Cal Newport's Blog, page 20

April 17, 2020

Beyond To-Do Lists

I was talking recently with a friend who is a project manager at a tech company who happens to also be particularly interested in productivity strategies. He told me about a fascinating habit he’s been deploying with great success in his own work life. Instead of maintaining endless to-do lists, when he takes on a new obligation, he puts it on his calendar: scheduling a specific date and time when he will tackle it. As he clarified, this approach applies even if the obligation is just to “think some about this topic.”

This might sound extreme, but it shouldn’t. What my friend is really doing is acknowledging that he has a limited amount of total time to spend on tasks. By scheduling each obligation, he’s confronting the reality of how much time each item will actually take, and identifying where these mental cycles will come from.

In knowledge work, we often ignore these realities. We pass around obligations like hot potatoes, via dashed-off emails and Slack eruptions, often pushing ourselves beyond what we can realistically accomplish, compensating by dropping things or completing them at a low quality level. This can’t possibly be the best way to organize cognitive work. And as my friend demonstrates, it’s not the only way.

I’ve been writing all week about how the disruptions in knowledge work we’re facing in the current moment might be an opportunity to spark radical new ideas about how this sector operates. This particular issue, confronting how we’re actually allocating our attention, is as good a place as any to start.

April 15, 2020

The Dichotomy of Email

I want to add a quick addendum to my recent series of posts about avoiding email overwhelm in our current moment of total remote work. Though longtime readers have heard me talk about this before, it’s important to emphasize the dichotomous nature of this tool:

On the one hand , email is a massively useful way to send text and files to individuals or groups. It’s much better than voicemails or memos. If we had to go back to these older technologies it would be a major pain.

On the other hand , email makes us miserable.

How are both true at the same time? The problems with email are less about the tool than they are about how we deploy it. We run more and more of our work through a single undifferentiated inbox, which means we constantly feel overloaded, and end up context-shifting frenetically between dozens of concurrent but unrelated asynchronous conversations (which, as I argue in Deep Work, is a cognitive disaster).

I mention this only to help diminish any nagging cognitive dissonance. It’s perfectly consistent to love the convenience of shooting off a digital file to your team in an efficient message, while at the same time dreading what awaits you in your inbox.

(Photo by Phil Roeder.)

April 14, 2020

Beyond the Inbox: Rules for Reducing Email

In my last post, I warned that a sudden shift to remote work could inadvertently push knowledge workers into a state of inbox capture, in which essentially all of their time outside of Zoom calls ends up dedicated to sending and receiving email (or Slack messages). As I hinted, I think the best solutions here require radical changes to how these organizations operate. In the short term, however, I thought it might be useful to provide a few ideas about what individuals can do right away to avoid the perils of this state of capture.

It’s important to first bust a popular belief. The key to spending less time in your inbox is not simply to check it less often. This advice is out of date, echoing a simpler time when emails were novel. In recent years, of course, this technology has (unfortunately) become the medium in which most work now unfolds. Ignoring your inbox for long stretches with no other accommodations might seriously impair your organization’s operation.

What’s instead imperative is to move more of this work out of your inbox and into other systems that better support efficient execution. You can’t, in other words, avoid this work, but you can find better alternatives to simply passing messages back and forth in an ad hoc manner throughout the day.

Here are three concrete rules along these lines to help clarify what I mean…

Rule #1: Never schedule a call or meeting using email.

In our current moment in which casual conversations in the hallway or impromptu office visits are impossible, you have to be using meeting scheduling services that allow people to select a time from your list of available times. Use calend.ly, use Acuity, use the features built into Microsoft Outlook, and if you’re setting up a group meeting, use Doodle. But do not let this coordination unfold as a slow back-and-forth exchange of messages, as this is guaranteed to keep you in a state of constant, agitated inbox checking.

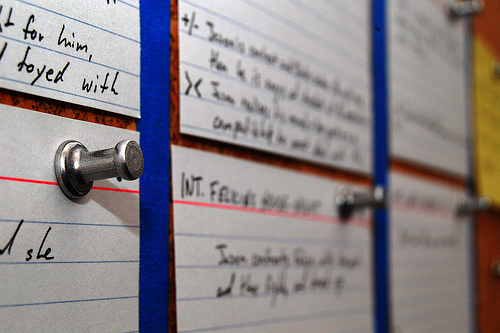

Rule #2: Immediately move obligations out of your inbox and into role-specific repositories.

I currently inhabit four professional roles: writer, teacher, researcher, and director of graduate studies for my department. For each of these roles, I set up a Trello board that includes a column for: things I’m working on actively, thing I’m waiting to hear back about from someone else, things on my “back burner” that I’m not yet ready to tackle, and a list of ambiguous or complicated things that I need to spend some time on figuring out. Every email I receive immediately gets moved to one of these columns in one of my Trello boards.

This might seem arbitrary, but it’s actually critical to keeping me away from endless inbox wrangling. It means, among other benefits, that I can focus on one role at a time. For example, when I’m spending time on my role as director of graduate studies, I’m only exposed to information about this role — preventing energy-sapping context shifts. I can see the whole picture of what’s on my plate, and make smart decisions about what I want to work on in the moment.

Seeing the status of my obligations in one place also significantly simplifies the process of consolidating multiple tasks and identifying systems that might make work more efficient in the future (I’m in the process, for example, of launching an FAQ page on our departmental web site that instructs our graduate students how to execute many common activities without needing to send me ambiguous emails).

This approach is an order of magnitude more efficient than instead collapsing all of these obligations into a haphazard jumble piled up in a single undifferentiated inbox.

Rule #3: Hold office hours.

Setup a recurring Zoom meeting for set times every week where you guarantee to be present. As much as possible, when people send you an ambiguous request or initiate a conversation that will require a lot of back and forth, point them toward your office hours schedule and tell them to stop by next time they can to discuss. It’s a simple idea, but it can reduce the number of attention-snagging back-and-forth electronic messages in your professional life by an order of magnitude.

Us professors, of course, have long used this strategy to moderate student interaction into more sustainable patterns that work better for all parties involved. In our current period of widespread remote work, however, this should be much more common. (I actually proposed this idea in a 2016 article I wrote for the Harvard Business Review; it’s also promoted in Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson’s 2018 book, It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work).

April 12, 2020

Task Inflation and Inbox Capture: On Unexpected Side Effects of Enforced Telework

I’ve spent years studying how knowledge work operates. One thing I’ve noticed about this sector is that it tends to treat the assignment of work tasks with great informality. New obligations arise haphazardly, perhaps in the form of a hastily-composed email or impromptu request during a meeting. If you ask a manager to estimate the current load on each of their team members, they’d likely struggle. If you ask the average knowledge worker to enumerate every obligation currently on their own plate, they’d also likely struggle — the things they need to do exist as a loose assemblage of meeting invites and unread emails.

What prevents this system from spiraling out of control is often a series of implicit friction sources centered on physical co-location in an office. For example:

If I see you in the office acting out the role of someone who is busy, or flustered, or overwhelmed, I’m less likely to put more demands on you.

If I encounter you face-to-face on a regular basis, then the social capital at stake when I later ask you to do something via email is amplified.

Conference room meetings — though rightly vilified when they become incessant — also provide opportunities for highly efficient in-person encounters in which otherwise ambiguous decisions or tasks can be hashed out on the spot.

When you suddenly take a workplace, and with little warning, make it entirely remote: you lose these friction sources. This could lead to extreme results.

In some roles, for example, in the absence of this friction task inflation might become endemic, leading knowledge workers to unexpectedly put in more hours even though they no longer have to commute and are freed from time-consuming business travel obligations.

This inflation might even collapse into a dismal state I call inbox capture, in which essentially every moment of your workday becomes dedicated to keeping up with email, Slack, and Zoom meetings, with very little work beyond the most logistical and superficial actually accomplished — an incredibly wasteful form of economic activity.

What’s the solution to this particular issue? Knowledge work organizations might have to finally get more formal about how tasks are identified, assigned, and tracked. This will require inconvenient new rules and systems, but will also, in the long run, probably be a much smarter way to work, even when we can return to our offices.

More generally, I think this is just one example among many where the sudden disruption that defines our current moment will force us to confront aspects of knowledge work that up until now have been barely functional, and ask: what’s the right way to get this work done?

(Photo by Corley May.)

April 10, 2020

Nick Saban Just Got Email

By most measures, Nick Saban is one of the most successful college football coaches in the history of the sport. As revealed in a recent interview with ESPN, however, he’s not exactly tech savvy. During this discussion, Sabin revealed that up until the last few weeks, when unavoidable remote work forced some changes, he had never used email.

I think this is an important story. Not because Saban’s specific work habits can be widely replicated (Saban, who was paid $8.6 million last year, has a staff who handles incoming requests), but because it underscores a point that we often forget. Low friction communication makes a lot of modern work easier, because it allows you to avoid the pain of setting up and optimizing systems that organize your efforts. But easy is not the same as effective.

We’re in a moment right now in which a lot of knowledge workers, dislodged from their normal routines, are forced to look at their work from a fresh perspective. There’s an opportunity lurking here among the abundant negatives: we might notice that our current commitment to unrelenting, uncontrolled, attention-devouring incoming communication is not necessarily the sine qua non of digital age productivity.

Saban didn’t need to check an inbox every five minutes to win six championship titles. This might be less exceptional than we realize.

(Image by Photographer 192)

April 9, 2020

More Thoughts on Amplifying Meaning in Your Work

Earlier this week I explored how practitioners of the deep life sometimes use inspiring environments to amplify the meaning they derive from their work. Today, I want to briefly elaborate on two other strategies I’ve observed for accomplishing this same goal…

The first is establishing cultures of meaning. This is common, for example, in many military communities which emphasize a shared narrative about the honor and noble sacrifice of martial endeavors. If you want to see a contemporary example of this strategy in action listen to basically any episode of former Navy SEAL Jocko Willink’s podcast. He doesn’t dispense advice or opine about the state of the world; he instead mainly interviews war heroes to discuss the gritty reality of their experience. I’ve noticed similar cultures of meanings among teachers, fine craftsmen, and, relevant to recent events, medical professionals, who time after time demonstrate they are willing to keep returning to dangerous and unbelievably trying circumstances. That’s a powerful culture.

The second strategy I’ve noticed for amplifying meaning is to cultivate communities of common purpose. The veteran officers of the Continental Army formed The Society of the Cincinnati to maintain their connection to the revolutionary spirit. Within my circle of youngish non-fiction writers, there’s a semi-regular gathering that takes place at a rented cabin to talk shop and trade advice (though, regrettably, I’ve not yet been able to attend). As I’ve written about before, long tail social media has enabled numerous niche groups to leverage the internet to maintain virtual bonds among those with shared vocational interests. The ability to regularly gather with others who are developing and deploying the same craft helps ground these efforts on a more solid foundation of meaning.

This list of strategies is not comprehensive, but it underscores the general point. The deep life contains an emphasis on craft. Just developing and leveraging your rare and valuable skills, however, is not enough. To maximize the sense of fulfillment they generate requires a continuous and concerted effort toward activities designed to amplify meaning.

(Photo by Jelle.)

April 6, 2020

Amplifying Meaning with Environment

In my recent post about work and the deep life, I mentioned that some practitioners of this philosophy seek ways to amplify the meaning they derive from their craft. There are many strategies to accomplish this goal. One that’s always intrigued me is the use of radical environments to induce more inspiration and extract more satisfaction from one’s work.

For example, Adam Savage’s cave:

Or Laird Hamilton’s house in Hawaii:

Or Killiechassie, J.K. Rowling’s Scottish country estate (on the grounds of which she supposedly built a replica of Hagrid’s Hut).

These are grand examples, but there’s a tractable principle lurking. A craft can be more than a way to make a living; if properly cultivated, it can also become central to your sense of meaning.

####

A couple logistical notes for those seeking high quality distraction:

My friend Scott Young just re-opened his popular course Rapid Learner. Seems like a smart time to brush up on your ability to learn hard things fast.

Last month I read a fascinating article in Smithsonian Magazine (yes, I subscribe) by a biomedical engineer named Rachel Lance about her quest to understand the final moments of the ill-fated confederate submarine, the HL Hunley. I was excited to find out she has a new book about this work titled In The Waves. I just ordered it. If you love these scientific-historical detective stories as much as I do, consider doing the same.

April 5, 2020

Work and the Deep Life

One of the key elements of my deep life philosophy is its emphasis on craft. This topic applies to both professional and leisure pursuits, but in this post, I want to focus on the former. (See Digital Minimalism for more on the latter.)

I became really interested in career development ideas around 2010, when I began the research for what eventually became my fourth book, So Good They Can’t Ignore You. Here’s what I discovered about the standard career thinking embraced by many college-educated young people in our country:

It understands jobs to be like a contract: you do the work assigned, you get to keep the position.

It believes career satisfaction results from finding the right job for your natural pre-existing interests. This mindset is summed up by the ubiquitous advice to “follow your passion.” If you don’t like your job, it’s because you chose the wrong field.

The deep life philosophy offers an alternative vision centered on valuable skills:

It believes security comes from being able to do things that are valuable, and, more generally, being comfortable picking up new valuable skills quickly when circumstances require.

It believes that satisfaction comes from some combination of autonomy, impact and/or a sense of mastery, which (as I argue in So Good) require valuable skills as a necessary precondition.

If you subscribe to standard career thinking, you focus on work ethic; implicitly believing that if you tell people enough times that you’re “busy” when they ask how you’re doing that this will somehow alchemize into indispensability. In times of plenty, you also expend a lot of energy pondering whether your current work is really your “passion,” and daydream about job shifts that might unlock a torrent of latent satisfaction. (Such thinking, naturally, is suppressed during times of economic strain.)

If you subscribe to deep career thinking, by contrast, you focus intensely on training high-value skills, like an athlete looking to maintain an edge. Skills not only provide you security (effort, relatively speaking, is abundant, while there’s always a demand for value-producing expertise), but they can be used as leverage to gain more autonomy, or increase your sense of impact, or provide that powerful feeling of fulfillment found only in mastery: all of which will make your work more satisfying.

Those who lead a deep life, however, also tend to seek ways to boost the meaning they derive from their work. Both dedicated teachers and career military professionals, for example, are known to cultivate well-justified structures of deep meaning around their craft. (I admire both these groups immensely.) While those engaged in purely intellectual pursuits, like professors and writers, often seek inspiring physical environments in which to work.

This is the deep approach to work: Master a useful craft, use this mastery to shape your working life in a way that’s both secure and satisfying, then look to build structures around your efforts that further amplify their meaning.

I only wish this was as easy to do as it was to explain…

April 3, 2020

Thoreau on Hard Work

Writing in his journal in March of 1842, at the precocious age of 24, Thoreau noted the following about the difference between quality and quantity in work:

“The really efficient laborer will be found not to crowd his day with work, but will saunter to his task surrounded by a wide halo of ease and leisure. There will be a wide margin for relaxation to his day. He is only earnest to secure the kernels of time, and does not exaggerate the value of the husk. Why should the hen set all day? She can lay but one egg, and besides she will not have picked up materials for a new one. Those who work much do not work hard.”

At the age of 27, having just finished writing a book concurrently with my doctoral dissertation, I was afflicted with a similar revelation, which I captured in a blog post published in the summer of 2009, titled: “Focus Hard. In Reasonable Bursts. One Day at a Time.” The main distinction I emphasized in this piece (admittedly, with much less eloquence than Thoreau) is that there’s a difference between “hard work” and “hard to do work.” Deep endeavors are often difficult, but they need not be exhausting.

#####

For the past three weeks, I’ve switched over to a daily blog schedule. My idea, as explained here, is to be the one source of information in your life that is not specifically about public health concerns (if you want more on my take on that particular topic, see this post or my recent interview with GQ). Now that people are settling down into a regular rhythm of socially-distant living, I’m thinking of adjusting my post frequency for now to be roughly every other day, so that you’ll still hear from me regularly, but not so fast that you’re unable to keep up!

April 2, 2020

On Productivity, Part 3

In March of 2009, only a couple years into the life of this blog, I wrote a post that attempted to summarize what I was up to. I titled it: “What the Hell is Study Hacks?” At the time, I was focused exclusively on advice for students. I had published two books for this audience with Random House and had a third about to come out. But as I reread this post recently, I was surprised by the degree to which my circa-2009 ideas for students seemed to resonate with our current conversations. Here’s what I wrote:

My philosophy for achieving this goal can be reduced to three simple rules:

Do fewer things.

Do them better.

Know why you’re doing them.

All of the important advice on this site circles back to these same three themes.

I meant it. For a while during this period, the tagline of this blog, listed right under the title at the top of the site, was: “Do less, do better, know why.”

A decade ago, I was directing this advice toward stressed out undergrads, who were lost and miserable, burnt out on overloaded schedules and fueled by a diminishing momentum whose original source they couldn’t really remember anymore. But there’s a more general truth lurking beneath this thinking. Many problems in our current culture come from this same place. We do too much, most of it not very well, and are not even sure why we’re bothering.

When you reverse this formula, you give yourself the chance to end up somewhere deep.

(Photo by Giuseppe Milo)

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9947 followers