Cal Newport's Blog, page 17

August 23, 2020

Returning to a Life of Focus

Last fall, Scott Young and his team flew down to Washington D.C., to join me in a Capitol Hill film studio to begin production on the long-awaited sequel to our popular Top Performer online course. Whereas that previous course helped people take action on the career advice from my book So Good They Can’t Ignore You, this new course was motivated by the ideas explored in the trio of bestsellers on concentration and distraction that Scott and I have published in the years since: Deep Work, Digital Minimalism, and Ultralearning.

We decided to call it: Life of Focus.

When production began, we had no way of predicting the upheaval the world was going face just a few months later due to the coronavirus pandemic. As we put the finishing touches on the course over the spring and into the summer, it became clear that the need to reclaim a life of focus had suddenly become perhaps more important than any time in recent memory.

The world is mired in disruption and distraction. The past six months have been defined by a constant, unrelenting, emotionally-draining stream of news, and clips, and tweets, and texts competing with the frantic emails and endless Zoom meetings generated by a knowledge economy haphazardly stumbling into a virtual format.

We’ve lost solitude. We’ve lost a sense of control over our time and attention. We’ve lost the ability to read a hard book, or think through a complicated thought, or enjoy a quiet moment. We’re lost in a world of screens.

It’s time to push back.

When thinking about when to launch Life of Focus, Scott and I decided that August 31st would be the perfect date. On the calendar, it marks the end of summer, and the return to more serious work. Symbolically, it also marks the point where the urgency and novelty of the pandemic has ebbed, and the time has come to figure out how to adjust to a less than optimal new normal.

Not everyone, of course, is interested or able to take an online course. To reach a larger audience with this concept of reclaiming your your life this fall, I plan to publish a series of three posts this week that outline a DIY curriculum for shifting from a life of distraction back to a life of focus — in work and at home.

I call it “Focus Week.” And I couldn’t think of a more important time to tackle this topic.

The post Returning to a Life of Focus first appeared on Cal Newport.

August 20, 2020

Ray Bradbury Got It Exactly Right

Ray Bradbury’s short story, The Murderer, first published in his 1953 collection, The Golden Apples of the Sun, begins with a psychiatrist arriving at a mental hospital. He’s there to see a prisoner named Albert Brock, who calls himself: “The Murderer.”

When the psychiatrist enters the interview chamber, he frowns. “Something was wrong with the room.” He soon realizes the problem: the wall-mounted radio has been torn down and smashed.

As the psychiatrist sits down, Brock reaches out and quickly steals the visitor’s wrist radio, crunching it in his teeth like a walnut, before handing back the ruined device with a smile, explaining: “That’s better.”

It’s soon revealed that Brock is not imprisoned because of any harm he caused to other people. His crime was instead the wanton destruction of all the information, entertainment, and communication devices in his life: he fed his phone into his kitchen garbage disposal, shot his television with a gun, poured water into his office intercommunication system, stomped his wrist radio on the sidewalk, and spooned ice cream into his car’s FM transceiver.

As Brock elaborates, he’d become fed up with the constant communication, distraction, manipulation and digital anxiety that defined the near future world in which Bradbury’s story is set:

“It’s easy to say the wrong thing on telephones; the telephone changes your meaning on you. First thing you know, you’ve made an enemy. Then, of course, the telephone’s such a convenient thing; it just sits there and demands you call someone who doesn’t want to be called. Friends were always calling, calling, calling me. Hell, I hadn’t any time of my own. When it wasn’t the telephone it was the television, the radio, the phonograph…When it wasn’t music, it was interoffice communications, and my horror chamber of a radio wristwatch on which my friends and my wife phoned every five minutes.”

These changes were not the result of an Orwellian imposition, but had instead emerged naturally; unexpected cultural side effects of innovations that were celebrated when first introduced:

“It was all so enchanting at first, the very idea of these things, the practical uses, was wonderful. They were almost toys, to be played with, but the people got too involved, went too far, and got wrapped up in a pattern of social behavior and couldn’t get out, couldn’t admit they were in, even.”

It becomes clear that the psychiatrist cannot relate. “Can I go back to my nice private cell now, where I can be alone and quiet for six months?”, Brock finally asks.

Confused, the psychiatrist heads back to his office, where he renders his dismissive prognosis: “Seems completely disoriented, but convivial. Refuses to accept the simplest realities of his environment and work with them.”

He recommends commitment of an “indefinite” length, before his attention is drawn away:

“Three phones rang. A duplicate wrist radio in his desk drawer buzzed like a wounded grasshopper. The intercom flashed a pink light and click-clicked. Three phones rang. The drawer buzzed. Music blew in through the open door. The psychiatrist, humming quietly, fitted the new wrist radio to his wrist, flipped the intercom, talked a moment, picked up one telephone, talked, picked up another telephone, talked, picked up the third telephone, talked, touched the wrist-radio button, talked calmly and quietly, his face cool and serene, in the middle of the music and the lights flashing, the phones ringing again, and his hands moving, and his wrist radio buzzing, and the intercoms talking, and voices speaking from the ceiling…”

All the while, The Murderer relaxes in luxurious silence.

If we could bring Bradbury forward into our current moment, he’d look around, nod his head with resignation, then quip: “Yep. This looks about right.”

August 17, 2020

George R. R. Martin’s Pandemic Writing Retreat

As discussed in a blog post published earlier this week, Game of Thrones scribe George R. R. Martin is trying to take advantage of the pandemic to help finish The Winds of Winter, the long awaited (and long overdue) next title in his epic fantasy series.

Years earlier, Martin bought the building across the street from his Santa Fe home to provide some separation between his personal and professional lives (“no longer would I write all day in my red flannel bathrobe”), but more recently he found even that space had become too distracting to properly concentrate.

So he’s now relocated to a remote mountain cabin with a bad internet connection where he can really get serious about writing.

To avoid needing to make his own coffee, he even has poor assistants — whom he regrettably calls “minions — take two-week shifts at the cabin. Because Martin is not exactly a specimen of peak physical fitness, and therefore rightly concerned about Covid, he has them self-quarantine for two weeks at home before their shifts begin.

Like a gearhead gawking at Jay Leno’s $50 million car collection, I always find it fascinating, if not at times unnerving (minions!?), to read about how rich professional thinkers support concentration when money is no object.

At times like these, I think a lot of us could probably get a lot out of an isolated mountain cabin. Even if we had to make our own coffee.

August 12, 2020

Don’t Delegate Using Email

On the most recent episode of my podcast, Deep Questions, a listener asked for my advice about delegation. This is an important topic that I haven’t talked a lot about before, so I thought it might be useful to sharpen and elaborate the answer I gave on my show.

In the office setting, most delegation occurs over email. You need something done that you either don’t have the time to do, or don’t want to do, or don’t know how to do: so you shoot off a quick message to put in on someone else’s plate. Our current moment of remote work has made these electronic hand-offs even more frequent.

As I explained on my podcast, however, I think this is a problem. You’d probably be better off if you instead worked backward from a simple rule that will make your life more annoying in the short term, but significantly more productive in the long term: don’t delegate using email.

Before we discuss how this is even possible, let’s touch on why it’s important.

When handing off tasks, email’s extreme efficiency can become a liability. It nudges you toward temporary relief of psychic discomfort. You think of something that you don’t want to forget, so you dash off an email: look into this and get back to me! Something new arrives in your inbox, creating a brief moment of obligation — oh no, something else I have to make time for — that can be dispelled with a quick forward of the message to a colleague.

I call this relief temporary, however, because you haven’t actually dissipated the discomfort. A quickly composed, ambiguous delegation email only passes this discomfort onto its recipient, perhaps even increasing the distress, as you’ve likely left out details clear to you, but not to the person grappling with your hasty missive. To make matters worse, this ambiguity will then require many more additional back-and-forth messages to try to approximate some clarity, further multiplying and spreading the cognitive toll of the original task.

When you instead enforce a simple no email delegation rule, this instinct to sacrifice the greater good for a smaller personal respite is stymied. Solutions that are overall more productive suddenly become necessary.

On my podcast, for example, I talk a lot about task board software, like Trello, Flow, or Asana. Instead of allowing tasks to exist implicitly among emails buried in an inbox, why not instead isolate and clarify them as standalone cards on a virtual task board? Now it’s clear who is supposed to be working on what, and all the information relevant to a given task can be appended to its card, instead of fracturing itself among impromptu email threads.

The person doing the delegation must now clarify what exactly they’re delegating. When creating a new card for a task, as opposed to dashing off a message, you’re forced to actually think through and articulate exactly what it is you want, when you need it, and what information will be required to get there.

These tasks boards also make it difficult to escape exactly how much you’re asking someone to do. It’s easy to shoot off a dozen emailed requests to a colleague throughout a busy day without thinking much about it. But when you instead see each card piled on top of another in that person’s column on a task board, the magnitude of what you’ve dispensed is unavoidable.

For quick tasks that arrive in the form of emails, I’ve also found ticketing systems to be useful. This allows messages to be transformed into tickets that can be assigned to specific team members, appended with notes, and labeled with their current status. This is how, for example, in my capacity as the Director of Graduate Studies for my department at Georgetown, I coordinate incoming email issues with my Graduate Program Manager (we use FreshDesk).

I can tell you from personal experience that the extra hassle in the moment of moving questions and requests into this system is absolutely worth it. The added structure of the ticketing system significantly reduces stress as compared to the alternative of attempting to juggle all of these obligations through an amorphous and ever-increasing tangle of undifferentiated emails.

I don’t want to fall too far down a productivity process rabbit hole here. My main observation is that when it comes to delegation, don’t be seduced by the promise of a temporary fix to the momentary crisis of having something new to wrangle. Email doesn’t have enough friction. It’s better to embrace a more structured system for identifying, describing, assigning and reviewing tasks that trades slightly more work right now for a significantly decreased cognitive toll for your organization in the future.

August 5, 2020

On the Subtle Network Science of Optimal Office Communication

Consider the following workplace scenario. The manager of an R&D lab needs her engineers to solve a complex problem. There are many possible approaches and it’s unclear which will end up best. What is the best way to structure their communication?

For at least the last twenty years, the accepted answer to this question within knowledge work has been to introduce the maximum amount of communication with the minimum possible friction. Email makes it simple for engineers to swap ideas and results. Instant messenger tools like Slack reduce friction even further and increase transparency. Progress!

The logic driving this consensus is straightforward: more information is strictly better than less; a veritable axiom of the burgeoning Information Age that has been widely accepted ever since Bill Gates touted his early-adoption of email as a strategy to broaden the incoming stream of ideas and insights on which his algorithmic brain could churn.

But is this answer always right?

Many knowledge work sages may have overlooked a classic 2007 paper from the network science literature. It’s titled “The Network Structure of Exploration and Exploitation,” and it’s authored by two Harvard researchers, David Lazer and Allan Friedman (Lazer has since been hired away to Northeastern’s impressive network science group).

Early in the paper, Lazer and Friedman acknowledge the maximal information consensus:

“Services to increase the efficiency with which we exploit our personal networks have proliferated, and armies of consultants have emerged to improve the efficiency of organizational networks. Implicit in this discourse is the idea that the more connected we are, the better: silos are to be eliminated, and the boundaryless organization is the wave of the future.”

As they elaborate, however, the research supporting this view tended to focus on scenarios that measured individual welfare in solving a problem. In such settings, more connectivity was better, as it ensured that solutions better than your own would diffuse into your awareness as quickly as possible.

Lazer and Friedman, by contrast, were interested in the problem-solving ability of the overall group. The question they asked, in essence, was how the structure of the underlying communication network impacted a group’s ability to come up with the best possible solution to a problem.

The details of the experiment get a little tricky. They used a round-based agent simulation and focused on the NK problem space, a set of abstract problems, introduced by evolutionary biologist Stuart Kauffman, in which “solutions” are modeled as sequence of numbers, and nearby solutions (e.g, those that differ by only a small number of changes) have at most small differences in their fitness values. This creates a “rugged landscape” where you might have to explore worse answers to get to better options.

Lazer and Friedman assumed that individuals were “myopic,” meaning that in a given round they could only examine solutions that were slightly different than their best known current solution. They can also, however, explore their neighbors in the network and discover their best solutions, adopting them if better than their own.

They then studied how different network structures impacted the quality of the best solution arrived at in the network as a whole. To return to our original example, they wanted to know what type of communication network would lead our hypothetical engineers to the best possible outcome.

Here’s a crude summary of their otherwise complex results:

Well-connected networks, in which information flows quickly, arrive at pretty good solutions fast, but then get stuck.

Poorly-connected networks, in which information flows slowly, arrive at much better final solutions, but it takes longer.

This trade-off between quality of final solution and speed at which solutions are reached can be tuned by taking a poorly-connected network and then adding more and more shortcuts to the information flows.

The underlying dynamic behind these results is easy to understand. In a poorly-connected network, more solutions are being examined in parallel before the best of the bunch is able to spread enough to enforce a consensus. In the well-connected network, the first reasonable idea quickly takes over.

I mention this paper to underscore an important reminder. We should be cautious about any early confidence that the way we work today is in any sense optimal. Hooking everyone up to low-friction digital communication channels and telling them to rock n’ roll is flexible, convenient, and cheap. But it might be far from the best approach to taking a collection human minds and extracting from them the best possible results.

We still, in other words, probably have a lot of work to do in figuring out the best way to work.

July 29, 2020

The Bit Player Who Changed the World

In 1937, at the precocious age of 21, an MIT graduate student named Claude Shannon had one of the most important scientific epiphanies of the century. To explain it requires some brief background.

Before coming to MIT, Shannon earned two bachelors degrees at the University of Michigan: one in mathematics and one in electrical engineering. The former degree exposed him to Boolean Algebra, a somewhat obscure branch of philosophy, developed in the mid-nineteenth century by a self-taught English mathematician named George Boole. This new algebra took propositional logic, a fuzzy-edged field of rhetorical inquiry that dated back to the Stoic logicians of the 3rd century BC, and cast it into clean equations that could be mechanically-optimized using the tools of modern mathematics.

Shannon’s degree in electrical engineering, by contrast, exposed him to the design of electrical circuits — an endeavor that in the 1930s still required a healthy dollop of intuition and art. Given a specification for a circuit, the engineer would tinker until he got something that worked. (Thomas Edison, for example, was particularly gifted at this type of intuitive electrical construction.)

In 1937, in the brain of this 21-year-old, these two ideas came together.

Boolean logic, Shannon realized, could be used to transform the art of designing electrical circuits into something more formal. Instead of starting from a qualitative description of a what a circuit needed to accomplish, and then tinkering until you came up with a workable solution, you could instead capture the goal as a logic equation, and then apply algebraic rules to improve it, before finally translating your abstract symbols back into concrete wires and resistors.

This insight was more than just a parlor trick. As Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman note in their fantastic 2017 biography, A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age, “circuit design was, for the first time, a science.” As Soni and Goodman elaborate, Shannon had done more than just simplify the job of wire-soldering engineers. He had also introduced a breakthrough idea: that metal and electron circuits could implement arbitrary logic. As Walter Isaacson summarized in The Innovators, “[this became] the basic concept underlying all digital computers.”

Shannon published these leaps in his master’s thesis, which he gave an unassuming title, “A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits.” Nearly seventy years later, as I was writing my own masters thesis at MIT, Shannon’s shadow still loomed large.

I’m recounting this story for two reasons. First, I’m a fan of Shannon, and think he doesn’t get enough credit. His contributions arguably dwarf those of his contemporary, Alan Turing, who Shannon later briefly met when their wartime cryptanalysis efforts overlapped.

Second, and more specifically, I bring him up because a brand new documentary about Shannon, called The Bit Player, was just released on Amazon Prime. It’s directed by Mark Levinson, whose work I admire, and is based in part on the book by Soni and Goodman that I also admire. Needless to say, I’m excited to watch it, and thought many of you might be as well.

July 23, 2020

On Confronting the Productivity Dragon (take 2)

On a recent episode of my podcast, Deep Questions, a listener asked me what to do when one feels overwhelmed with incoming tasks, requests, and ambiguous obligations — a problem that has become unfortunately common in our current period of largely remote and persistently frenzied work.

The temptation in such moments is to curl up as the onslaught engulfs you; perhaps answering the most recent emails to arrive, or tackling a sampling of tasks that seem particularly urgent, but otherwise just hoping the rest will dissipate.

In the mythology of your professional life, in other words, you decline to confront the dragon, and instead put up a half-hearted warning sign, or rage to anyone in earshot about the unfairness of the dragon’s existence in the first place.

My advice was to resist this temptation.

I told the listener to instead confront the dragon. Jot down every loop that opens; whether it comes via email, or a phone call, or a Zoom meeting, or Slack. Because these loops might emerge rapidly, use a minimalist tool with incredibly low friction. I recommended a simple plain text file on your computer in which you can record incoming obligations at the speed of typing (a strategy I elaborate in this vintage post).

Then, at the beginning of each day, before the next onslaught begins, process these tasks into your permanent system. In doing so, as David Allen recommends, clarify them: what exactly is the “next action” this task requires? Stare at this collection before getting started with your work.

It’s quite possible that the list will be terrifying — way more assignments and activities than you can ever hope to accomplish in time. But you should still confront it. Quantify the impossibility of your load. Visualize its contours. Walk into the cave, shield raised, prepared to face what lurks.

I can offer three justifications for this recommendation:

As David Allen argues, obligations that are kept only in your head cause stress and drain mental resources. An overwhelming number of tasks captured in a system that you regularly review will generate a fraction of the angst spawned by trying to instead pretend that those same tasks don’t exist.

Quantifying the impossibility of your assignments makes it much easier to argue for change. When you instead just battle your inbox all day, switching haphazardly between the easy and unavoidably urgent, you can convince yourself that you’re simply busy and need to hustle harder. Enumerating the absurd quantity of these demands will sharpen your conviction that something has to give.

You can optimize. If you have 400 tasks on your list, there’s no way you can accomplish them all in a single day. But if you can see all 400 obligations in one place, then you can choose the five or six that will have the biggest impact. This is almost certainly better than just jumping on whatever caught your attention most recently.

In summary, I told this podcast listener not to confuse the systems with which he organizes his work for the actual quantity of work with which he has been burdened. Abandoning the former won’t reduce the latter, it will only make its metaphorical fiery breath burn all the hotter.

#####

Speaking of productivity, one of my favorite productivity writers, Laura Vanderkam, just published a new ebook original titled, The New Corner Office: How the Most Successful People Work from Home. I couldn’t think of a more relevant book for the frustrated many, like my overwhelmed podcast listener, currently struggling with the “new normal” of the remote workplace.

July 15, 2020

On Deep Work Tents and the Struggle for Focus in an Age of Social Distance

Jessica Murnane is a wellness advocate, writer, and podcaster who interviewed me on her show not long ago. Earlier this year she signed a deal with Penguin Random House to write a new book. This was great news, except for one wrinkle: the coronavirus.

“Writing a book during a pandemic was one of the most challenging things I have ever done,” she told me. Like many working parents during the past few months, she was trying to balance homeschool with the need to accomplish serious, mind-stretching deep work; all without any easy means of finding some peace and quiet.

So Jessica went to an extreme: she setup a beach tent in her backyard, so she could work outside without the sun glaring on her laptop screen (see above). She’s not alone in this innovation: I can think of at least two other people I personally know well who deployed similar tent setups in their yards for similar purposes.

I mention this story to emphasize a point that sometimes gets lost in our technical discussions, both here and on my podcast, about neuro-productivity, workflows, and the deep life: it’s been really, really hard to get things done recently. To the point where we’re setting up tents in our yards.

I strongly believe, however, that it’s still important to push back on these challenges and do our best to structure our obligations, and build our time blocks, and prioritize our deep work to the extent possible. From both a mental health and professional longevity perspective, straining to optimize a hard situation is still better than just giving in to chaos. This commitment might also set you up well to sprint ahead when things eventually, inevitably return to normal, as has happened after every pandemic in the history of humankind.

But we should also all give ourselves a break. This sucks. It will get better. We should keep striving to do our best until then.

In the meantime, if you need me, I’m trying to find an extension cord long enough to plug in the margarita maker I just hauled out to the tent I setup behind my backyard azaleas.

July 7, 2020

Has the Shift Toward Neuro-Productivity Already Begun?

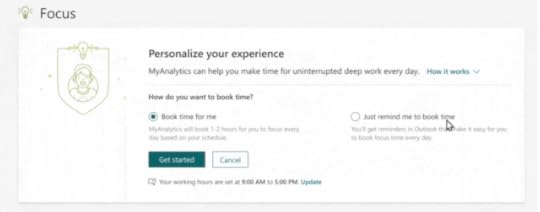

A reader recently pointed me toward an interesting new feature Microsoft added to its widely-used Outlook email and calendar software: support for deep work.

Outlook users can now create a personal “focus plan” that measures how many hours they’re spending dedicated to undistracted work, and can automatically schedule these blocks. Though the tool uses the term “focus time” to label these efforts on your calendar, it also directly uses the term “deep work” in its interface when describing what it’s helping you accomplish (see above).

This is an important shift.

In the first decades of digital knowledge work, human productivity was often viewed through a computer processor metaphor. People were understood as unbounded processors and the goal was to leverage technology to get them as much useful information as possible, with the least amount of friction. In this metaphor, getting more done meant getting more information through the pipeline.

As I’ve been arguing since at least 2016, this is not a useful frame. Humans do not operate on unbounded computer processors, but instead quirky bundles of neurons that have operational properties much different than silicon. If you really want to get more done, you have to understand how human brains actually function, and then arrange for work processes that complement these realities.

Once you start such examinations, one of the most obvious findings is that human brains are not great at context switching. If you want to perform cognitively demanding work, you need to arrange a setting in which your brain can spend time focused on that one task without needing to consider emails, or slack messages, or online news, or Zoom calls, at the same time. An office that segregates deep from shallow work, therefore, should produce more high value output in the same number of total hours.

Given the huge potential productivity gains inherent in a shift toward this neuro-productivity approach, I’ve been convinced that it’s only a matter of time before we began to see large knowledge work players begin to formalize these ideas. Microsoft’s addition of the focus plan feature to Outlook implies that this shift may very well have already begun.

July 2, 2020

A Deliberate Tribute

I was saddened to learn earlier today that Anders Ericsson, creator of deliberate practice theory, recently passed away. Longtime readers of mine know that his work greatly influenced me. I never met Anders in person, but we shared a sporadic correspondence that I cherished. I thought it appropriate to offer a brief personal tribute to his powerful ideas.

Anders tackled the fundamental question of how experts get really good at what they do. The framework he proposed, which clarified a lot of confusion in the field at the time, introduced these two big ideas (among others):

When trying to get better at a skill, an effort called “deliberate practice” is most effective. Deliberate practice, which aims to isolate areas that need improvement and then stretch you past your comfort zone to induce growth, is the critical activity that helps individuals move past amateur status in many endeavors, both physical and cognitive.

To reach an expert level often requires a lot of deliberate practice. In some of Anders’s more engaging studies, he would sift through accounts of so-called “prodigies”, and identify, time and again, prodigious quantities of deliberate practice surreptitiously squeezed into their early childhood years. As his New York Times obituary recalls, Anders once summarized this finding as follows in an interview: “This idea that somebody more or less discovers, suddenly, that they’re extremely good at something, I’ve yet to find even a single example of that type of phenomenon.”

I first came across Anders’s work in Geoff Colvin’s 2008 book, Talent is Overrated, which blew my mind, and led to a deep dive into deliberate practice theory. It provided an antidote to an increasingly frenetic, digital-mediated world, where everyone was trying to find their passion or seek to somehow transmute social media busyness into accomplishment. It explained a lot about what seemed to resonate for me when I reflected on my own life, or surveyed those I admired around me at MIT or in the biographies of big thinkers I was devouring at the time.

The theory laid the foundations in my own writing for the idea that the type of work you’re doing matters (elaborated in Deep Work), and that meaningful accomplishment often requires the diligent application of such efforts over a long period of time (elaborated in So Good They Can’t Ignore You.)

As with many big theories, the implications of Anders’s ideas were sometimes pushed to unsustainable extremes. In Outliers, for example, Malcolm Gladwell deployed these concepts to argue for an over-simplified egalitarian utopia in which all significant achievements are due to incidental environmental factors that enable rapid deliberate practice acquisition. (Anders may have egged Gladwell on, as Anders was known to enjoy advancing extreme versions of his theories; though given the good-natured manner with which he approached subsequent debate, I always suspected that this tendency was in part driven by a Socratic impulse to generate progress through the dialectical clash of opposing conceptions.)

In recent years, deliberate practice theory has continued to evolve. Most contemporary thinking on expert performance includes factors beyond just practice accumulation to understand high achievement, such as trainability, innate physiological advantage, and the complex and murky psychological cocktail we often summarize as “drive.”

There’s also an increased consideration of the type of skill being mastered. If there are clear cut rules and feedback, like when learning chess or golf, the application and advantages of deliberate practice are clear. In other pursuits, however, such as the ambiguous, semi-creative, semi-administrative efforts that define knowledge work, designing appropriate practice can be maddeningly difficult and its rewards less immediately obvious. (Though, as I argue in So Good, this is a challenge worth undertaking, as its difficulty scares most people off, leaving a huge competitive advantage for the few willing to apply a deliberate approach to their office-bound skills.)

In the end, however, Anders’s key ideas — that the type and quantity of practice matters a lot — remain widely accepted. He transformed our understanding of the world from a frustratingly unobtainable vision in which people stumbled into their prodigious talent and lived happily ever after, into a more democratized and tractable reality; one in which your abilities are mutable, and disciplined diligence — though perhaps unable to transform you into the next Tiger Woods — will almost always push your skills to a place where they can do you some real good.

Anders will be missed. His ideas will not be forgotten.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9946 followers