Cal Newport's Blog, page 14

March 1, 2021

Email is Making Us Miserable

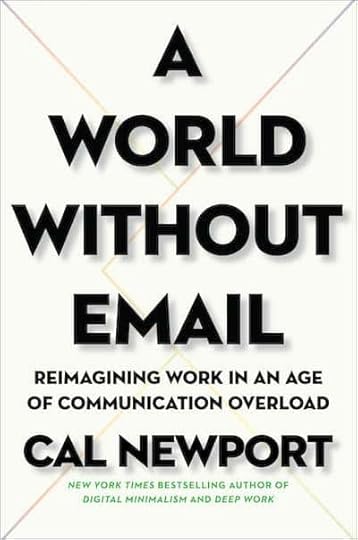

On Friday, the New Yorker ran an excerpt from the second chapter of my new book, A World Without Email. This chapter focuses on an aspect of the email revolution that’s often overlooked in our discussion of this tool: the ways in which it makes us miserable.

I open the piece by reviewing studies that quantify what many of us have learned through personal experience, which is that the more time we spend emailing, the less happy and more stressed we become.

As I then elaborate:

“Given these stakes, it’s all the more surprising that we spend so little time trying to understand the source of this discontent. Many in the business community tend to dismiss the psychological toll from e-mail as an incidental side effect caused by bad in-box habits or a weak constitution. I’ve come to believe, however, that much deeper forces are at play in generating our mismatch with this tool, including some that get at the very core of what drives us as humans.”

These deeper forces include a fundamental mismatch between the social circuits etched in our brains through evolution and the artificial communication environment cultivated by email. As I detail, our brains take one-on-one interaction extremely seriously, as maintaining strong tribal bonds was critical to Paleolithic survival.

Email, by contrast, creates a setting in which these conversations arrive faster than we can keep up, as demonstrated by our ever-growing inboxes. To our ancient social circuits this is an emergency, leading to a gnawing sense of impending, amorphous danger.

You can, of course, tell yourself that emails are not life and death, but according to research I cite, it’s hard to convince the rest of your brain that this is really true:

“When you skip a meal, telling your rumbling stomach that food is coming later in the day, and therefore that it has no reason to fear starvation, doesn’t alleviate the powerful sensation of hunger. Similarly, explaining to your brain that the neglected interactions reflected by your overfilled in-box have little to do with the health of your relationships doesn’t seem to prevent a corresponding sense of background anxiety.”

We shouldn’t ignore the psychological impacts of the way we work. A successful professional environment is one in which not only do we get things done, but we’re able to do so in a manner that’s sustainable to the human brains involved.

“We’re miserable,” I conclude, “because we’ve accidentally deployed a literally inhumane way to collaborate.”

The solution here is clear, we have to build specific alternatives to the hyperactive hive mind workflow that conquered the knowledge sector once tools like email and Slack arrived.

Now if only someone had written a whole book about what that might look like…

#####

Speaking of A World Without Email, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention one more time that if you order the book today (Monday) or tomorrow (Tuesday), you’ll gain access to my Email Academy video series that walks you through how to put the main ideas of the book into immediate action (see here for details on how to register your order). We even made the video clips sharable, so you can use them to try to convert your colleagues into a more enlightened way to work.

More importantly, of course, these early orders really help a book gain momentum, so the even larger “bonus” here is my sincere thanks.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

February 24, 2021

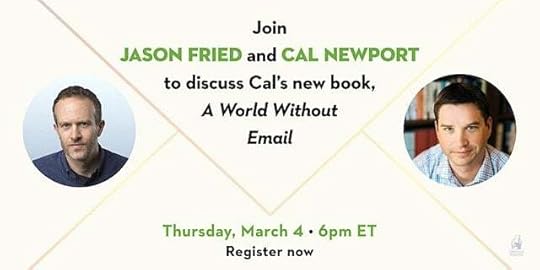

Jason Fried and I Explore A World Without Email

Jason Fried is one my favorite thinkers about workplace innovation. Basecamp, the company he co-founded, has been an inspiring incubator for knowledge work experimentation, from reduced work weeks, to office hours, to remote work, to the development of custom-built communication tools. Fried has documented these ideas in the bestselling books he co-authored, including Rework and (the suddenly timely) Remote, and on the famed Signal v. Noise blog. I featured Jason in Deep Work, and he’s featured again in A World Without Email.

Which all underscores my excitement to announce that to celebrate the launch of my new book, A World Without Email, the Politics and Prose bookstore here in Washington DC will be hosting a live virtual conversation between me and Jason at 6:00pm ET on March 4th.

Tickets are free but you have to register in advance here.

We will be discussing our current moment of overload and what might be required to solve it. We’ll dive deeper into my book, learn from Jason’s real world experiments, and even get into some friendly debates on the areas where our visions’ differ. Should be an exciting conversation.

To help support Politics and Prose, if you order A World Without Email directly from their store, you can get a copy signed by me (while supplies last). Details are on the event registration page.

A Request for HelpI would also be remiss if I didn’t remind you of the pre-order campaign I’m currently running. If you pre-order a copy of the book (in any format, from any retailer) by March 2nd, and register it here, you’ll be immediately sent a long excerpt from the book and access to the Email Academy video series I recorded exclusively to thank my longtime readers for supporting this title.

(Putting aside the “bonuses” for a moment, the main reason I’m emphasizing pre-orders is that it really helps the book launch by indicating to book buyers, bestseller lists, etc., that there are people out there who are interested in these types of ideas. So you have my deep personal appreciation as well if you’re willing to help out in this way.)

You can find out more about the pre-order campaign here…

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.February 21, 2021

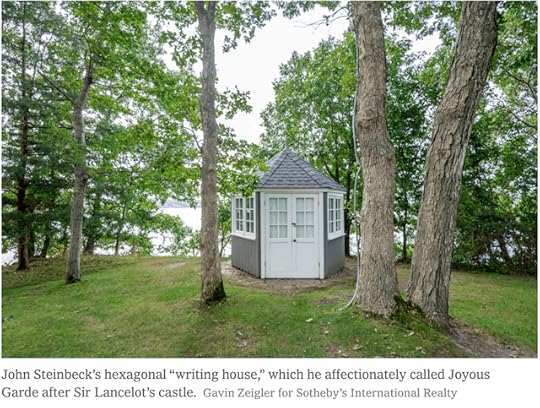

Steinbeck’s Productive Inactivity

Good news: if you have $17.9 million available, John Steinbeck’s 1.8 acre waterfront retreat is now for sale. It’s tucked onto a grassy peninsula in Upper Sag Harbor Cove, and features a pool, a long pier, and two cozy guest cottages. Arguably most important is the hexagonal, 100-square-foot “writer’s house” overlooking the water.

Encountering this real estate listing sent me down a brief but entertaining Steinbeck-at-Sag-Harbor rabbit hole. He bought the house in 1955, I discovered, 16 years after The Grapes of Wrath. He subsequently split his time between his apartment on the Upper East Side and his Sag Harbor retreat, which he inhabited mainly in the summer, and eventually dubbed “my little fishing place.”

Steinbeck would write in the morning, often in his waterside hexagonal shed, but as revealed in letters, he’d sometimes instead escape out into the harbor in his fishing boat. “I can move out and anchor and have a little table and yellow pad and some pencils,” he wrote a friend. “Nothing else can intervene.”

With his writing done, Steinbeck would then relax:

“Afternoons were spent fishing or hobnobbing at Sal and Joes or Baron’s Cove resort, or with Truman Capote, Kurt Vonnegut, and other writers at The Black Buoy, his beloved standard poodle in tow.”

Another source talked of how he would wander over to the docks in rubber boots to chat up the local fishermen.

Though it’s easy to be distracted by the more gaudy elements of Steinbeck’s summers, like his deep work on an anchored boat, it’s actually these final details — the languid afternoons — that stuck with me. Steinbeck represents the tail end of a period during which many intellectual types embraced a sort of heroic inactivity. They understood overload to be the foe of inspiration, and put their non-professional lives into an uneasy but necessary alliance with productive output.

It’s hard during our current moment of Zoom-schooled pandemic overwhelm to imagine anything more distant than the hard-drinking, free-flowing, Parisian idleness of the Lost Generation, but their underlying suspicion of busyness is worth highlighting. We shouldn’t strive to literally replicate Steinbeck’s summer lifestyle — though, admittedly, there have been more than a few times in recent months when day drinking at The Black Buoy seems just about right — as it’s ensconced in its own cultural moment. I don’t imagine, for example, Steinbeck ever worried about interrupting his conversations with Truman Capote to take his kid to urgent care.

But in these specific rhythms is a metaphor for something more generally true.

Steinbeck was “productive” in any practical sense of the word: he wrote 33 books and won a Nobel Prize for his efforts. But he wasn’t busy. In our current moment, by contrast, ambition is intertwined with overload — as if aspirations can only be alchemized in the heat generated by frenetic, hyper-connected digital motion.

An afternoon spent admiring Steinbeck’s little fishing place hints that we might not have this quite right.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

February 10, 2021

Announcing The Email Academy

My new book, A World Without Email, which comes out on March 2nd, is available for pre-order.

For multiple reasons, pre-orders are much more useful than normal sales, so if you were already thinking about buying my new book, I want to humbly nudge you toward considering a pre-order.

To demonstrate my sincere thanks to those who take the time to help my book in this manner, I wanted to put together the coolest possible incentive. This is how I came up with the idea of creating a brand new online course, available only to readers who pre-order the book, that features me breaking down the main ideas of the book and giving concrete advice on how to put them into action.

I call this course The Email Academy. It features a collection of short video lessons, taught by me, that summarize the big ideas of my book, and then walk you through a step-by-step game plan for putting the ideas into action right away.

The game plan I outline lasts two weeks and aims to immediately reduce the amount of email you receive by 50%, with even bigger reductions to follow. I further break out and customize the advice for employees, small business owner/team leaders, and executives of bigger organizations.

The game plan I outline lasts two weeks and aims to immediately reduce the amount of email you receive by 50%, with even bigger reductions to follow. I further break out and customize the advice for employees, small business owner/team leaders, and executives of bigger organizations.

I’m making this course available only to people who pre-order the book. On registering your pre-order using the form below, you will be given the website address and special access code needed to access The Email Academy starting March 2nd.

To further thank you for your purchase, you’ll also be immediately given a long excerpt from the book that outlines the main ideas, allowing you to get started moving toward a world without email while waiting for your copy of the book to arrive in March.

Instructions for Accessing these BonusesStep #1: Pre-Order the Book.

If you live in the US, you can pre-order from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or a local bookstore (as well as many other retailers). If you live in the UK, you can pre-order the UK edition at Amazon UK. (The book is also being translated into many other languages, but these will come out later.)

All formats of the book qualify for the pre-order promotion, though all things being equal, buying the physical book is the most helpful.

Step #2: Register Your Pre-Order.

Fill in your contact information and order number from your digital receipt using THIS FORM. Once your order has been verified, you’ll be provided access to a PDF that contains the information you need to access The Email Academy (starting March 2nd) and the bonus excerpt from the book.

(Questions or technical issues can be sent to CalNewport@penguinrandomhouse.com.)

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.February 4, 2021

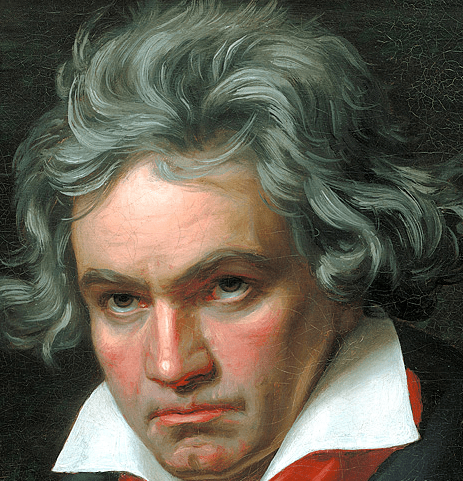

On Beethoven and the Gifts of Silence

Writing in 1801, at the age of 30, Ludwig van Beethoven complained about his diminishing hearing: “from a distance I do not hear the high notes of the instruments and the singers’ voices.”

As Arthur C. Brooks recounts in a 2019 op-ed, published in the Washington Post, Beethoven “raged” against his decline, insisting on performing, pounding pianos to ruin in a futile attempt to hear his own notes. By the age 45, he was completely deaf. He considered suicide, one friend reported, but was held back only by the force of “moral rectitude.”

It’s here that Beethoven’s story veers toward legend. Cut off from the world of sound around him, working only with musical structures dancing through his imagination, at times holding a pencil in his mouth against his piano’s soundboard to feel the consonance of his chords, Beethoven produced the best music of his career, culminating in his incomparable Ninth Symphony, a composition so daringly new that it reinvented classical musical altogether.

“It seems a mystery that Beethoven became more original and brilliant as a composer in inverse proportion to his ability to hear,” writes Brooks. “But maybe it isn’t so surprising.”

As Brooks elaborates, Beethoven’s diminished hearing limited the influence of “prevailing compositional fashions.” Whereas his earlier work was “pleasantly reminiscent” of his instructor, Josef Haydn, his later work was spectacularly innovative. “Deafness freed Beethoven as a composer because he no longer had society’s soundtrack in his ears.”

There are multiple lessons lurking in this tale. In his op-ed, Brooks argues that Beethoven teaches us about the rewards that can be cultivated in response to loss; an important message, to be sure.

What struck me, however, was the degree to which silence paradoxically allowed Beethoven to hear something new.

In our current techno-cultural moment, we’re constantly connected to a humming online hive mind of takes and urgency and quantified influence. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told I was missing out because of my absence from this scrum. I needed to “build my brand,” or be exposed to more interesting people and important ideas, or plugged into the tick tock of the big events of the day.

But it’s also clear to me that much of my deepest work came from periods of relative disconnection; when I was living a life defined largely by the demands of my young family, a big stack of books, a deep leather chair, a few hours a week in front of new students on an old university campus, and endless miles walking and thinking — often in the woods.

Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls overlooking palm trees in sleepy Key West. Lincoln pondered the Emancipation Proclamation amidst the relative peace of the Old Soldiers’ Home. Rowling completed the Harry Potter epic ensconced in the opulent quiet of the Balmoral Hotel.

Sometimes, it seems, there’s long term advantage in removing “society’s soundtrack” from your ears, even if in the moment the absence is acute. As Beethoven so vividly demonstrates, you can’t really hear yourself until you’re able to turn down the volume on everyone else.

(Hat tip to Fabrice for sending me the Brooks column.)

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

January 26, 2021

Michael Lewis Doesn’t “Do” Social Media

Last May, Tim Ferriss interviewed the writer Michael Lewis. Early in the episode, Lewis said that people often describe him as “one of the happiest people they know.” Toward the end, we encounter one of the reasons why this is true.

As the podcast wraps up, Ferriss asks the standard question: “are there any other websites, or any other resources, social media handles, anything you would like to mention if people want to learn more about what you are up to?”

Lewis’s response is refreshing:

“I wish I could say ‘yes,’ but I don’t do social media. So the answer is ‘no’…I have no way to be found. Except through my work.”

The formula here is so simple that it’s easy to overlook: Do less, do what you do better, don’t get distracted along the way. But its value shouldn’t be ignored.

#####

Speaking of living deeply, due to popular demand, Scott Young and I are opening up a new session of our online course Life of Focus. If you want to find out more about the new session, sign up for the waiting list. Next week, Scott will be publishing to this list a series of articles on what we learned from the first session of the course, which we ran this fall, and was a great success (not to mention a lot of fun) .

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

January 21, 2021

David Mellinkoff’s Productive Lack of Productivity

A reader recently pointed me toward the 1999 obituary of the respected legal scholar David Mellinkoff. He flagged, in particular, this passage:

“After the war, David developed a successful law practice in Beverly Hills. He early discovered, however, that, in his words, “the law thrived on gobbledygook.” He wanted to learn how this had happened, but after searching for answers in standard sources, he concluded, ‘there wasn’t a single book that wove it all together.’ David decided to write that book. He closed his law office, sold his house, and moved to the woods of Marin County. Seven years later he published The Language of the Law (1963), the book by which he will be chiefly remembered.”

In 1956, at the moment when Mellinkoff decided to retreat into the woods, his decision to trade all the busyness, urgency, and, of course, remuneration of running a Beverly Hills law firm for the monasticism of Marin must have seemed shockingly unproductive. And yet, when considered through the distance of history, Mellinkoff’s nurturing of what became The Language of the Law becomes self-evidently the most productive use of his talents.

I don’t think everyone should retreat to a quiet cabin. Probably most people would find such a commitment to intellectual minimalism intolerable. But I’m convinced that this option should be more common, especially among those with Melinkoff’s cognitive gifts. When you expand the time horizon for what you mean by “productive,” the options for crafting a deep life similarly expand.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

January 11, 2021

A World Without Email

I’m pleased to officially announce my new book: A World Without Email: Reimagining Work in an Age of Communication Overload. It comes out March 2nd in the US (and March 4th in the UK).

I started working on this book in 2016, almost immediately after Deep Work was released. At some point, I put the manuscript on pause to write Digital Minimalism, then returned my attention to grappling with its central ideas.

In many ways, this book is my magnum opus on the topic of technology and the workplace. If you’ve been following my articles for the New Yorker over the past year or so, or listening to my podcast, you’ve encountered a sampling of the rigorous new thinking at the core of this effort.

I’ve divided A World Without Email into two parts.

The first part, which is titled “The Case Against Email,” provides the definitive treatment on how the world of work transformed after the introduction of digital communication tools, and what unintended consequences these changes created.The second part, which is titled “Principles for A World Without Email,” introduces a framework I call attention capital theory that can be deployed to radically rethink how we work, pushing us toward a vision in which ceaseless, ad hoc messaging is replaced with much more sustainable and structured approaches to producing valuable output with our brains.The advice in this book is designed to be relevant for several different audiences, including employees, entrepreneurs, and executives. This breadth is captured in the endorsements, which include:

Dropbox cofounder Drew Houston, who says “A World Without Email crystallizes what so many of us feel intuitively but haven’t been able to explain: the way we’re working isn’t working.”Kevin Kelly, who says “Cal Newport is on a quest to uncover better ways for knowledge workers to collaborate.”Harvard Business School Professor Leslie Perlow, who says “This book is a call to action”Greg McKeown, who calls the book ” bold, visionary, almost prophetic.”I will, of course, be talking about the book more as we approach the publication date. If you preorder the book, hold on to your email receipt, as I’ll be announcing soon a way for you to redeem it to receive a pre-order bonus.

But until then, I’m just excited to finally be talking publicly about something I’ve been working on for so long on my own…

#####

Speaking of my books: if you live in the UK, the kindle version of Digital Minimalism is currently on sale for only 0.99p…if you haven’t read my latest yet, this is the absolute best time to do so!

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.January 2, 2021

Projects vs. Tasks: A Critical Distinction in Productive Scheduling

In a recent episode of my podcast, an Australian doctor named Nathan asked an interesting question regarding some difficulties he had maintaining and organizing his task list:

“David Allen asked ‘Is it actionable?’; separating tasks from ideas. But I also find that there are different types of tasks. The easiest to deal with are what I’m taking to calling ‘concrete’ tasks, such as taking out the rubbish, or submitting a final report. These are defined, necessary tasks that are cognitively easy to deal with. However, I’m also aware of ‘aspirational’ tasks, such as ‘summarize War and Peace,’ which are open-ended, and don’t really matter if you accomplish them by a specific time…they tend to just pile up.”

This is an important question because it touches on the rare productivity topic that’s both crucial to my personal process, and something that I haven’t already written much about. I thought, therefore, it would useful to briefly review the answer I gave Nathan.

In the influential world of Getting Things Done (GTD), all work eventually reduces to specific and unambiguous “next actions,” an idea David Allen adapted from the business consultant Dean Acheson (unrelated to Truman’s Secretary of State). In GTD, you might have a list of broader “projects,” such as Nathan’s example of summarizing Tolstoy, but these are just reminders that should spur you to add relevant next actions to your task list during your next review; perhaps, in this case, “buy notebook for book summary,” or “read the next 10 pages.”

As I told Nathan, I do not strictly subscribe to this philosophy of task essentialism. For me, some projects are never translated into tasks. Instead, I place them on my quarterly plan. I’ll then see the project when setting up my weekly plan. At this point, I work out what progress, if any, I want to make on it during the upcoming week. Finally, I see these notes each day as I setup my time block schedule, leading me to allocate the specific minutes the project needs during the upcoming hours.

For the sake of example, let’s tackle how I might schedule Nathan’s War and Peace case study:

Description of the project in my Quarterly Plan: “One of my goals this winter is to finish reading War and Peace, while taking good notes on each chapter.”

Sample Weekly Plan note about this project: “Put aside 30 minutes for lunch each day this week, and work on War and Peace while eating. The one exception is Thursday, as I have a lunch scheduled with Diana.”

Sample time block schedule: Every day of the week, with the exception of Thursday, includes a 30-minute time block labeled “lunch + W&P.” When I get to that block, I know exactly what I need to be working on.

For projects that require an ambiguous but significant amount of deep work, this planning flow from quarterly to weekly to daily is how I ensure that the sheer volume of cognitive effort required to accomplish something hard actually occurs. If I instead simply added the equivalent of “read the next 10 pages” to an overflowing task list, I doubt I’d ever make much progress on the things that matter.

To be clear, most of the obligations on my plate exist as concrete items in my task lists (which, as my podcast listeners know, I maintain using Trello). But most of the projects that move the needle in my career — working on a research paper, writing a major article — never get discretized into bite-size actions on a list. I instead treat them with the level of intention that their formidable difficulty deserves.

This distinction between tasks and projects is subtle, but it’s also critical to how I think about my work, so I thought it was worth discussing as we enter a new year and begin pondering how to make the most out of this annual return to a proverbial clean slate.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

December 29, 2020

Theodore Roosevelt’s Focused Advice

One of my colleagues at Georgetown recently pointed me toward a 1902 letter that Theodore Roosevelt sent to his son Kermit, who at the time was at boarding school.

Here’s the passage that caught my attention:

“I am delighted at all the accounts I receive of how you are doing at Groton. You seem to be enjoying yourself and are getting on well. I need not tell you to do your best to cultivate ability for concentrating your thought on whatever work you are given to do—you will need it in Latin especially.”

As readers of Deep Work know, I’ve previously highlighted Teddy’s fabled powers of focus as playing a critical role in his rise, so it’s not surprising that he’s emphasizing this same skill to his son. What strikes me, however, is that this recommendation isn’t standard for all students.

The connection between concentration and effective thinking is well-understood by this point, and yet few curriculums, at any level of education, aim to help students cultivate this ability. I can think of few meta-skills more important in an increasingly symbolic and complex culture than the ability to lock in on an abstract challenge and see it through to a useful conclusion. But we rarely talk about what it actually feels like to think hard, and how to get better at it.

Teddy prefaced his letter to Kermit by saying “I need not tell you.” The implication being that his advice on concentration was well-worn. I’m not sure that it remains so obvious in our current moment.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9944 followers