Cal Newport's Blog, page 13

May 17, 2021

Luke Skywalker: Digital Minimalist

[image error]

I recently returned to a book I first discovered earlier in the pandemic: The Power of Myth. It consists almost entirely of edited interview transcripts from a now classic, wide-ranging filmed conversation between Bill Moyers and Joseph Campbell, which originally spanned over twenty hours of footage, but was later narrowed down to a handful of 60-minute episodes that aired on PBS in 1988.

You’ve probably heard of this interview as it went on to become one of the most watched series in public television history. Though it covers a dizzyingly diverse set of topics — from dragons, to Gaia, to religious fundamentalism — it attracted attention at the time in large part because George Lucas had previously admitted to referencing Campbell’s 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, to help write the script for Star Wars.

Accordingly, the bulk of the interview is conducted at Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch, and Moyers and Campbell eventually come around to obligingly unpacking the role of the Hero’s Journey monomyth in explaining the resonance of Lucas’s 1977 blockbuster.

What caught my attention, however, was a brief aside about Star Wars that I don’t remember from the original PBS special. Near the end of interview, Moyers recalls:

“When I took our two sons to see Star Wars, they did the same thing the audience did at that moment when the voice of Ben Kenobi says to Skywalker in the climatic moment of the last fight, ‘Turn off your computer, turn off your machine and do it yourself, follow your feelings, trust your feelings.’ And when he did, he achieved success, and the audience broke out into applause.”

What interested me about this observation was not just that digital minimalists existed even in a galaxy far, far away, but that right here on our home planet, as earlier as the 1970s, we already sensed that there was something dehumanizing about the newly emerging industry of interactive digital technology.

We often need these tools, of course, to metaphorically blow up our Death Stars, but we applaud the loudest when it’s what makes us most human that triumphs in the end.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.May 13, 2021

On Productivity and Remote Work

[image error]

Early in the pandemic, I wrote a big piece for the New Yorker about the potential implications of our sudden shift to remote work. One of my predictions was that the shortcomings of the largely improvisational and informal methods by which we currently organize knowledge work — what I call “the hyperactive hive mind” — would be exaggerated by this shift, leading to even more overload:

“In such a chaotic work environment, there are profound advantages to gathering people together in one place. In person, for instance, the social cost of asking someone to take on a task is amplified; this friction gives colleagues reason to be thoughtful about the number of tasks they pass off to others…In other ways, meanwhile, offices can be helpfully frictionless. Drawn-out e-mail conversations can be cut short with just a few minutes of spontaneous hallway conversation. When we work remotely, this kind of ad-hoc coördination becomes harder to organize, and decisions start to drag.”

New research supports this prediction. A working paper recently published by a group of respected economists from the University of Chicago carefully studies a group of over 10,000 IT professionals to assess the impact of pandemic-induced remote work.

Here’s the key finding:

“Total hours worked increased by roughly 30%, including a rise of 18% in working after normal business hours. Average output did not significantly change. Therefore, productivity fell by about 20%.”

This result is important.

It’s become common to hear business leaders claim that the lesson of the pandemic is that telecommuting can be just as productive as working in an office. But we have to be careful about terminology. When they say “just as productive,” what they often really mean, as found in the Chicago study, is that the workers were still able get their work done when at home.

What this observation misses, as also found in the study, is that getting this same work done now requires more total hours. That’s a decrease in productivity. And because these efforts now necessitate more work in the morning or evenings, they’re likely creating more worker dissatisfaction and burnout.

Put bluntly, the hyperactive hive mind is not compatible with remote work. We managed to keep the proverbial ship afloat from our homes during the amplified disruption of the last year, but a 20% decrease in overall productivity is not a condition we can maintain in the long term.

This leaves us two options: either we bring everyone back to physical offices, or we finally get around to replacing the hive mind with more structured forms of collaboration. (As I point out in the New Yorker piece, software developers have an easier time moving their efforts remote because they long ago replaced the hive mind workflow — in which collaboration unfolds through frenetic, unscheduled messaging and meetings — with much more structured systems, like Scrum or Kan Ban).

I really hope we embrace the latter option, as not only will it make higher rates of remote work sustainable, it will make knowledge work better for everyone. But I fear the former option will end up seeming more attractive in the moment.

(Hat tip: Tyler Cowen)

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.May 6, 2021

The Neuroscience of Busyness

In a paper published last month in the journal Nature (summary), a group of scientists from the University of Virginia reported on a series of experiments designed to assess how we solve problems. When presented with a challenging scenario, humans cannot evaluate every possible solution, so we instead deploy heuristics to prune this search space down to a much smaller number of promising candidates. As this paper demonstrates, when engaged in this pruning, we’re biased toward solutions that add components instead of those that subtract them.

This quirk in our mental processing matters. Potentially a lot. As the authors of the paper conjecture:

“Defaulting to searches for additive changes may be one reason that people struggle to mitigate overburdened schedules, institutional red tape, and damaging effects on the planet.”

As I read about this finding, I couldn’t help but also think about the epidemic of chronic overload that currently afflicts so many knowledge workers. The volume of obligations on our proverbial plates — vague projects, off-hand promises, quick calls and small tasks — continues to increase at an alarming rate. There was a time, not that long ago, when the standard response to the query, “How are you?”, was an innocuous “fine”; today, it’s rare to encounter someone who doesn’t instead respond with a weary “busy.”

Does the wiring of our brains play a role in this reality?

I hadn’t thought about this possibility before, but this new paper raises some intriguing possibilities. The collision of knowledge work (a new thing) with the digital age (an even newer thing) disrupted the professional world, making many office jobs more haphazard and improvisational than ever before. Confronted with this novelty, perhaps our brains fell back to a default answer: do more!

Like the subjects in the experiments reported in this recent paper, however, the best solution to these problems might often instead be to do less. You want more out of your employees? Radically reduce their responsibilities, then leave them alone to execute. You want your small business to grow? Focus your attention on a single target, and give yourself the space to do it better.

Clearly brain biases are not the only factor involved in explaining the growth of busyness culture, but it’s a partial explanation that’s worth (if you’ll excuse the pun) keeping in mind.

(Hat tip: Jesse)

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

April 30, 2021

Favorable Conditions Never Come

In a sermon delivered at the height of World War Two, a period awash in distraction and despair, C.S. Lewis delivered a powerful claim about the cultivation of a deep life:

“We are always falling in love or quarreling, looking for jobs or fearing to lose them, getting ill and recovering, following public affairs. If we let ourselves, we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work. The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavorable. Favorable conditions never come.”

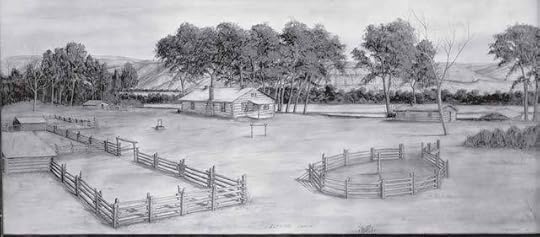

This quote reminds me of one my favorite Teddy Roosevelt stories, first recounted in his 1888 memoir, Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail. The tale begins in the spring, as the ice began to thaw on the Little Missouri River that passed through Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch. Under the cover of night, a band of infamous local horse thieves steal a boat from the Elkhorn.

Though the swollen river was treacherous, and the thieves dangerous, there was no doubt that Roosevelt had to pursue them. “In any wild country where the power of law is little felt or heeded, and where every one has to rely upon himself for protection,” he writes, “men soon get to feel that it is in the highest degree unwise to submit to any wrong.” With the help of his ranch hands, Bill Seward and Wilmot Dow, Roosevelt builds a new flat-bottomed scow, which the trio then pushes out into the ice-choked river to initiate a three-day journey to hunt down the fugitives.

What always caught my attention about this story was not the chase, but instead what Roosevelt brought with him for the adventure: a copy of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, which he would read in bursts, huddled under a blanket to keep rain off its pages.

We all face distractions from the deeper efforts we know are important: the confrontation of something not going right in our lives; an important idea that needs development; more time with those who matter most. But we delay and divert. It’s easier to yell at someone for doing something wrong than to yell in pride about something we did right. It’s easier to seek amusement than to pursue something moving.

At some point, however, there’s nothing left but to embrace Lewis’s call to “get down to our work,” even if the favorable conditions never come.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

April 20, 2021

The Productivity Funnel

In light of our recent discussions of “productivity,” both in this newsletter and on my podcast, I thought it might be useful to provide a more formal definition of what exactly I mean when I reference this concept.

In the most general sense, productivity is about navigating from a large constellation of possible things you could be doing to the actual execution of a much smaller number of things each day.

At one extreme, you could implement this navigation haphazardly: executing, in the moment, whatever grabs your attention as interesting or unavoidably urgent. At the other extreme, you might deploy a fully geeked out, productivity pr0n-style optimized collection of tools to precisely prioritize your obligations.

To make sense of these varied journeys from a broad array of potential activity to the narrowed scope of actual execution, I often imagine the three-level funnel diagramed above.

The funnel begins with the fundamental task of selection, where you determine which activities to commit to accomplish. Relevant ideas for this level can be found in books like First Things First, Essentialism, How to Do Nothing, One Thing, The Dip, and Year of Yes.

Once committed, these activities must then go through processing, organization, and storage. There are two goals for this funnel level: to avoid forgetting what you’re supposed to do, and to make smart decisions about what to work on next. Relevant ideas for this level can be found in books like Getting Things Done and The Bullet Journal Method. This is also where the Capture/Configure/Control philosophy I talk about on my podcast, or software like OmniFocus, Trello, Basecamp, and Asana, can help.

The final level focuses on the actual execution of whatever it is you’ve figure out you should be doing in the moment. This includes how you plan your day, the rituals you deploy to support your efforts, and the processes you’ve put in place to support more effective collaboration with others. Relevant ideas for this level can be found in books like Deep Work, A World Without Email, Daily Rituals, The War of Art, and Bird by Bird. Planning tools like my Time Block Planner are also useful here.

There are obvious benefits to defining the concept of productivity with this level of detail.

For one thing, it helps avoid the common mistake of focusing on one part of the funnel while avoiding others. There are many deep work aficionados, for example, who are obsessive about their depth rituals (execution), but are constantly forgetting or losing track of what’s on their plate (organization).

Similarly, it’s common to come across productivity geeks with complex organizational systems, who pay little attention to their overall workload (selection), and end up hopelessly overwhelmed, no matter how much they optimize their OmniFocus configuration.

By clearly delineating the three different levels of the productivity funnel, you can make sure each level gets at least some attention.

This detailed definition also adds nuance to anti-productivity criticism. A lot of this recent debate loosely associates the term “productivity” with an exploitative capitalist drive to maximize accomplishment. When viewed against the specificity of the productivity funnel, however, it becomes clear that this critique more accurately concerns only the activity selection level.

I agree that there’s an important debate to be had about how organizations and individuals implement activity selection (e.g., my recent post on slow productivity), but regardless of where this debate takes us, the other levels of the funnel remain important and largely orthogonal. In a post-capitalist collectivist utopia, where work is optional, and we’ve excised our souls of our past bourgeois internalization of the narratives of production, we’ll still have things we need to get done, and having an organizational system will still be better than haphazardly trying to keep track of these things in our minds (even Lenin had a task list).

Similarly, intentionality about execution can often enhance — not impede — slower lifestyles. If you don’t give serious thought to how you want to structure your days, it’s all too easy to fall back into distraction and shallow busyness.

I’m not sure if the funnel proposed above is complete. Indeed, I’m almost certainly missing aspects of productivity that are equally as important as the three levels I detail. But the more general movement here toward clarity in what we mean when we talk about productivity is worth encouraging.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

April 7, 2021

On Slow Productivity and the Anti-Busyness Revolution

Seven years ago, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang was a typical overworked, multitasking, slave to the hyperactive hive mind, Silicon Valley consultant. Feeling the symptoms of burnout intensify, he arranged a three-month sabbatical at Microsoft Research Cambridge. Here’s how he later described this period:

“I got an enormous amount of stuff done and did an awful lot of really serious thinking, which was a great luxury, but I also had what felt like an amazingly leisurely life. I didn’t feel the constant pressure to look busy or the stress that I had when I was consulting. And it made me think that maybe we had this idea about the relationship between working hours and productivity backward. And [we should] make more time in our lives for leisure in the classic Greek sense.”

The experience led him to ultimately publish a book titled, Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less. I remember this book because it came out the same year as Deep Work, and the two volumes were often paired as variations on a common emerging anti-busyness theme.

In the half-decade that has since transpired, an increasing number of new books have taken aim at our accelerating slide toward overload in both our work and our personal lives. Many of these new titles, somewhat in contrast to my writing, or that of Pang, have adopted a more strident and polemical tone — not only underscoring the issues, but also pointing a defiant finger at the forces which are supposedly to blame. Clearly the overwhelmed and overscheduled manner in which we currently operate isn’t working.

Which brings me to a question that more and more has been capturing my attention: What can we do about this unfortunate state of affairs?

It’s here that the insightful work that has probed this question in recent years falls somewhat short of sparking major change. The genre is currently dominated by economic materialist arguments: We work too much because of exploitive capitalist imperatives, and then overload our personal lives because we’ve internalized these narratives.

There is, of course, a crackling, subversive energy in this materialism — every new generation seems to rediscover for themselves the trapdoor excitement of the varied theoretical descendants of Marx — and this energy is not entirely misguided: there are many areas in which a constant scrutiny of labor relations is warranted, and the allure of consumerist affluence is far from benign. But a pure materialist interpretation of overload culture severely limits our responses, leaving us, if you’ll excuse some mild facetiousness, with only the option to occasionally engage in non-instrumental activities as an act of resistance while waiting for others to overthrow the capitalist market economy.

I beleive we can do more right now.

My thinking in this area is still half-formed, but I’ve become increasingly convinced that what this conversation needs are alternative definitions of “productivity” that believably deliver on the promises of profitable value generation in businesses and resilient satisfaction in our personal lives, while rendering the excesses of overload culture as unnecessary at best, and profoundly harmful at worse.

In my research on such matters, I’ve come to learn that a lot about how we work and live right now is more ungrounded and arbitrary than many might assume, driven more by a novel mix of autonomy and ambiguity than deterministic dynamics of exploitation. We may need a slow productivity revolution more than we need an economic revolution.

I don’t know exactly what these new definitions of productivity might look like, but we can certainly do better than our current haphazard approaches, in which work descends into performative busyness on Slack, and our personal lives are digested into air-brushed social media moments. The human attraction toward some notion of productivity isn’t the problem. The real issue is neglecting to figure out what specific notions actually make sense for our current moment.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.March 31, 2021

In Defense of Thinking

I recently came across a Hemingway quote that caught my attention:

“My working habits are simple: long periods of thinking, short periods of writing.”

It reminded me of a time I used to spend each spring as a young professor, back when my schedule allowed it, giving short talks at so-called “dissertation bootcamp” events. The point of these multi-day affairs was to help graduate students gain some momentum on their doctoral theses. I would stop by to talk about productivity and focus, and when possible, grab a free lunch.

Attending these bootcamps, I was often struck by how much the conversation centered on “writing.” The informal advice passed around was about “getting in your writing hours,” or making sure “to write every day,” or committing to “hit your target word count.”

I always found this somewhat confusing, as my experience with writing — both popular and academic — matched Hemingway’s self-description, in that the actual act of putting words on the page came only after many more hours spent thinking through what I wanted to say. This contemplation was where the real intellectual action was to be found.

Part of the disconnect, I eventually became convinced, comes from the reality that we’ve lost our familiarity with the concept of “thinking” as a concrete and isolatable activity; something that can be prioritized, and trained, and even cherished as a valuable pursuit in its own right.

In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle identified rational contemplation as the highest and best of all human activities. In The Intellectual Life, Thomastic scholar Antonin-Gilbert Sertillanges spends over 200 pages detailing how the serious thinker should organize their process of thinking.

Today, we’re not nearly as comfortable with this most fundamental of activities. We talk a lot more about information — how we can get more of it, how we can spread it faster — than we do its processing.

We see this in education systems built more around content than training the meta-activity of making sense of content. We see this in a techno-media landscape that emphasizes expression over cogitation, and tribal Sophism over Socratic grappling.

In his 2009 modern classic, Shop Class as Soulcraft, Matt Crawford argued that we were overlooking the ennobling nature of skilled manual work. I increasingly believe a similar manifesto could be penned about our lost appreciation of thinking.

There’s a great satisfaction and steadiness in the general application of Hemingway’s advice. We cannot make sense of ourselves or the world around us without putting in the mental cycles necessary to wrestle this frenetic information into useful forms. Thinking — true, hard, energizing thinking — is not yet another healthy activity to add to a long list of such commitments. It’s better understood as a way of life; one that’s become even more radical in an increasingly shallow world.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.March 23, 2021

On Robert Heinlein’s Analog Autoresponder

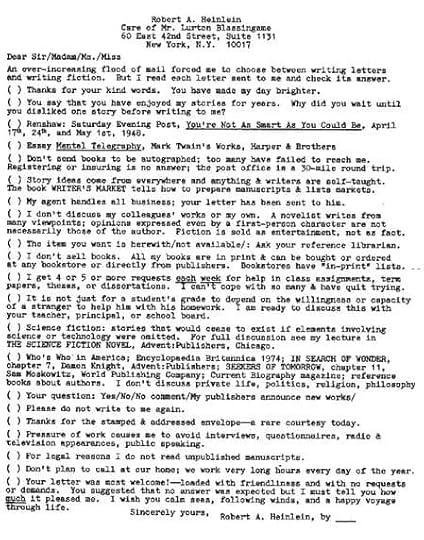

A reader recently pointed me toward a fascinating post on Kevin Kelly’s CT2 blog. It concerned the fan mail received by the famed science fiction author Robert Heinlein. Unable to keep up with the deluge of incoming correspondence, Heinlein devised a form letter (pictured above), which included responses to twenty-one common questions and requests.

These canned replies include, for example, a pointer to the book Writer’s Market for more information on how to prepare manuscripts for submission, and an apologetic note explaining that Heinlein is unable to participate in class assignments. (I empathize with this last one. I’m honored by the surprisingly large number of classes that assign my books or articles, but to my regret, I rarely have enough time to participate in evaluating this work.) To answer fan mail, Heinlein would simply check the box on the form letter next to the most appropriate response.

If we fast forward a few decades later, we find a further refinement on this idea from Neal Stephenson, a literary descendent of Heinlein, who stopped these messages before they arrived by posting an essay on the “contact” page of his website that explains why you shouldn’t bother trying to bother him. It’s called “Why I’m a Bad Correspondent,” and it includes one of my all-time favorite passages about communication:

“If I organize my life in such a way that I get lots of long, consecutive, uninterrupted time-chunks, I can write novels. But as those chunks get separated and fragmented, my productivity as a novelist drops spectacularly. What replaces it? Instead of a novel that will be around for a long time, and that will, with luck, be read by many people, there is a bunch of e-mail messages that I have sent out to individual persons, and a few speeches given at various conferences.”

The rules by which we communicate have a big impact on our ability to do useful work. Too often we just accept whatever seems standard or easy in the moment. It’s nice to remind ourselves that not everyone accepts this fate.

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.March 18, 2021

Combating Zoom Overload with Reverse Meetings

In a recent episode of my podcast, I dove deep on the topic of meeting overload during our current moment of pandemic-induced remote work. I want to expand here on one of the more radical (but intriguing) solutions I mentioned: the reverse meeting.

First, a little background. Why are we suddenly spending so much more time in meetings now that we’re working from home? There are multiple factors involved.

For example, the sudden shift out of the office created a lot of unexpected new questions that had to be answered. In the moment, scheduling a meeting is an easy way to relieve the anxiety of having these new and pressing demands on your plate.

(Remember: the one productivity system that is universally trusted is the calendar, so if a meeting related to a new issue is scheduled, you can trust that it won’t be forgotten, and you therefore no longer have to keep track of it in your head. This grants immediate relief.)

Another factor is a reduction in the energy and social capital expended when organizing online gatherings. Pre-pandemic, setting up a meeting meant reserving a conference room and requiring your colleagues to physically relocate themselves at your request. There’s enough of a cost here that you might think twice before casually convening these conversations.

In a remote setting, however, we’re all just on our laptops all day anyway, so the cost of shooting off a digital calendar invite for a Zoom discussion is much lower. It takes only a couple clicks and the social consequences seem minimal. The result: we setup many more meetings.

This brings us to the question of how to reduce this overload, and therefore back to the idea of reverse meetings. Here’s the concept:

Everyone maintains regular office hours: set times each week during which they’re always available via video conference, chat, and phone. During these times you can digitally stop by and chat without a prior appointment. (For more on office hours, see this excerpt from A World Without Email on the topic.)If you have a topic you want to discuss with a group of your colleagues, instead of gathering them all together in a new meeting, you instead visit each of their office hours one-by-one to talk it through.In many cases, these one-on-one conversations should be sufficient for you to reach a resolution on the issue, or at the very least, reduce it down to a very targeted set of questions that can be much more efficiently addressed.The attention economics of reverse meetings can be much more favorable than our current standard. Consider, for example, a hypothetical scenario where I need to make a decision on a new marketing campaign and need feedback from five of my coworkers. The easy solution is to schedule a meeting to discuss. Let’s say it takes about an hour. This eliminates six people hours — 360 total minutes — of potential attention.

In a reverse meeting scenario, by contrast, I might take only 10 minutes from each colleague, taking up 50 minutes total of my time, and 50 minutes total of their time, for an overall demand of 100 minutes of attention, which is 3.6 times less cost.

As an added bonus, the reverse meeting also reverses the asymmetric consequences of these gatherings. It is now significantly more costly to initiate a meeting than it is to attend. The result? Less meetings are convened in the first place.

There are, of course, many scenarios where this approach doesn’t work, and there are many other strategies that might also help reduce meeting overload. (Another favorite of mine is the meeting quota: each person has three afternoon slots every day for meetings, and that’s it; so once you’ve filled the slots for a given day you have to move on to another day, enforcing an artificial scarcity on collaborative attention and ensuring enough focus is left over for other types of work.)

The broader point, however, is that we need to respond to the current moment with more radical thinking about how we organize our work. For if not now, when?

The post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

March 15, 2021

One Step Closer to a World Without Email

My new book, A World Without Email, was released two weeks ago. I’m pleased to announce that it was an immediate New York Times bestseller, so I want to thank you, my long time readers, for supporting this launch.

I thought before I return to my regularly scheduled programming (trust me, I’m eager to start writing on topic others than just email), it might be useful to round up a few of the more interesting articles and interviews about the book from the launch week.

So here we go…

Featured Articles Written By Me“Email is Making Us Miserable,” The New Yorker“Email and Slack Have Locked Us in a Productivity Paradox ,” WIRED“Had It With Email? Give Personal Office Hours a Try,” Fast Company“Stop Giving Clients Your Personal Email. Here’s Why,” EntrepreneurFeatured Reviews“The Battle with the Inbox,” Wall Street Journal“Email Broke the Office. Here’s how to Fix It.” GQ“Technology has Turned Back the Clock on Productivity,” The Financial Times“The Scourge of Work Email is Far Worse Than You Think,” The Financial Times“Can we really banish email from the workplace? Author Cal Newport says yes,” Fortune“How to drastically reduced the time you spend on emails,” Fast Company“The Man Who Thinks We Should Ignore Our Email,” The Sunday Times“A World Without Email by Cal Newport review — overthrowing the tyranny of email,” The Times of LondonFeatured InterviewsThe Ezra Klein ShowThe Lex Fridman PodcastNPR: Innovation HubRisingThe James Altucher ShowThe Art of ManlinessThe RealignmentBiggerPocketsThe post Blog first appeared on Cal Newport.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers