Cal Newport's Blog, page 11

December 20, 2021

Analog January: The No Twitter Challenge

Back in December of 2019, inspired by the recent release of my book, Digital Minimalism, I announced what I called the Analog January Challenge. The goal of the challenge was to complete a series of five commitments designed to help you develop quality, non-digital alternatives to screen-based distractions.

Two years later, I’m bringing back the Analog January Challenge. In response to the urgent anxieties of our current moment, however, I’m simplifying its demands to the following:

Do not access Twitter for the month of January. In its place, learn a new non-professional skill or pursue a hobby project for no other reason than inherent enjoyment. When you feel the need to check Twitter, work on this initiative instead.

And that’s it.

I’m motivated in designing this new challenge by the reality that Twitter has had an unusually toxic run in recent years. It’s become difficult to make it through more than a handful of tweets before you encounter something that either makes you angry, or depressed, or, more often than not, incredibly anxious.

In fairness, this service wasn’t intentionally designed to grasp our brain stem and squeeze it into an inflamed pulp of enraged emotions, but it turned out to be exceptionally good at accomplishing exactly this insidious goal. You might log onto Twitter for an important and noble reason, like checking Washington Nationals baseball trade rumors, but then, out of the corner of your eye, you see a trending tweet about white supremacists using Omicron to accelerate climate change, and boom: your innocent contentment is shattered.

So why not take a break? For thirty-one blissfully peaceful days. A period to re-learn that there are other, more meaningful, more analog ways to quiet our chattering brain. We can learn how to knit, or buy a lathe, or 3D print mini spaceships for a strategy game we’re inventing with our kids. For just one month, why not take a breather from the panic and outrage?

In comparison to other digital tools, Twitter offers little that you can’t either replicate or easily live without for a month. When it comes to distraction, you can find much more engaging fare on streaming video services or podcasts. When it comes to news, unless you’re a TV producer or newspaper editor, you don’t need to be nearly that up to date. When it comes to connection, send text messages, FaceTime, and, to the extent possible, do things with real people in real places. When it comes to building an audience, they’ll still be there in February, so in the meantime, why not create something special they’ll really appreciate when you return?

This 2022 version of the Analog January Challenge is, for sure, more stripped-down than its antecedent from two years earlier. But this is, if anything, a moment for simplicity. So I hope you’ll join me. And if you don’t, keep an eye on Washington Nationals tweets and send me a note if there’s anything I should know.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.December 16, 2021

Why I Changed My Email Setup

Last week, for the first time in a long time, I made a substantial change to the configuration of my email inboxes.

This might seem somewhat out of character. As readers of A World Without Email know, I’m largely indifferent about using hacks and technical fixes to improve your email experience. The real problem, I argue in that book, is the implicit decision to coordinate so much of your collaborative efforts with unscheduled back-and-forth messaging. This hyperactive hive mind workflow doesn’t scale: once you have dozens of these conversations unfolding concurrently, you have no choice but to check your inbox constantly, as otherwise you might slow down the ongoing collaboration.

According to this analysis, the solution to email overload is not handling messages more efficiently, but instead preventing them from arriving in your inbox in the first place. You must, in other words, replace the hyperactive hive mind workflow with alternatives that do not generate so much unscheduled communication.

Motivated by these ideas, most of my efforts in recent years to tame my email have focused on implementing better processes — methods for collaboration that don’t just depend on dashing off quick messages. And yet, I still found myself recently needing to make a change to the technical details of my communication setup.

The instigating factor was cognitive exhaustion. On a typical workday, I might put aside a single 30 – 60 minute block in my time-block plan to process my inbox. I use the term “inbox” loosely here, because over the years I’ve built up many different email addresses: my original Gmail address, which I setup back when the service was in beta testing and you needed an invitation to join, a couple academic addresses, and three writing-related addresses connected to my calnewport.com domain. I was forwarding all of these messages to my original Gmail inbox and using filters to move them into dedicated labels, creating mini-inboxes I could quickly cycle through.

The total number of relevant messages arriving through these six addresses on a typical day is not excessive. (Remember, I spend a lot of time combatting the hyperactive hive mind approach to collaboration). But I was still finding the process of responding to them to be oddly draining; a time block I dreaded.

In the end, it was research I had conducted for A World Without Email that helped reveal the issue. In that book, I give a thorough survey of the research literature on cognitive context switching. It turns out that it’s expensive and relatively time-consuming to switch your attention from one target to another, as the process requires a complicated dance of neural network activation and inhibition. In the book, I used this research to underscore the costs of returning to your inbox every few minutes: each such check instigates another expensive switch. It also explains, however, why I was feeling such fatigue during the singular task of responding to messages.

The problem was not the number of emails I encountered, but the fact that were coming from multiple distinct contexts: my personal life, my academic life, and my writing life. Faced with twenty messages to answer, no single missive in the pile would require more than a few minutes of thinking to dispatch. The issue is the context switching between messages: a question from a family member, then a meeting request from a student, then a note about an issue with a podcast advertiser — switch, switch, switch. The first reply is easy, by the tenth I’m blocked.

So I decided to separate these contexts. I now have three distinct Google Workspaces, each with their own username and password: one for my personal address, one for my Georgetown addresses, and one for my calnewport.com addresses. (Technically, I also have a fourth Google Workspace, for my New Yorker address, but I don’t use it much.)

I no longer schedule “checking my inbox” as a general activity. I instead check these individual inboxes at times when it seems appropriate. I can already notice the difference. When every note in a given inbox falls within the same cognitive context, much less friction aggregates as I move from message to message. Furthermore, I can now schedule inbox checks adjacent to appropriate work blocks: checking my writing inbox, for example, at the end of a podcast recording session, when my mind is already thinking about relevant issues.

If we believe our minds to be black box computational devices, none of this makes sense. Why waste time maintaining three different inboxes if you end up processing the exact same number of messages each day as before? Once we realize, however, that our brain is not a computer, and that it functions in an idiosyncratic, messy manner, these types of humanistic productivity contrivances sometimes turn out to be exactly what we need.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

December 3, 2021

The Books I Read in November 2021

Since last spring, I’ve been pursuing the goal of reading five books a month. To meet this mark, I start with a foundation of daily reading, but then, when I get momentum going on a given book, I schedule extra reading sessions in my time block schedule, allowing me to accelerate toward completion. I also include at least one audio title each month, and try to mix together a diversity of genres to keep things interesting.

Recently, on my podcast, I adopted the habit of of briefly reviewing the books I read each month. I thought it might be fun to replicate these reviews here in written form (an homage, I suppose, to my friend Ryan Holiday’s epic and longstanding Reading List newsletter).

Without additional preamble, here are the five books I completed* in November 2021:

Relic

Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child

One of the best thrillers of the 1990s. I re-read this book in honor of Halloween this year (but didn’t finish until November) and was pleased to find that it held up. The basic plot is straightforward: an apparent monster is loose in the American Museum of Natural History. The execution, however, is superb. The book mixes multiple genres, including techno-thriller, mystery, and horror, and leans into the fact that Preston spent eight years working at the Museum before hatching the scheme to write this thriller with Child.

Steven Spielberg: A Biography

Joseph McBride

After reading a film studies textbook in October (long story), I’ve been on a bit of a popular cinema kick. It was this interest that led me to Joseph McBridge’s exhaustively researched 1997 biography of the wunderkind director. McBride deploys a loosely Freudian approach to his subject, meaning that you should prepare for a long analytical treatment of Spielberg’s childhood. The narrative picks up steam, however, when a family friend at Universal, impressed by Firelight, an amateur 8mm feature Spielberg filmed using his friends and neighbors as cast, wrangles up an internship for the teenager on the studio lot. Spielberg haunts sets and the commissary, obsessively soaking in the trade. He then puts everything he learned into a feature short called Amblin, which is so polished that Universal pulls the trigger to hire the precocious 21-year-old to a television directing contract. Spoiler alert: things subsequently go quite well. My key takeaway from the book: Spielberg, for reasons that McBride can never quite nail down, was capital-D driven. His story provides a master class in the potential of mixing relentless ambition, talent, and perfect timing.

K: A History of Baseball in Ten Pitches

Tyler Kepner

I actually bought this book back in July from one of my favorite booksellers, Labyrinth Books, on Nassau Street, in Princeton, New Jersey. I didn’t get around to really reading it, however, until this fall. The book provides a brief oral history of ten important baseball pitches. Kepner, a baseball columnist for the Times, mixes a lot of original interviews with aging baseball greats with archival research. As you might expect from a Times reporter, the writing craft is superb. As someone who came to baseball relatively late (my twenties), however, I occasionally found myself drowning in repeated references to players I didn’t recognize. The book leans more towards nostalgia than a Moneyball-style contrarian sharpness.

Future Ethics

Cennydd Bowles

For obvious reason, I’ve recently taken up a professional interest in digital ethics. Bowles’ 2018 book provides a useful survey of the various problems tackled by this nascent field, and the frameworks that have emerged to tackle them. I particularly enjoyed Bowles sharp summary of Peter-Paul Verbeek’s Mediation Theory, which I first came across in Verbeek’s classic, Moralizing Technology, and which I think provides arguably the best take we currently have on our complicated relationship with modern tools. (Indeed, I would argue that Digital Minimalism is itself a practical instantiation of this theory’s main proposals.)

Numbers: The Language of Science

Tobias Dantzig

Original written in the 1930s, and boasting a book jacket blurb from Albert Einstein (“Beyond doubt the most interesting book on the evolution of mathematics which has ever fallen into my hands”), Number provides a cultural history of our increasingly complicated understanding of what we mean by the notion of a number. Dantzig starts with the emergence of a “counting sense” in humans that goes beyond what other animals can manage, and ends with Cantor’s uncountable infinities. Though the book perhaps gets a little too math-ey by the end (and this is coming from someone who is literally teaching discrete mathematics to university students at the moment), Dantzig provides a compelling overview of what we mean when we talk about “numbers,” and why this is a question that we must repeatedly keep re-visiting.

* Not every book is read within the exact days of a given month, so my rule is to count each book in the month in which I complete it.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.November 22, 2021

The Forgotten Tale of George Lucas’s Writing Tower

In early 1973, George Lucas was living modestly with his wife, the film editor Marcia Lou Griffin, in a one-bedroom apartment in Mill Valley, a small town in Marin County, just north of San Francisco over the Golden Gate Bridge. Lucas’s situation drastically changed that summer when Universal released his second feature film, American Graffiti.

The movie was a major hit, earning over $60 million in its first year alone, before eventually going on to rake in $250 million in the decades that followed. Given that Graffiti was made on a shoestring budget of only $775,000, it still ranks as one of the most profitable movies of all time. Lucas, of course, enjoyed immense personal benefit from this success. His fledgling production company, LucasFilm, received $4 million from the movie in 1973, an amount worth over $16 million in today’s dollars.

I recently read about this particular beat in Lucas’s long narrative in Chris Taylor’s exhaustively-researched 2014 book, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe. As Taylor details, Lucas resisted the urge to follow the path of his friend Francis Ford Coppola, who had made a fortune the previous year with the runaway success of The Godfather, and then promptly spent the money on a “massive” Pacific Heights mansion and a private jet lease. He and Griffin instead bought a rambling Victorian house on Medway road in the Marin County village of San Anselmo.

What caught my attention most, however, is what Lucas did next.

According to Taylor, Lucas worked from old photographs of the house to reconstruct a two-story tower, including a fireplace and wrap-around windows offering a scenic view of nearby Mount Tam. It was in this tower, in the two years that followed, that Lucas sequestered himself most afternoons to sit at a three-sided desk he built out of old doors and grind out a new script for a movie concept that had long fascinated him, but was proving immensely difficult to reduce into a digestible story. His working title for the project: “The Star Wars.”

To my dismay, I couldn’t locate any extant images of Lucas’s writing tower. (The best I could find was the photo reproduced above, which shows Lucas in the house at Thanksgiving in 1977.) But as with last week’s essay about Eoin Colfer devising the mega-bestselling Artemis Fowl series in a well-constructed backyard shed, I think this case study underscores the more general point that, for professional creatives, spending money to upgrade the aesthetics of your workspace is not just an exercise in expression, but is perhaps instead one of the best business investments you’ll ever make.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.November 13, 2021

The Bestselling Magic of the Writing Shed

A few years ago, my family faced a housing dilemma. We lived at the time in our first house, a small cape cod near the top of an elongated cul-de-sac, situated on a bluff above Sligo Creek, a half mile outside downtown Silver Spring. We had two kids who comfortably shared an upstairs bedroom. But then my wife and I decided they needed a new brother, and we soon realized that we might not actually have anywhere to put him.

So we started thinking through options to gain more space. At one point, I landed on what I deemed to be an ingenious plan. We would give up my home office and instead build, in the corner of our small backyard, a custom writing shed. Inspired by the cabin Michael Pollan built in the woods outside his home in Kent, Connecticut, I began to daydream about making that short walk from our back door to a wood-paneled oasis; heated in the winter by a marine pellet stove, and cooled by tilt-open windows in the pleasant DC spring.

For various reasons, including the potential illegality of cramming an outbuilding of this size into our cramped yard, we ended up instead buying a new house ten minutes down the road. But the daydream of my impractical writing shed lingered.

Which is all a long way of establishing the importance of what happened earlier today. I was watching an old episode of a promotional show called Disney Insider with our youngest son (now three), when we were suddenly confronted with a great example of a writer who actually acted on my impulse. The segment in question focused on Eoin Colfer, the Irish author of the massively successful Artemis Fowl book series.

At the time of the segment’s filming, Colfer lived in a modest row house near the town center of Wexford, Ireland. After the birth of their first child, he converted a shed in the back of their narrow garden into an office, and, by the looks of it, he did it right. The building is clad in red stained wood, with visible slatting and a modern slanted roof. Inside there’s room only for a desk that faces wall-to-wall windows looking back at the house. Behind him is a simple shelf holding the books crafted in the space.

It’s actually hard to find images of the shed online. The picture at the top of the post, extracted from Colfer’s Twitter account, is one of the better examples I could find,

Here’s another incomplete image that showcases the shelf behind the desk:

And one that reveals some of the front windows:

The television segment we watched did a much better job of showcasing the shed’s pleasing, depth-supporting aesthetics, both inside and outside. But the above images provide a good general sense of the space.

Perhaps non-surprisingly, Colfer no longer writes in this modest shed. A little internet sleuthing reveals that he eventually moved to a stately manner house, situated on 14 acres in the countryside outside Wexford proper. The property included a collection of free-standing stables and garages, one of which was converted into an elegant new office clad in light American oak. Even more recently, Colfer sold this property to move to Dublin.

When you sell 25 million books, you have options.

It was nice to see, however, that the spark that initiated this wildly lucrative and impactful writing career was a small but intentional shed built at the back of a narrow garden. Perhaps my daydream wasn’t so far-fetched after all.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.November 4, 2021

When Facebook Came Calling…

When I give interviews about the potential harms of social media, I often tell a story from early in my career as a professor. In this tale, I was walking across the campus of a well-known university, on my way to give a talk to a student group about stress and academic success. I was escorted by a professor involved with the school’s student mental health clinic.

As we chatted, she casually mentioned an interesting development they’d noticed at the clinic. A few years earlier, seemingly all at once, the number of students they served significantly increased. Even more curious, the students all seemed to be suffering from the same cluster of previously-rare anxiety-related issues.

I asked her what she thought explained this change.

She responded without hesitation: “smartphones.”

As she then elaborated, the first classes to arrive on campus already immersed in the phone-enabled world of social media and ubiquitous connectivity were suddenly and more notably anxious than those who had come before.

I’ve been involved in many public discussions and debates on the promises and perils of network technologies in the years that have elapsed since that fateful conversation. I even ended up writing a bestselling book on the topic. Throughout this whole period, however, that story I first heard as a young professor stuck with me.

Which is why I was fascinated when, earlier today, a colleague of mine at Georgetown pointed me toward a new paper, co-authored by a trio of researchers from Stanford, MIT, and the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance, that argues that the experience described to me so many years earlier might have actually been quite common.

This paper, titled “Social Media and Mental Health,” leverages an ingenious natural experiment. When Facebook first began to spread among college campuses in the first decade of the 2000s, its introduction was staggered, often moving to only a few new schools at a time. (I still remember when Facebook arrived at Dartmouth during my senior year in 2004. It was a big event.)

The authors of this paper connect a dataset containing the dates when Facebook was introduced to 775 different colleges with answers from seventeen consecutive waves of the National College Health Assessment (NCHA), a comprehensive and longstanding survey of student mental health.

Using a statistical technique called difference in differences, the researchers quantified changes in the mental health status of students right before and right after they were given access to Facebook. Putting aside for now some technical discussion about how to properly obtain robustness from such analyses, the authors summarize their results as follows:

“Our main finding is that the introduction of Facebook at a college had a negative effect on student mental health. Our index of poor mental health, which aggregates all the relevant mental health variables in the NCHA survey, increased by 0.085 standard deviation units as a result of the Facebook roll-out. As a point of comparison, this magnitude is around 22% of the effect of losing one’s job on mental health.”

They go on to elaborate that the condition driving the results are “primarily depression and anxiety-related disorders.”

There are many other interesting findings described in this paper. The authors note, for example, that academic performance also suffered after the introduction of Facebook. As a placebo check, they then looked at physical health, which shouldn’t be impacted by the arrival of social media, and found, as expected, that Facebook’s arrival didn’t impact this variable.

I recommend that you read the full paper for more details. But for now, I’m both pleased and dismayed to learn that the story that originally helped pique my interest in the topic of social media and mental health so many years earlier was indeed a warning sign for what was to come.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

October 11, 2021

A Pastor Embraces Slowness

I recently received an interesting email from a Lutheran pastor named Amy. She had read some of my recent essays on slow productivity (e.g., 1 2 3), and heard me talk about this embryonic concept on my podcast, so she decided to send me her own story about slowing down.

“A few years ago, I realized I was on the verge of burnout with my job,” she began. To compensate for this alarming state of affairs, Amy took the following steps…

She quit social media.

She took off her phone any site or app that was “refreshable by design.”

She implemented my fixed-schedule productivity strategy by setting her work hours in advance, then later figuring out how to make her efforts fit within these constraints.

She began to take an actual Sabbath, inspired, in part, by Tiffany Shlain’s book, 24/6: The Power of Unplugging One Day a Week.

She forwarded all work calls to voicemail and put in place a rule saying she must wait 24 hours before replying to any message that either made her upset or elated.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, she began scheduling less work for herself. Following an adage she first heard in seminary, she scheduled only two-thirds of her available work hours, leaving time free to handle pastoral emergencies, and enabling, more generally, margin surrounding her daily activities.

Amy feared this embrace of slow productivity would generate uproar from her parishioners and spawn relentless crises and problems. The reality turned out to be less dramatic:

“When I experimented by ceasing to do some things, and doing other things by putting in less effort, I heard nothing back. Nobody got really upset (at least not to my face). And when people have gotten upset about things, I’m better able to deal with it because I’m more rested, I have a life, it’s not as stressful as it used to be for me when my work mode was more reactive.”

Reflecting on her experiments with doing less, but doing what remains better, Amy reached a telling conclusion: “Time management is a core spiritual practice.”

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.September 25, 2021

On the Source of Our Drive to Get Things Done

In a recent essay for the New Yorker, I take a closer look at the growing popular dissatisfaction with the concept of “productivity,” a trend I underscore, in part, by citing some of the comments from readers of this newsletter.

In my piece, I focus on the precise economic definition of this term, which measures the output produced from a fixed amount of input. I argue that many knowledge workers resent the fact that the responsibility for maximizing this notion of productivity has been put solely on their shoulders. In the context of office work, I claim, the decision to make productivity personal has been largely negative.

There is, however, another definition of this term that I didn’t discuss in my New Yorker piece, but which is also worth investigating: its colloquial interpretation as a tendency toward activity and measurable accomplishment.

I increasingly encounter a strain of critique that dismisses this interpretation as an example of false class consciousness, arguing that we strive toward arbitrary fitness goals, or feel compelled to carefully document a dinner on Instagram, or race to finish reading the latest hot novel, because we’ve internalized a culture of production designed to ultimately help the capitalists exploit our labor. Or something like that.

Here I think reality is way more interesting and complex. Consider, for example, a paper published earlier this month in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, written by Marissa Sharif, Cassie Mogliner and Hal Hershfiled, and titled: “Having Too Little or Too Much Time is Linked to Lower Subjective Well-Being.”

This paper reports on the analysis of two large-scale time use data sets spanning over 35,000 Americans, and find that while it’s true, as expected, that having too little discretionary time lowers subjective well-being, the same unhappiness is also shown for having too much.

As the authors write:

“Having an abundance of discretionary time is sometimes even linked to lower subjective well-being because of a lacking sense of productivity. In such cases, the negative effect of having too much discretionary time can be attenuated when people spend this time on productive activities.”

Contrary to the critical assumption that the drive to produce is primarily culturally mediated, these results hint at something that many feel intuitively: there’s something deeply human, and therefore deeply satisfying, about succeeding in making one’s intentions manifest concretely in the world.

At the same time, of course, we also feel intuitively that when we subvert this drive by putting onto our proverbial plates more than we can possibly conceive of accomplishing, the resulting sense of overload leaves us deeply unhappy.

The allure of productivity is therefore a complex one. We cannot dismiss it as the result of the evil master plan of mustache twirling capitalists. We also cannot embrace it as an unalloyed good. It’s a human drive tangled with the contradictory imperatives of culture.

Which is all to say, our relationship to productivity is a topic that certainly requires some more careful examination.

#####

(It’s here that I should probably mention that we’ve been attempting some form of this examination in recent episodes of my podcast, Deep Questions. If you don’t already subscribe to this show, you should!)

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.September 7, 2021

What Would Happen If We Slowed Down?

In my recent New Yorker essay on overload, I noted that many knowledge workers end up toiling roughly 20% more than they have time to comfortably handle. This is, in some sense, the worst possible configuration, as it creates a background hum of stress, but is just sustainable enough that you can keep it up for years.

My explanation for the universality of this 20% rule is that it arises as a natural result of leaving knowledge workers to self-regulate their workload. It’s difficult for even the most organized and intentional among us to manage a constant influx of requests, and messages, and project proposals, and, God help us, Zoom meeting invites — so we default to a simple heuristic: start saying “no” when we feel stressed, as this provides psychological cover to retreat in an otherwise ambiguous terrain of never-ending potential labor.

The problem with this strategy, of course, is that we don’t start pulling back until after we have too much going on: leading to the 20% overload that’s so consistently observed.

The question left unexamined in my essay is what it would look like if you rejected this rule. What if, for example, you aimed to work 20% less than you had time to reasonably handle? If you have a relatively autonomous, entrepreneurial type job, this would mean saying “no” to more things. It would also mean, on the daily scale, being more willing to end early, or take an afternoon off to go do something unrelated, or extend lunch to read a frivolous book.

Here’s what I want to know: how much would this hurt you professionally? As I move deeper into my exploration of slow productivity, I’m starting to develop a sinking suspicion that the answer might be “not that much.”

If you worked deeply and regularly on a reasonable portfolio of initiatives that move the needle, and were sufficiently organized to keep administrative necessities from dropping through the cracks, your business probably wouldn’t implode, and your job roles would likely still be fulfilled. This shift from a state of slightly too much work to not quite enough, in other words, might be less consequential than we fear.

Or maybe not.

The issue is that not enough people are asking these questions. We know the costs of consistently squeezing in those extra evening email replies, or pushing through that one last extra block on our time block schedule, but few have yet taken the time to really confront the supposed benefits. We care a lot about doing well with the work on our plate (as we should), but not nearly enough about asking how big that plate should be in the first place.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.September 1, 2021

Revisiting Parkinson’s Law

I first came across Parkinson’s Law in Tim Ferriss’s 2007 book, The 4 Hour Workweek. Ferriss summarized it as follows:

“Parkinson’s Law dictates that a task will swell in (perceived) importance and complexity in relation to the time allotted for its completion. It is the magic of the imminent deadline. If I give you 24 hours to complete a project, the time pressure forces you to focus on execution, and you have no choice but to do only the bare essentials.”

Ferriss suggests that you should therefore schedule work with “very short and clear deadlines,” arguing that this will greatly reduce the time required to make progress on important tasks.

This advice is sound. After reading Ferriss’s book, I began to work backwards from a constrained schedule — forcing my professional efforts to fit within these tight confines. As predicted by Parkinson’s Law, these restrictions don’t seem to decrease the quantity of projects on which I make progress. If anything, I seem to get more done than many who work more hours.

This is all prelude to me noting that I have fond feelings for Parkinson’s Law. Which is why I was so surprised when recently, as part of the research for my latest New Yorker essay, I revisited the original 1955 Economist article that introduced the concept and found a whole other layer of meaning that I had previously missed.

Parkinson opens his essay with the pronouncement highlighted by Ferriss: “It is a commonplace observation that work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.”

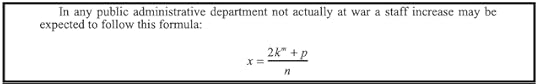

Parkinson then provides statistical evidence for this phenomenon, showing that the British naval bureaucracy grew even as the navy it served shrunk after WWI. He details an explanation for this counterproductive behavior that culminates in (satirically) precise mathematical formulas, e.g.,:

The details of his explanation are less important than its general implication: in the absence of strict direction, work systems can self-regulate in unusual ways. The British bureaucracies Parkinson studied grew according to internal dynamics that had little to do with the work they were meant to execute. They became their own beings with their own objectives.

Ferriss popularized the personal version of Parkinson’s Law, which correctly notes that our work expands to fill the time we give it. The original Economist essay on the topic also embeds an organizational version of the law, which I read to say that if you leave a group, or a team, or a company to operate without sufficient structure, they may converge toward unexpected and unproductive behaviors. Indeed, the hyperactive hive mind I popularized in A World Without Email can be seen as a 21st century instantiation of the organizational variant of Parkinson’s Law.

The mark of a good polemic is the ability for its readers to extract multiple layers of productive meaning. By this measure, we must admit, Parkinson wrote one hell of an essay.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers