Cal Newport's Blog, page 22

March 22, 2020

Carl Jung’s Fantastical Retreat

I open Deep Work with the story of a stone tower that Carl Jung built on the shores of the upper lake of Zurich, near the small town of Bollingen. Jung would retreat to an inner sanctum inside the tower, modeled after meditation rooms he had seen on a tour of British controlled India, to think deeply about his breakthrough work on psychiatry and the collective unconscious.

It always struck me that Jung’s Bollingen Tower, as he called it, seemed almost purposefully fantastical, as if Jung was using its form to induce states of deeper creativity. The other day, while reading Anthony Steven’s insightful guide, Jung: A Very Short Introduction, I learned my instinct was right. As Stevens explains:

“The fantasies and rituals common to childhood assumed a heightened intensity for [Jung], and they influenced the rest of his life. For example, his adult delight in studying alone in a tower he built for himself at Bollingen on the upper lake of Zurich was anticipated by a childhood ritual in which he kept a carved manikin in a pencil box hidden away on a beam in the vicarage attic. From time to time, he visited the manikin and presented him with scrolls written in a secret language to provide him with a library in the fastness of his attic retreat.”

I really enjoy stories of deep thinkers who build elaborate work environments to help extract more creativity and quality from their brain, it’s a classic example of the deep life in action.

For more case studies like Jung’s tower, see these two posts, which look at elaborate work spaces designed by J. K. Rowling, Neal Stephenson, Michael Pollan, David McCollough, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Hans Zimmer, and Gustav Mahler. Also relevant is my post on how virtual reality might bring these same style of brain-boosting environments to a much wider audience.

March 21, 2020

Building a Career that Matters

A reader recently asked me the following question:

“You talk about developing rare and valuable skills specially those which the market values, but at what point do find yourself doing something meaningful? Yes, society would value you and compensate you, but at what costs. I know many people that are highly skilled, but hate their job/life. Is there an equilibrium in which you can develop rare and value skills while still being happy/proud about what you do?”

This question is important. In fact, it’s so important that I dedicated the fourth and final rule of my book So Good They Can’t Ignore You to this topic. Since it’s been nearly eight years since that book came out, I thought it might be useful to provide a brief summary of the answer I provided back then.

I started this rule noting that for many people, having a “unifying mission” to your working life can be a source of great satisfaction. To illustrate this point, I then told the story of Pardis Sabeti, a brilliant biology professor at Harvard who uses advanced algorithms to help find cures to deadly viral diseases.

“As I spent time with Pardis,” I wrote, “I recognized that her happiness comes form the fact that she built her career on a clear and compelling mission — something that not only gives meaning to her work but provides the energy needed to embrace life beyond the lab.” The question I then tackled is how one finds the type of mission that sustains Pardis Sabeti.

My answer spans four chapters, but here’s the main idea: it’s very difficult to identify a truly impactful and satisfying mission until you master useful skills. As I argued, cribbing a term from the systems biologist Stuart Kauffman, the really interesting missions, like Pardis Sabeti using cutting-edge algorithm theory to cure old diseases, are usually found in the adjacent possible — the space just beyond the cutting-edge of the relevant skills.

The conclusion is that if you want to do something truly useful with your professional life, don’t start by figuring out your “mission.” Instead, identify some potentially useful-looking skills, then push yourself to the cutting edge with a single-minded intensity. It’s only then, once you’ve mastered the foundational abilities, that you’ll be able to find that spot in the adjacent possible where the meaningful mission lurks, waiting for its champion.

March 20, 2020

Bill Gates’s Prescient Internet Prediction

I recently stumbled across a 1993 John Seabrook profile of Bill Gates from The New Yorker. It initially caught my attention because of its opening, which provides a nice snapshot of the early days of email. On a whim, Seabrook, who has never met Gates, sends him an email (from a CompuServe account). Eighteen minutes later, Gates replies.

Simpler times.

But I ended up more struck by a passage found deeper in the piece. “Microsoft’s ambition is to supply the standard operating-system software for the information-highway machine,” Seabrook notes. Because this was before broadband consumer internet was even on the radar, Microsoft assumed this machine would depend on the existing cable TV infrastructure, and therefore be sold as box that plugged in like a VCR.

Seabrook traveled to Redmond to see prototype devices demonstrating this vision, and reported the following:

“I heard a lot about ‘intelligent agents,’ which will at first be animated characters that occasionally appear in the corner of your TV screen and inform you, for example, that President Aristide is on ‘Meet the Press,’ because they know you’re interested in Haitian politics, but will eventually be out there on the information highway, filtering the torrent of information roaring along it, picking out books or articles or movies for you, or receiving messages from individuals.”

Microsoft was prophetic in this planning. Today, we do interact with powerful machine learning algorithms that strive to learn more about us from our behavior and use this to deliver us more of what it thinks we want to see from the internet. This modern experience, however, is not delivered through machines connected to our TVs, but instead by social media platforms browsed with our phones.

These small details aside, Bill Gate’s early 1990 vision of how the “internet highway” would evolve was remarkably accurate. Which makes it all the more surprising that Microsoft fell so far behind in the consumer internet sector.

March 19, 2020

On Craft and the Human Condition

In Deep Work, I tell the story of Ric Furrer, a general blacksmith who runs a forge in Door County, Wisconsin: a rural idyll near Lake Michigan’s Sturgeon Bay. He works in a converted barn whose doors he often keeps open to the surrounding farm fields to vent the heat, his hammer blows echoing for miles. He makes a living with architectural metal work, but he’s known for his rare mastery of ancient weapon forging techniques. I came across him in a 2012 Nova episode in which he recreates a viking sword using crucible steel (see above).

In Deep Work, I write the following:

“Ric Furrer is a master craftsman whose work requires him to spend most of his day in a state of depth — even a small slip in concentration can ruin dozens of hours of effort. He’s also who clearly finds great meaning in his profession. This connection between deep work and a good life is familiar and widely accepted when considering the world of craftsmen.”

As I then elaborate, there’s something about mastery that resonates with the human condition. When we observe someone successfully apply a hard-won skill — an athlete, a writer, a leader, an adventurer, a musician — we become rapt, our admiration unmistakable. We also, crucially, tend to feel a moment of inspiration in which we experience a compulsion to pursue something noteworthy ourselves.

I take such intuitions seriously, as they tend to point us toward the things we deeply need. The conclusion here being that the incremental but upward road to mastery — whether it’s in some professional endeavor or hobby — is fundamental. A quick tap on a glowing screen can conveniently banish boredom in the moment. To instead redirect that instinct toward your equivalent of Furrer’s blacksmith hammer, however, can be transcendent.

March 18, 2020

The Astonishing Spread of the Victorian Internet

As someone who studies technology and culture, I’ve noticed that we’re perpetually caught off guard when an unusually useful new innovation spreads rapidly. We tend to quickly claim that this latest fast adoption is unprecedented.

Historically speaking, however, these quick expansions might be more common than you realize. I was recently re-reading one of my favorite history of technology titles, Tom Standage’s The Victorian Internet. In it, Standage summarizes the astonishing rapidity with which the American telegraph network grew.

In 1846, he notes, the only telegraph in the country was the 40-mile experimental line that Samuel Morse strung between Washington, DC and Baltimore in a bid to secure congressional funding. By 1848, there were 2000 miles in the country. By 1850, there were 12,000 miles operated by twenty different companies. By 1852, there were 23,000 miles with another 10,000 under construction — a 600 times increase in six years.

There’s not a sweeping conclusion to draw from this anecdote, beyond the idea that American technophilia is far from new.

March 17, 2020

The Deep Life: Some Notes

Over the past fifteen years, I’ve covered many different topics in my writing that all seem to roughly orbit ideas around productivity, technology, and meaning. Some of my readers have taken to unifying this prescriptive worldview with a simple description: the deep life. Giving its foundational role in what we do here, I thought it might be useful to summarize how I think about this philosophy at the moment.

To me, the deep life is about focusing with energetic intention on things that really matter — in work, at home, and in your soul — and not wasting too much attention on things that don’t.

Those who embrace the deep life often push some of these efforts to a place that seems radical to outsiders, but it’s exactly in this extremeness that they find the deep satisfaction. A life focused intensely on the things that really matter — even if it’s riddled with ups and downs — trumps a comfortable life that unfolds with haphazard numbness or excessive narcissism.

The tricky part in cultivating a deep life, of course, is figuring out what things matter. This will differ between different people. I strive to divide my focused attention among four categories:

community (family, friends, etc.),

craft (work and quality leisure),

constitution (health), and

contemplation (matters of the soul).

In each of these areas I keep striving to identify the big swings — the actions or commitments that will make the most difference — while clearing out the detritus that gets in the way (this latter goal giving rise to my obsession with productivity). They all interact: constitution enables better craft, while contemplation, as it so often does, provides a template for basically everything that’s important. Sometimes I’m more successful in these efforts than others. I’m better at it now than when I was at 25, and think I’ll be even better when I’m 45.

So there it is: a short summary of the underlying philosophy that gives rise to so much that I end up writing about, from the zen valedictorian, to career capital, to deep work, to the importance of digital minimalism. You’re only granted so much energy to expend in a lifetime. You’re almost certainly best off focusing it as intensely as you can on the targets that seem to really move the needle.

March 16, 2020

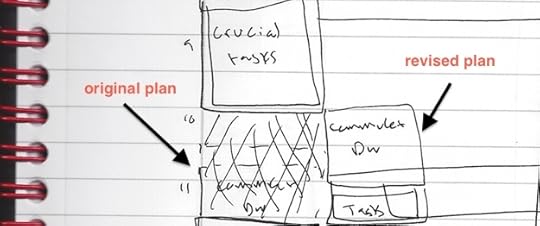

Text File Time Blocking

As longtime readers know, I’m a big advocate of time blocking as a productivity method. Running your day from a to-do list (or, God forbid, an email inbox) leads to sub-optimal returns on the energy invested. The superior method is to give every minute of your workday a job by actually blocking off your time and assigning specific work to the blocks. In my experience, a serious commitment to time blocking can roughly double your results. (For more details, see this article or Rule #4 of Deep Work.)

Anyway, this is all to say that I was excited when several readers pointed me toward a nice variation of time blocking implemented by Jeff Huang, a computer science professor at Brown University.

As detailed in a post he wrote about his method, Huang uses a plain text file to make his time block plan for the day. (Though I use a paper notebook for my time blocks, I too appreciate the versatility of plain text files.)

Here’s an example schedule provided by Huang:

2017-11-31

11:00am meet with Head TAs

– where are things at with inviting portfolio reviewers?

11:30am meet with student Enya (interested in research)

review and release A/B Testing

assignment grading

12pm HCI group meeting

– vote for lab snacks

send reminders for CHI external reviewers

read Sketchy draft Zelda

pick up eye tracker

– have her sign for it

update biosketch for Co-PI

3:15pm join call with Umbrella Corp and industry partnership staff

3:45pm advising meet with Oprah

4pm Rihanna talk (368 CIT)

5pm 1:1 with Beyonce #phdadvisee

6pm faculty interview dinner with Madonna

What makes Huang’s system particularly interesting is that he then annotates his time block schedule with notes about what actually happened during each block:

2017-11-31

11:00am meet with Head TAs

– where are things at with inviting portfolio reviewers? A: got 7/29 replies

– need 3 TAs for Thursday lab

– Redesign assignment handout will be done by Monday, ship Thursday

11:30am meet with student Enya (interested in research)

– they’re a little inexperienced, suggested applying next year

review and release A/B Testing assignment grading

12pm HCI group meeting

– automatically generate thumbnails from zoom behavior on web pages

– #idea subliminal audio that leads you to dream about websites

– Eminem presenting Nov 24

– vote for lab snacks. A: popcorn and seaweed thing

got unofficial notification ARO YIP funding award #annual #cv

read Sketchy paper draft

– needs 1 more revision

– send to Gandalf to look at?

Zelda pick up eye tracker

– have her sign for it

update biosketch for Co-PI

unexpected drop in from Coolio! #alumni

– now a PM working on TravelAdvisor, thinking about applying to grad school

3:15pm join call with Umbrella Corp and industry partnership staff

– they want to hire 20 data science + SWE interns (year 3), 4 alums there as SWE

3:45pm advising meet with Oprah

– enjoyed CS 33

– interning at Facebook

4pm Rihanna talk (368 CIT)

5pm 1:1 with Beyonce #phdadvisee

– stuck on random graph generating crash

– monitor memory/swap/disk?

– ask Mario to help?

– got internship at MSR with Cher

– start May 15 or 22

– will send me study design outline before next meeting

– interviewing Spartacus as potential RA for next semester

6pm faculty interview dinner with Madonna (Gracie’s)

– ask about connection with computer vision

– cool visual+audio unsupervised comparison, thoughtful about missing data, would work with ugrads (?), likes biking, teach compvis + graphics

– vote #HIRE

#note maybe visit Monsters University next spring, Bono does related work

Huang then saves the document, leaving a record of what he did and what he learned during the day.

I love the simplicity of this digital implementation and its use of of post-hoc annotation. It helps emphasize the reality that if you want to get more important things done, you don’t need high tech software or complex systems. The right strategy implemented in a low-friction manner can be more than enough.

March 15, 2020

Mikhail Botvinnik and the Invention of Modern Chess Training

Former world chess champion Mikhail Botvinnik helped build the Soviet’s dominant chess system. His pupils included Anatoly Karpov, Garry Kasparov and Vladimir Kramnik: all world champions as well.

According to Wikipedia, perhaps Botvinnik’s biggest contribution was figuring out the right way to train people to get better at chess:

“Botvinnik’s example and teaching established the modern approach to preparing for competitive chess: regular but moderate physical exercise; analysing very thoroughly a relatively narrow repertoire of openings; annotating one’s own games, those of past great players and those of competitors; publishing one’s annotations so that others can point out any errors; studying strong opponents to discover their strengths and weaknesses; ruthless objectivity about one’s own strengths and weaknesses.”

This quote came to my attention when a reader pointed me toward a tweet about Botvinnik from Washington Post reporter Harry Stevens, who added the following commentary: “seems like a generally smart way to get good at just about anything.”

I agree. More to the point, this got me wondering how many modern endeavors, especially within the rapidly developing knowledge sector, are still waiting for their own Botvinnik to help figure out how to get serious about getting better.

March 14, 2020

On Irrational Numbers and Deep Thinking

Today is March 14th, which to us math nerds is also known as Pi Day, in reference to the first three significant digits of the mathematical constant pi (3.14).

Part of what makes pi interesting is that it’s one of the most famous irrational numbers, meaning that it cannot be expressed as the fraction of two whole values (though 22/7 comes pretty close). In honor of Pi Day, I thought I would learn more about the history of irrational numbers, so I turned to one of my bookshelf favorites, The World of Mathematics: a four-volume history of math, edited by James R. Newman, and published in a handsome faux-leather box set in 1956. (I picked up my copy at a used book sale five years ago.)

The first volume contains an extended essay (originally a short book) titled “The Great Mathematicians,” written by Herbert Western Turnbull, the late Scottish algebraist. Turnbull dedicates much of the essay to great innovations from ancient Greek mathematics. It was Pythagoras (570 – 495 BC), he notes, who is most often credited for discovering that irrational numbers exist.

We know something of the proof that Pythagoras used due to a later account by Aristotle. The proof is elementary by modern standards (indeed, it’s a common example in undergraduate-level discrete mathematics courses). It goes something like this…

Consider a square with sides of length one. Applying the Pythagorean Theorem (which, of course, was brand new in Pythagoras’ time), it follows the length of the diagonal of this square is the square root of 2. It is this common value that was shown to be irrational.

To make this claim, let us assume, for now, that the square root of 2 is a rational number. We can show this will lead to a logical contradiction. This march towards a contradiction unfolds as a rapid-fire sequence of basic number theory and algebraic claims:

If the square root of 2 is rational, then it can be written as x/y, for two whole numbers x and y that share no factors in common, which implies…

that if we square both sides, then 2 = x^2 / y^2, and therefore, x^2 = 2 * y^2, which implies…

x^2 is even (since it is expressed as 2 times another whole number), which tells us that x must also be even, because if you square an odd number you would get an odd number, which implies…

x^2 = (2k)^2 = 4k^2, for some whole number k, which, after doing some algebra, tells us that y^2 = 2k^2, which implies…

that y^2 is even, and therefore y is even (by the same arguement that we applied to x^2).

We have now shown that both x and y are even. But earlier we assumed they had no factors in common. If they are even, they would have a factor in common (namely, 2). This is a contradiction! Math cannot have contradictions, so our original assumption that the square root of 2 is rational must have been wrong.

We might think of this proof as easy, but as Turnbull argues, the result should not be dismissed:

“That will ever rank as a piece of essentially advanced mathematics. As it upset many of the accepted geometrical proofs it came as a ‘veritable logical scandal.'”

The discovery of irrational numbers turned out to be more than just a logical scandal, it also caused theological issues. Pythagoras’s cult had been convinced that everything in the universe could be reduced down to whole numbers. The idea that values existed that could not be expressed with whole numbers alone destabilized this understanding of existence — spawning a number-theoretic crisis of faith.

It’s worth briefly visiting this history of irrational numbers because it’s interesting, and because today we celebrate one such value. But for anyone who shares my interest in cultivating a deep life, this story holds a more compelling layer. It reminds us that there was a time, almost 3000 years ago, when a select group of lucky ancient philosophers could build an entire system of meaning out of simply thinking hard and then marveling at what they discovered.

The mind, when properly cultivated, really does contain multitudes.

March 13, 2020

On Digital Minimalism and Pandemics

One of the more profound representations of the soul in the Western Canon is the Chariot Allegory from Plato’s Phaedrus dialogue:

“[T]he charioteer of the human soul drives a pair, and secondly one of the horses is noble and of noble breed, but the other quite the opposite in breed and character.”

As elaborated by the character of Socrates in the dialogue, the charioteer represents our soul’s reasoned pursuit to cultivate a worthy life. This task requires the charioteer to allow the noble steed, representing our moral intuitions, to lead the way, while preventing its ignoble partner, representing our base instincts, from drawing the soul off course.

In Digital Minimalism, I use this allegory to help understand how to navigate both the promises and perils of modern technology. The minimalist, I argue, deploys technology in specific, intentional ways with the goal of empowering the noble steed. The maximalist, by contrast, deploys technology casually, allowing it to immeasurably boost the strength of the other horse.

I’m bringing this up now because it occurred to me that these ideas have probably never been more relevant than amidst the anxiety caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

In this current situation, for most people, the constant monitoring of online news about the virus is providing pure fuel to the ignoble steed, dragging the allegorical chariot away from what’s good and awe-inspiring about life — even during turmoil — and toward bottom-less anxiety and pseudo-paralysis. The ignoble steed always craves more of this attention-catching information. What if something extra terrible just happened? What if I find a link that makes me feel better? But in this feverish pursuit, the charioteer loses control.

There is, I propose, a simple two-part solution to this state of affairs.

First, check one national and one local new source each morning. Then — and this is the important part — don’t check any other news for the rest of the day. Presumably, time sensitive updates that affect you directly will arrive by email, or phone, or text.

This will be really hard, especially given the way we’ve been trained by social media companies over the past decade to view our phone as a psychological pacifier.

Which brings me to the second part of the solution: distract yourself with value-driven action; lots of action. Serve your community, serve your kids, serve yourself (both body and mind), produce good work. Try to fit in a few moments of forced gratitude, just to keep those particular circuits active.

This doesn’t mean abandon technology. This current moment reveals many ways to deploy tech to strategically boost the noble steed. Our modern tools enable you to video conference more often with friends and family, or to dive into deep topics that have nothing to do with flu viruses, or to coordinate with your community and find out how you can be useful.

This, then, is what digital minimalism has to say about pandemics. You cannot take your technology lightly. You’re the charioteer facing two horses: it’s up to you which one you want to empower.

#####

To help practice what I preach, my plan is to post more often here in the near future, but on topics that have nothing to do with the coronavirus. With this in mind, if you have any questions you’ve always been meaning to ask me about any of the topics I write about — technology, productivity and the deep life — send them to author@calnewport.com, I’ll try to answer some of them in the days ahead.

Cal Newport's Blog

- Cal Newport's profile

- 9945 followers