Cal Newport's Blog, page 18

June 26, 2020

On the Exceptionalism of Books in an Age of Tweets

Early in his 1994 essay collection, The Gutenberg Elegies, literary critic Sven Birkerts tells a story about his experience teaching an undergraduate course on short stories. He started his students easy, with some Washington Irving, then moved on to Hawthorne and Poe before arriving at Henry James.

It was here that his class “derailed.”

He tried to solicit opinions on the story he’d selected, but came up short. “My students could barely muster the energy for a thumbs-up or -down,” he writes. “It was as though some pneumatic pump had sucked out the last dregs of their spirits.”

As he probed, Birkerts realized the issue wasn’t localized; it wasn’t just the vocabulary, or the diction, or the specific references. The root drove deeper:

“They were not, with few exceptions, readers — never had been; that they had always occupied themselves with music, TV, and videos; they had difficulty slowing down enough to concentrate on prose of any density.”

As he reflected on this reality he came to realize that the implications were “staggering.” This was not just a “generational disability,” but instead a “permanent turn” in the human endeavor.

It’s easy to dismiss such sentiments as nostalgia: everything changes; it’s reactionary to become too enthralled with any particular aging technology. But Birkerts convincingly argues for a literary exceptionalism of sorts:

“For in fact, our entire collective subjective history — the soul of our societal body, is encoded in print. Is encoded, and has for countless generations been passed along by way of the word, mainly through books.”

As I elaborated in last week’s episode of my podcast, Neil Postman argues that it was the introduction of mass-produced longform writing that really unleashed human potential — ushering in the modes of critical, analytical understanding that birthed both the enlightenment and the scientific revolution, the foundations of modernity. It allowed us to efficiently capture complex thought in all its nuance, then build on it, layer after layer, nudging forward human intellectual endeavor.

Writing was not just another technology, in other words, but the cognitive lodestone that attracted all advances that followed.

Which is why Birkerts was troubled in the early 1990s to see an emergent electronic culture destabilize this medium.

It’s also why in 1985, Neil Postman described a similar ominous premonition as he surveyed the impact of television.

And it’s why today, as I see more of our political and philosophical discourse mediated through Tweets, I despair, but as I also see the emergence of longform audio and the resurgence of audio books, I feel hope.

As I elaborated in my podcast, the medium through which you mediate the world matters. An app on your phone can offer you diversion or fleeting catharsis. On the other hand, something more lexicographically substantial — though perhaps, as Birkert’s students discovered, more difficult to consume — can often offer true progress.

June 19, 2020

On Social Media and Character

Madison Fischer, a professional sport climber, recently pointed me toward an insightful essay she published on her blog about her battle with social media.

Early in her climbing career, Madison was exposed to Instagram. At first she posted pictures of her cat; then pictures of competitions; then her training; then she had a professional account where she could carefully track the demographics of her viewers, optimizing when she posted, and synchronizing her online behavior with a carefully-calibrated content calendar.

This sudden influencer status was impossibly appealing:

“I wanted the congratulations. I wanted admiration. I wanted my follower count to grow. I wanted everyone to envy my life and achievements. I wanted, no, needed people to tell me I was going places…But you can’t blame me. It’s so easy, so stimulating. It’s not even a statement that you have Instagram, it’s assumed. Everyone’s doing it.”

But something didn’t feel quite right about the increasingly artificial life she was constructing online. Beyond the “obvious egotism” issues, she began to lose touch with her true self: “I started believing this narrative of a girl…living the dream,” she writes, “traveling around the world to compete while finding the time for school, work, and a relationship.”

This became a problem:

“This story blinded me to the many mistakes I had along the way. I couldn’t step out of the reputation… Pride in my accomplishments made me content, and contentedness is poison to a young athlete who has to stay hungry if she wants to stay competitive.”

Madison eventually made a bold decision: she would quit Instagram. As she elaborates, it actually took her months of false starts and failed attempts to get to this place. At first, she tried partial solutions. She would delete the app, but it was still too easy to just Google “Instagram” and log in using her phone’s browser. She unfollowed everyone to empty her feed, but she still felt compelled to compulsively document her life.

So she finally had to get rid of her account altogether. “My exit from social media was a quiet one,” she writes. No big post announcing her decision. No warnings. Just silence. She was free.

It was then that Madison’s athletic career moved to the next level. “There’s nobody I’m here to perform for,” she writes. “I just train and silently work on achieving my own definition of success.”

Without the need to document and promote her daily activities, Madison regained a sense of self-motivation. She was honing her craft for her own reasons.

Three months after going off the grid, she traveled to the biggest event in her competition calendar, the Canadian Open Boulder Nationals. She wasn’t looking at posts showing her competitors preparing, and she wasn’t thinking about how her performance would play online. As a result, she “felt overwhelming ease” and was “able to perform at my capacity.”

She won second place.

What struck me about Madison’s story was not the impact her decision had on her training, or focus, or performance, but instead the way it transformed her character.

Here’s how she describes her mindset heading into Nationals:

“I wanted to see what I could do. Nothing to do with you, or your friends, or the neighbors, or the members at my gym, or my competitors, or family. It was all within, as it should be, and as it has to be.”

This issue is often overlooked when people consider the role of tools like social media in their lives. They consider factors like audience-building, entertainment, discovery and connection, and weigh them against obvious costs like distraction and privacy. But a deeper question lurks beneath this debate: are these services making you a better or worse version of yourself?

######

I want to thank everyone who took on my challenge from earlier this week to donate to a pair of excellent organizations working on police reform. Over 70 of you stepped up and made donations that added up to roughly $7,000. As promised, I matched every dollar.

June 16, 2020

Facebook’s Fatal Flaw?

In Episode 4 of my Deep Questions podcast (posted Monday), a reader named Jessica asked my opinion about the future of social media. I have a lot of thoughts on this issue, but in my response I focused on one point in particular that I’ve been toying with recently: Facebook may have accidentally developed a fatal flaw.

To understand this claim, we have to rewind to the early days of this social platform. The original pitch for Facebook was that it made it easier to connect online with people you knew. The content model was simple: you setup a profile, people you knew setup profiles, and everyone could then check each others’ vacation pictures and relationship statuses.

For this model to be valuable, the people you knew had to also use the service. This is why Mark Zuckerberg focused at first on college campuses. These were closed communities in which it was easy to build up enough critical user mass to make Facebook fun.

Once Facebook moved into the range of hundreds of millions of users, competition became difficult. The value of a network with a hundred million users was exponentially larger than one with a million, as the former was much more likely to connect you with the people you cared about. It was on the strength of this model that Facebook emerged as a powerful social internet monopoly.

The problem, however, was that they weren’t making enough money.

As their IPO loomed, Facebook executives feared that the appeal of checking the profiles of friends and family wasn’t strong enough to get people to use the service all day long. It was an activity you would occasionally do when bored; they needed to find a way to make their platform stickier.

So Facebook did something radical: it blew up its original content model and replaced it with something novel: the bottomless scrolling newsfeed. Instead of checking the profiles of friends and family, you now encounter a stream of articles sourced from all over the network, handpicked by optimized statistical algorithms to push your buttons and stoke the fires of the elusive quality known as engagement.

Facebook shifted from connection to distraction; an entertainment giant built on content its users produced for free.

This shift was massively profitable because it significantly increased the time Facebook’s gigantic user base spent on the platform each day. Tapping that blue and gray icon on your phone now promised instant satisfaction, and our days are filled with endless moments were such appeasement is welcome.

The thought that keeps capturing my attention, however, is that perhaps in making this short term move toward increased profit, Facebook set itself up for long term trouble.

When this platform shifted from connection to distraction it abdicated its greatest advantage: network effects. If Facebook’s main pitch is that it’s entertaining, it must then compete with everything else that’s entertaining. This includes podcasts, and YouTube, and streaming video services, not to mention niche long tail social media platforms that can’t offer you access to your old roommate, but can connect you with a small number of people who are interested in the same things as you. Meanwhile the social interactions that used to occur on these platforms have moved to more flexible and simpler mediums, like group text messages. Facebook used to be the place where grandparents sought new baby pictures. Today, these images are just as likely to be spread in a nondescript iMessage thread, with no creepy data mining or malicious attention engineering required.

I’m not so sure that a newsfeed made up of posts and links generated by random social media users can compete with this increasingly optimized world of targeted entertainment and streamlined digital socialization. Facebook found a way to grow to a market capitalization of $600 billion, but may have accidentally crippled itself in the process.

Or not. But one thing I know for sure is that it would be myopic to believe that the future of social media is going to look just like it does today.

June 15, 2020

Small Steps

Last week, I asked for your help in identifying organizations that have had some success working on issues surrounding police violence.

My instinct when facing an overwhelming problem is to find at least one place where some improvement is possible, find people who are having success with these improvements, then give them support to help them keep going. Such steps are small in the short term, but they have a way of breaking the complacency of standing still, which in the long term can end up making the difference between transformation or frustration.

Over 60 of you sent me notes, pointed me toward organizations, and provided reading lists. This was massively helpful. I have sorted through this information to identify two organizations in particular (among many) that seem to be having success in this policy area, and that apply the type of data-driven approach I thought might appeal to my audience here:

Campaign Zero

Center for Policing Equity

I encourage you to donate if you can. If you do, forward me the receipt. To the extent I’m able, I’ll match these contributions dollar for dollar.

June 12, 2020

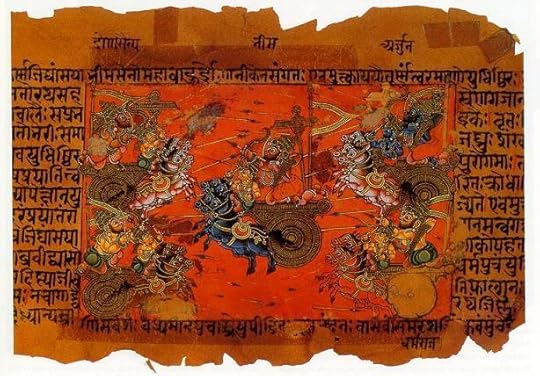

Ancient Complications to Modern Career Advice

In 2012, I published a book titled So Good They Can’t Ignore You. It argued that “follow your passion” was bad career advice. I didn’t claim that passion was a problem, but instead argued that it was too simplistic to assume that the key to career satisfaction was as easy as matching your job to a pre-existing inclination. For many people, this slogan might actually impede their progress down the more complicated path that leads to true satisfaction.

One of the interesting things I uncovered in my research was that the term “follow your passion” didn’t really emerge in the context of career advice until the 1980s. Where did it come from? I argued that two critical trends converged during this period.

First, the unionized industrial work that characterized mid-century American economic growth gave way to a less rooted knowledge sector. Workers who might have previously taken a job at whatever factory happened to be located in their hometown might now be forced to travel cross-country in search of a suitable office position.

For the first time, the question of what you wanted to do for a living became pervasive — a shift captured well by the emergence in the early 1970s of Richard Bolles’ seminal career guide, What Color is Your Parachute: one of the original books to help readers identify which professions suit their personality and interests. It’s important to remember that this was a radical notion. “[At the time,] the idea of doing a lot of pen-and-paper exercises in order to take control of your career was regarded as a dilettante’s exercise,” Bolles later explained.

The second force at play was Joseph Campbell, the polymath literature professor who was heavily influenced by Carl Jung, and popularized the hero’s journey as a foundational mythology that emerges in many cultures. In 1988, PBS aired a multi-part interview with Campbell hosted by Bill Moyers. This wildly popular series introduced the concept of following your bliss, which Campbell, who read Sanskrit, had adapted from the ancient Hindu notion of ananda, or rapture.

Combine these two forces — a sudden need to figure out what you wanted to do for a living with Campbell’s mantra — and a strange, secularized, bastardized hybrid emerges: the key to career happiness, we decided as the 80s gave way to the 90s, was to follow your passion.

I was reminded of this history as I recently began reading Stephen Cope’s engaging treatise, The Great Work of Your Life (hat tip to Brett McKay). In this book, Cope dives deep into the classic Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, which tackles the centrality of ananda, and was almost certainly an influence on Campbell’s blissful bromide.

Cope notes that this text indeed argues for the importance of discovering one’s dharma (calling), and giving it full commitment. What caught my attention, however, was the complexity Cope ascribes to this notion. In the ancient context in which the Bhagavad Gita was first composed, dharma was not something you identified through soul searching about what really lights your fire. As Cope writes:

“In the caste system of ancient India, dharmas were prescribed at birth. Arjuna [one of the two main characters of the Gita] was born into the warrior class. So, he was destined to be a warrior. It was his sacred duty to fight a just war. He never had any choice in the matter, nor was his dharma based on any particular personal qualities.”

As Cope then elaborates, in the traditional culture where this story was told, the very concept of an autonomous “personal self” didn’t exist.

This idea of dharma — or its equivalent — manifesting as a burden or responsibility that one takes on, not an energizing inclination, is common in the many cultural interpretations of the hero’s journey monomyth. Ancient wisdom, in other words, doesn’t so much prescribe that we follow our passion, as it does that we approach with passion the trials and responsibilities placed before us.

Modern career advice may be based on an incomplete translation of the underlying philosophies that sparked its emergence four decades earlier. For many, recognizing this reality is empowering. The belief that the world owes you the perfect role for your special unique personality is myopically self-focused and ill-suited to hard times. The alternative notion that the world needs you to offer all that you can is comparably liberating.

June 8, 2020

Answering Your Questions

In the early years of this blog, one of my favorite activities was answering reader questions. I used to put aside an hour almost every day for keeping up with these emails. Over time, however, the number of queries became too large to manage.

It occurred to me recently that the podcast format might provide a way for me to return to these roots while reaching many more people with my answers than what’s possible with one-on-one messages.

So this is what I did…

My new podcast, Deep Questions with Cal Newport, is currently available on Apple and Spotify (and soon to be available on other platforms as well).

The format is simple, I answer reader questions about the main topics we discuss here: work, technology, and the deep life. I do my best to avoid rants (spoiler alert: I usually fail).

I’ve released two episode so far (see above for the most recent episode), with a new one on its way. My plan this summer is to test out a season of the podcast between now and August: releasing a new episode roughly each week.

I’m soliciting these questions from my mailing list, so if you want to contribute, sign up for my list using the widget on the blog sidebar or on my homepage at calnewport.com.

And of course, if you like the podcast, leaving a review on your platform of choice helps spread the word…

#####

A Question of My Own: I’m trying to learn more about organizations that are having success working on police reform (eliminating abuse/brutality, improving community relationships, etc). If you know this field, and are willing to share some of your wisdom about which players seem to be efficacious, please send me a note at interesting@calnewport.com.

June 3, 2020

On Running an Office Like a Factory

I was recently browsing the archives of the MIT Sloan Management Review (as one does), when I came across a fascinating article from the Fall 2018 issue titled “Breaking Logjams in Knowledge Work.”

The piece starts with a blunt observation: “If you work in an organization, you know what it’s like to have too much to do and not enough resources to do it.”

This is not accidental:

“…many leaders continue to believe that their organizations thrive when overloaded, often both creating pressure and rewarding those who deliver under duress. It’s a popular but pathological approach to management.”

The knowledge sector, it turns out, wasn’t the first to deal with a misguided commitment to overload.

“U.S. manufacturers suffered mightily under this approach for decades,” the article’s authors write, “until many found a better way.”

In the 1980s, American factory managers believed that keeping every machine and worker perpetually busy was the key to productivity: “If everybody was busy, the thinking went, the plant would produce more.”

But then more advanced manufacturing techniques, originating in Japan, spread to American factories and replaced a simplistic commitment to busyness with a much more flexible and efficient approach to production.

Though the details of modern advanced manufacturing techniques are complicated (just ask any “six sigma blackbelt”), the authors claim that some of the basic ideas from this sector can be translated to the office setting to solve the problem of chronic overload and help everyone work more productively.

In particular, they focus on the crucial shift from push to pull.

A traditional way to build things is with a push system in which you move something along a production process to the next step as soon as you’re done with it. There are two problems with this approach:

It creates bottlenecks as certain steps in the process inevitably receive more work than they can handle, eventually slowing down everything else.

It complicates prioritization by distributing these decisions to the individual places where bottlenecks arise, leading to a jumbled approach that often doesn’t synchronize neatly, further delaying production.

The manufacturing sector eventually realized there were great advantages to instead move to a pull system in which you pull work to your step in the process only when you’re ready for it. This approach eliminates local bottlenecks because you don’t take on work you’re not ready to handle. In addition, because backups are now concentrated at the beginning of the process, it simplifies the task of prioritizing efforts, as these decisions can be made up front in a more systematic fashion.

Factories that deployed a pull model ended up functioning more productively. The authors of this article argue that this model can deliver similarly positive results to office settings.

The specific case study they present concerned research and development at MIT’s Broad Institute. Before their intervention, Broad implicitly followed a push model in which ideas were haphazardly pursued and bottlenecks were common:

“When knowledge work processes are managed via push, it’s difficult to track tasks in process because so many of them reside in individual email in-boxes, project files, and to-do lists. Complicating matters, talented employees — particularly those in innovation-focused environments — have a knack for continually pushing more new ideas into an organization than it’s equipped to process”

To switch to a pull model, the R&D group mounted on the wall a flow chart that captured the steps required to move an idea from conception to deployment. They then represented projects as post-it notes on this flowchart, affixed to their current step in the process.

This visual tool made it simple to enforce limits on works in progress at each step by having projects be pulled from one step to the next, preventing overload. This shift made a big difference:

“The exercise led to two insights. First, there was an obvious lack of common prioritization: Nobody was aware of every project, there was little consensus about which ones mattered most, and many projects overlapped or competed with others. Second, the system had too much work in process. Comparing the number of current projects with recent delivery history showed that employees had at least twice as much work as they could complete in the best of circumstances.”

By implementing a pull system that made all of the ongoing work transparent, and placing limits on work in progress, the Broad Institute was able to significantly improve the efficiency with which they completed projects.

This shift from push to pull is just one idea among many that could help make better sense of the chaos that defines modern knowledge work. As I argued recently, the time has come to start seeking these ideas. We can no longer allow the efforts in this sector to unfold as a haphazard cascade of email messages and hastily organized Zoom calls. We need to take seriously not just how much we work, but how this work is organized.

May 26, 2020

Can Remote Work Be Fixed? My Latest Article For The New Yorker

Earlier today, I published my latest article for the New Yorker. It’s titled: Can Remote Work Be Fixed?

In this semi-epic long-form essay, I dive into the history of the remote work movement, documenting why, after decades of excitement, it ended up falling short of its potential.

I then tackle the big question on a lot of peoples’ mind at the moment: Now that all knowledge workers are forced to work remotely, will we manage to fix these issues? Now that it’s urgent, in other words, can we make remote work actually work?

As you’ll discover, I find some room for optimism. Drawing lessons from the analogous history of the introduction of the electric dynamo to early 20th-century factories (this is a New Yorker article, after all), I argue that the pandemic might end up a forcing function that solves many — though certainly not all — of the issues that arrested remote work’s original rise.

Ultimately, even after we return to a modified normal with more people once again working in offices, these fixes will continue to pay dividends. As I write:

“Before the pandemic, we were already suffering through a productivity crisis, in which we seemed to be working longer hours, glued to screens and drowning in e-mails. The solutions that make remote work sustainable—more structure and clarity, less haphazardness—may also help fix these other long-standing problems in knowledge work. Work that is remote-friendly for some may be better work for all.”

Anyway, you’ll have to read the whole piece to get the details. I have no doubt that fans of the type of stuff we discuss here will find a lot to like in it…

May 22, 2020

The Lost Satisfactions of Manual Competence

Chris Anderson opens his 2012 book, Makers, with a story about his maternal grandfather, Fred Hauser. Anderson recalls a childhood experience spending a summer with his grandfather at his bungalow in the Westwood neighborhood of Los Angeles.

“He announced that we would be making a four-stroke gasoline engine and that he had ordered a kit we could build together,” Anderson writes. Familiar with constructing models, Anderson assumed that the box containing the kit would be filled with numerous numbered parts and assembly instructions. “Instead, there were three big blocks of metal and a crudely cast engine casting. And a large blue-print, a single sheet folded many times.”

As Anderson recalls, his grandfather deployed the standard hobby machinist equipment kept in his garage — “a drill press, a band saw, a jig saw, grinders, and, most important, a full-size metal lathe” — to slowly extract and polish from the blocks the many pieces that ultimately fit together into a functioning engine. “We had conjured a precision machine from a lump of metal. We were a mini-factory, and we could make anything.”

There’s great fulfillment in applying skill to slowly create something useful that didn’t previously exist — a reaction that’s likely embedded in our genes as a lost nudge toward survival-enhancing paleolithic productivity. Matt Crawford perhaps summarizes this reality best in Shop Class as Soulcraft, when he writes: “The satisfactions of manifesting oneself concretely in the world through manual competence have been known to make a man quiet and easy.”

And then we consider our current moment.

For most “non-essential” workers, the past two months have delivered a professional experience that’s exactly the opposite of Fred Hauser running a metal lathe in his California garage. Instead of manifesting ourselves concretely in the world, we endlessly pass digital messages back and forth, taking breaks only to talk to each other about these messages over cramped video conference screens.

Before the pandemic, the ritual of traveling to a physical office helped obfuscate the disembodied nature of most knowledge work. But when this element was stripped away, the intrinsic abstraction of our efforts became impossible to miss. Fred Hauser ended his spring with a working four-stroke engine. We’ll end ours with an email inbox fuller than when we began.

This observation matters because as many consider a deep reset in response to recent events, work has emerged as an important topic.

There’s something uniquely misery-making about days spent in a Makework Matrix of ceaseless digital communication that doesn’t seem to generate much beyond additional digital communication — we’re simply not wired for this as a species. Not surprisingly, I’ve received an increasing number of messages from Office Space Neos, tumbled into a state of introspection by the disruption of the lockdowns, and now wondering if they can tolerate this digitized busyness for the decades that remain before their retirement.

I don’t have a comprehensive answer to offer at the moment, but here are a few thoughts that come to mind about the responses to this reality we might see in the months and years ahead:

More solo entrepreneurs and freelancers experimenting with radical work setups that prioritize focused craft and minimize the digital ephemera that they were told was critical to crushing it, but might instead be crushing their soul.

A shift in entrepreneurial circles aways from digital endeavors — apps, content production — and toward small-batch physical manufacturing (Anderson’s book offers a useful survey of this general shift; a good specific case study is my friend Forest Prichard’s recent book on starting a farm.)

Hopefully: larger knowledge work organizations will also finally start taking workflow seriously; moving away from communication free-for-alls that turn everyone into a mix of human network routers and glorified administrative assistants, and toward more structured and focused work (stay tuned on this: I have a big new book on this particular topic coming out next year).

In the meantime, our current pause presents a good opportunity to think critically about what “work” means to you now, and what it could mean in a reset life. Or at the very least, give you a push to dust off the metal lathe in the back of your garage.

May 19, 2020

Let Go to Grow: On a Blogger’s Decision to Trade Social Media for a Quieter Life

A reader recently pointed me toward an interesting essay. It was written by a blogger and podcaster named Mika. “I’ve thought about how to start this post FOR MONTHS,” she begins, before building to her reveal:

“When I hear my instincts from my heart, I have learned that it serves me well to listen.

So one day, when I felt a thud in my heart that said “Let social media go” – I paid attention. And then it came again, and again, and again. “Let it go.” I started to question it and ask why I was feeling this. So towards the end of last year, I started questioning the role of social media in my life, comparing and contrasting the pros and cons of it. I’ve even taken breaks before so I thought about those times, too. Then it pretty much dawned on me as the following words were impressed upon me in a real, gut-punching kind of way:

We were not made for this.

I have tears in my eyes just now typing that.”

It’s not that Mika hated social media; she notes that it allowed her to interact with “truly awesome, good-hearted people,” and has helped her “achieve professional goals.” The problem is that it always demanded more:

“It’s endless opportunities of things I can do, share, say, discuss. It’s also an endless source of people I can serve in some way. It never turns off, the possibilities are infinite, and it just keeps going – and so does my mind and energy.”

One of Mika’s revelations during the past two months spent in lockdown was the degree to which “living a quieter, less hectic, more inwardly-focused life” resonated. She wanted to make this minimalist embrace of less permanent. But social media made that stillness impossible for her.

So she stopped using it. (“A blogger who is not on Instagram?? What’s the point?”, she jokes. My response: “Welcome to the club! You just doubled its size.”)

Mika is one of several stories I’ve heard recently about a pandemic-induced departure from social media. A commitment to simplicity and presence is a key component to many peoples’ deep reset, and social media can prove a stubborn obstacle to achieving this goal. This reality highlights one of the trickiest aspects of cultivating a deep life: it’s not just about eliminating bad things; sometimes it’s also necessary to remove the merely good to gain better access to the great.

A concept that Mika summarizes towards the end of her essay with a simple phrase that helped guide her through this transition: “let go to grow.”

#####

I’m always interested in stories of people taking dramatic steps to cultivate a deeper life. Feel free to share at author@calnewport.com. Relevant pictures are welcome.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers