Cal Newport's Blog, page 23

March 10, 2020

More Evidence of Facebook’s Negative Impact

Last week, I wrote about a paper appearing in the American Economic Review that conducted a randomized trial to measure the personal impact of deactivating Facebook. A few days later, a different study was published, this one appearing in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, that also deployed a randomized trial to measure the impact of reduced Facebook use.

The authors of this new paper, a group of psychologists from Ruhr-Universität Bochum, in Germany, randomly split a group of roughly three hundred volunteers into an experiment and control group. The participants in the experiment group were asked to reduce their daily Facebook use, while the control group made no changes.

Personal impacts were measured with online surveys administered at regular intervals. To summarize the paper’s main findings:

“Life satisfaction significantly increased, and depressive symptoms significantly decreased. Moreover, frequency of physical activity such as jogging or cycling significantly increased, and number of daily smoked cigarettes decreased. Effects remained stable during follow-up (three months). Thus, less time spent on Facebook leads to more well-being and a healthier lifestyle.”

Based on what I observed researching Digital Minimalism, a key dynamic at play in these numbers is likely the shift from Facebook to more rewarding activities. This is what participants in my own study kept reporting: it’s not that the time they spent on social media was always negative on its own, the problem was instead the time social media took away from other activities that are more positive.

A deep life, in other words, tends to minimize the hours spent staring mindlessly at screens, but it does so not because the screens are bad, but because there’s too much else good going on to spare the attention.

February 29, 2020

Top Economists Study What Happens When You Stop Using Facebook

In the most recent issue of the prestigious American Economic Review, a group of well-known economists published a paper titled “The Welfare Effects of Social Media.” It presents the results of one of the largest randomized trials ever conducted to directly measure the personal impact of deactivating Facebook.

The experimental design is straightforward. Using Facebook ads, the researchers recruited 2,743 users who were willing to leave Facebook for one month in exchange for a cash reward. They then randomly divided these users into a Treatment group, that followed through with the deactivation, and a Control group, that was asked to keep using the platform.

The researchers deployed surveys, emails, text messages, and monitoring software to measure both the subjective well-being and behavior of both groups, both during and after the experiment.

Here are some highlights of what they found:

“Deactivating Facebook freed up 60 minutes per day for the average person in our Treatment group.” Much of this time was reinvested in offline activities, including, notably, socializing with friends and family. “Deactivation caused small but significant improvements in well-being, and in particular in self-reported happiness, life satisfaction, depression, and anxiety.” The researchers report this effect to be around 25-40% of the effect typically attributed to participating in therapy. “As the experiment ended, participants reported planning to use Facebook much less in the future.” Five percent of the Treatment group went even farther and declined to reactivate their account after the experiment ended. “The Treatment group was less likely to say they follow news about politics or the President, and less able to correctly answer factual questions about recent news events.” This was not surprising given that this group spent 15% less time reading any type of online news during the experiment.“Deactivation significantly reduced polarization of views on policy issues and a measure of exposure to polarizing news.” On the other hand, it didn’t significantly reduce negative feelings about the other political party.

This study validates many of the ideas from Digital Minimalism (indeed, the paper even cites the book in its introduction). People spend more time on social media than they realize, and stepping away frees up time for more rewarding offline activities, leading, in turn, to an increase in self-reported happiness and a decrease in self-reported anxiety.

The main negative impact experienced by the Treatment group was that they were less up to date on the news. Some might argue that this isn’t really negative, but even for those who prioritize current events knowledge, there are, obviously, many better ways to keep up with news than Facebook.

Perhaps most interesting was the disconnect between the subjects’ experience with deactivating Facebook and their prediction about how other people would react. “About 80 percent of the Treatment group agreed that deactivation was good for them,” reports the researchers. But this same group was likely to believe that others wouldn’t experience similar positive effects, as they would likely “miss out” more. The specter of FOMO, in other words, is hard to shake, even after you’ve learned through direct experience that in your own case this “fear” was largely hype.

This final result tells me that perhaps an early important step in freeing our culture from indentured servitude in social media’s attention mines is convincing people that abstention is an option in the first place.

February 26, 2020

Alfred North Whitehead’s Awe-Inspiring Focus

Alfred North Whitehead was an early 20th-century mathematician and philosopher. He’s known, among many contributions, for his magisterial three-volume treatise, Principia Mathematica, which was written with Bertrand Russell and attempted to reduce all of mathematics to implications of a master set of logical axioms (Kurt Gödel, of course, had other ideas about this particular endeavor).

Whitehead later turned his attention from mathematics toward the philosophy of science, and then on to metaphysics. In total, he published 23 books between 1898 and 1948.

What does it take to produce cognitive output at such a high level? Bertrand Russell gives us a hint in the following scene from his autobiography:

“[Whitehead’s] capacity for concentration on work was quite extraordinary. One hot summer’s day, when I was staying with him at Grantchester, our friend Crompton Davies arrived and I took him into the garden to say how-do-you-do to his host. Whitehead was sitting writing mathematics. Davies and I stood in front of him at a distance of no more than a yard and watched him covering page after page with symbols. He never saw us, and after a time we went away with a feeling of awe.”

One of the things that worries me about the shoulder-shrugging manner in which our current culture is diminishing uninterrupted thinking is that I can’t help but wonder how many potential modern Whiteheads, growing up in a world of fragmentation and connectivity-primacy, will never make it to writing their own masterpieces.

February 16, 2020

Sir William Osler’s Advice to Students: Practice Concentrating on Hard Things

Sir William Osler is one of the most important figures in the founding of modern medicine. In 1910, he published a book titled Aequanimitas: With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. It builds on a farewell address he gave at the Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1889, and details his thoughts on what it takes to thrive in an intellectually demanding medical field.

As one of my readers helpfully pointed out recently, chapter 18 of this book contains the following prescriptive gem about how to succeed in an endeavor that requires you to create value with your mind:

“Let each hour of the day have its allowed duty, and cultivate that power of concentration which grows with its exercise, so that the attention neither flags nor wavers, but settles with bull-dog tenacity on the subject before you. Constant repetition makes a good habit fit easily in your mind, and by the end of the session you may have gained that most precious of all knowledge—the power of work.”

What struck me about this quote, in addition to it being a nice endorsement of the deep life, is that it comes from an educator. To Olser, it was clear that training a new generation of thinkers required teaching students how to actually put their mind to productive use, which is hard, and requires “bull-dog tenacity” before it becomes a “good habit.”

We don’t teach this any more.

Modern educational institutions care a lot about content: what theories we teach, what ideas students are exposed to, what skills they come away knowing. But we rarely address the more general question of how one transforms their mind into a tool well-honed for elite-level cognitive work.

We have, in other words, largely given up talking explicitly about this element of the intellectual life. This might be in part because it seems too pragmatic and not sufficiently lofty. I suspect it’s also due in part to the fact that educators themselves, drowning in a sea of email and unchecked administrative obligations, don’t feel comfortable pushing a lifestyle they don’t themselves lead any more.

But regardless of the reason, this omission is almost certainly made to our culture’s detriment. I suspect (though can’t yet prove), that an educational institution that unapologetically made deep work a core principle, would not scare off a generation used to staring at screens, but instead find itself deluged with applicants hungry to taste a more meaningful mode of existence.

February 9, 2020

On Thomas Edison, Technophobia, and Social Media Criticism

I recently finished Edmund Morris’s epic new Thomas Edison biography. It took me a while to get used to his reverse chronology structure (he works backwards from Edison’s later years to his earlier years), but once I did, I found it riveting.

One thing that caught my attention from the book was the degree to which early 20th century Americans were exposed to rapid technological change. We think the arrival of the internet and smartphones were a big deal, but these innovations were trivial in magnitude compared to the arrival of electricity.

Constraints that had been constant throughout all of human history — the darkness of night, the slow pace of information dissemination — were obliterated in just a few decades.

Edison was born in an age of horses and sailing ships. He death was broadcast worldwide via radio waves, and whole cities — their streets clogged with cars and their skies blotted with steel-girded buildings — temporarily powered down their ubiquitous electric lights to honor his passing.

These changes naturally led to some reactionary technophobia (though, as I argued in a recent op-ed for WIRED, there wasn’t as much of this resistance as popular commentators like to imply). I’m interested in this historical moment of technophobia, as skeptical technology commentators such as myself, or Tristan Harris, Jaron Lanier, and Douglas Rushkoff, are sometimes associated with this tradition by our detractors.

But does this analogy hold up?

There are two problems with connecting the types of ideas discussed in books like Digital Minimalism to Edison-era technophobia.

The first is that many of the anti-technology voices from the early 20th century were disturbed in large part because they didn’t understand the new technology (a new phenomenon in a world in which tools had always before been physical and intuitive). Electricity seemed wholly mysterious and borderline occult.

Modern technology skeptics, however, tend to instead be technologists who are thoroughly familiar with new innovations. I trained in MIT’s Theory of Distributed Systems and Network and Mobile Systems groups: it’s hard to tag me as baffled by the operation of a modern social network or broadband wireless internet.

The second problem is the Edison-era technophobes tended to reject the entire program of new electrical technology as bad. The whole movement scared them, and they wanted nothing to do with it.

Modern skeptics such as myself, Lanier, and Rushkoff, by contrast, have been internet-boosters since its earliest days, and still hold semi-utopian visions about how internet technologies can improve the world. It’s hard to tag us as scared of change in a field where we’ve consistently supported positive disruption.

A better analogy from the time of Edison is his own battle against George Westinghouse to determine whether alternating current was superior to direct current for municipal energy generation. No one at the time thought Edison was anti-electricity or scared of change. They instead recognized he was debating what direction was best for this particular technology’s advancement.

This is the generous interpretation I give to my own critiques of social media. I love the internet, but worry that trying to consolidate it under the control of a small number of Orwellian conglomerates is a costly detour, impeding instead of promoting its advancement. Lanier, Rushkoff, Harris would almost certainly say something similar.

This doesn’t mean we’re right (Edison was wrong in his preference for direct current), but it also doesn’t mean that we were somehow duped by an ill-informed moral panic.

To summarize my take away from studying the life and times of Thomas Edison, be wary of confusing technophobia and techno criticism. The former is not as common as we like to think, and the latter has always been absolutely crucial — especially when delivered by fellow technologists — in the quest to unlock more and more human potential.

Now if I could only figure out how invent the 21st century equivalent of the light bulb…

February 7, 2020

Edward’s Analog January

It’s been about a month since I proposed the Analog January Challenge. Accordingly, I’ve begun to receive reports from those who’ve made it through a full four weeks of enhanced analog activity.

I thought it would be interesting to share one of these case studies…

One of the first reports I received was from Edward (not his real name), a young man living in London, who ended up traveling to Florida to visit family during the month.

Edward claimed that jet lag complicated the READ piece of the challenge, but he still managed to finish two biographies, a non-fiction book on psychology, and Gone With the Wind. He also started Little Women, as he figured it was probably smart to have read the book before going to see the Greta Gerwig film.

As for the MOVE piece, Edward noted that “London really does save my butt on this one.” While in the city, he found it both easy and enjoyable to walk its historic streets, observing his surroundings and allowing his own thoughts to keep him company. When the “crazy city noise” got overwhelming, he’d find refuge in Hyde Park.

Edward’s time in Florida, on the other hand, was a different story. As he explained, unless you live in one of the Sunshine State’s big cities, “the incentive to move for any reason is severely curtailed.”

As an extrovert living in a city for most of the month, the CONNECT piece of the challenge was easy. He told me he had no trouble finding twenty people with which to hold conversations. He even ended up in a deep conversation with the flight attendants on his flight to the states.

As for MAKE, Edward took on an unusual, but frankly awesome challenge: memorizing London’s famously complicated street layout. “When I have a free afternoon,” he explained, “I do this by riding a bus route for its entire length.” He adds the obvious coda: “it’s a great exercise in mental solitude — nothing to think about but the road ahead.”

Reflecting on the MAKE challenge, Edward noted that part of the difficulty of pursuing any skilled hobby is that it will likely require some sort of regular practice routine, which is not always an easy addition to an already busy schedule.

On the other hand, he found deeper value lurking in his struggles to decipher London’s streets: it sharpened his appreciation for how hard it is to actually do things that are worthwhile.

“I’m seeing people who are having a bad time managing their expectations about their world,” he mused. “There’s a confusion about how much effort someone needs to put into something in order to find success.” A few afternoons lost among London’s labyrinthian road system cured this hubris.

Finally, there was the JOIN piece of the challenge. “HUGE progress,” Edward summarized. He had been worried about this part of Analog January as he couldn’t think of anything that he might want to actually participate in on a regular basis.

Then a friend of his asked him to join a weekly Dungeons and Dragons group. “This really isn’t my cup of tea,” Edward explained, but because he was participating in the challenge, he figured he would give it a shot.

He now find himself every Sunday, from 1 to 5, sitting with a group of friends in an office boardroom, rolling the dice and slaying orcs. “I still don’t quite understand the game,” Edward admits, and it’s occasionally a touch boring, but it provides four hours every week when he knows he’ll be sitting in a room with real people, in no particular rush, just being present, and talking, and passing snacks and trying to figure out those damn weird dice.

“It’s now easily the most fixed routine I have,” he said.

What strikes me about Edward’s story are not the specific ways with which he filled his time during his Analog January Challenge — as these are unique to his particular situation — but instead the sheer volume and variety of non-screen related activities in his life during this month.

So many have allowed the contours of their existence outside of work, family obligations and school to shrink down to the comforting numbness of a screen, that it can be bracing at first to encounter the intense engagement of a life that’s lived free from passive consumption, and instead rich in so much that’s so real.

(Photo by Rodrigo Galindez)

January 26, 2020

The Platform Exceptionalism of YouTube

The major social media services are often described as fundamental platforms of the internet age. The companies that control these services use this argument to justify their astronomical valuations, and their critics use it to validate the need for regulatory intervention.

As longtime readers know, I’m often skeptical of this digital deification.

Services like Facebook, Twitter or Instagram aren’t really platforms: instead of providing core functionalities on which others can build a diversity of useful applications (the standard definition of a platform), they instead offer closed ecosystems in which they carefully monitor and control user behavior.

These services are also far from fundamental. Nothing about web teleology, for example, implies that Twitter’s arcane mix of short-message formats, ampersands, and retweet ratios is an unavoidable technological advance. If Jack Dorsey shut down his Frankenstein’s monster tomorrow, few would wake up a year from now really missing what it added to the online universe.

Recently, however, I’ve been grappling with the idea that there’s one immensely powerful social service about which my skepticism doesn’t seem to neatly apply. I’m talking about YouTube.

To start with, unlike tweets or tagged photo sharing, streaming video is fundamental. The original HTML- dominated version of the web democratized and decentralized the publication of the written word. Online streaming video is doing the same for the moving picture, an equally, if not more important form of media for many people.

Furthermore, YouTube, unlike its peers in the pantheon of social media giants, really can act like a platform. Though it still offers a purposefully addictive and creepily-surveilled user experience at YouTube.com (few rabbit holes run deeper than those excavated by their algorithmically-enhanced autoplay suggestions), the service also allows its videos to be embedded in third-party websites, enabling it to behave like an actual platform that can support a wide array of non-affiliated communities.

I was thinking about this the other day when visiting Tested.com, a technology-oriented web site, primarily built around original videos hosted on YouTube.

A site like Tested could never exist if they had to develop their own reliable, international, low-latency, multi-platform delivery network. But with YouTube providing these core services, the site’s founders could instead focus on innovating content.

And with the advent of low-cost HD cameras and tunable LED light boards, the content on sites like Tested is starting to get pretty damn good, rapidly approaching the quality and user engagement of an old-fashioned cable channel, but at a fraction of the price. I’m equally happy watching the always fantastic Adam Savage in a One Day Build video on Tested.com as I am watching an episode of his current Discovery Channel show, Savage Builds, and yet the former cost thousands of dollars to produce while the latter required many millions.

(There’s still a lot of innovation required before these independent video sites reach their full potential — replacing a blog-style timeline format with a Netflix-style interface , for example, might go a long way to encouraging more engagement — but the potential is clearly there.)

YouTube, of course, would probably prefer that this long tail challenge to television would occur entirely within their own chaotic, and often wildly uneven web site, but this isn’t crucial to their survival: they can still play ads on videos embedded elsewhere and split the revenue.

I don’t mean to be an apologist for YouTube, as there’s a lot I don’t like about how their core web site operates, which somehow both numbs your mind while pushing your buttons, and has a way of leaving you feeling vaguely uneasy after too much time spent browsing offerings that bounce chaotically from solid to sordid.

But nonetheless, something interesting is happening with its platform functions. Whereas Facebook, Instagram and Twitter built their fortunes trying to tame the decentralized energy of the original web, forcing users into their walled company towns where behavior is tightly controlled, YouTube might just end up eclipsing them all in importance by enabling the opposite; boosting instead of dampening the ability of the individual to try their hand at building something original.

December 31, 2019

The Analog January Challenge

One of the surprising lessons I learned working on Digital Minimalism is that when it comes to reforming your relationship with your devices, successful outcomes are less about deciding to stop harmful digital behaviors than they are about deciding to start committing to meaningful analog alternatives.

If you simply resolve to quit social media, and end up sitting on your coach, bored, white knuckling the urge to check Twitter, you’re unlikely to experience lasting change.

On the other hand, if you fill your life with hard but satisfying analog alternatives — activities that resonate with our primal urges to connect, to move, to reflect, to be surrounded by nature, to manipulate elements of the physical world with out hands — you’ll find the appeal of animated GIFs and ASCII snark to be greatly diminished.

With this in mind, I’m introducing the Analog January Challenge. It’s a collection of five commitments that last one month. They’re designed to provide you a crash course introduction to the types of satisfying analog activities that will reduce the anxious attraction of your screens.

(Note: you don’t have to begin exactly on January 1st; just block off four weeks starting on whatever day in the month you initiate the challenge.)

Here are the five commitments that make up the Analog January Challenge:

READ

Commit to reading 3 – 4 new books during the month. It doesn’t matter if they’re fiction or non-fiction, sophisticated or fun. The goal is to rediscover what it feels like to make engagement with the written word an important part of your daily experience.MOVE

Commit to going for a walk every single day of the month. Try to make it at least 15 minutes long. Leave your phone at home: just observe the world around you and think.CONNECT

Hold a real conversation with 20 different people during the monthlong challenge. These conversations can be in person or over the phone/Facetime/Skype, but text-based communication doesn’t count (you must be able to hear the other person’s voice). To hit the 20 person mark will require some advance planning: you might consider calling old friends or taking various colleagues along for lunch and coffee breaks.MAKE

Participate in a skilled hobby that requires you to interact with the physical world. This could be craft-based, like knitting, drawing, wood working, or, as I’ve taken to doing with my boys, building custom circuits. This could also be athletic, like biking, bow hunting, or, as is increasingly popular these days, Brazilian Ju Jitsu. Screen-based activities don’t count. To get the full analog benefit here, you need to encounter and overcome the resistances of the physical landscape that surrounds you, as this is what our minds have evolved to understand as productive action.JOIN

Join something local that meets weekly. For many people, this might be the hardest commitment, but it’s arguably one of the most important, especially as we enter a political season where the pseudo-anonymity and limbic-triggers of the online world attempt to bring out the worse in us. There’s nothing more fundamentally human than gathering with a group of real people in real life to work on something real together. This has a way of lessening — even if just briefly — the sense of anxious despair that emanates from the online upside down.

You might be wondering how you’re going to fit these commitments into your already busy life. The answer is simple: by spending less time online. This was another one of interesting discoveries I made working on my book: people were often surprised by how much free time they had once they stopped treating their phone as a constant companion.

To take advantage of this reality, I recommend that for the duration of the challenge that you dumb down your smartphone by following the rules I outlined here (summary: use your phone only for calls, texts, maps, and audio — as Steve Jobs originally intended).

Furthermore, I’d suggest that when you access social media on your computer, you always log out when you’re done, and un-save your password — introducing the crucial extra friction of typing in this information every time you want to check your account.

Finally, if you have a YouTube habit, you might consider temporarily deploying an internet blocking tool (like Freedom) to strictly limit the times during which you’re allowed to wander down streaming video rabbit holes.

If you’re unhappy with the out-sized role your phone plays in your daily life, I highly recommend trying this challenge, as it builds upon a powerful but often overlooked truth: We fall into the traps of the digital only when we distance ourselves from the attractions of the analog.

If you do attempt the challenge, send me an email at author@calnewport.com, or leave a comment below, to let me know how it’s going. And, of course, if you complete the challenge and feel fired up about making more permanent changes to your digital life, then I have a book to recommend that you might find useful…

(Photo by Dennis Jarvis.)

December 26, 2019

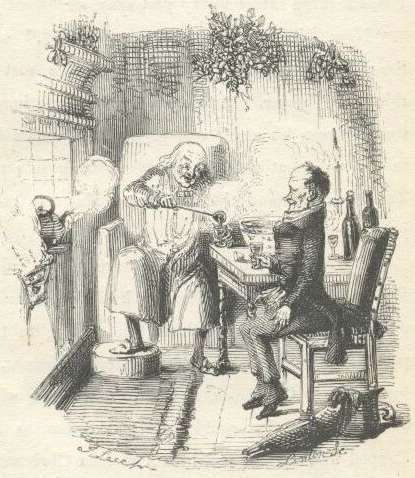

Charles Dickens’s Deep Christmas Strolls

A few days ago, I took my two older boys to a small stage production of A Christmas Carol. Afterwards, me being me, I decided to read up on Charles Dickens and the backstory of his famed novella. In doing so, I came across a neat deep work-themed holiday nugget (the best type of nugget).

According to biographer Claire Tomalin, Dickens crafted much of the tale in his head while engaged in nighttime walks that covered 15 to 20 miles. As a result of this ambulatory cogitation, the entire story took only six weeks to complete in the late fall of 1843.

I like this anecdote: it provides a reminder of what’s possible when you’re able to devote hour after hour of deep thinking on one focused target.

December 13, 2019

Social Media’s Shift Toward Misery

My friend Eric Barker recently pointed my attention to an intriguing paper published earlier this fall in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. It presented a careful meta-analysis of 124 studies looking at the connections between digital media and well-being.

There’s been a lot of academic ink spilled on this subject recently. As I wrote in Digital Minimalism, correlational behavioral studies are exceedingly tricky — you can’t expect slam dunk consistency, but must instead look for general trends in the literature pointing toward some underlying signal in the noise.

Which is all to say, you shouldn’t don’t take any one study too seriously. Even with these caveats, however, I did find this one interesting, as it featured some heavyweight authors, and was clearly written to offer some authority on where the noisy literature seems to be trending at the moment.

The analysis was complicated and contained multiple noteworthy findings, but there was one result in particular I wanted to highlight:

“[D]ifferent [social media service (SNS)] activities have quite different relationships to well-being…Interactions and online entertainment had significant, positive links to well-being. Self-presentation also correlated positively with well-being, but the effect was very small. The largest effect we found in our entire meta-analysis was the negative correlation between well-being and SNS content consumption.”

Here’s what struck me about these observations. Early social media focused on the behaviors that make people feel better: you would post things about yourself and check in/interact with your friends.

Modern social media, which largely displaced the individual feed model with the algorithmically-generated timeline, instead emphasizes passive content consumption, as the amount of times you can check on your friends in a given week is relatively small, while the time you can dedicate to content consumption is boundless.

This seems like a house cards. How much worse can these services make us feel about ourselves before we realize there are other ways to get the things we used to love about the social internet?

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers