a cliche in the productivity world that the most organized people tend to have the most relaxing vacations.)

My second response builds on the following point made in the above question: “The pleasure in thinking and doing things well is…deep-wired.” I think this is absolutely true. Thoreau retreated to Walden Pond, in part, to do nothing — to just observe and live deliberately — but he also wrote a first draft of a book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, while in his cabin. He then left the pond to move in with Emerson, where he wrote another book, this one about his experience at the pond, then another soon after, Civil Disobedience. Thoreau found peace observing nature; but his real pleasure was in producing enduring work.

Which is to say that the human instinct to produce meaningful output — to see one’s intentions made concrete in the world (to paraphrase Matt Crawford) — is fundamental. Doing nothing can provide a transient respite to an overtaxed mind, but it’s not a state in which our species can thrive long term (see, for example, Victor Frankl’s powerful work on logotherapy).

These are the two side of the productivity coin: minimizing the shallow and amplifying the meaningful. It’s an objective, in other words, intertwined into the cultivation of a deep life.

This brings me to the negative aspect of the question: the distaste with the term “productivity.” I’ve heard this feedback often, especially in recent years, but almost exclusively from academic or academic-adjacent circles. This is, I think, largely a semantics issue.

Many frameworks in modern academic thought are influenced by labor politics. In this context, “productivity” is stained with an enduring Marxist critique of exploited labor. But when you recontextualize “productivity” from an aggregate industrial metric to an autonomous personal endeavor, its valence radically shifts from exploitation to empowerment. I’m happy, in other words, for some to replace the term “productivity” with a synonym if it makes it more digestible. What matters to me is the underlying importance of our instinct toward getting things done.

March 30, 2020

The Inconvenient Popularity of Podcasts and Group Texts

Last April, Jia Tolentino wrote an article for The New Yorker that reviewed my book, Digital Minimalism, along with Jenny Odell’s book, How to Do Nothing, which came out around the same time. Tolentino’s piece thoughtfully weaved many different strands of observation, each of which is worthy of its own dissection.

There was one point, however, made in one of her final paragraphs, that I wanted to highlight. Tolentino, reflecting on what her life was like during the month she experimented with the digital declutter recommended in my book, wrote the following:

“It occurred to me that two of the most straightforwardly beloved digital technologies—podcasts and group texts—push against the attention economy’s worst characteristics. Podcasts often demand sustained listening, across hours and weeks, to a few human voices. Group texts are effectively the last noncommercialized social spaces on many millennials’ phones.”

This comment was made in passing, but I think it’s profound. An argument I’ve been advancing for a while is that the social media behemoths that currently dominate the internet are unique in economic history in their combination of massive market valuations and cultural dispensability. Hundreds of millions of people use Facebook, Instagram and Twitter every day. Few of these users, however, need these services to live a thriving life.

The underlying decentralized protocols of the internet existed before these services and will exist after they’re gone. Competitive methods to seek entertainment or connect with family and friends can leverage this fundamental technology to find audiences. In this scrum, disruption can easily arise, which is why the success of podcasts and group texts is so important. They’re an inconvenient reminder that you don’t need massive, addictive, Orwellian, cumbersome platform monopolies for people to find deep value in the internet.

(For more on these alternatives, see, for example, the article I wrote for The New Yorker a month later about indie social media platforms.)

March 29, 2020

The Deep Benefits of Learning Hard Things

A reader pointed me toward a useful piece of advice from a recent episode of Joe Rogan’s podcast. Talking with comedian Bryan Callen, Rogan noted the following:

“When you put yourself in a situation where you really suck at something, it’s really good for you, it’s good to suck at things and try to get better at them…when you learn how to do something you suck at it first, you have to concentrate at getting better, that thing of getting better translates to other aspects of your life…if you can get good at learning how to play the piano you can get good at archery…there’s a thing in there of learning how to learn.”

This is an idea I’ve come across repeatedly during the research I’ve conducted for my various books. There’s something incredibly valuable in the deeply frustrating yet rewarding pursuit of mastering something hard. As Rogan correctly notes, when you practice the art of practicing, the skill can be applied widely . It’s why spending time to learn the piano, or archery, or chess, or hobby electronics can be more than a high quality alternative to the numbing blandness of passive information consumption, it can also make it easier later when you decide at work you need to master a complex new mathematical model or supply chain system.

There is, of course, also a psychological benefit to learning and then practicing a skilled craft, especially during otherwise chaotic times. As Rogan notes earlier in the interview: “you focus, then you execute, and if you do it properly, there’s a meditative aspect to it.”

(Photo by Kansas Tourism)

March 28, 2020

The Underappreciated Impact of the Attention Redistribution Revolution

I launched this site during the period sometimes referred to as the “golden age of blogging”: the years from 2003 to 2009 when independent, inexpensive to run, sometimes highly-influential blogs threatened to upend the world of traditional media. By 2010, however, that cultural energy had been redirected toward a new form of online expression that had become recently ascendent: social media.

What explains this shift? A common explanation is simplicity and cost: it’s easier to setup a Twitter account than a WordPress server, and the former is free. I’ve never felt, however, that this provided a full explanation. There were, at the time, many services that allowed you to simply setup a blog and host it for free, and if the demand had been there, these services could have significantly increased their scale and features.

It’s also worth remembering, as Jaron Lanier pointed out in his 2010 manifesto, You Are Not a Gadget, that social media offered an impoverished means of expression as compared to an open-ended blog. Services like Facebook, he noted, force you to discretize yourself into checkbox selections and binary nods toward content you “like.”

So what then explains why social media became the new default method for internet expression? In Deep Work, I point to an often overlooked contributing factor: attention.

One of the properties that made blogging so exciting is that it bypassed the gatekeepers guarding traditional media outlets. Anyone could start a blog. Everyone had access to the same global audience.

As the vast majority of bloggers during the golden age discovered, however, the “gatekeepers” weren’t the only thing standing between them and a rapt audience. It turns out that it’s really hard to engage peoples’ attention, even once you have access to it. A lot of people lost enthusiasm for blogs, in other words, because there was little enthusiasm for their blogs.

Part of the underappreciated brilliance of early social media is that it presented an entirely novel solution to this problem. Networks like Facebook offered its users what can best be understand as a semi-collectivist model of attention. Users could post whatever they wanted. By an unspoken social contract, they would pay some attention to the posts of their close neighbors in the network social graph (regardless of the quality of this content), and these neighbors would do the same. The result: everyone could almost immediately begin receiving attention from an audience — a deeply appealing promise that through most of modern history had been available only to relatively small number of professions (writers, preachers, media personalities, teachers).

This attention redistribution was the hidden revolution instigated by social media. It solved a remarkably big problem facing the social internet: how to move beyond efficiently spreading bytes over networks to also efficiently spreading attention. And by doing so, it completely transformed the cultural landscape.

I’m not trying to label this phenomenon as either good or bad. Indeed, the major issues that have soured people on social media in recent years stem from largely unrelated issues involving engineered addiction, manipulation, and privacy. I think it’s important to understand the attention redistribution revolution mainly because it’s been incredibly impactful, and if you don’t understand how we got to now, it’s hard to figure out where best to try to go next.

March 27, 2020

Benjamin Franklin on the Balance Between Solitude and Company

In response to yesterday’s post about quiet creativity, a reader asked the following question in the comments:

“Here’s my question: How can digital minimalism and deep work be adapted for extroverted people who want to do deep work and lead a digital minimalist life — but also satiate a voracious appetite for human interaction?”

A few other commenters subsequently emphasized this question, which I think is a good one and worth discussion. We can find some insights into this issue in the journals of a young Benjamin Franklin. In August 25, 1726, a twenty-year-old Franklin was more than a month into sea voyage from London back to Philadelphia when he recorded the following entry:

“I have read abundance of fine things on the subject of solitude, and I know ’tis a common boast in the mouths of those that affect to be thought wise, that they are never less alone than when alone. I acknowledge solitude an agreeable refreshment to a busy mind; but were these thinking people obliged to be always alone, I am apt to think they would quickly find their very being insupportable to them.”

There’s a healthy dose of Aristotelean moderation in this observation. Time alone with your thoughts is necessary: it refreshes your mind and enables insights. Too much time alone, however, quickly becomes “insupportable.”

This is, I believe, a reasonable answer to my reader’s question. Embrace your extroversion, but not 100% of the time. A quiet walk in the woods, or a summer spent staring at the rolling Atlantic, will serve its purpose, but such seclusion need not become a total way of life.

March 26, 2020

From the Archives: On Quiet Creativity

I’ve been writing posts for calnewport.com since July, 2007. This was soon after I finished all of my coursework and qualifiers for my doctorate at MIT, which I had tackled concurrently with writing and publishing my first two books. Which is all to say that by the summer of 2007 it suddenly seemed like I had a lot of free time on my hands. My solution to this state of affairs? This blog.

In recent days, in a fit of nostalgia, I’ve begun browsing my voluminous archive. I thought it might fun to every once and while briefly revisit a post from the past that I particularly enjoyed.

I’ll start with an entry from January, 2014. It’s titled: “On Quiet Creativity,” and it opens with me talking about hiking the trails near Georgetown’s campus (see above), working on a thorny proof.

Here’s the thesis I extracted from the experience:

“When I talk about my purposefully disconnected life, a common retort is that I’m missing out on the creative possibilities born of the frequent exposure to new people and ideas delivered through social media and related technologies.

But here’s the thing, for the most part, this is not how high-level creative work is accomplished. It’s not, in other words, lack of input that stymies creative breakthroughs.

…

What does stands in the way of creative breakthroughs — I’m increasingly convinced — is lack of time spent walking quietly with your thoughts, working and re-working your understanding of a concept in search of new layers of meaning.”

A few reflections on this post:

When I wrote those words back in 2014, I was getting lots of pushback about the fact that I didn’t use social media. It really did baffle and concern people. Today, my abstention is considered reasonable. It’s amazing how much our society has shifted on this issue.

I still really believe in the idea of quiet creativity. Gathering inputs is the easy part. It’s the long thinking, and rethinking, then thinking again that’s really needed if you want to produce industrial strength insights.

I believe (but am not positive), that this is the paper that resulted from the long thinking walks described in that post. It ended up published in October of that year.

March 25, 2020

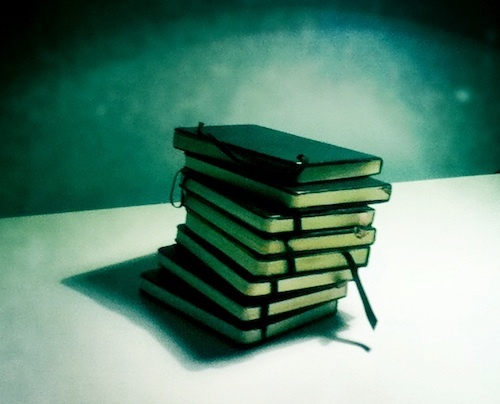

Thoughts On Notebooks

I’ve been using Moleskine notebooks since 2004, when I bought my first at the MIT bookstore. As I discuss in Digital Minimalism, high quality paper notebooks like Moleskines have historically played an important role in self-development because they provide a method to structure your interior life.

Thoughts, concerns, ideas, aspirations: these flow constantly through our consciousness. Ink on paper puts a stake in the ground that you can cling to amidst this turmoil, enabling you to build some scaffolding on which to organize these musings, while the persistent nature of the medium allows you to witness an evolution of this structure as you fill more pages over time.

This hard work of self-reflection is slow. It generates no “likes” and it doesn’t instantaneously banish boredom. No one else will read your notes and applaud your virtue or wit, and your future self will likely cringe at what you record now.

But without these efforts you’re adrift: pushed by whims, manipulated by attention economy contraptions, taking one step backwards for each step forward in your attempts to build a deep life.

I was prompted to write this post after someone pointed me toward the distressing fact that Moleskine started a social network called myMoleskine. It allows people to publicly share their notes and follow other Moleskine users. A development for which I have only one official reaction: Sigh.

March 24, 2020

From Mammoths to Time Management

In 1973, the BBC aired a 13-part documentary television series called The Ascent of Man. It was written and hosted by the polymath intellectual Jacob Bronowski, and following the lead of the BBC’s 1968 hit series, Civilization, it featured poetic commentary set against dramatic visuals.

Which is all to say, I was excited to recently come across a copy of the series’s companion book: a handsome large-format hardcover that largely replicates the commentary from the television show and is thick with full-color photos. (I’ve always loved sweeping science histories. I’m concurrently reading, off and on, a vintage copy of Richard Leakey’s 1978 book, People of the Lake, and Niall Ferguson’s latest, The Square and the Tower.)

I wanted to briefly share an interesting nugget I came across early in Bronowski’s book about the consequences of our ancestors’ shift toward an omnivorous diet:

“Meat is a more concentrated protein than plant, and eating meat cuts down the bulk and the time spent in eating by two-thirds. The consequences for the evolution of man were far-reaching. He had more time free, and could spend it in more indirect ways, to get food from sources (such as large animals) which could not be tackled by hungry brute force. Evidently that helped to promote (by natural selection) the tendency of all primates to interpose an internal delay in the brain between stimulus and response, until it developed into the full human ability to postpone the gratification of desire.”

The science on human evolution has taken astounding leaps since the 1970s, so I have no idea whether or not paleo-anthropologists still think it was the rewards of big game hunting that selected for the breaking of the stimulus and response loop in our brains. But I do know, based on some recent interviews I conducted with neuroscientists for a new book I’m working on, that this development — which gave us the ability to plan — is both largely overlooked, and remarkably central to basically everything great and terrible our species has done since.

More than anything, however, I like the neat just-so story implied by this passage: from our want of mammoths we eventually ended up bound by the tyranny of time management.

March 23, 2020

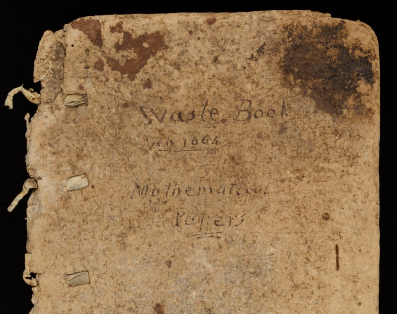

Newton’s Productive School Break

In 1666, Cambridge University closed its doors to help stop the spread of the black plague. This sent a precocious 23 year-old student named Issac Newton back to Woolshtrope Manor, a family estate located 60 miles northwest of the school. Newton’s main diversion: a thick, largely empty, 1000-page commonplace notebook that he’d inherited from his stepfather.

Newton decided to fill in its pages with his answers to an increasingly difficult series of mathematical questions he devised for himself. In doing so, he invented calculus.

Not bad for a school break.

If you’re interested in learning more about Newton’s miraculous year:

Check out this history, published recently by Jonathan Kujawa on 3 Quarks Daily (if you don’t know this website, ask any science geek you know to explain it to you). This was the article that inspired this post.

You can browse Newton’s notebook online via Cambridge’s digital library.

You can find nice images of Woolsthorpe Manor and its grounds here, and watch a short video about Newton’s work at Woolsthorpe here.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers