Cal Newport's Blog, page 12

August 17, 2021

On the Pandemic and Career Downsizing

Earlier this summer, the Labor Department released a report that included a shocking statistic: close to 4 million people had quit or resigned in April. These numbers remained high in the spring months that followed. The business press began calling this workplace exodus the “Great Resignation.”

In my latest essay for the New Yorker, published earlier this week, I took a closer look at this trend. There are many different factors powering the Great Resignation, and it impacts many different demographics. Amidst this complexity there was one thread in particular that I pulled: highly-educated knowledge workers leaving their jobs not because the pandemic presented obstacles, but because it instead nudged them to rethink the role of work in their lives.

As I elaborate in the piece, I was able to find insight for this “career downsizing” trend in one of my favorite works of American philosophy, Thoreau’s Walden. This book is often misunderstood as an ode to simplicity and the beauty of nature. As I explain briefly in my essay, and in more detail in Digital Minimalism, it actually proposes a radical economic theory that demands that the value of existence be weighed against inanimate acquisitions — a rebalancing aided by disruption of the type Thoreau induced when he temporarily relocated to the woods outside his home town.

This trend toward career downsizing, in other words, may be explained in part by an entire class of workers being unexpectedly thrown into a “Zoom-equipped Walden Pond.”

I encourage you to read the entire essay if the topic interests you. But at the very least, as the Great Resignation either unfolds or resolves in the months ahead, this is a subplot worth monitoring.

#####

Addendum…

My new essay mentions my friend Brad Stulberg’s new book, The Practice of Groundedness, which I praise as follows on the book jacket: “A crucial alternative for those of us exhausted by soulless exhortations to crush it, and looking for a deeper approach to building a successful life.”

The book comes out September 7th. Click here to find out more about the book and the preorder bonuses Brad is offering those who order it early.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

August 12, 2021

A $5.5 Billion Reminder that Email is Not Work

Last winter, a risk analyst at Credit Suisse noticed that one of their clients, a hedge fund named Archegos, was light on collateral. As is common in this world of high finance, Credit Suisse had loaned Archegos money to buy stock. The value of Archegos’s position had come down and the bank’s models were saying that the bank either needed more collateral from the fund, or needed to push Archegos out of their position by calling in the loan.

So far, pretty normal stuff.

As detailed in a report on the incident, compiled by the law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LP, and released last month, the issue was what happened next.

The analyst at Credit Suisse and the accounting manager at Archegos fell into a communication rhythm all too common in our current age of the hyperactive hive mind. The analyst asked to setup a meeting with the manager. The manager replied, in effect, “I’m busy, let’s try tomorrow.” The next day, he said to just send over a proposal. A week and a half pass before the analyst asks for “thoughts” on the proposal. The manager said “he hadn’t had a chance to look at it yet” but would try to get into it “today or tomorrow.”

Then the stock prices fell more. Archegos’s position collapsed. Without the extra collateral, Credit Suisse lost $5.5 billion.

As Bloomberg’s Matt Levine explains in a recent column on the debacle, what makes this case intriguing is that there is not “some fancy finance thing that went wrong,” nor is it a story of “individual stupidity or greed or recklessness.” As he summarizes:

“It’s just that they sort of kept each other in the loop as a substitute for actually doing anything. The processes were all moving along nicely, which gave everyone a false sense of security that they would produce the right result.”

I couldn’t think of a better case study for the illusory, performative pseudo-value generated by the hyperactive hive mind. The players in this story were for sure feeling very productive: furiously typing on devices, messages moving back and forth, bases being touched, plates spun, their industry palpable.

But the actual activity that mattered, the realization that they were short on collateral and urgently needed to reduce their investment exposure, was missed. Ad hoc, back-and-forth, unscheduled messaging kept everyone busy. But it didn’t actually work.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

July 21, 2021

On Pace and Productivity

One of the books I’m reading on vacation at the moment is John Gribbin’s magisterial tome, The Scientists. I’m only up to page 190 (which is to say, only up to Isaac Newton), but even early on I’ve become intrigued by a repeated observation: though the scientists profiled in Gribbin’s book are highly “productive” by any intuitive definition of this term, the daily pace of their work was incredibly slow by any modern standards of professional effectiveness.

Galileo probably had his famed insight about the period of a pendulum in 1584, while a medical student in Pisa, observing swinging chandeliers in the cathedral. He didn’t finish working out the details experimentally, however, until 1602.

He was occupied in the interim by numerous other endeavors, including the handling of debts he unexpectedly inherited from his father, Vincenzio, after his death in 1591, and the writing of a treatise on military fortifications, a topic of great interest to the Venetian Republic.

Critically, as Gribbin’s explains, during this period Galileo was also occupied in part by his success in “leading a full and happy life,” in which “he studied literature and poetry, attended the theatre regularly, and continued to play the lute to a high standard.” He was not, in other words, locked up, grinding away in relentless pursuit of results. Yet results are what he did ultimately produce.

During Newton’s tenure at Cambridge, to cite another example, the university was closed for multiple years at a time due to plague epidemics. Though Newton later claimed that his thinking on gravity was stimulated by a falling apple observed during these forced idyls, Gribbins argues that his main insights came later. These early enlightenment-era shutdowns really did likely shutdown a lot of the young professor’s work.

It wasn’t until 1680, after an extended detour into alchemy, that Newton was spurred by a letter from a colleague to work out a formal understanding of what became the inverse square law that governs gravity. It then took until 1684 before he got around to publishing a nine-page version of this argument. It was yet another three years before this thinking expanded into his epic Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, the most important book in the history of science.

Returning to my original insight, the message I extracted from these historical encounters is that when it comes to our understanding of productivity, timescale matters.

When viewed at the fast scale of days and weeks, the famed scientists in Gribbin’s book seem spectacularly unproductive. Years would pass during which little progress was made on epic theories. Even during periods of active work, it might take months for important letters to induce a reply, or for news of experiments to make it across a fractured Europe.

(Galileo famously ground the lens for his first telescope in only twenty-four hours, but this was after an entire summer of him trying to track down an elusive visitor to Italy who was rumored to know something about this then new technology.)

When we shift, however, to the slow scale of years, these same scientists suddenly become immensely productive.

This line of thinking is still embryonic, but I’m increasingly convinced that at the core of any useful understanding of slow productivity will be this distinction in timescale. No one remembers Newton’s lazy lockdowns, but his Principia achieved immortality.

We need some degree of the frenetic tools highlighted in modern productivity discourse to organize and manage the necessities of work and life. When it comes to pursuing deeper impact, however, perhaps sustainable success requires the embrace of a different and more forgiving timescale.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.July 16, 2021

On the Myth of Big Ideas

I recently came across an article in the New Yorker archives that I greatly enjoyed. It was written by a Dartmouth mathematics professor named Dan Rockmore, and is titled: “The Myth and Magic of Generating New Ideas.” The essay tackles a topic that’s both central to my professional academic life, and wildly misunderstood: what it takes to solve a proof.

To capture the reality of this act, Rockmore tells a story from when he was a young professor. He was working with his colleagues to try to find a more efficient method for solving a large class of wave equations. “We spent every day drawing on blackboards and chasing one wrong idea after another,” he writes. Frustrated, he left the session to go for a run on a tree-lined path. Then it happened.

“As I crested the last hill, I saw it all at once: the key to modifying the algorithm we’d been puzzling over was to flip it around, to run it backward. My hear started racing as I pictured the computational elements strung out in the new opposite order. I sprinted straight home to find a pencil and paper so I could confirm it.”

As Rockmore then elaborates, in popular portrayals of mathematical machinations, the focus is often on this final bit, the eureka moment while jogging through the woods, or John Nash surveying the crowded Princeton bar and figuring out non-cooperative game theory all at once.

But this moment cannot come without the days of frustration at the blackboard. “You can’t really blame the storytellers,” Rockmore writes, “It’s not so exciting to read ‘and then she studied some more.’ But this arduous, mundane work is a key part of the process.”

This absolutely matches my experience as a professional theoretical computer scientist. The top performers in my field are smart, to be sure, but their the real advantage is less some supercharged brain that delivers fully-formed proofs in effortless bursts, than it is a supercharged work ethic: an ability to stick with mastering hard results from the literature; building the mental frameworks, one arduous level after another, on which the eventual insights can then find purchase.

I don’t have a sweeping big think conclusion to draw from these observations. But it seems somehow vaguely true that in an increasingly cognitive world, understanding those who apply their brains at an elite level may end up a worthwhile endeavor.

#####

Administrative Note:

My longtime friends, The Minimalists, have a new book out this week! It’s titled: Love People, Use Things. Here’s my blurb from the back cover:

“Joshua and Ryan have penned an urgent manifesto for the growing movement away from the material and toward the meaningful. An important book for our current moment.”

A great companion to contemplations of living deeper. Check it out…

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.July 6, 2021

On Twitter Addiction and its Discontents

Earlier this week, Caitlin Flanagan published a provocative essay in the Atlantic titled: “You Really Need to Quit Twitter.” In this instance, the label of “provocative” seems obligatory, even though an objective read of the piece reveals mainly common sense. Which serves to underline the whole point Flanagan is attempting to make.

The article reports on the author’s 28-day break from Twitter after her relationship with the service had become increasingly fraught.

“My family’s attitude toward my habit has been…concerned, grossed out, or disappointed,” Flanagan writes. “My employer had given up and adopted a sort of ‘It’s your funeral’ approach.” She could no longer escape what had become obvious:

“I know I’m an addict because Twitter hacked itself so deep into my circuitry that it interrupted the very formation of my thoughts.”

So Flanagan asked her son to change her password. She signed a contract saying no matter how much she begged, he shouldn’t let her back into her account before the month had passed. She called it “Twitter rehab.”

Predictably, the experience was hard at points. Flanagan felt isolated and antsy. It was not the distraction or the breaking news information she missed, nor was it the ability to encounter interesting new people or ideas (in my experience, one of the most common themes of Twitter apologia), but instead the addict’s thrill of being part of something risky: inserting her take into the digital slipstream; sweating that loaded beat before learning if she’d be lauded or attacked.

She decided to try to convince her son to give her password back early. “I gave him a very rational description of Twitter’s important role in a journalistic career, and how it keeps one’s perspective fresh in readers’ minds,” she wrote. He handed her a William James book on habit formation.

On the positive side, Flanagan was surprised by how quickly she regained her once cherished ability to get lost in books. She had not previously accepted the degree to which the platform had inserted an uneasy restlessness into her attempts to read. The realization angered her:

“And that’s when I realized what those bastards in Silicon Valley had done to me. They’d wormed their way into my brain, found the thing that was more important to me than Twitter, and cut the connection.”

Life without Twitter felt different: “There was nothing to do except keep writing (freed from the story budget of Twitter, I actually had some interesting ideas) and keep reading.” It felt better.

As Flanagan notes, the simplest definition of an addiction “is a habit that you can’t quite quit, even though it poses obvious danger.” For many, Twitter has long since passed this threshold, but like Flanagan begging her son for her password back, we keep bargaining and explaining why it really is important.

Last I checked, Flanagan was still largely absent from Twitter, even though her 28-day rehab period has long since expired. Perhaps the real provocation is that committed displays of digital minimalism of this type remain so rare.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

June 30, 2021

Notes on Quentin Tarantino’s Writing Routine

About an hour into his recent interview on Joe Rogan’s podcast, Quentin Tarantino was asked about his writing habits.

“It all changed,” he revealed, “more or less around the writing of Inglorious Basterds.” Before starting work on the 2009 film, Tarantino described himself as “an amateur, mad little writer” who would work late at night, or by going to a restaurant, where he would “order some shit, and drink a lot of coffee, and be there for 4 hours with all my shit laid out.”

He decided he wanted a more “professional” routine. Here’s how he described it:

“I started writing during the day time. I get up, so you know, it’s 10:30, or 11:00 o’clock, or 11:30, and I sit down to write…Like a normal workday, I would sit down and I would write until 4, 5, 6, or 7. Somewhere around there, I would stop. And then, I have a pool, and I keep it heated, so it’s nice, so I go into it…and just kind of float around in the warm water and think about everything I’ve just written, how I can make it better, and what else can happen before the scene is over, and then a lot of shit would come to me, literally a lot of, a lot of things would come to me. Then I’d get out and make little notes on that, but not do it, and that would be my work for tomorrow.”

Here are three things that caught my attention about Tarantino’s routine…

First, notice how he leverages a return to a specific and notable setting — his heated pool — to help support creative insight. Like Darwin making a fixed number of circuits on his sandwalk each morning, the brain can learn to associate certain environments with certain modes of thought.

Second, notice how at the end of each deep work session he leaves in place a creative ramp to help speed up his entrance to the next day’s session. With elite-level cogitation, getting started can be daunting. Having well-developed notes waiting to direct your initial efforts diminishes this hurdle.

(Hemingway did something similar. As he explained in a 1935 Esquire interview: “The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next.”)

Third, and finally, notice how his ritual underscores the distinction between hard work and hard to do work. It is very hard in the long run to produce a screenplay at Tarantino’s level. But this reality does not necessarily require short term periods of frenzied, exhausting effort.

Tarantino writes, then floats, writes, then floats — a rhythm that’s tractable at the scale of any individual day. “This has become,” he explains, “this really nice, this really enjoyable, this really lovely way to write.”

But over time, it aggregates to yet another Oscar-worthy outcome.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

June 22, 2021

On the Dynamo and Email

In an article about remote work that I wrote for the New Yorker last year, I pointed to an underground classic research paper titled “The Dynamo and the Computer: An Historical Perspective on the Modern Productivity Paradox.” It was written by a Stanford economist named Paul David, and published in the American Economic Review in 1989.

In the article, David performs a close study of the adoption of electric dynamos in factories at the turn of the twentieth century. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s obvious that the right way to leverage electric power in factories is to put a small individual motor on each piece of equipment. As David points out, however, it took decades after the introduction of practical electrical generation before this obvious shift finally occurred.

As I summarized:

“[A]t the turn of the century, most factories were powered by massive central steam engines. The engines turned overhead shafts, which were connected by an intricate array of belts and pulleys to close-packed machinery. When electric motors were first introduced, factory owners tried to integrate them into their existing setups; often, they’d simply replace the hulking steam engine with a giant electric dynamo. This introduced some conveniences—no one had to shovel coal—but also created complexities. It was hard to keep all the electrical components working; many factory owners opted to stay with steam.”

I think this example is useful in orienting our thinking about the technological disruptions afflicting commerce in our current century.

The arrival of digital networks in the office is similar to the arrival of electrical power to factories. In both cases, the innovation is accompanied by a confident intuition that the very nature of how we work is poised for an irreversible shift toward a new, better configuration.

But as David’s paper underscores, these shifts can be slow to unfold. New technology is often a necessary but not sufficient precondition for revolution. The other ingredient is the uneven, frustrating work of changing the definition of “work” to accompany the new tool.

At the turn of the century, factories had all of the components needed to deploy the much more efficient individual motor approach to manufacturing. But it still took decades for them to actually make the shift away from hulking central power plants and overhead spinning shafts.

Today we almost certainly have all the technological tools needed to push knowledge work into its next productive phase shift. But we remain in the moment mired to instead simply moving unstructured interactions into email threads and Zoom meetings; the Digital Age equivalent of hooking up a new electric motor to the old belt drive system.

The solution is not to look to Silicon Valley and ask for better innovations. The needed technological innovations have already arrived in the form of Ethernet, email, and interactive HTML. Where we need to turn our attention is back toward our own proverbial factories and ask if there’s a better way to run our machines.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

June 16, 2021

Haruki Murakami and the Scarcity of Serious Thought

I recently returned to Haruki Murakami’s 2007 pseudo-memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. I first encountered this book back in 2009. It inspired me at the time to write an essay titled “On the Value of Hard Focus,” which laid the foundation on which I went on to build my theory of deep work. Which is all to say, Murakami’s short meditation on running and art holds a special place in my personal literary canon.

On my re-read, my attention was snagged by the following passage:

“Gradually, though, I found myself wanting to write a more substantial kind of novel. With the first two, Hear the Wind and Pinball, 1973, I basically enjoyed the process of writing, but there were parts I wasn’t too pleased with. With these first two novels I was only able to write in spurts, snatching bits of time here and there — a half hour here, an hour there — and because I was always tired and felt like I was competing against the clocks as I wrote, I was never able to concentrate. With this scattered approach I was able to write some interesting, fresh things, but the result was far from a complex or profound novel.”

Murakami wrote his first two novels late at night after closing down the bar he owned and ran near the Tokyo city center. These works were well-received: his first won a prize for new writers from a literary magazine, and his second also attracted positive reviews. But the effort both exhausted and frustrated him.

Murakami realized he was coasting on bursts of latent talent. He had caught the attention of the literary establishment because of inventive stretches in his prose, but he worried that if he kept producing these “instinctual novels,” he’d reach a dead end.

Against the advice of nearly everybody, he sold his bar, and moved to Narashino, a small town in the largely rural Chiba Prefecture. He began going to bed when it got dark and waking up with the first light. His only job was to sit at a desk each morning and write. His books became longer, more complex, more story driven. He discovered what became his signature style.

“My whole body thrilled at the thought of how wonderful — and how difficult — it is,” he recalled, “to be able to sit at my desk, not worrying about time, and concentrate on writing.”

Neither our economy nor the demands of a live well-lived dictate that everyone should aspire to be sitting alone at a desk in rural Narashino, crafting literature to the light of the rising sun. My growing concern, however, is that such real commitment to thought has become too rare.

It was only through this intellectual monasticism that a talent as large as Murakami was able to extract the works for which is so rightly now revered. And yet, outside of award-caliber novelists, a similar commitment to depth is alarmingly rare. Even the elite cognitive professions such as professors, lawyers, doctors, and journalists, for which the value of thought is clear and accepted, find themselves increasingly trying to slot these efforts into fragments of time sieged by unrelenting messages, and meetings, and news, and minutia.

This the moment of melancholy that hit me as I returned to this book earlier this week: Many of us in such jobs have become like the young Murakami, up late after closing the bar, frustrated that the metaphorical novels we’re crafting aren’t what they could be.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

June 4, 2021

Sebastian Junger’s Focused Retreat

In 1991, Sebastian Junger suddenly found himself with time to think. He had wounded himself with a chainsaw at his day job as a climber for a tree pruning company in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and was laid up recovering.

Morbidly inspired by the experience, Junger became interested in the idea of writing a book about dangerous jobs. In a tragic sense, his timing was good. That same year, a commercial fishing boat out of Gloucester named the Andrea Gail sunk off the coast of Nova Scotia in a historic storm. All six of her crew were lost.

Junger wrote a sample chapter about the Andrea Gail to include in a proposal for his dangerous jobs idea. It soon became clear, however, that the story of the lost fishing boat was rich enough to support an entire book on its own. The result was The Perfect Storm, which became an international bestseller after its release in 1997, and was subsequently adapted into a blockbuster movie staring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg. Junger was credited with reviving the adventure non-fiction genre. Some even called him a new Hemingway.

The twist of this story that perhaps interests me most, however, is what Junger did next: he bought a dilapidated house in the woods. To be more specific, in 2000, Junger purchased a rundown residence, built in the early 1800s, and hidden at the end of a winding, unpaved lane in Truro, a small town in upper Cape Cod known as a refuge for writers and artists.

As Junger explains in a 2019 interview with CapeCod.com, he spends as much time there throughout the year as possible: “It’s a very good place to to work. It’s old and removed from humanity.”

As he elaborates:

“It helps to be in a place mentally and physically where you can focus. Some people can do that in New York [where Junger has an apartment], and I can do that, too. But on the Cape, it’s easier to achieve that focus. The property that I have is really tucked away from other people and I can go for days without seeing or hearing another human being.”

This commitment to focus seems to have paid off, as Junger went on to win a National Magazine Award and an Oscar Nomination, become a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and publish five more acclaimed books, including his most recent, Freedom (which I recently read and quite enjoyed).

I couldn’t help but think about Junger’s hidden Cape Cod retreat when I browsed his Twitter feed earlier today. As might be expected, his timeline is thick with tweets from the past few months, promoting his new book. But if you scroll on it suddenly starts to bounce across long expanses of digital radio silence: a tweet on July 2019, then nothing until two tweets in April 2020, then silence again until February of this year.

Instagram is even sparser. Junger didn’t have an account on the platform until just a few months ago, and his feed contains only a collection of promotional images from the book, likely dumped en masse by a publicity assistant.

This online modesty isn’t really surprising. It’s hard, I imagine, to get lost in the superficial din of that glowing screen in your hand when outside your window is a quiet woods, only partially muffling the sound of crashing waves beyond. That’s the type of space that inspires one to instead orient their attention toward the deep and the slow.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.May 24, 2021

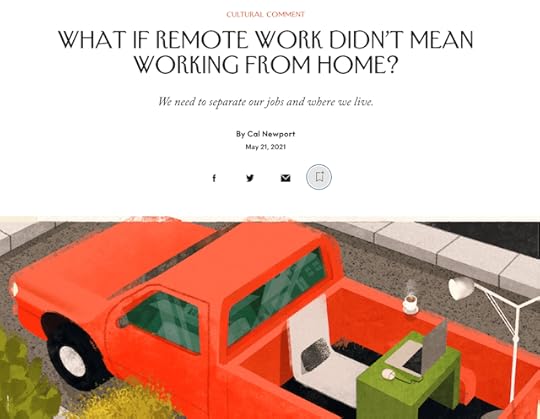

Thinking Outside the Home

Peter Benchley wrote Jaws in the backroom of the Pennington Furnace Supply, a short walk from his home in Pennington, New Jersey. Though he lived in a bucolic converted carriage house situated on nearly an acre of land, he preferred writing amidst the clamor of this industrial hideaway .

He’s not alone among authors in this retreat to an eccentric workspace near his home: Maya Angelou wrote in hotel rooms with all pictures removed from the walls; David McCullough toiled in a garden shed; John Steinbeck would bring a notebook and portable desk out on his fishing boat.

As I argue in my most recent essay for the New Yorker, published last week, these case studies are important to our current moment because, in some sense, writers are the original work-from-home knowledge workers. The fact, therefore, that they often go through so much trouble to avoid working in their actual homes might teach us something important about how to succeed with our post-pandemic shift toward permanently increased telecommuting. (Hint: perhaps subsidized work from near home needs to become a thing.)

I encourage you to read the full article to find out more about the lessons learned from these case studies (or, at the very least, to enjoy some gratuitous stories of the aspirational lives of famous authors).

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers