Cal Newport's Blog, page 9

August 1, 2022

TikTok’s Poison Pill

Just a few months ago, it seemed that the biggest social media news of the year would be Elon Musk’s flirtations with buying Twitter (see, for example, my article from May). Recently, however, a new story has sucked up an increasing amount of oxygen from this space: TikTok’s challenge to the legacy social platforms.

Last February, Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, released a quarterly report that revealed user growth had stalled. Analysts were quick to attribute this slow down, in part, to fierce competition from TikTok, which had recently blasted past the billion user mark. The valuation of Meta plummeted by over $200 billion in a single day.

Forced by investor pressure to respond, Meta began a sudden shift in its products’ features that moved them closer to the purified algorithmic distraction offered by its upstart rival. This spring, a leaked memo revealed Facebook’s plan to focus more on short videos and make recommendations “unconnected” to accounts that a user has already friended or followed. More recently, Instagram began experimenting with a TikTok-style full screen display, and has emphasized algorithmically-curated videos at the expense of photos shared by accounts the user follows.

From a short-term business perspective, these might seem like necessary changes. But as I argued in my most recent article for The New Yorker, published last week, the decision by companies like Facebook and Instagram to become more like TikTok could mark the beginning of their end.

The problem comes from their underlying business models. The social media giants of the last decade have cemented a pseudo-monopolistic position in the internet marketplace because they serve content based on massive social graphs, constructed in a distributed fashion by their users, one friend or follow request at a time. It’s too late now for a new service to build up a network of sufficient influence and complexity to compete with these legacy topologies.

TikTok, by contrast, doesn’t depend on this type of painstakingly accumulated social data. It instead deploys a simple but brutally effective machine learning loop onto the pool of all available videos on its platform. By observing the viewing behavior of individual users, this loop can quickly determine exactly which videos will most engage them; no friends, retweets, shares, or favorites required. The value of the TikTok experience is instead created by a unique dyadic mind meld between each user and the algorithm.

If platforms like Facebook and Instagram abandon their social graphs to pursue this cybernetic TikTok model, they’ll lose their competitive advantage. Subject, all at once, to the fierce competitive pressures of the mobile attention economy, it’s unclear whether they can survive without this protection.

As I argue in my article:

“This all points to a possible future in which social-media giants like Facebook may soon be past their long stretch of dominance. They’ll continue to chase new engagement models, leaving behind the protection of their social graphs, and in doing so eventually succumb to the new competitive pressures this introduces. TikTok, of course, is subject to these same pressures, so in this future it, too, will eventually fade. The app’s energetic embrace of shallowness makes it more likely, in the long term, to become the answer to a trivia question than a sustained cultural force. In the wake churned by these sinkings will arise new entertainments and new models for distraction, but also innovative new apps and methods for expression and interaction.”

In this prediction, I find optimism. If TikTok acts as the poison pill that finally cripples the digital dictators that for so long subjugated the web 2.0 revolution, we just might be left with more breathing room for smaller, more authentic, more human online engagements. “In the end, TikTok’s biggest legacy might be less about its current moment of world-conquering success, which will pass,” I conclude. “And more about how, by forcing social-media giants like Facebook to chase its model, it will end up liberating the social Internet.”

This future is far from guaranteed. But let’s hope it’s true…

The post TikTok’s Poison Pill first appeared on Cal Newport.July 11, 2022

LBJ’s Poolside Phone and the Connectivity Revolution

A reader named Peter recently sent me a perceptive note. He had just returned from a visit to Austin, where he had visited the LBJ Ranch, now operated as national historical site, located about 50 miles west of the city in the Texas Hill Country.

As Peter recalled, during the tour, the guide emphasized that as president, Lyndon Johnson was so obsessed with connectivity that he had a telephone installed beside his pool. “Everyone in the tour group laughed,” wrote Peter. But as he then correctly pointed out, this collective mirth may have been hasty.

In an age of smartphones, everyone has access to a phone by the pool. Also in the bathroom. And in the car. And in every store, and on every street, and basically every waking moment of their lives. The average teenager with a iPhone today is vastly more connected than the leader of the free world sixty years ago.

I thought this was a good reminder of the head-spinning speed with which the connectivity revolution entangled us in its whirlwind advance. We haven’t even begun to seriously consider the impact of these changes, or how us comparably slow-adapting humans must now adjust. Be wary of those who embrace our current moment as an optimal and natural evolution of our species’ relationship with technology. We still have a lot of work ahead of us to figure out what exactly we want. After sufficient reflection, it might even turn out that taking a call by the pool, LBJ style, isn’t as essential as we might have once imagined.

The post LBJ’s Poolside Phone and the Connectivity Revolution first appeared on Cal Newport.

July 5, 2022

The 3-Hour Fields Medal: A Slow Productivity Case Study

Earlier today, June Huh, a 39-year-old Princeton professor, was awarded the 2022 Fields Medal, one of the highest possible honors in mathematics, for his breakthrough work on geometric combinatorics.

As described in a recent profile of Huh, published in Quanta Magazine (and sent to me by several alert readers), Huh’s path to academic mathematics was meandering. He didn’t get serious about the subject until his final year at Seoul National University, when he enrolled in a class taught by Heisuke Hironaka, a charismatic Japanese mathematician who had himself won a Fields back in 1970.

Given his recent conversion to the mathematical arts, Huh was only accepted at one of the dozen graduate schools to which he applied. It didn’t take long, however, for him to stand out. As a beginning student, Huh managed to solve Read’s conjecture, a long-standing open problem concerning the coefficients of polynomial bounds on the chromatic number of graphs. The University of Michigan, which had previously rejected Huh’s graduate school application, soon recruited him as a transfer student. Along with his collaborators, Huh generalized the approach he innovated to tackle Read’s conjecture to prove similar properties for a much broader class of objects called matroids. The new result stunned the mathematics community. “It’s pretty remarkable that it works,” said Matthew Baker, a respected expert on the topic.

The reason so many readers sent me the Quanta profile of Huh, however, was not because of its descriptions of his mathematical genius, but instead because of the details it shares about how Huh structures his deep efforts:

“On any given day, Huh does about three hours of focused work. He might think about a math problem, or prepare to lecture a classroom of students, or schedule doctor’s appointments for his two sons. ‘Then I’m exhausted,’ he said. ‘Doing something that’s valuable, meaningful, creative’ — or a task that he doesn’t particularly want to do, like scheduling those appointments — ‘takes away a lot of your energy.'”

One of the core principles of my emerging philosophy of slow productivity is that busyness and exhaustion are often unrelated to the task of producing meaningful results. When zoomed in close, three hours of work per day seems painfully, almost artificially slow — an impossibly small amount of time to get things done. Zoom out to the larger scale of years, however, and suddenly June Huh emerges as one of the most, for lack of a better term, productive mathematical minds of his generation.

The post The 3-Hour Fields Medal: A Slow Productivity Case Study first appeared on Cal Newport.June 22, 2022

On Wendell Berry’s Move from NYU to a Riverside Cabin

In my previous essay, I wrote about how novelist Jack Carr rented a rustic cabin to help focus his attention on completing his latest James Reece thriller. This talk of writing retreats got me thinking again about what’s arguably my favorite example from this particular genre of aspirational day dreaming: Wendell Berry’s “camp” on the Kentucky River.

In February, Dorothy Wickenden, whose father Dan Wickenden was Berry’s original editor at Harcourt Brace, featured Berry’s camp in a lengthy New Yorker profile of the now 87-year old writer, farmer, and activist. Berry brought Wickenden to a twelve-by-sixteen foot one-room structure, raised on concrete pilings high on the sloped bank of the river, only on the condition that she not reveal its exact location.

In the summer of 1963, Berry, all of twenty-nine, and just a few years into a professorship at New York University, built the current cabin on the same site where his great-great-great grandfather, Ben Perry, one of the first settlers in the valley, had long ago erected a log house. Berry remembered the location from his childhood. As Wickenden explains, Berry returned that summer to build an escape where he could “write, read, and contemplate the legacies of his forebears, and what inheritance he might leave behind.”

What struck me as I returned to this story were the unremarked implications of its timing. Berry supposedly built the cabin in the summer of 1963, but didn’t announce his resignation from NYU and move to Kentucky until 1964. Though I can’t confirm these details, I like to imagine Berry returning to New York from his summer retreat, with the attraction of the deep contemplation available on the quiet shores of the Kentucky River gnawing at his attention, stirring something within — until, finally, he cracked, and decided it was time to move home.

Regardless of the details of Berry’s motivation, it’s hard, in hindsight to question the decision, as he ended up writing fifty-two books in that humble room, and becoming one of the twentieth century’s most influential voices on sustainability and rural living.

Sometimes we retreat to the proverbial cabin to support deep work already under way. Other times, we build the cabin first, and then let its charms convince us to get started.

The post On Wendell Berry’s Move from NYU to a Riverside Cabin first appeared on Cal Newport.June 6, 2022

Jack Carr’s Writing Cabin

Last spring, I wrote an essay for The New Yorker about a notable habit common to professional authors: their tendency to write in strange places. Even when they have beautifully-appointed home offices, a lot of authors will retreat to eccentric locations near their homes to ply their trade.

In my piece, for example, I talked about Maya Angelou writing on legal pads while propped up on her elbow on the bed in anonymous hotel rooms. Peter Benchley left his bucolic carriage house on a half-acre of land to work in the backroom of a furnace supply and repair shop, while John Steinbeck, perhaps pushing this concept to an extreme, would lug a portable desk onto an old fishing boat which he would drive out into the middle of Sag Harbor.

My argument was that authors like Angelou, Benchley, and Steinbeck weren’t seeking pleasing aesthetics or peace (furnace repair is loud). They were instead trying to escape cognitive capture. “The home is filled with the familiar,” I wrote, “and the familiar snares our attention, destabilizing the subtle neuronal dance required to think clearly.”

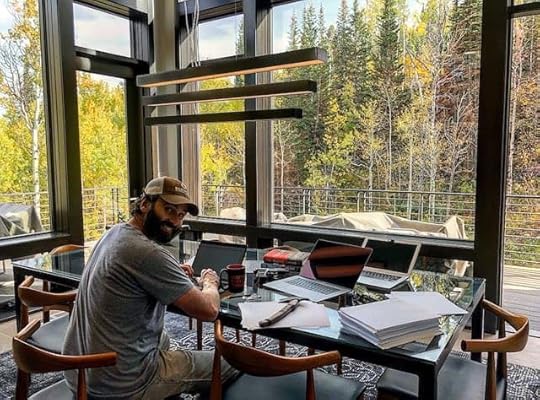

Anyway, this is all just preface to me reporting that I recently stumbled across another nice example of this work from near home phenomenon. It came in an episode of Ryan Holiday’s Daily Stoic podcast featuring the bestselling novelist Jack Carr talking about his latest James Reece thriller, In the Blood. For our purposes, it’s important to know that Carr has a beautiful home in Park City, Utah, which, based on photos he’s shared on social media, includes idyllic spaces to write; e.g.:

And yet, at roughly the 16:30 mark of the podcast interview, Carr reveals that in order to help focus while working on In the Blood, he ended up renting a rustic cabin across town, where he would chop wood to feed the stove, and write at a simple table.

Home is where the heart is, but it’s not necessarily where the mind reaches its full potential.

The post Jack Carr’s Writing Cabin first appeared on Cal Newport.May 25, 2022

Inbox Pause? How About an Inbox Reset?

Several readers have recently pointed me toward a productivity tool called Inbox Pause, which allows you to prevent messages from arriving in your email inbox for a set amount of time. You could, of course, simply decide not to check your inbox for this period, but as every knowledge worker who has ever used email has learned, it can be very, very difficult to resist a quick check when you know there are messages piling up, desperate for your response.

I like this tool. Among other benefits, it can provide a nice support system for time block planning. When you start a block that doesn’t require email, you can setup a pause to make sure you’re not tempted to abandon whatever demanding activity you’ve planned to instead fall back into the comfort of stupefying inbox sifting.

Pausing on its own, however, cannot fully solve the problem of communication overload. As I argue in my book, A World Without Email, the foundation of our overload is a widely-adopted collaboration style that I call the hyperactive hive mind. This is an approach in which work is coordinated with a series of ad hoc, on demand, unscheduled, back-and-forth messages — be them emails, instant messages, or texts (the actual technology doesn’t really matter).

Each ongoing back-and-forth conversation of this type can generate dozens of messages in a short period of time. Given dozens of these conversations unfolding concurrently, you can easily confront a hundred or more messages a day, many of which require a relatively quick response, as they’re part of an extended back-and-forth that presumably cannot be dragged out too long.

In this context, there is only so many pauses you can take, as every time you step away, you’re potentially delaying many different back-and-forth discussions, perhaps critically, and ensuring an even more intimidating, tottering pile of urgency awaiting you when the pause completes.

What’s the ultimate solution? An inbox reset. As I detail in my book, you need to start enumerating every type of conversation that’s unfolding over email (or IM, or text), and ask for each, is there a process, or tool, or set of new rules, that would allow us to get this work done in the future without trading multiple unscheduled messages?

To be clear: these resets are a pain. They require you to work with others to come up with more structured ways of collaborating. It would be easier if we could instead deploy hacks or tips all on our own. But in the context of knowledge work, despite what we’ve been told, productivity isn’t personal, it’s instead systematic, and must be addressed collectively.

In the meantime, however, we must do what we can to survive the onslaught of the hyperactive hive mind. Taking a pause on a regular basis is a good start.

The post Inbox Pause? How About an Inbox Reset? first appeared on Cal Newport.May 16, 2022

Taking a Break from Social Media Makes you Happier and Less Anxious

In my writing on technology and culture I try to be judicious about citing scientific studies. The issues involved in our ongoing wrangling with digital innovations are subtle and often deeply human. Attempts to exactly quantify what we’re gaining and losing through our screens can at times feel disconcertedly sterile.

All that being said, however, when I come across a particularly well-executed study that presents clear and convincing results, I do like to pass it along, as every extra substantial girder helps in our current scramble to build a structure of understanding.

Which brings me to a smart new paper, written by a team of researchers from the University of Bath, and published last week in the journal of Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. It’s titled “Taking a One-Week Break from Social Media Improves Well-Being, Depression, and Anxiety,” and it caught my attention, in part, because of its parsimonious design.

As I reported last fall in The New Yorker, a problem with existing research on social media and mental health is that it often depends on analyzing large existing data sets. Finding strong social psychological signals in these vast collections of measurements is tricky, as outcomes can be quite sensitive to exactly what questions are asked.

This new paper avoids these issues by deploying a gold-standard for studying human impacts: the randomized control trial. The researchers gathered 154 volunteers with a mean age of 29.6 years old. They randomly divided them into an intervention group, which was asked to stop using social media for one week (with a focus, in particular, on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok), and a control group which was given no instructions.

At the end of this week, the researchers found “significant between-group differences” in well-being, depression, and anxiety, with the intervention group faring much better on all three metrics. These results held even after control for baseline scores, as well as age and gender.

The researchers further found that they could obtain smaller, but still significant improvements in depression and anxiety by having users simply reduce the time they spend on Twitter and TikTok. The biggest effects, however, came from full abstention.

Caveat emptor, I don’t know these researchers, nor have I run this work by the experts I trust in the field, so I can’t vouch without equivocation for the strength of its findings. But given the simple study design and the clear effects it revealed, the message here seems to be clear: social media hurts mental health. Which motivates an obvious follow-up question: Why do we insist on still shrugging our shoulders and continuing to treat the use of these tools like some sort of unavoidable civic and professional necessity?

The post Taking a Break from Social Media Makes you Happier and Less Anxious first appeared on Cal Newport.May 12, 2022

My “Oldest” Productivity Strategy

I recently posted a video about one of my oldest and most successful work strategies: fixed-schedule productivity. The idea is simple to describe:

Choose a schedule of work hours that you think provides the ideal balance of effort and relaxation.Do whatever it takes to avoid violating this schedule.These simple limits, however, can lead to complex productivity innovations. In my own life, the demands of fixed-schedule productivity helped me develop what became my time blocking and shutdown ritual strategies.

In my video, which is actually a clip taken from episode 193 of my podcast, I call this my “oldest” productivity strategy. I don’t think that’s literally true, but it is old. I went back and did some digging and discovered that I first wrote about this idea here on my blog back in 2008, meaning I had probably been deploying it for at least a couple years before then. In 2009, I wrote a more epic post on the topic for my friend Ramit Sethi’s blog which was subsequently featured on Boing Boing. Which is all to say, fixed-schedule productivity has been bouncing around for a while.

Anyway, watch the video if you want a more detailed discussion of the strategy, why it works, and how I’ve used it in my own life.

The post My “Oldest” Productivity Strategy first appeared on Cal Newport.May 9, 2022

Aziz Ansari’s Digital Minimalism

Not long ago, I watched Aziz Ansari’s new Netflix special, Nightclub Comedian. I was pleasantly surprised when, early in the show, Ansari demonstrates his commitment to escaping tech-driven distraction by showing off his Nokia 2720 flip phone (see above). Soon after the special was released, Ansari elaborated on his personal brand of digital minimalism in a radio interview:

“Many years ago, I kind of started turning off the internet, and I deleted all social media and all this stuff, and I’ve slowly just kept going further and further. I stopped using email, maybe, four years ago. I know all this stuff is like, oh yeah, I’m in a position where I can do that and have certain privileges to be able to pull it off, an assistant or whatever, but all that stuff I do helps me get more done.”

This commitment to craft over servicing digital communities is not uncommon among top comedians. Dave Attell, who is widely considered by his peers to be one of the best living joke writers, has a lifeless Twitter account dedicated primarily to announcing show dates. Dave Chappelle doesn’t even bother using Twitter at all. “Why would I write all my thoughts on a bathroom wall,” he quipped last year when asked about his lack of presence on the popular platform.

Professional comedy provides a useful test case for the importance of digital engagement. It’s a field in which both name recognition and craftsmanship matter: you need an audience, but you also need to consistently deliver. Many top practitioners, such as Ansari, Attell, and Chappelle, experimented with this trade-off and ultimately decided that focusing on being so good you can’t be ignored, not the frenetic managing of digital legions, was the surest route to sustainable success.

I recently had to spend a fair amount of time on Twitter to research my latest New Yorker essay. Encountering that onslaught of manic dispatches, tinged with equal parts desperation and pyrrhic triumph, I could only hope that these insights forged in the world of high-level entertainment will soon spread.

The post Aziz Ansari’s Digital Minimalism first appeared on Cal Newport.May 3, 2022

The Real Problem with Twitter

Last week, Twitter accepted Elon Musk’s acquisition bid. The media response was intense. For a few days, it was seemingly the biggest story in the world: every news outlet rushed out multiple takes; commentators fretted and gloated; CNN, for a while, even posted live updates on the deal on their homepage.

As I argue in my latest essay for The New Yorker, titled “Our Misguided Obsession with Twitter,” these varied responses were unified by a shared belief that this platform serves as a “digital town square,” and therefore we should really care about who controls it and the nuances of the rules they set.

But is this view correct?

Drawing on Jon Haidt’s epic Atlantic article on the devolution of social media (which I recently discussed in more detail on my podcast), I note that Twitter is far from a gathering place for representative democratic debate. Its most active users are much more likely to be on the political extremes. They’re also whiter and richer than the average American, not to mention that they have the time to spend all day tweeting, which is quite a rarified luxury.

Here’s Ethan Porter, a media studies professor at George Washington University, elaborating this latter point in a recent Washington Post article:

“The thing about Twitter is, it’s actually quite a demanding platform. In other words, to really participate on Twitter, you need to be a really active Twitter user, and the number of people who have jobs that allow them to be active Twitter users is pretty small.”

The real outrage, I conclude, is not the details of how Elon Musk might change Twitter, but the fact that so many people in positions of power — politicians, business leaders, journalists — still pay so much attention to these 240-character missives.

“Twitter’s increasingly heated wrangling is not just far from a considered democratic debate,” I write, “but has truly become a spectacle driven by a narrow and unrepresentative group of elites.”

This may be optimistic thinking, but I’m hoping that the average person’s response to the media frenzy that surrounded Musk’s acquisition will spark pushback — not against the service’s new owner, but instead against all the people in positions to affect out daily lives who keep giving it such rapt attention.

Anyway, for more detail on my take, see the full article…

The post The Real Problem with Twitter first appeared on Cal Newport.Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers