Cal Newport's Blog, page 16

October 14, 2020

My New Planner + The Time Block Academy

Longtime readers and recent podcast listeners know that I’m a massive advocate of a productivity technique called time-block planning, which is at the core of my strategy for getting important things done in an increasingly distracted world.

After years of hand-formatting generic notebooks to satisfy my time-block planning needs, I decided to design my own planner optimized for exactly this activity.

Here’s the result…

The Time-Block Planner will be available everywhere books are sold online on November 10th and can be pre-ordered today.

I’ll share more details on the planner and the method it encodes as we get closer to the publication date. In the meantime, however, I wanted to discuss a special event I’m organizing for those hardcore time blockers who pre-order the planner before November 10th.

The event is called Time Block Academy.

It’s a live Zoom webinar that will be held November 13th at 3pm eastern. During the event, I’ll answer both live and pre-submitted questions about time blocking, productivity more generally, or whatever else is on your mind — sort of like a live episode of Deep Questions attended by a select crowd.

To gain admission, pre-order the Time-Block Planner at your preferred retailer, and email your proof of purchase to timeblockplanner@prh.com. My publisher will email you back with details about the webinar, as well as a link to a video tutorial I created that gives you a sneak peak of the planner and how it works.

(US Residents, 18+. Ends November 09, 2020. See terms at this link.)

The post My New Planner + The Time Block Academy first appeared on Cal Newport.

October 5, 2020

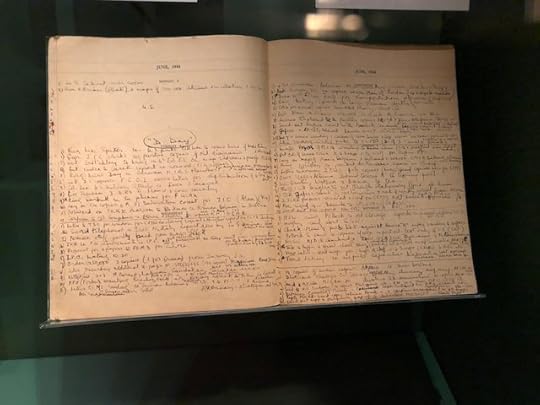

Churchill’s D-Day Task List

Last week, I received an email from a reader who had just returned from a trip to the Churchill War Rooms, a London museum housed in the bunkers, built underneath the Treasury Building, where Winston Churchill safely commanded the British war efforts as the Blitz bombarded the city above.

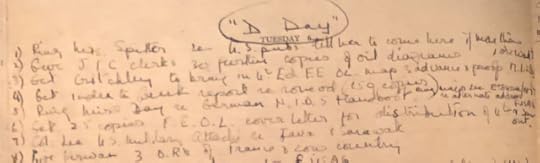

The reader had photographed an artifact he thought I might find interesting: a to-do list labeled “D Day,” written by one of the secretaries serving Churchill.

Here’s a detail shot:

Superficially, I was intrigued because I’ve been consuming a lot of WWII history recently. (At the moment, I’m concurrently reading The Splendid and the Vile along with David Roll’s excellent new George Marshall biography.)

But it also resonated at a deeper level.

On my podcast, I’ve been talking a lot about the notion of “facing the productivity dragon.” The idea is that when you’re confronted with a seemingly untenable set of obligations — as so many are right now during these pandemic times as jobs disappear, or force us to somehow juggle mounting work responsibilities with closed-school childcare — it’s still best to enumerate the full scope of the challenge.

Don’t retreat into frustration and despair. Write down everything that’s demanded of you, even if you can’t possibly satisfy all of the obligations. Then make the best plan you can given the difficult circumstances. The comfort comes from the plan, not the achievable outcomes.

Face the dragon, in other words, even if it’s terrifying. You’ll end up calmer and with more resolve than those who flee.

This is what came to mind when I looked at the above artifact images from the Churchill War Rooms. Even when forced to deal with something as hopelessly complex, and fraught, and impossible, and insanely high stakes as the reconquest of Europe, the first step was to write down, in humble script, the full scope of the tasks required for such an overwhelming endeavor.

You cannot slay the dragon until you can see it.

The post Churchill's D-Day Task List first appeared on Cal Newport.

September 29, 2020

On the Neurochemistry of Deep Work

Andrew Huberman is a neurobiologist at Stanford Medical School. His lab specializes in neuroplasticity, the process by which the human brain changes its neuronal connections.

A reader recently brought to my attention a fascinating discussion about learning. It’s from a podcast episode Huberman recorded with Joe Rogan back in July.

Around the two minute mark of the clip, Rogan provides Huberman with a hypothetical scenario: “You’re 35, and want to learn a new skill, what is the best way to set these patterns?”

As someone who is in my thirties and makes a living learning hard things, I was, as you might imagine, interested to hear what Dr. Huberman had to say on this issue. Which is all to preface that I was gratified to hear the following reply:

“If you want to learn and change your brain as an adult, there has to be a high level of focus and engagement. There’s no way around this…you have to lean in and focus extremely hard.”

As longtime readers know, I made this same argument in Deep Work, where I noted that “the ability to learn hard things quickly” was one of the two main advantages of training your ability to concentrate.

But Huberman blows past my simplistic explanations and dissects the complex neurochemistry behind learning. I won’t try to replicate all the details of his impromptu lecture, but I’ll elaborate one particularly interesting point.

Huberman notes that to attain significant brain rewiring requires that you induce a sense of “urgency” that leads to the release of norepinephrine. This hormone, however, will make you feel “agitated,” like you need to get up and go do something. It’s here that you must apply intense focus to fight that urge, ultimately leading to the release of acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter that in combination with the norepinephrine can induce brain growth.

I’m probably bastardizing some of these biological details, but regardless, they point to a narrow example of a broader point. The ability to focus is more than just an anachronistic novelty. It’s at the core of how us humans adapt and thrive in a complex world.

#####

Speaking of Deep Work, as I write this, it’s currently one of Amazon’s Daily Deals, meaning that the Kindle version is available for only $3.99. If you haven’t yet taken a deep dive into deep work, now is a great time to do so!

The post On the Neurochemistry of Deep Work first appeared on Cal Newport.

September 22, 2020

Do Smartphones Make Us Dumber?

A reader recently pointed me toward an intriguing article published in 2017 in the Journal for the Association of Consumer Research. It was titled, “Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity.”

The authors of the paper report the results of a straightforward experiment. Subjects are invited into a laboratory to participate in some assessment exercises. Before commencing, however, they’re asked to put their phones away. Some subjects are asked to place their phone on the desk next to the computer on which they’re working; some are told to put their phone in their bag; some are told to put their phone in the other room. (The experimenters had clever ways of manipulating these conditions without arousing suspicion.)

Each subject was then subjected to a battery of standard cognitive capacity tests. The result? Subjects measured notably lower on working memory capacity and fluid intelligence when the phone was next to them on the desk versus out of sight. This was true even though in all the cases the subjects didn’t actually use their phones.

The mere presence of the device, in other words, sapped cognitive resources. The effect was particularly pronounced in those who self-reported to be heavy phone users.

I think we’re only scratching the surface on the damage caused by our current technology habits. As I argued in Digital Minimalism, these tools are both powerful and indifferent to your best interests. Until you decide to adopt a minimalist ethos, and deploy technology intentionally to serve specific values you care about, the damage it inflicts will continue to accumulate.

The post Do Smartphones Make Us Dumber? first appeared on Cal Newport.

September 16, 2020

Eric Posner Thinks It’s a “Serious Mistake” for Law Professors to Use Twitter

Eric Posner is arguably one of the most influential and prolific law professors in the country at the moment. Which is why I paid attention when around the 39 minute mark of a recent interview, Posner was asked his thoughts on law professors using Twitter.

“I’ve thought about this a lot because it now seems like every law professor wants to have this public presence,” Posner replied. “And I increasingly think this is a serious mistake.”

As he elaborates, becoming a “good” academic who is “serious” about research is a hard job:

“It requires a huge amount of work, especially at the beginning, to absorb the literature, to absorb the norms…I think a lot of junior people who are on Twitter…should be educating themselves.”

As he then clarifies, most of what transpires on Twitter is people “ranting” and reading other peoples’ “rants.” Participating in that culture, he says, doesn’t contribute in a meaningful way to the public debate.

The interviewer then presents Posner with another standard argument for why academics should engage with social media: it’s a way to “establish prominence in a field or establish name recognition.”

Posner doesn’t buy it:

“They’re wrong. You see. It’s a classic mistake. They don’t realize that everyone else is thinking that as well…you think you’re going to get name recognition, and you’ll get known, because you’re sending out these really clever and incisive tweets that are going to get the attention of the world. But you’ve forgotten that a thousand other people are doing exactly the same thing.”

As Posner elaborates with acid precision, his experience with Twitter taught him that what it’s really good at is “tricking” you into thinking that “the whole world is waiting for you to pronounce on some important issue.” This sense of importance is intoxicating. But as he argues, with the exception of a very small number of outliers, the audience for most users doesn’t extend far beyond bots and some friends.

Even I don’t fully escape Posner’s derision, as he also briefly mentions blog posting as a similar waste of time. (The irony!) But I think it’s his take on Twitter that rings particularly true. I wrote some about this “illusion of influence” concept in Deep Work. These services don’t hook you because they’re interesting; they hook you because they make you feel like you’re interesting.

Which is all well and good, until you look up five years later at your tenure review and lament about all the high impact papers you could have written instead.

The post Eric Posner Thinks It's a "Serious Mistake" for Law Professors to Use Twitter first appeared on Cal Newport.

September 11, 2020

Michael Connelly Starts Writing Before the Sun Comes Up

One of the notable realities of my life, given the topics I write about, is the regularity with which people send me various articles about the work habits of the novelist Michael Connelly. Here’s a representative sample from an interview published in The Daily Beast:

“I get up to write while it’s still dark, 5 or 5:30. I start by editing and rewriting everything I did the day before, and that gives some momentum for the day. I get to new territory when the sun is coming up. I take a break to take my daughter to school…then I get back to it. If it’s early in a book, I’ll only write til lunch, because it can be hard for me to get that momentum going. If it’s late in a book and really flowing, I’ll just keep writing and writing until I’m either too tired or have been called to dinner.”

He later elaborates that he uses blackout shades to transform his writing office into a space beyond time. “You don’t know if it’s light or dark,” he explains. “I just try to put everything else out of focus and look only at the screen of my laptop.”

This routine is common among popular genre fiction writers (see, for example, John Grisham or Lee Child). To fulfill the economic necessity of publishing one book per year — which, as I can tell you from experience, is really hard — they strip down their work habits to support maximum cognitive output.

For the rest of us, drowning in our inboxes and Zoom invites, this should be more than a source of aspirational escape. It represents a reminder that getting the most out of the messy jumble of neurons known as the human brain requires sacrifices. To instead orient work around pleasing everyone who might need you in the moment is to ultimately please no one with the quality of what you produce.

The post Michael Connelly Starts Writing Before the Sun Comes Up first appeared on Cal Newport.

August 31, 2020

Life of Focus: Now Open

The first session Life of Focus, the online course I created with Scott Young, is now open. The registration period will last until Friday, September 4th (midnight Pacific Time).

As I elaborated last week, this course is designed to help you transform both your professional and personal lives so that you focus more on things that really matter, and spend less of your day mired in distractions that don’t. It will then help you train your brain to make the most of the time you put aside for these important pursuits.

Drawing on ideas first explored in our bestselling books, Deep Work, Digital Minimalism, and Ultralearning, the course is divided into three months, each built around a concrete project that pushes you forward in your transformation into a life of focus. You’ll be guided in these efforts by video lessons, worksheets, and community support from your fellow students.

We’re proud of this course. We’ve been working on it for well over a year and have integrated into its construction the hard-won experience gained from serving over 5,000 students in our last online offering, Top Performer.

You can find out more details about the course and register here.

We’ll be closing registration on Friday. I hope to see you in the course!

(And if this is not of interest, worry not: this is the last blog post you’ll see about this session of the course. I will be sending some more information to my email list this week, but I’ve added a link to these emails that allows list subscribers to easily opt-out of receiving these course-related emails.)

The post Life of Focus: Now Open first appeared on Cal Newport.

August 29, 2020

Focus Week: Take Control of Your Time

In the first lesson of our Focus Week series, I suggested that you unplug to give your brain and emotions a breather in our current moment of constant, agitating distraction. In the second lesson, I suggested that you implement a daily deep reading habit to retrain your neural networks to sustain and find satisfaction in unbroken concentration. In this third and final lesson, I want to talk about how to leverage this newly reclaimed clarity to focus your life.

At the heart of my advice is a simple recommendation: take control of your time. To be more concrete, when thinking about your work day, I suggest that you give every minute a job.

I call this technique “time blocking,” and I’ve been talking about it here since at least 2013. I also popularized it in my book, Deep Work, discuss it often on my podcast, Deep Questions, and am even releasing a planner dedicated to the method in November. Which is all to say: I’m a fan of this strategy.

Here’s the basic idea…

Most people tackle their work day using what I call the list/reactive method. This casual approach has you fill the time between scheduled meetings and calls reacting to emails and occasionally, when the mood hits you, trying to make progress on items plucked from an unwieldy task list.

The time blocking method, by contrast, has you partition your days into blocks of time and assign specific work to these blocks. Maybe, for example, you’re working on a strategy memo from 9:00 to 10:00, then after a 10:00 to 10:30 meeting you put aside thirty minutes for checking email, followed by ninety-minutes, from 11:00 to 12:30, when you’ll try to complete a project report that’s due soon, and so on. Every minute gets a job. (What if you get knocked off your schedule by an unexpected crisis or task that takes longer than expected? Not a problem. You just build an updated time block schedule for the remainder of the day the next time you get a chance. The key is maintaining intention about your time, not perfection in your planning.)

There are two problems with the list/reactive method. First, because you’re letting other peoples’ needs drive your activities, the balance between the urgent and the important becomes skewed. You feel busy and exhausted, but you’re not really moving the needle on the things that matter.

Second, because you have no plan beyond just “trying to get things done,” it’s easy for your mind to keep deciding it needs ad hoc internet “breaks,” which have a way of transforming into time-devouring rabbit holes. This decreases the total amount of work you’re able to accomplish.

Time blocking, by contrast, gives you fine-grained control over the balance between the urgent and the important. In addition, because you know what you’re supposed to be doing at any given moment, you’re much less likely to take unplanned breaks. Time blockers, in other words, don’t web surf.

This scheduling commitment also provides you hard evidence on how much time you really have available, and how long things really take. This reality check can be bracing at first, but ultimately it’s crucial. It leads to a more vigorous essentialism (e.g., as I recently discussed on Greg McKeown’s podcast), and more conservatism on how early you start projects.

A word of warning, however, is that this strategy is cognitively demanding. Part of the reason time blockers get so much more done is because their average intensity of focus is quite high compared to their semi-distracted peers. Such concentration, however, takes a toll. So you do not want to extend this blocking discipline to your time outside of work, as this excessive rigidity will eventually lead to burn out.

Escaping from the noise of a distracted world and becoming reacquainted with the pleasures of presence and concentration are crucial preconditions to a focused life. To achieve this state in full, however, ultimately requires that you take the final step of actually focusing your attention with intention and purpose.

Time block planning will move you in this direction. It’s important to note that it’s not enough by itself. A life of focus also needs, for example, regular time to reflect about what to focus on in your work, and a more serious commitment to directing your free time toward higher quality and more rewarding activities. Beyond these concerns, solitude is important, as is aggressive community engagement and cultivating high quality leisure.

But time blocking will set the needed tone; a signal to yourself that you take seriously how you direct your newly empowered attention.

####

If you’re looking to go beyond the advice offered in this Focus Week series, and take even more radical action toward reclaiming your life from the forces of distraction, then I invite you to stay tuned to find out more about Life of Focus, the new online course that I co-created with Scott Young.

The course takes students through a three-month, guided training. The first month is about gaining more focus in your work life, the second month is about increasing focus in your life outside of work, and the third month is about training your brain to focus at levels of intensity that enable astounding feats of cognitive accomplishment.

We’re opening the course for registration on Monday, August 31st. I’ll post a note on my blog and email newsletter on Monday pointing you to where you can learn more.

I hope to see you in the course. But regardless, hopefully this week has already injected a new appreciation of focus in your life. Stay deep!

The post Focus Week: Take Control of Your Time first appeared on Cal Newport.

August 27, 2020

Focus Week: Rediscover Depth

When I was a young graduate student at MIT, I was impressed by Alan Lightman, a one-time physicist, who turned toward essay and novel writing and ended up accepting a humanities professorship and starting the school’s science journalism program.

What initially caught my attention about Lightman was the following line, which to this day remains defiantly perched at the top of his academic homepage:

“I do not use e-mail, but you can reach me at my MIT office: [mailing address]”

But what really captured my imagination was when I heard about Lightman’s island.

In his late 30’s, at a time when the was looking for a quiet place for him to write and his wife to paint, Lightman stumbled across a 30-acre island in Casco Bay, Maine, shared by six families. There are no bridges or ferries servicing the island; no electricity; no plumbing; no internet or phone. Lightman and his wife spend their summers at this isolated outpost decompressing and creating.

“The world is moving at much too fast a pace: everybody is plugged in 24/7, everything is rush rush rush,” he said in a recent interview. “The island in the summer is a place where we can unplug, slow down, listen to ourselves think.”

I was reminded of Lightman while recently reading about Mary Somerville, the 19th century polymath who was among the first women to be elected to the Royal Astronomical Society. As Somerville recalls in her autobiography, as a child, she would find ways to evade the chores and social activities that defined the lives of women of her social station to instead explore the nearby sea coast:

“When the tide was out I spent hours on the sands…I made collections of shells, such as were cast ashore, some so small that they appeared like white specks in patches of black sand. There was a small pier on the sands for shipping limestone brought from the coal mines inland. I was astonished to see the surface of these blocks of stone covered with beautiful impressions of what seemed to be leaves; how they got there I could not imagine, but I picked up the broken bits, and even large pieces, and brought them to my repository.”

Her collection, begun during those childhood expeditions, is now housed at the college named in her honor at the University of Oxford.

Lightman and Somerville’s lives were defined and elevated by regular exposure to depth: extended periods of undistracted time during which the mind can focus intensely on one thing, or purposefully on nothing at all. In both cases, this depth was hard-won. Lightman’s island was remote and offered primitive living conditions. He had never used a boat before committing to a house that required one to access. Somerville, for her part, had to battle the gender expectations of her era to carve out a deeper life. It never came easy.

But they invested the effort because, as I argue in Deep Work, we can find evidence from psychology, neuroscience, philosophy and theology that all supports the same conclusion: humans thrive on concentration and presence.

Which brings us to the last five months: a period in which such moments of depth were lost to the daily waves of anxiety and uncertainty.

In my previous Focus Week essay, I recommended unplugging to provide your brain some breathing room. Here I’m recommending that you put this breathing room to good use by reintroducing yourself to the pleasures of concentrating without distraction on something difficult but rewarding; to rediscover, in other words, the necessity of depth.

There are many ways to execute this reintroduction. For the sake of concreteness, here is one specific strategy among many that I’ve found to be effective: read two chapters from a book every day; with at least one of the chapters read in a scenic or otherwise interesting setting.

If you’ve been splashing in a world of distracting shallowness since March, you may need to ease back into regular engagement with complicated material. I would suggest starting with books that are easy to read, such as popular novels, or narrative non-fiction, or advice writing. As you complete each book, however, raise the difficulty of the next. Your goal is to get to a place where the two chapters consumed each day really push your mind.

(In my own practice of this discipline, for example, which I started over the summer, I’m currently working on the famed Harvard classicist Gregory Nagy’s 600-page tome, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours.)

The addendum about finding a scenic or interesting location is meant to help your brain ritualistically context shift. This will help your concentration and increase the satisfaction of the exercise. A nearby park works well for this purpose. If you have access to woods, especially woods with a stream, that’s even better. Sitting outdoors at a cafe can be equally effective. The goal is to distinguish the activity from everyday life, providing that moment of presence enjoyed by Lightman on his island or Sommerville by the seashore.

Finding time to read is not easy, especially for those of us juggling remote work with a lack of childcare. You might have to use early mornings, or late evenings, or 20-minute”meetings” put on your shared work calendar that secretly protect time for you to dash outside and knock off some mid-day pages. The specific quantity of two chapters was selected to be easy enough that most people can fit it in most days, but hard enough that it still generates a benefit.

It’s important to emphasize that this commitment is no indulgence. You cannot exist in a persistent state of agitated distraction. A regular dose of depth will do more than provide you a fleeting moment of calm, it will begin a more lasting process of rewiring your brain back toward a state of concentration, and insight, and creativity that’s much more compatible with a satisfying and meaningful life, even in times of struggle.

The post Focus Week: Rediscover Depth first appeared on Cal Newport.

August 25, 2020

Focus Week: Give Your Brain Some Breathing Room

I opened my book Digital Minimalism with an excerpt from an Andrew Sullivan essay, published in New York magazine in 2007. “An endless bombardment of news and gossip and images has rendered us manic information addicts,” Sullivan warned. “It broke me. It might break you, too.”

I noted that Sullivan’s experience as a burnt out professional blogger was extreme, but that a diminished echo of his distress was beginning to spread through a culture increasingly glued to its phones. Over the past five months, this diminished echo has exploded into full out replication. We no longer just feel hints of Sullivan’s distress; we’re living it completely.

The anxious uncertainty of the pandemic, combined with social and political unrest, combined with an information landscape dominated by a tribalized social media, is breaking us. Our days are fragmented by a fast drip of insistently panicked content that wrings anxiety, outrage, and fear from our autonomic nervous systems until we’re left exhausted and emotionally dry.

If you’ll excuse the understatement: this is not good.

It is with these observations in mind that I think a fitting place to start Focus Week is with an urgent plea to unplug — to allow the fragments of your attention to coalesce back into meaningful stretches of presence, and your emotions to re-stabilize. You cannot reclaim a life of focus until you reclaim your brain from the distractions that have ensnared it in recent months.

I have two concrete pieces of advice to offer. The first concerns news consumption. To abstain from all information about the world at this current moment would be a betrayal of your civic duty. On the other hand, to monitor every developing story in real time, like a breaking news producer, is a betrayal of your sanity.

I suggest the following compromise: check in on the news for 45 minutes, once a day, preferably in the morning.

You can listen to one of those popular news round up podcasts while you perform chores or go for a morning walk. You can browse the main headlines of a newspaper. You can have the radio news on in the background while you make breakfast.

If there’s a hurricane heading your way, this is your moment to check on the latest cone of uncertainty from the National Hurricane Center. If there’s an activist cause in which you’re engaged, this is the time to check in on the writers or publications whose work on the topic you admire.

Do not watch cable news. Do not look to Twitter. It’s better, if possible, to find sources that do not so directly attempt to access your amygdala.

It’s important to recognize that many people find value from social media that goes beyond the news, such as inspiration or connection. During this current moment, however, these services must be treated with particular care. Which brings me to my second piece of unplugging advice: remove all social media apps from your phone; isolate the browsing of these services to a set period of time in the evening; avoid angry posts.

Do not allow these tools to become a background source of diversion that you turn to throughout your day. Access them instead only on your computer, only during a set time (perhaps one hour each evening). Be intentional about what you browse: focusing on the positive, and avoiding posts whose primary goal is to get you angry, or deliver the Faustian satisfaction of watching your team dunk on the other.

To summarize, in my proposed scheme, you engage with the world of digital information only twice a day: once in the morning, and (perhaps) once in the evening. Outside these brief moments of anxious consumption, you focus instead on living well.

Give your work the concentration it needs, be present with your family, rediscover the hard-won joys of high quality leisure, even experience those necessary moments of gratitude, once common during the lazy heat of late summer, but more recently lost to the insistent growl of the glowing screen.

You cannot reclaim a life of focus when you’re wallowing in a stream of insistent negativity. Learn what you need. Recognize its gravity. Then get on with living deeply.

The post Focus Week: Give Your Brain Some Breathing Room first appeared on Cal Newport.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers